|

Frank

Willard and A Touch of Moonshine

Lowbrow

Comedy for the Masses

If

cartoonists were typecast according to their creations, Frank Willard would

undoubtedly win the prize (if prizes were awarded). He was very nearly the

perfect incarnation of his eponymous comic strip protagonist, Moon Mullins. Or

so Clive Howard, in his article “The Magnificent Roughneck” (Saturday

Evening Post, August 9, 1947), would have us believe.

“To

put it bluntly,” Howard said, bluntly, “Moon Mullins is a bum.” And Howard went

bluntly on: “His banjo eyes are always a little bleary from lack of sleep and

vague but doubtless colossal dissipations. He has never, in all the years that

the public has had the opportunity of observing him [68 altogether], been known

to do an honest day’s work. He wears his derby hat as a badge of insolence

which he refuses to remove even in the livingroom, much less the elevator.

Toward young women, he is invariably forward, not to say disrespectful. He is

the sworn foe of all bill collectors and a devotee of pool halls, cigars, long

yellow roadsters and what Broadway calls the fast buck.”

Not

surprisingly—given the bias Howard unveils in his article—Willard, like Moon,

“hates to work and has spent most of his life trying to get out of it. He also

hates office hours, business lunches, dress suits, dinner parties and all other

common appurtenances of success.”

But

Willard, unlike Moon, was a resounding success. At the time of the publication

of Howard’s article, the combined daily circulation of the 350 or so newspapers

carrying Moon Mullins was 14 million (19 million on Sundays); it ranked

among the top half dozen comic strips of the day. And Willard was a wealthy

man.

But

his habitual garb scarcely suggested wealth. He usually wore a sweat shirt and

rumpled slacks. Once he failed to engage a new gardener because when the

applicant arrived for an interview, he saw Willard working on his lawn in old

pants and an undershirt and so the applicant left because he thought the job

had already been taken.

“On

those rare occasions when he wears a double-breasted suit,” Howard writes,

Willard looks “a great deal like a successful banker. However, any discerning

observer soon notices that Willard likes to sit on the middle of his spine,

that he usually talks through a cloud of cigar smoke, and that he holds the

cigar in his left hand in the same way that a veteran pool play supports a

cue.”

Willard

has, Howard assures us, “only two great loves in his life, neither of them

conducive to prosperity. The first is pool, which he had to give up early in

life for lack of skill.” The other is golf, to which Willard devotes himself

most of every week.

Willard’s

inclination to indolence and work avoidance manifested itself early in

life.

Frank

Henry Willard was born on September 21, 1893 in Anna, Illinois, the son of

Francis William Willard, a dentist (some sources say “surgeon,” but they’re

wrong according to the testimony of his son), and Laura Kirkham. Although

his father wanted him to follow in his footsteps, young Frank never finished

high school. “Got tossed out for something or other,” Willard told Martin

Sheridan (Comics and Their Creators), “—and was promptly placed in a now

defunct institution—Union Academy. After being a sophomore for several years,

they decided that the only way of getting me through school was to give me the

old heave-ho—which they did to our mutual delight.”

Young

Frank left home at about the age of seventeen to join another youth in running

a concession with a traveling carnival throughout southern Illinois.

While his partner ran the hamburger stand, Willard played the horses, and they

split the profits on both enterprises. The business collapsed one day

when his partner "became interested in trains" (as Willard put it to

Sheridan) and took all the receipts to California, leaving Willard to pay all

the bills, thereby depleting entirely whatever profits his winning at the races

had generated.

In

hindsight, compensations were revealed: “I met a lot of interesting people in

that business—some very able tattoo artists, pickpockets, ballyhoo men, shills,

etc.,” Willard said. “They might have had some influence on Moon,” he

concluded.

Willard

next took a position as a claim tracer with a Chicago department store and

conned a friend into doing all the work by supplying him with lunch (sandwiches

that Willard obtained at the free lunch counter in a nearby saloon). At

night, Willard attended classes at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. And he

also freelanced cartoons to local newspapers.

In

1914, Willard sold an editorial cartoon about the outbreak of World War I to

the Chicago Tribune, whose two political cartoonists happened, that day,

to be away from their drawingboards.

“John

McCutcheon was in Mexico,” Willard told Marcia Winn in the Los Angeles Times (December 12,1943), “and Frank King, who used to pinch-hit for him, was on

vacation, so I thought, ‘Well, what the hell, here’s the war starting and the Tribune with no cartoon for the front page,’ so I went home and drew one.”

The Trib took the cartoon and ran it on the front page, four columns wide.

(We’ve posted it in our Willard Gallery at the end of this disquisition.) Said

Willard: “That was August 1, 1914. I’ll never forget it. ... I quit my job and

spent the whole day walking around Chicago looking at Tribunes on the

newsstands with my cartoon on the front page. Thought everybody in Chicago was

doing the same thing. Wore out a $3.50 pair of shoes.”

Willard’s

success went immediately to his head: deciding forthwith that he was a

political cartoonist, he offered to go to work at it full-time on the Tribune staff, and when his offer was declined, he applied at the Chicago

Herald.

After

listening to him for five minutes, the Herald’s managing editor, the

legendary James Keeley, let him down, not too gently: “Son,” said that worthy,

“you haven’t enough brains to be a political a cartoonist.”

“Then

how about a comic strip,” said the irrepressible Willard, inadvertently

admitting that one doesn’t have to know much to be a comic strip cartoonist.

Keeley

confirmed Willard’s opinion: “Well, maybe you’re dumb enough for that,” he said

(quoted by Willard in Comics and Their Creators) and hired him at twenty

dollars a week.

Willard

did a Sunday strip called Tom, Dick and Harry about the shenanigans of a

band of miscellaneous school kids. He also did another strip, Mrs. Pippin’s

Husband, and “a so-called humorous cartoon.”

Like

other newspaper staff cartoonists of the time (including two of his bullpen

cohorts, E.C. Segar and Billy DeBeck, neither, as yet, known for their

masterworks, Popeye and Barney Google), Willard worked all day in

the Herald art department, drawing whatever was needed—including several

unnamed, discontinuous comics features, one of which we’ve posted in our

Willard Gallery down yonder.

Willard

had barely gotten started when he was drafted into the American Expeditionary

Force, wherein, Howard tells us, “he rose three times to sergeant and three

times was busted back to private.” When the war ended, he returned from France

and found himself in New York, where he became a staff artist for King Features

Syndicate, for which he did several comics features—Penny Ante, Let the

Wedding Bells Ring Out and yet another undistinguished strip called The

Outa Luck Club about a family man named Luther Blink. The strip was

credited to Dok Willard, the cartoonist’s deliberate misspelling of a nickname

he had acquired as the son of a doctor of dentistry.

One

day in the spring of 1923, Willard engaged in a dispute with his editor and

settled it with his fists. The confrontation took place over a matter of

proprieties. Willard showed the editor, the famed Rudolph Block, some ideas for

gags, and Block rejected them. A few weeks later, Willard saw those same ideas

in George McManus’ Bringing Up Father. Block was stealing his ideas and

passing them on to McManus. Understandably miffed, Willard stormed into the

office and pasted Block one. (A miffed Willard was not to be trifled with.)

Willard

won the fight but lost the job. It was, however, a loss as fraught with

historic significance as the notorious “long count” prize fight a few years

later in which Jack Dempsey was robbed of a victory over Gene Tunney because he

took too long getting to a neutral corner. (Tunney thus had more than the

prescribed ten seconds to get up after Dempsey had floored him.) In Willard’s

case, it was a newspaper publisher who counted.

When

Joseph Medill Patterson, publisher of the New York Daily News and head

of the Chicago Tribune-Daily News Syndicate, heard of the Block imbroglio, he

sent for Willard and offered him a job doing a new strip that he’d been mulling

over. The Daily News was the nation's first successful tabloid,

screaming headlines and scandals galore, and Patterson wanted a comic strip

tailored expressly for his sensation-hungry readers. He wanted a strip

about the low life of the city, about roughnecks and confidence men who made

their way with their wits and pure gall in total disregard of the Puritan work

ethic, books of etiquette, and every other refinement. Judging from what

he had heard of Willard's character, Patterson thought the cartoonist would be

able to produce just what he wanted. And that's what Willard did.

The result was a classic comedy of conniving, brawling, uncooth social

pretension, Moon Mullins.

Beginning

June 19, 1923, the strip at first concentrated only on the title character

(named by Patterson, who seized upon a nomenclature just then emerging on the

social horizon in those early years of Prohibition, moonshine; for the

character’s last name, Willard and Patterson consulted the phone directory and

landed on a plumbing company, Mullins and Sons.)

Patterson

launched the strip in the sports section of the Daily News, and the

first sequence capitalized on mounting public interest in the forthcoming prize

fight between Jack Dempsey and Tommy Gibbons in Shelby, Montana. At the time,

Dempsey was having trouble keeping sparring partners, so Moon enlists a black

guy named Wildcat, whom he plans to “rent out” to Dempsey as a punching bag. To

get to Montana, Moon sends himself and Wildcat off to Shelby in a shipping crate,

their arrival detailed in the inaugural strip (which we’ve posted in the

Willard Gallery along with other historic moments in the strip’s run).

Although

Patterson intended the strip to appeal to sports fans, the sporting milieu

disappeared fairly soon. According to Willard’s long-time assistant, Ferd

Johnson (he began assisting the second month of the strip’s run), Willard

couldn’t keep coming up with sports ideas even when Patterson sent him to

baseball training camps in Florida. After a few months, Willard abandoned

locker rooms and concentrated on poolrooms where Moon began to shine.

Moon

is an unabashed free-loader, a con man, always on the look-out for a free lunch

and a quick buck and willing to let anyone take the risks but himself. He

fails more often than he succeeds. His only redeeming quality is his

endurance: he keeps at it. Disappointed at the outcome of one con,

he immediately goes on to the next, not bothered one whit by failure.

Moon's motives are undisguised by the usual veneers of civilization's

respectable society. And he is entirely forthright. His honest

embracing of his own self-interest is refreshing, and that is his charm.

At

first, Moon presented a no-neck, square-jawed visage, but within a few months,

the jaw receded and the classic “moon-faced” stalwart appeared. By then, he’d

already run into the siren who would monopolize his time for much of the next

decade or more—Little Egypt, named for what Willard called a well-known

“hootchy-koochy dancer.” (The dancer called Little Egypt in real life appeared

in the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago; the name became generic for any belly

dancer, and, indeed, two Little Egypts danced at the Fair.)

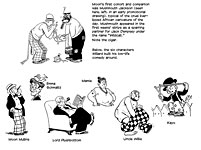

Otherwise,

Willard surrounded Moon with kindred souls—Lord and Lady Plushbottom (the

former, a harmless pompous fugitive from some peerage somewhere; the latter,

formerly the spinster Emmy Schmaltz, angular and vinegary owner of the boarding

house where they all live), rotund ne'er-do-well Uncle Willie (always in need

of a shave) and his slovenly wife, Mamie (nee McAshcan), the cook. Moon's

diminutive kid brother Kayo (who slept in one of Moon's bureau drawers) was the

only realist (and he was a full-blown cynic).

As

Stephen Becker says (in Comic Art in America): the strip was

"the greatest collection of social pretenders ever assembled. ...

The impulse is always upward— to fame, riches, dazzling lights. But the

culmination is always a descent to reality, via the nightstick, the pratfall,

or the custard pie. Always, earthly reality wins out over the ideal, the

pretension; beef stew defeats poetry."

John

Lardner called the strip a "permanent monument" to an easier time

when lower and middle classes overlapped. But it was also definitely

low-brow: "[In] their way of life, which was the natural way, for

them, of attrition ... if they had to choose between a necessity and a pleasure

to spend a couple of bucks on, they invariably went for the pleasure. But

the primary rule of their existence, and Willard never let them forget it, was

that they did not have the couple of bucks."

Assisted

by Ferd Johnson (who was soon doing his own strip, a mock cowboy epic on

Sundays, Texas Slim, August 30, 1925 - February 12, 1928; revived twice,

once sharing the marquee with Dirty Dalton—“Patterson wanted a villain”),

Willard drew in what has been called “the Chicago Style,” solid linework of

unvarying width which eventually was embellished by a gritty, hayey treatment

that is perfectly in tune with the threadbare vulgarity of the strip's lower

class setting.

A

procrastinator of epic dimension, Willard postponed work on each week's batch

of strips (six dailies and a Sunday page) until the last possible moment. So

habitual was his dillydallying that the syndicate began phoning him every

Monday for strips that were due on Friday. A couple days later, Willard would

tell his wife, Marie (nee O'Connell), that he was “going to work today.” But he

invariably finds an excuse to put off going to work for another few hours—he

goes downtown to get a haircut, takes detours into hardware, drug and dime

stores, and otherwise fritters away the morning hours until it is too late to

contemplate doing anything on the strip before lunch: it would be foolish to

begin work with so little of the morning left to work in.

When

he finally gets into his studio in the afternoon, he spends several minutes

sharpening every pencil in the place—then adjusting the light over his

drawingboard. Finally, as daylight wanes, he phones Johnson, summoning him to

the battlefield.

“From

the time Johnson arrives,” Howard relates, “the two men work without

interruption, sustaining themselves on black coffee and cigars, until they have

finished. ... The job takes anywhere from thirty-six to forty-eight hours. At

the end of it, Willard falls into bed exhausted and sleeps practically around

the clock”—that is, twenty-two to twenty-four hours straight.

Howard

exaggerates. But, like Willard, only to make a good story better. Not every

week concluded with an all-night crescendo. Most of the time, according to

Johnson, the two played golf all day but worked on the strip at night. And

Willard, who was a boozer of mythic attainments, drank all night. That’s one

reason they worked at night: Willard’s wife kept an eye on her husband, but she

was asleep at night.

Said

Johnson, describing their working lives when living in New Canaan, Connecticut

one winter: “He’d kill a quart, maybe a bottle, of gin a night. I didn’t touch

the stuff. I’d learned that somebody had to stay awake. And come the

morning, I was the one—I’d get rid of the bottles, the empties, slip them in my

pocket, as soon as I got out of the house, toss them in a snowbank. Come

spring,” he finished with a laugh, “there was a glass fence of bottles.”

Sometimes,

catastrophically, Willard arrived at the moment of truth before his

drawingboard and found his mind a complete blank. Not a joke in sight. When he

misses his deadline, the syndicate resorts to “wallpapering,” Howard reported.

“The editors cut characters and scenes from old strips, paste them together and

invent dialogue as close to the Willard tradition as possible.” Willard gets no

pay for “wallpaper weeks.”

Once

Willard decided that his work week would be more productive if he worked a

regular 8-hour day in an office. He took weeks to find a likely location and

weeks more to outfit the place properly. On his first day “at work” in his

office, he left after fifteen minutes and went home.

“Can’t

work in that place,” he told his wife, “—it’s too lonesome.”

His

wife advised him to hire a secretary for company.

He

looked at her with an aggrieved expression. “Honey,” he sighed, “you know I

can’t work when there are people around.”

Willard

traveled around the country with the seasons to a succession of

residences—Poland Springs, Maine; Los Angeles, California; Tampa, Florida;

Greenwich and New Canaan, Connecticut—where he chased the little white ball on

every day of the week that he wasn't bent over his drawingboard. Johnson

and his wife faithfully followed Willard and Marie to every new locale.

When Willard died on January 12, 1958 (suddenly, a week after suffering a

stroke), Johnson inherited the strip, which he continued over his own signature

for another twenty years. (Ferd’s son Tom started collaborating on the strip

the year his father took it over and co-signed it for the last 13 years until Moon

Mullins ceased in 1991). In an interview in Nemo No.29, Johnson said

he’d been doing most of the drawing since 1933; most of the writing by 1943.

By

1948, Willard was not able to do the work at all, Johnson said: he got

diabetes, had a heart attack and a stroke. For the last ten years of Willard’s

life, Johnson did all the Moon lighting. By the time Moon went

down, Johnson had been intimately associated with it for the entire 68 year

run.

In

the Willard Gallery just at your eye’s elbow, we’ve posted various of Willard’s

works, emphasizing the historic moments in Moon Mullins—the debuts of

Moon, Emmy Schmaltz (March 3, 1924), Kayo (July 4, 1924), Lord Plushbottom

(January 1,1925), Mamie (May 28, 1928), Uncle Willie (July 11, 1928)—plus a few

curiosities: Ferd Johnson’s appearance in the strip, Emmy’s threatening to

divorce Lord Plushbottom, and Uncle Willie getting a shave.

Just

at the exit of the Gallery, is a genuinely Historic Document. In 1987, Ferd

Johnson drew for cartoonist and comics chronicler Ed Black a floorplan of the

sixth (top) floor of the old Chicago Tribune office building, showing

which cartoonists worked in which offices—Sidney Smith (The Gumps), Carey

Orr (editoonist), Harold Gray (Little Orphan Annie), Gaar Williams

(miscellaneous daily panels; then, in the 1930s, The Strain on the Family

Tie), Carl Ed (Harold Teen), Frank King (Gasoline Alley), and

Willard and Johnson. He also shows the office of Arthur Crawford, manager of

the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News Syndicate, whose assistant, Mollie

Slott, actually ran the operation.

At

the lower left, Johnson points out the window next to which his drawing table

was located. Various of the Trib’s executives, including Patterson,

often played tennis on the roof just outside that window, and to get to this

“tennis court,” they clambered over Johnson’s drawing table. Johnson always

placed “some kind of a cartoon” on his drawing table, “in a prominent place

where they couldn’t help but see it. After a couple years of this, Captain

Patterson decided I could do a Sunday page—a full page in the Chicago

Tribune when I was 19!” The full pager was Johnson’s Texas Slim.

In

his final annotation, Johnson says the office arrangement depicted here was

“about the same” when the Trib moved to its new flamboyantly soaring

Gothic headquarters, the Tribune Tower, in 1925.

Bibliography.

Biographical information on Frank Willard can be found in Comics and Their

Creators by Martin Sheridan (1944) and in more extensive form in "The

Magnificent Roughneck" by Clive Howard (Saturday Evening Post, August

9, 1947). Willard is extensively quoted by Marcia Winn in an interview

published in the Los Angeles Times (December 12, 1943) but written,

probably, for her own paper, the Chicago Tribune; since Willard liked a

good story a little better than unvarnished facts, some of what he says should

be taken with a few grains of the proverbial salt. Stephen Becker provides the

best appreciation of the strip in his Comic Art in America (1959).

An obituary appeared in The New York Times (13 January 1958), and in Newsweek (27 January 1958), John Lardner paid tribute to Willard. Several

collections of Moon Mullins strips were published by Cupples and Leon

(1923-31), two of which have been reprinted in Moon Mullins: Two

Adventures (1976). Ferd Johnson supplies information about Willard and his

own experiences with Moon in Nemo No.29 (February 1989). Since

May 2000, Spec Productions has been issuing reprint volumes, starting with the

first strip; with the twentieth volume this summer, the project has reached July

4, 1935. Spec has an extensive catalogue of reprint tomes (Dick Tracy,

Gasoline Alley from the start, Alley Oop, and more); visit

specproductions.com for the list.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |