THE MAKING

OF THE WESTERN MYTHOLOGY

And the Two

Frauds Who Helped It Along

In the Hall of

Statues just off the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., each

state is permitted to place statues of two of its native sons whose lives or

works were somehow worthy of enshrining. These bronzed personages on pedestals

include presidents and statesmen and generals—Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson,

Robert E. Lee, and so on. Exactly the kind of roll call you'd expect. Until

you get to Montana.

Montana's

two statues are of Jeannette Rankin and Charles M. Russell. Never heard of

’em, you say? How can they be heroes if they're unknown? Depends on your idea

of heroism, I guess.

Jeannette

Rankin (1880-1973) was a leader in the women's suffrage movement and in 1917

became the first female member of the U.S. House of Representatives. She

served until 1919 and was one of only 50 members of the House to vote against

declaring war on Germany. She was back in the House in 1941, and when war was

declared on Japan following the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, she voted against

the declaration—and this time, she was the only dissenting vote. Why? She was

a pacifist, first of all; but she also felt that "a good democracy"

should not be on record as voting unanimously for war.

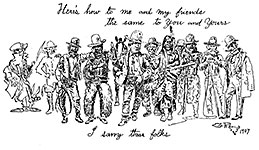

Charlie

Russell (1864-1926) is renowned as the self-taught "cowboy artist"

whose depictions of the old West in watercolor, oil, pen-and-ink, and in clay

and bronze sculptures are highly regarded for their authenticity. And for

their sense of humor. Before he became famous as an artist, Charlie hunted and

trapped, herded cows, and broke broncs. One winter, he lived with the Blood

Indians in Canada. They gave him the name "Ah-wah-cous," or antelope

(possibly because the pattern of his riding breeches in the back reminded them

of the south end of an antelope running north). Charlie always spoke of

Indians as the only "real Americans," and he was an early

conservationist and environmentalist (before there was such a term).

A

pacifist equal rights advocate and an artist. With heroes like these, Montana

is my kind of place.

Russell's

is the only statue of an artist in the Capitol. Fittingly, the only artist

monumentalized in the Capitol is a cowboy artist: the West, after all, is the

most distinctive aspect of American cultural history, and the history of the

country's expansion into the West—and the legends and lore associated with that

expansion—is the nation's mythology.

We

call this mythology “the Western.” The classic formula— a lone sometime gunman

rides into town and single-handedly defeats the land-hungry mogul or the

marauding band of bad guys or the lurking tribes of blood-thirsty natives— the

formula embodies the spirit of the American experiment. Like the American

political experiment, the Western champions the individual: the former

guarantees his rights; the latter trumpets his prowess, his fitness.

Like

any good literature, the American mythology contains an animating conflict.

Unlike most literature, however, the conflict in this mythology seldom, if

ever, surfaces. The conflict is between the individual and society, a conflict

inherent in the contradictions of the formula. Individual rights are

guaranteed by the rule of law; individual prowess, by the rule of individual

might. Each threatens to destroy the other; neither can triumph while the

other survives.

The

myth manages this contradiction by never confronting it. The myth insists that

the solitary champion emerge only when the rule of law has been overthrown.

And, once order is restored, the champion rides off into the

sunset—alone—leaving society to thrive now that the rule of law has been

reinstated.

Whether

the champion could himself thrive under the rule of law—whether he would, in

effect, submit to being ruled by something other than his own sense of justice—

is a question never actually examined. After all, the champion usually

believes in the rule of law and enacts its spirit (if not its letter). But

with all the power and resourcefulness he represents, he could, if he wished,

stand against that rule. But in our mythology, he never does.

We

invent him in a way that insures that the contradiction never arises.

Invention

is the literary version of fraud, and, fittingly enough, two famous persons

intimately associated with the American Western are made-up people. They

invented themselves, and in so doing, they made themselves the heroes of their

own, personal mythologies. But under the gloss of literary invention, they

were both hoaxes.

One

of them—a magnificently appropriate happenstance, a colossal stroke of poetic

justice—was the first King of the Celluloid Cowboys, a champion fraud in the

tinsel capital of make-believe. Tom Mix (1880-1940).

Mix

was, above all else, a showman. In his movies, he created with flash and

action and costume, the movie cowboy. The power of the motion picture lies in

its ability to blur the line between reality and illusion, and Mix set about

doing just that. His big screen personality defined the future for the

Hollywood Western.

And

in his personal biography, he defined himself. In his version of his life, he

was the epitome of a soldier of fortune: he went to Virginia Military Academy,

fought in the Spanish American War in Cuba, joined the marines, went to China

to fight in the Boxer Rebellion and was wounded in the chest, returned home,

recuperated in time to go to South Africa to fight in the Boer War, and, when

back in the U.S. again, accepted numerous lawman assignments throughout the

West. He was back in uniform for the Mexican troubles in 1915 or thereabouts,

and he somehow acquired all the riding, roping, bronco-busting, sharp-shooting

skills of a cowboy so that when he arrived in Hollywood, he was ready to assume

his on-screen persona.

Actually,

Tom Mix never attended the Virginia Military Academy, and although he did

enlist in the army at the outbreak of the Spanish-American hostilities, he

served in a regiment whose job was to guard the DuPont powder works in

Delaware. He saw no action. He re-enlisted in 1901, though, hoping to get

sent to South Africa but wasn’t. Disappointed at this unglamourous turn of

events, Mix deserted and took off for the West.

In

Oklahoma, he got a job as a drum major in a marching band. He was, at last, in

show business, and he was soon a member of the Miller Brothers 101 Real Wild

West Show, an operation in the tradition of Buffalo Bill’s traveling

extravaganza. From then on, it was all showmanship.

In

comic books, the Mix legend was perpetuated by Fawcett in Tom Mix Western,

1947-1953. It was a memorable performance, arguably the best work ever by Carl

Pfuefer teamed with inker John Jordan— lively, energetic action on every page.

And Pfuefer could draw Tom Mix to look exactly like Tom Mix.

The

other famous Western fraud was a cowboy artist like Russell. Neither ever made

it to comic books, but Will James (1892-1942) wrote stories, books of

them--which he illustrated himself. He wrote the books in a made-up lingo that

suggested, with bad grammar and country syntax, that the author was a somewhat

less-than-educated person— like a real cowboy, in other words. But James’

jargon was as phony as his own personal history.

One

of his most celebrated prose works is The Lone Cowboy, which James

asserts is his “life story,” the story of the youth and maturation of a cowboy

artist. According to the book, James was born in a covered wagon in Montana.

He was orphaned at an early age and subsequently raised by a French-Canadian

trapper named Bopy, with whom he wandered the Judith Basin in Montana, learning

how to survive and how to draw.

I

read this tome as a youth. Avidly. I was growing up in Denver, a West

somewhat different than that of the Lone Cowboy’s, admittedly; but I’d just

figuratively apprenticed myself to Dick Sebald, who was producing a quaint

weekly masterpiece of cartoonery called Sage, Sand, and Salt that

humorously retailed the amusing “doin’s”of a ordinary cowpoke named Balin’ Wire

Bill on his one-steer spread at Broken Spoke, Wyo. (“Apprenticeships” among

cartoonists entail nothing more exotic than copying religiously the work of an

admired cartoonist.)

Will

James and Dick Sebald and Balin’ Wire Bill and me—we all seemed pointed in the

same direction, and I devoured the paragraphs in The Lone Cowboy about

James’ artistic aspirations and exercises. Wonderful stuff.

All

invented. Well, the French-Canadian trapper and orphan stuff anyhow. Will

James was actually born in Canada and raised in a French-speaking household in

and around Montreal. He fell in love with cowboying at an early age and left

home, with his parents’ blessing, at the age of fifteen (after completing an

education) to spend three years in western Canada, learning the cowboy trade

and how to speak English. At eighteen (or about 1910), he crossed the border

to the U.S., realizing that only in the American West could he be a real

cowboy.

Beginning

with Chapter Nine, The Lone Cowboy more closely approximates James’

actual life. He bummed around the West for the next decade, rustled some

cattle, spent a year or so in jail for it, and drew pictures a lot. He also

told stories, and when he wrote down the story of his life with a horse named

Smoky and submitted it to a magazine, his career as an artist-author took off.

He

didn’t survive fame well: he drank himself to death by the age of fifty. We

probably wouldn’t ever have found out about his fraudulent past if he hadn’t

left money in his will to Ernest Dufault in Ontario, Canada— “the sole heir and

survivor of my dear old friend, Old Beaupre [Bopy], who raised me and acted as

a father to me.”

This

was a mistake: James probably meant to write “Auguste Dufault,” the name of his

brother. Will James was himself Ernest Dufault. And in tracking down the

beneficiary of the Will James’ legacy, the diligent authorities found Auguste

who told them about his famous artist-author brother, Will James.

Despite

all the make-believe, Tom Mix and Will James had actual accomplishments to

point to. Mix’s daring as his own stunt man probably equaled anything he

claimed to have done as a soldier of fortune. And he created, as I said, the

Hollywood cowboy hero, which did more to establish the Western as our mythology

than any other narrative genre.

Meanwhile,

Will James, in fabricating his own past, created one of the most luminous

portraits of the West and of living the great adventure in it that our

literature affords. And his pictures of cowboys and, particularly, of horses

in the Old West reek of authenticity. Because most of his artwork illustrated

his books, he left far fewer color paintings than did that other painter of the

West, Charlie Russell, but the genuineness of James’ work is in the same

league.

But

to speak of fraud when discussing the Western is to describe the American

mythology, after all. As I said earlier, the lone champion of that myth is a

piece of fiction, a literary construct, as much make-believe as Will James or

Tom Mix. But myths are like that— engaging, absorbing, and their truth, like

Will James’ and Tom Mix’s, is in the make-believe.

And

what of the American mythology now that the comic book Western has all but

disappeared? If it hasn’t become transparently obvious that the hero of the

Western myth is perpetuated today in the vigilante adventures of the four-color

longjohn legions, you’ll need to browse a chapter or two in a couple of my

books, The Art of the Comic Book and the latest, Insider Histories of

Cartooning—both advertised and sold elsewhere on this website; just return

to the main page, click on Enter Here, then scroll down until you see pictures

of the books’ covers.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |