FRANK CHO AND THE ART OF LIBERTY MEADOWS

A History and Appreciation

|

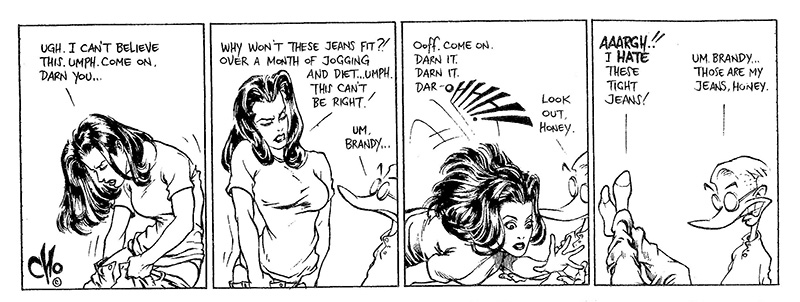

WHEN I FIRST SAW BRANDY, the toothsome heroine of the syndicated comic strip Liberty Meadows, trying to get into Frank’s pants, I knew I was in the presence of a veritable genius of the visual medium. Now, in order to avoid perpetrating any more confusion than I already have with just one sentence, I should point out that Frank wasn’t wearing his pants at the time Brandy was trying to get into them. No, Brandy (who was admittedly living in sin with Frank at the time) had merely picked up a pair of his pants thinking they were hers and tried to put them on, but she had too generous an allowance of embonpoint to fit easily into Frank’s jeans. So her effort was something of a struggle. And, given Brandy’s curves, it was an attractive struggle, one that I enjoyed witnessing.

Oh, before I forget, one or two more not entirely incidental details—Frank, in the preceding paragraph, is Frank the Duck, not Frank Cho, master draftsman, cartoonist extraordinaire and creator of Frank the Duck (and of Brandy). Frank the Duck came before Frank the Vet, the epic-size loser who is one of the populace in Liberty Meadows. (I’d say he’s the central figure in Liberty Meadows except that it’s pretty obvious that Brandy’s is the central figure in Liberty Meadows.) Frank the Duck, on the other hand, is incontestably the hero of University2 (“University Squared”), the comic strip Frank Cho did for the campus newspaper while studying to be a nurse at the University of Maryland, 1993-96.

Frank the Duck is the hero because he got the girl—Brandy (with whom, as I said, he was living in sin, and if sinning with Brandy doesn’t make you heroic, nothing will). Liberty Meadows, the comic strip nationally distributed by Creators Syndicate, is the civilian version of University2, and it might help in understanding Liberty Meadows if you know something about University2. But before I get to that, let me prolong the suspense by regaling you with just a tad more on the subject of Liberty Meadows in case you’ve never seen or heard of this attractively rendered, outrageously funny comic strip.

Liberty

Meadows is the setting as well as the title of the strip. Liberty Meadows is a

wildlife preserve and animal shelter. The strip’s cast is both animal and

human. Brandy is an animal psychologist, but she’s not an animal: she’s an

absolutely gorgeous edition of humanity's curvaceous gender.  Frank, as aforementioned, is a

vet. And he’s also human (only too human, as it turns out). Then there’s the

shelter’s chief administrator, Julius. The last of a quartet of humans is Tony,

who is the all-purpose handyman and errand-runner.

Frank, as aforementioned, is a

vet. And he’s also human (only too human, as it turns out). Then there’s the

shelter’s chief administrator, Julius. The last of a quartet of humans is Tony,

who is the all-purpose handyman and errand-runner.

The rest of the strip's inhabitants are four-legged or beaked. And (here's the wonderful part) they all talk to one another. Animals and people. Without the slightest inhibition. They occupy the same planet, the same meadow, so they live together and talk among themselves—absolutely unabashed—sharing views and adventures in complete disregard for the disparity in their species.

This surreal harmony is never explained. Cho has the storytelling sense to know that an explanation would destroy the essential ambiance of the world he has created. Instead, we are asked to accept this marvelous fantasy without question, without quibble. And we do.

We do, I think, because Cho gives us no choice. He draws people more-or-less realistically; he draws animals as cartoon characters. Immediately upon seeing this ensemble, we know it's impossible. Knowing it's impossible, we also know there's nothing to be gained by questioning it: we may as well accept it. All of Cho's characters accept it; so, too, should we. We join the cast. We participate in the harmonies of life.

Now, for my promised digression on University2.

Set on a college campus, University2 had an animal component consisting of a motley collection of experimental animals (and one vegetable), who, lost in a shipment to the college laboratories, discover that an obscure politically correct regulation dictates equal rights on campus for all its occupants. So they enroll as students—tuition paid for by the state. Then the madness begins.

They all pledge a fraternity, which, judging from the behavior of its denizens, might have been the inspiration for Animal House. Cho's anthropomorphic ensemble included Dean the pig, Ralph the hostile gerbil, Leslie the lima bean, and, finally, Frank, a duck. The antics of Dean (who is a particular kind of pig, a male chauvinist pig) and Ralph and Leslie are hilarious in a no-holds-barred, unrepentant fratboy fashion. But Frank the Duck gets to your heart.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frank falls in love with the most beautiful co-ed on campus, Brandy. Before long, they are living together in romantic bliss. And so persuasive is Cho's treatment—in both story and art—that we not only accept this unconventional pairing: we hope for their happiness ever after. A few choice fragments of their life together had been published in a 1996 Chicago ComiCon booklet—the strips showing Brandy’s struggle—and that’s where I met them, Brandy and Frank the Duck.

Most of the characters made the transition from University2 to Liberty Meadows without losing any of their vital comedic personalities. Except Frank. Frank got transmogrified into a human. And he no longer got the girl. Frank the Vet wants the girl—he lusts after her with every hormone in his body—but he’s so intimidated by her Homeric beauty that he can’t even ask her for a date. This makes him much funnier than Frank the Duck so his transformation might be a good thing.

|

|

|

Syndicate officials objected to Frank the Duck because (they are alleged to have said) “you can’t have a duck in a family newspaper having an intimate relationship with a woman.” I, as you doubtless have by now surmised, had no trouble at all with Frank being a duck and being intimately involved with Brandy. Live and let live, I say. But I’m not a family newspaper.

Presumably, family newspapers would have trouble with gerbils and sentient lima beans, too, so Cho mutated Ralph into a midget bear (formerly with a circus) and Leslie into a giant frog. And by way of ringing in a substitute for the Duck that was Frank, he introduced a new character, Truman, a duckling. But these changes were not the first of the life-altering experiences Cho has had to adapt to.

|

|

|

BORN IN SEOUL, KOREA, in 1971, he came to this country at the age of seven and was immediately laughed at. His actual Korean name is “Duk,” which is pronounced “duck,” so in school whenever his teachers called roll, his classmates would be inspired to blurt out an insane chorus of “quack, quack, quack.”

In high school, Cho attempted to instruct his fellow scholars in the subtleties of his names by doing a comic strip for the school paper in which he himself appeared as a duck named Frank. This probably didn’t convince anyone of anything, so he continued the same propaganda campaign while he attended Prince George’s Community College, 1990-93, perpetuating his highschool comic strip, Everything But the Kitchen Sink, in which he introduced a gerbil, a lima bean, and a pig (who was named “Ragamuffin” at first).

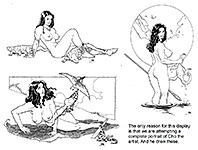

And when he went to the Maryland School of Nursing in 1993—a career choice influenced chiefly by his belief that his chances of scoring with the opposing sex would improve in an educational environment where the gender odds were greatly in his favor (eight-to-one, in fact)—he took the entire ensemble with him. Including his alter ego, Frank the Duck, who, as I’ve already pointed out, got lucky with Brandy, thereby enacting Cho’s own hopes for himself. (Brandy, like Frank the Duck, is drawn from the cartoonist’s own life: she is a composite of several young women Cho admired as a youth, including Linda Carter, tv’s Wonder Woman.)

But of the changes Cho was required to make to his collegiate opus in order to adapt it to family life on a national scale, none was more anguishing than the surgery he had to perform upon the magnificent figure of his heroine. Syndicate officials expected the strip to appeal to young mothers with small children (as well as to Generation-X readers and with-it adults who enjoy the strip’s cerebral patina), and they realized that the pictures of cute animals would attract the attention of those youngsters. These young mothers, syndicate officials reasoned, would have no trouble explaining to their offspring the talking animals, but they would probably have difficulty explaining the size of Brandy’s bosom.

Why this should be so, I haven’t a clue. Young children are, presumably, familiar with the female bosom, having encountered it in its maternal manifestation virtually at birth. (Even mothers who resort to bottle feeding have been known to clutch their babies to their bosoms in a frenzy of affection.) But our culture is peculiar and illogical on this subject—has been ever since Playboy introduced it to bosoms about fifty years ago—and we’re stuck with our culture. Brandy was simply too zaftig, and so Cho de-zaftigged her somewhat before the strip was launched into national distribution, debuting in newspapers on March 31, 1997.

|

|

|

Secretly, however, he resolved not to leave her bust alone. He continued fondling—that is, re-touching— it (which implies, by irrefutable verbal logic, a certain amount of touching before re-touching can occur). Slowly, month after month, Cho increased her measurements until, after about three years, Brandy’s front was back in all its glory.

Well, nearly.

Cho

learned to drawn the female bosom as a single protuberance—exactly as it

appears in reality when clothed: a sort of shelf of flesh hanging from the

clavicle. The problem with his earlier renditions was two-fold—to wit, the

accentuation of the bosom as individual breasts, an emphasis that was achieved

by studious graphic application of stretch lines that showed the strain the

fabric was under in confining these natural wonders. Cho simply eliminated the

stretch lines (an operation much of womankind would doubtless appreciate if it

could be achieved on a wholesale basis for the entire sex; but I’m just

guessing). Without evidence of any stretching cloth, Brandy’s bosom was

singular not plural and could therefore be any desired size. And so it is.

Desired, I mean.

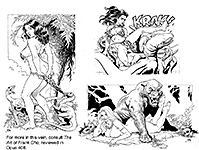

Otherwise, Cho continued to demonstrate his mastery of a variety of drawing techniques in the comic strip—inspired by such classical penmen as Franklin Booth, Joseph Clement Coll, and Howard Pyle as well as the more contemporary Don Newton, Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, and Al Capp not to mention Berk Breathed’s Bloom County and Cho’s preoccupation with the 1933 King Kong movie and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan.

Liberty Meadows is a showcase of Cho’s consumate drawing ability. He can draw anything. He can draw anatomically convincing humans (especially the rounded kind but not limited thereto), gorillas, and any other critter as well as any prop, locale, or background detail. He can render faces and figures from any conceivable angle, and never does the picture seem strained or awkward in the slightest.

And his linework is sure, confident. The lines are clean, uncluttered, boldly assertive. There is nothing hesitant about them: Cho knows precisely where to put every line to do its job. And line is the index of all drawing, the vital ingredient, perhaps the whole show. The purity of Cho’s line shows us what drawing is.

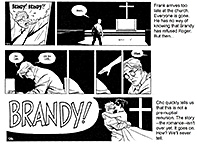

And Cho also displays his complete command of the nuances of storytelling in comic strip form, exploiting the horizontal multi-panel format in ways both imaginative and hilarious. A master of the comic strip idiom, he plumbs the form itself, adroitly deploying its resources for great comedic effects. Not only does he display an exquisite sense of timing in the way he uses the form's inherent capacity for pacing the action, but he exploits the horizontal nature of the medium. In his design, successive panels, while always read in sequence, are sometimes not intended entirely as isolated drawings but as a series of pictures, all existing at the same time to be seen at the same time, spread across the columns of a newspaper page.

|

|

|

|

Laudable as all this achievement is among connoisseurs of the medium, Liberty Meadows is also funny, sometimes outlandishly so. Seldom have the funnies witnessed such a virtuoso performance in so young a cartoonist. And you are about to witness it, too—before you get to the end of this effusion.

AS SOON AS I WITNESSED Brandy trying to get into Frank’s pants, I knew I had to see more of this comic strip, and to that end, I had to meet its creator. How I managed to get in touch with Frank Cho I’ve forgotten. His phone number wasn’t on the strip, but there must’ve been some other clue about where he was because within a few days after the Chicago Con, I was talking with him on the phone.

Cho sent me samples of the strip, and I learned that he was working with Creators Syndicate to get his strip syndicated. I was delighted to hear it, and I then proposed to interview him for Cartoonist PROfiles, the venerable quarterly magazine that Jud Hurd had been publishing since March 1969, and for which I had been producing an article/interview for every issue since ANOTHER DATE. (For more about Hurd and his magazine, see Opus 170.)

Happily, Frank agreed to let me interview him, and then the unexpected happened: Rick Newcombe, president of Creators Syndicate, found out about the impending interview and wanted to contribute to it. He knew that newspaper editors read Hurd’s magazine, and I’m certain that he wanted to make sure my article would present the strip to advantage.

I was a little leery about that: I didn’t want the resulting article to be just a promotion for the strip, which is what I feared it might become if Newcombe were involved in it. But he agreed to let me have the final say: I specified that he could add to the article, but he couldn’t subtract from it.

What follows is essentially the article I wrote for Cartoonist PROfiles. Serendipitously, my article was published in the magazine’s issue for March 1997, the same month that Creators began syndicating Liberty Meadows. Joyous coincidence.

"I WAS BLOWN AWAY BY THE ARTWORK," said Rick Newcombe, president of Creators Syndicate, when I asked him how Frank Cho had secured a contract with his new strip, Liberty Meadows.

"I hadn't seen anything like that cross my desk— in terms of a new submission— in a long time," he continued. "So I walked into Anita Tobias' office— she's our Executive Vice President, one of two--and I said to her, We need to sign this fellow up. And so we did."

That was in the fall of 1995. Liberty Meadows debuted in the spring of 1997. It took that long in development simply because Frank Cho wanted to finish college. He graduated in May 1996 and promptly began working in earnest on the strip.

When I spoke with Newcombe in December 1996, he was, understandably, as enthusiastic about Cho's drawing as ever.

"It's as if Winsor McCay had submitted a comic strip," he said. "I ask you— as a person who's studied the history of comics and written books about it— do you think Frank's drawing is as good as Berke Breathed's and Bill Watterson's?"

I laughed: "Frank Cho can draw circles around Berke Breathed and Bill Watterson," I said.

So much for reportorial objectivity.

I confess: I, too, am blown away by Frank Cho's comic strips. But— as the strips reproduced hereabouts— Cho is more than a superb artist. He is also a master of the comic strip idiom: he plumbs the comic strip form itself, adroitly deploying its resources for great comedic effects.

Not only does he display an exquisite sense of timing in the way he uses the form's inherent capacity for pacing the action, but he often exploits the horizontal nature of the medium as we’ve just seen.

Cho's strips also demonstrate a way to ensure that quality artwork can survive the severe reduction that comic strips must endure these days. Laudable as all this achievement is among connoisseurs of the medium, Liberty Meadows is also funny, sometimes outrageously so.

Cho realized even before submitting strips to syndicates that he would have to abandon the raucous collegiate setting of University2.

"I knew if I got syndicated, I'd be addressing the entire public," he told me when we talked in December 1996, "and the college setting would not reach as wide an audience. So right away before I even sent out my packet, I knew I wanted to do a wildlife preserve and animal shelter and address a lot of the environmental issues."

I asked: "At what point did Frank the duck become Frank the human?"

"That was my invention," Cho said. "Right after I signed a contract, I did some thinking and decided that it would make sense to make Frank a human. And later on, the syndicate agreed that Frank should be a human because they don't think a national audience would buy Brandy dating a duck."

"I don't know why not," I said. "I thought that was just the most natural thing in the world. I never had any trouble with that; not a bit."

Cho laughed: "You're a sick man, Bob."

"I know, I know."

"It kind of made sense to make Frank a human," Cho went on, "and also to make him into a animal doctor and make Brandy the animal psychiatrist. And with those two premises— they're the complete opposite ends of the medical spectrum— you can play a lot of funny ideas off of them, their interaction."

Cho's knowledge of the medical field comes from his college education: he graduated from the University of Maryland with a bachelor's degree in nursing. But he has no special background in animal husbandry or environmental issues.

"Right now I'm doing some research," he said, "but I don't think I'm going to go too deep into environmental issues because I really don't want to have a strong political bent, like Doonesbury. It's going to be a very muted environmental message. I'm not going to delve deep into the politics of it."

I said: "So the strip is really focused on relationships rather than issues. Once you take the duck out of the Brandy-Frank mix, you have a romantic situation in the conventional sense of the phrase, and the dilemmas that men and women have in dealing with each other are going to be more real to readers."

"Fifty percent of the storyline is going to be about the relationship between Frank and Brandy," Cho said. "The other fifty percent will be about the animals around them."

Newcombe agrees with the decision to make Frank a man: "There was a sexual connotation there that was not appropriate," he said.

"Is it any more appropriate if it's between human beings?" I asked.

"Yes," he said, "people date in comic strips all the time. But that's not all. “

He explained that the syndicate sales force believes that this strip appeals to several discrete groups of readers, among them, Generation X and people in their thirties, the group that advertisers are always after in newspaper readership. That’s also the group that the editors are trying to appeal to because the readership is down in this group, and members of this group clearly would be impressed by the dating scenes and by a lot of the sports stuff.

“My seventeen-year-old daughter read the strip,” Newcombe said, “and she just loved it. Then another group is the adults who can appreciate the humor, which is cerebral. It has an intellectual quality to it— just like Johnny Hart or Charles Schulz. So that's good."

By way of proving the strip's appeal to the young adult readers that editors want to reach, Creators is marketing Cho's University2 to college papers. "We showed it to 75 college newspapers," Newcombe told me, "and about 70 of them took it and are running it right now. This is an age group that newspaper editors are working day and night to try to attract."

APART FROM CHANGING Frank from a feathered friend to a fellow homo sapien, Cho made only a few minor adjustments in his supporting cast. Leslie the Laughing Lima Bean became a frog, for instance.

"That was the syndicate's idea," Cho said. "They didn't buy the lima bean thing. In University2, I never explain how Leslie came to be. And the only reason I drew Leslie as a lima bean--a very large lima bean— was that I got lazy drawing characters, so I made one a big Mr. Potatohead-looking thing with a wide open area for facial expression. That's how Leslie came to be."

I laughed: "Seems perfectly sensible to me. Why do all the characters in a comic strip have to be human beings? Why do they all have to be animals? Why can't some of them be vegetables? I don't have any problem with any of that."

"I've actually written up a nice little story about how Leslie came to be in Liberty Meadows as a lima bean," Cho said, "but it wasn't really that important. So I just changed him into a frog. I gave him webbed feet and hands and added some spots."

And there's Dean the chauvinist pig.

"Actually, he's based upon my roommate," Cho said. "And my roommate's name is Dean, too. I didn't even change it. I just talked with Dean every once in awhile, and I'd get a joke out of him."

|

|

|

"And Ralph," I said, "— he was at first a gerbil, wasn't he?"

"I changed him," Cho said. "Ralph is now a former circus bear."

I laughed: "A former circus bear? I see: he was bigger in those days. You shrunk him down."

Cho laughed, too: "A lot of people kept saying, Who's Ralph? Is he a bear or a dog? And I thought bear was funnier."

Julius is a new character.

"He's the director of Liberty Meadows," Cho said. "He will be making very few appearances. He's a sort of bumbling— not really bumbling— but the awkward administrative type. Nice guy but he doesn't have any leadership skills."

At the time we spoke together, Cho was plugging the gaps in his storyline. Although each daily installment of Liberty Meadows carries a punchline, a story emerges over time. He had drawn strips depicting various incidents in a four- or five-week narrative, and he was now going back to connect the pieces.

He works mostly at night. Arising at about noon every day, he watches television for awhile, then, as evening approaches, begins thinking about the day's work. After 11 p.m., he starts working, and he draws and writes until 4 or 5 a.m., then goes to bed.

I asked Cho how difficult it was to adapt his college strip concept to the needs of a family newspaper.

"It's hard in some areas," he said, "but over-all, it went very well. I was surprised at how easy it was. Obviously, there's some stuff that I can't do anymore: I can't draw Brandy quite as voluptuously as I did. And some of the humor has to be toned down. In a college newspaper, I could use certain words. And so to me it was kind of hard at first, but once I got into the grove, I could switch it off and use more decorous stuff. I think I did a pretty good job of maintaining the same type of humor yet not as offensive."

Newcombe agrees.

In the early stages, Newcombe talked to Cho by telephone every couple weeks, passing along to him the criticisms and suggestions made by others in the office. "We channel a lot of feedback to Frank," Newcombe said. "And we hear different things from different people. Some of the women have strong opinions one way, and some of the men have strong opinions the other way. We're trying to balance it.

"We want cutting edge humor," he continued. "But we don't want it to be risque. If we want to sell it in middle America, it's important that it's appropriate for the market. Frank, I think, is hitting his stride now."

I agreed: "I was worried about that— whether you'd be able to retain that edge. And for the most part, I think you have. Obviously, there are no fraternity belching jokes anymore. But there's still an edge in the humor; and it's still unconventional yet understandable."

Newcombe has great confidence in Cho. "It's obvious that Frank loves what he's doing," he said. "That comes through in the drawings and in the writing. I have no doubt that he'll go far. This is the same way I felt about Rick Detorie's One Big Happy, which is now in about 400 newspapers. It's a very successful comic strip. And Rick is a great talent."

FRANK CHO HAS BEEN DRAWING ALL HIS LIFE. "I started drawing as soon as I could grab stuff," he told me with a chuckle. "My mom has pictures of me drawing when I was just a little kid. I guess I always had it in me."

He believes he inherited his artistic ability from his father, who went into accounting instead of pursuing a career in art, and his sense of humor ("the gift of mirth," as he put it) from his mother ("my mother the card"). Born in South Korea, the cartoonist came to this country when his family moved here in 1978, and they settled in Maryland.

"I really got into art around fifth grade [about age ten]," Cho said. "That's when I started collecting comic books like all my friends were. And one comic book that stands out in my memory--it blew my mind away— was Detective Comics, No. 509, drawn by Don Newton. Don Newton I think is the definitive artist in my life. He made everything click. Funny thing— originally, I never intended to become a syndicated cartoonist. I wanted to be a comic book illustrator. And around the same time that I discovered Don Newton, I discovered Frank Frazetta. Those two people really changed my outlook in illustrating."

Cho didn't take art classes in school: "I learned how to draw by mimicking all the comic book artists," he said. "Lucky for me, I tried to imitate Don Newton and John Buscema. Very, very strong roots in classical drawing. So I lucked out that way. I just basically practiced— practiced on my own time, practiced drawing. And I really didn't get into cartoon strips— newspaper cartoon strips— until I was in high school.

"A very good friend of mine was editor-in-chief of the highschool newspaper," Cho continued, "and he invited me to draw a comic strip. And that's pretty much the start on my road to being a syndicated cartoonist."

His highschool strip was a parody. Cho lampooned his teachers and his classmates. And the strip included animal characters, too. Seeing his artwork in print was another learning experience: "I could see all the mistakes that I had made," Cho said.

He did the strip for two years in a monthly newspaper. And after graduation, he entered Prince Georges Community College, where he spent three years— two of them, producing a comic strip for the campus newspaper, The Owl.

"I was a kind of brash young man," Cho said. "And I saw the college newspaper, and the very next day, I walked into the newspaper office, unannounced, and said, I want to be in the newspaper and showed them my strips. And the very next issue, I was in," he chuckled.

That was the starting point of University2. "It was called Everything but the Kitchen Sink," Cho said. "A lot of its characters would make their appearance later in University2. It was like the genesis of University2."

It ran for two-and-a-half years— until Cho entered the Nursing School of the University of Maryland. His family wanted him to pursue a career in the medical field.

"I thought that going to a nursing school would be great," Cho said, "because you'd be surrounded by women. That would double my chances of getting a date. And I look stunning in white."

But after a year, Cho was "going mad." He went into the offices of the student newspaper at College Park, which was located near his home (and he went home every weekend). "I walked in and showed my stuff, and they said, You're in."

It intrigued me that as a fan of Don Newton's superhero work in comic books Cho came up with funny animals for his comic strip. There aren't very many funny animal comic books these days. So I asked him: "How did you get a cast with animals in it?"

"To be honest, I don't know," Cho said. "Don't get me wrong: I didn't focus only on comic books. I read a lot of comic strip books, reprints. I guess Bloom County had influenced me greatly without me really knowing it. I didn't really try to mimic Bloom County style, but a lot of people who read my stuff said, You're very influenced heavily by Bloom County."

I said: "There are animals in that strip. The penguin. A couple of others."

"The kind of look that I wanted to get with my comic strip was Li'l Abner," Cho said, "--as you may have noticed with Brandy and some of the other women. Funny thing, I found out that those women in Li'l Abner were drawn by Frazetta for nine years. I had reprints of old Li'l Abner stuff. And it was from the fifties, and I found out that was when Frazetta was ghosting for Al Capp."

Cho wasn't influenced by Walt Kelly's Pogo at all. "It was before my time, and I couldn't find reprints. The strips I was reading— and I really didn't start reading newspaper strips until I was in high school, doing my highschool strips— the strips I read were the top three, I guess: Calvin and Hobbes, Bloom County, and The Far Side. My taste in comic strip material is kind of mainstream."

By this time, Cho had stopped collecting comic books. "It just got too expensive," he said. "And puberty pretty much got a hold of me, and I was lusting after women."

While he was reading comic books, he read Marvel titles and Batman from DC. "I remember buying Miller's Dark Knight Returns [which was published in 1986]."

Although he no longer bought comic books regularly, Cho still visited comic book stores and looked at the books on the stands, occasionally buying one that caught his eye. "I kept in touch with what was happening in the comic book industry. But I just basically got tired of the same old superhero stuff."

He started paying attention to alternative press material— Evan Dorkin's Milk and Cheese and Peter Bagge with Hate. And he discovered European cartoonists through Heavy Metal magazine. "I really enjoyed stuff where people could really draw!"

University2 debuted in the Diamondback in the fall of 1994. In the winter of that year, Cho heard about the Scripps Howard Foundation National Journalism Awards, which, in cartooning, is offered only to college cartoonists. He submitted twenty of his strips ("from the first semester— which I thought was the weakest semester") to the competition. And he won (in a field of 157 submissions) and was awarded the Charles Schulz Plaque for Excellence in Cartooning at a black-tie affair in April 1995 in Memphis.

"Those Scripps Howard people really know how to throw an awards ceremony," Cho said. "It was pretty wild. Al Gore was the guest speaker— via television; he didn't appear live. But it was very nice. The governor of Tennessee and the mayor of Memphis showed up. And they were giving out awards to the best news reporter, the best editor, and they came to me, the best college cartoonist. That was kind of awkward. I'm surrounded by the cream of the crop in the journalist field, and here I am, a little nobody, a college boy."

The experience prompted him to actively pursue syndication.

"I

made up a sample packet entitled Liberty Meadows," Cho said.

"I didn't re-write anything— just slapped together thirty daily strips

from my University2 and quickly made it as ambiguous as

possible. I just said, Liberty Meadows is a wildlife preserve and animal

shelter, and pretty much ran with that. I picked strips that didn't

address any college issues and sent the packet out to all the major

syndicates."

Most syndicates rejected Cho's strip because it was too off-beat, too novel. Creators Syndicate liked it for reasons that were, so to speak, the positive side of the same coin: it was fresh and hip.

As Newcombe put it, "It didn't take great imagination to see how you could convert this strip to a strip that would be popular in a family newspaper and still preserve the essential character of Frank's work."

Judging from the quality of Cho's work, the risk is not as great as it might seem. Cho had established himself as a college newspaper strip cartoonist: like Garry Trudeau and Berke Breathed, he had a body of work to show when he set out to become syndicated, and he had a track record, producing steadily for regular publication over a period of several years.

Nonetheless, for Creators' willingness to take him on, Cho was thankful: "I'm very, very grateful to them for taking a chance on me like this," he said.

The chance Creators took lasted only five years: Liberty Meadows ceased on December 30, 2001.

Cho’s primary attachment to cartooning was through comicbooks, not comic strips. Most cartoonists who get their comic creation syndicated are delighted at the prospect of life-long employment. But not Cho.

“I dreaded the thought that Liberty Meadows would continue indefinitely,” he said. “I consider myself a storyteller, and I had many other stories I wanted to tell.”

Cho was beginning to feel the urge to paint—and to sculpt! And, as St. Wikipedia put it, he was “weary of the arguments with his editor over the censorship of the strip as well as the pressure of the daily deadlines.”

His talent and his achievement with Liberty Meadows opened the door with comicbook publishers, and he began drawing covers and stories for Marvel and stories for Dynamite Entertainment and other publishers. At first, he specialized in jungle girl stories, drawing shapely heroines in scanty attire. Eventually, he was contracted by DC Comics to draw covers for Wonder Woman and Harley Quinn comicbooks.

His comicbook covers are not just pretty pictures of well endowed women (although they are that). As a comic strip storyteller, Cho had developed an already keen sense of humor, and many of his comicbook covers are stand-alone sight gags.

He also made a deal with Insight Studios to reprint Liberty Meadows in comicbook form, and he produced a special cover in color for each issue. With No.27, Image Comics took over the publication of the comicbook, which ceased with No.37, the only issue that contained new material not reprinted comic strips. Image has also collected issues of the comicbook between hardcovers, selling Liberty Meadows in book form. Cho wanted to continue comicbook publication of Liberty Meadows but was unable to find the time while engaged in many other projects.

In an interview included in a recent collection of his work, The Art of Frank Cho (reviewed in Opus 408), we learn that he has taken up painting—he loves painting on a giant scale, canvasses eight or ten feet tall. And he’s dabbling in sculpture. But that’s another story for another day.

He continues to do comicbook covers, but I suppose it won’t be long before a book of his paintings arrives.

Meanwhile, for the present nonce, we have a long gallery of his comic strip and related work to contemplate nearby.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|