JOHN T.

MCCUTCHEON

DEAN OF

AMERICAN CARTOONISTS

Gentleman

Adventurer and Inventor of the Slow Ball

WHEN THE CHICAGO

TRIBUNE was a serious newspaper back in the early 20th Century,

it ran a cartoon on the front page, above the fold—every day. And for over 40

years, that cartoon was drawn by John McCutcheon, an unlikely suspect. A tall,

gangly, boney man with generously proportioned facial features, he looked every

bit the part that so many of his hayseed characters played in the down-home

country cartoons he was famous for drawing. But appearances, like the modest

blushes of the farmer’s daughter, can be misleading if they aren’t downright

deceiving. And they were with John Tinney McCutcheon: he was among the most

cosmopolitan and worldly wise of his fellows. And he was something more than a

cartoonist: he was a war correspondent, combat artist, news photographer, and

world traveler.

McCutcheon

drew newspaper cartoons for sixty years until he died in 1949. For years prior

to his death, he was called the Dean of American Cartoonists, a title conferred

upon him, he said, because “I’ve managed to survive the various hazards of

peace and war and my aging contemporaries have either died or found a better

way to spend their time.” By the end of the first decade of the twentieth

century, he was well on his way to the deanship.

He

was born May 6, 1870 on a farm near South Raub in Tippecanoe County, Indiana.

“I was born in a farmhouse on a gentle hilltop eight miles from Lafayette,” he

later wrote. “It was surrounded by cornfields. Not far away was the site of the

Indian village of Ouiatenon on the Wabash. ... Nearby were the Shawnee Mound

(named fo that tribe of Indians), the Wea Plains, the Big and Little Wea

Creeks, named for another tribe. ... The newspapers that occasionally reached

us were full of the Indian warfare in the West, culminating in the Custer

massacre [in 1876]. There is a family story that, at the age of five, I rushed

to my mother, announcing that I had been attacked by Indians.

“On

all sides suggestions of Indians and Indian warfare were always present” he

continued. “The early fall saw the tasseled rows of corn like the waving spears

of Indians, and a little later came the corn shocks, so much like tepees in the

haziness of Indian summer. Undoubtedly in my boyish imagination all these

impressions were registering. Many years later, seated at my drawing board in

Chicago, wondering what I could draw for the next morning’s paper, out of the

deep past came the images that resulted in ‘Injun Summer,’ which many people

call their favorite cartoon.”

His

father, John Barr McCutcheon was a Civil War veteran, a drover with literary

aspirations and, later, sheriff of Tippecanoe County and city treasurer of

Lafayette; his mother was Clara (Glick) McCutcheon. Young John spent his childhood

in the rural areas near Lafayette and carried country life with him in his

memories all his life. That, and newspapering.

When

John was about twelve, the McCutcheons moved to Elston, “a community of thirty

or forty houses scattered along a mile or so of the Romney Road leading south,”

according to Vincent Starrett, writing the biographical introduction to John

McCutcheon’s Book in 1948. For a while, John published a hand-printed

newspaper called the Elston News, “with a circulation of one. It was

illustrated with crude cartoons boosting the candidacy of Grover Cleveland.”

John was a little more successful as a playwright: he wrote “The Blunders of a

Bashful Dude,” which was produced at the local schoolhouse and ran for two

nights.

At

the age of sixteen, McCutcheon entered Purdue University and graduated four

years later with a B.S. degree in industrial arts. He’d started out in

mechanical engineering, but it was a course full of the “most malignant form of

mathematics” and when a sympathetic friend told him industrial arts had

practically no mathematics, McCutcheon transferred gratefully.

About

his social life, a Sigma Chi fraternity brother, George Ade, wrote: “He

attracted a good deal of attention on the campus by wearing the only cutaway

coat, a long-tailed affair. He wore his hair extra-long, too, and was marked as

a comer.”

Sigma

Chi was Purdue’s first fraternity, and McCutcheon was a founding member. He was

co-editor of the University’s first yearbook, the Debris, and he wrote a

weekly gossip column for the Lafayette Journal and also contributed to

the new campus newspaper, the Exponent, which he helped to start. After

graduation in 1890, McCutcheon went to Chicago where he doubled the one-man art

department of the Chicago Daily News.

NEWSPAPER

ARTISTS furnished all the illustrative material for the papers of the day. The

halftone engraving process for reproducing photographs had been perfected in

1886, but it was not adapted successfully to the big rotary presses until the New

York Tribune did it in 1897. Until the turn of the century, newspaper

sketch artists were graphic reporters, covering all the events that

photographers were to cover later. McCutcheon drew pictures of everything. He

illustrated major news events, often working from sketches made on-the-spot. A

typical day might include a trial in the morning, a sporting event or crime

scene or a local catastrophe in the afternoon, and an art show opening or a

flood or fire in the evening. When not dashing from event to event with a pad of

paper under his arm, he worked in the office, doing portraits of politicians

and dignitaries, and decorations for a variety of columns and stories. At the

beginning, he was more illustrator than cartoonist, and he also wrote

occasional feature pieces and newsstories.

Less

that a year after McCutcheon’s arrival in Chicago, George Ade came to town and,

on the strength of McCutcheon’s recommendation, found a job as a reporter at

the Daily News. In 1892, the two began a long collaboration as writer

and artist, covering the construction and then the ensuing action of the

World’s Columbian Exposition under the heading “All Roads Lead to the World’s

Fair.”

Ade

and McCutcheon continued the fellowship of their college days by sharing a room

together and by attempting to see and do everything see-able and do-able in

Chicago. They were inseparable companions in work and play for nearly eight

years. Their adventures stimulated Ade’s wit, leading to a popular long-running

series in the paper called “Stories of the Streets and the Town,” which took

the place in the paper of their World’s Fair articles after the Fair closed.

McCutcheon illustrated these efforts, and their joint productions were

collected in book form.

“Tagging

along after George,” McCutcheon wrote, “he chronicled and I illustrated almost

every phase of Chicago’s life and activities, although at the time, we did not

suspect we were passing through what later decades would call the Gay Nineties.

As I remember it, there was joy and zest and adventure in everything we did.

There was a lot of hard work, too; but now, in retrospect, it didn’t seem like

work. Anyway, we had nothing else to do.”

Ade

went on to become a noted humorist and playwright, but not before he wrote a

line or two of comics history.

Victor

Lawson, the publisher of the News, liked McCutcheon’s work, and when the

presidential campaign of 1896 commenced, he gave the artist a five-column

front-page hole to fill every day. Lawson wanted a cartoon, a humorous drawing

rather than a news picture, but McCutcheon thought of himself as a realistic

newspaper artist. Suddenly, as McCutcheon recalled it later in his

autobiography, “I had to be made over into something requiring whimsy and, if

possible, humor. In this transition, George helped materially. He provided the

excellent suggestions that gave my early cartoons whatever distinction they

had.” With Ade at his elbow, McCutcheon got through the transition from artist

to cartoonist and was soon able to stand on his own.

The

William McKinley-William Jennings Bryan presidential race was a particularly

bitter contest, McCutcheon recalled, “and there was rich material for

cartoons.” And since the News had the largest morning circulation in

Chicago and his cartoons were on the front page, they were noticed.

One

day, putting the finishing touches on his cartoon, McCutcheon casually and

without forethought filled an empty place in the picture by drawing a

floppy-eared dog in the space—“an ordinary sort of dog,” he said, “the kind you

could buy for about a dollar a dozen.” The next day, again faced with a few

spare square inches in his cartoon, McCutcheon inserted the dog. “That

afternoon,” Starrett wrote, “a letter came in, asking what the dog meant. It

had been there twice, and a reader wanted to know if it had some subtle

significance.” It didn’t, but McCutcheon put the dog in the next day’s cartoon,

and “twelve more letters came in demanding to know its meaning. Thereafter, the

pooch appeared regularly in nearly every cartoon.”

For

a while, when the dog didn’t appear, it excited notice among letter writers:

What has become of the dog? Where is the dog? Has the dog died? Have the

politicians talked the dog to death?

Starrett

finished: “Friends on the paper’s staff wondered if the mystery of the dog was

not creating more interest than the presidential campaign. In such fashion did

McCutcheon’s droll pup take its place among the lovable dogs of humorous

literature.”

In

1895, McCutcheon and Ade had gone to Europe together, sending stories with

illustrations back to the News twice a week. Their partnership again

resulted in a book. More significantly, the trip gave McCutcheon’s itch to

travel a tantalizing rub, and when next he had the chance to scratch, he

did—and stumbled into national fame.

LATE IN 1897,

MCCUTCHEON WAS INVITED by a reporter friend, Ed Harden, to go with him as a

guest of the Treasury Department on the round-the-world shake-down cruise of a

new revenue cutter, the McCulloch. They started steaming across the

Atlantic from Philadelphia on January 8, 1898. At Malta, the McCulloch was notified of the sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana’s

harbor on February 15. At Singapore, the McCulloch had occasion to

remember the Maine: the cutter received orders transferring her to the

U.S. Navy and directing her to sail to Hong Kong where Commodore George Dewey

was assembling the elements of the Pacific fleet. On April 25, Congress

declared war on Spain—a war that would last only 113 days but would propel the

United States onto the international stage as a world power.

While

Teddy Roosevelt readied his Rough Riders for a charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba,

Dewey was ordered to steam for another Spanish possession, the Philippines, and

to attack Spanish vessels in Manila Bay. McCutcheon and Harden, as guests of

the Treasury Department, were permitted to accompany the expedition,

transferring to the USS Olympia, Dewey’s flagship. They and a third

member of the McCulloch party, Joseph Stickney, a former editor for the New

York Herald, were the only eye-witness newsmen on hand for the historic

assault on Spanish colonial might in Manila Bay, the only reporters who could

have heard Dewey’s order to Captain Charles Gridley at 5:23 a.m. on May 1: “You

may fire when you are ready, Gridley.”

They

may also have heard Dewey’s other famous order, given after the fifth series of

broadsides crashed into the Spanish fleet—the order to “draw off for

breakfast.” Often cited during Dewey’s aborted run for the White House in 1900

as an example of the commander’s laconic imperturbability under fire, the order

was actually issued because the air was so filled with smoke as to make

accurate firing impossible.

The

three newspaper reporters had a ringside seat for the biggest news event of the

year. McCutcheon took photographs, sketched, and kept a running diary of the

day’s action. Spanish resistance ashore and afloat ceased in a matter of hours,

but since the telegraph cable from Manila to Hong Kong had been cut, the

correspondents couldn’t file their reports of victory until Dewey sent his own

dispatch-bearing boat to Hong Kong four days later.

The

trip took a day-and-a-half, and the newsmen arrived on a Saturday (Friday in

the U.S.). McCutcheon followed the usual practice of foreign correspondents: he

sent a short bulletin at high rates, followed by a longer dispatch at the

cheaper press rates. But Harden, more experienced in such matters, sent his

bulletin “Urgent,” a classification of transmission that cost $9.90 a word

(five times the bulletin rate) and took precedence over all other telegraph

traffic. His bulletin reached his paper, the New York World, before

Dewey’s dispatch reached President McKinley. Harden scooped McCutcheon, but

neither reporter’s paper was the first U.S. newspaper to use their stories.

Both of their papers had gone to press by the time their reports came over the

wire on Saturday (now Sunday in Hong Kong).

Under

the usual news sharing arrangements of the day, the stories were made available

to other newspapers. In New York, the story hit the streets first in Hearst’s Evening

Journal; in Chicago, in the Tribune (which, under Jim Keeley’s

enterprising editorship, put out an extra; Keeley also called President

McKinley, who still hadn’t heard of Dewey’s victory). But McCutcheon’s paper

(now called the Chicago Record) cabled for more details, price no

object, and McCutcheon filed a 4,500-word report (at $2,700) which was the

first long account by any eye witness, and it was picked up and reprinted all

across the country. McCutcheon was famous. Hearst cabled him, offering a job at

any salary he wanted to name. McCutcheon stayed with the Record.

He

also stayed in the Far East. The Record ordered him to sign up cable

correspondents in the region, so after briefly covering the Filipino

Resurrection that ensued in the wake of Manila Bay, McCutcheon scratched his

itch for the next two-and-a-half years, visiting all the places whose names

ring with the romance of far-off climes— Borneo, Bombay, Saigon, Singapore,

Shanghai, Peking, Hong Kong, Afghanistan via the fabled Khyber Pass, Ceylon,

Lahore where he visited the offices of the Civil and Military Gazette at

which Rudyard Kipling first made his reputation, Samarkand, Kashgar, Peshawar,

Znzibar, Madagascar, and the Transvaal of South Africa where he reported on the

Boer War.

In

later years, McCutcheon continued scratching his itch, often in war zones. As Editor

& Publisher reported when he retired in 1946, he hunted big game in

Africa in 1909-10 with Theodore Roosevelt, sending cartoons and articles back

to his paper. He finessed an invitation to go to Vera Cruz and in other parts

of Mexico during the 1914 troubles; he palled around with Richard Harding Davis

and met Pancho Villa and drew his portrait as the Mexican sat, ominously, with

a pistol on the table at which he was posing.

McCutcheon

was still in Mexico when the belligerencies leading to World War I commenced in

Europe. Eager to see the action, McCutcheon left for Chicago where he obtained

correspondent credentials from his paper, drew five memorable war cartoons

(including the famed “The Colors”),  and embarked for England and from there to Belgium,

which the Germans had invaded, officially launching WWI, just ten days prior to

the cartoonist’s arrival in Brussels. With no official papers or specific

assignment, he and Irvin S. Cobb, a 200-plus pound newspaper humorist,

commandeered a taxicab and headed toward Louvain to witness the action. Neither

the U.S. nor Britain were yet officially in the war, so McCutcheon and Cobb

felt they could play the part of innocent correspondents stranded between the

lines. They were soon surrounded by the Germans, who, although declining to make

them prisoners, wouldn’t let them leave the city for two days. and embarked for England and from there to Belgium,

which the Germans had invaded, officially launching WWI, just ten days prior to

the cartoonist’s arrival in Brussels. With no official papers or specific

assignment, he and Irvin S. Cobb, a 200-plus pound newspaper humorist,

commandeered a taxicab and headed toward Louvain to witness the action. Neither

the U.S. nor Britain were yet officially in the war, so McCutcheon and Cobb

felt they could play the part of innocent correspondents stranded between the

lines. They were soon surrounded by the Germans, who, although declining to make

them prisoners, wouldn’t let them leave the city for two days.

When

they got back to Brussels, they learned of the nearly complete destruction of

Louvain by the invaders. McCutcheon and Cobb and two other American

newspapermen were the only on-the-scene reporters during that period of the

war’s beginning. A glutton for war reportage, McCutcheon lurked around long

enough to be detained again by Germans. Released after a couple days, he went

to France and caught a ride with a French plane flying over the German lines

while a German Taube machine-gunned him from above. He made two other trips to

Europe during the war, witnessing on one of them the “great Serbian retreat” of

1915.

McCutcheon

rode horseback through Persia and Chinese Turkestan, ventured into the jungles

of New Guinea, explored the Gobi Desert in a motor car, and made two airplane

trips to South America. Said Starrett: “He has witnessed every war since the

Spanish complication of 1898, including the Russo-Japanese War, which he looked

in on for four days before the Japanese invited him to leave.”

BUT ALL THAT

LAY IN THE FUTURE. For almost three years after Dewey’s triumph at Manila Bay,

McCutcheon was trekking around the far side of the globe. He was gone from

Chicago so long that the girl he left behind decided he’d rather travel than

marry so she wed another. When he returned at last to Chicago, McCutcheon

settled his debt to George Ade by supplying him with material for his first

operetta, “The Sultan of Sulu.” (About this time, McCutcheon’s older brother,

George Barr, published his first novel, Graustark.)

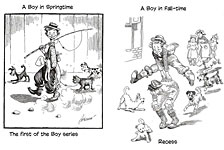

Once

settled again behind his drawing board at what was now the Record-Herald,

McCutcheon began to pioneer a new kind of cartoon. One day in the spring of

1902, seeking to revive the kind of reader interest that his nonfunctional

little dog had inspired, McCutcheon put into his front-page slot a picture of

the kind of boy he (and thousands of others) had been in Midwest’s recently

concluded century—a barefoot kid in straw hat and patched pants, going fishing.

With the dog under his arm. McCutcheon entitled the cartoon “A Boy in

Springtime.” It was an unusual cartoon: neither topical nor political, it was

purely a matter of human interest. When it provoked comment among readers,

McCutcheon provided encores in a series of “Boy” cartoons that depicted

youthful male activities throughout the seasons.

In

another popular series of cartoons that year, McCutcheon reported on the

American tour of Prince Henry of Prussia, depicting in elaborate and

recognizable detail the landmarks and incidents of the dignitary’s progress

through several cities.

The

next year, 1903, Jim Keeley successfully wooed McCutcheon to the Chicago

Tribune. McCutcheon was extraordinarily loyal to the Record-Herald and gave Lawson a chance to match the Tribune’s offer. At first, Lawson

did. But Keeley came along a little later with another, higher, offer. This

time, Lawson couldn’t match it. Nor could he accept McCutcheon’s astonishing

offer to stay for $100 a week less than the Tribune’s bid:

even that was more than anyone else on the Record-Herald was making.

McCutcheon went to the Tribune, taking his “Boy” and the dog with him,

and he stayed there doing front-page cartoons until he retired in 1946.

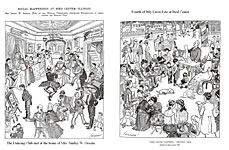

McCutcheon

also took with him another human interest series he’d begun at Lawson’s paper:

“One very dull day, when ideas were scarcer than hen’s teeth,” he wrote later,

“I found myself in desperation for a subject. As a final resort, I drew a

picture of a church social such as I had known in the early Indiana days. I

called it ‘Bird Center.’” Prompted by favorable reader reaction, McCutcheon

drew a second in the series the next week and accompanied it with a text article

of social notes and comments as if it were a news item in a small town

newspaper.

|

|

McCutcheon

began introducing familiar types of characters into these cartoons—the minister

and his wife and numerous children, the local doctor, the judge, the town

drunk, the Civil War vet, a tintype artist—and before long, a slender plot

developed. “Nothing very dramatic, but there were little love affairs and

little ambitions that were gradually unfolded as the series advanced. Each

drawing represented some small-town gaiety. One week the good people of Bird

Center were observing the Fourth of July. The next week, they were having a

baby show. Then they were all picnicking in the woods.”

The

cartoons were eventually published in book form. In the introduction to the

book, McCutcheon explained his purpose in drawing the series. “It was to show

how very cheerful and optimistic life may be in a small town. If it seemed to

satirize some forms of gaiety in the smaller communities, or to poke a little

good-natured fun at some of the ornate pretensions of the society in larger

communities, so much the better, for then the cartoons might be endowed with a

mission. You will find Bird Centerites in large cities as well as in small

ones, and it is to be regretted that there are not more of them. For they are

all good, generous and genuine people, and their social circle is one to which

anyone gifted with good instincts and decency may enter. The poor are as welcome

as the rich, and the one who would share their pleasures is not required to

show a luxuriant genealogical tree. There are not social feuds or jealousies,

no false pretenses and no striving to be more than one really is. No one feels

himself to be better than his neighbor, and the impulse of generosity and

kindness is common to all.”

These

introductory words could have been McCutcheon’s credo as a cartoonist. Many

years later, he explained himself at greater length: “Broadly speaking, all

cartoons fall into two groups, the serious and the humorous. Each has its

place. I always enjoyed drawing a type of cartoon which might be considered a

sort of pictorial breakfast food. It had the cardinal asset of making the

beginning of the day sunnier. It is safe to say the prairies were not set afire

by these cartoons, yet they had the merit of offending no one. Their excuse lay

in the belief that a happy man is capable of a more constructive day’s work

than a glum one. The diet of daily news is so full of crime, crookedness and

divorce that it is sometimes hard to resist the temptation to become a

muckraker who allows the dark spots to dominate his vision. ... But some

subjects should not be treated lightly. Some evils demand more stinging rebukes

than can be administered with ridicule or good-natured satire. In such cases, a

cartoon must be drawn that is meant to hurt. All the same, I have not liked to

draw that sort of cartoon, and it was invariably with a feeling of regret that

I turned one in for publication. It would seem better to reach out a friendly

pictorial hand to the delinquent than to assail him with criticism and

denunciation.”

It

was clearly against McCutcheon’s nature to draw too many of the hard-hitting

kind of editorial cartoon. In the years of the New Deal when assault tactics

were more in keeping with the Tribune’s editorial stance, the paper

brought in Carey Orr when it needed merciless salvos. McCutcheon’s cartoons

continued to be “a gentle mixture of corn shucks, bombazine, bent-pin

fishhooks, and ‘slippery ellum’ whistles.” Albert Beveridge, a

turn-of-the-century U.S. Senator with whom McCutcheon developed a lasting

friendship, always addressed his letters to the cartoonist “Dear J.J.,” which,

Beveridge explained, stood for “Gentle John.”

But

McCutcheon’s gentility had a canny aspect, too, as he once told Editor &

Publisher: “Very often when a public man is attacked with intense

bitterness, he unintentionally gains the sympathy of readers and the

effectiveness of the newspaper’s attack is thereby weakened . A man can survive

violent attacks but rarely ridicule.”

McCutcheon’s

idea of a balanced week of cartoons, observed Starrett, is four pictures

intended to influence public opinion and two or three intended only to make

readers smile.

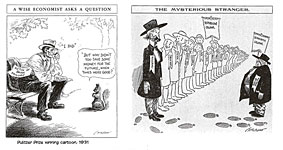

Of

the former variety, Starrett lists McCutcheon’s 1931 Pulitzer-winning cartoon,

“possibly the greatest of them all,” entitled “A Wise Economist Asks a

Question.” Pungent though it is, it also has about it the ordinary aura of the best of

McCutcheon’s homespun down-home efforts. “The Colors,” pictured above, is

undoubtedly one of the great anti-war cartoons. Starrett also remembers “the

terrible drawing that blasted the plan to reopen the Iroquois Theatre after the

fire that too more than six hundred lives. ‘Matinee in the Charnel House,’ I

believe the caption read.”

Pungent though it is, it also has about it the ordinary aura of the best of

McCutcheon’s homespun down-home efforts. “The Colors,” pictured above, is

undoubtedly one of the great anti-war cartoons. Starrett also remembers “the

terrible drawing that blasted the plan to reopen the Iroquois Theatre after the

fire that too more than six hundred lives. ‘Matinee in the Charnel House,’ I

believe the caption read.”

Another

of McCutcheon’s more poignant creations was called “Mail Call”: it depicted a

lone soldier without mail in a crowd of happy recipients. “A cartoon is worth

at least a thousand words,” wrote the Trib’s Sid Smith. “One reader

wrote 11,384 letters to men in service because of it.”

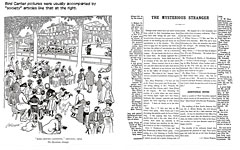

Starrett

calls “The Mysterious Stranger” one of McCutcheon’s masterpieces: it hailed the

entrance of the state of Missouri into Republican ranks during the 1904

presidential campaign, a historic defection from the Solid South that had,

heretofore, belonged entirely to the Democrats. It was entitled, however, not

by the cartoonist but by his editor (who may have had in the back of his mind

one of the Bird Center cartoons that had run the same year; in it, the

mysterious stranger was a vaguely threatening presence).

As

a notable cartoon, “The Mysterious Stranger” has a wholly unremarkable genesis.

McCutcheon had spent a whole day, Starrett said, devising a cartoon that he

thought would provoke much comment and applause, and then his editor phoned him

and told him about Missouri’s defection, saying, “I thought maybe you would

like to use it in your cartoon.”

McCutcheon

was perplexed. He’d just finished a masterpiece of a cartoon, but he realized

it was wise to please his editor. So he hastily drew the cartoon that became

“The Mysterious Stranger”; it took him about half-an-hour. Then he sent both

cartoons over to the editor.

“Next

day,” he said, “I reached eagerly for my paper, expecting to find the

masterpiece on the front page and the Missouri cartoon on the back page or

missing entirely. But the Missouri cartoon was on the front page, and it was

some time before I found the other, back among the election returns.”

The

“Boy” cartoons number among the smile-fostering breed, but the greatest of

these is undoubtedly “Injun Summer,” which was published September 29, 1907.

“That is

a little early for Indian summer,” McCutcheon confessed years later, “but

possibly there had been an early frost that year and a semblance of autumn

haziness; or maybe I was absolutely stuck for an idea and had to use the first

one that came along. Such things do happen. The cartoon was born in a brief

period of tranquillity between wars, and I like to think of it as a symbol of

peace and plenty.”

The

two drawings that make up the cartoon are accompanied by a “lengthy discourse

with the plain-spoken charm of Mark Twain,” wrote Sid Smith a few years ago in

the Chicago Tribune. “McCutcheon’s astute folk poetry captured the sere,

prickly, enigmatic mood of nature’s most puzzling season” as well as a mood of

peace and plenty. (We’ve broken the cartoon into two fragments above in the

hope that the text between the pictures is readable; if not, click on Page at

the top of the screen, scroll down to Zoom, then enlarge the picture by

clicking on 150%.)

The

nostalgic vista in which a farm boy’s imagination turns a cornfield at dusk

into an Indian encampment came right out of McCutcheon’s childhood. Picturing a

shared and mythic past, it struck such a resonant chord among the Trib’s readers

that, starting in 1912, the paper reprinted it every year during Indian summer

season. Until 1993. It last appeared the previous year on October 25. Said

Smith in remarking the passing of the tradition: “The drawings may be timeless,

but the text had outlived its day. Complaints had been voiced for several years

about its offensiveness to Native Americans. Wisps of smoke have continued to

rise from those smoldering leaves, however; every fall, some readers complain

that they miss it.”

McCutcheon

was also a gifted writer. He remained in the Philippines after the Manila Bay

adventure and reported on the subsequent Filipino Insurrection. His report “The

Battle in Tilad Pass” was valued by the Daily News’ managing editor,

Charles H. Dennis, as “the finest piece of war reporting that he had known.”

His four-paneled “The Colors” illustrates the four lines of his poem:

Gold

and green are the fields in peace,

Red

are the fields in war,

Black

are the fields when the cannons cease

And

white forevermore.

Cryptic on

their own, these lines become poignant and powerful when coupled to his

pictures which take us, line by line, from a harvest of peaceful plenty, to

dead soldiers, to mourners, to, finally, the white gravestones that mark where

the soldiers have fallen.

But

the piece I like the best (not that I’ve seen all of the McCutcheon oeuvre) is

called “The Ballad of Beautiful Words,” which consists of nothing but lists or

words that McCutcheon groups in rhyming stanzas.The poem is accompanied by a couple of

illustrations; to read the words, click on Page/Zoom/150%. Here is the first

stanza: But

the piece I like the best (not that I’ve seen all of the McCutcheon oeuvre) is

called “The Ballad of Beautiful Words,” which consists of nothing but lists or

words that McCutcheon groups in rhyming stanzas.The poem is accompanied by a couple of

illustrations; to read the words, click on Page/Zoom/150%. Here is the first

stanza:

Amethyst,

airy, drifting, dell,

Oriole,

lark, alone,

Columbine,

kestrel, temple, bell,

Madrigal,

calm, condone.

MCCUTCHEON

BECAME one of America’s highest paid cartoonists, and he supplemented his pay

with freelance work. But he was not much tempted by money. In the late

twenties, he turned down a chance to make $100,000 a week for drawing two

cartoons every week to advertise cigarettes. He refused the offer, he

explained, partly because he didn’t smoke cigarettes himself (he preferred

cigars) and partly because he was uneasy drawing for advertising.

On

April 1, 1910, Robert W. Paterson, editor of the Chicago Tribune and

son-in-law of the lately deceased founder Joseph Medill, died, and the

management of the paper fell, briefly, on the shoulders of Paterson’s nephew,

Medill McCormick, who quickly proved to be not quite up to the task and

retired, first, into a sanitarium for his health and then into politics,

leaving the paper to his younger brother, Robert “Bertie” McCormick. Bertie

masterminded the transition from one generation to the next, recruiting as his

partner his cousin, Joseph Medill Patterson, Robert W.’s son. The two could not

have been more unlike: Bertie was aristocratic, “an English gentleman in the

ducal tradition,” says Lloyd Wendt (in Chicago Tribune, his history of

the paper)—shy, aloof, fastidious, his wardrobe supplied by London tailors and

bootmakers; Patterson was a commoner—gregarious, understanding, and wholly

oblivious of his perpetually rumpled attire and “totally at ease with ordinary

people.”

Patterson

had worked on the Trib for a time, but had spent the last several years

as a gentleman farmer and author, writing novels, plays, and tracts that

championed such a range of social and political reform that Patterson decided,

unabashedly, that he was a Socialist. “Plowing is better exercise than polo,”

he said, alluding to one of his cousin’s recreations. Contemplating this duo at

the helm of the Trib, Chicago’s journalistic community sat back to watch

what they were certain would be a loud struggle for control of the paper that

would end with it in shreds. But McCormick and Patterson solved the presumed

conflict of their political views by simply alternating control monthly of the Trib’s editorial pages. And the paper thrived.

Not

surprisingly, McCutcheon liked Patterson better than McCormick. He got along

with Bertie, and McCormick never frustrated the cartoonist or bullied him, but

McCutcheon liked Patterson.

He

got to know Patterson better than most of the Tribune’s employees. Both

went to Europe in 1915 to inspect the embryo war, and the two spent several

months together, sharing a cabin on the ship to France and a hotel room in

Paris. On the trip across the Atlantic, they played dominoes by the hour and

talked. McCutcheon, already long established as the star of the Trib’s front page, learned his boss’s philosophy and generally approved of it.

“He

was intellectually honest,” McCutcheon said. “I could not imagine Joe Patterson

misrepresenting a fact although the truth might be awkward and have unpleasant

consequences.”

In

France, the two indulged a common love of adventure one day at Villacoublay

when the French offered them a chance at flying in one of their new monoplanes.

After three months, Patterson left Paris and returned to Chicago. McCutcheon

was sorry to see him go: the experienced world traveler had found in Patterson

not only a good traveling companion but a friend. “One could not have wished

for a more interesting and companionable shipmate,” he said. “In those days,

Joe never asserted the importance which his position gave him, and it was not

difficult to abandon the relation of employer and employee.”

The

feeling, apparently, was mutual: Patterson often said that McCutcheon was the

only person with whom he really liked to travel. And the two took several trips

together in later years until Patterson moved permanently to New York to direct

the fate of the New York Daily News, which he launched in June 1919.

Curiously, before the Paris trip, McCutcheon heard through a mutual

acquaintance that Patterson was almost afraid to go with him because he liked

him so much, and “he felt certain we would not come back friends. This was his

way of saying that he considered himself very hard to get along with.” For

McCutcheon, that was scarcely the case.

McCutcheon’s

passion for travel led him to finagle an unusual contract with the Trib in later years. It permitted him to take four months leave every year (albeit

only the usual two weeks’ vacation pay). After his marriage in January 1917 (at

the age of 48 to a woman of 23 whom he’d known since her birth), most of his

travel was to a tropical island he purchased in 1917 just north of Nassau in

the Bahamas. He bought the isle site unseen; his first view of it was when he

and his bride, Evelyn nee Shaw, visited the place on their honeymoon.

For

the 32 years of their marriage until he died in 1949, she “had the happiness of

being his secretary as well as his wife,” she said. Over many of those years,

McCutcheon, driven by his wife’s insistence, dictated swaths of an

autobiography. When he died without finishing it, his widow finished it for

him, filling in the gaps in the narrative from his speeches and letters and

“from my own Boswellian notebook.” During the years he worked on it, McCutcheon

called it “the Opus”; published in 1950, it is entitled Drawn from Memory.

The

McCutcheons also had a home in Chicago’s Lake Forest, and it was there, on June

10, 1949, that the cartoonist died, quietly, in his sleep, a revered

practitioner of his craft and an admired and loved man. In the last few years

prior to his retirement in 1946, he had drawn fewer and fewer cartoons, but

until early in 1946, he had produced a cartoon every week for the front page of

the Sunday Tribune.

A

testament to his popularity and the affection Chicagoans felt for him took

place in the 1940s when he was honored at the Tribune’s Music Festival

at Soldiers Field. A crowd of 90,000 people stood and cheered as McCutcheon

rode around the arena in a carriage drawn by white horses. Later, they all saw

his “Injun Summer” brought to live in a realist pageant.

When

McCutcheon died, encomiums flowed.

The Chicago Tribune eulogized: “It’s a great pity that men like John

McCutcheon can’t go on living and working forever for the world never has had

enough of them. John could not have been the cartoonist he was if he had not

been a skillful and ready draftsman, the master of three or four matured

styles. But this was only the beginning of his art. His special excellence lay

in a combination of highly developed sense of irony, a delight in the

ridiculous, a small boy’s curiosity, a big boy’s delight in excitement and

adventure, and an all-pervading warm of personality.”

Others

had been saying as much for years.

In

an appreciation prefacing a 1940 booklet of cartoonists’ commemorations of

McCutcheon’s achievement, O.O. McIntyre, the nation’s most widely syndicated

columnist, wrote: “John T. McCutcheon used his pen for an alpenstock and scaled

the Matterhorn. No cartoonist of his or any other time has so influenced public

thought and clarified it for better thinking about affairs at home and abroad.

The chief duty of a cartoonist is exclusion. He must drive from his mind all

motives but public good. The second is to get an audience and keep faith with

them. McCutcheon has done all that—and a little bit more for good measure.”

Artist/activist

John Sloan wrote: “McCutcheon is an artist whose pen drawings have been a

record of the life of the people of the United States as seen through the eyes

of a kindly, critical, appreciative, and very human spectator of their antics.”

Vincent

Starrett: “His pictures reflect the man. He admires those things which decent

people admire—dash, courage, honesty, honor, feminine virtue—and hates those

things hated by decent people—sham, egoism, conceit, affectation, chicanery.

... His pictures are popular because of the same qualities that make McCutcheon

himself popular. Nobody meeting the man could be insensible to his personal

charm. A sympathetic listener, a modest talker, his graceful and winning

personality have made him one of the first citizens of America.”

At

his retirement, Editor & Publisher observed that “the Encyclopedia

Britannica credits McCutcheon as being the chief exponent of one school of

newspaper art—that in which the ‘homely, quasi-rural setting and characters are

presented somewhat in the manner of the comic strip’—as contrasted with the

other school dealing in starker form of pictorial presentation.”

But

McCutcheon’s cartoons sometimes cut to the quick, as the Trib’s obituary

noted: “By no means all of his cartoons were tender. He was quick to redress a

wrong, but his pen was curative rather than punitive, reflective rather than

battering., laughing rather than sneering. Ministers praised him for using his

talents to see the truthful elements beneath current events.”

Carey

Orr, who followed McCutcheon as the Trib’s editorial cartoonist, wrote

perceptively about his predecessor: “John McCutcheon was the father of the

human interest cartoon. His Bird Center series was perhaps the first to break

way from the Nast and Davenport tradition of dealing almost exclusively and in

the most intense seriousness with political and moral reforms. McCutcheon

brought change of pace. He was the first to throw the slow ball in cartooning,

to draw the human interest picture that was not produced to change votes or to

amend morals but solely to amuse or to sympathize.

“The

reader felt these qualities in McCutcheon’s work. The reader said to himself,

‘This man understands me.’”

A

1903 collection of McCutcheon’s cartoons for the Record-Herald was

prefaced by George Ade, who knew McCutcheon at that time better than anyone—and

was also more engaged in the cartoonist’s perspective than anyone else. Said

Ade:

“Those

who have studied and admired Mr. McCutcheon’s cartoons in the daily press

doubtless have been favorably impressed by two eminent characteristics of his

intent. First, he cartoons public men without grossly insulting them. Second,

he recognizes the very large and important fact that political events do not

fill the entire horizon of the American people. It has not been very many years

since the newspaper cartoon was a savage caricature of some public man who had

been guilty of entertaining tariff opinions that did not agree with the tariff

opinions of the man who controlled the newspaper. The cartoon was supposed to

supplement the efforts of the editorial in which the leaders of the opposition

were termed ‘reptiles.’

“The

first-class, modern newspaper seems to have awakened to the fact that our

mundane existence is not entirely wrapped up in politics. Also, that a man many

disagree with us and still have some of the attributes of humanity. In Mr.

McCutcheon’s cartoons we admire the clever execution, and the gentle humor

which diffuses all of his work, but I dare say that more than all we admire him

for his considerate treatment of public men and his blessed wisdom in getting

away from the hackneyed political subjects and giving us a few pictures of that

everyday life which is our real interest.”

The Trib’s editorial writer concluded McCutcheon’s obituary with this: “Our

distress at his going is tempered by the knowledge that he lived a full and

happy life, a life spent in the sunshine. He made the sunshine.”

WE CONCLUDE

with a short exhibition of McCutcheon cartoons and drawings. As you wander

through these galleries, notice the variety of graphic styling on display—and

in each style, a consummate mastery.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |