Remembering

Clay Geerdes

Championing

Comix and Rational Thought

HISTORY,

THOMAS CARLYLE SAID, is the essence of innumerable biographies. It is the

lives of individual people, which, summed up, make history. A commonplace,

surely. Even Carlyle, that crusty old roaring hairy bear in his high, stiff

nineteenth century collar and cravat, would doubtless agree about his aphorism

being a commonplace. Certainly, the history of cartooning provides a telling

example of the truth of Carlyle's adage: the history of the medium is the sum

of the accomplishments of its thousands of practitioners. One of those was the

late Clay Geerdes. But he did a little more towards advancing the cause of

cartoonists everywhere than simply doodle a few cartoons. And that's why I'd

like to take a few scrolling inches here to consider the man and his works.

Clay

Geerdes, one-time college English teacher and sometime cartoonist, spent the

last quarter of the 20th century around San Francisco Bay as a

freelance street reporter and photo-journalist, covering the hip scene. But it

was as champion of creative self-expression and passionate promoter of

cartooning that he made his mark in the history of comics.

I'd

known Clay for over fifteen years before we met, face-to-face. We started

corresponding in September 1980. We argued, fought and made up. Mostly, though,

we exchanged views on the nature of the so-called American civilization and the

state of the art in cartooning. Usually, we agreed. So in the ways that count,

we were old friends by the time I found myself in San Francisco in the fall of

1995 and rang him up and arranged to meet for lunch.

"You

know the Warner Brothers Store on Market?" Clay asked. "I'll meet

you there."

So

I walked over to the Warner Brothers Store at the appointed hour, and there he

was, wearing trade-mark black and a grin to go with the twinkle in his eye.

"These

are my pals," he said, gesturing around him at Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig,

Sylvester the Cat, Tweetie Bird, Daffy Duck, and Yosemite Sam. "I grew up

with these guys."

And

then, as we walked out of the store past an alcove of animation cels for sale,

came the ever-present Geerdes Reality Check: "These are phonies," he

said. "They make these cels to peddle to fans, but the real cels—the ones

they use to make the films—those are never for sale."

That

was Clay in a nutshell. Part romantic, part cynical realist. And all

maverick, a maverick with a mission.

Clayton

Edward Geerdes, Jr. was born in 1934 in Sioux City, Iowa, but grew to maturity

in Lincoln, Nebraska, where his family moved when he was about five. He dropped

out of school when his father died in 1949. “I was out of control,” he wrote me

once. “I just worked here and there, washing dishes, making sodas and sundaes,

loading trucks; I never stayed anywhere long.” Eventually, he went to work for

Western Electric, “wiring selectors and connectors,” he said. He also went to

classes at night and earned his high school diploma. He joined the Navy in

November 1954 in order to “escape Nebraska.”

“Facing

another miserable Nebraska winter, I was passing the recruiting office one day,

and I just went in and signed up. It was, I thought, now or never. Best

decision I ever made. While I was aboard ship, I read most of the books in the

small ship’s library, and by the time I was mustered out in 1958 I was ready to

take on college life.”

For

part of his tour in the Navy, he aboard the USS Chemung, a tanker that cruised

the South Pacific, including ports of call in the Phillippines, Taiwan, and

Australia. When his enlistment ran out in 1958, he was stationed at Treasure

Island in San Francisco Bay, so he entered San Francisco State College, where

he finished work on his Master's degree in 1963. While a student, he married

for the second time—to Shirley, in 1961 (they divorced in 1970); his first

wife, presumably a Nebraskan, was named Judy. I never found out any more about

either. Clay had a daughter with Judy, and she, going through a pair of

husbands, had a daughter.

Clay

began work on a Ph.D. at the University of California at Berkeley, and although

he finished his dissertation, he did not complete the course work before the

need to earn a living loomed larger than academic objectives. He started

teaching English at Fresno State College (1965-68) and continued at Sonoma

State College (1968-70).

Caught

up in the Free Speech Movement of October 1964, Clay soon lost interest in

doctoral programs because they no longer seemed relevant. In 1965, he was

living in San Francisco a couple blocks up Ashbury Street from its famed

intersection with Haight Street. He and Shirley were “into monogamy” and

neither drank or smoked or used dope, so they participated the fabled life of

Haight-Ashbury as observers. And Clay was an enthusiastic observer. During the

next two years, he witnessed first-hand the street theater that flourished in

the neighborhood, making The Haight a Mecca for flower children, particularly

in that storied summer of 1967.

The

Human Be-In staged in nearby Golden Gate Park on January 14 that year was, Clay

said, "an important event in my life. For the first time I realized how

many people were involved in what everyone felt was a movement toward a new

life style."

At

FSC, he brought the street into his classroom to stimulate student

discussions. They talked about hippies, psychedelic drugs, pop art, beat

poetry and rock music. Clay resisted the collegiate compulsion to segregate

knowledge by departments. "I was interested in all kinds of things that

overlapped the disciplines," he wrote, "—art, music, poetry,

happenings, drama, literature, history. I wanted to desegregate, to link up."

At

rural Sonoma, Clay's free-wheeling style was even more in tune with the student

body. "My Fresno acidheads saved up their acid and grass for weekend

parties," he noted, "but the heads in my Sonoma classes were stoned

all the time."

Submerged

for most of his adult life in a drug-using milieu, Clay himself wasn’t a

regular user. He occasionally smoked a joint, but he was, he said, "not

interested in experimenting with my consciousness. I was happy with my thought

processes the way they were. I could not understand why people would

deliberately fog themselves up, go out of their way to get into states I

considered negative or silly."

By

1969, the student revolt against the materialism of mainstream culture and the

war in Vietnam was in full swing. Clay was confronted in the classroom by

students who were mostly terribly uninterested in getting an education in a

world where that education seemed absurdly divorced from reality. Clay himself

felt alienated from professorial life. Instead of writing articles for

academic journals, he had started in 1968 reporting on the student revolution

for the Los Angeles Free Press (FREEP) and various underground

newspapers.

He

had found his niche. "I was born to be a daily reporter," he once

wrote. "I wasn't destined to survive in organized education. I was a

de-conditioner, not a conditioner. I wanted my students to think things out

for themselves, not to follow."

Henceforth,

Clay would make his way in the world on the street with a notebook and a

camera.

Much

of his reporting for undergrounds was done for little or no remuneration.

"At the time, I felt I was contributing to a mass movement for social

change," Clay said, "to the fall of a corrupt system and its

replacement by a more egalitarian and just one."

At

the same time, he could see a fallacy in radical revolution: "I used to

laugh at the SDS revolutionaries and their pipe dreams. My question was

always, Then what? So the government is overthrown and capitalism goes into

the trash can. Then what? How do people live in a smashed state? If you take

over, you have to be ready to run things. Someone has to know how to operate

the complex traffic system at the airport."

He

worked both sides of the Bay, roaming the neighborhoods in Berkeley and in

North Beach, prowling boutiques and novelty shops, delis and coffeehouses,

searching out news of the counterculture demi-monde and of other havens of

night music. He secured a monthly column in Coast magazine and

contributed regularly to the Berkeley Barb, the San Francisco Phoenix, and the magazines Adam, Knight, Oui, Hustler, and other hip

publications.

“I

made the best money writing about the sex scene,” he said. The real sex scene,

that is. Said he: “I was lousy at writing sex fiction, and I tried writing

pornography but couldn’t get past a couple of chapters. Porn is about people

who are nothing but their sexual activities. I’d write a few descriptive scenes

then realize I still had a hundred and fifty pages to go. I can’t even watch an

entire sex film. Everybody fucks until they’re blue in the face and then the

doorbell rings and two more couples come in and everything starts all over— Oy,

gimme a break.”

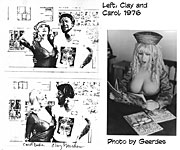

Prowling

North Beach, Clay worked up photo stories on nightclub personalities like Carol

Doda, the woman who introduced topless dancing to North Beach in 1964,

cavorting at the Condor. Doda also made silicone implants fashionable (and, in

her case, spectacular, as you can tell from Clay’s photo of her nearby).

Clay

knew Doda quite well. “She had trouble with her tits,” he told me: “She could

never lay on her side because the weight would fall and make her sore. I think

she regretted those boobs, but she never came right out and said so. Nice

person. Gay. She was having an affair with some married woman all the years she

was dancing onstage. Didn’t drink or smoke. She was into health foods. We used

to talk about macrobiotic diets and stuff like that. I still like a steak and

fries once in a while. ... Carol and my wife (Clay’s third, Clara Felix) would

get on. My Clara is a nutritionist by trade. Writes about it. Counsels. A

biochemist.” She produced a newsletter on healthy eating, and Clay drew cartoon

decorations for it.

"So

many scenes going on at once," he wrote about his life in those halcyon

days of yore. "I ran myself ragged. I took several rolls of film a day

and when I got back to the room late at night, I souped the negs and hung them up,

wrote my copy on the old portable Underwood that had gotten me through college,

then picked out the shots I liked and printed them. I always had everything

stamped and ready to mail the next morning."

CLAY'S STREET

ROVING acquired a different focus in late 1970 when he met underground

cartoonists Roger Brand, Justin Green, and Joel Beck. He started writing about

underground comix.

His

interest in cartooning was lifelong, albeit muted for a decade. As a kid, he

had copied Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Donald Duck and other funny animal characters

from comic books. "I got a great deal of satisfaction from cartooning,

but I seldom drew the realistic characters that required a study of

anatomy," he said.

As

a youth, Clay had achieved a dubious national distribution with his cartoons.

For a time during his stint at Western Electric, his job was nailing the tops

on packing cases that contained selectors and connectors for telephone

systems. "The work was slow, and I got into the habit of drawing cartoons

on the cases to make the guys I worked with laugh," he said. "I got

a kick out of the fact that Western Electric was distributing my gags all over

the country without knowing it."

The

emerging underground comix scene in San Francisco rekindled Clay's interest in

cartooning, and he began promoting comix in articles for FREEP and other

publications. When Ye Berkeley Comic Art Shoppe opened on Telegraph Avenue in

the fall of 1972, Clay quickly made friends of the owners, John Barrett, Bud

Plant, and Bob Beerbohm, and began clerking part time at the store. And when

they engineered the "world's first underground comix convention"

April 22-24, 1973 at U.C. in Berkeley, Clay worked in various minor roles and

helped with promotion, placing articles about the con in local periodicals and,

the week before the con, on the front page of San Francisco

Chronicle-Examiner’s Sunday Pink Section.

The

success of the con inspired Clay to other efforts in the realm of cartooning. He sold a three-day seminar on the

Contemporary American Comic Book, which he taught at the U.C. extension in San

Francisco in July 1974. The following January, he staged "Comics in

America Day" at U.C. in Berkeley; and he organized and financed

"Underground ’76" there, April 30-May 2, 1976.

"What

happened behind the scenes?" Clay asked, rhetorically. "Many

underground artists who had never met one another got together for the first

time. Books came together. Friendships. Paul Mavrides met Gilbert Shelton as

a result of one of my cons, and some years later, he was drawing the Freak

Brothers. Rand Holmes met the Bay Area artists and publishers for the first

time. The women cartoonists got together for the first time at the 1973 con.

The idea for a women's panel was mine, not a woman's. I suggested it to Trina

Robbins and got Shelby Sampson, Roberta Gregory, Joyce Farmer, and Lyn

Chevli—all of whom were on my mailing list and learned about the con from me—to

sit on the panel."

Another

of Clay's efforts inspired by the success of the 1973 Con was his newsletter, Comix

World. It is Comix World and the "Newave" of minicomics

that Clay fostered with the newsletter that earns him a place in the history

books.

The

newsletter grew out of a series of articles Clay did for FREEP; in

October 1973, he launched the first issue. And he kept it going for 22

years—sometimes weekly, occasionally monthly, most often every other week—a

running commentary on comics as they happened, history on the fly.

Subscriptions were $10 for 48 issues. He mailed the issues out once a month,

two to an envelope. By 1980, it was being mailed to every state in the Union

and fourteen countries, including Australia.

Ostensibly

about underground comix, the newsletter was actually about a good deal more

than that. It was Clay's forum. And it was an open forum—any subject that

caught his eye or raised his ire might be discussed in its pages. Even regular

newsstand comic books and comic strips. And movies. One issue was devoted

entirely to coverage of the Hooker's Ball. In short, the whole world of

cartooning and popular culture as viewed through the sometimes jaundiced vision

of Clay Geerdes.

Each

issue was a single 8.5x11-inch sheet, printed on both sides. The page layout

was strictly utilitarian: typewritten text meandered in a continuous,

unindented stream through islands of illustrations—panels clipped from comix,

covers of minis, and an occasional photograph. Every issue was larded with

plugs for comix—prices, titles, mailing addresses, short (occasionally longer)

reviews. Clay recruited friends and aspiring young cartooners to supply the

title logos for each issue, paying them with a specified number of free

successive editions. I contributed a few, always one of my favorite

barenekkidwimmin—as you can see from the ensuing gallery of Comix World souvenirs.

Clay liked naked ladies, too, and while sex per se was not the governing

topic at Comix World, the undraped feminine epidermis was often on

display. (I’m posting a sampling here to display generally the appearance of

the publication, but at the size these pages appear, the text is probably too

small to read; to make the pages readable, click on Page at the top of your

screen, then Zoom, then pick an enlargement size—say, 150%.)

Clay

saw the newsletter as a catalyst—"bringing cartoonists together, keeping

publishers and cartoonists abreast of what was happening in the underground

comix, hyping the comix and spreading them around in the other scenes of which

I was a part." Like Johnny Appleseed, Clay dropped copies of comix here

and there as he roamed his beats around the Bay, and he introduced cartoonists

to each other and told them of publishing opportunities he'd heard about.

In

his commentaries, Clay was opinionated and (like all of us) sometimes wrong,

but he was never vague, never wishy washy. And he was always energizing.

"My

seminal writing experience occurred during the zenith of Haight-Ashbury in the

mid-sixties," he wrote once in explanation of his approach. "The new

writing style of the time was subjective, not objective. A writer wrote about

the world as it moved him. He didn't stand in a corner paring his fingernails

like Joyce's ideal writer; rather, he went and sat on the floor in the back

room of the Psychedelic Shop and rapped with the people who were flowing into

The Haight every day in search of free acid and a liberated social and sexual

lifestyle. He stood as I often did on the corner of Haight and Masonic and

enjoyed the various conversational styles of people like Pigpen (electric

pianist and organist for the Grateful Dead —he died with he was 27), Chocolate

George (Hell's Angel, also dead), and Janis (also dead). It was my style in

those days to put it all in, all the images and the conversational fragments,

the contrasts between the cowboys and the flower children and the hippies and

the radicals."

His

writing reminded me of Henry Miller's straight-ahead style; and I liked them

both.

"There

are a lot of opinionated people in this world, and I am one of them," he

wrote. "I pay for the privilege. It's my newsletter and my money. Comix

World exists because I got very little satisfaction out of writing for

other people's magazines and papers." He enjoyed getting feedback, and he

didn't get any of it from other publications he contributed to. Not enough

anyway. But he did with his newsletter.

Ever

outspoken and never pulling his punches, Clay could be devastatingly brief in

rendering a verdict. About a clutch of 1982 movies, Clay offered the

following: "Someone asked me if I saw Blade Runner.

Unfortunately. A sordid piece of decadence filled with second-hand ideas and depressing

images. Brutal and misogynistic. A celebration of ultra-violence which ends

with the State's butcher riding off into the sunset with an android. A

footnote to Clockwork Orange and Escape from New York. Why

doesn't someone tell the assholes that make garbage like this that we don't

want to see a hero who is really a villain and we don't want to see women

brutally killed and we don't want to watch Harrison Ford get his fingers

broken. Blade Runner is for you people who have the no-future-I-ain't-gonna-make-it-to-thirty-so-why-not-just-fuck-kill-and-die-early

syndrome. The Road Warrior is in the same bag. A sleazy rip-off of

Spain's ideas in Subvert 3. If you judge the value of a movie by the

number of decapitations, then Conan is right up your grommet. Racist

sleaze and gore. The only film from this summer crop that retains any human

values is Star Trek II. It's hippies and straights in space, the

villain is too weak and Kirk too smart, but it has its moments."

Acerbic

albeit witty scorn oozed from his opinionated prose: “Berkeley is turning into

a mall,” he wrote in 1992. “The yuppies have won. Some morning, I will wake up

and find out they have built a Toys R Us around me. I’ll have to dig my way out

of a pile of naked Barbie dolls and GI Joes before I can have my morning tea.”

He

reported occasionally on conversations he'd had with such stellar figures as

Harvey Kurtzman (a notorious hold-out who Clay had successfully seduced into

appearing at "Underground ’76" and who had supplied a logo for Comix

World —which image was later emblazoned on T-shirts that Clay wore):

"Remember those turgid subliminal erotic dramas in Fox and Fiction House

mags? Sheena and Bob? Or GI Jane? Best of all, Skygirl. I always loved the

way Skygirl (who was a waitress in a cafe at an airfield) managed to get her

clothes nearly blown off on every accidental flight she took. She was great.

Kurtzman and I were talking about those formulas a couple years ago, and he

admitted swiping a lot from Sally the Sleuth and from Skygirl when he and Elder

got into Annie Fanny in 1962."

|

|

About

sexy female models at comicons: "Sybil Danning, a model who appeared on

the cover of last December's Oui, was signing copies of the mag and

posters at a table. For $2, people could pose with her and get the polaroid

shot signed. Now, are the folks back home going to believe that you could score someone like Sybil at a comic con? Sure, why not? Blondes in half-unzipped

black leather jumpsuits fall all over me everywhere I go. California is like

that."

About

Disney's famed Snow White: "Am I the only person who sees that

Snow White betrayed the guys who loved her and took care of her by running off

with a rich flake on a white horse? That she was saved by a group of working

men only to run off with an imperialist?"

Clay

sometimes went to extremes when debunking what he believed were popular

misconceptions. “I always liked the story Walt Disney’s daughter Diane

told about her dad creating Mickey Mouse in his garage when a mouse jumped up

on his drawing board one day. Sounds good, but how could this be when Mickey

was a 1928 modification of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit by Ub Iwerks? [Oswald had

been appropriated by Disney’s distributor; Mickey was created to replace the

stolen character.] Do you know that Johnny Gruelle used ‘Mickey’ and

‘Minnie Mouse’ in a short story in Good Housekeeping in 1919? Yep, even

the names belonged to someone else. As for the idea of a mouse couple, check

out the enclosed stat from Cartoons magazine in 1920.  Walt and Ub were both

aware of this mag I am sure, and they borrowed a lot from it.” Walt and Ub were both

aware of this mag I am sure, and they borrowed a lot from it.”

All

of which could very well be true. But in 1919, Disney was 18 years old, just

returned from driving an ambulance in France during World War I, and trying to

get started as a cartoonist in Kansas City. I doubt he spent much time reading Good

Housekeeping. And Lang Campbell, whose mouse couple Clay hauls up to

bear witness, wasn’t the only cartoonist anthropomorphizing mice and other

animals for his cartoons in those days, so the cartoon on display here is

scarcely conclusive evidence that Disney and Irwerks borrowed husband and wife mice

from others. In the Disney legend about the creation of Mickey, Disney

initially named the rodent Mortimer, but his wife persuaded him that Mickey was

a better name. And once you’ve created a male mouse as a leading character, the

next logical step is to give the mouse a mate, or at least a paramour. Naming

her “Minnie” perpetuates the euphony in m-words.

In

short, the origins of Mickey and Minnie can be explained without resorting to

insinuations about theft and other high-handed chicaneries. But Clay enjoyed

exploding whatever he regarded as misapprehended mythologies. And he was often

right. Here, however, I think he’d wandered off the lot a little. Disney and

Irwerks both read Cartoons magazine in 1920 while working together in

Kansas City and kept the idea of a mouse couple in the backs of their minds for

more than eight years so they could conjure up a girlfriend for Mickey? That’s

a more remarkable feat of creation than simply inventing the mouse couple out

of whole cloth. Minnie appeared with Mickey in the first of his animated

cartoons in 1928, but she apparently wasn’t named until the next year in

“Mickey’s Follies” (June 1929). (Cartoons, incidentally, ceased

publication with its December 1921 issue.)

It

was exactly this sort of discussion that animated the correspondence between me

and Clay for nearly 20 years.

THROUGH IT

ALL, CLAY'S HIGH OPINION of cartooning shone like a beacon, particularly

underground cartoonists: "All of the underground comix made it a point to

attack the hypocrisy and moral prudery of the Establishment," he wrote,

"to gross out the straights, the business cult, the nine-to-fivers, the

hapless adults who had to work to make the money to pay for the excesses of

their runaway kids who were hanging out smoking pot in Haight Ashbury or

Tompkins Park."

Another

time: "The comic artist of our time is still the ultimate social rebel,

the one who debunks and defuses the ad-hype and brainwash and outrages the

uptight by drawing what ‘shouldn't be drawn.' He not only thinks what is

taboo; he draws it. So does she."

Clay

could work up a fine rage about the way cartoonists were treated in the

so-called "art world": "I started commercial art in college and

got turned off totally by the assholes teaching in the department—you know,

those prissy dabblers who always have something negative to say if you draw a

cartoon. A lot of my friends have made the rounds of the galleries and gotten

shit on by those fine-art assholes. It's a totally corrupt scene out here from

Sutter Street to Laguna Beach (where the big art show is every summer). If you

do comics, they look at you like a pigeon just shat on their ascot. Most

cartoonists I know can draw so much better than those scenery people it isn't

funny."

In

the late 1970s, Clay began promoting minicomics. This was the

"Newave," Clay's "Comix Wave.” These were mostly self-published

8-page booklets. You published yourself a minicomic by photocopying your

comics on both sides of an 8.5x11-inch sheet, then folding it twice and

trimming off the top to create 8 separate pages, each measuring roughly 4x5

inches. In the emerging age of photocopying, everyone could be a publisher at

ten cents a copy or less.

Clay's

contribution to the movement was to act as cheerleader nonpareil and publisher for

new cartoonists who may not have access to the technology. He urged neophyte

cartoonists to send him cartoons—individual gag panels or multipanel comic

strips, drawn 5x7 inches, which he then cobbled together under anthology titles

like Babyfat, Fried Brains, Bad Girl Art and so on, laying out the

individual 5x7-inch contributions on his 8-page format and reducing them in the

photocopier as he punched out a press run. He sold them for 50 cents and a

first-class stamp. And he gave a lot of them away, too; good publicity for the

cartoonists.

Clay

explained the origin of the title of one of his anthology booklets: “The idea

for Babyfat came to me one night when David Nadel and I were sitting at

the counter at Denny’s in Emerykville, California. We used to go there to eat

after David’s dance club, Ashkenaz, closed. [Clay worked regularly at “the

Naz.”] As we discussed the events of the evening, I doodled cartoons on napkins

and one of those little sketches became Babyfat. To me, the title

referred to all the humorous residue of our sessions. Babyfat was to the

social order what it was to the body—the excess. ... Because I doodled a fat

girl in a T-shirt for the first cover, many cartoonists that followed got the

idea that shew as Babyfat, that the chubby girl was the symbol, which is why

there are so many chubby girl covers.” Not mine, by the way—as you doubtless

perceived when perusing the Comix World gallery a few winds of the

scroll ago.

Cartoonists

who contributed mincomics received publicity in Comix World (which Clay

formally re-titled Comix Wave after a while) and copies of the

minicomic. Clay also advertised the minicomics produced by others in the

newsletter.

No

one got rich by any means. Clay hoped only to sell enough of one title to pay

for the printing of the next one. "Perpetual art," he called it.

Like

any experienced cartoonist, Clay knew that the best way for his minicomic

cartoonists to learn their craft was by seeing their work in print; and they

learned something about the commercial side of publishing comics by dealing

with him.

"I

operated the miniseries the same way I had run my college classes," he

wrote. "No one was rejected. Ideas were accepted and put out there for

others to deal with. The kid who did a minicomic just for the hell of it would

drop out of the game in his own time. Why should I discourage him?"

He

was the ideal missionary editor-publisher. As comics critic Dale Luciano once

wrote, "Geerdes extends to the young cartoonists who appear in his

publications an attitude of unconditional positive regard."

Clay

published virtually everything he was sent. (But not pornography; sexual

stuff, yes—but only if it was funny.)

"The

whole idea," he told Luciano," is to publish someone who has decided

he does something that is ready to publish. That is not for me to decide, but

for the artist or cartoonist. If it's total crapola, others will tell him, and

he will learn from the experience. If I just send it back with a nasty note,

he learns nothing, and his cartooning impulse is repressed. I want to help

people who contact me to gain confidence in themselves and their ability to

venture out into the public world."

In

minicomics, Clay the maverick idealist found another of his niches. Minicomics

represented the ultimate in freedom of expression, in unfettered creative

enterprise.

"Complete

freedom of expression is costly," Clay wrote, "because the mainstream

rejects it and holds out for a sanitized product. Depending upon the reader,

the newaves are sexist, racist, heterosexist, homophobic, leftist, right wing

fascist, agist, and too many other ists, isms, and ologies to list here. I

still feel that art should be free from any restraint. I may cringe at some of

the fantasies I see on MTV or in the pages of contemporary comic books, but I

would rather see it all out there than live in a society where it is repressed

as in Bradbury's Farenheit 415."

