CARTOONING,

COMIX, COMICS, THE CLASSICS, AND THE KITCHEN SINK

Denis

Kitchen, Elder Statesman

“If

the 1960s underground comix movement can be said to have

distinguished elder statespeople, then Kitchen would definitely be

one of them.”

—Michael Dooley in Voice:

AIGA Journal of Design

This

year, 2009, marks the 40th anniversary of the birth of Kitchen Sink Press, the pioneering

publishing company founded in the unlikely wilds of Milwaukee,

Wisconsin, by campus cartoonist Denis Kitchen, who would spend the

next 30 years publishing cutting-edge underground comix and a

pantheon of the medium’s historic creators, including such

legendary innovators as Will Eisner, Harvey

Kurtzman, Milton Caniff, and Al Capp, along the way consecrating the

graphic novel and baptizing an institution to protect the First

Amendment rights of cartoonists, publishers, and retailers. To

recognize and celebrate the occasion of KSP’s debut, we post

here the article about Kitchen and the formative first twenty years

of his enterprise that was published in Cartoonist

PROfiles in March 1993. Based upon an

interview I conducted with him in the spring of 1992, the article has

been extensively augmented by reports of subsequent events and a 1994

interview with Carole Sobocinski, then Kitchen’s assistant

(subsequently a freelance writer), the aforementioned Dooley article

from 2005, and Michael Dean’s exhaustive examination in The

Comics Journal (No. 213, June 1999) of the

collapse of Kitchen Sink Press in early 1999 as well as the

publication in August 1994 of Kitchen Sink

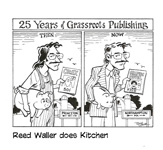

Press: The First 25 Years by the

editor-in-chief of KSP for many years, Dave Schreiner, who died too

young of Crohn’s disease and cancer at the mere age of 56.

Before we plunge ahead, I should warn you that Kitchen has acted as

my agent—or is acting as my agent—to find a publisher for

one of my as yet unpublished tomes. We haven’t had much success

at that yet, but then I haven’t actually written the book

either, so no damage has ensued at either extremity of the

relationship. Mutually blameless, we seem, still, to like each other,

and that’s by far more important in the Great Scheme of Things

than the publication of books of dubious import.

*****

IN

ORDER TO SEE HIS CARTOONS IN PRINT, Denis Kitchen published his own

comic book. That was forty years ago. Almost at once, Kitchen was

immersed in what became, soon enough, one of the

nation’s leading publishing houses for comics and

comics-related materials; almost from the beginning, he no longer

had time to draw cartoons.

Since he started publishing under the Kitchen Sink banner in 1969, Kitchen has co-founded three weekly newspapers and operated a comic strip syndicate (drawing a weekly strip himself), a retail store, a greeting card business, a candy company and a national distribution service—all while publishing underground comic books, “comix” in the parlance of the cognoscenti. In the years of its peak production, his company also published classic and contemporary comics in books and magazines, and it produced trading cards and nostalgic souvenir metal signs, posters, cloisonne pins, art prints, statuettes, and T-shirts and other articles of clothing—all carrying images from the world of cartooning, all produced from a small re-purposed farm with a picaresque address, No. 2 Swamp Road, near Princeton, Wisconsin, where Kitchen had moved in January 1973. “KSP was a virtual artists’ commune,” Michael Dean wrote, “with publishing facilities and living quarters for creators in a restored barn and three adjacent cottages. Kitchen described it as a ‘hippie condominium.’”

By the early 1990s, Kitchen had long established himself as a crusading comics publisher, a champion of creator’s rights fostered by a scrupulously maintained internal royalties system. For a brief time soon after moving into the barn, Kitchen edited a magazine for Marvel, imposing on the funnybook giant a more finely attuned sense of what rights creators have to their work. In the same reformer spirit that inspires iconoclastic comix, in 1969, with only one issue of Mom’s Homemade Comics to his credit, he had run for lieutenant governor of Wisconsin on the Socialist ticket. And then in 1986, combining all the impulses that had driven his life and work, Kitchen founded the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. But always, he remained a cartoonist and a passionate fan and promoter of cartooning.

Kitchen started cartooning in the first grade, he told Sobocinski. By the sixth grade, he was producing a hand-lettered and drawn classroom newsletter that he rented to his classmates for a few cents a view. “It sounds silly,” Kitchen said, “but actually knowing that classmates would pay me to look at something I did gave me a great feeling of power. And I guess that was technically the beginning of my publishing instincts although I never consciously thought of becoming a publisher.”

By the eighth grade, he had achieved mechanical publication with the school secretary’s ditto machine and was selling copies for a dime, then a quarter. “The paper was called Klepto,” Kitchen said, “because somebody stole a couple of the one-of-a-kind [hand-lettered] issues from me, and I accused them of being kleptomaniacs. That’s how the name evolved.” Klepto’s circulation, he claimed, ultimately reached three or four hundred.

The seeds of the Kitchen Sink publishing empire took root at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee where Kitchen earned a degree in journalism. "In 1967, I co-founded the first humor magazine at UWM," Kitchen told me. "It was called Snide, and it lasted only one issue. I was art director, and I was to have taken over the magazine in my senior year, but the editor ran off to Mexico with our profits, so there was no second issue. The second issue was to have been a comic book issue, and that idea never left my mind."

It was still in his mind in 1969 when he returned to civilian life in his hometown Milwaukee after a brief 1968 postgraduate course in the U.S. Army, which he escaped after only 22 days by starving himself into a seriously underweight condition, easily perceived by even army doctors as making him unfit for combat. He quickly became a bohemian denizen of the furloughing enclave of would-be and had-been students on the fringes of the college campus, frequenting the local head shops and counterculture boutiques, where he came across copies of Zap Comix and Bijou Funnies and other graphic evidences of the burgeoning underground and was inspired thereby.

"My dream was to become a cartoonist," Kitchen said, "and I devoted myself to that for the next several months." He produced a comic book, Mom's Homemade Comics No.1 ("Straight from the Kitchen to You"), and talked a printer into manufacturing the book on credit: the print run of 4,000 was determined by how much credit the printer extended.

Having published a

comic book, Kitchen was unexpectedly confronted by the next hurdle:

selling it. He took it around himself to neighborhood book stores in

Milwaukee, head shops, corner drug stores—everywhere he could

think of, including the annual July Fourth Schlitz Circus Parade in

downtown Milwaukee. Hawking copies of Mom’s along the parade route, Kitchen and his cohorts (his younger brother

Jim and his roommate, Bill Kauth) were spotted by the local

gendarmes, who, upon inspecting a copy of Mom’s and viewing one of the cartoonist’s nudes endowed with a

balloon-like chest, encouraged the publisher to make himself scarce.

He did. But he managed to sell all but 500 copies of Mom’s; these he sent with Kauth to Gary Arlington's

San Francisco Comic Book Store. They promptly sold out, and

Arlington asked for more. "That's when I decided to get serious

about it," Kitchen said. "The comic was something I wanted

to do, and I needed to be convinced that I could make a living from

it. I was single at the time and had very low overhead, so I could

take a chance."

*****

THE TIMES WERE RIGHT. In 1969, the counter-culture "underground" was seething with creative energy. Alternative newspapers and comics of all kinds sprouted up in big cities hither and yon (though chiefly in San Francisco and New York). "There was a subculture hungry for its own literature," Kitchen said.

Intending to concentrate his efforts on the creative rather than the business side of comic book production, he struck a bargain with the Print Mint in San Francisco: he would produce the comic book, and the Print Mint would publish it, coordinating the printing and distribution and sales. Accordingly, Mom's No. 1 was revised and reprinted. But Kitchen was not happy with the Print Mint; he decided to become his own publisher again. By this time, he had come to know Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson, two Chicago underground cartoonists. They had published Bijou Comics with Print Mint and were also unhappy. As Kitchen recalled: "When I told Jay I was going to self-publish, he said, Why don't you take Bijou also since you seem to be doing a pretty good job of hustling.”

"That was a very critical moment," Kitchen went on. "I remember not really thinking about the repercussions of that remark. Jay was a friend, and it seemed like a good idea to me. And I remember my answer was, Sure—it's just as easy to do two as to do one, no problem."

Kitchen smiled. "At that moment," he went on, "little did I know, but I became a publisher. I took it seriously. I paid a lot of attention to not only getting my own work published but to taking care of theirs. And that meant expanding our base from a strictly regional one to a national one. I had to hustle more than ever."

He tapped into the burgeoning head shop distribution network that marketed drug paraphernalia (bongs, papers, roach holders, etc.), T-shirts, and how-to-grow-marijuana tracts. The anti-establishment attitude of underground comix fit right into the vaguely outlaw atmosphere of the network and the counter-culture it served. Comix flourished, and Kitchen Sink prospered.

"Our big break came in 1970 when Robert Crumb was passing through town," Kitchen recalled. "He took a liking to me and our operation, and he promised his next book to me. That was Homegrown Funnies, our all-time best-seller. Over 160,000 copies sold over the next thirty years."

Comix gained notoriety for the sexual and drug-culture content of some of the titles, but not all comix were so libidinous or hallucinogenic. The commonest thread in comix was the iconoclastic, taboo-shattering attitude of the cartoonists. But comix are otherwise solidly in the tradition of cartooning, combining words and pictures to tell stories. "We were a logical metamorphosis of the art form," Kitchen said.

“Comics are referred to as art of the masses,” he continued. “If you want to say something to people—to make an artistic statement—I’d think you’d want to reach as many people as possible. Comics allow you to. Comics are an art form. The average person might balk at the statement that cartoonists are artists, but comics are no different than painting or printmaking or any other division of the [visual] arts. Simply, it’s a medium that has its own traditions and tools. The comix I personally did were not by any means pornographic," he went on. "What I was doing was a much softer, gentler kind of humor than my underground compatriots, but it also did not fit into the mainstream. I was not a smut peddler. We simply appealed to an older audience, over eighteen. If a 13-year-old kid picked up our comics, he wouldn’t really appreciate them. I never wanted our books to have sophomoric appeal."

Over the years, Kitchen Sink Press would publish a number of comix safe from sophomoric appeal: Death Rattle, Smile, Snarf, Bizarre Sex, Barefootz Funnies, The Complete Fart and Other Body Emissions, Trina’s Women, Wet Satin: Women’s Erotic Fantasies, Dope Comix, Mondo Snarfo, and Nard ’n’ Pat, to name a few.

Writing about comix in 1971, Kitchen burned with missionary zeal: "The big appeal [of producing comix] is the total freedom involved. No boss. No nine-to-five workday. No restrictions on subject or style. No absolute deadlines. And yet, in this seemingly anarchistic climate, artists who might ordinarily be turning out uninspired work for straight comic companies or ad agencies are developing an innovative genre, with sometimes brilliant results. And, while not united in any particular direction, we are all instinctively dealing with the oppression, injustice, and absurdities we observe—things we feel can't be dealt with in our media by introducing token black characters or by replotting traditional comics so slumlords replace outer-space villains. By ridiculing the outmoded social system we live in, we are quickening its demise. And in its place, hopefully, will be established a society in which no ‘underground’ is necessary."

At the time he wrote this, Kitchen was an active Socialist, having just concluded his predictably unsuccessful campaign for lieutenant governor of Wisconsin. "I was ideologically pure at the time," he told me, "but it's now been about twenty years since I left the party. You'll probably never hear anything as strident as that from me again."

Stridency aside, Kitchen agreed that his 1971 screed captures the essence of the counter-culture politics of the time. "Underground cartoonists certainly felt in many ways that we were part of a revolution," he said. "I don't think we really literally expected some kind of a storm-the-Bastille revolution, but I think we deluded ourselves that the counter-culture movement was going to have significant political impact. In subtle ways, I think it did. Certainly our anti-war stance came to be a majority stance, but at first, we were a small minority.

"Who can say what impact the cartoons had?" he went on. "What was the impact of someone like Robert Crumb or Gilbert Shelton or some of the others in the movement who have been read by millions? Who knows what long-term effects you have? We certainly impacted the comics industry. Artists like John Byrne and Todd McFarlane would not be millionaires today if underground comix hadn't changed the fundamental economic relationship between cartoonists and publishers."

In addition to being paid set fees per page, today's comic book creators usually earn royalties based upon the sales of the comic books they do, share in ancillary income, and retain their original art, and they often own the characters they originate. Forty years ago when the underground began producing comix, none of that was the case. Overground artists and writers were paid a simple flat page-rate no matter how many copies their books sold; and the companies owned all the characters. Kitchen recalled his reaction when he first learned of this situation: "I remember instinctively flinching and saying, That's not right."

It became a generational issue, Kitchen said. "We were the first generation of cartoonists that was aware that Siegel and Shuster had gotten ripped off and that Harvey Kurtzman, we felt, had been ripped off. And we didn't want that to happen to us. We were going to do our damnedest to create an alternative system. If we could make a reasonably decent living and retain our own control, that was preferable to making a good living and working under the old yoke."

Like other underground comix publishers, Kitchen offered cartoonists a share in the profits—royalties—and ownership of their creations. Through the 1970s, the practice was adopted by virtually all of a succession of small publishing companies (the so-called "alternate publishers") that began producing "above ground" comic books during the decade. By the early 1980s, Marvel and DC began to feel the pressure; soon both companies developed policies similar to those first advanced by the underground press.

"There's still a lot of work-for-hire going on," Kitchen said in 1992 when we talked, "some of it unavoidable. If a publishing house owns Spider-Man, for example, you can't really expect them to give the artist the copyright for drawing Spider-Man. However, more and more, when somebody comes to either a big or a small company with a new idea and a new property, they have a much better chance of retaining ownership."

In a blasphemous mood, I wondered whether creator-ownership was an unalloyed blessing: "For years, we have all grumbled about the corporate ownership of characters," I said to Kitchen, "and now there are many artists who own their own characters. And many of these artists who are printed by alternate publishers do one or two issues starring their new characters, and then they never do them again. They either find a more lucrative way of making a living with their art, or they get bored with a character—or something. In any event, they don't continue to do the character they own. The character dies, disappears forever. And that makes me wonder: looking at the other side of the coin, perhaps there is some wisdom in a publisher owning a character. If he does, he can continue a popular character by hiring someone to do the character if the creator tires of the grind. At least, we'd have the character in print. If Superman and Batman hadn't been owned by their publishers, would they have lasted long enough to become the pop culture institutions they are today?"

Kitchen responded at length: "If it's a creator-owned property and the creator chooses to abandon it after a couple of issues, I think that's fine. If a creator creates something that's commercial enough that it could continue indefinitely, perhaps a publisher should administer that property [if the creator chooses not to do it himself]. And that could be arranged. However, in general, it's a positive thing that creators own their own characters. And if they choose, abandon them.

"One of the things we tried to avoid," he continued, referring again to underground cartoonists, "was the curse of success. If we were successful and created something comparable to Blondie, some of us feared the monotony of spending the rest of our lives filling in panels with the same characters day after day after day. That's why someone like Crumb abandoned every character he created that threatened to be successful—like Fritz the Cat or Mr. Natural. Crumb wanted the freedom to draw whatever interested him. The one character that spans his whole career is himself, his autobiographical comics. To take another example, here's Don Simpson who created Megaton Man, got tired of it, and then dropped it to do Border Worlds, and then came back to Megaton Man and then did a slew of other characters. None of them captured the marketplace—though I think Megaton Man could have. But it was Don's choice to kill the character. As his publisher, I was very frustrated because not only did I enjoy the character, but I am in business to make money, and Megaton Man was a commercially successful comic book. When Don abandoned it, I was angry on two counts. I thought it was a foolish career decision. The part of me that champions artist's rights says, Well, of course, he had the right to do that. But as his publisher, I have to confess, it was very frustrating because I think he made a big mistake.

"But I still think it's better for artists to make mistakes and to control the situation," he went on. "I've seen too many instances where the reverse is true and the results are unfortunate. Take one of my favorites—Nancy and Sluggo. I think when Ernie Bushmiller retired, it was a travesty [for the syndicate, the strip’s owner] to allow someone like a Jerry Scott to take those characters, redesign them, and literally get rid of some of the cast. I don't want to knock Jerry Scott; I understand he's a very likeable and talented guy. But I think he should be doing his own strip, and I think Nancy and Sluggo should be allowed to die with their creator. Just as Krazy Kat was unique to George Herriman, so are Nancy and Sluggo unique to Ernie Bushmiller. And I really resent the way syndicates have artificially kept some characters alive and destroyed the integrity of the original strip."

Jerry Scott

subsequently got his own strip—two of them, Zits, which he writes for Jim Borgman to draw, and Baby Blues,

which Scott writes for Rick Kirkman to

draw. Nancy was

re-assigned to Guy and Brad Gilchrist, who restored the characters’

Bushmiller-induced appearance.

*****

KITCHEN’S CITING OF THE SACRILEGE perpetrated on Bushmiller’s creation did not enter the conversation haphazardly: he has long harbored an affection for Nancy and other Bushmillerisms. In The First 25 Years, Jay Lynch recalls his first meeting with Kitchen, which occurred in 1969 after Lynch, accompanied by Robert Crumb, entered Kitchen’s apartment through an entryway “painted with a weird cartoonodelic pyscho-mural [that depicted] all forms of orgiastic activity ... rendered in a style that was strangely reminiscent of—what?” Kitchen offered them beer, “which we drank readily, having heard that was the custom in Milwaukee,” and they talked about comics, and when Kitchen brought out a collection of Nancy comic strips, Lynch said, “It suddenly dawned on us what the influence on the hallway orgy mural was. Bushmiller! Ernie Krunking Bushmiller!”

Kitchen has never entirely evolved beyond his fascination with Bushmiller. He is widely suspected, for instance, of being the power behind the “shadowy cult of personality” that has grown up around Bushmiller (who once referred to himself as “the Lawrence Welk of cartoonists”). An issue of toomuchcoffeeman magazine brought the matter into the open: “A clandestine organization has, for three decades, been associated with the Bushmiller cult: the Bushmiller Society. It has no known headquarters. It has no web site. There’s no information about it anywhere. More and more often, one comes across a Nancy face stuck on the side door of a public toilet or smiling enigmatically at eye level above a urinal. Why? And why Bushmiller? Who is behind the organized weirdness? Most industry fingers point to Denis Kitchen, longtime publisher, cartoonist, and rumored prankster.” After this preamble, Kitchen interviewed himself about his alleged connection to the Bushmiller Society but denied, over and over again, any connection whatsoever.

“Do you head the Bushmiller Society?” he asked himself.

“Let me put it this way,” he answered. “No one knows how to contact Superman directly, but everyone knows you can reach him through Jimmy Olsen. Think of me as the Jimmy Olsen of Nancy fanatics.”

Still denying any direct involvement in the Bushmiller Society, Kitchen explained that he first became aware of it in the early 1970s when “an outfit calling itself the Society of Bushmillerites “ sent him an inquiry about some KSP Nancy merchandise. “I sent a note back pointing out that ‘S.O.B.’ was an unfortunate acronym. The next thing I knew, they changed their name to Bushmiller Society.”

Bushmiller has been admired by many comic strip afficionados for the purity of Nancy: in every instance of the strip, the joke depends upon grasping the subtle relationship between words and pictures. Neither the words nor the pictures make any comedic sense alone without the other; together, the blend into a new hilarious meaning. Bushmiller was said to conjure gags by reading Sears catalogues: he’d turn pages and ponder the things he saw pictured until he could imagine one of those things being the visual punchline of a strip. It was a method that guaranteed Nancy comedy would always depend upon a prop, something pictured as well as something said, the perfect visual/verbal blend.

Interviewing himself, Kitchen talked about the “devotees” of the strip who “see pure Euclidean geometry in Bushmiller’s beautiful and precise art. They apply numerological attributes and elaborate theorems to the characters and compositions.” Some connect Bushmiller’s “texts” to Kabbalah; others see allusions to the psychic Edgar Cayce. “Then there are the ‘Bush Buddhists,’” Kitchen went on, “who sit cross-legged in front of framed Nancy images, generally ‘the three rocks,’ repeating certain mantras taken from the strip.”

Kitchen’s interlocutor became alarmed: “You’re starting to scarce me. What you’re describing sounds like an actual religious sect.”

Kitchen seemed to agree: “We’re considering filing for federal nonprofit status as a 501( c)6 religious organization that will make the Society tax-exempt and —

“We?” said Kitchen.

“This interview

is over,” said Kitchen.

*****

IN HIS PASSION FOR TREATING FAIRLY the cartoonists he published, Kitchen revealed the conscience that made Socialism so attractive to him. Milwaukee, he noted, has a long tradition of Socialist mayors, and his grandfather, a German immigrant, was a Socialist. "So in many respects," Kitchen said, "I was almost born to it. What attracted me to it is that it is, on paper at least, a system that's more fair, and I like to think I'm a fair-minded individual. Socialists have the humanistic attitude that people can cooperate and the world can be improved. That in itself doesn't make Socialism work; there are plenty of misguided do-gooders."

I couldn't resist the obvious question: "Now that you're a mogul with a publishing empire, is there still a Socialist in there, or are you now a capitalist?"

Kitchen smiled (a little ruefully perhaps). "No question," he said, "I'm a capitalist—a small capitalist—by definition. A capitalist with a conscience, I hope, because there are elements of capitalism at its worst that I'm uncomfortable with—but until I get Donald Trump size, I don't think I have to worry about it. My feeling is that the free enterprise system, while hardly perfect, is the best we've got right now. It's been good to me. I've worked very hard over the years, and the free enterprise system can reward someone who works very hard."

The rewards of capitalistic success did not come easy to Kitchen. His business almost collapsed at least twice. In the fall of 1970, when he formed Krupp Comic Works, Inc., around Kitchen Sink Enterprises, he decided that if his competitors were paying royalties of 10%, he'd pay 16%. After a year during which he made no money despite selling products at an entirely respectable rate, he acquired a partner with a more pragmatic business sense. Tyler Lantzy analyzed the operation and announced that the extra 6% was consuming virtually all the company's profits.

"If he hadn't come along," Kitchen said, "chances are that I would have continued to publish with my head in the clouds and would not have lasted. For the next five years or so, he handled the business side of the company and I handled the creative, and the company began to grow."

While publishing comic books under the Kitchen Sink Enterprises label, Krupp Comic Works quickly spawned a mail order business (ultimately out of Boulder, Colorado), a greeting card division, and a retail store called Strictly Uppa Crust. And by the end of the 1980s, Kitchen was also producing Yesteryear, a monthly antique and collectibles paper for Wisconsin and Northern Illinois, and The Fox River Patriot, a twice-monthly feature paper. Kitchen has since divested himself of most of these endeavors, concentrating his efforts on Kitchen Sink Press.

A separate enterprise launched the same year as Krupp/Kitchen Sink was The Bugle, a weekly underground newspaper co-founded by Kitchen and Schreiner, Kitchen’s oldest professional cohort. The two met in college while taking journalism courses. “Sitting side-by-side in Journalism 101,” Kitchen recalled, “we discovered common interests: Carl Barks, Marvel comics, the lame-duck Milwaukee Braves, movies and history. We became close friends.” Schreiner encouraged Kitchen’s cartooning efforts, and when he became assistant editor of the campus newspaper, he commissioned Kitchen to draw a weekly comic strip for the paper. “Buoyed more by his confidence than my own,” Kitchen said, “I produced weekly strips the next three years. When they were good, Dave provided encouragement. When they sucked, he was blunt. He always joked that he was ‘saving the worst ones for future blackmail.’”

At Schreiner’s death, Kitchen wrote about his friend in the Comics Buyer’s Guide: “Dave Schreiner was a class act. Will Eisner showed his ultimate respect by hiring Dave to privately edit (or talk Will out of) every graphic novel he conceived since Dave left KSP’s staff [in about 1993]. As comics grope for literary respectability and bookstore distribution, more Dave Schreiners are urgently needed. On a personal level, Dave was my oldest friend. I miss him dearly. My own life and career would be profoundly different without him. For better or for worse.”

The Bugle was published in Madison, so Kitchen commuted, spending three days there, four days in Milwaukee. Eventually, the itinerant life proved too wearing, and Kitchen stopped working on the paper. (Schreiner stayed with it until it ceased in 1977; eventually, he joined the Kitchen Sink staff, becoming editor-in-chief in 1983.) But while Kitchen was working on the paper, he drew a weekly comic strip and coordinated production of weekly strips for several underground cartoonists who infested the Milwaukee vicinity. In short, he operated a newspaper feature syndicate, which he called, with typical iconoclastic verve, the Krupp Syndicate.

"Some of us had regular characters," he told me. "I didn't, though I think I did some good strips. And it was good for my self-discipline if not for my blood pressure. Our deadline was, I think, Sunday night, and I had a lot of enterprises cooking, so I used to come in Sunday evening, sit down in front of the drawing board, and start sort of tapping the board. The editors would go nuts because they knew the issue had to go to press around midnight. Oftentimes the light bulb wouldn't go off until nine o'clock at night, and then I'd start drawing furiously. Too often, the strip was sent to press with the ink still wet. But I always met the production schedule—if just barely. I often drew Bugle covers, too, and was tapped to illustrate ads. I was never a busier artist."

The Krupp Syndicate ceased operations after two years. It hadn't been a financial success: many of the underground papers that printed the strips had a communal attitude (we reprint your stuff, you reprint ours) and consequently never paid for the strips. But Krupp lived on.

When Krupp Comic Works was incorporated as an umbrella company for Kitchen Sink operations, Kitchen and his cohorts chose the name with a perversely comedic flair. Author William Manchester had just released a history of a centuries-old German munitions and arms manufacturer, The Arms of Krupp, and by invoking that sinister-sounding name, Kitchen doubtless intended to evoke the subversive revolutionary impulse that animated all underground enterprises in those dear old days when storming the Bastille was only another weekend away. The name Krupp expressed a fond hope figuratively: if the German Krupp was a war profiteer, perhaps the American Krupp would prove a war profiteer in the American culture wars But Krupp eventually evolved into something altogether else.

One of the parts of his job that he hated, Kitchen said, was sending rejection letters to young cartoonists who submitted “inappropriate, unprofessional, amateurish or occasionally even psychotic” comics for him to consider publishing. Kitchen escaped this onerous task by inventing “Steve Krupp.” When Kitchen accepted a submission, he signed the correspondence; when he rejected something, Steve Krupp signed the letter. “Before long, Steve also became a character in my own strips,” a somewhat roly-poly sort with menacing blank eyeballs, always attired in a business suit and, sometimes, a derby. “He played the capitalist,” Kitchen explained, “the landlord, the publisher, the distributor—the alter egos I often didn’t want but felt saddled with. I generally portrayed myself in strips as the sensitive artiste while Mr. Krupp was all business, suit-and tie, cigar-chomping, bald, overweight and overbearing. He was the character I loved to hate.”

Kitchen carried his

prank to an unanticipated albeit supremely satisfying extreme.

Sometime in the 1970s, Kitchen was selected by Marquis Who’s

Who to be included in Who’s Who in the

Midwest. After he had returned their

questionnaire, Marquis responded by asking him if he knew anyone

else who he’d recommend for the next edition. Kitchen, feeling

the clutch of a practical joke, recommended Steve Krupp. “When

Steve got a questionnaire,” Kitchen said, “I carefully

filled it out with dumb but believable answers. Steve and I both

appeared in the next year’s edition.” And in subsequent

editions: Kitchen dutifully filled out questionnaires every year for

himself and Steve, giving his fictional alter ego new adventures and

accomplishments every year. For Kitchen, it was, ultimately a

frustrating experience: “Steve qualified to be upgraded to Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in Finance and Industry while my own much duller entry did not pass muster, and I was

dropped altogether from the midwest edition. I no longer fill out

Steve’s forms. He does them himself from his country estate

where he resides with a young dark-haired beauty. I hate him more

than ever.”

*****

THE INITIAL BOOM TIMES OF GROWTH AND EXPANSION for KSP lasted only two or three years, and then the underground comix market collapsed in 1973. Two things contributed to that, Kitchen said: first, the market became glutted with comix, many poorly conceived and produced; second, the Supreme Court delivered a new ruling on obscenity that gave local government the power to determine what was pornographic. The head shops and other outlets for comix feared that they'd be shut down if they carried underground publications, so many permanently dropped comix. Publishers like Kitchen suddenly faced a shrunken marketplace.

About this time, Stan Lee at Marvel Comics made one of his periodic phone calls to Kitchen. Kitchen had been a fan of Marvel Comics all his life, and when he published Mom’s No. 1, he sent a copy to Lee. “I was rather astonished to receive a personal letter back, which was complimentary and funny. And that began some correspondence between us. Then Stan would periodically phone and ask me to work for him, which I never took seriously.” But this time, in the doldrums late in 1973, Kitchen listened. Kitchen didn't want to give up KSP but he knew he had to do something to survive, and he respected much of what Lee had done to revitalize mainstream comic books. "I proposed to him that I would edit a magazine for him that would take the energy of the underground cartoonists and try to plug it into the national distribution system."

But when Kitchen insisted that the contributors to the magazine not be handled on the old work-for-hire basis, Lee protested. Ultimately, they compromised, with Lee giving up more than Kitchen: the cartoonists would retain the rights to characters they had already created, and Marvel would return to them their artwork, at the time a violent departure from Marvel policy. Furthermore, after the third issue, the cartoonists would hold copyright to their work. Coincidentally, the new magazine, The Comix Book, lasted only three issues. (Three Marvel issues; Kitchen Sink printed two more that Kitchen had assembled before the magazine was canceled.)

Lee, Kitchen said, really wanted to tap into this new generation of cartoonists: "He sensed something there that Marvel should be a part of." So, ultimately, he agreed to Kitchen's high-handed proposal. But he remained ambiguous about the project, a feeling revealed in his uncertainty about how he should be credited on the contents page of the magazine.

“On the one hand,” Kitchen explained, “he was concerned that we would be outrageous and embarrass him, so he didn’t want to be listed as publisher or editor-in-chief because then he’d be responsible if parents got upset. At the same time, if the project brought something fresh to Marvel, he wanted to get credit for it. And he couldn’t quite figure out how he could have it both ways. Finally, he phoned me and said, ‘I’ve got it: put me down as the instigator. That way, if they get mad at me, I can say, Oh, well—I just instigated it. And if it’s great, I can say, I instigated it.’”

The first issue came out in late 1974. Kitchen had rounded up work by Kim Deitch, Evert Geradts, Howard Cruse, Ted Richards, John Pound, Trina Robbins, Skip Williamson, and Justin Green, among other less likely candidates, for instance, political cartoonist Bill Sanders. Many underground cartoonists refused to be associated with Marvel, but Kitchen convinced others either to contribute or to allow him to reprint some of their work that had appeared in low-circulation comix. An early version of Art Spiegelman's now-celebrated Maus appeared under the latter dispensation in No. 2.

Kitchen suspects the magazine was killed because it broke ranks with industry custom on artists' rights and thereby seemed to threaten the very foundations of the business. But he is proud of much of the content of the magazine. And despite these bittersweet feelings, he remains grateful to Stan Lee.

"I credit Stan for

having the imagination and the guts to do something that was very

different from what Marvel ordinarily did,” Kitchen said. “And

if it hadn't been for Stan and that experiment, my company would

have gone bankrupt in 1973 or 1974. He subsidized me. He paid me

enough that I didn't have to draw a cent from my own company and

allowed me to stay in Wisconsin. I edited Marvel comics during the

day, and then at night, I moonlighted—I ran my company. And

that's how I pulled through those hard times."

*****

THE MARKET FOR UNDERGROUND COMIX was slowly reviving. It would never be the booming enterprise it had been, but it came back enough to enable Kitchen Sink to continue without the Marvel subsidy. Meanwhile, Kitchen had begun to diversify. He started publishing the reprints of classic comics that eventually accounted for a major share of his business.

A Kitchen Sink catalog circa 1993 offered books that reprinted daily strips from Bushmiller's Nancy, Milton Caniff's Steve Canyon, Ray Gotto's Cotton Woods, V.T. Hamlin's great take on history Alley Oop, and, in full color, Cliff Sterrett's Polly and Her Pals (the marvelous inventive Sundays from the late 1920s), Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon (from the beginning), George Herriman's Komplete Kolor Krazy Kat, and, finally, dailies and color Sundays from Caniff's Terry and the Pirates (the latter two with Rick Marschall’s Remco Books) and, with DC Comics, Superman and Bob Kane's Batman dailies and Sundays. The first of Kitchen Sink's reprint projects, however, was not, strictly speaking, from the pages of newspapers. It was Will Eisner's The Spirit, which had originally been produced as a Sunday supplement for newspapers but in comic-book format.

Kitchen had first encountered this famed creation in the pages of Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! In the early 1970s, Eisner, who had heard about underground comix but was unfamiliar with them, became interested in the operation for its distribution potential and sought out Kitchen during one of Phil Seuling’s comic book conventions in New York in 1972. Eisner proposed a publishing venture that would combine reprints of old Spirit stories with the work of new wave cartoonists, Europeans as well as Americans, and he asked Kitchen to edit the American section.

“Will has always been someone who has been involved in every layer of the business,” Kitchen said, “and he had ideas that he thought could best be expressed through alternative means. He envied the freedom of the underground cartoonists. That was the first thing he expressed to me when we met. He said he would have given anything when he was first starting out to have the kind of freedom we were experiencing. He wanted to be a part of it. I was excited that someone of his generation and status would be attracted to what we were doing. It helped to dispel one of the essential myths of the youth culture.”

Despite Eisner’s professed envy of what he’d heard of the freedom underground artists enjoyed to express themselves in any way they wanted to, his first look at an actual underground comic book almost choked off his enthusiasm: the book he picked up to inspect was one of S. Clay Wilson’s productions, customarily an orgy of raw sex and gory violence (or gory sex and raw violence—it’s hard to tell one from the other in Wilson’s oeuvre).

“He blanched,” Kitchen said, “and I knew the publishing idea was dead. Captain Pissgums and Ruby the Dyke were too much for him. When I got back to Milwaukee, I sent him everything we published to show the wide variety, told him that I’d still like to do something with him, and hoped we could keep in touch.”

When Eisner saw some of the KSP books, he realized that Wilson’s work was not the norm. “He had an attitude that I found very refreshing among his generation at the time,” Kitchen said. “He was a true artist, I felt. He had no preconceptions about what a comic book should be. And while he himself would never draw the things Wilson did, he nevertheless thought it was a healthy sign, that artistic freedom reigned."

Kitchen Sink subsequently published two Spirit books in late 1972 and in 1973, each one combining reprinted stories with a few new pages and covers that Eisner produced for the occasion. These attracted the attention of James Warren, who lured Eisner into his bailiwick with newsstand distribution and put out 16 issues of Spirit reprints. Eisner left Warren in 1977 and returned to Kitchen Sink, which began exclusive publication of his work—not only The Spirit but such new creations as A Life Force, The Building, The Dreamer (an autobiographical treatment of the early days in the comic book industry), and To the Heart of the Storm, an early Eisner exploration of anti-Semitism.

"So at first," I said, "you didn't make a deliberate, calculated decision to reprint classic comics. You just sort of fell into it because you liked Eisner's work."

"Precisely," Kitchen said. "And after that, things happened pretty fast. I had grown up reading comics, and I was interested in history. I don't consider myself a true historian, but I was a student of history. And I thought too many of my seventies contemporaries had this attitude that was summed up by Jerry Rubin—Never trust anyone over thirty. And even when I was in my early twenties, I sensed that was inherently stupid, arrogant and fascistic, and I felt that it was important as cartoonists that we know what preceded us. And so as soon as I realized that Will Eisner was accessible and interested, that opened my eyes to any number of possibilities. Though the Eisner project was an accident—that is, it wasn't premeditated—I realized I could do the same thing with other forerunner cartoonists."

Kitchen's next reprint book was a 1976 collection of some of Harvey Kurtzman's pre-EC comic book work (Hey Look!, Potshot Pete, and Sheldon), a project that lead to Kurtzman's agreeing to let Kitchen Sink reprint all of his work that he controlled—much of it, from original art. Jungle Book, Goodman Beaver, and the complete Hey Look! had been published by the time of our interview, and work on the complete Little Annie Fannie was underway. It was subsequently published in two volumes in 2000 and 2001 by Dark Horse after KSP fell apart, but Kitchen’s editorial work is evident in the essays and annotations in both volumes. The jewel in the crown of the Kitchen Sink reprints, however, is Al Capp's Li'l Abner, which was reprinted in chronological order, one year of daily strips to a volume, at the rate of about four volumes a year. Kitchen intended to publish the entire run of Capp's great strip but reached just 27 volumes (1961) of the projected 43. Four volumes of Sunday Li’l Abner, “The Frazetta Years,” also appeared after KSP’s demise, published, like Little Annie Fannie, by Dark Horse with telltale annotations by Kitchen. "Growing up," Kitchen said, "Li'l Abner was my favorite strip."

Kitchen is usually guided by his personal taste in deciding what to publish, but he always consulted with Schreiner and Peter Poplaski, his designer since almost the beginning.

"Pete is a big Milt Caniff fan," Kitchen said, "and it was at his urging that we started reprinting Steve Canyon. I did not grow up with Steve Canyon, and I don't like the militarist nature of it; but I've come to appreciate the obvious storytelling genius Caniff had, and the strip has grown on me. Pete and Frank Stack convinced me to do Alley Oop; I didn't grow up with that strip either."

Working out of offices in the converted barn, surrounded by antique jukeboxes from the thirties and forties and numerous other odds and endments of pop culture in 20th century America, Kitchen continued to publish the work of contemporary cartoonists, too— Mark Schultz's Cadillacs and Dinosaurs (originally Xenozoic Tales), Reed Waller and Kate Worley's Omaha the Cat Dancer, the award-winning Kings in Disguise graphic novel by James Vance and Dan Burr, the autobiographical Melody by Sylvie Rancourt and Jacques Boivin, James O’Barr’s graphic novel The Crow, which was picked up for an ill-fated motion picture version, and others. And there were fresh issues of comix like Blab, Curse of the Molemen, Buzz, and Grateful Dead Comix. Kitchen Sink brought out an average of 6-8 titles a month—magazines and books—plus the line of comics-related merchandise.

"I like creating

merchandise that's comics related," Kitchen said. "When

you do a metal sign with Betty Boop on it, it's something of

permanence with a cartoon image going to some far-flung corner of

the earth."

*****

DESPITE HIS SUCCESS IN SURVIVING BAD TIMES in order to thrive in the good times, Kitchen almost quit publishing in the 1970s. He became discouraged, he told Sobocinski, that his career had “led in a business direction and not in an artistic direction.” He wanted to get back to the drawing board. That he didn’t is due almost entirely to Harvey Kurtzman.

“I was in New York visiting Kurtzman and Eisner,” he said, “and I told them of my intention. I received advice from each of them which was the opposite of what I expected. I expected Will, who had become a businessman after being an artist, to argue and dissuade me, and, instead, he told me he understood and gave me his blessings. And I expected Harvey, who I considered a ‘pure’ artist, to sympathize and instead he berated me. He said, ‘Good artists are a dime a dozen. We need good publishers.’ I remember he told me, ‘You have a proclivity for this and a lot of us are depending on you. Don’t give up the ship.’

“I remember being very disappointed with Harvey’s advice and, at first, I was determined to ignore it. But the more I thought about it, the more Harvey’s admonishment affected me, and so I plodded on. Had he not told me what he did, I think, for better or worse, I would have gone back to the drawing board.”

Years later, with

another twenty years of publishing high caliber comics and

comics-related material, Kitchen cast an eye back over the history

of KSP and his nefarious career as a publisher: “In

retrospect, the prospects of a publishing company beginning with no

capital were virtually nil,” he told Sobocinski. “And if

I had known anything at all about what it took to publish, to

distribute, to warehouse, to fulfill orders, to acquire new

properties, and all of the other things I would ultimately be doing,

I would have thrown my arms up in despair and said, ‘This is

crazy.’ Fortunately—or unfortunately—no one warned

me how complicated this would all become.”

*****

IN THE MID-1980s, Kitchen launched another project, an odd one, perhaps, for a publisher, but an imminently appropriate one. As the conservative wave washing over the country lifted Ronald Reagan into the White House, it also lapped up against some of the comic book retail stores, threatening not only the owners of the stores but, in a possible chain reaction, the publishing and distribution apparatus that kept them supplied with comix and comics. When Michael Correa, manager of Friendly Frank’s, a comics shop in suburban Chicago, was arrested, tried, and convicted of possession and sale of obscene materials, Kitchen felt the sting of obligation: among the titles deemed obscene were two KSP productions—Bizarre Sex and Omaha the Cat Dancer. As the publisher, Kitchen felt a responsibility to fight for Correa. Kitchen organized a fund-raiser, collected $20,000, and hired an expert First Amendment litigator. When the case reached the appellate court, Correa was acquitted. After paying the legal bills, Kitchen used the few thousand surplus bucks to set up a permanent nonprofit organization to help oppose similar threats to freedom of speech and expression in the future: he established the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) in 1986 and served as its president for the next 18 years.

The CBLDF has come to the aid of several shop operators and comic book publishers in the years since. Some cases have been lost; others have been won. But in every case, Kitchen believes it important to mount a defense. “If we don’t hang together to support the Fund,” he once said, paraphrasing a famous patriotic utterance, “surely we will hang separately.”

In 2005, the year after

Kitchen retired from CBLDF, he received the organization’s

Defender of Liberty award. He spoke afterwards to Michael Dooley:

“Getting good comix created and published is only half the

battle,” Kitchen said. “Getting them into the hands of

customers is always the more complex matter. My concern is that

every case [that threatens comic book shops] makes some retailers

more nervous, particularly those in the Bible Belt, and thus even

more cautious about carrying ‘borderline’ material. It’s

much easier for a retailer to quietly take preventive steps to avoid

being [the next victim] than to be brave and carry the full variety

of material you ideally want your customers to be able to choose

from.”

*****

IN SUMMING UP HIS PUBLISHING PHILOSOPHY—both for reprints and for contemporary comic books—Kitchen said: "I like to think what they all have in common is that they're good. That may sound a little arrogant, but that's what the idea is. I get some heat from some people who are politically left who say, ‘We like underground comix—how can you publish Caniff?’ And the only answer I can give is that I think they're all good comics. And I no longer have a political axe to grind. Call it maturity or political waffling or whatever you want, my feeling is that I can easily rationalize publishing both so-called underground comix and Steve Canyon because ultimately it's the storytelling and the art that I'm looking at. The message is second."

Although he was undeniably a successful publisher, Kitchen is still a cartoonist inside. But very early in his publishing career, he had to cut back on the cartooning he did. As an artist, he was not fast, and the preoccupations of publishing soon crowded out the time he might have had to draw.

"As more artists began bringing their stuff to me," he told me, "I inevitably had less time to draw myself. Drawing is hard work. It's not something I sit down to and the brush flows. I enjoy drawing; I find it relaxing. My main enemy is time. The business I've created is an all-consuming monster. It just eats up all the time I have. So while the idea of drawing a cartoon appeals to me greatly, I have to work very hard at carving out the time for it."

And if he's cartooning for his own company, there's another complication: as publisher, he gives himself so many extensions on deadlines that he never produces the material. He's been assembling a collection of his own work for years, and he's repeatedly assigned the production to a freelance editor who will force him to do a new cover and to pull artwork from the files. So far—as of 2009—that maneuver hasn’t worked. Yet. Although it might. Soon.

In 1992, I asked Kitchen if he had any advice for aspiring cartoonists, and he picked up the thread that runs through his entire career:

"I think it's very important that any young cartoonist do his or her best to retain control over what they do. They should think twice before signing any work-for-hire contracts. It's often necessary to do that—maybe as a stepping stone to one's ultimate goal—and there might be mitigating circumstances, but I think that it's very important that they avoid falling into that trap for their entire career if they can help it. Now obviously you can look at someone like, say Charles Schulz, who does work-for-hire and is a multi-millionaire. And he says, ‘Who cares if United Feature owns the work?' That's why there are mitigating circumstances.

"On the other hand," he continued, "there are a lot of artists I know who would rather make $20,000 a year and control their own work than to work for Marvel and make $200,000 a year. That's just a fact. There's more to life than money. And if you're doing some mindless strip and you're not enjoying it, then maybe the money makes up the difference. But in terms of ultimate satisfaction, if you're attracted to this field because you're an artist, you have to ask yourself what kind of an artist you are. Are you an artist for hire? Or are you an artist?"

"Nicely put," I said. "And it sort of sums up why you got into publishing, doesn't it? That's really the whole story, the theme of your life."

"Yes, it is,"

Kitchen said. "If I were just a businessman looking at all this

pragmatically, I wouldn't have done it at all. I've enjoyed relative

success, but more importantly, I've enjoyed what I'm doing. And the

only reason I'd be a publisher is because I enjoy it. You have to

ask yourself the fundamental question: What gives me satisfaction?

And I've had an argument with myself for the last twenty years. Do I

want to keep publishing or do I want to be an artist? And I draw

enough to satisfy me—or, at least, to prove to myself that I

still can do it. Is it like riding a bicycle? Do you forget how? So

a couple times a year, I have to sit down and do a page or two. I

enjoy it immensely. I feel that if I ever did sell the publishing

company and go back to the drawing board full-time, I might have

regrets and say, Boy—doing this every day is really a chore.

But when I only do it once in a while, I find it enormously

satisfying."

*****

KITCHEN DREW LESS AND LESS. The foregoing article was published in the March 1993 issue of Cartoonist PROfiles, and at the very moment it was being mailed to subscribers, Kitchen and his crew were moving—boxes and boxes of inventory and office furniture and files— to Northampton, Massachusetts, the home office of Tundra, a publishing company founded by Kevin Eastman with his share of the millions his co-creation, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, had showered on him and his partner, Peter Laird. Kitchen Sink Enterprises had attracted the attention of other players in the entertainment world—notably, Mitchell Rubenstein, founder of the Sci-Fi Channel, and at least one other—but of the lot, Eastman’s overture to Kitchen in late 1992 most appealed to him: Eastman was also a cartoonist, and he shared Kitchen’s commitment to First Amendment issues, high production values, and creator’s rights. By March 1993, the two had agreed: Tundra would be absorbed by Kitchen Sink Press with Kitchen and Eastman the two major stockholders. And Kitchen’s company would move from rural Wisconsin to Eastman’s erstwhile cutlery factory in western Massachusetts.

The merger was the brass ring that Kitchen couldn’t help seizing. “I was tired of being a small company in the middle of Wisconsin,” he admitted to Michael Dean when contemplating how the plug had been pulled on Kitchen Sink. “I had practically starved myself for years. I felt I was straining myself in every way. After I got married [in 1980 to his second wife, Holly Brooks; his first wife, Irene, having left him in 1980 with two daughters to raise], I had to worry a little more about money, but for many years, I had operated without a conventional monetary reward. At a certain point, that becomes old.” Dean continued: “So Kitchen chucked his barn and his independence for a chance to join the big publishers on the East Coast with the backing of Eastman’s Turtle money. After moving to Northampton, he said goodbye to his years of deprivation by buying himself a Ferrari and a $400,000 home” into which he moved with his third wife, Stacey, and their baby daughter Alexa.

Kitchen was optimistic about the prospects of the fateful merger with Tundra: “I didn’t think I would have to compromise my values,” he said. “I thought I would be able to publish the same material but on a larger scale. I felt it would benefit the creators and employees, too. It would be in everybody’s interest for KSP to grow.”

Kitchen believed that the merger would give comics a foothold in the “real” bookstores. Shortly after moving to Northampton, he told Sobocinski: “I wanted to break from the bitter stranglehold of superhero comics shops and have the opportunity offered by shelf space in bookstores where literate adults have a chance to pick up our titles and buy them based on their merit. And if we can accomplish that, it will be a major step in the advancement of the medium.” In retrospect, Kitchen admitted to Dean, “the decision to merge with Tundra was the beginning of the end of KSP.” When Dave Schreiner died in 2003 and Kitchen wrote an obituary for him in the Comics Buyer’s Guide (No. 1558, September 26), he re-read some of Schreiner’s predictions about a Kitchen Sink/Tundra merger, which Schreiner had opposed, and realized that Schreiner had proved “downright prescient.” Schreiner did not move to Northampton but continued to edit some of KSP’s classic reprints and other books.

Kitchen may not have realized the extent of Tundra’s financial shambles. Eastman, a comics creator himself, was too solicitous of cartoonists, frequently giving generous advances for artistically superior but commercially unprofitable projects and then not pestering the cartoonists avidly enough to meet production deadlines. And he’d set up expensive branch offices in London and Los Angeles and staged extravagant promotional parties. The Turtle millions were rapidly evaporating, and although the merger was supposed to hitch Kitchen’s disciplined publishing expertise to Tundra’s money, there proved to be not enough money to last as long as it was required. Within a year, Kitchen and Eastman were looking for a bailout from other investors.

The soul-sinking details of the collapse of KSP are exhaustively presented and discussed by Dean, and I won’t review them here; here, I want to celebrate Kitchen’s achievements not conduct a wake. Suffice it to say that KSP went through another couple of investor relationships that soured, one after another, and by the end of 1998, Kitchen had thrown in the towel, the washcloth, a bar of soap, and all the plumbing: Kitchen Sink Press shut down. It didn’t declare bankruptcy: the assets of the company were simply liquidated in the expectation that creditors would be paid. Perhaps most were, but many cartoonists weren’t. It was out of Kitchen’s hands: the ownership of the company had passed to one of the investors, who had effectively elbowed Kitchen out of his own company. “It was,” Kitchen said, “an ignominious end to a 30-year run.”

But there was much to praise in the quantity of quality material KSP had published in those three decades—reprint collections that preserve classic vintage comics by some of the profession’s giants and new books by emerging comics masters. In his 1994 interview with Sobocinski, Kitchen said he was proud of having provided “an uncensored forum for many of the best alternative cartoonists, allowing artists to create comics in unpopular and controversial areras such as the gay comics, sexually explicit comics, or political comics.” Not to mention lot of fun byproducts, posters, buttons, and the Bushmiller Society. Much to be proud of. Kitchen also expressed regret on a few matters when the Comics Buyer’s Guide interviewed him, post-KSP.

“On the bad move side,” he said, “I’d have to list saying ‘No’ to Phil Seuling when he offered me a piece of his crazy idea to directly distribute comic books [to retail outlets, a maneuver that effectively revived the comic book industry]. I also had the first opportunity to be the publisher for Chris Ware, Chester Brown, and certain other terrific artists over the years and didn’t move fast enough. I have plenty of missed opportunities to kick myself for. But then, Will Eisner reminds me that he turned down Superman in the thirties, so hindsight is always easy.”

Kitchen Sink may have gone down its own drain, but Kitchen himself is hardly finished.

That he would somehow survive I never doubted. At a cocktail party a few years ago, I watched him in action. I’d come with a friend who had some comics-related project in mind, and when Denis heard what it was, he quickly, without batting an eyelash or pausing to think, outlined a series of steps my friend should take in order to achieve the desired outcome. Kitchen’s plan was solid, firmly based on the realities (and secret aspirations) of the comics industry, and revealed his consummate understanding of the industry and its marketplace. It was an understanding he quickly put to the test in his own life after the dissolution of KSP.

Hunkering down in western Massachusetts, he established the Denis Kitchen Publishing Company that markets books, collector’s cards, buttons and such like; and the Denis Kitchen Art Agency that represents the estates of Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, and Al Capp among others. He’s a partner in two literary agencies, with John Lind and Judith Hansen respectively, placing and shepherding book projects into print. And he’s co-authored two books recently for Abrams/ComicArts: Underground Classics (an exhibition catalog) and the extraordinary Art of Harvey Kurtzman. And then there’s the prodigy cartooning daughter of his third marriage, Alexa, whose work Kitchen has published and who, not yet ten years of age, has already won awards for her efforts.

It’s enough to keep a man busy. Some years ago, Kitchen said: “I got sucked into this business because I couldn’t draw fast enough to support my family.” He still can’t. His failure to produce much artwork is a running joke in the rare cartoon he manages to draw these days. But he still enjoys doing it. “Every time I daw, I love the experience,” he told Michael Dooley in that 2005 interview, “and I wish I could do more, but my other hats reliably cover the overhead. Consequently, they take precedence. And thus cartooning runs a distant sixth among my professions.”

Perhaps we’ll eventually see some of Kitchen’s cartooning again. This year we may see Dark Horse’s “surprisingly large and overdue collection, The Oddly Compelling Art of lDenis Kitchen.” Maybe. Then again, Kitchen the cartoonist has always had trouble meeting the publisher’s deadlines. And this book was originally scheduled for release in 1989.

We’ll see. And just so you’ll have some notion of what is forthcoming, here’s a Gallery of Kitchen Art.

|

|

|

|

|

|