| |

It’s the Pictures, Stupid

Not to Mention Bondage and Grecian Urns

One

of the side-effects of the dubious renown that attaches to a chronicler of

comics history comes in the form of phone calls from strangers purporting to be

newspaper reporters who have been assigned to write an article about the

funnies. Among the first questions asked is one that goes something like this:

Why are people so in love with the comics? What is it about them?

I’ve had this question sprung on me

more than once, but it always catches me wholly off-guard, like a naked man in

the headlights of an onrushing deer. Well, that’s a little extreme maybe, but

the question catches me up short and gives me a sinking feeling in the stomach:

unaccustomed as I am to being at a loss for a thought, I can think only that

I’ve never thought of that before. I never have on the tip of my tongue

anything like the sort of penetrating, deep level analytical apothegm that

readers of Rancid Raves have doubtless come to expect hereabouts.

Partly, my dumbfoundedness prevails

because it has always seemed to me self-evident why the comics are so popular.

Asking me why the comics are popular is like asking me why standing under a

summer sun makes one warm. Milton Caniff may have put his finger on it when he

said, once, “Whatever it is that makes a popular art effective—escape, or the

appeal to basic emotions, or ‘audience identification’—the funnies have it, and

they have more of it than any of us ever suspected.”

In other words, he didn’t know

either. Or couldn’t say.

When asked this question, I usually

mutter that we (“people”) like the funnies because, through repeated

visitation, the characters become almost members of our family—old friends, at

least—and we like the easy familiarity of the company of old friends and family

members. And if, by then, I haven’t fallen asleep out of sheer boredom at the

mindless tepid banality of this analysis, I might have collected my wits

sufficiently as I speak to remember, suddenly, that the Big Appeal of the

funnies is that they make us laugh, and we all enjoy laughing—ergo, we turn

eagerly, day after day, to the comics section of the newspaper before it even

occurs to us to consult the editorial page where all the truly important

utterances are taking place. We’d rather laugh than think any day.

Actually, I usually leave out the

last part about the editorial page. No point in annoying my interlocutor by

rubbing his or her nose in journalism’s signal failure—namely, its inability to

make its readers take news seriously enough to displace comic strips at the top

of the hierarchy of their interests in the newspaper.

Nor do I point out, gleefully, that

their question sabotages a fiction to which newspaper editors have subscribed

for generations in willful disregard of the facts. Editors say they think

comics are for children, but that’s not what they really think. They really

think, as I said, that they’ve failed to make their readers take news

seriously, and since news is their business—their profession—they cover up

their bitter disappointment at their own shortcoming by pretending that it

isn’t their readers who ignore the news and read the comics but the children of

their readers. Their readers, they fantasize (completely dismissing the results

of readership surveys), are actually reading the front page of the paper and

studying the editorials and forming adult opinions that they will subsequently

translate into votes at the ballot box come Election Day.

Most readers of daily newspapers

would, if asked, tell these editors that the only reason they stop on the

editorial page as they flip through the paper on their way to the funnies page

is that a large cartoon at the top of the editorial page attracts their

attention momentarily. Editors know this, too, although they don’t like to

admit it. The closest they come to acknowledging the appeal of cartooning is to

try to prevent their editorial cartoonist from drawing cartoons that are too

opinionated, the sort of cartoons that Might Offend one group or another of the

readers that aren’t reading anything else on the editorial page.

By happy coincidence, the undeniable

appeal of the editorial cartoon comes closer to explaining our emotional

attachment to comics than anything else I’ve said so far. One of the best

exegesis of the relationship between humans and pictures was made nearly sixty

years ago by a psychologist, who, at the time he offered his explanation, was

concocting stories for a comic book character he’d created, Wonder Woman.

Writing in The American Scholar (January 1944), William Moulton Marston, with degrees from Harvard, titled his

article “Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics.” Among his other accomplishments,

Marston was author of the book Emotions

of Normal People (1928) and discoverer of the lie detector and was

therefore admirably equipped to confront the truth about comics and their

readers.

“Nine humans out of ten react first

with their feelings rather than with their minds,” Marston wrote. “The more

primitive the emotion stimulated, the stronger the reaction. Comics play a

trite but lusty tune on the C natural keys of human nature. They rouse the most

primitive but also the most powerful, reverberations in the noisy cranial

sound-box of consciousness, drowning out more subtle symphonies.” Quite simply,

he goes on, people are enthralled by comics because of the pictures. After a

half-century of television, we no longer require extensive argument to be persuaded

of the truth of this assertion. But in 1944, Marston felt the need to go into

the matter at some length:

“The potency of the picture story is

not a matter of modern theory but of anciently established truth,” he said.

“Before man thought in words, he felt in pictures.” Referring to articles by

M.C. Gaines (“Narrative Illustration” and “Good Triumphs over Evil”), Marston

continues: “The ancients, as numerous historical monuments attest, recorded

their military triumphs as well as their domestic comedies in picture stories.”

After noting that “the visual form must be simplified to essentials, the

emotional response evoked must be instant and universal,” Marston careens away

in the direction of explaining the fundamental appeal of superhero comic books.

He begins by tracing, briefly, the history of pictorial narrative and divides

the “evolution of comics” into three periods: in the first, 1900-1920, comics

were almost entirely meant to be funny; but in the second period, 1920-1938,

comics introduced “pathos and human interest” into stories that continued from

day-to-day, ceasing, eventually, to be funny and becoming adventure stories.

The third period began in 1938 with

the debut of Superman, whose arrival “constitutes a radical departure from all

previously accepted standards of storytelling and drama. Comics continuities

[i.e., comic books] of the present period are not mean to be humorous, nor are

they primarily concerned with dramatic adventure. Their emotional appeal is

wish fulfillment. There is no drama in the ordinary sense because Superman is

invincible, invulnerable. ... Superman never risks danger; he is always, and by

definition, superior to all menace. Superman and his innumerable followers

satisfy the universal human longing to be stronger than all opposing obstacles

and the equally universal desire to see good overcome evil, to see wrongs

righted, underdogs nip the pants of their oppressors, and, withal, to

experience vicariously the supreme gratification of the deus ex machina who accomplishes these monthly miracles of right

triumphing over not-so-mighty might. Here we find the Homeric tradition

rampant—the Achilles with or without a vulnerable heel, the Hector who defends

his home town from foreign invaders, wronged Agamemnon who pursues his

righteous vengeance with relentless fury, and the wily Ulysses who cleverly

accomplishes the downfall of attractive if culpable enemies by the exercise of

superhuman wisdom. M.C. Gaines ... perceived the Homeric inheritance of Siegel

and Shuster and ... turned the comics magazine into an illuminated vehicle for

their drama-less but wish-fulfilling Superman tales.”

Having established the

wish-fulfillment nature of four-color superheroicism, Marston next asserts the

morality of the medium. “What life-desires do you wish to stimulate in your

child?” he asks.

Surely youngsters should be

encouraged to “wish for power along constructive lines. ... The wish to be

super-strong is a healthy wish, a vital, compelling, power-producing desire”

involving “the child’s natural longing to battle and overcome obstacles,

particularly evil ones. ... Certainly, there can be no argument about the

advisability of strengthening the fundamental human desire, too often buried

beneath stultifying divertissements and disguises, to see good overcome evil.

‘Happy’ endings are shown in the new comics as products of superhuman efforts

to help others—not as mere happenstances mysteriously obeying the ‘Pollyanna’

rule that ‘everything always comes out all right in the end.’ The moral force

of this new type of story teaching is stronger by far than the older appeal to

self-interest. ... The Superman-Wonder Woman school of picture-story telling

emphatically insists upon heroism in the altruistic pattern.”

That Marston’s essay veers off into

a defense of comic books—then, as ever since their beginning, under attack by

“concerned citizens” and “parents groups”—is not surprising. Not only was he

writing one of the titles, he had, for some years, been on DC’s advisory board

of educators, a roll call of distinguished personages in professorial garb

charged with analyzing “the shortcomings of monthly picture magazines and

recommending improvements,” which resulted, Marston goes on, in raising

“considerably the standards of English, legibility, art work, and story content

in some twenty comics magazines, totaling a monthly circulation of more than

six million.”

The only flaw in the array of

newsstand comics before 1942, the year Wonder Woman debuted, is, Marston says,

“their blood-curdling masculinity. A male hero, at best, lacks the qualities of

maternal love and tenderness which are as essential to a normal child as the

breath of life.” To rectify this oversight, Marston proposed that a superwoman

be invented “with all the strength of a Superman plus all the allure of a good

and beautiful woman.”

Marston’s advocacy for the feminine

mystique was not entirely philosophical, as we learn in Les Daniels’ Wonder Woman: The Complete History (2000).

The good doctor believed, as early as the interview he gave November 11, 1937,

to The New York Times, that “the next

one hundred years will see the beginning of an American matriarchy—a nation of

Amazons in the psychological rather than physical sense” and that eventually

“women would take over the rule of the country, politically and economically.”

Marston later elaborated: women would rule the world because “there isn’t love

enough in the male organism to run this planet peacefully. Women’s body

contains twice as many love generating organs and endocrine mechanisms as the

male. What woman lacks is the dominance or self assertive power to put over and

enforce her love desires.” Earlier, he theorized that woman would achieve

dominance over man because “her body and personality offer men greater pleasure

than they could obtain in any other experience. Man therefore yields to this

attraction and control voluntarily and seeks to be thus captivated.” In short,

women would achieve power through simple sexual enslavement. That Marston was

the sort of professional to whom heed must be paid on such matters is evident

in his own life. He lived with two women, one, his wife Elizabeth, and the

other, a former student named Olive Byrne who was subsequently Marston’s

assistant and colleague, and he had children with each of them. According to

one of Olive’s sons, Byrne Marston, interviewed by Daniels, they all lived

together “fairly harmoniously.” Olive never married, and Byrne and his brother

were eventually formally adopted by the Marstons. Elizabeth once claimed that

she suggested the notion of a superwoman to Marston. Byrne believes that his

mother, Olive, was the physical model for artist Harry Peter’s rendition of

Wonder Woman; Olive, it seems, also affected a wardrobe accessory that

influenced the conception of the heroine—big silver bracelets, one on each

wrist. Given Marston’s theory about the dominance of the female personality, I

was amused to learn, from Daniels’ quoting Marston’s editor Sheldon Mayer, that

the Marston household was “male-dominated” even though Marston himself was

clearly out-numbered.

Wonder Woman, for all her appeal,

never quite lived up to Marston’s visions for female dominance of the known

world. And she has always, from the very first, been a difficult character for

comic books. The audaciousness of Marston’s proposal for a superheroine “was

met by a storm of mingled protests and guffaws.” Heroines, Marston was told,

had been tried before and had failed to attract readers. Yes, but, Marston

reposited, those female heroes hadn’t been superpowered.

Despite the seeming impracticality

of the idea, Gaines, Marston says, “listened to our arguments for a while. Then

he said:

“‘Well, Doc, I picked Superman after

every syndicate in America turned it down. I’ll take a chance on your Wonder

Woman! But you’ll have to write the strip yourself. After six months’

publication, we’ll submit your woman hero to a vote of our comics readers. If

they don’t like her, I can’t do any more about it.’”

“Fair enough,” Marston said to

himself, and he then “found” an artist—“Harry Peter, an old-time cartoonist who

began with Bud Fisher on the San

Francisco Chronicle and who knows what life is about, and with Gaines’

helpful cooperation we created the first successful woman character in comics

magazines.”

At first, she bore the awe-inspiring

name “Suprema,” which, as Daniels remarks, got swiftly and mercifully lost on

the way to her first published appearance in All Star Comics, No. 8 (cover-dated January 1942).

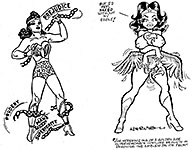

Peter, I hadn’t realized, was

probably in his sixties when all this transpired. He’d been dabbling in comic

book illustration somewhat, but his early post-Fisher career had been in gag

cartoons for periodicals like the humor magazine Judge. His drawing style, for the comic book medium, was unusual:

at a time when house styles were overpowering individual mannerisms, Peter’s

style was distinctive. And it remained so throughout his tour on Wonder Woman.

To a bold linear treatment, he affixed a fussy preoccupation with

details—eyeballs and eyelashes, and the curlicue of hair-dos—and a rather vague

understanding of female anatomy, including a conspicuous affection for

collarbone delineation and a tendency to model forms in places where there were

no places in real life. He perfected a way of drawing women’s lips, however,

and having got it right once, he did it in the same way forever thereafter.

And as any reader of the

Marston-Peters canon can attest, Marston (writing as Charles Moulton, his

middle name and Gaines’) added to the “allure of a good and beautiful woman”

plenty of “sly but imaginative psychological themes, especially those dealing

with domination and subservience” (as Gerard Jones puts it in Ron Goulart’s Encyclopedia of American Comics). In

addition to bondage, Marston also “played with some noble philosophic themes,

especially the conflict between ‘the cruel despotism of masculine

aggressiveness’ and the humane ways of women.” But the prevailing impression of

Wonder Woman’s escapades is “a heady brew,” Goulart says, “of whips, chains,

and cockeyed mythology.”

Oddly—considering the mythological

bent of Marston’s tales—the result of Peter’s effort was an imagery that

conjured up memories of the kind of painting we can see on ancient Greek vases.

(I say “oddly” because I hope no one takes this stylistic quirk to heart and

subsequently manufactures a vast new thematic import for the Marston-Peter

team-up on the Amazon in the spangled foundation garment. A more pertinent and

productive line of reasoning would concentrate on the foundation garment.)

All of which is somewhat beside my

present point—which is, lest you’ve forgotten, to elucidate the reason for

newspaper readers’ enthrallment by comics. And I don’t think we can improve

much upon Marston’s contention that we are captivated by pictures. They appeal

to a primitive aspect of our fundamental nature, taking us, momentarily, back

to the age of primordial ooze when a sense of sight was the most acute of our

senses and kept us alive as well as entertained. We can’t escape—nor should we

try—our basic natures.

And if I had a better memory, I

could have summoned this interpretation to respond to the reporters’ queries

without resorting to Marston. The first book I ever read on the comics was

1947's The Comics, by Coulton Waugh,

who, right near the beginning of the book, says, “[Comics] have taken advantage

of the ancient fact that a picture carries a thought faster than a group of

words, and this is the reason why they have been so enormously successful. Man

has always resisted the labor of thought, and the strips take a short cut to

the mind of the reader without much effort on his part. Since cave men drew

pictographs on bone and on cave walls, this new language is based on one of the

oldest means of communication in the world.”

True, no doubt, but there’s also

laughter and old friends.

Footnit: A slightly

shorter version of this essay appeared in The Comics Journal.

Return to Harv's Hindsights

|