BUCK BROWN

AND HIS INSATIABLE GRANDMOTHER

One of

Playboy’s Original Line-up of Cartooners in Color

Buck Brown, one of Playboy’s contract cartoonists for almost 45 years, died last

summer on Monday, July 2, of complications after suffering a stroke on June 23.

He was 71. Respectful obituaries appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, his hometown newspaper, and elsewhere, including

the International Herald Tribune, which suggested his status in the culture as well as at the magazine. Playboy, which goes to bed months before

its publication date, wasn’t able to recognize Brown’s absence until its October

issue. Brown

was an important cartoonist because he was a good cartoonist. He drew funny,

sophisticated cartoons. He was in full command of his medium, whether in black

and white or in color. And he invented a memorable character, the laughably

lascivious Granny, who, like all uniquely original creations, outlives her

creator. When Reese’s article appeared, Brown was still

alive. He was in the twilight of a long career and a little frustrated, puzzled

by the fading light. “He had outlasted the glory days of the magazine,” Reese

wrote, “in which his contributions were an important ingredient in the

successful Playboy formula. As

creator of the iconic Granny cartoons—panels that featured a sexually

insatiable, long-nosed elderly sprite—Brown kept a couple of generations of Playboy readers laughing out loud. ...

While Granny still makes sporadic appearances in the magazine, she has, by and

large, been retired.” And so has Brown, Reese said, and not altogether

voluntarily. “Slowed by a heart attack and complications from diabetes and

cataracts, he continues to paint and draw. He loves his work, but is no longer

earning a living at it, which upsets him. He’s used to making money. ... This

presents a challenge,” Reese continued, “partly because of his health but also

because of his industry. ... Brown realizes that Playboy is currently chasing a younger audience and that his brand

of funny isn’t an easy sell to the ‘

And

so, maybe, is Playboy. “Though Playboy still boasts a circulation of

about 3 million and Hef, at 80, still cavorts in his pajamas with women young

enough to be his great-granddaughters, the magazine has lots its edge,” Reese

went on. “As Playboy started its

decline, Brown’s career also lost steam.” In his best years, his cartoons

appeared not only in Playboy but in Ebony, Jet, Dollars and Sense, Esquire, The

New Yorker, and the like, plus the Chicago Sun-Times and an occasional book. But over the years, Reese

observed, “magazines were using fewer and fewer illustrations. Consolidation in

book publishing meant fewer opportunities for artists. Playboy became Brown’s lone source of regular employment, and even

it was becoming indifferent. Granny, it seems, had worn out her welcome.”

He

wasn’t “blistering with rage” about his unaccustomed and unwelcomed retirement,

Reese noted; “he’s stewing with solemn, old-man disgust. Still, Brown is proud

of his run at Playboy. ‘Forty-five

years on any corner is good,’ he reasons.”

Brown

wasn’t angry, but Reese was. He felt the magazine was slighting one of its

mainstays, ignoring Brown in its 50th anniversary commemorations and

not publishing his cartoons. Later, after the publication of Who-Ville, he learned why. “In the end,”

he wrote me, “I found out from Playboy that the reason Buck’s assignments began to diminish was because his line was

‘off’ in the time following his cataract surgery. He didn’t notice it, but the

magazine did.”

Before

sending me the article for posting here, Reese revised it slightly, leaving out

what he called “the animosity.” I didn’t see as much animosity in it as he did.

And I thought the material that I’ve culled from the original piece in the

foregoing paragraphs completed the portrait of Buck Brown. His vitality may

have been fading, but he remained a proud and accomplished cartoonist with a degree

in fine arts and a passion, still, for painting. In his acceptance of his fate

with Playboy, Brown shows a gentle

forbearance that maintains a great and enviable dignity, as a man and as a

cartoonist.

Now,

here’s Reese’s article; after which, we’ll have a Granny Gallery and then a few

words about Ronnie Reese. Stay ’tooned.

Keeping Granny Alive

Robert “Buck” Brown is sitting in the living room of

his comfortable south suburban Chicago home, poring over photos of old

acquaintances — centerfold models in Playboy magazine. Most of the women in the decades-old magazines no longer resemble the

images preserved on these pages. Some of them are no longer alive.

“I

met her, and she’s dead. And I met her, and she’s dead,” Brown reminisces, as

he flips through the glossy magazines, a tinge of melancholy coloring his

voice.

At

70, Brown, who for more than 40 years was a cartoonist at Playboy, has outlasted many of the Playmates he met over the years,

a time in which his contributions were an important ingredient in the

successful Playboy formula. As

originator of the iconic Granny cartoons — panels that featured a sexually

insatiable, long-nosed elderly sprite — he kept generations of readers laughing

out loud. Brown has drawn children, cops, pimps, prostitutes, John F. Kennedy

and Truman Capote — both JFK and Capote in the same panel — but Granny is the

greatest part of his legacy, and perhaps more well-known than her creator.

Longtime Playboy Cartoon Editor

Michelle Urry, who worked with Brown from the early 1970s until her death in

October of 2006, once wrote about his seminal figure as a “little old lady

complete with saggy appendages and a bun that was absolutely nothing like him.

People constantly commented on her as a character that provided comic relief for

them.”

“In

order to succeed as a comedian or cartoonist or what have you,” says Brown, who

is long-limbed and ingratiating, and bears a grizzled resemblance to “60

Minutes” correspondent Ed Bradley, “you have to have an audience, and you have

to be able to appeal to that audience. If they don’t look at it and laugh, then

what are you drawing for?”

It

was such an understanding of the nature of his craft that provided motivation

for the impish innocence that Brown and cartooning peers such as Eldon Dedini, Doug Sneyd and Erich Sokol perfected for five decades

at Playboy. Their illustrations have

always been an integral part of the magazine, something which evolved out of

the cartoon traditions of Esquire and The New Yorker.

It’s

an old cliché to hear people say, “I only read Playboy for the articles,” but there are some that do. Others find

the pictorials more to their libidinous satisfaction. Yet for a select few, the

single-panel comics are the appeal. A talented cartoonist contributes more to a

magazine’s overall tone and voice than is typically realized.

At Playboy, Brown has always known his

role, and he also knows there is one area in which he has to figuratively draw

the line. His entire life has been dictated by what he does for a living, but,

as he is often quick to point out, “I’m still just a regular dude. People see

me as a Playboy cartoonist,” Brown

explains, “so they presume I’m some big freak or something, but that’s only in

terms of coming up with the ideas. And I refuse to pose in the nude.”

*****

Buck Brown has been a freelance cartoonist for his

entire career. He hasn’t had a “real” job since the 1960s, when he drove a bus

for the Chicago Transit Authority. “When I met him early on in his career,”

Urry wrote to The Star newspaper of

When

he introduced her to Playboy readers

in 1966, the magazine was in its 13th year of existence. The repression,

conventionality and conformism of the ’50s was gone, yet it was still an

anomaly to see a hunched, white-haired old lady in constant heat, lusting after

any man who would have her, as well as those who clearly wouldn’t. Granny loved

to ball, and was a perfect fit for the Sexual Revolution.

“The

initial popularity was because of the outlandishness of this wizened old woman,

with her sagging breasts, being so sexually voracious and eager,” says R.C.

Harvey, an author and cartooning scholar. “That fit into the general Playboy philosophy, which is that women

enjoy sex as much as men do. It was a way of comedically emphasizing that

aspect of it.”

“I

thought the Granny character had a real sweetness to her,” says Gahan Wilson, a fellow Illinoisan and

longtime Playboy illustrator.

Granny

was a star. And even though few casual observers knew his name, Brown was a

star by extension.

“My

mother was such a fan,” says Kerig Pope, who served as managing art director at Playboy for 36 years and worked

closely with Brown on a handful of illustrations and other pieces. “I told him

that and he did a Granny cartoon just for her. She absolutely loved it.”

Art

enthusiasts knew Buck Brown’s name and his technique, though maybe not his

face. Once, while entering a cab in

“What

are you, an artist?” the driver asked.

“Not

really. I’m a cartoonist.”

“You

mean like Buck Brown?”

Brown

could hardly contain the excitement of being “recognized.” “I knew then,” he

recalls, “how Jimmy Stewart must have felt in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’”

And

no group appreciated Brown’s work more than his contemporaries. “Buck’s got

that ability to put across what he’s doing and what his intentions are,” says LeRoy Neiman, one of the most popular

American painters of the 20th century and a Playboy contributor for more than 50 years. “That’s a very special thing. He knows his

craft, he knows his art, and he knows how to get his point across. He’s a

special one.”

What

makes Brown’s accomplishments even more special is that he is an

African-American cartoonist who made his mark with work that was not primarily

race-based. Yet he was still able to address racial issues, “in a way that no

one else was doing,” according to Urry, “[with] gentle but sophisticated takes

about the protest movement and civil rights issues of our time.”

“I

could always handle civil rights,” says Brown. “I am civil rights, but it

probably helped me because Playboy couldn’t see my face. It was a long time before anyone even knew I was black.”

“The

idea that Buck was a black man, most people didn’t realize that,” Pope

explains. “I think that was the greatest thing in his favor, that they didn’t

put that together. Nobody published it and made it a big issue. It was just

that people liked the cartoons and thought they were funny, but it was

definitely an achievement.”

*****

Brown was born on

He

noticed a transfer student drawing cartoons one day in elementary school, and

realized that, at the same age, he could also become an artist. Brown soon took

up cartooning as a personal pastime, eventually standing out among his

classmates and establishing himself as the only member of his immediate family

with any discernible creative ability. He was in high school when he saw Playboy for the first time in a local

bookstore.

Launched

in 1953 by Hugh Hefner, a former promotional copywriter for Esquire, Playboy immediately became the

model for post-World War II perceptions of American sexuality. With its

tasteful nude pictures of the quintessential girls next door, and high-brow

fiction and literary journalism, the magazine offered a guide to an imaginary

lifestyle that few men could actually afford to live. Still, its appeal was

undeniable.

“I

would go in [the bookstore] and look at the girlie books and stuff,” Brown

recalls, “and this one stood out so distinctly. I said, ‘Wow ... I’m going to

have to start stealing this!’”

After

graduating from high school, unsure about whether he could meet the rigors of

college course work, he entered the Air Force and began working as a hydraulic

mechanic. While in the service, Brown drafted caricatures of some of the

lower-ranking members of his company, like the squad drunk waking up with a

hangover and putting his shirt on his legs and his pants on his arms. “I was

gaining confidence and really getting it then,” he recalls. “I was starting to

understand the power of the pen.”

One

afternoon, he got a large sheet of butcher paper and drew a caricature of

everyone in the squadron in individual states of absurdity. “All the guys came

in, got the drawing and put it up on the bulletin board,” says Brown. “I didn’t

want it up there, because I knew the chance I was taking drawing white folks

back then. You have to realize that this is the mid-fifties. Martin Luther King

hadn’t marched anywhere yet. And sure enough, a couple of days later, someone

came in and said, ‘Brown, the CO [commanding officer] wants to see you.’”

“Drawing

white folks,” was the young artist’s initial worry, but ironically, his CO just

wanted to know why he had been left out of all the fun. “He noticed I didn’t

put him in there,” says Brown. “I told him I was just a cartoonist and I was

fully aware of his rank. Basically, I was trying to avoid jail. He told me to

take it back home, put him in it, and nothing would be said about it.”

When

Brown returned home from the service in 1958, he began driving CTA buses while

attending junior college in the area. He took general classes before enrolling

at the

“They

told me to send the stuff in on 8½-by-11 bond paper, with a self-addressed,

stamped envelope. I had seven good ideas, but eight is a much smoother number,

so I came up with this idea about a little boy standing in the corner holding a

trumpet. His mother tells his father, ‘No, he isn’t being punished, he’s just

imitating Miles Davis.’” The piece was in reference to

“They

sent back the others and told me they were holding that one for further

consideration. I come home a couple of weeks later, and here’s a Playboy envelope with that bunny logo on

it. I take it upstairs and open it, and it says, ‘Dear Mr. Brown, please give

us a black-and-white finish on the following cartoon.’ Man, I went through the

roof!”

Brown

continued coming up with ideas and submitting his work, selling one or two

pieces at a time, sometimes three. “My last year on the bus was 1965,” he says.

“I’d been doing pretty good submitting sporadically; what would happen if I

just sat down and ground them out on a regular basis?”

He

began sending out six to eight ideas per week. The second time Playboy responded, they bought close to

15 pieces, some to be done in black-and-white, some to do in color if he chose,

and some whose gags he would be paid for but the drawing would be assigned to

other artists.

“Hell,

I was a student,” Brown remembered, and with the magazine paying $500 for

black-and-white sketches and $1,000 for color, “anything I didn’t know about

color, I could damn sure learn in a hurry.”

At

the time, Brown was dating a beautiful, fair-skinned co-ed, a

Once

his workload picked up at Playboy, Brown called Mary Ellen and told her he would finally be able to buy her an

engagement ring. She preferred that the two just get married. “I was okay with

it,” he says, “as long as we had a plan — no kids [yet].”

They

married in December of 1965. A few months later, just prior to graduation,

Brown made his first trip to the Playboy mansion.

“They

invited me up there for lunch,” he said. “This is when it was just north of

Division on

Brown

intended to a get a job in advertising after graduation and draw on the side,

but he was persuaded by the magazine to stick with cartooning. He signed on as

a regular contributor and became a member of an elite fraternity of Playboy cartoonists — including Phil Interlandi (“a master of

composition”) and Plastic Man comic creator Jack Cole — selling 20 to 30 cartoons every one or two months.

“Things

worked out pretty good for me,” says Brown. “I didn’t ever think of building a

career with it.” He was also drawing “Sonny and Honey” for Ebony magazine’s children’s offshoot Ebony Jr.!, and doing illustrations for

By

this time, Brown was also a father of two and had his hands full as a

stay-at-home dad. While his wife worked in data processing at Johnson &

Johnson baby products, and later at Panduit Corporation in nearby

“Our

children never came home to an empty house,” says Mary Ellen. “Even when he was

in

Throughout

the ’70s, Playboy flourished,

reaching its circulation zenith of close to seven million in 1975. Granny was

along for the magazine’s success. “Somebody introduced me to a Presbyterian

minister that knew who Granny was,” Brown says in amazement. “There are people

who don’t even read Playboy that know

who she is.”

“It

was so wonderfully shocking back then, this dirty old lady,” says author and

former Playboy articles editor, David

Standish, who would drift in and out of Urry’s 9th floor office in

Brown

liked Granny because she was effective in any setting, as opposed to the

classic buxom, hourglass-shaped female figurine. Sex is sex, but the references

were worlds apart. The inspiration for the character came to him during his

years as a city bus driver. As he would open the doors for new passengers,

Brown was occasionally met by well-intentioned, elderly women asking if he

“went down,” or “Do you go all the way?” He began carrying a sketch book to

document the moments, and the rest of his story — and Granny — became etched in Playboy history.

Starting

out, “I was just trying to be hip,” Brown explains. “I didn’t figure [Playboy] would let me handle any risqué

stuff yet, so I just thought I’d be cute.” Once the work became a steady source

of income, “that’s when the dirty stuff started flowing,” he admits, but he

remained the consummate family man. “I was never one to socialize like that,”

he says. “When my family would go to bed, I would have one more Jack Daniels

and go up myself.”

For

Brown, being a part of Playboy tradition didn’t mean living the life of a playboy. All he wanted to be was a

cartoonist. “I would have drawn for free,” he says. “You could paste my stuff

to my back and I’d jump off of the

But

cartooning is a visual medium, and when it comes to sight humor, it can be

challenging to gauge what is visually going to make someone laugh. The answer

is in the storytelling. Drawing a chuckle has always been Brown’s strong suit,

which he accomplished through the stories told in his panels — and not just

tales of sly, sexual hijinks, but also reflections on cultural issues, which he

did more so than other artists at Playboy.

“When

you draw a cartoon addressing a serious issue,” Standish explains, “you take a

bit of the pressure off of the content. It doesn’t seem as if you’re getting

beat over the head, but the point is still being made. Brown is wonderful at

that.”

And

as Brown wryly shares the fictional title of his autobiography — “How I

Overcame the Obstacles Confronting Me as a Black Man in

“Buck

should be honored because he’s a major survivor out there,” says Neiman, a

former student and instructor at the School of the Art Institute in

*****

“Oh, that’s my sweetie,” Brown says as he hears the

garage door open, signaling Mary Ellen’s return. Their tidy house is filled

with reminders of their six grandchildren: Mother Goose books share space on

the wood and glass coffee table with his wife’s Sudoku puzzles and a copy of O, The Oprah Magazine. Family pictures

and paintings adorn the walls, including one piece done by Brown in 1993 titled

“Journey of Life,” in which a contemporary, five-member black family walks a

circular rut around a grassy mound.

Mary

Ellen Brown, 63, is her husband’s biggest fan. The two have been married for 40

years and have the easy give-and-take of a couple that has been together for a

lifetime.

“Buck,

you need to eat something now,” Mary Ellen insists.

“My

wife stays in my ass,” he laments. “But if it wasn’t for her, I’d be pushing up

daisies somewhere.”

Brown

suffered a heart attack in 1996 and a stroke in 2000, both complications from

diabetes. He awoke one morning in 2005 to blurred vision in a left eye filled

entirely with blood, leading to cataract surgery later that year. He attends

physical therapy and diabetes education classes multiple times a week. “Every

time I turn around,” says Brown, “something else has gone clunkety.”

Mary

Ellen has planned for her husband’s life after Playboy. The two are a true right-brain, left-brain pairing — he is

the creative half, while she focuses on facts and figures. “We’re opposites in

that way,” says Mary Ellen, a mathematics major at the

Brown

spends his days painting and keeping up with health classes and doctor’s

appointments. An avid golfer for 40 years, he plans to get back out on the

links as soon as doctors give him the green light. He also has his wife’s

agenda to stick to.

“She’ll

be out and call home and tell me not to leave because we’re going to do this or

that,” he says. “She retired, and then she wanted me to retire with her.”

He

rises from the couch, hesitates and trembles slightly before walking. A second

or two passes before he can even take a step. Brown does still paint, although

his current work is more reflective of classic and contemporary themes of

everyday African-American life, and not the sophisticated bathroom-wall humor

put forth in his work for Playboy. Behind him are the days of drawing cartoons of God asking Adam to pull his

finger on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, or Granny complaining to an old

companion that, “You never sock it to me anymore.”

“I

have a few paintings I want to get back to,” says Brown, “if the doctors will

let me go.” Medical obligations interfere with a schedule that used to allow

him to paint long into the night and sleep during the day. “Getting up and

getting ready and going to see these doctors and stuff like that — why bother?”

Mary

Ellen feels that if he manages his diabetes, he could develop a regular

painting routine.

“The

fewer doctors he has to see, the more time he has for his work,” she explains.

“That’s what this [diabetes] training is all about, for him to know what he has

to do to stay healthy, then for him to do it. Then, he can cut out a lot of

doctors.”

Brown’s

health problems might just be a temporary setback, but frustration and

intransigence won’t let him see it. Fortunately, his wife does. “Buck’s always

said he’s never going to retire. He’ll always be an artist.”

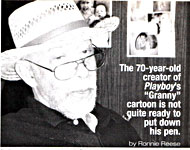

A Granny Gallery

Here’s a short helping of Buck Brown’s work from the pages of Playboy and elsewhere. The first picture is a self-caricature Brown did for collector Mark Cohen in which the cartoonist is doing a “buck” and Granny is doing the “winging” with a red-hot pistol, calling the tune, you might say. (This drawing is taken from that book I did with Mark, A Gallery of Rogues: Cartoonists’ Self-caricatures, about which you can learn more by clicking here.) Then come some Playboy cartoons, including a couple Grannys and an illustration (old guy chained to the wall), followed by a copy of a halftone photo of Brown at the age of 70 that appeared in Who-Ville; and then, the final picture, another Brown self-caricature, this one done for Mark Cohen’s “nude self-caricatures by cartoonists” project (see Opus 213 for details about this inspired nonsense).

As a concluding example of Reese’s journalism, here’s

an autobiographical squib I asked him to supply:

Ronnie

Reese is a native of

Undaunted,

Reese continues to make somewhat of a career in journalism as a regular

freelance contributor to Wax Poetics and Stop Smiling magazines, in addition to

alternative weeklies in the San Francisco-Oakland Bay area, the Audiversity.com

audio blog, and other publications that seem to sprout daily. He is also a

member of the National Association of Black Journalists and an alumnus of the

Academy for Alternative Journalism at the Northwestern University Medill School

of Journalism and Integrated Marketing Communications.

Despite

still having to work the much-maligned corporate day job, Reese has found that

writing is—and will always be—his true passion. But the greatest lesson for him

came not from his co-worker at the Tribune,

but from words spoken by actress Lily Tomlin, who is also no stranger to the

“Nine to Five” way of living. “I always wanted to be somebody, but now I

realize I should have been more specific.”

Reese

can be reached at reeseronnieL@hotmail.com

|

|||||||||||

But Brown was also an important cartoonist

historically: he was one of the first African-American cartoonists to achieve

national circulation in mainstream media. His first cartoon for Playboy was published in March 1962,

putting him in equally important company: syndicated comic strip cartoonists Morrie Turner (Wee Pals), Brumsic Brandon

Jr. (Luther) and Ted Shearer (Quincy), all African-Americans, made it into mainstream newspapers

during the same decade as the civil rights movement was gathering

momentum—Turner in 1965, Brandon in 1968, and Shearer in 1970. But Brown was

different: his cartoons didn’t usually feature any racial minorities and they

weren’t usually about race. Like the magazine cartoons of E. Sims Campbell, another African-American gag-panel cartooner who

debuted in Esquire’s first issue in

the fall of 1933, Brown’s cartoons were about sex, usually, and sometimes about

some of the other “entertainments for men,” Playboy’s self-proclaimed turf. Golf, for instance: Brown was an avid golfer. Turner,

Brandon, and Shearer all dealt the race card, so to speak; Brown didn’t. Not as

a general rule. He sometimes turned to racial issues, as Playboy’s obituary notice (above) indicates. And when he did, said

Michelle Urry, the magazine’s long-time cartoon editor, “he rendered the most

incisive comments on race relations in

But Brown was also an important cartoonist

historically: he was one of the first African-American cartoonists to achieve

national circulation in mainstream media. His first cartoon for Playboy was published in March 1962,

putting him in equally important company: syndicated comic strip cartoonists Morrie Turner (Wee Pals), Brumsic Brandon

Jr. (Luther) and Ted Shearer (Quincy), all African-Americans, made it into mainstream newspapers

during the same decade as the civil rights movement was gathering

momentum—Turner in 1965, Brandon in 1968, and Shearer in 1970. But Brown was

different: his cartoons didn’t usually feature any racial minorities and they

weren’t usually about race. Like the magazine cartoons of E. Sims Campbell, another African-American gag-panel cartooner who

debuted in Esquire’s first issue in

the fall of 1933, Brown’s cartoons were about sex, usually, and sometimes about

some of the other “entertainments for men,” Playboy’s self-proclaimed turf. Golf, for instance: Brown was an avid golfer. Turner,

Brandon, and Shearer all dealt the race card, so to speak; Brown didn’t. Not as

a general rule. He sometimes turned to racial issues, as Playboy’s obituary notice (above) indicates. And when he did, said

Michelle Urry, the magazine’s long-time cartoon editor, “he rendered the most

incisive comments on race relations in