FAY KING, PRIZE-FIGHTING CARTOONIST

The Greatest Woman Cartoonist, Caricaturist and ‘Kidder’ in the World

— And Where Did She Disappear To?

IF FAY KING HADN’T MARRIED A PRIZE FIGHTER named “Battling” Nelson, we’d

know almost nothing about her life. We know her opinions about the manners and

mores of the twenties and thirties from her comic strips, cartoons and columns.

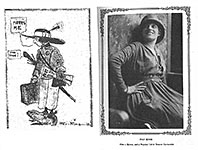

And we have an inkling of what she looked like because she often included

self-deprecating caricatures of herself in her cartoons or to accompany her

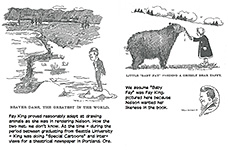

columns. But just an inkling. Her picture of herself as a skinny Olive Oyl

personage with a large pointy nose and gigantic feet was a cartoonist’s satire

of herself and is not to be taken literally. (Besides, Olive Oyl hadn’t

been invented when King started using her self-portrait.)  Fay King was actually a quite

attractive albeit diminutive woman, barely five feet tall.

Fay King was actually a quite

attractive albeit diminutive woman, barely five feet tall.

Gene Fowler, a fellow journalist and co-conspiring staffer at the Denver Post, recorded his reaction to King upon first meeting her in her hotel room. “She was a petite, lively girl. ... I was unprepared to come upon so much vitality in such a small package. She was dark-complexioned with very large dark eyes, and she wore numerous pieces of jewelry which chimed like bells as she played with nine canary birds who shared her room in the hotel. There were gold hoops in her ears, and on one forefinger she wore a heavy gold band to which was affixed a cartoon effigy of herself. She was part gypsy.

“The canary birds were fluttering about the room,” Fowler continued, “— sometimes alighting upon her head and shoulders. They seemed charmed by her cries and her laughter.”

In Timberline, his history of the Denver Post, Fowler described King as “temperamental, capable of fainting when one of her numerous canary birds met with an accident, or of fighting a bobcat if necessary.”

Not all of this description could Fowler have conjured from his first encounter with King. So we may as well admit that after meeting this spritely canary fancier, Fowler dated her for quite some time—long enough that people began to assume that they would get married. They both denied any such inclination; but that story comes later in this disquisition in its appropriate chronological niche.

Fay King arrived at the Denver Post, her first professional gig, April 20, 1912 when she was 23 years old. At the end of July that year—three months later—she was interviewing Nelson.

Oscar Matthew Nelson was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, on June 5, 1882, and he accompanied his family when they emigrated to the United States the following year. He grew up in Hegewisch, a neighborhood on the southeast edge of Chicago near Burnham. By the time Fay King met him, he had been mayor of Hegewisch and owned a lot of land there, all of which he may have acquired with the earnings of his prize-fighting career.

According to St. Wikipedia, Nelson (sometimes called “the Durable Dane”) began boxing professionally when he was 14 in 1896. On December 20, 1904, he fought Jimmy Britt for the vacant lightweight title but lost in a twenty-round decision. Nine months later, he had a return match with Britt, and this time he won with an 18-round knockout.

Nelson lost the title the next year to Joe Gans in a 42-round decision. He regained the title from Gans in 1908 and successfully defended his title several times thereafter, but he lost it again in 1910 to Ad Wolgast in a fight so fierce it inspired a book about it. Nelson lost because his face was so battered and bleeding that he couldn’t see, and the referee stopped the fight in either the fortieth or forty-second round.

Nelson continued to fight for a few more years, retiring from the ring in 1920 (or a little earlier, depending upon whether we believe the vow he took with Fay King to give it all up in 1913; nope, we don’t believe it). But he was still active as a professional prize fighter when he met King for an interview at the end of July 1912.

The result of the interview was published in the Post on July 29 under the headline: “Battling Nelson, Capitalist, Author, Mayor of Hegewisch and Greatest of Ring Champions, Is Visiting in Denver.”

Excerpts from the article follow—:

Said King: “How about this latest rumor about your marriage to Miss Irma Kilgallen, the beautiful Chicago heiress? You admit you were sweet on her—won’t you tell me all about it?”