In

pursuit of this passion, Clay published over 40 digest-sized magazines, a Newave

Guide, and 300-400 minis. Said Luciano: "Geerdes clearly deserves

credit for playing the most instrumental role in launching and ballyhooing the

wave of self-published comix which began in the 1970s."

AS HE LURKED

THE SHADOWY NIGHTOWL STREETS of North Beach and Berkeley, Clay developed a keen

sense of history. Among other things, his appreciation for history led him to

donate a complete collection of Comix World/Wave to the University of

Iowa and to ask Gary Usher to index the collection. The run of the newsletter

provides a week-by-week history of the most prolific period in publishing

underground comix.

At

the time he started the newsletter, Clay also began a journal in which he kept

track of new comix. He regularly visited the Print Mint warehouse in Berkeley

and Last Gasp in San Francisco, jotting down the titles of comix as they

surfaced. And he talked regularly (and sometimes at length) with underground

cartoonists and publishers, who filled him in on the earlier developments in

the medium. As a result of the knowledge he accumulated, Clay could wax

eloquently sarcastic about so-called histories of comics and comix.

"Comic

book scholarship is in its infancy and I can safely say that most of the books

extant are seriously inaccurate, many distorting history, others ignoring it, most

unaware of it. While anyone would accept the absurdity of a monograph about

William Faulkner with references only to secondary sources, it is the rule

rather than the exception to see articles about comic books which contain no

primary references at all! The damage already done is serious and will not be

corrected easily—if ever."

His

favorite example of misapprehended history concerned the dating of Zap Comix No.1. Don Donahue, the publisher of record, asserted in the Introduction to The

Apex Treasury of Underground Comics that Zap Comics No.1 was

published in 1967. But that, Clay demonstrated, was clearly wrong. "The

cover and guts for the comic were printed by Charles Plymell, a poet and

publisher of Last Times, on February 24, 1968, and the books were folded

and stapled on the floor of Crumb's apartment in Haight-Ashbury. . . . The

first Zap comic book appeared in the Haight-Ashbury on the street on

February 25, 1968."

Donahue

simply forgot, Clay said. And he and others have been mislead by the date on

the artwork. Crumb drew the material that appeared in the first issue of Zap in the fall of 1967. And he wrote "1967" on some of the art, thereby

leading Donahue (who should have had a better memory of the occasion because he

helped Crumb and some friends fold and staple that first issue) and everyone

else astray. But real historians, Clay maintained, would have got the facts

right. They would have consulted records rather than relying on tricky

memories alone.

But

history deserved scrutiny and interpretation. Clay reviewed my first book, The

Art of the Funnies (1994) in Comix Wave No.153, and recommended it

“without reservation,” adding to its lore the following:

“Harvey

says Bud Fisher’s Mutt was short for Muttonhead, and perhaps that is

true, but I suggest an alternative. Fisher and his peers had to take Latin to

graduate from high school, and I suspect he recalled a bit of Latin when he

named his character. Mutt comes from the Latin mutus, which means

dumb, but it could also come from mutonis, the word for penis,

hence Mutt is a dumb dick! Turn Mutt’s head upside down, and his nose becomes

an erect penis; his moustache, pubic hair. Sidney Smith picked this up

for his chinless Andy Gump, and it was later copied by Jay Lynch for his

character, Nard. This shift from bulbnosed characters to phallic noses was not

accidental.

“Augustus

Mutt has an elevated classical first name, yet he is a lowlife character whose

entire life is dedicated to playing the horses. Augustus was Caesar’s title and

meant consecrated, sacred, or majestic. To pin this on Mutt was an in-joke. A

man like Fisher with aspirations to higher education (he started college) would

have enjoyed juxtaposing the highest and the lowest, knowing that his readers

would get the joke unconsciously whether they could understand it

intellectually or not. One of the reasons Robert Crumb’s art made people

laugh so hysterically in the late sixties was his technique of making overt

what had always been covert in comic strips. Mutt and Gump and, yes, even

Popeye, were all dicknoses, but Crumb drew a strip about a character who had a

real dick for a nose. Such flagrant phallicism was an outrage to repressed

or ‘normal’

people, hence very popular with a younger generation in rebellion against parental

values.”

It

might be a stretch to accept all of Clay’s elaboration on the alternative

meaning of “mutt,” but his contention that Mutt’s nose is an erect penis and

his moustache, public hair is impossible to ignore.

Clay's

historian’s antenna were always up—and not always just about comics. Once I

wrote him about a book I'd read by the ghost writer who did the earliest Hardy

Boys books. Clay came back with fire in his prose: "Don't know what book

you read, but the guy is a liar if he said he wrote the first ten Hardy Boys

books. Edward Stratemeyer always wrote the first three himself; all of his

series. Every one."

Maybe

not. I didn’t question Clay’s assertion at the time (although it is the sort of

Geerdeschism that I sometimes did question, precipitating a politely

argumentative exchange of letters) because I didn’t know much about Stratemeyer

then. Later, however, I learned that this founder of the “fiction factory” of

juvenile literature wrote many of his books (beginning with the Rover Boys

through Tom Swift and the Bobbsey Twins and ending with Nancy Drew), but

because he didn’t have time to write them all, he devised an unusual

assembly-line method of producing books: his customary procedure was to supply

a stable of writers with plot outlines, then he edited the text a writer

generated from outline.

Canadian

journalist Leslie McFarlane, the Hardy Boys writer Clay assaults, went on to

become a writer for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and then a director

on the National Film Board. Before writing the first ten Hardy Boys books, he

had written Dave Fearless books for Stratemeyer, so he was not an unknown

talent when Stratemeyer proposed that McFarlane launch the new boy detective

series in 1927.

I

consulted four books about the “Stratemeyer syndicate” (as its inventor called

it), but none of them claimed Stratemeyer “always” wrote the first three

volumes in any new series. He wrote the first three Nancy Drew books, but it’s

not clear that he did the same for every series. The first three books in a new

series were always published at the same time: they were called “breeders,” and

their simultaneous publication was intended to establish interest in the series

by giving readers an immediate opportunity to purchase more books in the same

series. Perhaps this practice lodged “the first three” in Clay’s mind.

Stratemeyer, although he loved to write, was a better businessman than author.

He devised the “pearl necklace” maneuver as a way of

promoting

book sales. All the books in a series were strung together like pearls on a

necklace: on the second page in every book, the title of the book recording the

character’s previous adventure was mentioned; on the last page, the title of

the next book in the series.

But

I didn’t know enough about Stratemeyer when Clay burst out about the author of

the Hardy Boys: I couldn’t argue with him.

Clay

was prickly and self-reliant. "You see," he told me once, "I

can't get along with people. You have a way of fitting in. I have none of

that mellowness in my make-up. If someone fucks with me, I never deal with

them again. It's cost me, I know, because writing for other people is always

compromise, but that's how I've lived my life. I never compromised with anyone

when I was teaching either. I saw the brownosers hang in and get their tenure

and spend their lives babysitting those teenaged assholes in the valley, and

all I can say from here is that they got what they deserved and thank God I was

refused tenure and had to do something more interesting with my life."

Clay

folded Comix World/Wave in mid-1995. After 22 years putting it out, he

found he'd lost interest. The new generation of comics didn't appeal to him,

he said. Typically, he wouldn't compromise with his feelings, so he could no

longer write about the medium.

There

was more to it than that, I think. Bob Rita, a co-founder of the Print Mint,

died of a heart attack in February 1995. It was as if an era had passed. And,

of course, so it had.

When

he wrote me, Clay sometimes mentioned his sense of malaise about comics.

Somehow he related his feelings to the untimely deaths of so many of the

underground cartoonists, people he'd known and whose work he'd admired. He

catalogued the death knell: "Cheech Wizard Vaughn Bode died in 1975 of

strangulation caused by an auto-erotic device he was using. Willy Murphy (Flammed-out

Funnies) died of pneumonia, March 2, 1976. Dealer McDope David Sheridan

died of cancer, March 28, 1982. He was a heavy smoker of nicotine and

marijuana. Rory Bogeyman Hayes died of an overdose of pills in 1983, possibly

suicide. Greg Irons went to Thailand to study tatoo art and was run down by a

bus in 1984. Roger Brand died of kidney failure brought on by alcoholism,

November 30, 1985. Dori Seda died of pneumonia shortly after a traffic

accident, February 2, 1988."

But

the feeling of malaise had other origins, I think. Clay wasn't feeling well

himself. In the summer of 1995, he began to feel weak and tired much of the

time. He thought it was simply a symptom of age. Unbeknownst to him, it was

cancer.

By

early 1996, he felt pain in the abdomen. That summer, he detected a lump. In

October, he finally went in to get checked. It was colon cancer. The tumor

and a foot of intestine were removed, and Clay went home to recover.

class=WordSection2>

But

the cancer had metastasized to his liver, and that condition required

treatment. Clay, never conventional about anything I ever knew about, wasn't

going to be conventional about his cancer treatment either.

Earlier

in the year, he'd commented to me about Gil Kane's ordeal with cancer:

"The bastards almost killed Kane," he wrote. "What the

medico-cancer business does for people is to offer nothing but surgery and

chemo which make the last few years of life painful and unbearable. I've known

too many people to have been killed by this system. If I get the disease, I am

going to use alternatives to fight it and die in my own way."

And

that's what he did.

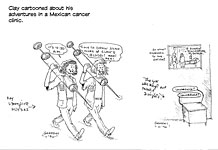

In

November 1996, Clay checked in to a clinic in Mexico and submitted himself to an

alternative treatment that involved ingesting quantities of vitamin supplements

and having his teeth removed because of the metal fillings that promoted the

growth of small tumors in his liver. He wrote about aspects of his experience

later with his usual flair for both narrative detail and the human comedy:

"I

had two [teeth extraction] sessions. Both scenes of high comedy. Peter

Sellers would have loved it. I am flat on my back in the chair and the dentist

is shooting me up with enough novocaine to stone an elephant; meanwhile, his

gorgeous dark-haired nurse is watching the show while both listen to pop

Mexican songs on the sound system. As my molars pop out and onto the tray,

they are discussing the singers. It's all in Spanish, but I have spoken that

language since I was a boy working at the Cornhusker Hotel in Lincoln, so I

understand nearly everything they are saying and realize the absurdity of it

all. I am losing my teeth while these folks are chatting about pop music and

fashion. She's defending the pop music preferred by her generation while he,

in his early forties, admits to liking some of it but finds too many of the

song lyrics dirty. Through all of this, I am aware of a flirtatious

undercurrent between them."

Miraculously,

as soon as the last of the metal-filled teeth were removed, Clay reported that

the pain in his liver subsided—disappeared—immediately. He returned to

Berkeley on Thursday, December 19.

There,

he encountered tragedy.

The

night that he and Clara returned, David Nadel—Clay’s friend, kindred soul and

part-time employer—was shot and killed by an Ashkenaz patron whom Nadel had

ejected from the dance club for being drunk. At the hospital, Nadel was kept on

life support until Saturday because he had donated his organs and they were

being removed for transplant. His killer, later identified as Juan Rivera

Perez, a Mexican national who was in the U.S. without papers, was never caught;

presumably, he returned to Mexico to avoid capture.

Clay

reacted in the way writers everywhere react to tragedies that touch them: he

wrote a long essay about his friend. Nadel had started Ashkenaz as a “folk

dance collective” in March 1973 “to establish a venue which would feature a

different kind of folk or ethnic dancing each evening, culminating with an

international night on Saturdays.”

“David

loved to dance,” Clay continued. “He was probably happiest when he was out on

the floor dancing with his friends, doing the complex figures of a Balkan or

Macedonian dance.” But he was interested in all kinds of music, and cajun had

become the staple at the Naz by the mid-1990s. Nadel spent the daylight hours

of every week on the telephone, cajoling band leaders to bring their bands to his

club and putting together his monthly calendar of events.

Clay

and Nadel shared most political opinions, and Nadel expressed his in the

editorials he wrote in the calendar. In his eulogy, Clay quoted from the last

editorial Nadel wrote:

“Corporate

capitalism many times has laid itself open for all the world to see its ugly

basic tenets—the exploitation of people and the earth’s resources so as to

squeeze every drop of profit out of life. ... A clean environment and

capitalist exploitation of the earth is a contradiction! Let us outlaw greed,

spread the wealth around, slow down ... for fear we irreparably foul our nest

to where cockroaches inherit the earth.”

In

the same defiant spirit, Nadel flew a banner atop his building, the last one

proclaimed: “Tax the Rich ’til There Ain’t No More Rich.”

“The

Ashkenaz as we all knew it ended on December 19, 1996,” Clay wrote. “The club

may continue in some form, but it will never be what it was because there is no

one who could replace its creator, David Terrence Nadel—friend, brother.”

For

awhile after his return from the Mexican clinic, Clay reported gaining in

strength and maintaining his weight, both encouraging signs. He felt good

about what he'd done and had no regrets whatsoever. But he was scarcely back

to normal, and in May, he wrote that he was sleeping most of the time. I

didn't hear from him again. He died at 1:30 a.m. on July 8, 1997. It was a

Tuesday. He was at home in Berkeley with Clara Felix. He died quietly:

"He just stopped breathing," Clara told me. He wasn't afraid; he

wasn't uneasy; he wasn't in pain particularly. He'd had his 63rd birthday in

May, surrounded by friends and family.

He'd

sent me a 270-page book of his essays and short stories, mostly

autobiographical; from that and his letters and issues of Comix World/Wave,

I constructed this biographical account. On the frontispiece of his book is a

photograph of Clay, sitting at a piano and looking over his shoulder at me, a

grin on his face and a twinkle in his eye.

In

his last years, he'd returned to his piano with a genuine passion. "What

I like is playing my piano," he wrote me. "I spend a couple of hours

a day working out. Mostly ragtime music. I am a fan of Joplin and play all

his stuff quite well these days. I'm still not letter perfect, but I

struggle. I always regret not working on my scales more as a kid, but my dad

couldn't handle it. He was bad enough when I just went over my lessons."

Looking

at him there in that photograph, I can almost hear his voice—talking about

comix, mostly, extolling them: "I have to laugh again as I remember

seeing people standing in the comic store on Telegraph, laughing their asses

off over Crumb's Big Ass Comics. I could hear them saying, 'This is

really disgusting!' More laughter, then, 'This is really gross!' followed by

more laughter. That's the pleasure and the paradox of comix."

Fitnoot. The foregoing is

an expanded version of my article published after Clay’s death in the Comics

Journal. While editing for this posting, I rummaged around for sample

copies of Clay’s Comix World. I knew I’d saved some, but where? Found

’em in a box—with a bonus: a file folder of copies of the letters we’d

exchanged. I thumbed through the heap, pausing to read one here and there. The

temptation grew to read them all. I was impressed anew with Clay’s eclectic

erudition, often across a wide range of obscure topics—like the Mutt paragraphs

above—and his lively, energetic conversational prose. Action verbs, a generous

seasoning of profanity, and strong opinions. And wonderful out-of-the-box

insights. Every once in a while, reading in this cache something Clay had

written, I’d say to myself, “Well, I wonder if he’s heard about —.” Some new

wisp of related information. I’d think, for just a moment, that I should tell

him about this new development to see what he thought about it. And then, I

remembered. I couldn’t tell him: he wasn’t there anymore.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |