REMEMBERING PLAYBOY & HEF

In Memorium

Every time I saw Hugh Hefner with a pipe in his hand, I knew he was a fake. The pipe created a phoney pose. He didn’t really smoke a pipe. Except for photographers. And even then, the pipe was seldom in his mouth, being smoked. It was usually in his hand where it would enhance his image as a freedom-loving dapper hedonist-about-town who smoked a pipe.

It was just too obvious that he was holding the pipe as a prop.

But

when I found out he gave up the pipe in 1985, I had to pause. Maybe he was a

pipe-smoker after all.

It wasn’t the only time I’ve had to adjust my opinion of Hefner. Most recently in the wake of an A&E docuseries, “Playboy Secrets” about the scabarous goings-on at the Playboy Mansion. I knew he kept a harem of a half-dozen or so private playmates at the Mansion, but I didn’t realize (because until “Playboy Secrets” I didn’t know) the extent to which he abused these women. I thought they were all consenting adults. Well, maybe—eventually adults. For some of them. But many were teenagers when Hef first locked onto them, and he exploited them for his own sexual pleasure.

So, as you see, I have scarcely been right about him enough to claim special insight.

Hugh

Hefner, founder of Playboy magazine, died in September 2017, and he was

editing the magazine right up to the end. Almost. The magazine died with the

March 2020 issue, two-and-a-half years after Hef’s death. It disappeared

without any public notice whatsoever. None that I saw. And that may explain why

I didn’t know it had died until two years later, just last week. By then, it

was history.

But regardless we’ll conduct a memorial service for the magazine here at Rancid Raves. I’ll cull some of the more-or-less agreed-upon information from a few of my previous attempts at Hefner biography and Playboy history. Plus a few fresh seasonings and spices (it is Playboy after all).

The history of Playboy begins in the summer of 1953. Or maybe in the winter of 1948. It was then, while enrolled at the University of Illinois, that Hef (the nickname he adopted while in high school in order to seem “cooler” than he was) first tasted magazine editorship with the kind of magazine he might’ve wanted to produce. Perhaps it was that editorial experience that suggested his future career.

With an IQ of 152, Hef graduated in two-and-a-half years (in February 1949) with a BA in psychology and a double minor in creative writing and arts. While enrolled at the U of I, he edited an issue of an off-campus humor magazine, Shaft, which, under Hef’s superintending eye, was an incipient Playboy.

The cover of that issue is not, as it usually was, a cartoon: instead, it is a photograph of a pretty girl—a girl modestly attired in a dress that bares her shoulders and back but is gathered in front just below her chin. No decolletage whatsoever.

|

|

She was, nonetheless, a perfect incarnation of “the girl next door” to come. About this early manifestation of a Playmate, Hef writes: "No movie star this, just an average, run-of-the-mill coed at dear old Illinois." This discreet phantom of Hefner's decorous heavy breathing would, in five years, be reincarnated, but this time, without raiment.

The magazine also featured full-page cartoons (in addition to the usual quarter-page variety found in most “general interest” magazines of the day).

The other remarkable thing about the only issue of the Shaft that Hef edited is that his editorial reveals his thinking on sexual matters already firmly in place—or, as you might say, his arrested development fully arrested. And in that, he was in perfect step with the rest of American manhood. Here's the whole editorial:

"Sort of a personal retaliation, my becoming editor of Shaft. The first time this journalistic abortion printed my name, they misspelled it. [He was listed in the June 1947 issue as "Heff," with two ef's.]

"The other day I was thumbing thru what may be 1948's most important book— Sexual Behavior in the Human Male by Alfred C. Kinsey, professor of zoology at Indiana University. This 700-page volume is the first thorough examination of American sex behavior and attitudes—the result of nine years of study, during which Dr. Kinsey and his associates interviewed nearly 12,000 men. After considering this evidence, '48 magazine concluded: If American law were rigidly enforced, ninety-five percent of all men and boys would be jailed as sex offenders.

"What about college men? Well, as a group, they are decidedly less promiscuous than the average of the male population. They do indulge in more experiences with the girl they intend

marrying, however. I don't know how you're making out, but my girl doesn't believe in surveys. [Millie Williams, his highschool girlfriend who was attending the University of Illinois, did not, according to one of Hefner’s biographers, succumb to Hef's lustful pleading until the ensuing summer, when the couple repaired to a motel in Danville thirty-five miles away.]

"We're waiting impatiently for the female study.

"On a serious note—Dr. Kinsey's book disturbs me. Not because I consider the American people overly immoral, but this study makes obvious the lack of understanding and realistic thinking that have gone into the formation of our sex standards and laws. Our moral pretenses, our hypocrisy on matters of sex, have led to incalculable frustration, delinquency and unhappiness. One of these days, I'm going to do an editorial on the subject, but for now, we'll leave it to the Soc. classes and bull sessions."

Hefner would devote most of the rest of his life to the "editorial on the subject."

From its humble beginning as a sort of rogue version of Shaft, Playboy would grow until it was the ninth greatest circulation magazine in the United States.

HEF STARTED OUT

IN LIFE thinking he was a cartoonist. He began drawing books of

autobiographical cartoons while in high school and continued with autobiographical

scrapbooks for much of the rest of his life. But when he failed as a

cartoonist, he produced one of the world’s great magazines instead. While in

the planning stages, Hefner called the magazine Stag Party; but he had

to give up that name when another magazine, Stag, threatened legal

action.

Playboy was launched from Chicago in November 1953. Hefner raised $8,000 from 45 investors (including a $1,000 loan from his mother).

The first issue was undated because, St. Wikipedia claims, Hefner wasn’t confident that there’d be a second issue. Not true: it was undated so it would stay for sale on the newssstands as long as possible. In those days, the distributors of periodicals removed magazines from the newsstands once the date on the cover was passed. With no date, Playboy would stay longer. As it turns out, that was a needless precaution: the first issue sold out in mere weeks—due, chiefly, to the presence of a famous photograph of Marilyn Monroe stretched out naked on a red velvet cloth.

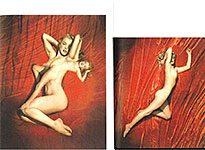

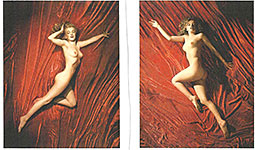

She was the first centerfold, the first Playmate. The photo featured one of several of her nude poses for a calendar—not for Playboy— that had been shot in late May1949 by photographer Tom Kelley in his Hollywood studio. He took twenty 8x10-inch portraits, plus a couple rolls of smaller size. Five of the portraits, all of which can be found on the Web in various places or in Tom Kelley’s Studio, a 300 10x11-inch page tome published in 2014 featuring female nudes by Kelley.

|

|

|

|

Marilyn (who famously replied to a “spectacularly unobservant” reporter who asked what she had on, said, “The radio”) was then a struggling actress desperate to pay the rent. The presence during the shoot of Kelley’s wife, acting as his assistant, rescued the adventure from any salacious interpretation.

By the time Marilyn appeared naked on a 1952 calendar, she was a starlet on the cusp of fame; the nude picture shoved her over into celebrity. Although it is sometimes claimed that Hefner chose what he deemed the “sexiest” photo, “previously unused,” the centerfold in fact pictured the calendar photo, which was then circulating on calendars all over the place. So Hef’s referencing the already-famous nude calendar Marilyn in promoting the first issue of Playboy cinched the magazine’s success: it sold its 53,991 copies at 50 cents a copy in just weeks.

Playboy’s publisher, instantly famous, would soon become a millionaire; after five years, the magazine’s annual profit was $4 million and its rabbit logo was recognized around the world.

Hef ran the magazine and then the business empire largely from his bedroom, working on a round bed that revolved and vibrated. At first he was reclusive and frenetic, powered past dawn by amphetamines and Pepsi-Cola.

In the early days when he had a bedroom constructed to adjoin his office at the magazine’s Chicago headquarters, he was known to work 40 hours straight on the magazine, choosing just the right pose for the Playmate, tinkering with cartoon captions, and so on. In later years, even after giving up dexedrine, he was still frenetic, and still fiercely attentive to his magazine.

Playboy's enduring mascot, a stylized silhouette of a rabbit wearing a tuxedo collar and

bow tie, didn’t appear until the magazine’s second issue. It was created by Playboy art director Art Paul as an endnote, a symbol at the end of an article to

signal its conclusion. But it was quickly adopted as the official logo and has

appeared on the magazine’s cover, often mischievously hidden, ever since.

Hefner said he chose the rabbit for its "humorous sexual connotation," and because the image was "frisky and playful.”

In an interview, Hefner explained his choice of a rabbit as Playboy's logo to the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci:

“The rabbit, the bunny, in America has a sexual meaning,” he said, “—and I chose it because it's a fresh animal, shy, vivacious, jumping. Sexy. First it smells you then it escapes, then it comes back, and you feel like caressing it, playing with it. A girl resembles a bunny. Joyful, joking. Consider the girl we made popular: the Playmate of the Month. She is never sophisticated, a girl you cannot really have. She is a young, healthy, simple girl— the girl next door ... we are not interested in the mysterious, difficult woman, the femme fatale, who wears elegant underwear, with lace, and she is sad, and somehow mentally filthy. The Playboy girl has no lace, no underwear, she is naked, well washed with soap and water, and she is happy.”

ALMOST UNIVERSALLY ACKNOWLEDGED for playing a significant role in the sexual revolution that swamped the country in the 1950s and 1960s, Playboy is one of the world's best-known brands, having grown into Playboy Enterprises, Inc. (PEI), with a presence in nearly every medium. In addition to the flagship magazine in the United States, special nation-specific versions of Playboy were published worldwide

The magazine has a long history of publishing short stories by distinguished writers like Arthur C. Clarke, Ian Fleming, Vladimir Nabokov, Saul Bellow, Chuck Palahniuk, P. G. Wodehouse, Roald Dahl, Haruki Murakami, and Margaret Atwood. A list like this was part of Hefner’s strategy: notable names gave the magazine literary stature.

Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 was published in 1953 and serialized in the March, April and May 1954 issues of the magazine.

In yet another maneuver to give the magazine cultural heft, Playboy featured extensive (usually several thousand-word) interviews of public figures— artists, architects, economists, composers, conductors, film directors, journalists, novelists, playwrights, religious figures, politicians, athletes, and race car drivers.

Writer Alex Haley was the first interviewer and continued to serve in that role on a few occasions. One of his interviews was with Martin Luther King Jr.; he also interviewed Malcolm X and American Nazi Party founder George Lincoln Rockwell (who was astonished when he learned Haley was Black; Rockwell kept a pistol on the table in front of him throughout the interview).

For the November 1976 issue, which was published on the eve of the Presidential Election, the magazine published an interview with then-presidential candidate Jimmy Carter, whereupon he famously stated, “I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times”—a sort of backhanded endorsement of the centerfold.

David Sheff's interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono appeared in the January 1981 issue, which was on newsstands at the time of Lennon's murder; the interview was later published in book format.

The magazine generally reflects a liberal editorial stance, although it often interviews conservative celebrities.

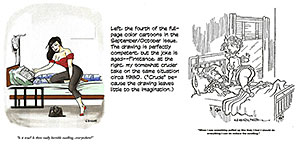

As a wannabe cartoonist, Hefner valued cartoons and gave them ample display in the magazine with a full-page full-color presence from the very beginning. Playboy became a showcase for the painterly appearance of cartoons by such cartoonists as Dink Siegel, ffolkes, Don Madden, R. Taylor, Buck Brown, Phil Interlandi, Rowland B. Wilson, John Dempsey, Erich Sokol and, later, Eldon Dedini, Roy Raymonde, Doug Sneyd, and Dean Yeagle—not to mention black-and-white masters like Gahan Wilson, Jules Feiffer, Shel Silverstein, and the rest of the stable of regulars that Hefner laboriously assembled over the years. INSERT

|

|

|

|

In

my view, Hef first achieved his vision for cartoons in the luminous watercolors

of Jack Cole, who’d made his name and found his fame in comicbooks with

his Plastic Man creation. Cole's Playboy cartoons did not at all

resemble Plastic Man. Emphatically not at all. His cartoons started to appear

in the fifth issue of Playboy, and his painterly excellence established

a standard for Playboy full-color cartoons.

Cole, as every cartoon fanaddict knows, killed himself in the summer of 1958, but by then, his cartoons with their fleshy, zaftig cuties had set the mold. Not that Playboy cartoonists imitate Cole: they most emphatically do not. But they approach their work with an artist's color palette tools, not a cartoonist's pen and ink, and in that, they follow in Cole's footsteps.

By the time Playboy had been published for a decade, it was one of the last redoubts of single-panel gag cartooning in America. The New Yorker is the other. All the other great magazine cartoon venues— The Saturday Evening Post, Look, Collier's, even True—had expired, leaving legions of magazine gag cartoonists scraping eraser crumbs off their drawingboards for sustenance. Hefner was not among them. And he was probably living on caviar as well as Pepsis, his famous drink of choice, not eraser crumbs.

MY EXPERIENCE with Playboy is almost as long as Hugh Hefner’s but not nearly as rewarding either financially or recreationally. My first encounter with the magazine was in Jerry’s, a downtown Denver newsstand, in approximately June 1955, when Hef’s revolution in American sexual mores had been going on for only about 18 months. My friend Gary had dragged me, willingly, into Jerry’s to show me this new publishing phenomenon.

“Here,” he said, plucking the August issue off the rack and thrusting it into my hands, “—what do you think of this?”

At the age of approximately eighteen, I was not ready to do much thinking in the vicinity of Playboy. And I didn’t. Emotion was in complete control. Fear, mainly. After thumbing furtively through a few pages of the magazine, I quickly put it back on the rack, and Gary and I left Jerry’s as fast as we could, hoping to escape before we attracted the attention of the proprietor, who, we imagined, would doubtless disapprove of two adolescents giving their hormones a rush in public.

Despite

the incomprehensible brevity of my introduction, I remember vividly the cover

of the first issue of Playboy I ever saw, described, in The Playboy

Book as having “achieved notoriety when a strategically placed strand of

seaweed mysteriously slipped out of place sometime during the printing

process.” Nearby is the incriminating evidence, a copy of the salacious cover

itself.

That fall, by then a freshman in college and free of any remnant of adult supervision whatsoever, I purchased my next issue of Playboy and was therefore able to inspect it at somewhat greater leisure. In those days, Playboy was widely celebrated as a “science-fiction magazine”: the pages devoted to hi-fi phonograph record players and other technological advances for the modern bachelor apartment comprised the “science” section; the rest of the magazine, went the quip, was “fiction.”

Apart from rejoicing in the generous display of barenekkidwimmin in the “fiction” department, I was impressed with the cartoons. Lots of them, and most in full color, like paintings. As a neophyte cartoonist, I was smitten. Admiring the cartoons became almost as consuming a preoccupation with every new issue of Playboy as admiring centerfolds and other manifestations of nakedness. And in the months that Jack Cole was allotted several pages in order to treat some subject in depth, the airbrushed photos of female embonpoint took second place on my agenda. Well, almost second place.

My next notable experience with Playboy was in the fall of 1958, when, as a campus cartoonist attending a college journalism convention in Chicago, I had played hooky one afternoon to take some of my cartoons to the magazine's headquarters, then in Chicago at 232 East Ohio Street.

The building was one of those shotgun structures—narrow across the front but burrowing deep into the lot behind. I walked into the first floor reception area, stated my business to a striking-looking blonde lady at the desk, and was directed to an elevator that would take me to the fourth floor. The elevator stopped at the second and third floors, and each time the door opened, I was treated to another blonde vision at a reception desk.

When I told the blonde at the fourth floor desk my errand, she summoned someone by phone. Another blonde appeared, looked over my drawings, and then asked me to wait. I did. She returned shortly and escorted me to the office of Jerry White, one of two assistants to art director Arthur Paul.

White,

dark-haired, bearded, looked at my drawings, made sympathetic sounds, and told

me to keep at it because they were looking for younger cartoonists who could

bring to the magazine a somewhat less jaded view than might be found in the

work of such mature cartoonists as Gardner Rea, who was then in his

mid-sixties. I remember that White mentioned Rea specifically.

White,

dark-haired, bearded, looked at my drawings, made sympathetic sounds, and told

me to keep at it because they were looking for younger cartoonists who could

bring to the magazine a somewhat less jaded view than might be found in the

work of such mature cartoonists as Gardner Rea, who was then in his

mid-sixties. I remember that White mentioned Rea specifically.

The cartoon below Rea’s, just here, at elbow of your eye, is one of the cartoons I had in my portfolio. This is a copy. The original, which I’ve lost track of years ago, was drawn in brown pencil, enhanced with brush-applied black ink for some of the more crucial delineation. I thought it arty enough for Playboy. White didn’t agree. I left with my portfolio intact, my sales record unblemished.

YEARS LATER, I MET MICHELLE URRY, the magazine’s esteemed cartoon editor, at Playboy’s New York offices. I wasn’t trying to sell her one of my cartoons (although I had been submitting my work to Playboy for some time by then); I was interviewing her for Jud Hurd’s quarterly journal, Carto

onist PROfiles. The interview almost didn’t happen.

Hurd had set up the interview to coincide with one of my periodic visits to New York. But the interview was very nearly cancelled when, a couple weeks before the visit, I was making final arrangements with Urry’s secretary and remarked innocently about how the article would serve to tell potential contributors what they needed to know in order to contribute to Playboy.

Next thing I knew, Urry was on the phone, cancelling the interview because, she explained, the last thing she wanted was more unsolicited contributions being sent in from multitudes of unknown persons.

Oooops! All at once, I saw my “historic” interview with Playboy’s cartoon editor whisking away, out the door, out of sight. Thinking fast—not my customary mode—I said:

“Well, okay—instead of encouraging submissions, we'll DIScourage them.”

On that basis, she consented, somewhat reluctantly I thought, to the interview. I also said I’d let her read the whole article when I finished, and she could make corrections, additions or subtractions, as she chose.

She then imposed another condition: once I'd finished with the tape of the interview, I was to send it to her. She wanted the physical evidence, the only irrefutable evidence of our encounter—her words in her own voice. Cloak and dagger stuff. So what would prevent me from having a copy made of the tape for my own lascivious purposes later? Dunno. But she wanted the tape.

During the interview, Urry said, among many other things, that she had an “inordinately dirty mind,” and she said it by way of explaining a successful life-long career as cartoon editor of a magazine renowned for publishing the nation’s best naughty cartoons. But she knew, as did the cartoonists she worked with, that the secret of her success was not that she enjoyed a so-called dirty joke. Her success depended upon more than that.

When she died at her home in Manhattan on October 15, 2006, she had been Playboy’s cartoon editor for more than 34 years. You don’t survive in the hothouse of cartoonist egos for three-and-a-half decades just because you like jokes about sex. It helps, but it isn’t the whole reason for survival.

She lasted at the job because she did very well what Hefner needed her to do: she screened all cartoon submissions, more than a thousand a month she said, picking a dozen or so of what she thought were the best for Hefner to choose from, and she kept track of cartoonists, handling correspondence with them and coaching new talent and nurturing the old hands. She was both administrator and manager.

And cheerleader. Jules Feiffer had it exactly right when he told Douglas Martin at the New York Times that Michelle Urry was “mother superior to cartoonists.” She famously held poker parties for cartoonists at her loft and Christmas parties for them at Playboy’s New York offices. She liked cartoonists, and she cared for them.

When I had my fling at magazine cartooning in the late 1970s, I was surprised, pleasantly, to learn that the cartoon editor of the nation’s preeminent men’s magazine was a woman. In a publication whose most visible raison d’etre was affording male readers an unimpeded view of naked wimmin in the nude, it was refreshing to find that a major editorial position was held by a woman. It was symbolic: it meant women liked sex, too.

It was more than symbolic. We don’t know if Urry liked sex any more (or less) than the rest of us, but we do know that she enjoyed laughing about it, and that, undoubtedly, influenced the attitude of Playboy’s cartoons. The girls in Playboy’s cartoons are invariably depicted as having fun with their sexual cohorts. Playboy cartoons do not leer at sexy women in the manner of Army Laughs and an armada of Humorama digest-sized magazines in the 1950s and before.

The women in Playboy cartoons are not sex objects: they are sexual partners who delight in a romp in the hay as much as the men they romp with. It’s the attitude, a very modern attitude, and Urry fostered it. She may not have made the final selection—that, she was always quick to say, was Hef’s role—but she culled out the good stuff for him, and in the good stuff, women enjoyed sex. Sex was fun for everyone.

As I sent cartoons around to other men’s magazines, I learned that many of the cartoon editors were women. At first, I was delighted by this seeming sea change in American attitudes about sex. And then I realized that the sea wasn’t changing at all. It was the same old sexist economic tide, running, as always, against women. And in this case, it also attested to the nearly absent esteem for cartoons at the low-budget imitators of Playboy. Women would work for less money than men, and since picking cartoons wasn’t all that important in magazines of salacious gynecological color photographs, women, usually the secretary to the editor, got to pick the cartoons—or screened them for their boss’s final selection.

I don’t know about Urry’s salary, but I suspect it was a good deal better than the average secretary’s: Hefner, after all, was a frustrated cartoonist—and, by all accounts, one of the best cartoon editors, capable of giving insightful and comedically crucial advice to cartoonists and demanding that extra chuckle—and he surely held cartoons and his magazine’s cartoonists in the highest regard. He would scarcely scrimp on his cartoon screener’s pay. Urry’s route to her exalted position, however, began at a secretary’s desk.

She was born on December 28, 1939, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Her father was a clothing manufacturer, and Michelle, even after majoring in English at the University of California, set her sights on being a dress designer, opening her own shop in Los Angeles. She left there to try New York but didn’t like it and wound up in Chicago in 1964, taking her portfolio to Playboy, where, for a time, she did secretarial chores until she protested and got a new assignment— answering phones at Chicago’s Playboy Mansion.

Then when she went to a party at the Mansion and made her boss laugh, she was invited to help with cartoon submissions. The job, she said in a 1971 interview in the National Observer, came with “some onus”: her predecessor had been one of Hef’s girlfriends and gossip was rampant. But Urry demonstrated a surpassing knack at her task.

“The fact that I brought to it an inordinately dirty mind was my own doing,” she said, “—I mean, I don’t think he expected that kind of bonus.”

However unexpected, Urry’s attitudes and her efficiency yielded a life-time career. Cartoonist Eldon Dedini told me in late 2004 that Urry had told him that she was going to retire; a year later, Dedini said she’d told him Hefner talked her out of it. And so she kept on until she died, in one of those supreme ironies in which fate sometimes deals, of ocular melanoma, a cancer of the eye. That a person who made a living looking at cartoon art would die of an eye ailment is ineffably numinous.

Some would see it as punishment for a lifetime of looking at naked bodies engaged in sexual rambunctions; others, like me, would say she simply wore her eye out in her devotion to the job and the craft—the art—of cartooning, a noble conclusion to a praise-worthy dedication. Her legacy, so to speak, can be found in the cartoons of Playboy, one of the last great venues for gag cartooning, the haiku-like art of eliciting laughter with a single drawing and a revealing caption.

Whatever the reason, Urry wanted the tape of our conversation. And after I’d transcribed it, I sent it to her. In reviewing the article before publication, Urry had tinkered with a few word choices, but made no substantive changes. I’d already cleaned up the syntax, removing sentence fragments and false starts. A few weeks after our visit, she wrote me: “I appreciate the tender handling and the ease and elegance of your interview style.”

Which I quote here by way of suggesting that the unedited transcript, although fraught with sentence fragments, contains nothing she would object to.

By the time of our interview, Urry was one of the nation's longest-tenured cartoon editors. She had watched the field closely for years and had much to say that is probably still of interest to magazine gag cartoonists as well as students of the medium. Her office in Playboy’s New York headquarters was around the corner and down the hall from a lofty two-story reception vault in which spiraling staircases aspired to offices on the second level.

Urry’s sanctum was far less imposing: it was arranged for informality and comfort. No desk. Just a small round table in the center of the room, bookshelves on the wall to the left of the entry, a couch against the opposite wall. Piles of paper and cartoonists' submissions on the table and the couch. I took a chair next to the couch; Urry sat on the couch. She smiled.

We talked about how she wound up, a dress designer, as cartoon editor at a men’s magazine.

She’d left New York and was in Chicago.

“So then I needed a new job,” she said. “There was nothing in the design field. Somebody said, Hefner's got Playboy— you've got a portfolio. Why not try there? So I did. And I said, I'd like to change my career. I'm as good verbally as I am visually. Put me someplace and I'll learn. So they put me in a department where I composed letters to would-be Bunnies— all those fourteen-year-olds who want to run away from home and become a Bunny. And I did that for a rather long time, campaigning all the while— because they said if I did that for awhile, they'd find me job as an assistant editor or something.

“Then I met Hef, and I made him laugh, and at some point, he said, I'm going to apprentice that girl. I would never have dared ask him for a job. He was the only person I knew that you didn't ask for a job.

“And he had no way of knowing exactly how much of a cartooning enthusiast I was. I had the biggest collection of comic books of any girl, I think, in a radius of fifty blocks in my hometown.

“It never occurred to me that I could actually get a job— I mean, who thinks they're going to get a job as a cartoon editor? What a wonderful job. After doing it for many years, I still feel that I think it's kind of the most interesting— it's hard for me to believe that I'm still a fan. And I am. I'm still fresh and open to new work. I look forward to opening stuff on the off-chance that there'll be some brilliant new talent there. And I'll giggle. I really do. I don't know how people keep on doing it over and over and over again. But cartoonists are special. They aren't like other people. Oh, sure— they come in all sizes, shapes, and breeds. But gag cartoonists particularly are a special breed, and they're dying out. I mean, it's not a good way to make a living any more.”

I agreed, and I quoted Lee Lorenz, then cartoon editor of The New Yorker, who had said recently that “gag cartooning has been melting since the early sixties. People are now clinging to what used to be a glacier and is now about the size of an ice cube.”

“Well, he ought to know,” Urry said, “—he’s a gag cartoonist.”

“And he’s dead right,” I said. “You look around. There aren't many places for gag cartoonists to sell to any more.”

“There aren't that many magazines publishing,” Urry said. “And the people that do publish cartoons, all have ideas about what they want, and that lets out a lot of people. But the really smart guys saw it coming a long time ago and started branching off into children's books, into teaching, into doing—.”

Into doing a lot of other things with their pencils.

All the more reason to rejoice here and enjoy some more of the brilliant work of Playboy cartoonists over the last few years before the no-nudes infestation destroyed Playboy’s cartoon niche. INSERT PlayboyToons5 through PlayboyToons16 HERE; THEN DELETE THESE CAPITAL LETTERS.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE PLAYBOY KEY CLUBS started in early 1960 at 116 E. Walton Street in downtown Chicago. It may have been prompted into existence by Playboy’s Penthouse, a late-night variety/talk television show hosted by the wiry, intense Hefner, who, pipe perpetually in hand, welcomed singers and musicians and comedians and all sorts of show business personalities into informal conversation and performance. The set recreated his Mansion, rich in sybaritic amusements, where he greeted entertainers like Tony Bennett, Ella Fitzgerald, Dick Gregory and Nat King Cole, and intellectuals and writers like Max Lerner, Norman Mailer and Alex Haley, while bunches of glamorous young women milled around. It ran for two seasons, starting in October 1959.

The most celebrated aspect of the Playboy Clubs were the Bunnies—cocktail waitresses wearing streamlined but skimpy costumes that showed off bosoms and legs. The uniform included rabbit ears as a headdress and a cotton tail on the rump.

Famous as the fuzzy tail was, it was the highly regulated life of a Bunny that attracted attention. The Bunny costume was designed for its sex appeal, but sex went nowhere in a Playboy Club: the Bunnies were not permitted to date any of the customers. Some of the Bunnies, however, wound up as Playmates.

Playboy Clubs spread across the country rapidly through the sixties. Eventually, there were 23 of them in the U.S., plus a few in foreign climes, starting in London and Jamaica.

By the 1980s, the Clubs had run their course and began to close. They were defunct by 1991 but made a short comeback in the early 2000s.

CARTOONS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN IMPORTANT in Playboy. In introducing one of the magazine’s several book celebrations of its fiftieth anniversary, Playboy 50 Years: The Cartoons, Hefner, the magazine's septuagenarian founder (still appearing in photographs, as always, grinning like the cat who's munched a particularly bountiful canary, the grin, in recent years, looking suspiciously frozen by Botox), says: "I once commented that without the centerfold, Playboy would be just another literary magazine. The same can be said for the cartoons. Playboy's visual humor has helped to define the magazine." I agree.

No one, thumbing his way through any issue of Playboy, could doubt that its cartoons have done much to establish the essential character of the magazine. “Playboy wouldn’t be Playboy without cartoons,” the magazine proclaimed. “Great gusty quantities of full-color, fulll-page cartoons fill the magazine every month, to say nothing of frequent multipage cartoon spreads and the less flamboyant but no less funny black-and-white chucklers that pepper the back pages. These cartoons are created by the most gifted coterie of dotty draftsmen ever assembled under one aegis.”

From the start, Hefner set out to recruit a stable of cartoonists whose work would be distinctive, unique, in magazine cartooning and would appear almost exclusively in his magazine. For this reason, he shunned one of that day's most well-known cartooners of the feminine form— Michael Berry. Berry's flaxine-haired statuesque but vacuous beauties were everywhere in magazines, advertisements as well as cartoons. And Hef wanted a new "look," something not already on display everywhere. Berry, alas, was everywhere.

|

|

|

For the first twenty years, Playboy grew steadily in circulation. In 1971, Playboy had a circulation rate base of seven million, which was its high point. The best-selling individual issue was the November 1972 edition, which sold 7,161,561 copies. It was said then that one-quarter of all American college men were buying or subscribing to the magazine every month.

By 1975, however, its circulation had begun to taper off and decline. Midway through the decade, its average circulation was 5.6 million; by 1981 it was 5.2 million, and by 1982 down to 4.9 million. Its decline continued in later decades, and reached about 800,000 copies per issue in late 2015, and 400,000 copies by December 2017.

After reaching its peak in the 1970s, Playboy saw a decline in circulation and cultural relevance due to competition in the field it founded—first from Penthouse, then from Oui (which was published by Playboy as a spin-off) and Gallery in the 1970s; later from pornographic videos; and more recently from lad mags such as Maxim, FHM, and Stuff. In response, Playboy attempted to re-assert its hold on the 18- to 35-year-old male demographic through slight changes to content and focusing on issues and personalities more appropriate to its audience—such as hip-hop artists being featured in the Playboy Interview.

But these adjustments were underwhelmingly successful, and in June 2009, Playboy reduced its publication schedule to 11 issues per year by combining the July and August issues. Six months later, in December 2009—still seeking to improve the bottom line by reducing the expense of monthly publication— the schedule was reduced to 10 issues per year, with a combined January/February issue.

Then in October 2015 came the most startling change: Playboy announced the magazine would no longer feature full-frontal feminine nudity beginning with the March 2016 issue.

Company CEO Scott Flanders acknowledged the magazine's inability to compete with freely available Internet pornography and nudity. Said he: "You're now one click away from every sex act imaginable for free. And so it's just passé at this juncture.”

Hefner agreed with the decision.

“This is what I always intended Playboy magazine to look like,” he said, no doubt grinning his denial.

Some argued that the motivation for the decision to eliminate nudity in the magazine was to give Playboy Licensing a less inappropriate image in India and China, where the brand is a popular item on apparel and thus generates significant revenue.

The new approach to nudity was but one of several changes at the magazine: the whole thing was redesigned.

The new Playboy featured short 1-3 page articles, many of them, interviews, with headlines of bold black lettering. The page size was increased, and white space—lots of it—was the dominant feel of the redesign. The first issue of the new design had a 7-page interview with Rachel Maddow, accompanied by a giant, full-page black-and-white close-up of her grimacing visage. Karl Ove Knausgaard in an article entitled “The Morning After” describes in exhaustive detail his first experience at masturbation.

Most

of the text articles clustered at the front of the magazine. Towards the back,

we encountered several pages of photographs of non-nude females with their

clothes off. The redesigned Playboy still featured a Playmate of the

Month and other pictures of women, and some of the women would be naked, but

they would be wholesomely wrapped or artfully posed to prevent readers from

seeing nipples or vaginas. In subsequent issues, the number of pages featuring

non-nudes increased.

Other changes to the magazine included ending the popular Party Jokes section and the cartoons that appeared throughout the magazine. The redesign had eliminated the use of jump copy (articles continuing on non-consecutive pages), which in turn eliminated most of the space for the quarter-page black-and-white cartoons. Why the full-page color cartoons needed to be eliminated too is something of a mystery, but they were gone. Hefner reportedly resisted dropping the cartoons more than losing the nudity, but ultimately obliged.

Playboy's plan was to market itself as a competitor to Vanity Fair, as opposed to more traditional competitors GQ and Maxim.

But it didn’t work. A year later, Playboy announced (in February 2017) that dropping the nudity had been a mistake. Barenekkidwimmin with nipples and vaginas made a come-back in the March/April 2017 issue. And, furthermore, the magazine re-established some of its franchises, including the Playboy Philosophy and Party Jokes. But it dropped the subtitle “Entertainment for Men” on the cover inasmuch as gender roles have evolved.

And somewhere along the line, full-page color drawings impersonating cartoons began appearing on more pages in the magazine. But they scarcely restored the traditional Playboy cartoon. Instead, they had a modern “contemporary look.” No art. Just color, flat color of no distinction.

THE ART OF THESE “NEW” PLAYBOY CARTOONS, compared to the graphic tradition Hef had so carefully established and maintained for over sixty years, was pitifully lame. In place of the exuberantly water-colored imagery of yore we had only outline drawings, unimaginatively colored. Jack Cole, whose water-colors had established the magazine’s cartoon tradition, was doubtless turning over in his grave. Ditto Hef.

And then, as if to undercut its new cartoons, the mag began to offer a couple pages at the end of each issue that reprinted some of the old wonderful stuff. Classic Cartoons. Aren't they afraid someone will notice in comparison how bad the current gaggle is? Take a look.

|

|

|

The first thing you notice is the stark simplicity of the art in the new cartoons. No artistic ruffles and flourishes. Just simple line drawings. While competent draftsmanship is evident in these new cartoons, there’s none of the visual excitement of the good old days.

Nishant Choksi’s naked man reading a book is a full-page cartoon. All of the new cartoons are full-pagers. What a waste of space. None of the pictures are complex enough—or graphically embellished enough— or even pictorially interesting enough—to require all that display space.

Women appear in some of the cartoons, but they aren’t the voluptuous, sex-loving women of yesteryear. These are merely the female of the species.

Finally,

the jokes themselves are pretty weak tea. Playboy’s cartoons used to be

robust celebrations of sex and sex appeal. The new jokes are just clever.

Clever but not at all manly in the chest-thumping sexual bravado manner of

yesteryear. And some of the cleverness is fairly threadbare stuff, tired old

ploys rather than joyful celebrations.

Nicholas Gurewitch was aboard from the very beginning of the new Playboy, if I recall aright. I think he’s had a so-called “cartoon” in every issue of the de-nuded Playboy and its successor, the re-nuded Playboy. Clever stuff, usually, but pretty far from the traditional Playboy cartoon. Gurewitch is pretty clearly THE Playboy cartoonist of this iteration of Hef’s mag. His diagrammatic renderings are taking the place that Jack Cole’s deliciously juicy watercolors inaugurated.

Just the thought of Cole and Gurewitch pictures side-by-side makes me cringe. But it also makes my argument: the new Playboy cartoons are completely foreign to the magazine that once elevated the single panel cartoon to Art.

WITH HIS MAGAZINE no longer publishing respectable cartoons, we could say— with a vaguely poetic flourish— that Hefner’s life had lost its original meaning. And so he stopped living.

At the announcement of Hef’s death in September 2017, the supermarket’s most energetic tabloid, the National Enquirer, leaped forward with a bushel of scandalous factoids about him and his supposed last days. “In life,” asserted the newspaper, “Hugh Hefner knew a million lovers and rarely—if ever—slept alone. In death, he was a bankrupt and wrinkled recluse, withered to a skeletal 90 pounds, and cut off from even those he most loved.”

|

|

The Enquirer claimed inside knowledge about “the tortured final days of America’s most legendary Lothario.” The end, it was revealed, “was nothing like the life Hef lived” according to “a Hollywood insider.”

At the end, “he lived in shocking, urine-soaked squalor. He had to be lifted into and out of a wheelchair. Hef was desperate to hide his true condition. He wanted so badly to have his memory preserved as the swashbuckling playboy he was in youth ... the virile stud with millions of hot girlfriends.

“The truth is he became a modern-day Howard Hughes—alone, refusing to see guests, his fingernails overgrown, his breath a putrid stench, the air around him suffocating and musty.”

The official cause of death was cardiac arrest. But the Enquirer reported that he was “cancer ravaged.”

In short, the Enquirer was having the time of its life making up stuff about the man the tabloid doubtless secretly salivated over for his satyric lifestyle, details of which might’ve crammed the paper with juicy copy for years. But didn’t.

Now, the Enquirer had the opportunity to make up about Hef’s last days whatever lurid poetic justice it thought appropriate. So it did.

Although maybe not: I haven’t seen an official denial of the Enquirer version of Hef. So maybe, it’s correct.

Reactions through the so-called news media were mixed. Others in the same vein of fiction as the Enquirer included Ross Douthat at the New York Times, who wrote: “Hef was the grinning pimp of the sexual revolution with quaaludes for the ladies and viagra for himself—a father of smut addictions and eating disorders, abortions and divorce and syphilis, a pretentious huckster who published Updike stories no one read while doing flesh procurement for celebrities, a revolutionary whose revolution chiefly benefitted men like himself. ...

“Early Hef had a pipe and suit and a highbrow reference for every occasion; he even claimed to have a philosophy, that final refuge of the scoundrel. But late Hef was a lecherous, low-brow Peter Pan, playing at perpetual boyhood—ice cream for breakfast, pajamas all day—while bodyguards shooed male celebrities away from his paid harem and the skull grinned beneath his papery skin.”

Not everyone was quite so vitriolic. But Katha Pollitt at The Nation comes close, calling Hefner “a creep” and a “toxic bachelor. ... You have to ignore a lot of human suffering to buy the notion that ‘Hef’ was a fun-guy genius who brought us sexual liberation.”

Pollitt quotes Bette Midler: “Why lionize Hugh Hefner, a pig, a pornographer and a predator too? I once went to the ‘Mansion’ in ’68 and got the clap just walking through the door.”

“What brought us whatever sexual liberation we now possess,” says Pollitt, “was reliable contraception, legal abortion, and, yes, feminism. It was feminism that encouraged women to consider their own pleasure, cut through the Freudian nonsense about vaginal orgasms and ‘frigidity,’ mainstream female masturbation as a way to learn about one’s body, and pointed out, insistently, that women are not objects for male consumption ...

“Why,” she continues, “is it so hard to ask what kind of world we make when we hail as heroic a man who saw women as a pair of implanted breasts with a sell-by date of their 25th birthday? It’s a conversation that Hugh Hefner did a great deal to suppress. It’s too late for Marilyn [Monroe], but not for us. Now that he’s dead, let’s talk.”

Peggy Dexter at CNN leaves out most of the vitriol: “The terms of [Hefner’s] rebellion undeniably depended on putting women in a second-class role. It was the women, after all, whose sexuality was on display on the covers and in the centerfolds of his magazine, not to mention hanging on his shoulder, practically until the day he died.”

But the president and CEO of GLAAD (a media-monitoring organization that has grown out of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) ladled the vitriol back in, albeit using a vocabulary somewhat more sophisticated than Douthat’s. Sarah Kate Ellis criticized the news media’s coverage of Hefner’s passing:

"It's alarming how media is attempting to paint Hugh Hefner as a pioneer or social justice activist because nothing could be further from reality," she said. "Hefner was a not a visionary. He was a misogynist who built an empire on sexualizing women and mainstreaming stereotypes that caused irreparable damage to women's rights and our entire culture."

OF THE POSTHUMOUS EVALUATIONS of Hefner, I admire those of Camille Paglia, a pro-sex feminist and cultural critic, who defiantly rejects the notion that Hefner is a misogynist.

“Absolutely not!” she said in an interview with Hollywood Reporter’s Jeanie Pyun. “The central theme of my wing of pro-sex feminism is that all celebrations of the sexual human body are positive. Second-wave feminism went off the rails when it was totally unable to deal with erotic imagery, which has been a central feature of the entire history of Western art ever since Greek nudes.”

About Playboy’s cultural impact, Paglia said: “Hefner reimagined the American male as a connoisseur in the continental manner, a man who enjoyed all the fine pleasures of life, including sex. Hefner brilliantly put sex into a continuum of appreciative response to jazz, to art, to ideas, to fine food. This was something brand new.

“I have always taken the position that the men's magazines — from the glossiest and most sophisticated to the rawest and raunchiest — represent the brute reality of sexuality. Pornography is not a distortion. It is not a sexist twisting of the facts of life but a kind of peephole into the roiling, primitive animal energies that are at the heart of sexual attraction and desire.”

She adds: “It must be remembered that Hefner was a gifted editor who knew how to produce a magazine that had great visual style and that was a riveting combination of pictorial with print design. Everything about Playboy as a visual object, whether you liked the magazine or not, was lively and often ravishing. ... I would hope that people could see the positives in the Playboy sexual landscape — the foregrounding of pleasure and fun and humor. Sex is not a tragedy, it's a comedy! (Laughs.)”

THE GROWTH OF THE INTERNET prompted the magazine to develop an official web presence called Playboy Online in the late 1980s. The company launched Playboy.com, the official website for Playboy Enterprises and an online companion to Playboy magazine, in 1994. As part of the online presence, Playboy developed a pay website called the Playboy Cyber Club in 1995 which features online chats, additional pictorials, videos of Playmates and Playboy Cyber Girls that are not featured in the magazine. Archives of past Playboy articles and interviews are also included. In September 2005, Playboy began publishing a digital version of the magazine.

Then in early 2018— less than six months after Hefner’s death— Jim Puzzanghera of the Los Angeles Times reported that Playboy was "considering killing the print magazine," as the publication "has lost as much as $7 million annually in recent years.” However, in the July/August 2018 issue, a reader asked if the print magazine would discontinue, and Playboy responded that it was not going anywhere.

But not quite two years later, in March 2020, Ben Kohn, CEO of Playboy Enterprises, announced that the Spring 2020 issue would be the last regularly scheduled printed issue and that the magazine would now publish its content online. The decision to close the print edition was attributed in part to the COVID-19 pandemic which interfered with distribution of the magazine. But it was more likely the $7 million that the magazine lost annually that pulled the plug on the printed Playboy.

The magazine’s owners wanted to make money from Playboy, and when the steadily losing magazine wasn’t making money, they wanted to shut it down so the rest of the net Playboy Enterprises would pour money into their pockets.

Yes, the Playboy name continues as one of the world’s most lucrative licensing operations. But photographs of men holding the magazine in a way that permits them to fold out the triple-page centerfold are now outdated.

PLAYBOY’S FINAL SPASM before retreating into the Internet was the Playboy Mansion. The original Playboy Mansion was established in 1959—a 70-room brick and limestone residence in Chicago’s Gold Coast built in 1899. But in the early seventies, Barbi Benton, one of the longest-lasting of Hef’s girlfriends, persuaded him to buy a 29-room “Gothic Tudor” style building in Holmby Hills in Los Angeles near Beverly Hills.

Known sometimes as the Playboy Mansion West, the house includes a wine cellar (with a Prohibition-era secret door), a screening room with built-in pipe organ, a game room, three zoo/aviary buildings and a related pet cemetery, a tennis/basketball court, a waterfall and a swimming pool (including patio and barbecue area and grotto), and a basement gym with sauna below the bathhouse. The Master Suite occupies several rooms on the second and third floors. The building’s front entrance opens to a game room with a pool table in the center. This room has vintage and modern arcade games, pinball machines, player piano, jukebox, plus television, stereo and couch. Hefner likes to play games.

The house sits on 5.3 acres. Landscaping includes a large koi pond with artificial stream, a small citrus orchard and two well-established forests of tree ferns and redwoods.

Hefner moved into the California Playboy Mansion in 1974, and the place quickly began hosting glittering parties that were usually attended by celebrities and socialites galore.

But something else was also going on.

For years, the seemingly ageless Hefner embodied the “Playboy lifestyle” as the pajama-clad sybarite who worked from his bed, threw lavish parties and inhabited the Playboy Mansion with an ever-changing bevy of well-turned young beauties.

He

had money enough to construct a fantasy—an elaborate dwelling with a circus in

the surrounding grounds. Then he lived in the fantasy. Said he: “I created a

world of my own where I was free to live and love in ways most of us only dream

about.”

He

had money enough to construct a fantasy—an elaborate dwelling with a circus in

the surrounding grounds. Then he lived in the fantasy. Said he: “I created a

world of my own where I was free to live and love in ways most of us only dream

about.”

According to Hefner in an archival interview: "Much of what Playboy's all about, really, is a Disneyland for adults — a projection of those adolescent dreams and fantasies that I had growing up, that I never really lost."

And to become a kind of universal “playboy,” a voluptuary in sex, he enlisted attractive women to complete the fantasy by taking their clothes off to satiate his every sexual desire.

What American adolescent male wouldn’t share in that kind of fantasy if given the chance?

Hef had become THE Playboy, the one the magazine was all about.

BUT THE RECENTLY RELEASED A&E DOCUSERIES “Secrets of Playboy” was about a different sort of Playboy. The series features testimonies by several women who, in their younger days, lived at the Playboy Mansion and were Hef’s sexual playthings. As residents of the Mansion, they were expected to be sexually available—whenever, and however.

Hefner died almost five years ago, and time enough has lapsed to permit some of those who knew him—in particular, many former Playmates—to come forward with horrific stories about life in Hefner’s Playboy Mansion.

It's alleged that Hefner would invite members of the media to parties at the Mansion, lend them his bedroom for sex with a Playmate, and catch them in the act on film, then blackmail them later to better shape Playboy's image in the public eye.

It wasn't just members of the media who were blackmailed with compromising footage at the Mansion — the models, "stars and athletes" were also at risk. Hefner's former girlfriend (six years, late sixties through early seventies) Sondra Theodore speaks about her shock when she saw herself having sex on two screens in the bedroom which he had set up with cameras.

Theodore also claims that when other people were invited into the bedroom the couple shared, Hef would pretend to turn the cameras off at their request, but a video tape of them would emerge a week later. Stefan Tetenbaum, Hefner's former valet, also claimed that Hefner rarely participated, instead choosing to be a voyeur and a film "director" of sorts.

Theodore tells about losing her sense of self. She felt that she couldn’t be normal anymore.

And then, sex with dogs.

Theodore walked in once and found Hefner having sex with their dog. “And I said, 'What are you doing?' He says, 'Well, dogs have needs, too.' I went, 'Stop that! Stop that.' I never left him alone with the dog again. I couldn't believe what I was seeing."

In 1971, Hefner confessed that he’d experimented with bisexuality. Every aspect of sexual behavior was part of the “swing” lifestyle then prevailing in personal and private lives.

Hefner's former girlfriend Holly Madison was the focus of the second episode of “Secrets of Playboy,” and she detailed her mental state during the seven years she was with him.

Madison called the sexually charged environment within the Playboy Mansion, and Hefner's circle of girlfriends, closer to a "cult" where the women were "gaslit." She also claims that she was in more of a "Stockholm Syndrome situation" than a relationship.

Despite having several girlfriends at once, Hefner's didn't allow his girlfriends to have other boyfriends. Madison also said that while living in the house as one of his partners, she had a 9 p.m. curfew, she was encouraged to not have friends over, and she wasn't really allowed to leave unless it was for a family holiday.

Madison details how she wanted to keep her waitressing job for one day a week as a safety net but Hefner asked her to quit because it "made him jealous." Instead she and the other girlfriends were given $1,000 a week as an allowance.

The series says Hefner engaged in rampant drug use—quaaludes and cocaine mostly— and hosted occasional “Pig nights” for which he’d hire a dozen unattractive prostitutes off the street to have sex with his friends.

Hef’s harem of girlfriends was completely controlled by him. Several of them asserted that they were afraid to leave. Said Madison: “If I left, there was this mountain of revenge porn waiting to come out. It was just gross.”

BOOKS WRITTEN BY SOME of Hefner’s former girlfriends describe the sex routine at the mansion. Hefner was clearly enacting an adolescent fantasy in which he is THE Playboy, doing all the things the magazine encouraged for an American male.

Twice a week—on Tuesdays and Thursdays, as I recall; always the same days, week after week— Hef and his girlfriends (4-6 of them) would go out for dinner and a few hours at a night club. An hour before they left the club, Hef would take a viagra pill that would help him to achieve an erection later. (Viagra takes an hour to become effective.)

When they returned to the mansion, they’d all retire to Hef’s bedroom, which was equipped with various amusements for sexual entertainment. While they’d all watch a pornographic movie, one of them would give oral sex to Hef to get him erect. Then, he’d have sex with one or more of the group. If a girl didn’t want to have sex with Hef that night, she’d wear panties. Makes me wonder what would happen if they all showed up wearing panties some night.

The sexual relationship was short, less than a minute. A girl would straddle Hef, who lay on his back on the bed, and he would make a couple thrusts, then the girl would quickly get off, and the next victim would mount him. No kissing or other acts of intimacy.

The sex ended when Hef masturbated, crying “God damn it —wow!” as he ejaculated. Both the action and his utterance occurred exactly the same every time, with such predictability that the girls mimicked his words and snickered.

The antics of the group during the evening were filmed. Sometimes Hef didn’t have sex with anyone: he played movie director and merely observed the proceedings, which sometimes involved men friends as well as girlfriends.

Hefner’s son Cooper slammed the A&E docuseries, saying the salacious stories are “a case of regret becoming revenge.”

When I had seen only a couple of the series, I tended to believe Cooper rather than a former Playmate who believes she was a captive of the "Stockholm Syndrome" while in a sexual relationship with Hefner. But that was only a tendency not a conviction. And by the time I’d finished viewing the series, I’d changed my mind. I believed the women.

As of this writing, I’ve watched all twelve episodes of the series. The fifth was occupied almost entirely by testimony from Miki Garcia, who was director of Playmate Promotions for 3 ½ years. She booked Playmate models who were invited to go out on promotions—as greeters, say, for the opening of a restaurant or nightclub where their presence promoted all things Playboy as well as the restaurant or nightclub. The models often found themselves sexually attacked by the persons who booked their appearance. Under those circumstances, Garcia was in effect pimping the girls out on “dates.”

One of Garcia’s chief concerns pretty soon was protecting the girls from the predations of men who frequented Playboy Clubs in order to fondle the Bunnies. Protecting the girls while at the same time deliberately sending them out into risky situations sounds like the ultimate recipe for frustration.

Garcia kept her sanity by keeping records about the various misbehaviors of Hefner and his circle. We don’t have to think long about her activities before they begin to sound a lot like regret turning to revenge. That’s what they were—but they were fully justified by what Garcia observed and experienced.

Garcia’s other preoccupation was to advance up the corporate ladder. At higher elevation, she planned to do something to correct the behaviors that threatened the models. But she didn’t succeed in this ambition, probably, she believes, because it was widely known that she wouldn’t sleep with Hef in order to achieve her objective.

Dopes Hefner deserve this kind of scrutiny, this kind of judgement? Undoubtedly. His bizarre preoccupation with sex—his regimentation of it— is alone justification for continual examination. And in the sixth episode of the series, Garcia tells us of one of the ways Hef’s behaviors ruined the lives of young women: his promotion of drugs to enhance the sexual experience made drug addicts of some of the women.

In successive episodes, the activities of Hefner and his circle become more and more sinister and fraught with dangers for young women. Repeatedly, it is emphasized that to Hef and his friends, the women were playthings and nothing more, and no one ever thinks to ask for their consent. Their role was to be sexually available. If this is the Playboy attitude, it does not bode well for either the female or the male population

WATCHING THE FIRST TWO EPISODES of the docuseries, I kept wondering how these women let themselves become ensnared in Hefner’s fantasy. Did they know what they were in store for? What did they think they were getting into? Playing sandbox?

No. What they thought was that they were en route to a career as a model.

Very soon after Playboy’s success as a magazine, Playmates became models of femininity. Young girls growing up aspired to have bodies like Playmates.

Many, if not most, of the young women who took up residence in the Playboy Mansion were teenagers. They had come to Los Angeles in search of a career in movies or as a model. And living at Playboy Mansion was regarded as a step in that direction. It was a step in another direction, too, but the girls were apparently too inexperienced to recognize an invitation to the Mansion as the beginning of a sexual enslavement.

In assembling members of his harem, Hef’s probable initiating maneuver was to recruit a woman to be one of his girlfriends, which, at first blush, sounds innocent enough particularly since he doubtless failed to mention at the beginning that regular group sex would be part of their relationship. Being girlfriend to an old gaffer like Hef certainly didn’t seem threatening. Sometimes girls were recruited by members of the group. Hef then groomed the new recruit, slowly bringing up the possibility of sex—first with him, and then with everyone else, too.

His method (as I have imagined it) was to sell the new recruit on the notion of “freedom”—they’d be free to do whatever kind of sex their wildest fantasy imagined. Not the puritanical sex of their upbringing but wild, imaginative sex. Sexual freedom was symbolic of freedom generally, the kind of freedom upon which the nation was founded. Sexual freedom, then, became essentially patriotic and a rejection of the staid out-dated standards of their parents. And with young enough women, thoroughly twitterpated,* that worked. The next thing they knew, they were romping regularly in their new found freedom.

Drugs were part of the routine. Hef and his girlfriends regularly sought to enhance their enjoyment of sex by taking drugs—quaaludes and cocaine. But recreational drugs have been part of American sex lives for years so Hef was scarcely doing anything that was socially unusual. Until he began using drugs to seduce women.

Two of the women testifying in the docuseries told similar stories. They had been nervous about what they would be doing as residents of the Mansion, and they went to see Hefner about their uneasiness.

Playing the thoughtful uncle, Hef invited them into his bedroom, and during their conversation, he offered them a drink—and then put a pill into the drink.

Both of the women said they were soon unconscious: the next thing they knew, they were on their backs in Hef’s bed, their clothing partially removed, and Hef dozing, also naked, by their sides.

Several of the docuseries witnesses claimed that after a few years, some of Hefner’s playmates left the Mansion as drug addicts.

Hefner’s being an attractive and very very wealthy man didn’t hurt his chances either. Wealth and power are, after all, aphrodisiac. And as Playboy’s fame and power grew, Hefner clearly realized he could deploy such matters to his advantage personally—sexually—as THE Playboy living the life of his adolescent fantasy.

Hefner did other things, too.

HE WAS A POLITICAL ACTIVIST in the Democrank Party and he was a crusader for First Amendment rights, animal rescue, and racial equity— all admirable causes.

Hefner donated $100,000 to the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts to create a course called “Censorship in Cinema” and he gave $2 million to endow a chair for the study of American film. In 2007, the University’s audiovisual archive at the Norris Theater received a donation from Hefner and was renamed the Hugh M. Hefner Moving Image Archive in his honor.

At Playboy, the Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Award was created “to honor individuals who have made significant contributions in the vital effort to protect and enhance First Amendment rights for Americans.” In Playboy Clubs, racial diversity was actively encouraged and campaigned for.

In 1978, Hefner helped organize fund-raising efforts that led to the restoration of the Hollywood sign; he contributed almost a tenth of the total restoration costs by purchasing the letter Y in a ceremonial auction.

Through his charitable foundation and personally, Hefner contributed to charities and other organizations outside the sphere of politics and publishing—animal rescue and Children of the Night (which serves abused children), for instance. From the latter, he received the organization’s first-ever Founder’s Hero of the Heart Award in appreciation for his unwavering dedication, commitment and generosity.

Seeking

a more rounded view of Hefner than “Secrets of Playboy” offers, I viewed the

2010 DVD “Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Activist, and Rebel.” In this 2-hour

extravaganza, we see another Hugh Hefner. Herein, he is the champion of every

left-of-center cause in the country, the savior of Western civilization. He is

respected—even beloved. Mike Wallace says he trusts Hef.

In the DVD, Hef is a serious thinker and an avuncular activist, an innovative rebel crusading for a less repressive society. He works for the legalization of contraception and abortion, not to mention marijuana and Lenny Bruce.

Dr. Ruth says of Hefner that “it’s too bad he mixed up his personal life with his mission because that made taking his mission seriously difficult.”

Yes, Hefner did all these things in the name of liberty and freedom and a civil society. Some things he did out of a passion for the cause, whatever it may be. Sexual liberation, freedom of speech and the press. Some, like freedom of press, were also more self-serving: they helped assure that his magazine could go right on publishing pictures of naked women.

Son Cooper made the following statement at the time of his father’s death:

“My father lived an exceptional and impactful life as a media and cultural pioneer and a leading voice behind some of the most significant social and cultural movements of our time in advocating free speech, civil rights and sexual freedom. He defined a lifestyle and ethos that lie at the heart of the Playboy brand, one of the most recognizable and enduring in history. He will be greatly missed by many, including his wife Crystal, my sister Christie and my brothers David and Marston, and all of us at Playboy Enterprises.”

Well, he left out something. He left out the “Secret Playboy.” And that is to be expected: at the time, Cooper was Chief Creative Officer of Playboy Enterprises. Since then, he and all the rest of the Hefners have withdrawn from the family business.

But his farewell to his father left out the voluptuary whose lifestyle corrupted young women, the selfish sexual liberator whose personal life was the chief beneficiary of the crusade.

Robin Abcarian wrote in the Los Angeles Times, quoted in St. Wikipedia, that Hefner “probably did more to mainstream the exploitation of women’s bodies than any other figure in American history,” adding that he “managed to convince many women that taking off their clothes for men’s pleasure was not just empowering but a worthy goal in itself.” He embodied the aesthetic notion that images of women—and women themselves—exist to please men.

And as Theodore said, more than once during “Secrets of Playboy,” addressing an unseen but pervasive Hef, “You’re not getting away with this.”

The secret is out. It has been revealed.

The magazine is dead. But the cartoons Hefner and his magazine fostered live on in the history of the medium as exemplars of the artistries to which cartooning aspires.

Futnit. Various aspects of Hefner’s life and career as well as the history of Playboy can be found elsewhere in Harv’s Hindsights for September 2008 and October 2017. And in Opus 349. The interview with Michelle Urry appears in Hindsight on October 2006. Jack Cole is examined in November 2003, and Buck Brown in October 2007.

*Twitterpated (adj.)—infatuated, besotted, in a state of happy, giggly nervous excitement.