|

ANOTHER CONVERSATION WITH WILL EISNER And with Shelly Moldoff about Bob Kane

OVER THE YEARS SINCE I MET WILL EISNER in the early 1990s, I interviewed him several times. What follows here is the raw, nearly unedited transcript of a conversation we had May 16, 1998 during a breakfast we shared at the Motor City Comic Con in Detroit. It was from this conversation that I subsequently pulled articles about Eisner’s inventing instructional comics (see “The Art and Industry of Comics” here in Hindsight for December 12, 2015; and the obit, also in Hindsight, January 18, 2005). While some of this interview will therefore seem repetitive, parts of it are not: at the end, for instance, Shelly Moldoff dropped by our table in the hotel restaurant and told a revealing story about Bob Kane. And the interview includes insights not disclosed elsewhere. Moreover, as a nearly unedited record, this interview reveals aspects of Eisner’s personality and persona. The restaurant was noisy, as most restaurants are, and there are parts of our conversation that I couldn’t understand when transcribing the recording; whenever this happens, slashes appear ////. This is the second of five special Hindsights we’re posting to honor the 100th anniversary of Eisner’s birth. The first, “On the State of the Art and Other Thoughts,” was posted April 2017.

Harvey: You said there were three cartoonists who influenced you. Would you repeat that information?

Eisner: Milton Caniff, Elzie Segar, and George

Herriman. Each man represented a source of instruction. When I talk about

influence, I think of these people as teachers.

Harvey: People think of Popeye as being a terribly active character, but there would be weeks when he didn’t hit anybody. Coming back to Herriman, as you say, he changed the background, but despite that, he could keep the story out, so to speak, and keep it together even though the visuals were changing in front of you.

Eisner: Absolutely. That struck me very early on. Most of these men were very much a part of my literary education, if you will.

Harvey: In essence, what you learned from them was really how to do your craft.

Eisner: I learned my craft from them. When people ask which were the most influential, literally, that was it.

Eisner

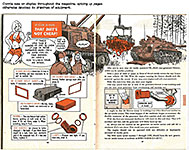

gives Harvey some of the illustrative material from P*S magazine.

Harvey: How recent is this material?

Eisner: Quite old. I’d guess in the sixties. We were very successful. I consider this a very important part of my career because as you know I’ve always believed that this medium--sequential art--is capable of dealing with subject matter far more broad, far deeper, than the simple stories we have today. But also you should understand that I felt that this was a truly great instructional tool. I learned of its value in the army actually, when I was in the military in World War II. I stole the idea of using comics [in my post-war career] /// it was so successful that when the war was over, I formed a company called American Visuals.

Harvey: When you went into the service, did you have any idea that you would be doing artwork in the service?

Eisner: No. When I was drafted, I asked for ordnance--I dreamed of being a foreign correspondence, of getting overseas and be a military correspondent, work on the military papers or something like that. At that time, you had no choice. A lot depended upon the IQ test. At that moment, ordnance was in need of people with skilled backgrounds. When I got to camp and was going to basic training, I had no idea of what I might be doing; I kept asking for an overseas assignment. You must understand that it was not like the Vietnamese War: you felt a calling to serve in World War II. Also as a twenty-two year old, I wanted adventure; the army does that for you. But while I was in basic training, into my tent one day walked two soldiers; both of them were working on the camp newspaper, and they said, We heard that a well-known cartoonist was on the base. At that time, I had been syndicated for several years, and I was an established professional, and the camp was in Aberdeen, near Baltimore, and the Baltimore Sun was carrying The Spirit. And they needed a cartoonist for the camp newspaper, and of course, I jumped at it because it got me out of scut duty, kitchen patrol and so forth. And then from there--Aberdeen is a training camp.

Harvey: Did you know Vic Herman? [Herman, a commercial artist and cartoonist, invented Winnie the WAC, the only female WWII character. For the whole Herman story, consult Harv’s Hindsight for October 2014.]

Eisner: Yes--I got Vic Herman a job on the paper. I knew him quite well--before the army. I knew him from New York--in fact, he had an office in the same building--and he was in Aberdeen and in danger of being shipped out, and I said, I’ll get you transferred-- at that time in Detroit, where we are now, there was an ordnance office. It was decided to base it in Detroit because at that time the Ordnance Department was almost all automotive, and so here, they could go to an automotive shop and look at the machinery. I got Vic Herman transferred out here.

Harvey: He produced a cartoon panel--

Eisner: Winnie the WAC. It was very special.

...

Harvey: Did you say that you had produced a couple samples?

Eisner: I had talked with them about it as a

selling point, and then I’d forgotten about it. And then it came to the

attention of General Campbell--and you know how they did things then: he said,

Get that fellow up here. And I came in to Washington as a warrant officer, not an

enlisted man. And then I became the editor of Firepower, an ordnance

journal, using this Joe Dope character, and then this Army Motors magazine.

/// Also I was producing comic strip material for other maintenance

publications. I’m proud of the fact that the first comic strip on the page explaining maintenance appeared in an Army manual, and I had a terrible fight getting it in there because the adjutant general in charge was horrified of comics. What’s happening to the army? We were causing a revolution in communication. The magazine--the language we used was GI language. For example, the normal army manual would say, The mechanic should remove all foreign matter from the fly wheel. We would say, Clean the crud out of the fly wheel. My approach was that comics were very instructive. And it gave me a chance to spread my wings on something that I firmly believed in--religiously. I always have--ever since I started in this business. The medium is capable of much more than we use it for.

Harvey: Once they accepted the idea that they were going to use comics in an instructional mode, did they present you with the army manual texts and then you would decide from the text how to treat the subject, and then you would rewrite it as well?

Eisner: Pretty much. We would start with a stack of articles written by engineers about part of the engine and the maintenance of it. I would take it and break it down, rewrite it, it would have to be rewritten because I would have to reduce what was to go into balloons and what was to go into narrative. I realized I was good at it because with my limited knowledge, if I understood it, then anyone could understand it.

Harvey: You can say limited knowledge but you had to --not just any cartoon artist could have come along and done this. You had to be able to read a technical manual and say, I understand this; I understand what they want to do. Of course, admittedly, an army technical manual was written to be read by army people, so they weren’t atomic science theory.

Eisner: I wasn’t converting a technical manual. I was working from an article written by an engineer concerning a procedure, a field maintenance procedure. And the engineers of course wrote in their own style. For example, the common struggle we had where the engineer would write, The wingnut may be tightened to a certain degree. It took me awhile to learn that I couldn’t use can instead of may because can meant something totally different to an engineer. It may be tightened but not necessarily can be. I learned a lot-- my skills centered around my ability to envision the procedures. What I would do is go past the theoretical and get right to the procedure. I’d digest the article into steps to be taken. I would cut through the theoretical stuff and visualize what someone had to do. I was very proud of this work; and it gets a lot less attention than most of my other work. For awhile, I was number one in Europe being villified by a bunch of cartoonists who said I was teaching people to kill. I was a merchant of death. Actually, I was proud of the fact that I was teaching people how to save their lives. The rewards-- I used to make a lot of field trips overseas into combat zones-- during the Korean War, and I remember walking into a shop, big mechanic came over to me and shoved his big paw into mine and said, Thank you very much: you saved my ass. And he said that I had explained something that nobody had ever done quite that simply. He said, I got no time to read them manuals--I’m fightin’ a war here. And I remember it because every once in a while something happens that reinforces what you’re doing and tells you you’re going in the right direction. Like going down a dark road and finding someone who says, finally, Yes, this is the right direction.

Harvey: Yes, right. So you were in Washington doing two or three military magazines or journals until the end of the war.

Eisner: One was Firepower, Ordnance /// I was the editor of that. And then I contributed to the magazine called Army Motors. It was The magazine. P*S magazine was the successor that I did after the War. I did that at the beginning of the Korean War. I was then a civilian, and I took an army contract to do it.

Harvey: So the experience-- Firepower, you were editor of that-- did the magazine have text as well as pictures?

Eisner: It was essentially a text and pictures magazine. It had no cartoons in it.

Harvey: So the pictures were photographs.

Eisner: Photographs and paintings and I did a few drawings, illustrations and so forth. Little articles really more inspirational. It was a trade journal. I put it out of Washington. Had a WAC and another guy. In fact, he was one of the editors of that camp newspaper that originally walked into my tent and asked me if I would work on his staff. And when I got to Washington, I had him transferred. By then, I had some muscle. I had him transferred to me. Harvey: How often did Firepower come out?

Eisner: It was bi-monthly.

Harvey: And then you were contributing to Army Motors. And that had cartoons. And so this showed you the potential of the medium for something other than literary entertainment.

Eisner: I believed this kind of thing could be done, and this gave me the opportunity to do it, to show that it could be done. War is a terrible thing, but it does some wonderful things, too. Because of the desperation of the military to get things done, they’ll undertake highly experimental things. Really, they had no choice: if I could prove it would work, then they would do it. It gave me a chance to try something which probably under peacetime conditions I could never have sold to anybody.

Harvey: Were there any other instructional comics at the time that were very extensive? I can imagine that comic books might have features about how to build an airplane model or something, but--

Eisner: No, no. There were a bunch of comics done on military courtesy, discipline, inspiration--that sort of thing. Instructional comics fall into two areas. One is what I call attitude conditioning; and the other is instructional, primarily procedural. How to do something. Al Harvey produced some on military courtesy. Then they used comics sometimes as propaganda: they’d fly out and drop them on the enemy. That was in another division. I was concerned purely with comics as an instructional tool ... ////TAPE ENDS/// During the war, there were dollar-a-year men, people from US Steel and people of that sort, these large companies provided these people as technical advisors. These were guys-- General Motors would contribute as liaison between industry and the military. It was very important to the military, particularly the Ordnance Department, to secure the cooperation of the manufacturers. I remember standing in the office of the Chief of Ordnance once, he was on the telephone talking to the company that made radiators, trying to argue them into converting their production line so they could make military hardware. They were very, very reluctant; they said, Well, gee, we do that, and the war is over, and we’re out of business. Anyway, when the war was over, I got a call from the guy from US Steel, who had been one of these dollar-a-year guys, and he said to me, Are you still doing that instructional stuff? And I said, Yes. I wasn’t, but I was a New York boy, and you don’t let opportunities go by: you instinctively learn that you don’t say No. So I said, Yes, and he said, Well, we could use something like that in our employee relations department. Then we got to do something for General Motors. So I started the American Visuals Corporation to produce instructional comics of this kind.

Harvey: You were also doing The Spirit in that weekly comic book supplement for Sunday newspapers. Were the same people doing both?

Eisner: No. I had other people working on the American Visuals stuff. But it was getting very, very busy. I had to make a decision at that point. I started looking around to see if I could find someone who could continue The Spirit for me. I couldn’t find anybody who could emulate the style to my satisfaction. I had Jules Feiffer, who could do some writing. I tried Wally Wood, and that didn’t work out. He was so totally different. I learned something then. I learned that there were certain comics that cannot be continued because they’re so closely associated with the author. At that time, I tried it, but I finally had to make a decision. I realized that the future of The Spirit was not that great. And I believed in the future of instructional comics. Two things: first, newsprint was going up in price. And the price we had to charge for the supplement was getting too high. The thing was only fifteen pages, and we couldn’t sell enough advertising in that section to make it pay. So I realized that sooner or later, it would have to stop. I

could have done a daily strip, but candidly, it didn’t engage my interest.

Doing a daily strip to me is like trying to conduct a symphony orchestra in a

phone booth. I got no real satisfaction from it. I did a daily Spirit for awhile before the War, and I did one strip where the whole thing was

footprints across a stretch of snow, and editors would say, What are you trying

to do?

Harvey: People at the Con here put me in a corner where all the models are. [In those days, I was selling lewd lady pin-ups in Artists Alley.] Brinke Stevens and others I’ve never heard of.

Einser: [Laughing] And all the while, you’re yelling, Don’t throw me in the briar patch!

Harvey: [Laughs] It’s fascinating to watch these women-- I think every woman knows that her body and appearance is a matter of considerable interest to the male population. And it’s interesting to watch these people who are making their living that way. It’s not just a question of being attractive, of being female. This is something they do for a living. I always wonder what’s going through their heads.

Eisner: Well, I’ll tell you what’s going through their heads. They’re like athletes. The athlete knows he can hit a ball four hundred yards; he’s good at it. I know for example that I can draw. I have the skill in the hand. As an interesting sidebar, where I live now [in Florida], I’m living with a lot of people in the autumn of their lives. There are a number of women there who at one time were very beautiful; one of them was a model. She’s now seventy years old. And they try to hang on to their appearance. They do it in funny ways. They have face lifts. They wear their hair like they did in the old days. The use of cosmetics. Trying to hang on. One of the things I’m trying to work on now, I’m trying very hard to see if I can convey these ideas. An author [who works with words] can easily say in his text, He regarded himself still as a super model. But how do you show that with images? And this part of the task I’ve given myself.

Harvey: And how do you do it with some measure of subtlety? Because a visual medium is not subtle.

Eisner: Very specific, too. There’s no formula I can advance. Human emotion is expressed not necessarily by faces. A lot of young cartoonists who were students I had always concentrate on faces to show emotion. But they don’t realize that emotions are displayed by body posture and gesture, too. So you can show-- An example I used in the classroom, I showed them the back of a man. And I’d show him in two or three poses, and I’d say, Now, which pose shows that he’s happy with himself; which one shows that he’s defeated and very depressed. Which one shows that he plans to //// This is a back view, now--so only body language can express emotion. I did that in Contract with God, for example--the old man in the opening scenes walking through the rain. I tried very hard to show-- and in this book I just completed, being published now, Family Matter, I spent a lot of time dealing in postures.

Harvey: You in effect started American Visuals in response to this US Steel guy phoning you with a job. And then the work you were getting through that became demanding enough that you had to decide, Am I going to do this or The Spirit?

Eisner: The competition was tremendously great. I was expanding into industrial comics, the use of comics /// And it just became too much. It’s like any company that decides to drop a division that doesn’t seem to have as much promise as some others.

Harvey: Were there other companies then doing instructional comics?

Eisner: Oh, yes--I don’t know who they were, but there were some people doing stuff for General Electric.

Harvey: Do you think all of this--all the other companies--came out of the military environment?

Eisner: No, I don’t think so. But I don’t know. May have.

Harvey: Before the war, were there any instructional comics being produced commercially?

Eisner: There weren’t instructional comics, but there were comics used as commercial products, for example, there was Mr. Coffee Nerves. Strips that were specialized as advertising vehicles. But they weren’t procedural. For example, I did a book for General Motors explaining the changes in the Social Security law. And we did some attitude comics, too. Another time for General Motors, I got Jules Feiffer to do one on What Makes the Boss Tick. They turned it down. The salesman came in at the time and said, You’re running a soup kitchen here for all your old comic friends here. Then about two months later, Jules hit it with the Village Voice. And the salesman said, Hey--what happened to that guy?

Harvey: This kind of thing [looking at some examples of instructional cosmics from P*S magazine] lends itself to comics treatment. [Columns of panels comparing, for instance, Dos and Don’ts; the columns show approved and disapproved behaviors side by side.]

Eisner: How-to thing.

Harvey: It really --it’s something that comics can do very well.

Eisner: The guy that helped me tremendously was Klaus Nordling; he’s dead now. He worked with me on it. Also Andre LeBlanc.

Harvey: Did they do drawing and writing?

Eisner: They did both. I invariably laid it out. I did the cover, for example.

Harvey: After awhile, somebody who’s worked with you for awhile will know the habits of your thinking.

Eisner: Oh, yes. They adapt to it. They understand the basic principles under which you work. And they come out with stuff that conforms to the standards.

Harvey: For the last maybe thirty years of Steve Canyon, Caniff was assisted by Dick Rockwell, who did the pencils. And people would protest--saying that Caniff was giving up the essential part of composing the cartoon. But Milton wasn’t giving anything away. And if you saw Dick Rockwell’s pencils, you knew that. They were very sketchy.

Eisner: I know. My office in White Plains was a kind of trading post. Dick would bring the pencils down to my office to ship them off to Shel Dorf, who did the lettering and then sent them to Milton.

Harvey: And they were very sketchy. Dick told me once that he liked to give Milton a lot of lines to choose from. Well, anybody who followed Caniff’s work in comic strips for any length of time knows that there’s a certain pattern that he often followed. And he could easily accept that same pattern when presented to him by Rockwell. But he would sometimes change it. If he didn’t like it, he would fix it.

Eisner: He had the final word, retained control.

Harvey: How long did-- The Spirit stopped in 1952. And by then American Visuals was going full speed, I assume. How long did you keep that going?

Eisner: American Visuals --until about 1971, 72. I had a number of little companies. That kind of thing kept going until about 1971, 72. At that time, I gave up the army contract, P*S magazine.

Harvey: So when you started American Visuals, you went after one big contract, P*S magazine, that would keep bread on the table so to speak while you looked for and worked on other projects.

Eisner: A contract large enough to be able to provide the basic core. The marketing of an industrial or instructional comic is very difficult. There’s a huge gap between the proposal of a project and the sale and then the execution of it. And you need enough financing to pay salaries and keep the office going while all this comes in. Financially it was profitable, but it was very hard to manage it. You couldn’t market stuff the way you can popular magazines. You don’t have newsstands; you don’t have agents. /// It was very successful while it lasted.

Harvey: [Looking

at samples.] Here’s Joe’s Dope. This come out of WWII stuff? Looks like

later?

Eisner: Later, P*S magazine. Originally, Joe Dope was created for Army Motors. Sergeant Half Mast was created for Army Motors. The remarkable thing--Joe Dope and Beetle Bailey. That’s not to say that Mort Walker copied it or anything, but given the same problem, two separated by miles came up with a similar solution.

Harvey tells about DNWITS in the Navy. The initials DNWITS appeared in the blanks of test papers at training installations; it means Do Not Write In This Space—because the test papers would be used again and again. Harvey invented a character named DNWITS (“dimwits”) who appeared in some Navy publications.

Harvey: Not only was it the name of the character; it described the character!

Eisner: That’s because you’re geared to that kind of thinking.

Harvey: [Looking at samples again] What was the period here? After the war?

Eisner: Yes, after the War. P*S magazine ran from 1950-something-- in fact it still exists. Other people have taken it over.

Harvey: Oh, here’s the sex appeal. Connie Rod. What’s that mean, Connie Rod?

Eisner: They’re named after parts of the engine. Connecting rod. Sergeant Half Mast sounds like half-assed. Half Mast Mechanic.

Harvey: [Pulls out copies of P*S Magazine that he has] Recalling the story of the mechanic who said you saved his life because he didn’t have time to read the manual, you can tell, looking at these magazines, that they can be read by people without much time. Small stories. Little boxes, illustrations, and so forth.

Eisner: Remember that images remain in your mind. When you write a description or a phrase, the reader has to convert that into an image, and that is the thing that remains in his memory. Images are the things that remain. We never used photographs. Just drawings.

Harvey: And the pages-- if you just look at them-- here’s one: there’s enough visual interest here that you’re not put off by the gray matter.

Eisner: Exactly. Harvey: So some guy who doesn’t have time to do a lot of reading, he can take this--read one little bit.

Eisner: The amount of text in that, proportionately, is much less than the amount of text in a manual. Also, I should point out that wherever you see technical drawings, the perspective is taken from the person who might be looking at the machinery. That’s one of the rules that I set up at the shop. If you’re going to show a procedure--like the removal of a gasket from a part--the reader must see it exactly as a person who is doing it would see it. From that angle. The tendancy in technical manuals is always to show it from the technical perspective. But we would show it from the point of view of the person working on the machinery.

Harvey: Makes perfect sense.

Eisner: Well, it does.

Harvey: But a technical artist, a draftsman, wouldn’t have thought of it.

Eisner: No. He’s thinking in terms of the technology. P*S was very successful. The circulation was about a million copies. But the great testimony to its success is the fact that it’s still going. Almost fifty years. Murphy Anderson ran this for awhile too. What happened --contracting it out, the lowest bidder got it. That reminds me of the joke about the astronaut, John Glenn--who said that the scariest moment in his career was when he sat in the cockpit of that spacecraft and realized that every part in it was built by the lowest bidder! [They laugh] Makes you wonder.

Mike Ploog--hired because his stuff looked like Eisner.

Eisner: His style was essentially like mine. Also he had extensive military experience. //// Good military know-how. I remember once, talking about his style, a kid asked him, Did you learn your style from Will Eisner? And he said, Hell no, I had my style long before I met Will Eisner! [They laugh] Kept the army contract from 1950 until 1972. Murphy had it after me. [Actually, someone else won the bid after Eisner and before Murphy but lost it.] By then I’d acquired a company producing inservice training material for teachers, and we were selling to schools. /// About a year or so later, I sold my stock in the company that we’d acquired--had an opportunity to sell it, and so I did. Then sat around, jingling the coins in my pocket [grins] trying to decide what I wanted to do. At that time, I got a call from Stan Lee, and he said, Are you out of work? And I said, Yes, I’m at liberty. So he said, Come down and we’ll talk. He wanted me to replace him at Marvel; he wanted to go out to California-- at that time, Marvel was hoping to open a Hollywood division-- he was in love with movies. I love the movies, he said. I remember that. But he told me, They won’t let me go until I can replace myself here. Somebody to replace me. And you’re the only guy who has any business experience as well as artistic ability. We had a long lunch. And that was the end. I thanked him very much. And we were walking out to the elevator, and he said, Why aren’t you interested? I said, I think it’s a suicide mission. Really wasn’t for me. I was in good shape financially. And in 1974, I began A Contract with God. Harvey: About then, you’d run into Denis Kitchen.

Eisner: Yes. I ran into Denis Kitchen in 1971 or 72 at Phil Suelling’s convention in New York. That’s a funny story, too. At that time, I was CEO of this company up in Connecticut, and I was sitting in my office--I was a suit!--and my secretary walked in, and she says, There’s a phone call out here for you--a Mister Suelling, and he says he has a comic convention. And she said, Are you involved in comics at all? [Harvey laughs] It was like admitting that I once had been a drug addict! [Harvey laughs] And I said, I used to be a cartoonist. And she said, Really!

Harvey: What did you draw, she asked.

Eisner: Anyway, Phil got on the phone, and anyone who knew Phil knew that you had to hold the phone about a foot away from your ear-- he talked that way. Listen, he said, I’ve got a convention down here in the city; you’ve gotta come down. I don’t care what the hell you’re doing; you’ve gotta come down. So I said, All right--I’ll come down. It was in the Biltmore--no, the Commodore Hotel. I came down there, and I saw all these kids collecting comics--fat little kids with acne, fat old guys--and they wanted to talk about the Spirit. And I thought the Spirit was dead. I had nailed his coffin shut years ago. This is 1970 as against 1950. Who the hell would be interested? And I ran into Art Spiegelman, a couple of other underground guys; and I met Denis Kitchen, and he asked me if he could publish a couple of Spirit stories in his underground magazine. And I said, Tell me about the underground. He had a straggly moustache; all these guys had long hair. And they all smelled of some kind of aromatic cigarette. I don’t think Denis did. Anyway, after I left that meeting and came back to Connecticut, and I was on the train, and I realized, My god--these guys are revolutionaries. They’re doing with this medium what I always believed it could do. They’re doing literature--protest literature, but literature. It stayed with me, and about a year later-- It was one of those things that happens that reaffirms an underlying nagging belief that you have. So I realized that this was still a worthwhile medium. So I started doing A Contract with God. I believe the big revolution in comics--

Harvey: In the late sixties. You’re talking about underground comic books.

Eisner: Oh, yes. Sixty-eight, sixty-nine--seventies. The Freak Brothers, Gilbert Shelton. Crumb. Spiegelman. Moscuso, Spain. These guys were using comics as a true literary form. For the first time, I realized that they had picked up something --they were doing something-- using the medium for protest, they did it in their own way, and as always when people are making a revolution, very few of them are thinking about the long range potential. They’re doing it to satisfy their own needs. But they were using comics as protest literature--as literature. They thought they were being entertaining. They were doing it for the jokes. They were doing it to make a few dollars so they could buy pot or whatever. But they were using comics --it reinforced my beliefs, as I say.

Harvey: There was a period in the sixties when you were working for Bell syndicate?

Eisner: I was president of Bell-McClure. Harvey: How long did that last?

Eisner: That was about a year or two.

Harvey: Were you maintaining American Visuals at the same time?

Eisner: Yes, what happened during that period is that I joined-- we merged with a company called Kostergan [sp?] Corporation-- they were on the stock market, producing materials for reading racks in industrial places. American Visuals began producing stuff for industry, and we were growing very rapidly, and we discovered that there was a market for employee relations reading material. So we began selling to that market, but we were getting very successful. What we did instead of publishing a booklet and then going out and trying to sell it, we installed in the shop a couple of small multilith presses, and we printed maybe a hundred copies of a booklet. And then we visited a hundred companies and took orders. And then printed a hundred thousand, three hundred thousand--whatever was necessary. Kostergan was publishing what they thought would be a good thing, and then very often they’d wind up with a large inventory of booklets they couldn’t sell. So we were kind of a gadfly, pressing hard on their heels. The president came to me through my salesmen--we had a lot of clients--to talk to me about merging. So we negotiated and we decided that we’d merge. And I was the largest stock holder; that’s why I was president. I didn’t have total control because it was a publicly held company; but I had a lot of muscle. Anyway, we acquired --because we were involved in newspaper-like stuff-- it made sense to acquire a newspaper feature syndicate, and that’s how I became president of Bell-McClure. I was there a year or two. And then the stockholders wanted to boom the stock; they weren’t interested in any of our objects. And I couldn’t see it. I was too young to die, and two old to waste my time. So I bought my way out--sold my stock. And continued American Visuals Corporation. That’s my commercial history. A side of my history that most people at these comic conventions never heard of.

Harvey: While you were president of Bell-McClure, I tried to sell a comic strip there, and I’d swiped at least five panels from The Spirit, thinking no one ever knew who did comic book features.

Harvey’s

story: After I got out of the Navy in 1963, I produced a presentation booklet

for a comic strip that I hoped to get syndicated. It was a comical adventure

strip called Fiddlefoot [the history of which is regaled elsewhere in Hindsight for July 2012].

In that classic manifestation of sincere flattery that infects popular culture

generally, I swiped from a Spirit story in Police Comics No. 96 three or

four images for my presentation booklet. One of my scenes employed the highly

distinctive oval skylight of the Spirit's residence in Wildwood Cemetery.

That summer, I entered graduate school at New York University, an institution I'd chosen because it would permit me to make the rounds of syndicate offices in the city while I was matriculating there. I left my presentation book at one syndicate after another, in succession, returning after a week to get the verdict and to retrieve the booklet—King, United, and Bell syndicates. No one bought the strip. At King, they were simply not buying anything, they said: they explained that if they bought it, the only way newspapers would pick it up would be to discontinue another King strip, so it seemed pointless to undertake it. At Bell, however, the rejection was accompanied by an unsettling comment. When the factotum there (whose name I've forgotten, if I ever knew it) returned my presentation booklet to me, he asked, casually, if I'd ever seen Will Eisner's Spirit. I knew, of course, what prompted the question. Caught, I did what any culpable criminal would do: I lied. “No, heavens,” I exclaimed, “—what was that name again?” Who, among the living, would have seen that old comic book? Some years later, I discovered that Eisner was, at the time I dropped off my presentation booklet, president of Bell Syndicate. When I met Will in the flesh nearly thirty years later, I told him this story, and we both laughed about it.

Eisner: Big fat guy? Looked like a summo wrestler? Osenenko was the operating head; I was the president, but I didn’t see what came in. I ultimately passed on features, but actually I wasn’t doing the buying. He’s dead now-- he told me something-- When we left the Des Moines Register, it didn’t sell. And he said to me one day, You know--this strip is about twenty-five years ahead of its time. Someone asked me yesterday to what I attributed the enduring success of The Spirit, and --

Harvey: You’re just twenty-five years ahead of your time is all!

Eisner: You’re talking about it now made me think of that remark. Osenenko was a very able editor. Can’t remember his first name.

Harvey: If you had something to say --what would you tell somebody about the future of instructional comics if someone wanted to get into it. Is there a trick to it? An attitude you have to assume?

Eisner: From a production point of view-- there are two levels: selling and production. You gotta find the customer, gotta find purpose for it-- producing a comic strip with instructional purposes, you need to produce something readable and understandable. Actually, the formula for doing it, is to work the procedure out in your own mind, how you would do a thing--like how you would tie a shoe lace; you go through the steps. Then you edit those steps into the amount of space you have. One of the problems with comics is that you need a lot of space. If you are doing words only, you can do the whole thing in a page, or a single paragraph, but it would take two or more pages of comics to do. Selling --it’s a very hard sell. Very few people can afford to do it. The attitude generally is, This material is for idiots. The other day I got a bunch of stuff being done by a young man out in Pennsylvania somewhere. He’s operating a little commercial kind of thing-- doing pretty much what we used to do. The field is still there. But it’s a hard field to sell into because there is no structured marketplace for it. You have to go to the industrial companies, convince them that they need it-- One of the hard things I found in the selling of this is that you’d come to the manufacturer of a item and you’d say, Really, you should include with this machinery a better manual than you have here. You have only a skimpy one. But the manufacturer says, I don’t know that I need this thing: after they’ve bought the thing, what concern is it for me? What difference does it make if it’s a good manual or a bad manual? You find that kind of thing. You have to convince them to spend more money to do this. A lot of manufacturers just do a typewritten sheet; why spend a fortune doing a special illustrated manual?

Harvey: And they’re shortsighted because they’re not seeing the next thing they might produce that some of the same customers might buy if they had faith in the company, if they liked what had happened to them before.

Eisner: That’s the problem. I did succeed in selling -- a South American company, and the Germans were outselling them simply because they had better manuals. And they could understand that. They finally zeroed in on what was needed. We did the manual for them.

Harvey: Several significant problems here. You have to find a manufacturer or supplier whose product could be improved with this kind of treatment; not everything would work. Then you have to figure out how to do it, how to treat it so it will be better or more salable. And then you have to sell the manufacturer on it.

Eisner: Usually, it took six to eight months to consummate a sale. First of all, we had to make a dummy sufficiently comprehensive so that they manufacturer would understand what we wanted to do. In order to get them to consider a dummy, it took a couple months of selling, convincing somebody. In a large company, the person in charge of manufacturing isn’t very often the same fellow whose job is to produce the literature that comes with the item. Sometimes, it falls into the hands of a public relations director; sometimes, who knows? Most manufacturers don’t have a structured area for it. So by the time you finally get a contract to produce it, the price that you have to charge has to contain enough to pay for months of development, wages for everyone, salesmen and so forth. That was one of the problems we had. We’d have a staff of people, and we’d have to pay them while we waited for the contract to come in. I had a staff of about eight salesmen at the time on the theory that if you have contracts in the hopper, you’d get them back enough to pay for everything. But it wasn’t all that rewarding. The dollars look very big in the gross, but when we netted it out, we found that we spent an awful lot of money in that period paying salesmen advances against commissions and salaries of an art director while we waited.

Harvey: It’s amazing that you could do it at all.

Eisner: Well, we did it for awhile, and then we ran a cropper for awhile. American Visuals--one division got into trouble. We had contracts with oil companies and others. We did service manuals. All sorts of companies. Also what happens, is that there is no real long range control over anything. It’s not like a magazine where the readers are voting on it everyday. The guy working for General Motors has no voice in what happens next: he gets the manual and he may like it, and he may tell his supervisor. Not often. I don’t mean to discourage people from going into this thing; but those are the realities.

Harvey: I suppose at one point instructional movies were not accepted either. I suspect that as comics acquire social status as an art form, then there’s going to be --it’ll be easier to get into the instructional field.

Eisner: It’s a hard to get into an accepted status. I’m struggling with that right now with this new book, Family Matter, which is really aimed at an adult audience. All my books are always aimed at an adult audience. Big joke in the industry is that Will Eisner draws comics for people who don’t read comics. [Chuckles] I’m coming to the conclusion that the presence of a speech balloon seems to be the trigger that turns people off--or at least, they use that as the identity symbol. If there’s a balloon, it’s comics; and if it’s comics, it’s for kids or idiots. And I can’t take this seriously. Just look at it. I don’t know what we can do about it. Feiffer solved the problem by having no balloons--just words alongside heads; and that seems to make it more acceptable to an adult audience.

Harvey: You told me that once before. And when I was driving back to my motel, I remembered the first time I saw Feiffer’s cartoon--I was in college at the time--in the Village Voice. And I remember thinking, This is different. There’s something--it looks like a cartoon, but it’s not quite a cartoon. So I think you might very well be right.

Eisner: I’ve got another thing on the boards that I’m working on. A collection of memories of real incidents that happened to me. And I did this with no balloons. Just words floating next to speaker’s heads. I don’t know whether that’ll help or not.

Harvey: Is this the collection of stories about Vietnam?

Eisner: Yes, yes--did I show that to you?

Harvey: Yes, and I thought it was very successful. [See Hindsight for April 2017.]

Eisner: Well, I hope it’ll work out. Actually, that’s the only solution. And it works only on matter where you have a whole set of dialogue coming from one person; I don’t know how you could eliminate the use of the balloons in other situations. I’m counting heavily --since 1974, I reasoned that all the people that started reading comics twenty years before are now 35 or 40 years old, and I asked myself, Would they continue reading Superman and Batman? Would there be enough for them? Would the storyline be satisfactory? And I reasoned that perhaps they would now be interested in stories of a different sort. I was partly right because A Contract With God is /// TAPE ENDS /// --the thing that keeps me going is the fact that someone says, I got your book and I love it, and I read it two or three times over the last few years. And that’s great. That book’s doing what I want.

Harvey: Justifies your faith in the medium. Somebody’s coming to pick you up?

Eisner: At 8:15 a.m. We have about a half hour more. Maybe you’ve exhausted all your questions.

Harvey: I don’t know whether I have or not, and won’t until I get home.

Eisner: I usually leave an interviewer lying on the ground, breathing heavily. Very few interviewers survive an interview with me. [They both laugh]

Harvey: Who’s doing P*S magazine now?

Eisner: I don’t know. One of the things I’m very proud of is the fact that I was able to --it doesn’t come to people too often that they can introduce a new concept and have it stick.

Harvey: Well, you’ve introduced two or three new concepts and had them stick. [Eisner chuckles] You’re something of a collossus figure, towering over the medium--having done successfully so much, having innovated so much of the medium yourself.

Eisner: I’d like very much to agree with you. [Laughs] You may be right. [Laughs again]

Harvey: I don’t think there’s much question. You were there when comics were getting started under circumstances that were --

Eisner: A lot was just being in the right place at the right time.

Harvey asks him to draw a floorplan of the Eisner-Iger shop. Entrance, front office, then the big room, with Eisner’s desk at the “front.” Rolltop desk, he said. And he sat with his back to the troops. Kirby met Meskin there probably.

Shelly Moldoff comes by.

Moldoff: Don’t get up, don’t get up.

Eisner: I can’t.

Moldoff: Anyhow, I’ll see you at the Con.

Eisner: I’ve got a late panel today. I’ll be sitting around signing autographs, kissing babies and so forth. Are you going to be doing a panel?

Moldoff: Yes, the Superman birthday panel. Nice group. Murphy is here.

Eisner: Yes, I had dinner with him last night. Not too many of them left.

////

They talk about Bob Kane, who’s mother was, apparently, very protective.

Eisner: When I knew him--in high school--he was always sick. His mother used to say--

Moldoff: Always babied him, always. Eisner: --don’t take Bob out because Bob’s not feeling well now.

Moldoff: Always had an afternoon nap. He was always taking a nap. With his Playboy magazines and his girlie magazines. Eisner: He has a wonderful story [to Harvey] I have to tell you about. I often tell about him and Bob Kane and that lunch? [To Moldoff:] I envied you because over the years I used to double-date with Bob when I was in high school. He never had any money; I always wound up paying the bill.

Moldoff: I ghosted for him for fifteen years. I came up to New York on business once--I had already moved to Florida. This’ll only take a second. And I went to the city, and they told me that Bob’s mother had died. And I knew her since I was sixteen. So I said, I gotta call Bob and tell him how sorry I am. So I called Bob, and he said, What are you doing here? And I said I’d come up from Florida, and I found out that your mother died, and I just wanted to talk to you and say I really feel bad and I’m so sorry, you know. He says, Well, I miss her a lot; let’s have dinner. I said, No--I’ve got a busy schedule. And he says, No--I insist. We’ll have dinner. Friday night. So Friday night, I went in, I meet him at his apartment, we go down a restaurant and have a nice dinner, and when we finished dinner, he reached in his pocket and stopped. Shelly, he said, I forgot my wallet. Even in a taxicab if he was driving with somebody, he’d say, Oh, I gotta get off here; sorry. And he’d get out and leave you stuck with the cab fare. So I said, You don’t have any money, Bob? Because I don’t have any on me; I left everything in the car. I told him, I left my wallet in the car--I locked it in the trunk. But if you wait here, I’ll go get my wallet. It’ll only take a minute. I go--and I never came back. It’s the last time I ever saw Bob.

Eisner: I’ve told that story forty times because it was so typical. I’ve been wanting all my life to do that. Never been able--never had the opportunity. But he [pointing to Moldoff] did it!

Moldoff: Never had the opportunity to do that before.

Eisner: Having dinner last night with Julie Schwartz, and I asked him, Tell me about Bob. ... When we were in high school together, Bob and I used to go out. Bob could always get girls. He used to get beautiful stupid girls--what Al Capp used to call stupid American beauties. You couldn’t talk to them, but they were very pretty. And so we went out--we used to go to Glen Allen casino and listen to Sheffield and his Rippling Metaphors. And so we were out there one night, and Bob got a table for four-- and the music comes on. And one of the girls was very intrigued by the fact that I’m an artist and I could draw. Bob is singing to his date. I didn’t think he had the strength. Anyhow, the evening was over. We’re starting out--and Bob disappeared. I’m stuck with the check. And we get outside, and I said to Bob, Hey, Bob, you know--we were very poor at that time--and I said, You owe me a couple of dollars. The whole deal was only four or five dollars. And he said to me, Yeah--I’ll pay you back. And he never did. And I always said, I gotta get back at this guy. Never did. But he--HE [Moldoff] did, he did it! [They all laugh]

Moldoff: I spent a lot of time with him, and his mother lived near his apartment, and she cooked for him. And very often, she would come in and say, Bob--I met the most gorgeous girl, beautiful girl, blonde, beautiful. And I have her name and address. I told her that my son is Bob Kane, Batman’s creator--and she’s anxious to meet you. Another time, she came in with a card--always bringing in names of girls. And one day, I said to Bob, Tell me--is your mother your pimp?

Eisner: His mother was very good. Bob had a sister. And his mother’s idea was that I was going to marry her. Came close. But I finally extricated myself. I used to visit Bob on Saturdays. He’d go down to the syndicate to pick up artwork, which was only a few steps away in those days--and I didn’t really care about it. //// His sister was always accidentally there. //// She was a female version of Bob. His mother kept pushing on me. And I finally extricated myself.

Moldoff: It’s a good thing. Your whole life could be different. You’d be the brother-in-law.

Eisner: About three years ago, during the height of the Batman movie thing, Julie Schwartz came over to me in San Diego, I was signing books. And he said, Bob Kane’s here. And he put Bob Kane in line for my signing. And when he got up to me, I said, Hi, Bob. What are you doin’ these days? How’re you doing? He said, What do you mean--how’m I doing? And I said, Well, are you making a living? Are you all right? He’s an example of how to succeed without any talent.

Moldoff: He was very lucky.

Harvey: He must’ve had a pretty good deal early on to get his name on Batman and get them to leave it on.

Eisner: Now, that was a lucky break. He ran into a lawyer at a cocktail party at the very moment when the copyright was up for renewal. He sold Batman. I was at his house when he came back and brought his father with him. Bob was working for me at the time. And his father was an insurance man /// And Jack Leibowitz who was Harry Donnenfeld’s right-hand man /// ...the only thing was that as long as the strip continued, if Bob wanted to do the penciling--

Moldoff: Guaranteed work.

Eisner: Guaranteed work. He could always do it.

Moldoff: His father had the good sense to accept the deal.

Eisner: Bob would have accepted it. At that time, it was a good deal. Nobody had a better deal than that.

Moldoff: Jack [Liebowitz] was always very good to Bob. Many times while I was working there, Bob would be short of money. And he’d go to Liebowitz and say, I need an advance--$8,000. And Liebowitz would give him the money. And then he’d say, I’ll take a little out of each check; you’ll pay me back. And Bob told me this’d go on for like three, fourth months; and then, I’ll go to Jack and say, Jack, it’s really taking too much out of the check. And Jack would say, Forget it. And I asked Bob, How often do you do that? And he said, Every couple years.

Eisner: Bob ran into this lawyer at the cocktail party, and the lawyer said to him, You own Batman. Bob said, No I don’t. And the lawyer said, Let me see the contract; maybe I can do something for you. And it turns out that the contract was pretty tight. And that moment--

Moldoff: They were vulnerable.

Eisner: They were vulnerable because they were trying to sell ABC or NBC the campy Batman series for television. And they were on the verge of a contract. The lawyer walks in and says to them, We’re going to sue. They said, You don’t have a case. And the lawyer said, I may not have a case, but I can drag you into court anyhow. And at that moment, they were afraid that the television company in the face of a suit would drop the whole deal.

Moldoff: Hot potato.

Eisner: So they settled by giving Bob a lifetime or 20-year thing, maybe one percent of the merchandise. Which at that point was nothing. Until Batman hit it, and then there was a million, billion dollars of merchandising. And Bob’s one percent was pretty significant then. But he --I have to say this about Bob, he was very thick-skinned. To be able to go out to Hollywood and hang around, hoping he could be the consultant on the movie, and he didn’t own anything, was --took great courage. So they hired him for $50,000 as a consultant on the first Batman movie. They needed a consultant like they needed a hole in the head.

Moldoff: Julie Schwartz and I were talking once, and he said, I saw Paul Levitz last week, and he showed me a check. It was Bob’s bonus at the end of the year. And I said, And he showed it to you? Yeah. And it was for one million dollars. Merchandising is such a deal.

Eisner: One percent of a billion dollars is one million dollars.

Moldoff leaves.

Eisner: I sat with my back to the group, but I’d get up and walk up and down the aisles--like a galley ship.

Soon afterwards, we paid our checks and left for the day’s activities at the Con.

|

|||