|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 177:

Opus 177 (January 24, 2006). Another of our periodic Book Sale lists is NOW AVAILABLE here,

including all the books from previous listings that we haven’t been able to

dispose of, plus another 30 or so titles, more of those I somehow keep buying

that duplicate some already on my shelves. One of these days, I’ve got to get

organized. But our chief preoccupation this time is in bidding a heartfelt fond

farewell to New Yorker/Playboy cartoonist Eldon Dedini, with whom

I’ve spent many a convivial lunch over the last several years—a master painter

and hilarity monger without peer. My remembrance of Eldon comes first and is

followed by: NOUS R US —Dark Horse

is 20, Ann Telnaes wins a prize, Pat Oliphant sees nudes, a graphic

novel history of Israel written by Marv

Wolfman, Frank Cho admires Louise Brooks, and we rehearse her story and her

connection with a long-running comic strip character, and that character’s

connection to a famous prize fighter, pausing, slightly, to extol the wonders

of Ron Goulart’s latest book; then

animation’s Oscar candidates and how Steve Jobs may be on the cusp of

revolutionizing the world as we know it; Impressions

and Peeves about the copycat industry of comic books; COMIC STRIP WATCH —a new comic strip takes on our consumer culture;

then we visit an old comic strip by a Native American cartoonist; EDITOONERY —the latest wrinkles in the

never-ending drama of the dying breed; FUNNYBOOK

FAN FARE —reviews of the latest Loveless,

Jack Cross, Superman and Shazam: First Thunder, Boy Wonder, and some first

issues: Sable and Fortune, The

Exterminators, Marlene; Under the

Spreading Punditry, we count the millionaire U.S. senators; BOOK MARQUEE —reviews of Weiner’s 101 Best Graphic Novels and DeForest’s Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio,

winding up with a mild dose of Bushwah. And our usual reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button”

by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned.

WITH FURTHER ADIEU

A

Fond Farewell

Eldon

Dedini, whose painterly cartoons regularly depicted frolicsome forest scenes Gus Arriola, another supreme stylist

whose Gordo comic strip was a

stunning fiesta of design and color, counted Dedini his closest friend in a

friendship of over fifty years that was grounded firmly in their mutual passion

and respect for the visual art they practiced and in a unique Carmel

camaraderie. “Even his signature was a design,” Arriola once said. “—bold,

succinct, an autograph as distinctive as the rich humor it identified. Simply, Dedini —much as one would say Bernini,

Modigliani, Dali—Dedini—all those ending in -I appellations signifying high

art. Few humorists can draw passably, if at all. Eldon was both an accomplished

illustrator and a proven humorist. His pictorial and literary recording of

international events and domestic culture through his award-winning years was

always timely, always cogent and always remarkably funny.”

Quoted in the Monterey Herald’s front-page obituary for Dedini, Lee Lorenz,

cartoon editor at The New Yorker for

many of the years Dedini’s cartoons were published therein, said: “While a

million people can draw, very few can cartoon well. To be a cartoonist you have

to be a stylist, and that’s not easy to come by. It transcends technique. And

he was an excellent idea man. He had a wide-ranging imagination. He was tough

to edit because he didn’t need much editing. I never asked him to redraw, which

at The New Yorker is quite unusual.

If 20th century cartooning is ever looked at seriously,” he

concluded, “Eldon Dedini will be one of the outstanding figures of American

comic art.”

“He could do anything with paint,”

said Playboy’s cartoon editor

Michelle Urry, who knew the cartoonist for over 30 years. “He knew anatomy

brilliantly and he could throw away all those lines. And he was funny, very

funny. I think it was wonderful he came down to earth for us.”

Recognized four times by the

National Cartoonists Society as the year’s best magazine cartoonist (1958,

1961, 1964 and 1989), Dedini was a master of his medium. He was influenced by

the radiant color of E. Sims Campbell, who specialized in those harem cartoons

at Esquire. The severe simplification

and commanding bold line of a Dedini drawing came, he said, from studying Peter

Arno’s cartoons and Whitney Darrow, Jr.’s in the venerable pages of The New Yorker. But in the last

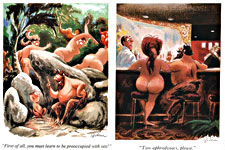

analysis, his artistry was uniquely his own. He abstracted human anatomy,

redesigning and simplifying it to suit the pose and the picture. And then he

cast the cartoon, creating the characters for their roles. All his men have

bulbous noses and pop-eyes, but each is an individual caricatural design: the

noses are not all the same size and shape—they curve and hook, and bend and

bulge differently, from face to face. And the women, if they’re old, are

usually lumpy and frumpy, with noses to match the men’s. The young women,

however, are erotic exaggerations, bosoms and buttocks galore, legs that go on

forever, and perfectly oval porcelain faces, mostly heavily lashed eyes and

smiles all tooth.

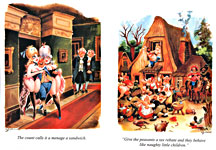

Dedini loved drawing crowd scenes

and elaborate costumes and architectural detail: after simplifying the elements

of a composition, he decorated it with visual complexities—patterns of lines

and shapes and colors, varied textures, clothing that draped and swirled,

building interiors with lofty vaulting ceilings and arched aisles and exteriors

with antique sculpted knots and furbelows. Here’s a medieval castle, looming in

its crenelation, being stormed by an unruly army, described by the king on the

parapet as “two hundred thousand peasants from permissive homes.” Dedini’s

sense of humor was as antic as his pictures: typically, it quirked, yoking a

commonplace utterance to a fantastically unlikely speaker in a place neither

belonged, creating a new and always hilarious scrap of existence, and shedding

thereby a liberating laughter and light on the human predicament. A vintage

full-rigged sixteenth century sailing vessel, perhaps a Flemish man-of-war or

Danish pinnace, its majestic stern toward us, with a fair wind and a following

sea, flying the Jolly Roger, its captain on the quarterdeck, saying

expansively, “I love the Caribbean in

February.” Thus, our incongruities make us human and unite us all in a common

weal. But the cartoonist Dedini was more than a cartoonist; or, rather, the

more that he was made him a great cartoonist.

After Dedini’s death, Arriola wrote

to me: “I still can’t believe our beloved friend Eldon Dedini is gone. And as

someone says, I don’t have to believe it if I don’t want to. When I was

introduced to Eldon in 1953, I sensed I was meeting someone of heartening

substance. The following five-plus decades of neighborly activities in Carmel and

Monterey more than proved that sense. Calling Eldon a cartoonist just christens

the tip of an impressive iceberg. Beneath the surface is a superb painter, a

remarkably inventive illustrator, philosopher, and humorist—a keen observer,

revealing life’s little truths with his unerring brush. His chief reward was

the viewer’s invariable burst of laughter. He was a walking repository of

eclectic knowledge about art, history, jazz, wine—you name it. I gave up using

my encyclopedia on a subject search: it was faster to pick up the phone and

call Eldon. Too many of today’s comics stand up and then sit down, seemingly

motivated by anger. Anger is not funny. Eldon was motivated by love, love of

the visual arts, music, sports, literature, and nature—all revealed in his

painterly treatment of man’s ridiculous foibles. Those of us lucky to receive

his personally designed birthday cards, year after year, noted they were always

signed con amore. He was a man as

giving of his time and his talent, aiding friends and organizations in need, as

he was to his craft. He graced every social gathering with his delightful,

informative sought-after company. Among his peers, he was hailed as King not

because he hailed from King City but for his unique multi-talented persona and

courtly demeanor. Famed names of Salinas Valley should in future read

Steinbeck, Ricketts, Jeffers, and Dedini”—referring to the vicinity’s

celebrated novelist, biologist, poet, and, now, cartoonist.

Although he sold cartoons to the

nation’s most sophisticated magazines, all headquartered in Chicago or New

York, Dedini lived all his life in California, most of it within a few miles of

King City, where he was born Eldon Lawrence Dedini on July 29, 1921. “The

Dedini family,” he once wrote, “were originally butter and cheese makers.

Immigrants in 1873 from Lavertezzo, Canton Ticino, Switzerland, on the Italian

border. They made butter and cheese in Corral de Tierra for thirty years,

leasing from David Jacks, the land baron. Then the family moved to King City in

south Monterey County where I was born and escaped the butter and cheese

business. It was with the blessings of my father and mother, who said, ‘Go! The

ranch will always be here if it doesn’t work out.’ I had been copying the funny

papers since I was five years old, and by the age of thirteen, I’d discovered

cartooning was a profession and decided to be a cartoonist.”

Dedini grew up in the Salinas

Valley, “playing accordion at Italian-Swiss weddings and Mexican fiestas,” he

said. Very early, his art education began: “I copied the comic strip

characters—Barney Google, Popeye—all of those, but I always liked magazine

cartoons. And when Esquire came out,

those colored drawings really impressed me. I didn’t exactly copy them—I made

my own. Barbara Shermund, Syd Hoff, Abner Dean—you can copy them, but you

become them, you sink into them. And everybody said, Be original. So I did my

own.”

After high school, Dedini enrolled

at Salinas Junior College—now Hartnell College—whiling away the long daily bus

ride with a deck of cards that he brought along to play Pedro in the back of

the bus with friends. He took art courses at SJC but majored in general studies

so he’d have something to fall back on if cartooning didn’t work out. Thanks to

his art teacher—Leon Amyx—Dedini never needed to fall back. Amyx, an

accomplished watercolorist, had aspired in his youth to be a cartoonist, and he

suggested that Dedini plug the cartooning hole in the art curriculum by

volunteering at the local newspaper.

Interviewed by Lisa Crawford Watson

at the Monterey Herald, Dedini

explained: “I went to the Salinas Morning

Post and the Salinas Index Journal—now

the Salinas Californian—and made an

appointment with publisher Paul Caswell and editor Nelson Valjean to offer my

cartoon services free in exchange for the experience. And it worked. They’d

tell me the news, and I’d illustrate the point in a cartoon. My first was about

the train depot in Salinas and how it was falling apart.” He paused before

concluding the account with just a nudge of a punchline: “You’ve gotta start

somewhere,” he said with a characteristic grin.

At eighteen, still a student at SJC,

Dedini sold his first cartoon to Esquire magazine. When he graduated, he took advice again from Amyx and went to Los

Angeles and enrolled at the Chouinard Institute of Art, where many of the

animators at Disney were training. At Chouinard, he met the woman he would

marry, Virginia Conroy, a painter and etcher. “We were both on scholarships,”

Dedini said. “I was a janitor, and Virginia was a librarian. We got married the

year we graduated, 1944, July 15. I went to work for Universal Studios. Three

months later, all the studios except Disney went on strike, so I went over to

Disney.”

Dedini honed his comedic talents

doing storyboards. “I worked with writers. What they wrote, I put in a

storyboard—a giant comic strip, which was perfect. It was a wonderful

education. You draw maybe a hundred drawings a day—staging, laying it out. All

day long. And if they rewrite the story, you re-draw the storyboards. You learn

never to throw the drawings away because a week later, they say, You know—what

we had last week was better. So I always kept the drawings in a drawer that I

could go back to. I had another drawer in my desk that Disney didn’t know

about—full of drawings I was trying to sell to Esquire. I also sold to all the little magazines—Click, Pic, Nifty, Judge—five or ten

dollars a drawing, and I thought I was in heaven. But I liked the full pages,

not the small cartoons in Collier’s and Saturday Evening Post. I did some

of them, but my heart wasn’t in it.”

He also joined a southern California

watercolor group and learned about painting in color. At Disney during the day,

he worked on such epics as “Mickey and the Beanstalk,” “Ichabod and Mr. Toad,”

and “Fun and Fancy Free.” Nights and weekends at home, he drew cartoons and

sold them through the mail. “When the nights began running into days,” as

Watson put it, “he knew it was time to commit to magazine cartooning.” In 1946

, he was helped to a decision by Esquire’s publisher, Dave Smart, who phoned the cartoonist and offered to double his

Disney salary if he would work exclusively for the magazine, generating ideas

for the other cartoonists as well as being featured himself. Dedini took the

job, knowing that the gags are the most important part of cartooning.

“The gag is the whole secret of

cartooning,” he told Watson. “Style alone will never sell a bum joke. So you

can draw. A million people can draw. The question is, are you funny?”

Dedini was funny for Esquire for the next four years. He sent

in 100 ideas every month, tailoring them for the proclivities of specific

cartoonists—hillbillies for Paul Webb; working class men in their undershirts

at home for Syd Hoff; the frilly-witted young things, Barbara Shermund; the

heavy-set set, Dorothy McKay. Any ideas that weren’t farmed out to the Esquire stable came back to Dedini to

draw.

In 1950, he gave up the Esquire gig, taking Smart’s advice when

the publisher told him that he was ready for The New Yorker. Dedini was back in Monterey County by then, and he

was soon one of The New Yorker’s contract cartoonists: he showed all of his

cartoons first to The New Yorker; any

that the magazine didn’t buy, he could offer elsewhere, and in return, The New Yorker provided some employee

benefits like health insurance. He continued selling also to Esquire. Then came Playboy.

Playboy’s first issue was published at the end of 1953, famously undated so it would stay

on the stands until it sold out. Publisher Hugh Hefner, a frustrated cartoonist

himself, aspired to muster a troupe of distinctive talent to work exclusively

at his new magazine, and he had his eye on Dedini almost from the start. Dedini

remembered: “In 1954, Hefner started writing me to say he wanted me at Playboy. But Esquire had put me on the map, and I felt a certain loyalty. Hefner

wrote four or five years in a row and kept upping the price. By that time, Esquire had been sold, so that did it.”

Just about then, Dedini heard from another cartoonist who had just sold a

cartoon to Playboy and had been

advised by Hefner to apply color “in the Dedini style.” Said Dedini: “I figured

that if they were going to teach people to work in my style, I’d better get in

on some of it.” Most issues of the magazine subsequently featured at least one

full page color Dedini cartoon, and Dedini was soon a contract cartoonist with Playboy as well as with The New Yorker, the seeming conflict

resolved by the simple fact that cartoons for the former wouldn’t be

appropriate for the latter.

In his Dedini obit for the New York Times, Douglas Martin wrote: “Dedini’s Playboy cartoons helped establish the magazine’s image in the

1960s, from take-offs on classic Japanese erotica to urban hipsters. His

sexually brash satyrs in joyful pursuit of astoundingly proportioned, equally

lusty nymphs became as much a Playboy trademark as lascivious advice columns”—and as familiar to readers as the

centerfold pin-ups, he might have added.

“My first cartoon appeared there in 1959,” Dedini told Watson in October

2005, “and I’ve been with them ever since. I guess, since I still feel funny,

I’ll just keep going.” He paused. “Until I don’t.”

Dedini loved the sophisticated wit

of Esquire, and he loved the

opportunity to work in color that Hefner’s magazine afforded him, but for him, Playboy’s focus was a trifle narrow. All the cartoons seemed to be focused on boys

chasing after girls—and catching them, to the randy delight of both, which was

not exactly Dedini’s cup of tea. He reveled in life, his son Giulio told me:

“He appreciated food, wine, people, humor, history, travel, family, sex,

beautiful women, and the outdoors.” He gleefully manufactured ribald comedy in

his Playboy cartoons, but, according

to his brother-in-law, Charles Carey, he was very conservative in his own

relationships. Moreover, to Dedini, the usual Playboy cartoons were boring in the tautology of their constantly

beatific carnality.

During his presentation at the

Festival of Cartoon Art at Ohio State University in 2001, Dedini showed slides

of his cartoons for both The New Yorker and Playboy. One of the latter

depicted an orgy, a writhing pile of naked bodies—what Dedini called “the

standard cartoon” for Playboy. “I try

not to do these too often,” he said. He tried to vary the standard, he

continued, to reduce the monotony of the routine tableau of boys chasing girls

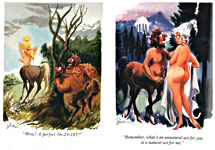

all the time. “I discovered I could go to mythology and use satyrs and so

forth, and it opened up more ideas. The captions could voice very contemporary

ideas but if you put them back there in those mythological times, the result is

an extra dimension of humor.” He showed a slide of a leering centaur saying to

his amply-rounded playmate, “Remember, what’s an unnatural act for you is a

natural act for me.”

“I love to draw,” Dedini said. “I

often start with a scene and no idea. I just draw a mythological scene, and

then leave the drawing lying around, looking at it every once in a while,

keeping it in mind, and maybe I come across a line in a newspaper article that

fits, and I have a cartoon.”

Continuing his search for ways to

escape the standard Playboy cartoon,

he came across Japanese erotic prints. “Well, no,” he corrected himself.

“They’re not erotic. The ones I make are erotic. I sometimes copy Japanese

caligraphy into the cartoon, but I always change something a little in case it

means something I don’t want to say,” he said with a sly grin.

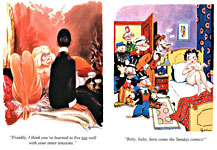

He resorted to history often,

mimicking in caricature a well-known painting—for instance, the famous scene of

the signing of the Declaration of Independence, wherein a Dedini patriot, his

quill pen poised, says, “Frankly, some of those truths don’t seem self-evident

to me.”

Bruegel is a favorite of his. On one

occasion, he imitated a Bruegel painting, cramming people into a typical multitudinous

throng except that most of these Dedini Bruegelians were engaged in revelry of

a more licentious sort than the Dutchman usually contemplated. In Dedini’s

version, one lone man stood in the midst of the orgy, raising his glass and

saying, “Say—this is a nice light beer.”

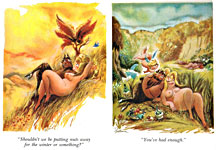

Two cavemen in animal skins watch an

extremely statuesque young woman strut by in naked splendor, and one of the men

says, “The things you see when you haven’t got a club.” While looking at this

cartoon, Dedini commented that he tried to get some socially redeeming stuff

into his Playboy cartoons. Maybe, he

wondered, this was feminist?

About a cartoon that didn’t get a

laugh from his audience, he said:. “Maybe it’s not so funny. But it’s got girls

in it. If you draw the scene with girls in it, Hefner and Michelle most of the

time go for it.”

Dedini didn’t meet Hefner until he’d

worked for the magazine for over twenty years. “I got letters, all the time,”

he said, “but I never met him. And I said to Michelle one time, I’d like to

meet him. And she said, You wouldn’t like him. And she’s his cartoon editor!”

he marveled. “But I have met him, and I liked him,” he beamed, “—of course, our

life styles are entirely different.”

Dedini was a disciplined worker. He

drew every day, starting at about 5 a.m., and every three weeks, he sent 25

cartoon roughs to Playboy and 25

different ones to The New Yorker. He

estimated that he’d published about 1,200 cartoons in Playboy and over 600 in The

New Yorker.

“I’ve had good years and bad years

at The New Yorker,” he said. “Once I

went for a whole year without selling one there. I thought I was just out of

business with them. I couldn’t make ’em laugh there. And then, all of a

sudden—I sold one, two, a half dozen. What they take and what they don’t take

is still a mystery to me after 50 years.”

In concocting New Yorker cartoons, he used much the same tactics as he used with Playboy cartoons but without the amorous emphasis and torrid color. He made historical allusions and sometimes imitated famous paintings. Once he invoked Chagall. “He always has people flying around in his paintings,” Dedini said. What could they be doing up there? And why? So he drew a nightscape with a Chagallian man and a woman in horizontal flying position over the rooftops below, the man saying, “I don’t love you any more, Lucille, and I’m dropping you off at your mother’s house.”

During the Cold War, he loved doing New Yorker cartoons with Marx and Lenin

in them. “I loved to draw them,” he said. “They were the clowns to me.”

“I like the subtle ones,” he said,

showing a cartoon depicting a beach with people seated on the sand, sunning

themselves, the waves breaking in the distance. In the foreground, a father is

answering his son’s question: “Generations of our people have sat by the sea,

my son, and when you are older and have sat by the sea, you will understand.”

Said Dedini: “It might be funny,

eh?”

And here’s Toulouse Lautrec,

standing in all his three-foot-high majesty before a mirror in a hat shop where

he’s trying on a towering top hat. The clerk says, “The derby is better: that

makes you look like Abraham Lincoln.”

In addition to the cartoons by which

he earns his living, Dedini contributed artwork to numerous local Monterey

enterprises and did posters for various civic events, including the annual

Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, a celebrated antique car show.

On November 4, 2005, as we reported

in Opus 173, a show of his work opened in Salinas at the Sasoontsi

Gallery. Entitled “Broccoli and Babes,” it ran until January 3, 2006. Dedini’s

work belongs in museums: it satisfies museum-goer expectations in ways that

much comics artwork on display in museums does not. In the first place, single

panel cartoons can be experienced in a gallery in exactly the way that

paintings and etchings are: the viewer strolls down the gallery, casually

looking at the pictures on the wall, occasionally stopping to read the captions

just as he or she might stop to read the information placards affixed to the

wall next to a Rembrandt or Watteau. And expectations about comics are also

handily satisfied: Dedini’s cartoons make you laugh. So the desires of both art

lovers and comics lovers are gratified, you might say. But there’s more here,

even greater benefits to be savored. You don’t laugh unless you read the

caption and grasp its relationship to the picture it accompanies. Your laughter

thus signals your appreciation of the verbal and visual blending of the

cartoonist’s art. So a third objective, one closer to my own aesthetic heart,

is realized in an exhibition of single panel cartoons.

What’s more, with Dedini’s cartoons

we can take yet another step in appreciation, this time, back to the art lover

who enters a gallery to enjoy the pure unadulterated visual artistry on

display. Dedini’s cartoons are not just funny; they’re not just adroit blends

of words and pictures to comedic ends. They are also works of visual art.

Dedini’s pictures can be enjoyed in much the same way we enjoy Lautrec or

Monet—as feasts for the eye and heart. Even more: it’s clear that many of

Dedini’s cartoons were inspired by his enjoyment of a picture or objet d’art

that he saw somewhere, something that he wanted to, not copy, slavishly, but

emulate, joyfully, in the manner of homage. We see this in his cartoons

rendered in the style of Japanese prints and in the mocking evocation of famous

paintings and artistic styles. Looking at the lush richness of Dedini’s

watercolors, we can often find objects in them depicted so lovingly that we

know they represent the well from which Dedini drew the refreshment of the

picture he made.

Oh, the broccoli? The babes are from Playboy, of course, but Dedini has

done a lot of humorous advertising paintings for Mann Packing in Salinas since

1985, when the president of the company persuaded the cartoonist to create

provocative pictures promoting the product of the world’s largest shipper of

fresh broccoli. (More Dedini babes will be readily available next fall, when

Fantagraphics brings out a collection of Dedini’s Playboy work, assembled under the watchful eye of Michelle Urry,

the magazine’s legendary cartoon editor. A few hints can be eyeballed at www.fantagraphics.com/blog/ ) The Salinas exhibit included cartoon

originals spanning his entire career, even some of the cartoons he did for the

Salinas newspapers. “It really does come full circle,” he said, “from my start

in Salinas to my return to Salinas.”

In returning to the scenes of his

youth in 1950, Dedini joined a colony of cartoonists who made their homes on

the Monterey Peninsula. Virgil Partch, the famed “VIP,” lived nearby in Carmel

Valley, as did Bob Barnes, both magazine cartoonists. Hank Ketcham of Dennis the Menace fame was established

in Monterey, and editorial cartoonist Vaughn Shoemaker, on the cusp of

retirement, lived in Carmel and mailed his cartoons to Chicago. And Jimmy Hatlo

produced his syndicated panel cartoon They’ll

Do It Every Time from a place called Tally Ho in downtown Carmel. Gus

Arriola soon joined the colony. Dedini met Arriola when they served with

Ketcham and Hatlo as judges of a beauty pageant during the Monterey County Fair

soon after Dedini moved to town.

In their judicial roles, the

cartoonists were driven in the parade down Alvarado Street in brand new, shiny

convertibles with the tops down. Their names and pictures of the characters

they drew were plastered on the sides of the cars. “Our wives were there,”

Dedini remembered when we talked, “sitting in the cars. Some beautiful girl was

driving. None of us were used to any of that. There were actually people lining

the street.”

The contest took place in the State

Theater. The girls went strutting by in their swim suits, and the judges (and

their wives) looked at them, and then one of them was declared the winner.

“We were all there, huddled in the

first row of seats in the theater,” Dedini said. “I even have a photograph of

that, our wives and ourselves, looking very young, looking up at the stage.

We’re all smiling and laughing. The judges look a little serious, but not too

serious. It was great fun. I remember Jimmy Hatlo especially—a great bon

vivant, great drinker. Very happy.” He paused. “None of us can remember the

name of the girl who won.”

It may have been the beauty

contestants that supplied the crucial bonding catalyst, although it is just as

likely that Dedini and Arriola, both gifted stylists at their craft, shared a

passion for art. And a love of fellowship that would flourish at Doc’s Lab.

They became fast friends for life.

The playful sense of humor on

display in Dedini’s New Yorker and Playboy cartoons serves as a convivial

introduction to the man, but knowing him requires that we also know about Doc’s

Lab. Doc’s Lab achieved its first blush of fame in the pages of John

Steinbeck’s 1945 novel, Cannery Row, which was about life at the tattered edges of the sardine fishing industry in

Monterey in the 1930s. Doc was a character in the book, but he was more than a

friendly fiction. The real Doc was Edward F. Ricketts, who moved to Monterey in

about 1923 and set up the Pacific Biological Laboratory at 800 Ocean View

Avenue. He operated the Lab there until he was killed in his car at a railroad

crossing in May 1948. Ricketts made a living furnishing live marine specimens

to high schools, universities, and medical research facilities. His occupation

permitted him to do the things he loved most—comb the beaches and inland

waterways of California for exotic creatures and pursue his own researches on

marine life and the evolutionary process, about which he wrote numerous

scientific papers. His research led him inexorably to the conclusion that all

living things were part of an organic whole, the parts of which cannot be

understood in separation from one another. Ricketts was, in short, one of the

first ecologists.

From the outside, the weathered clapboard building on Cannery Row looks more like a garage with a room on top than anything someone might mistake for a laboratory. Doc’s lab equipment was located in the basement—the garage part; he lived in the four upper rooms. The place stood vacant after Doc’s death until 1951, when Harlan Watkins took up residence there, renting it from Yock Yee, the owner of Wing Chong Market across the street who had acquired the Lab from Steinbeck. Watkins had come to Monterey in 1946 to teach English at the high school. He was a bachelor and so he had plenty of spare time to soak up information on a vast array of topics. And he was passionate about jazz—the Dorseys, Ellington, Basie, Goodman, Shaw, James. Soon after Watkins moved in, he started inviting people over for drinks and conversation and jazz late on Wednesday afternoons. Some of the people were friends and colleagues. Some were not. Said Dedini: “The best thing that ever happened to me happened the evening Harlan telephoned and said, ‘Report to Doc’s Lab—you have friends here.’ I went. Until that moment, I’d never met him.”

The remark captures the essential

Dedini like no other: he was open to life, unquestioning in his acceptance of

it in its various manifestations.

Watkins created a Wednesday ensemble

of local personages—doctors, lawyers, architects, teachers, a sculptor, even a

judge, and, with the addition Dedini, Arriola, and Ketcham, cartoonists. On any

given Wednesday, a crowd of men eddied through the second-floor rooms, filling

the air with smoke and talk and laughter while a record player tried to make

itself heard. Arriola recalled his first visit there: “We were awash with the

bonhomie explicit in those rooms. The repartee so glib, so sharp, it sounded

scripted. There was Harlan, stentorianly holding forth behind the bar with his

good friend and fellow teacher, Ed Larsh, the two seemingly conducting a seminar

on everything. Politics, sports, jazz, literature, education, martini jokes—you

name it. And all with a scholarly control that welded your attention to the

point so well you could have passed a written exam afterward. Skirting

pedantry, the operative phrase was always—enlightening fun. It was a club that

didn’t like to be called a club. It was a men’s club for men who didn’t like

clubs. It was just a group of—what’ll I call them?—just guys that enjoyed being

together.”

Watkins gave up the place in about 1955

when he got married. And the Wednesday group was thrown into a state of panic.

“There were about eight or nine of

us,” Dedini told me, “and we said, Where are we going to go every Wednesday

night if we lose this place? So Harlan told us that he was paying $40 a month

rent, and the Chinese landlord across the street had often told him that for

$60 a month, he could buy the place. I’m a little hazy: Harlan may have started

proceedings to buy it, but we took over his option. We incorporated under the name

Pacific Biological Laboratory in 1956.”

And the Wednesday evening gatherings

continued unabated.

At first, the PBL numbered less than

a dozen, but it eventually reached nineteen or twenty. A typical evening at the

Lab commenced after work on Wednesdays. Members, still mustered by Watkins,

would begin collecting at five o’clock or five-thirty in the back room at the

bar. After a drink or two and some conversation about their days’ adventures,

they’d begin to play jazz records. Watkins might well launch into a lengthy

disquisition uncovering some obscure bit of vintage jazz lore, but his lectures

were not confined solely to jazz. He was widely read, and what he hadn’t read

about, he could fake. He could fake such things because he was forever curious

about whatever hove into view. Dedini remembered taking a short trip with

Watkins:

“Every trip with Harlan took a long

time. Getting gas for the car, he’d have a long conversation with the station

attendant about the three choices of gasoline at the pump—pros, cons,

politics—until I went nuts. Then we had to stop at Castroville at a drug store

to get a chapstick or something, and he’d engage the salesgirl in some

unbelievable conversation, asking about her life, the store, Castroville, if

she knew this book, that movie, and so on. Sometimes late at night, I realize a

lot of my humor was honed by this intellectual lunatic. Harlan was a straight

man. A satirist with a straight face, a ricochet man who fit in everywhere and

nowhere. What can you say about a guy who was capricious, imperial, funny,

shrewd, mercurial, ever ready, lordly, principled, windy, nocturnal,

competitive, gallant, hilarious, a bull-shitter and smart, smart, smart.”

As the afternoon faded into evening,

the Wednesday denizens of Doc’s Lab listened less to the records and talked

more. Sitting around that tiny room, they talked about politics and civil

rights and books and their various professional triumphs and complaints. The

variety of occupations and interests in the room widened perspective. “I

learned about medicine and the law,” Dedini said, “and they learned about

cartooning. And we all learned about literature from Harlan.”

Gradually, the music was background

music. “Every now and then,” Arriola remembered, “Harlan would get up and stamp

his foot and say, Listen to that—listen to that!”

About eight or eight-thirty, the

group would rise and go together to dinner at a restaurant down the street.

“There were one or two restaurants,” Dedini said. “More like joints. Neil de

Vaughn’s wasn’t bad.” The group ate at de Vaughn’s and continued their

conversations. For several hours, Dedini remembered.

Members often brought guests to the

Lab. After a three-day workshop on “creativity” at the University of California

at Berkeley, Arriola showed up with Max Shulman and Dedini with Art Buchwald.

Not all the guests were famous. One time, Watkins invited a Cannery Row habitue

named Grant Mclean, nicknamed Gabe. Gabe was Steinbeck’s model for Mack in the

novel. At de Vaughn’s, Watkins seated Gabe next to Dedini, who was a sort of

factotum (secretary-treasurer) of PBL and therefore sat at the head of the

table. Later, Dedini reported that during dinner, Gabe (or Mack) wet his pants

and some of the byproduct found its way into Dedini’s shoe. Being an officer has

its drawbacks.

After the ritual dinner at de

Vaughn’s, the group always returned to the Lab for an after-dinner drink. And

more jazz. “We’d play jazz,” Dedini said, “I would say until midnight, one

o’clock—sometimes two or three in the morning. Not everybody. The doctors would

say, I’ve got an operation in the morning; I’d better go. Sometimes

cartoonists, who don’t know what they’re doing, stayed later. But we had

deadlines, too. Many a time, one of the doctors would get a call and say, I

gotta go deliver a baby. He’d say, I may be back; I may not. And if everything

went well, he’d come back. The music, the jazz, was the key thing. We would

bring our own records that we liked from home, and play them for the others.

And we’d discuss the music. We became authorities. At least on cool jazz, West

Coast jazz, bop—music was changing in those days. The Monterey Jazz Festival

started in the 1950s,” he continued. “And a good many of the Lab members were

on the Board of the Monterey Jazz Festival when it started.”

The Monterey Jazz Festival was born

in the imaginations of disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and newspaperman Ralph Gleason

of the San Francisco Chronicle, who,

at the time, was conducting the only newspaper column devoted exclusively to

jazz. They dreamed of an outdoor jazz festival. And they started talking about

Monterey as the site for it after having visited and imbibed both drink and

jazz lore at Doc’s Lab. “The Jazz Festival was born right here at this bar,”

Arriola told me. The first Festival opened on October 3, 1958, and among the

performers were Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and Billie Holiday, just nine

months before she died.

During an intermission at one year’s

Festival, Dedini and some other PBL members went up on stage to have their

photograph taken. Duke Ellington was still on stage, seated at the piano,

putting eye drops in his eyes. When Dedini was introduced as “a cartoonist who

sometimes draws jazz cartoons,” Ellington got up and, without saying a word,

pulled out his wallet and started looking through it as he meandered,

aimlessly, around the platform. Finally, he found what he was looking for, Dedini cartoons turned up

everywhere. On a trek to the wineries in Napa Valley, the PBL crew visited

Martini’s old winery, and they noticed one of Dedini’s cartoons neatly tacked

to a door. When they introduced the cartoonist, their escort declared, “Don’t

leave” and went to get his boss, Louis Martini. After Dedini autographed the

cartoon, the old man invited all five of the group into his home for a

spaghetti lunch.

During the Kennedy years, Dedini

drew a cartoon in which a couple of tourists in Egypt are contemplating the

Sphinx, which looks remarkably like the First Lady. One of the tourists says,

“I don’t know. Lately, everything looks like Jackie Kennedy to me.” Soon after

the cartoon was published, Dedini got a note on White House stationery,

requesting the original. He complied. After Jackie’s death, Dedini’s cartoon

was among her personal items that were sold at a celebrated auction.

When the Jazz Festival was in

session, some of the musicians would come by Doc’s Lab after their performances

and jam into the wee hours.

“We’d have a few drinks and talk

about starting our own Cannery Row Jazz label,” Dedini said. “And Gus and I

would sit in the party room at the Lab, drawing up logo designs and record

jackets.”

The walls of the second floor rooms

were eventually plastered with colorful souvenirs of these efforts—these and

others. Posters and other artifacts designed by Arriola or Dedini for community

events often became a permanent part of the decor, remaining on the wall long

after the events they were intended to advertise.

The organization of PBL was

ferociously informal. In writing about Doc’s Lab years later, Ed Larsh took

pride in the realization that no one in the group ever thought of it as a club.

Yet the corporation that owned the place had a membership: these were the

people who paid dues sufficient over thirty-five years to buy the Lab. Men became

members by unanimous acceptance; but there was never a vote. They decided to

restrict their number to about twenty, but they accepted many “permanent

guests” who were not members but were always welcome.

The group held numerous parties at

the Lab on days or nights other than Wednesdays. Many of these affairs were in

honor of their wives (or, perhaps, to pacify them for putting up with their

husbands’ coming home in the wee hours every Wednesday). The group also had its

own wine label, and various of its members made periodic trips to Hecker Pass,

where they bought cases of gallons of wine or, even, barrels of it. Then in the

basement of the Lab, they’d bottle the wine and affix their label, using

second-hand bottles from de Vaughn’s.

Doc’s Lab was more than a place. It

was a feeling, an ambiance. “We were just going there to listen to music and

have a beer or two,” Larsh wrote. “But we discovered that the place has a kind

of magic about it.” For Larsh, the spell was cast by the shade of Ed Ricketts, charismatic

advocate for ecology and non-teleological thinking. For Ricketts, everything

was connected: it was all part of a communal wholeness, a glorious web of being

in which all living as well as inanimate things had a place and function and

depended upon one another in a grand harmonious scheme. In Doc’s Lab under the

aegis of Harlan Watkins, the additional conjuring was done by the music and the

drinks and the fellowship. Sitting together silently listening to jazz, the men

were enveloped by an oceanic feeling; all other concerns evaporated in the

sound, and a transcendent sensation of at-one-ness in some sort of separate

universe bonded the group. A sense of community and fellowship prevailed and

remained with them even after the sound of the music faded.

By the time I met Dedini and

Arriola, the PBL no longer convened regularly. Concerned about the historic

associations of the place, the members were eager to assure its preservation,

and to that purpose, they sold it to the city of Monterey several years ago.

“It’s still our club,” Arriola told me. “The city owns it, but we have the use

of it until the last one of us goes. We’re all aging. We kid about it being a

last man club.”

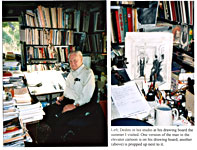

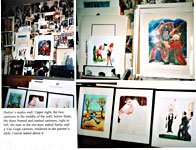

I visited Dedini in his hillside

home and studio in the summer of 2004, during one of my annual pilgrimages to

Carmel. One wall of his livingroom is windows that open onto a deck. From the

deck, we could see, through some encroaching trees, Carmel Valley in the

distance. Around the livingroom and the adjoining studio were stacks of

magazines—“For research,” Dedini explained. And bookshelves in his studio were

laden with books. One wall was a bulletinboard on which were tacked photographs

of friends (one of Dedini with Ketcham and Arriola) and famous personages

(Louis Armstrong, Jean Belmondo, Phil Silvers), postcards, sketches, and

numerous of his own cartoons, sometimes clippings, sometimes originals, matted

for display but often overlapping each other and other fragments pinned to the

wall. Scattered among the pictorial matter were various bits of paper, each

neatly lettered with slogans or sayings: “Ideas cannot be owned; they belong to

whoever understands them. Dying is easy; comedy is hard. Never go to a young

doctor or an old barber. The more opinions you have, the less you see.” On a

shelf beneath this array were some record albums, a half-dozen unopened bottles

of wine, and a radio. Leaning up against the cabinet under the shelf were

several of his color cartoon originals, matted and framed—and, in several

instances, unfinished.

Dedini explained that he almost

never finishes a cartoon at a single sitting. After experimenting with various

compositions, he selects the one that pleases him and sketches it with charcoal

outlines onto watercolor paper. Then he begins to paint. He paints until he

gets to a place where he hasn’t decided what color, say, or texture to deploy.

Then he stops. He puts the unfinished art in a matted frame and lets it

marinate for a while, sometimes for days, while he does other things.

Sometimes, he said, he takes the framed unfinished cartoon into the bedroom at

night and stares at it as he falls asleep. “I keep looking at it out of the

corner of my eye,” he said. “I let it tell me, slowly, what it needs.” And when

it gets through telling him, he finishes it.

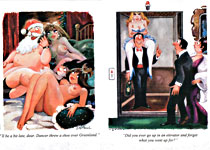

Two of the unfinished cartoons I saw were intended for the Christmas holiday issues of Playboy. One showed a plump, naked Santa gamboling in bed with three naked women in glorious embonpoint. Santa is talking into his cell phone: “I’ll be a bit late, dear. Dancer threw a shoe over Greenland.” The women are all grinning. Santa was completely colored, but none of the women were. As he contemplated the picture, Dedini said, it seemed to him that if he applied flesh tones to all the women, there would be just entirely too much flesh color in the final rendering; so he stopped, hoping he would figure out a way to finish the coloring and avoid the monotonous hue. In the published cartoon, he made one woman’s skin lighter than another’s, and the third, positioned somewhat behind Santa, is tinged with green and gray as if in the half-light of the bedroom.

The other unfinished art depicted a

couple standing aghast in front of an elevator, which has just opened to reveal

a man standing inside, holding a bottle in one hand, with a zaftig woman

sitting on his shoulders, her legs around his neck. He says to the astonished

couple, “Did you ever go up in an elevator and forget what you went up for?” Complete

nonsense, of course. The joke, Dedini said, originated in that familiar

circumstance: “Did you ever get up to do something and forget what it was

before you got to it? Well, this guy ...” and he nodded in the direction of the

cartoon, his explanation dissolving into laughter.

At that, I couldn’t resist asking

the question that pesters every cartoonist: “Where do you get your ideas?” I

said.

“I’ll show you,” he said, and he got

up and went across the room and picked up a small square-spine sketchbook. He

brought it back, sat down next to me, and opened the book to show me. On the

pages of the book were pasted pictures clipped from magazines—advertising art,

photographs of landscapes or odd buildings, picturesque cottages, famous

paintings, portraits of medieval kings and queens, actors and actresses,

elaborate costumes, random designs. On the pages facing the pasted-in clippings

were Dedini sketches and notes. The sketches often echoed, without imitating

precisely, the clipped art on the facing page.

“See here,” Dedini said, pointing to

a clipped fragment of, say, a picture of an Arabian potentate in elaborate

turban and colorful cloak, “I thought there might be something in this ...” On

the facing page might be a drawing of a man’s head enveloped in a monstrous

turban dripping with jewels. Not yet a cartoon, just a funny picture. So far.

“I make these books,” Dedini continued, “and when I’m looking for ideas, I

thumb through these.”

He also consults his research

department—all those magazines stacked throughout the house. Once he saw a

spectacular two-page magazine ad spread for women’s clothes, gorgeous models

marching across two pages in a parade of fashion and femininity. “And I

thought, I’d love to draw that, the clothes, the girls,” he said, “—so I did.”

Just for the fun of it. And then, he drew a man in the line-up, and that

created a situation begging for a gag. He found the gag in the personal columns

of the Village Voice, which he

repeated verbatim in the cartoon, a deadpan recitation of the advertiser’s

search for a liberated roommate.

Dedini’s creative process often

began with visual images. Looking at other art or photographs, he played with

the images and the connections he could conjure up between those and some

fragment of conversation.

“Michelle says I should make my

women prettier,” he said, looking at the woman sitting on the man in the

elevator. “My women aren’t all that pretty, not like covergirls. But

they’re—okay. Just not beautiful. But they’re like real women that way. I told

Michelle that fashions change. And today, women—in movies, on tv, in

advertisements—look like ordinary women, not like movie stars. They look like

my women,” he said with a grin.

All the characters in the elevator

cartoon had been colored; everything else was stark white still. When

published, the interior of the elevator and the walls were colored muted grays

and browns, nothing, in other words, extravagant that would detract from the

pictures of the people.

There are doubtless several Dedini

cartoons in the Playboy inventory,

awaiting publication. The New Yorker also

has quite a store of Dedini cartoons. One of the things that puzzled him at the

time was that the magazine continued to buy cartoons from him but didn’t

publish them. One summer, he vowed he’d spend the next month concentrating on New Yorker humor, determined to break

into print there once again. But The New

Yorker still hasn’t published a Dedini cartoon since. A puzzle.

For the last month of his life,

Dedini stayed at home under hospice care which kept him relatively pain free

and comfortable. His son Giulio came from his home in San Luis Obispo and moved

in to stay with him and his mother. So did the cartoonist’s younger brother,

Delwin, 80, who still lives at the family ranch near Altadena. Friends dropped

by, and he enjoyed them, Giulio told me. Even though he hadn’t the stamina for

long conversation, Giulio said, “He makes us laugh every day.”

Dedini wanted his papers and

original art to be archived at Ohio State University’s Cartoon Research

Library. On Monday, January 9, Jenny Robb, Visiting Assistant Curator of CRL,

arrived to arrange packing up and shipping the materials. When she came in to

meet Dedini, he was delighted to see a pretty young woman, and, the eternal

gentleman, he sat up in bed right away to engage her in conversation. The

cartoonist was extraordinarily meticulous in maintaining the most comprehensive

of files. The White House note requesting the Jackie Kennedy cartoon is filed

with associated clippings and other correspondence about the final disposition

by auction of the original. So well organized was the material that it took

only a day-and-a-half to pack it all up in about 100 boxes. By the end of the

day on Wednesday, Giulio told me, the boxes and 2,000 originals were on a truck

bound for Ohio.

“I went in to tell him that it was

all done,” Giulio said, “—all his papers and his originals were safely on their

way—and he could rest easy now. And sure enough, the next day, he did. That’s

when he died.”

Reuben Pearson, a printer and poet

and a PBL denizen, described Dedini as “gentle and Italianesque, a wielder of

brush and Rapidograph, who viewed life through a twinkle and who must ever be

counted as one of Heaven’s creatures who are splendidly whole.” His eye lost

none of its twinkle: he kept on making people around him laugh every day, funny

to the last.

Here’s a too short gallery of Dedini cartoons.

NOUS R US

Popeye

is 77 this month: he debuted in E.C.

Segar’s Thimble Theatre on

January 17, 1929, just a ten days after the launches of Buck Rogers and Tarzan,

strips the antique histories of the medium used to cite as the watershed birth

of the adventure strip. They were only partly right in this contention. ...

Dark Horse Comics is twenty years old this year. It was born in the mind of Mike Richardson and on the counter of a

comics shop he owned in Beaverton, Oregon, where he and Randy Stradley pasted up the first issue of Dark Horse Presents, featuring work by Paul Chadwick (Concrete), Chris Warner (Black Cross), and Stradley’s Mindwalk, drawn by Randy Emberlin. ...

Perry Ellis, a sportswear company, will forsake photography in its fashion ads

in March to launch a new series of ads in comic strip form in Cargo, GQ, and Esquire. Cartooning in ads was nearly omnipresent fifty-seventy

years ago, but it faded with the expiration of such general interest magazines

as Collier’s and Saturday Evening Post; thanks to the new respectability conferred

on comics by graphic novels and hugely successful motion pictures, cartooning

in advertising is enjoying a renaissance.

Pulitzer-winning editooner Ann Telnaes won the 2005 National

Population Cartoon Contest, with a purse of $7,000. The contest rewards

cartoonists whose work occasionally emphasizes the perils of global

over-population. Telnaes’ entry, entitled “Washington Fashion Week,” was chosen

over 155 others; it depicts three runway models wearing dresses with

anti-condom, anti-abortion, and “stop sex ed” logos, a woman observer

commenting: “I hear disturbing patterns are in.” Telnaes’ cartoons frequently

tackle feminist issues, often the plight of women in Third World countries who

have no status or rights. ... Another Pulitzer-winner, editoonist Pat Oliphant, who now lives in Santa

Fe, New Mexico, went to Lexington, Kentucky to judge nudes in the 20th annual Nude International exhibition. Oliphant was a little daunted to find

that he was the sole judge: “I’ve been on a panel before where we all shared

the blame, but this is quite a shag on the rocks.” Oh—did I mention? The

exhibition was of figurative art, not flesh. Oliphant picked 106 works out of

846 pieces to judge. “The show is much better than I thought,” he said,

explaining that he’d seen only slides before getting to Lexington.

Apparently a new Golden Age of

Comics has dawned without much fanfare. Pratt Manhattan Gallery opened an

exhibit on January 20 entitled “Speak: Nine Cartoonists,” an event hailed at

cgw.pennet.com as a celebration of “the golden age of North American comics.”

The show displays the work of Ivan Brunetti, Charles Burns, Daniel Clowes,

Robert Crumb, Jaime Hernandez, Gary Panter, Seth, Art Spiegelman, and Chris

Ware. Not a Golden Ager among them. Curated by Todd Hignite, founder of Comic Art magazine—who doubtless did not

dub the contemporary ’tooning “golden” (or did he, trying to establish a new

beachhead?)—the exhibit runs through February 25. ... Homeland: The Illustrated History of the State of Israel, a graphic

novel that will tell the tale from Biblical times to the present, will be out

in May, published under the auspices of the Community Foundation for Jewish

Education of Metropolitan Chicago. Veteran comics scribe, Marv Wolfman, is writing the story, which will be ecumenically

rendered by Mario Ruiz, an

evangelical Christian and president of Valor Comics. William Rubin, the

Foundation’s CEO, was inspired to foster the project partly by his 9-year-old

son, who reads Harry Potter before

going to bed, and partly by the increased respectability of the comics medium

in its graphic novel manifestation. After devoting approximately 20 percent of

the book’s pages to Biblical and post-Biblical history, the remaining 80

percent will cover 1860 until today. Aware of Israel’s often controversial

past, the creators intend to include the warts as well as the wonders, hoping

to head off the inevitable criticism that will challenge the book on its

representation of the facts.

A comic book in Central America’s

Belize is called Torn Pages and tells

stories of incestuous relations, gang rape, sexual harassment, white slavery,

and sexual abuse. The book is not intended to amuse: its sponsor, Youth

Enhancement Services, and its illustrator, Charles

Chavannes III, hope the stories will help some teens cope with some very

traumatic events in their young lives. ... Chartered Bank Malaysia is offering

new credit cards emblazoned with the images of Batman, Bugs Bunny, Tweety Bird

and the Tasmanian Devil, hoping the promotion will sign up 30-50,000 new

cardholders in six months. ... Director Ron Howard’s daughter, Bryce Dallas

Howard, is reportedly in talks to play the part of Peter Parker’s highschool heartthrob, Gwen Stacy, in the third

Spider-Man movie; the rumor is already being touted about that in this version

of the events of Amazing Spider-Man No.

121, Gwen survives. I don’t believe for one minute that they’ll actually pull

this off; that’d be tampering with holy writ.

Interviewed at dynamicforces.com, Frank Cho was asked which of his two

zaftig creations, Brandy in Liberty

Meadows or Shanna in the Marvel comic book, he enjoys drawing more.

“Depends on my mood,” he said. “Of late, I enjoy drawing Shanna more. Shanna is

such a wild and uncharted character. I already have a list of do’s and don’ts

for Brandy, but with Shanna, sky’s the limit.” He admitted that he misses doing Liberty Meadows “desperately, but

Marvel is letting me play with so many cool toys that it takes much of the

sting away [currently, the New Avengers,

written by Brian Michael Bendis].

People have to remember,” he continued, “just because I have time only to draw

Marvel characters at this point doesn’t mean that I stopped writing for my own

creations. Right now, I’m writing and saving all the stories for my future

creator-owned books.” Then he was asked if there was one female actress in the

world that could be your very last drawing, who it would be. “It’s a toss up,”

Cho said. “Bettie Page or Louise Brooks. Besides timeless beauty, both have

that indefinable ‘spark,’ the intangible quality that draws the viewers in and

wants men to possess them.” Bettie Page didn’t surprise me much, but Louise

Brooks did.

“Brooksie,” as she was known during

her notorious first seasons in New York in the 1920s, came to the Big Apple

from Kansas, the heart of the Bible belt, where she was born in 1906. She

became the youngest chorus girl in George White’s stage show, the “Scandals”

(described as “a racier, skimpier version of the ‘Follies’” in Jerome Charyn’s Gangsters and Gold Diggers), where she

wore “light bandages.” In 1926, Photoplay magazine described her: “She is so very Manhattan. Very young. Exquisitely

hard-boiled. Her black eyes and sleek black hair are as brilliant as Chinese

lacquer. Her skin is as white as a camelia. Her legs are lyric.” Anita Loos

called her “a black-haired blonde” with a “blonde personality,” her famous bob

hair-do was the official party-girl cut of the day. Her beauty and the brevity

of She had an affair with Charlie

Chaplin and then went to Hollywood where she was quickly albeit briefly a star,

leaving when Paramount denied her request for a raise and going next to Berlin

to play the legendary folk seductress Lulu in the celebrated silent 1928 film

“Pandora’s Box” in which the femme fatale Lulu seduces every male in sight and

is then killed by Jack the Ripper. Back in Hollywood, she refused to dub one of

her silent movies and was blackballed. Sometime in the thirties, Brooksie

disappeared, dropping out of sight, a casualty of her refusal to play by

anyone’s rules. She worked variously in non-theatrical jobs, was kept by

admiring moguls from time to time, and, at the end of her life, wrote articles

about her adventures in filmland. Collected, eventually, in Lulu in Hollywood, the articles reveal

an engaging writing talent, an ambiguous lyricism coupled to candid revelations,

dripping with insightful anecdotes about the actors and writers she hobnobbed

with.

Brooksie was also, in her heyday, a

cartoon character: she was the model for Dixie Dugan in illustrator John H. Striebel’s comic strip of that

name. Written by comedy writer J. P. McEvoy, the strip was inspired by his 1927 Liberty magazine serial, Show Girl. The strip debuted under that

name in 1929 and lasted over thirty years, but its beginnings are part of

another scrap of cartooning lore, this one attached to Joe Palooka. Ham Fisher,

Palooka’s creator, had been peddling his strip about a prize fighter for ten

years, off and on, without success. Finally, one day in 1929, he ran into

Charles McAdam, general manager of the McNaught Syndicate, who promised to give Palooka a try the next year. Fisher

insisted on going out himself to sell his strip; he apparently had little faith

in syndicate salesmen doing right by his creation. McAdam was dubious. So

Fisher, to prove his ability as a salesman, undertook to sell one of the

syndicate’s losers, Show Girl. It had

been offered around before but had been picked up by only two newspapers.

Paying his own expenses, Fisher went on the road and sold the strip to

thirty-some papers in forty days. When he returned and wanted to repeat this

performance with his own strip, McAdam demurred. Fisher was so good at sales,

McAdam said, he would be more of an asset to the syndicate as a salesman than

as a cartoonist. But Fisher would not be denied. He waited until McAdam went on

vacation, and then he took Joe Palooka on

the road and sold it to twenty papers in three weeks. Joe Palooka began national syndication in April 1930. Ron Goulart, in his history of 1930s

adventure strips, The Adventurous Decade,

reveals something of the secret of Fisher’s success as a salesman. He quotes

from the autobiography of Emile Gauvreau, editor of the New York Graphic before becoming editor of William Randolph

Hearst’s New York Mirror: “I bought

my last comic strip one New Year’s Eve when Ham Fisher ... befuddled me with a

bottle of rare bourbon during a hilarious celebration. When I woke the next

day, I found I was sponsor of Joe Palooka,

an exemplary character who never drank or smoked and was good to his mother.”

Meanwhile, Show Girl changed its name

to Dixie Dugan, probably with the

release of October 29, 1930, enjoying under that rubric a long run until 1962.

And while we’re loitering in this

vicinity, I remind you that Goulart’s book, aforementioned, has just been

re-issued, this time profusely illustrated. The text alone was, and is,

invaluable. But now, amply illustrated—often from original art—the book is a

veritable treasure trove of comics history. In this incarnation, the book is

9x12", bound on the short side, so its pages amply display at generous

dimension the horizontal art; and occasionally, strips in their original art

are printed across two-page spreads, probably at close to the size of the

originals. In his short introduction, Goulart says he did not revise any of the

text of the 1975 edition, but he notes and corrects “the few errors of fact and

judgment” that he has become aware of. The pictures in this edition are equal

to the text as insightful history, at just $24.99, a bargain hard to come by in

these days of so much slapdash, haphazard, ill-informed history, like

DeForest’s book, discussed below.

My. Looking over this last segment,

beginning with the Cho quotes, I think we have here, in its loping ramble, a

miniature of Rancid Raves itself—news, quoted from the horse’s mouth, some social

history and cartooning lore, plus a book review. The whole enchilada in a

capsule. I feel like Lawrence Sterne.

Animation News. Likely candidates for the Oscar in animation are “Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride,” “Wallace &

Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit,” and “Howl’s Moving Castle”—none of

which, we hasten to aver, are computer-generated. Traditional animation may log

another win for sheer stamina, not to mention excellence, and antique tradition

at that: all three of these flicks use more primitive means of production than

hand-drawn animated cartoons—namely, stop-motion photography of puppets and

clay figures.

Disney is in negotiation with

Apple’s Steve Jobs to buy his Pixar, and the guessing in the recent past was

that if “Chicken Little” did well at the box office, the Mouse House would have

the edge in the exercise. But the Chicken didn’t come home to roost, and if the

prognosticators of yore are right, then, Jobs has the advantage. The Wall Street Journal reported that the

deal in the works has Disney buying Pixar with $6.7 billion in stock; if so,

that would make Jobs the company’s largest single stockholder. With this much

clout, he’d be in a position to influence Disney’s animation agenda, which has,

at last, followed Pixar’s lead into computer-generated movies. Of the ten top

grossing animated films since “Toy Story” debuted in 1995, all but one

(Disney’s” Tarzan”) have been computer-generated (CG). Pixar’s “The

Incredibles” in 2004 brought in $630 million, almost as much as Disney’s last

eight animated movies combined. Disney saw the handwriting on the wall writ

large and started converting from pencils to pixels, reducing its animation

staff from 2,200 to 725.

A reluctant leader in the conversion

was Glen Keane (son of Bil Keane, father of The Family Circus), at 31, a veteran

animator with impressive credits (“The Little Mermaid,” “Beauty and the Beast,”

and “Tarzan”) that established him with the devotees of the Disney religion,

hand-wrought animation. Promised that he could direct a favorite project of

his, “Rapunzel Unbraided,” if he did it with a computer, Keane sat down to

learn CG. And he discovered, perhaps to his surprise, that it made him a better

artist. Said he: “It challenged me to be better at what I do.” It also enabled

him to do something he couldn’t have done by hand—give Rapunzel freckles. With

Keane converted, others who had been clinging to the Disney tradition started

coming over. The next three big animated films will be CG: this year’s “Meet

the Robinsons,” next year’s “American Dog,” and, in 2008, Keane’s “Rapunzel.”

Fascinating as all this is, the real

poser in the pending Apple-Disney lash-up is what Jobs might do with his clout

to marry online content, computer hardware, and digital distribution. Jobs,

remember, is the guy who created a hip alternative to the IBM desktop computer,

launched a pocket digital music phenomenon, and sent the standard for CG film.

Gina Keating at Reuters writes: “Jobs could conceivably exert his new-found

influence at one of America’s biggest content companies—home to ESPN, ABC-TV,

and Walt Disney Studios—to feed Apple’s digital music and video download

service iTunes.” She quotes analyst Jeff Logsdon of Harris Nesbitt, who said:

“In our view, no company understands both technology and the consumer better

than Apple. ... [If Jobs gets on Disney’s board], that certainly brings one of

our generation’s more innovative applied technologists into their umbrella.”

The mind, as is its wont these days, boggles. But even if the merger doesn’t

happen, chances are good that Disney, now that Michael Eisner has evaporated,

will maintain good relations with Pixar, and that bodes plenty of innovation

for the rest of the Internet Age.

FOUR-COLOR LONG-JOHN LEGIONS:

IMPRESSIONS AND PEEVES

A

propos of nothing whatsoever, I made a list the other week of the superheroes

that first sprang to mind when I remembered reading funnybooks as a kid back in

the late 1940s and early 1950s. Superman, Batman—and Robin in his solo gig in Star Spangled Comics —Wonder Woman, Green

Arrow, Green Lantern in his purple and green cape, Hawkman, the old Flash in

his tin helmet, Captain Marvel and the rest of the Marvel Family, Lev Gleason’s

Daredevil with his two-tone tights and spikey belt, Captain America, Plastic

Man, Dollman, Hoppy the Marvel Bunny. That’s about it. I read other comics— Tom Mix, Boy with Crimebuster in his

short pants accompanied by his pet monkey Squeeks, the Fox and the Crow, Walt Disney Comics and Stories with the

Bad Little Wolf and Mickey Mouse adventures in the back pages, Donald Duck, Blackhawk, Looney Tunes with Bugs and Mary Jane and Sniffles and Bucky and Bo Bug (particularly Bo),

George Pal’s Puppetoons. Others. But

the superheroes I remember are mostly those I just listed. There were many

others: they just don’t spring to mind as readily.

After making my list of Golden Age

superheroes, I quickly jotted down the heroes of the Marvel Universe I whose

names surfaced soonest. Iron Man, Daredevil with the toothsome Black Widow.

These are the ones I started on when I returned to comics in the early 1970s. I

didn’t get into the others much, but their names showed up on my list right

away: Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Doctor Strange, Thor, the Hulk, Nick Fury

(mostly because of Jim Steranko’s treatment of the medium in that title), then

the X-Men—Cyclops, Phoenix, Storm, Wolverine. During my monthly thumb through

the pages of Previews, it seems to me

that Marvel somewhere along the way developed a severe case of arrested

development: its comics are still pretty much all superhero titles. Some of

them have been revitalized a little in recent years, but still—nothing much

beyond spandex. Nothing like DC’s 100

Bullets, Y: The Last Man, Fables, Loveless, The Exterminators, even Gotham Central. Nothing as adventurous as

DC’s Milestone off-shoot or Alan Moore’s America’s Best Comics. Just

superheroes, more and more jazzed up as time winds on but, still, just

superheroes. Adding Stephen King to the Marvel roster of writers yields a new

title with a non-superheroic bent, but one series of books does not a swallow

make.

Marvel is typical of the industry,

which, judging from my Previews thumb-through,

is running along some fairly pretty well-worn ruts. Apart from the men in

tights, there are the women in tights, and their tights are tighter than the

men’s, clinging like skin to their generous embonpoint. Basketball bosoms

abound. In a country where sex appeal sells like nothing else, the prevalence

of zaftig femmes in comic books is scarcely surprising. Wherever you don’t see

the superheroic, you see the supernatural—zombies and vampires and gruesome

phantoms from the nether regions. On nearly ever other comic book cover, we see

faces distorted in horror or in grim, teeth-gritting determination. Serious

stuff indeed. And then Previews gives

us page after page of manga, an infestation of wispy-haired, big-eyed cuteness

so colossal that it threatens the zeitgeist of the culture.

Years ago during my novitiate as a

comics critic in the late 1970s, I wrote a long piece about DC Comics entitled

“DC Means Dull Comics.” I’m happy to report that’s no longer the case. Of the

Big Two comics publishers, DC is by far the more innovative. Image is probably

the next most venturesome, followed by Dark Horse, where the distinctive factor

is the company’s proven ability to tie-in to other realms in the entertainment

industry, chiefly motion pictures. But Marvel seems stuck in the groove that

its prolific editor Stan Lee ground out for it when he revolutionized

superheroics in the 1960s by imbuing the characters with actual human

personalities.

Andrew McGinn at the Springfield News Sun recently listed Lee’s “best

moments,” the top ten of his legendary achievements. These include, working

from the bottom to the top, the marriage of two of the Fantastic Four, the

elastic Reed and invisible Sue, in FF

Annual No. 3; the 18-issue run of The

Silver Surfer, a near Biblical character who comments on the human

condition; the origin of Daredevil, a blind lawyer (“blind justice,” eh?); the

invention of the X-Men, an analogy of the civil rights struggle in which

mutants with special powers are persecuted by the rest of the human species (or

is it teenagers put upon by adults?); Fantastic

Four No. 51, in which the relationships among the quartet are examined; FF Nos. 48-50, wherein our heroes meet

something that can’t be beaten and so confront it, the giant Galactus, who

intends to swallow the earth whole, people and all; the resurrection of Captain

America in The Avengers No. 4; the

anti-drug story in The Amazing Spider-Man

Nos. 96-98, requested by the White House, rejected by the Comics Code, but

published by Marvel anyhow in courageous defiance of the Code in the name of

social welfare; the 1962 invention of Spider-Man, the angst-plagued teenager

who learns that “with great power there must also come great responsibility”;

and the 1961 origin of the Fantastic Four, super-powered beings who bicker and

otherwise reveal that they are, after all, human.

Looking back over the list, it’s

astonishing to realize how little of comparable magnitude in the four-color

domain has been accomplished since. The artwork has improved spectacularly over

the last couple decades. Some of the best illustrative work in the country is

now being done in comics. But the themes of comic books have remained largely

unchanged since Stan Lee with the able and indispensable visualizing

collaboration of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, conducted his revolution in the

1960s. The authentic maturation of the medium represented by the advent of graphic

novels with their stories exploring the human condition has taken place almost

entirely outside the realms presided over by the major comic book publishing

houses.

In those realms, as Andrew Smith

notes in The Comics Buyer’s Guide No.

1613 (February 2006), certain trends are revisted again and again until

they “get so omnipresent that they become absolutely tiresome.” He discusses

the three that most annoy him: teenage melodrama, lesbian chic, and the

“revolving door of death.” I agree with him on all three counts. Once

publishers discovered that adolescent angst appeals to youthful readers, they

flooded the newsstands with titles that examine and agonize over the sorts of

teenage agonies that “evaporate by age twenty.” As the current deluge of manga

books demonstrates, young readers are drawn like moths to the flame of stories

that dwell endlessly on oxymoronic juvenile catastrophe, but this game offers

little that appeals to adult readers. Smith also confesses to being bored “by

the fad of shoe-horning homosexual women into every conceivable title. It

doesn’t help that a lot of it is played for shock and/or titillation, which

ought to annoy readers of any and all opinions on the subject because that’s

lazy writing. But what really annoys me is the mind-numbing repetition—writer

after writer, book after book, pretty much telling the same story, over and

over.” Smith’s negative attitude is not homophobic, he claims—and I believe

him—but simple boredom. The surprise “outing” of a lesbian character happens so

often, he says, that he’s no longer surprised. Or shocked. The device thereby

loses its dramatic impact, and without drama, the story has no power to

enlighten readers or change their attitudes. Finally, even death loses its

dramatic power when a character is killed in one issue and then, six months

later, is discovered not to have died at all—or is revived by some miraculous

contraption. Writers who resort to killing off characters as a way of shocking

or engaging readers reveal only the poverty of their imaginations. Says Smith:

“Death has been overdone. It’s a lazy cliche. It’s just been done to, ahem,

death.”

Ouch, but—yes.

COMIC STRIP WATCH

Up