“Well,”

responded Nelson, “I think it was a case of love at first sight when Irma and I

first met, seven years ago in Chicago, and it was mutual. Somehow we both

looked forward to love in a cottage, but then came her fateful trip to Europe,

when she married that bum, Count No Account, to please her mother.”

In those distant days, some few American women of marriage age went to Europe to marry European nobles, who were paupers looking for an income with a wealthy woman. And the women were looking for a title.

“Do you think you’ll ever marry, Bat,” King persisted (“remembering it was leap year”).

“If I believed in dreams,” said Nelson, “I should say NOT because the other night I dreamed I was married and presented my country with five young lightweights all at one time! [Quintuplets, one of whom Nelson named William Jennings Bryan.] ... I was just opening congratulatory telegrams from all the dignitaries of the U.S.A. when I awoke. Do you wonder I hesitate to enter a (wedding) ring career after a jolt like that.”

Neither of them knew it at the time, but more jolts were forthcoming.

Shortly after the interview, the two of them went off together to see a baseball game, and King regaled her readers with their adventures in her cartoon published on July 30. A few days later, they went to a circus that was in town, as King reported in her cartoon published on August 3. King had previously made Nelson the subject of her cartoon that was published next to the interview on July 29.

|

|

|

We may ponder in this sequence of events the lightning spark of a budding romance. But maybe the sparks had been kindled earlier: the two had known each other since 1911, when King drew a picture of Nelson for his book, The Wonders of Yellowstone Park.

Still, it looked like events were spiraling into consequence.

Not quite a week after the interview was published, they were apparently a couple, and they went up to the summit of Pike’s Peak. According to report, they’d arranged to be married there. But the preacher got tired of waiting and left them stranded 14,115 feet above sea level.

One of the people at the summit was an undertaker who offered to perform the ceremony, but Nelson was not persuaded. The San Francisco Call’s report of the Pike’s Peak fiasco declared that Nelson decided to make other arrangements for a wedding, which, he said, would conclude with a honeymoon in Australia.

The Pike’s Peak episode sounds very much like some sort of publicity stunt rather than a serious attempt at marriage. But if it were a stunt, it didn’t end properly—with a joke. Except maybe the undertaker. If he were the punchline, however, it was grave rather than jolly.

Nelson was interviewed about the near miss at nuptials on September 29, but he dodged most of the questions, which began with: “Is it true that your rumored engagement with Miss Fay King of Denver is all off?”

Miss King, said the interviewer, says she loves you like a brother but she has not considered you for a husband.

Nelson said the only match he knew about was the one that his Chicago representative was trying to set up with another boxer, Packey McFarland.

But the reporter was persistent, and Nelson finally surrendered (after a fashion):

“I’m not going to talk about marriage,” said Bat, and then went on to talk about it. “I am leaving the matter up to her. What she says is right, no matter if she’s wrong.”

He continued at greater (more exasperated) length: “There’s no use in my talking marriage. Any man who says he’s going to marry a woman is crazy unless he has her right at the altar—and even then he’s liable to be fooled. She may not like the color of his necktie and call off the match.

“Miss King,” he went on, “is a fine cartoonist, and she’d make a fine wife for anybody. If I’m the lucky fellow at the finish, I’ll be tickled to death, that’s all. But I’m not saying a word one way or the other on the time, the place or the girl.”

Without further ado, they were wed four months later.

KING FINALLY MARRIED her prize fighter on Thursday, January 23, 1913. The Denver Post reported the progression of events that led to the altar.

Nelson arrived in Denver on Monday, January 20, with the intention of conducting a 4-day whirlwind campaign. “When the former champion arrived in the city, he was determined that when he left he would take Miss King along with him. He was not prepared for any long stay, and he wasted no time in completing his conquest: on Tuesday evening, the young artist had yielded to his forceful wooing and agreed to accompany him back to Illinois. They are on their way now, and by Thursday night will have been married and have held their wedding reception in Hegewisch.

“Personal friends of the couple have known for some time that Fay King and Battling Nelson were in love with each other. But there was no intimation on the part of either that an early marriage was contemplated.

“Miss King had not anticipated any such quick move on the part of her fiancé, but after his arrival, she decided with him that there wasn’t any use in delaying the marriage, so she obtained a leave of absence [from the Post] and joined in with his plans.”

Another newspaper, The Call, recorded the event on January 23—:

“Oscar Matthew Nelson, once famed as the lightweight champion pugilist, and Miss Fay Barbara King, a Denver cartoonist, were married today at the fighter’s home in Hegewisch. The ceremony was brief, but as the final words fell from the minister’s lips, the bride, overcome by the nervous strain, swayed and toppled over into her husband’s arms, sobbing violently. ‘Bat’ soothed his bride, and pretty soon she smiled and said, ‘I feel much better after my cry.’

“Outside, a brass band burst forth into ‘Moonlight Bay.’

“‘I’m the happiest guy in the world,’ said Bat.

“Asked about his wife’s future, the groom said, ‘She’ll probably devote her time to illustrating my map [i.e., face]. But I’ll stay in the ring. I’ve got to as that’s the only way I have of making a living.’

“The trip downtown to Bat’s home was a gala affair. A special car on the Illinois Central was chartered [for the journey from central Chicago to Hegewisch] and a band hired. On the train, Miss King drew a cartoon of the pugilist.

“The moving picture men were clamoring for some pictures and set up their machines before the happy pair. The band played and ‘Bat’ leaned over and kissed his bride-to-be twice, and the picture machines got it all.

“A big crowd turned out at Hegewisch to greet ‘Bat’ and his fiancee. There were vigorous cheers as the party stepped from the train. The band played as the long line of friends, townsmen, newspaper men, moving picture operators and photographers started for the Nelson home behind the bridal party in a big automobile.

“The couple came to Chicago after the ceremony, and a wedding breakfast was served at the Wellington hotel. Tonight, the couple entertained friends at a theater.”

Alas, the marriage was short. And perhaps turbulent. Three days after the wedding, King left her husband, returned to Denver, and filed for divorce. She went on to Portland, Oregon, to visit her parents before resuming her work at the Post.

One newspaper account said: “Bat couldn’t stop the battling, even at home, throwing the piano at her or whatever it was. Fay was suing for divorce after only six weeks though both parties said the marriage lasted only three days.”

Nelson’s father saw his son as a bit of an odd duck. “Bat is crazy as a bat,” he once said.

“Every

detail was printed across the nation. A syndicated article told the story in

terms of a five-round bout with illustrations by King, one of which has Bat on

his back, out for the count. Another picture has Cupid with a black eye.”

In her suit, King maintained that she had been kidnaped by Nelson on the night of January 20 for her marriage three days later at the fighter’s home in Illinois.

Remembering the events of the last week in January, King said: “Nelson heard of my reported engagement to a Denver man and he stopped his fighting engagements to come here for me. He took me by storm after I was weak and a nervous wreck from resisting him and his proposals. He forced me into a taxicab and rushed me off to the station.

“I realized that I had made a mistake the day of the wedding, and the first opportunity I got, I hurried back to Denver. I will go right on working at the Post as though the affair had never happened. The marriage must not and will not stand.”

Right about this time, Fay King met Gene Fowler.

GENE FOWLER came right out of Ben Hecht and Charlie MacArthur’s “The Front Page.” Fowler, like other newspaper legends of his day, was “hard-drinking, irreverent, girl-goosing, and iconoclastic.” They were all “young men wearing snap-brim hats with cigarettes dangling from their whiskey-wet lips and bent on insulting any and all individuals who stood in their paths, no matter how celebrated or sacrosanct.”

“There are some who complain about this popular depiction, insisting that it is not a true portrait” said H. Allen Smith in his biography of Fowler (The Life and Legend of....), “—that the gin-soaked reprobates were few in number.

“They lie in their teeth,” Smith finished, emphatically.

“It is probable,” he continued, “that a majority of newspapermen and freelance writers are heathens, freethinkers, or outright atheists. It is likely that most people in the theatrical professions are nonbelievers if not scoffers. Gene Fowler worked and frolicked with such people all his adult life, enjoying their company as they enjoyed his.”

At the time Fowler met Fay King, he was still working at the Rocky Mountain News, one of the other Denver newspapers (he would join the Post staff a few weeks later), and he had been assigned to interview the cartoonist, who was staying at a hotel in downtown Denver. She was of news interest at the moment because she was reported to be divorcing her husband, Battling Nelson.

Fowler had just concluded—or, rather, been excluded from—two romances, one with the bugler in a Salvation Army band; the other—on the rebound—with the daughter of a wealthy Denver resident far above Fowler’s station in life as a newspaper reporter. So Fowler was vulnerable to Fay King’s charms.

Writes Smith: “Handsome Mr. Fowler called on Miss King in her hotel suite and found her with nine pet canaries fluttering around her pretty head. Nine hundred canaries began fluttering inside Mr. Fowler, and he hurried to the main point: was it true that she was divorcing Bat Nelson? She said it was.

‘Have the papers been filed?’ he asked her.

She replied: ‘Do you like corn on the cob?’

“Within ten minutes, they were downstairs in the hotel, looking for corn on the cob.”

Before too many more afternoons had passed, Fowler was regularly squiring Fay King around town. Within a short time, it was being noised about in the Press Club that Fowler and King were planning on marriage. They both denied it.

But, Smith reported, Battling Nelson heard the rumor. “He was carrying a torch for Miss King and came to town packing a gun and saying he was gonna take dead aim and shoot Fowler’s groin to tatters.

“Our young Lochinvar [Fowler] skulked through alleys for a while and left restaurants by their kitchen doors. He was not a coward, but he had lately been fired upon for the first time in his life, and he had grown gun-shy.”

He had been assaulted by a stout middle-aged woman with a dangerous glint in her eye. She fired at Fowler four times, missing every time and claiming throughout that she intended to “kill the polecat who had betrayed her daughter.” That polecat, it turned out, was not Fowler; he had merely written and bylined a story about the polecat in question. The stout lady assumed from the byline that Fowler was the culprit she sought. The episode made Fowler leery of strangers with glints in their eyes who might be armed.

Asked point-blank if he and Fay King were going to get married, Fowler (Smith says) responded:

“Jesus, no. Neither one of us believes in it. Marriage is for dumb and stuffy people who can’t think of any place to go.”

Regardless, Fowler’s romancing of Fay King went on apace. And he wrote about their relationship in his autobiography, A Solo in Tom-Toms.

“Fay King was one of the few women cartoonists in the newspaper world. She wrote articles to accompany her drawings, and both her art and her articles had a freshness and a simple originality which revealed their creator as an extraordinary person.

“She was the daughter of an old-time trainer of athletes in Seattle. Many champions had seen her grow from childhood to young womanhood, and regarded her as their mascot.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recalling his first encounter with the tiny woman with canaries in her hair, Fowler wrote:

“‘Shut the door!’ Miss King called out. If one of my little birds got away, I’d be sure to die. What’s your name? I didn’t catch it over the telephone. I hope it’s not Schultz.’

“I told her my name, and when she asked what it was I kept staring at, I replied, ‘Those earrings.’

‘Don’t you admire them?’ she asked.

‘I’d like to chin myself on them,’ I said. Then I became businesslike. ‘Is it true you left Battling Nelson the first week of your honeymoon? Is there to be a divorce?’

‘Yes,’ she said frankly. ‘But I wish you wouldn’t print it.’

‘And why not?’

‘I don’t like to make him feel sad,’ she said. ‘Whenever anybody feels sad, I want to cry too. I don’t like to cry: it makes my mascara run.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘You’d better outfit yourself with a big supply of handkerchiefs.’

‘You mean you’ll print it?’

‘What else? You’re both public figures. Have you filed papers?’

“She amazed me by asking, ‘Do you like corn on the cob? I mean, after it’s cut off and piled high on the plate?’

‘I like it that way best of all,’ I replied. ‘Is that what caused your divorce? Whether corn should be cut off the cob?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘But let’s go down to the cafeteria.’

‘Fresh corn is not in season,’ I reminded her.

‘I know,’ she replied. ‘But we can have some canned corn. When I crave something, I must have it right away.’

“As if she did not have on enough jewelry already, she found some more bracelets. And by the time she was ready to start out, she was more ornate than an admiral’s arm. She liked gay colors also, and when she had assembled her various scarves and sashes, she reminded me of the mountain of flowers of August.

‘I am simply mad about cafeterias,’ she said, then announced matter-of-factly, ‘I think I’m going to like you. Do you mind?’

‘Not at all,’ I said. ‘I’m one of those fellows who likes to be liked.’

“She looked at me and said, ‘Oh.’

“We had canned corn that night at the cafeteria. And when summer came, we had corn cut from the cob. And we also shared laughter and great affection. In this completely honest and honorable person I found one of those friends who never die. Fay had an unreasonably high estimation of me, and I tried—at times—to live up to it.

“Our principal bond was laughter, and our attraction, one for the other, arose from the circumstance that two wild-natured creatures found companionship, honesty of expression, and instant understanding. Loneliness went away.

“We differed in several respects, of course. Beneath the carefree, gypsy personality of this girl lay the inflexible soul of a moralist. One could not justifiably call her a prude; still she had a puritanical code which she revealed only to those who knew her in private life. She herself was abstemious, yet uncritical of the indulgences of others.

“She did not endeavor to reform me in the usual ineffectual manner of well-meaning persons who think that bridles, saddles, spurs and quirts can tame desire. Rather, she undertook an educational campaign to make me believe what she sincerely thought herself, that I had within me the materials of manhood and achievement. So earnest was she belief in my potentialities that I began to believe in them myself.

“It was difficult for me, however, to wear blinders when exposed to romantic issues. In respect to my extreme fondness for the ladies, Fay remarked: ‘When men like you and Columbus discover something, you go overboard with delight.’

“This girl and I, both lately wounded by a careless Cupid, together laughed our way through spring and summer. ...

“I worked nights and Fay King worked days. The young cartoonist’s editors objected to her late hours in my company, but she had a way of charming them. ... Fay and I together attended the baseball games and prizefights, for now I was writing of sports [for the Denver Post] as well as other events. Because of her girlhood among the champions, as well as her analytical mind, she was an excellent appraiser of athletes and their games.

“She was the only woman I ever knew who fully understood the fine points, such as the fact that a short punch actually originates in a boxer’s legs and is much more effective than a showy, swinging blow that has little behind it but the torso and shoulder. When I began to referee the professional fights, she would view my mistakes with the stern eye of a critic, and I was happy indeed that she didn’t publish these opinions in her cartoons or columns.”

BEFORE FOWLER STARTED LAUGHING his way through summer 1913 with the lady cartoonist, his friendship with her suffered a wedge. Battling Nelson was back with Fay by that spring. It’s not entirely likely that they were living together as a married couple in Denver, where King continued to work. But the divorce had never gone through, and Nelson had taken an unusual step to please his wife.

The Call on May 6, 1913 reported that Nelson intended to retire from his bruising profession that fall. “There’s no idle boast connected with the announcement. It may not be the wish of the once durable Dane to put the gloves on the shelf, but it is the request of Mrs. Battling Nelson, Fay King, and Fay has the say.

“Labor Day will be the Dane’s last fight—this because it will be the eighteenth anniversary of his fighting career. He would quit now but for that. There will be no fights between now and September, however.”

But he likely did not quit boxing forever that fall. Wikipedia claims he didn’t retire from the ring until 1920. By then, he’d fought in 135 prize fights and won 73 of them, 40 by knock-outs.

The Call continues: “Nelson and his wife are now in Bedford, Virginia, resting up. Bat plans on settling in the far West.”

If he’s going to settle in the far West, where will Fay be? Still in Denver? No indication is supplied by The Call.

But the couple was back in the news in March 1916, and the report published on March 3 cleared up, a little, the status of the couple after the summer of 1913.

The headlines for the article tell the story:

“Bat Nelson to Secure Divorce”

“Judge Indicates He Will Grant Separation from Fay King”

The article elaborates:

“Oscar Battling Nelson, former lightweight champion, testifying before Judge George Kersten in the Circuit court, in his suit for divorce against Fay King Nelson, asserted that their marriage had never been consummated. He alleged that they had never lived together as husband and wife.

“The hearing was by default. ‘Bat’ charged desertion in his bill. Upon examination by his attorney, the ex-pugilist said he married Mrs. Nelson in January 1913.

‘How long did you live together?’

‘She left me three days after our marriage,’ he replied.

‘Did she return?’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but she went away again.’

‘How long have you been separated?’ the Judge interposed.

‘Since November 1913.’

Nelson said King never loved him but regarded him as a “li’l pal.” He introduced some letters from her in which she referred to him as a “dear little woolly lamb.”

After hearing the evidence, the Judge indicated that he would grant a divorce.

So, they were together in Bedford, Virginia for a period in the spring of 1913. And they were together again, apparently, later that year. Maybe for all of the summer and fall. But Nelson hadn’t seen his ostensible wife since that November, so the summer and fall is the extent of their cohabitation—which Nelson, in effect, denies.

The two didn’t appear together in print again until the winter of 1954. On February 7, Nelson, at the age of 71, died in the Chicago State Hospital, a mental institution, where he had been committed, “a man out of contact with the world.” He had lost everything in the financial crash of 1929 and faded from public view.

Nelson’s death was attributed to senility by one source, lung cancer by another.

When Fay King was told of his death, her response was: “He was such a noble, honest man, he did not deserve such a tragic end.”

She said she hadn’t seen him since 1919. But she took the unusual step of defraying the expenses of the funeral so Nelson could be buried in Chicago next to his second wife, “whom he loved so much,” who had died just two months before, December 26, 1953.

FAY BARBARA KING was born in Seattle, Washington, sometime in March 1889. Her family, father John and mother Ella, was reported twice in the U.S. census of 1990, and in both reports, the Kings then lived in Portland, Oregon—albeit at different addresses (323 Alder Street and 590 Front Street). John King was employed at a Turkish bath and was a trainer of athletes, from which his daughter acquired a knowledge of and affection for sports. “She grew up surrounded by sportsmen and pugilists,” Trina Robbins says in her Women and the Comics.

Fay grew up in Portland and attracted the attention of the city’s Oregonian newspaper at least four times, saith Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, the most complete compilation of information about her. (And about almost any other cartoonist you’d care to name; try it, you’ll like it. We’ve relied upon it for most of this essay.)

The first time Fay made it into print was on August 7, 1901, when, at the age of 12, she won second prize in the 50-yard dash on Woodmen’s Day.

And then on December 4, 1904 (when the Kings had moved to 830 Raleigh Street) the Oregonian reported on Fay’s “marked” artistic ability. She had drawn pictures in color of various local dignitaries who participated in a benefit at the Columbia Theater—“all splendid likenesses,” the paper opined.

Fay said the first drawings she’d ever made were of paper dolls that she did when “I was just a bit of a girl.” Her ambition, she said, was to be a cartoonist.

Attending Seattle University, Fay cartooned and wrote for the campus newspaper, The Spectator.

The next that the Oregonian noticed her was on July 2, 1911 with an article and a photograph of her in a new car, a gift from her father (perhaps on the occasion of her graduating from SU). Fay was, it is asserted in various places, “one of the first women in the Portland area to own an automobile.”

Another sign of her adventurous spirit was her plan to make an ascension in a hot air balloon in August with noted early parachutist Tiny Broadwick. But that plan was frustrated by the advance notice of her intention, which alerted her parents, who, the Oregonian said, “emphatically set their parental feet down and announced that no such action would be permitted. Miss King is an only daughter.”

What Fay King did for the next eight months we don’t know. But she must’ve done some drawing for publication—perhaps in the Oregonian. She did enough of it to assemble a portfolio of samples that she presumably sent to various other newspapers, advertising her services. One of those papers, the Denver Post, took her up on the offer and hired her.

HER IMPENDING ARRIVAL at the Post was announced on Thursday, April 18, 1912, under the headline: Fay King’s Coming; Sends a Picture So Denver’ll Know Her —followed by an introductory article, which we post next (in italics)—:

Fay King is coming to Denver.

Know her? Well, if you do not, you will mighty soon, for she is to join the Post staff on Saturday this week.

Fay King is the greatest woman cartoonist, caricaturist and “kidder” in the world today, and she’s just bubbling over with fun of most contagious, infectious kind.

You’ll laugh with her, for you just can’t help yourself.

Fay King is young—very young, in fact—but the hats of veterans in the comic art world are off to her. She comes to Denver from the Pacific northwest, where she had made a tremendous hit. [No indication about how she managed this feat.]

She not only makes pictures but she writes and writes well.

She’s a writer, a critic and a cartoonist in one, and good in each and every line.

Here’s the letter she sent to F.G. Bonfils [editor/publisher of the Post] in response to his telegram inviting her to join the Post family:

Mr. F.G. Bonfils

The Post

Denver, Colorado

Dear Mr. Bonfils—

Your telegram received. I bought my ticket today and will leave here Thursday (April 18) at l0 a.m., and will arrive in Denver Saturday (April 20) at 10 a.m.

You

are very kind to come to the depot and meet me. You don’t know how much I will

appreciate it. That you may know me, I will be dressed like the enclosed sketch

and will carry a Denver

Post.

You

are very kind to come to the depot and meet me. You don’t know how much I will

appreciate it. That you may know me, I will be dressed like the enclosed sketch

and will carry a Denver

Post.

Sincerely,

Fay King

And the sketch (the article resumes) that she enclosed—well, just look at it and see if you can keep from laughing.

TWO YEARS LATER, in January 1918, Fay King left Denver and the Denver Post for the San Francisco where she joined the Hearst syndicate for national distribution. By the end of the year, she was in New York and her work was appearing in Hearst’s tabloid, the New York Mirror. The 1920 census reports that King was living at the Pennsylvania Hotel (the one whose telephone number has been immortalized by Glenn Miller in a song title, “Pennsylvania Six Five Thousand”) at 425 Seventh Avenue, just across from Penn Station.

King’s cartoons and comic strips commented on the ephemera of popular culture and were usually accompanied beneath by text, written by King. Wikipedia observes that King’s cartooning efforts were among the early examples of autobiographical comics, but I can’t recall any other comics in the “autobiographical” category; besides, just inserting into your comic strip a self-caricature does not make the strip autobiographical.

|

|

|

|

But that is a quibble. The Fay King self-caricature was comical and personable and was undoubtedly the aspect of her work that was most popular, assuring her a place in the affections of her readers for years.

Although King’s strips included her opinions and referred to events in her life, as Marilyn Slater observed at freewebs.com, “her work in many ways also tells a history of the new and emerging women of her era.”

St. Wikipedia credits King with the creation of two short-lived comic strips: Mazie (in 1924, briefly) and Girls Will Be Girls (1924-25). About the latter, King wrote a lengthy article for the February 1925 issue of Circulation, a syndicate promotional publication. Herewith, we quote all of her treatise in italics:

Fay King’s Recipe for Success—Pretty Girls and Eating Onions

By

Fay King

No doubt all of us have secret ambitions though we may never voice them or

reach them.

I had a secret ambition, but I voiced it and have reached it!

I am doing a comic strip!

Many is the time I sat at my desk turning out my regular daily story and little cartoon, looking with longing and envy at the favored folks who do “the funnies.” What must be their joy working each day in those little squares, following the career of the creatures they have created—imaginary folks that have become very real to everyone!

Surely work like that must be fun!

Well, since starting my own strip, which I call “Girls Will Be Girls,” I have found the fun is work all right— but I do enjoy doing it!

Being a girl, I decided that girl topics would be more in my line, and that my strip should have lots of girls, and all kinds of girls, and deal with the ambitions, loves, hopes, disappointments, harmless deceits, and daily changing fashions so dear to the heart of every girl, no matter how young or old she may be!

Working girls, society girls, lazy girls, busy girls, and girls of every variety and walk of life I hope to introduce along with their problems, and I think it is going to be great fun! Blondes, brunettes, bobbed hair and long, tall girls and short girls, fat girls and lean girls—but all PRETTY girls!

My girls are all pretty, because I have not the heart to make them otherwise when a turn of my

|

|

pen can make their destiny!

They are good dressers and popular!

Their beaux are all nice looking, too; because even if a man is short, or fat, or bald he can be attractive!

This

is truly a day in which “girls will be girls” much as we once said “boys will

be boys.”

I have long harbored the thought that a strip about Girls done by a Girl might

be made quite interesting, and that’s why I am so interested in doing Girls Will Be Girls.

Alan Holtz, from whose Strippers Guide I poached this article, says Girls Will Be Girls ran in Hearst’s New York Mirror. “If there was a syndication attempt it was a failure. According to Jeffrey Lindenblatt [a comic strip historian] the strip ran there from June 24, 1924 to March 19, 1925. In other words it was canceled only a month after this breathlessly positive article ran in Circulation.”

The short lives of King’s comic strips may not indicate any dwindling status for King. In fact, we have evidence of her continued popularity through the decade and into the next.

Trina Robbins, herstorian, in two of her books (A Century of Women Cartoonists, 1993, and Women and the Comics with Catherine Yronwode, 1995) cites cartoonist/historian Chuck Thorndike, who, she says, in his 1939 book, The Business of Cartooning, “refers to Fay King as one of the five top women cartoonists in America.” Thorndike’s book offers short biographies of 70-plus cartoonists, arranged alphabetically, and I don’t see Fay King in the list. But there is other evidence of King’s popularity—scant, but telling.

In

the 1924 MGM movie “The Great White Way,” King appeared as herself with other

popular jazz age cartoonists—George McManus, Bill DeBeck, Nell Brinkley, Winsor

McCay. And in 1928, she covered the sensational trial of Ruth Snyder, who was

convicted of murdering her husband Albert and was sentenced to die at New

York’s Sing Sing Prison. The photograph of her in the electric chair was widely

circulated. King alternated with Nell Brinkley in recording the daily

events of the trial.

We almost lose track of Fay King at this point in the narrative of her life. Very little evidence in print is available about what she did next.

In his column “New York Day by Day” on October 25, 1934, O.O. McIntyre calls“Fay King, so far as I know, America’s only lady newspaper cartoonist.” Which only shows his ignorance: among the female newspaper cartoonists at the time were Ethel Hays (Ethel), Virginia Huget, Gladys Parker (Mopsy), Edwina Dumm (Cap Stubbs and Tippie), Martha Orr and Dale Conner (both on Mary Worth) not to mention Nell Brinkley

But McIntyre goes on, supplying a little more detail about the cartoonist’s life. He says King is “the most pronounced recluse among the limners. Vivacious and sparkling, she is sought wherever crowds gather but rarely responds [to those invitations]. I have yet to see her at any of the whirligigs of literary folk. She resides at a sedate midtown hotel [probably, according to the 1930 census, the Commodore next to Grand Central Station], is an indefatigable walker, devoted to a canary and a frequent loiterer in the galleries. But she is—and that’s unusual for a Manhattan celebrity—a strictly no-party girl.”

Nonetheless, Fay King was popular enough with the public for MGM to include her in that 1924 movie, and C.J. Coffman mentions King in his column Analyzing You in 1930: “How perennially the effervescence bursts forth in the work of Fay King, philosopher-cartoonist, beloved of the millions.” And later, in 1936, she is listed in a Joe Palooka comic strip among other celebrities ring-side at a Palooka prize fight. But after that, she sinks from view until the report of her funding Nelson’s funeral in 1954.

Th 1954 article is “the last record of King’s existence” according to reddit.com’s author.

Wikipedia says she’s “presumed dead” after the 1954 notice.

Reddit again: “The only potential later reference [to King] was in 1967, when the New York Times produced an article on a dog salon operated by a ‘freelance writer’ named Fay King. This may not be the same person: the article made no mention of her cartooning career.” If it is Fay King the former cartoonist, she’d be 78 at the time, “making it unlikely (but not impossible) that she would be running a business.”

Still, King was fond of canaries— and dogs. She once (at the time of her arrival in New York) owned a wire-haired fox terrier named Tippy, who became lost, prompting King to place an ad in the Evening Telegram’s “Lost and Found” section. That, admittedly, was over 50 years before the dog salon, but affection for pets does not diminish with the passage of time. It is usually enhanced.

Holtz offers an explanation for King’s disappearance in the public prints:

“Fay King gets little coverage mainly because her work straddles two genres. Her cartoon-illustrated column, which she did for many years, was no great work of literature, nor were her cartoons much better than amateur work. However, the combination of the two had an undeniable charm. Her prose was always breathless, like [her description of Girls Will Be Girls] above, but she was so personable in her writings that I’m sure folks of the day felt a kinship to her.

“She was also very up front about her personal life. She certainly kept no secrets about her stormy and at times violent relationship with Battling Nelson, for instance. That sort of thing certainly kept the housewives fascinated when the sat down to read the Mirror.”

Reddit reports that “there is no record of an obituary.”

So Fay King passed away without saying “good-bye.”

“What happened to her?” Reddit asks. “Well, in all probability, she was simply no longer famous enough for her death to be a newsstory. There’s almost no known record of her after the 1930s, although she was apparently still drawing comics.”

Or so we assume. We assume that cartoonists go on drawing cartoons. Cartooning defines them; and they define cartooning. And so they go on together.

|

|

|