|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 425 (February15, 2022): We report on book bannings in schools nationwide (starting with the Pulitzer-winning Maus) and review the final book in the Complete Peanuts series (which covers miscellaneous Schulz cartoons) and The New Yorker’s cartooning failures and a long farewell to Ron Goulart, plus the usual book and comicbook Number Ones reviews. In order to assist you in wading through all this plethora, we’re listing Opus 425's contents below so you can pick and choose which items you want to spend time on. An asterisk* marks the longest items. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order, beginning with the news of the day—:

NOUS R US The Summer’s Superhero Movies Black Comics Festival All Virual Another Staff Editoonist Disappears The One That Got Away Geppi’s Diamond At Its Sparkling 40th Minnie Gets Pants ODDS & ADDENDA

**PULITZER WINNING GRAPHIC NOVEL IS BANNED Editoonist Outraged Novel Supported Other Bannings of Graphic Novels and Comics

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body She-Hulk No.1

EDITOONERY GasBag Legions: An Essay Then, Short Sample of the Month’s Editoons

Year’s Top Toons *Ann Telnaes Daryl Cagle

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Time Covers of the Prez Caricatures of the Prez Pin-Ups from the Previews Catalog

BOOK MARQUEE The Life and Comics of Howard Cruse Tom the Dancing Bug Without the Bad Ones

BOOK REVIEWS *The Complete Peanuts: Comics and Stories, 1950-2000

*BOTTOM LINERS The New Yorker’s Christmas/Cartoon Issue Plus, the Anniversary Issue

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Friday, Book One: The First Day of Christmas

PASSIN’ THROUGH **Ron Goulart *Orlando Busino Sidney Poitier James Bond

And More Yet on Ron Goulart

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND— “If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

THE SUMMER’S SUPERHERO MOVIES Mark Meszoros at the Ohio News-Herald starts off his review with this: “So — you’re, um, not tired of superhero movies yet, are you? No? Phew. This could have been awkward. For what feels roughly like the thousandth year in a row, other-worldly beings are at the heart of many of the most noteworthy of the releases of the next 350-plus days.” Right. It looks like the spandex crowd has taken over the motion picture industry. Here are 10 of the species you can expect to see over the next few months. ◆ “The Batman” in March with Robert Pattinson as Bruce Wayne et al. “Something delightfully—and dirtily—distinct.” ◆ “Morbius” (April) from the Marvel Comics Universe, “vampiric ramifications.” ◆ “Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness” (May) with Benedict Cumberbatch as the doctor. ◆ “DC League of Super Pets” (May) animated animals. ◆ “Thor: Love and Thunder” (July) into which Christian Bale drops as Gorr the Butcher, “who certainly sounds like someone who will be a thorn in Thor’s side.” ◆ “Black Adam” (July) Dwayne Johnson as the antiheroic thorn in Captain Marvel’s side. Well, in the old comicbooks anyhow; dunno about this. But I was always thrilled when he showed up to rattle Captain Marvel’s cage. ◆ “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Part One)” (October) wherein the success of “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” calls forth a two-part sequel. ◆ “The Flash” (November) into which Michael Keaton insinuates himself as Bruce Wayne/Batman; Ezra Miller is Barry Allen/The Flash. ◆ “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” (November) Disney/Marvel Studios apparently chose against re-casting the title role. So it’s a movie about Black Panther without Black Panther? ◆ “Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom” (December) will doubtless find the Lost Kingdom in the ocean depths. I never liked Aquaman much back in the day; but DC has improved him.

BLACK COMICS FESTIVAL ALL VIRUAL The Schomburg Center Black Comic Book Festival has for a decade brought together animators, Blerds, bloggers, cosplay lovers, fans, families, illustrators, independent publishers, and writers to celebrate Black comicbooks and graphic novels, and it provides a platform to get the works directly to readers. This annual event features panel discussions, workshops, cosplay showcases, and highlights the work of creators from across the country. The tenth annual festival was January 13-15 and was an all virtual event due to the continuing threat of COVID. Patrons could register for events and panels online. The exhibition, “Boundless: 10 Years of Seeding Black Comic Futures,” will be on display at the Schomburg Center, 515 Malcolm X Blvd, New York, NY starting January 14, 2022.

ANOTHER STAFF EDITOONIST DROPS OUT Editorial cartoonist Mike Thompson has taken (what D.D. Degg interprets as) a buyout offer from Detroit Free Press/USA Today /Gannett. At his dailycartoonist.com, Degg quotes Thompson’s Facebook page: “After

35 years as a staff editorial cartoonist, I’m getting out on the top floor. USA Today has eliminated my editorial cartooning position and giving

me a very nice parting gift, so for the immediate future I’ll be focusing on

the comic strip, Grand Avenue, that I’ve been producing for years. I’ve

spent the last two weeks at USA Today finishing up projects and entering

contests in anticipation of a month-long break.” Thompson will eventually return to editooning but on a freelance basis. “Mike expands on his departure from staff,” Degg says, again quoting Thompson: “This is not disagreeable to me. I’ve been doing two jobs for a decade-and-a-half and will now be doing one. When you’re approaching 60, that’s a life-saver. And I will get to create work, on a freelance … good income base. None of this would be possible if I weren’t married to someone with who earns more and has better insurance. (Thanks, Hon!) The timing of all this works well with where we are in life.” “If my reckoning is correct,” Degg said, “this leaves Andy Marlette as the only staff cartoonist on a Gannett newspaper. Mike will continue to have a daily deadline for his Grand Avenue comic strip.” Grand Avenue was launched in 1999 by another editoonist, Steve Breen, a two-time Pulitzer-winner. The strip, which was at one time syndicated to about 100 newspapers, chronicles the lives of Kate Macfarlane and her two grandchildren, as the active and untraditional grandmother raises mischievous twins Gabby and Michael. Thompson started work on the strip in 2005, joining Breen. In April 2016, Thompson took on Grand Avenue by himself and began solo signing it. Grand Avenue avoids politics. “Steve started, and I’ve continued, the tradition of keeping it nonpolitical,” Thompson once said. “By the time I’m done drawing about politics, I’m tired of the tough topics, and there are so many other things in the world to draw about, interesting topics on the relations between humans and things that aren’t political in nature, but are funny and quirky and make for great cartoon fodder.”

Playboy Expires THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY This one slipped by us: in March 2020—two years ago!— Ben Kohn, CEO of Playboy Enterprises, announced that the Spring issue of Hugh Hefner’s notorious magazine would be the last regularly scheduled printed issue and that Playboy would now publish its content online. The decision (it sez here) to shut down the print edition was attributed in part to the COVID-19 pandemic which interfered with distribution of the magazine. That was merely the straw that broke the camel’s back. The magazine has been losing money for years, as much as $7 million/year lately. It’s about the only thing in Playboy Enterprises that doesn’t make money. And the present ownership of Playboy Enterprises expects profit; so they eliminated the most consistent money-loser in their control. And so, for all practical purposes, Playboy is over. Wouldn’t have happened—in fact, didn’t happen—while Hef was alive. We’ll review the magazine’s history and publish a gallery of its cartoons in a future Opus (No.427 most likely). Until then, you might commemorate the two-year-old disaster by reading the biography of founder Hugh Hefner at Harv’s Hindsight for October 2017; or visit Opus 349 for a review of the “no nudes” fiasco a couple years back; or go back to Hindsight, this time for November 2003, and read about Jack Cole, whose water-colored cartoons set the bar for Playboy cartoonists.

GEPPI’S DIAMOND AT ITS SPARKLING 40TH Diamond Comics Distributors celebrated its 40th anniversary on February 1, and Heidi MacDonald took notice at comicsbeat.com. ... “Love ’em or hate ’em, founder Steve Geppi is one of the most colorful and key figures of the era, and Diamond is one of the most important companies in comics history – and I can’t think of another business where common fans keep up on the inner workings of a primary distributor. That’s the way the community of comics works. “It’s been an up-and-down few years for Diamond, but they’re still here and say what you will about the company, Diamond does care a lot about comics and the people who make and sell them. I know that from my own decades talking to the hard working men and women who run the company. So on this day, I wish them a hearty Happy Birthday.” Heidi then quotes part of the Diamond press release, and we’re quoting even less but with our congratulations still: “On February 1st of 1982, President and CEO, Steve Geppi, transitioned from local retailer to comic book distributor with one warehouse and seventeen customers. Forty years later, Diamond has grown into the largest distributor of English-language comic books, graphic novels, and related pop culture merchandise worldwide.”

MINNIE GETS PANTS Minnie Mouse will be sporting a blue pantsuit to celebrate Women’s History Month and Disneyland Paris’ 30th anniversary. Originally the pantsuit helped women blend into male-dominated spaces, says Kim Elsesser, who covers the intersection of business, psychology and gender for Forbes, “but the pantsuit has now become a symbol for women’s empowerment.” For the 30th Anniversary of Disneyland Paris, British designer Stella McCartney created Minnie’s first pantsuit which will be worn at the Paris theme park. Said McCartney: “I

wanted Minnie to wear her very first pantsuit at Disneyland Paris, so I have

designed one of my iconic costumes, a blue tuxedo, using responsibly sourced

fabrics. This new take on her signature polka dots makes Minnie Mouse a symbol

of progress for a new generation. She will wear it in honor of Women’s History

Month, in March 2022.” I’m glad the fabrics are responsibly sourced. Then Elsesser rushes in with a short history of power symbols. “For centuries, the suit has been a symbol of male power. A few women in elite circles in the 1930s began wearing pantsuits (think Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich), but until the 1950s women could be arrested for wearing pantsuits for ‘impersonating a man.’ By the 1960s, pantsuits had a slightly broader appeal, but it wasn’t until 1993 that women were even allowed to wear pants on the U.S. Senate floor. Carol Moseley-Braun and Barbara Mikulski were the first women to break with this tradition: they wore pantsuits on the Senate floor and got the dress code changed.” Elsesser goes on: “Hillary Clinton’s pantsuits became famous after her historic run for the presidency. In her book, What Happened, she describes why the pantsuit was her outfit of choice. ‘They make me feel professional,’ she writes, adding she also felt the pantsuit helped her fit in with the other male politicians.” No, not “other male politicians”; that would mean Hillary is also male. Geez. Just can’t get good help these days. Back to Minnie. It’s not clear from what Elsesser says if Minnie’s wearing of a pantsuit will happen only for the 30th anniversary of Disneyland Paris. Elsesser can give us the history of the pantsuit but can’t seem to focus on the news at hand.

ODDS & ADDENDA To celebrate the opening of the 25th season of “South Park” on February 2, creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone assembled a group of Broadway stars, along with a 30-piece orchestra, to perform the series’ classic tune “Kyle’s Mom’s a Bitch.” ... Peter Robbins, whose voice brought Charlie Brown to life in Peanuts tv shows in the 1960s but who struggled with mental illness and served prison time later in his life, died January 18.

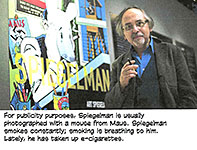

SCHOOL BOARD BANS PRIZE-WINNING GRAPHIC NOVEL And That’s Just the Tip of the Iceberger A Tennessee school board barred schools from teaching Maus, a Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, in an unanimous vote that was taken, ironically, on the day before Holocaust Remembrance Day. Officials objected to eight instances of profanity, “Goddamn,” and a drawing of a naked female, reported Blake Montgomery at dailybeast. com. Members of the McMinn County school board said the ban was not related to the book’s depiction of the Holocaust as it tells the story of author Art Spiegelman’s parents in German concentration camps, with Jews depicted as mice and Nazis as cats. The female nude was, therefore, a naked cartoon mouse—but, admittedly, with a human body. Spiegelman, asked about the ban, said he was “baffled” by it, calling the school board’s decision “Orwellian.” “It’s leaving me with my jaw open, like, What?” he said. In the current sociopolitical climate, he views the Tennessee vote as no anomaly. “It’s part of a continuum, and just a harbinger of things to come,” Spiegelman told Michael Cavna at the Washington Post, adding that “the control of people’s thoughts is essential to all of this.” As

such school votes strategically aim to limit “what people can learn, what they

can understand and think about,” he says, there is “at least one part of our

political spectrum that seems to be very enthusiastic about” banning books. “This is a red alert. It’s not just: ‘How dare they deny the Holocaust?’ ” he says with a mock gasp. “They’ll deny anything.” The decision, says reporter Montgomery, comes as conservative officials across the country increasingly have tried to limit the type of books that children are exposed to, including books that address structural racism and LGBTQ issues. Board member Tony Allman is quoted by the Associated Press: “It shows people hanging. It shows them killing kids. Why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff? It is not wise or healthy.” Jeet Heer at jeetheer.substack.com quotes another board member, Mike Cochran, as saying: “I thought the end was stupid to be honest with you. A lot of the cussing had to do with the son cussing out the father, so I don’t really know how that teaches our kids any kind of ethical stuff. It’s just the opposite, instead of treating his father with some kind of respect, he treated his father like he was the victim.” The scene Cochran is describing is from the end of the first volume of Maus, where Spiegelman learns that his father had destroyed his late mother’s diaries. Those diaries are important for many reasons, not least because Spiegelman’s mom committed suicide and the diaries might provide clues as to the experiences that led to that tragedy. Art is enraged and fights with his father, saying, “God damn you!” Art yells. “You – you murderer! How the hell could you do such a thing!!” This is no doubt a harsh scene, Heer says. “It’s also one of the crucial moments in the book, because it shows how the Holocaust shaped the Spiegelman family long after it was over, leaving them with all sorts of unprocessed traumas and fights over memory. To have a scene where the son was dutifully respectful of the father at all times would have been a lie and it would also have destroyed the human meaning of the book, the honesty that made it speak to so many readers.” The board members spent a lot of time talking about what they call the “nude scene.” Tony Allmann in particular is hung up on the fact that Spiegelman once, in the late 1970s, drew cartoons for Playboy: “I may be wrong, but this guy that created the artwork used to do the graphics for Playboy,” Allman says. “You can look at his history, and we’re letting him do graphics in books for students in elementary school. If I had a child in the eighth grade, this ain’t happening. If I had to move him out and homeschool him or put him somewhere else, this is not happening.” Says Heer: “It’s hard not to escape the suspicion that Allman is conflating graphic novel with the phrase ‘graphic sex.’ “This all puzzled me because I didn’t remember anything salacious in Maus at all. New York Times reporter Joan Coaston solved the mystery by noting that the ‘nudity’ in Maus is a scene were the prisoners in Auschwitz are stripped naked and beaten.” And they’re all mice, remember. The U.S. Holocaust Museum tweeted that “Maus has played a vital role in educating about the Holocaust through sharing detailed and personal experiences of victims and survivors. Teaching about the Holocaust using books like Maus can inspire students to think critically about the past and their own roles and responsibilities today.” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said: “Yes, it is uncomfortable to talk about genocide, but it is our history and educating about it helps us not repeat this horror.” Spiegelman has been approached at least four separate times over the years to turn Maus into a movie, but has flatly refused. “I like movies, but Maus is better served as a book,” Spiegelman says. “[It’s a] more intimate form and comics adhere to the brain better.” He

has also turned down millions of dollars in licensing and merchandising deals

relating to Maus iconography. The Complete Maus, which is a two volume production, reached the top position on Amazon’s best-seller list Monday, January 31st. A discussion of the Maus banning on tv’s “The View” also led ABC to suspend co-host Whoopi Goldberg for two weeks after she said the Holocaust “isn’t about race.” To Goldberg, a Black person, “race” has always to do with skin color. Later, she realized that not everyone thinks of “race” that way. “I get it,” she said, and she apologized. At The Comics Journal website, tcj.com, you can find the transcript of the discussion at the McMinn school board meeting that resulted in Maus being banned. Reading it is an education in how simple-minded some of our good citizens are. It’ll make you blink. Here’s the link— https://www.tcj.com/transcript-of-the-mcminn-county-board-of-educations-removal-of-maus/ Editoonist Outraged Over Maus Banning

Maus is a graphic novel by Art Spiegelman about the Holocaust. It’s very dark and disturbing, you know, because it’s about the Holocaust. A proxy for the author is a mouse who interviews his mouse father about his experience in the Holocaust. The Nazis are depicted as cats. The McMinn County School board in Tennessee has pulled the book from the eighth-grade curriculum because they believe either eighth-graders are too young to learn about the Holocaust or they want to protect Nazis because 60 percent of the country are Trumpers, or they’re all cat people. Trip advisors advise that the National Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. is fine for 12-year-olds, though there are parts of the museum that has been determined safe for ages as young as eight. I think kids in the eighth grade would be fine with learning about the Holocaust from Maus. In fact, I think that’s an excellent way to start being educated on the subject. Besides, kids in the eighth grade have the Internet. They all have smartphones. Okay, maybe not in Hooterville, Tennessee, but I bet they at least have Animal Planet and they’ve seen how giraffes jump on top of each other. I bet half of them have seen “Inglourious Basterds.” If they can handle giraffe sex and Brad Pitt bashing Nazis’ brains in with baseball bats, then they can handle Maus. Can the school board in Tennessee at least appreciate the irony of banning books about people who banned books? Hello? Is anyone home? The Tennessee troglodytes aren’t the only thuglicans running amuck. Neil Young has been standing on his principles for decades, long before Joe Rogan realized he could turn a failed acting career into a successful racist conspiracy-theory-spreading podcast career. And now, the troglodytes have canceled Neil Young in favor of Joe Rogan. Many years ago, Mr. Young wrote a song called “Southern Man” which covered racism in the southern United States. The song was so strong that it pissed off Lynyrd Skynyrd who wrote the greatest answer song in music history, “Sweet Home, Alabama.” Funny enough, there was never a feud between Young and Skynyrd. They had fun taking shots at each other but were actually friends and fans of each others’ music. Lynyrd Skynyrd defended the south, but also wrote their share of anti-racism songs, and at least one anti-gun song. I digress. The point is, Neil Young has principles. Now, Spotify is singing it doesn’t need Mr. Young around anyhow because Old Neil put her down. Neil Young demanded that Spotify remove his music from their service unless they removed Joe Rogan’s racist and ignorant podcast, which Spotify had just signed to an exclusive multi-gazongo million-dollar deal. Rogan’s podcast is wildly popular and might be the number-one podcast in the nation, and in close competition with Steve Bannon’s among racists. Neil Young has written great music for decades and has influenced bands like Pearl Jam, but it’s not like the kids are buying his albums anymore. C’mon, he’s 76. So, guess which one Spotify picked. Despite moving poisonous content from its platform in the past, Spotify chose to stick with Rogan and his racist conspiracy theories. Did you catch the show earlier this week when white Joe Rogan led a rant explaining what does and does not define a Black person? According to Rogan, they can only come from the “deepest and darkest” places of Africa. But yeah, Spotify kicked Mr. Young to the curb. But so what? Give us some more of those Rogan explanations why African Americans aren’t black people, Spotify. That’s good stuff (this is heavy sarcasm, slow kids). Of course, all the cancel-culture whining mofos are in euphoria over this. They’re still pissed off at Mr. Young for denigrating racists in “Southern Man.” I’m a casual fan of Neil Young’s music. I’m a bigger fan of the person he is. I was in a band once that played a pretty good version of “Down by the River” and I was in another band that played a crappy version of “Rocking in the Free World.” I love a lot of his music, most of all, “Harvest Moon,” which I covered all by myself on acoustic guitar. Neil Young kicks ass. I just realized that I’m not a casual fan of his music. I’m a huge fan. And being a sloppy guitar player, I should be. Neil Young has what we’re lacking in this nation. Principles, ethics, and dignity. He stood his ground and lost money. Spotify traded in its principles for profit and in the process, contributed so much ignorance and poison to the nation. And who said the Swedes can’t be capitalists? Ban books? We need to bring in more books that are disturbing and educational. We need more education, not less. There are too many Joe Rogans out there and not enough Neil Youngs. Hey, have the Tennessee goons banned Neil Young’s “Southern Man” yet? I hope Spotify will remember that a cartoonist man don’t need them around anyhow.

Signed Prints. Clay Jones is selling signed prints of his cartoon at the top of this article for just $40.00 each at his website, claytoonz.com Every cartoon on this site is available. You can pay through PayPal. If you don’t like PayPal, you can snail mail it to Clay Jones, P.O. Box 3721, Fredericksburg, VA 22402. Clay says he can mail the prints directly to you or if you’re purchasing as a gift, directly to the person you’re gifting.

COMICBOOK STORE GIVES AWAY MAUS In reaction to the McMinn County school board banning, a Knoxville comicbook store announced on Thursday, January 27, that it would begin giving away free copies of Maus for students who want to learn more about the Holocaust. The WBIR staff reported that Nirvana Comics owners said they would give away copies of the book because they "believe it is a must-read for everyone." They said all students need to do is ask for a copy by calling them or reaching out on social media. However, they said they had a limited supply of books so there could be a waitlist for anyone interested in reading it. They said they had a large order of Maus expected to arrive soon, so they could give away more copies of the book after their initial supply was loaned out or sold. "We are in discussions with a much larger organization to expand the program. We hope to have news on that soon," they also said. Anyone who wants to help with Nirvana Comics' program can also donate. They said they are looking into crowdfunding platforms to better organize donations. On Friday, they launched a campaign on GoFundMe. Nirvana Comics can be reached at 865-200-5067 or online. And other responses to the Maus banning prompts good news—; Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com reports that a live reading of Maus followed by a conversation about the book and its subject was scheduled for February 3 at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in downtown Athens in McMinn County, thumbing its nose at the action of the McMinn school board. All the publicity about the banning has sparked sales of the book, Johnston says. Forty-two years after it was first released, Maus is currently the twelfth best-selling graphic novel on Amazon.com for Book One, and 13th for the Complete Maus.

FLORIDA CONSIDERS BANNING BESTSELLERS Polk County in Florida is the latest to be subject to banning of the critically acclaimed bestselling graphic novels from schools, part of a series of such exclusions in recent years that Bleeding Cool has covered. At bleedingcool.com, Rich Johnston reports that Polk County Public Schools Superintendent Frederick Heid has asked middle and high school librarians to remove 16 books from schools for a review, after receiving complaints about the books from the activist group County Citizens Defending Freedom. Among the withdrawn books is Drama by Raina Telgemeier, one of the bestselling graphic novels of recent times, from 35 locations. The graphic novel is a coming-of-age story involving the crew of a middle school musical that has won both praise and criticism for its LGBTQ portrayal. But the affected books are not banned: they are being reviewed in response to complaints and may, eventually, be banned. Or cleared and put back in circulation again. County Citizens Defending Freedom describes itself as "an organization that empowers and equips American citizens to defend their freedoms and liberties at the local level. By streamlining and simplifying activism, we support and champion American citizens who want to stand up for their independence. To equip and empower American citizens to stand for and preserve freedom for themselves and future generations. To resolve breaches of freedom and liberty through local awareness, local light, and local action." And a vision to "see CCDF-USA affiliates spread organically in counties across America. To become the inspiration and action arm of local citizens to defend their faith, freedom, and liberty, while placing local governance under the watchful eye of local American citizens acting as patriots." In this case, says Johnston, that means fighting for the freedom to pull books from school shelves and against the freedom for kids to read them. And by pure coincidence, the sixteen titles named include gay themes like Drama or tackle racism. Superintendent Heid told LKLD Now that the group's members allege the books contain material harmful to minors which would violate Florida statute 847.012, which involves distribution of "harmful materials" to minors. "While it is not the role of my office to approve/evaluate instructional or resource materials at that level,” said Heid, “I do have an obligation to review any allegation that a crime is being or has been committed. It is also my obligation to provide safeguards to protect our employees." The named books are—:

Drama by Raina Telgemeir Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison The Kite Runner by Khaled Hossein Beloved by Toni Morrison Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer The Vincent Boys by Abbi Glines It's Perfectly Normal by Robert Harris, illustrated by Michael Emberley Real Live Boyfriends by E. Lockhart George by Alex Gino I am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult More Happy Than Not by Adam Silvera Tricks by Ellen Hopkins Almost Perfect by Brian Katcher

NATION-WIDE EFFORTS TO BAN BOOKS By Elizabeth A. Harris and Alexandra Alter at the New York Times In Wyoming, a county prosecutor’s office is considering charges against library employees for stocking books like Sex Is a Funny Word and This Book is Gay. In Oklahoma, the state Senate is considering a bill that would prohibit public school libraries from keeping books on hand that focus on sexual activity, sexual or gender identity. Parents, activists, school board officials and lawmakers around the country are challenging books at a pace not seen in decades. The American Library Association said in a preliminary report that it received last fall an “unprecedented” 330 reports of book challenges, each of which can include several books. But it’s not just the frequency of such challenges. Fueled by social media and a national divisiveness, conservative groups are now pushing their challenges into statehouses, law enforcement and political races. “The politicalization of the topic is what’s different than what I’ve seen in the past, “ said Britten Follett, chief executive of content at Follett School Solutions, one of the country’s largest providers of books to K-12 schools. The most frequent targets are books about race, gender and sexuality, “including oral sex and anal sex, and,” says the founder of Moms for Liberty, “— children are not ready for that kind of material.” Parents, she goes on, should not be vilified for questioning the appropriateness of a book—without considering the book. George M. Johnson, author of All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir about growing up Black and queer, was stunned in November to learn that a school board member in Florida and filed with the sheriff’s department a complaint against his book. “I didn’t know that was something you could do—file a criminal complaint against a book,” Johnson said. So far, efforts to bring criminal charges against librarians and educators have largely faltered. And courts have generally taken the position that libraries should not remove books from circulation. But the fussin’ goes on.

THE ADVOCACY GROUP NO LEFT TURN IN EDUCATION maintains list of books it says are “used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.” Some groups say prohibiting books violates the rights of parents and the rights of children who believe access to books is important. Book challenges aren’t coming just from the right: Of Mice and Men and To Kill a Mockingbird, for example, have been challenged over the years for how they address race, and both were among the Library Association’s 10 most-challenged books in 2020. A school district in Washington state voted last month, at the request of staff members, to remove from the ninth-grade curriculum To Kill a Mockingbird—voted the best book of the past 125 years in a survey of readers conducted by the New York Times Book Review. Objections to the book included arguments that it marginalized characters of color, celebrated “white saviorhood” and used racial slurs dozens of times without addressing their derogatory nature. Politicians on the right have seized upon the controversies over books, exploiting them for political advantage. The newly elected governor of Virginia, a Republican, rallied supporters by framing book bans as an issue of parental control. In Texas, Governor Greg Abbott demanded that the state’s education agency “investigate any criminal activity in our public schools involving the availability of pornography,” a move that might make librarians fear might make them targets of criminal complaints. The governor of South Carolina asked the state superintendent to investigate the presence of “obscene and pornographic” materials in its public schools, offering Gender Queer as an example of a questionable book. The mayor of Ridgeland, Mississippi recently withheld funding from the school library system, saying he would not release the money until books with LGBTQ themes were removed. At The Week, we learned last year that when Dr. Seuss’ publisher stopped printing one of his older books because of its racial stereotypes, Fox News and Republicons cried “cancel culture!” But unashamed of their hypocrisy, conservatives in 30 states are now seeking to root out books from classrooms and school libraries that offend them “in what experts are calling a historic and concerted book-banning effort.” ... GOP activists, school boards, lawmakers, and governors across the nation quickly got in on the action, issuing orders and crafting legislation to protect kids from books that discuss racism, sexuality, feminism, and other “dangerous” topics. The ongoing “frenzy” of right-wing censorship is the largest since the 1920s campaign against teaching evolution. ... In Texas, GOP state Representative Matt Krause is investigating a list of 850 books for their potential to cause “discomfort.” ... Parents are objecting to their kids being taught that biological sex is an illusion, that America is inherently racist, that “whiteness” is evil, and the other far-left tenets of “critical race theory.” ... And over time, both the Left and Right have sought to remove novels and texts for ideological reasons. ... In the New York Times, Viet Thanh Nguyen said it’s the potential of books to be “dangerous”—to our preconceptions, our complacency, our circumscribed empathy—that makes them so vital. A society that starts banning books to avoid discomfort is headed “to the wrong destination.”

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Like a velvet glove cast in iron—the name of a graphic novel by Dan Clowes. I just like the imagey. The thing about peeling an orange is that it postpones gratification. Eventually, you grow to like peeling better than eating, at which point, we may say the orange has won.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

BECAUSE I DON’T LIKE TO LEAP to conclusions, I have refrained from telling myself that Oswald’s body in Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body is the body of Lee Harvey Oswald, killer of Prez John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. But by the end of the first issue, it’s clear that the Oswald at issue is indeed the Lee Harvey one. Not that there aren’t plenty of hints long before we get to the end. I just don’t like leaping, as I said. The book opens with page of text on Doppelgangers or Doubles. Then we have some sort of organization chart, littered with cross-outs except for the names Jack Ruby and Lee Oswald, the latter name connected to the word “decoy.” On the next page, the visuals begin with a picture of a decaying body in a coffin. Several people are digging up a grave and removing the body to take it somewhere to confirm or deny a rumor that the body isn’t “him.” To leap, finally, to some conclusions that aren’t yet apparent, presumably “he” is Oswald, murderer of JFK, and there’d been a body switch: Oswald was never dead. Then

we watch a miserably unsuccessful ($81) bank robbery on November 8, 1963. The

robber is disappointed to learn his robbery hasn’t made it into the news of the

day. He goes to his motel, and when he goes to bed, his slumber is distrubed by

the arrival of Frank, a big guy, who barges into his room and offers Shep (the

robber) a job. Next we meet Buck Willy, a troubadour in a bar about to sing but he’s boo’d offstage. Outside in the parking lot, Frank shows up and offers Buck a job. Also November 8, 1963. Then, still 1963, we meet college-age Wainright, a failure at everything but shooting a gun, and he’s a marksman. Frank shows up and offers him a job. Then Frank gets Rose out of jail; then he takes her to meet the rest of his gang. They’ve been selected for their individual talents: Shep, who’s good at escaping the consequences of his actions, can “get them in and out”; Buck can drive the car; Wainright has the firepower, and Rose is good at forging documents. Frank

shows them a photo of Harvey Oswald and tells them their job is to find someone

who looks like Oswald—a doppleganger. With the emergence of the photo, we

realize that this tale is about Lee Harvey Oswald. The book is a cascade of episodes—each one re-introducing Frank; and each one establishing the ability of the authors (writer Christopher Cantwell and illustrator Luca Casalanguida) to build and sustain suspense. Casalanguida’s drawing style deploys a crisp outline with lines of moderate thickness; then, as required for some scenes, he edges his pictures with chips of solid black, modeling the forms. Nice. They stage the action expertly and create visual variety by varying camera angle and distance. The second issue opens with a diagram of city streets and the floorplan of an office. (Or a warehouse?) The opening page is dated October 5, 1981 in Dallas in a hospital where people are inspecting the body we saw unearthed last time. They’re comparing it to the statistical Lee Harvey Oswald. Then we go back to November 21, 1963, and Frank’s quartet, Shep, Buck, Wainright, and Rose in a car in a parking lot outside Lovers Lane Bar, waiting for something to happen. When it does, it takes the shape of a guy being booted out of the bar. This guy, whose name is Sonny Germs, Frank tells the foursome they must kidnap—for which deed, they’ll each be paid $4K. They do it. They tie him up. He subsequently gets loose and points a shotgun at them. They all four jump on him and Buck chloroforms him into unconsciousness. They tie him up in a house and phone Frank, who tells them to let Wainright shoot the guy on the left side of the adomen right in the lower ribs —point blank —for $10K. When they find out, they’re all disturbed about it. They didn’t hire on to commit murder. A propos of nothing, we see Oswald with rifle at a window in the schoolbook building. But before anything else can happen, Germs gets loose again and runs off. Rose pursues in a car and in the ensuing action, Germs is killed when Rose accidentally runs the car into him. And at that moment, as they stare at Germs’ body, they learn JFK has been shot in downtown Dallas. There the book ends with the facing page, completely blank except for the words “Who the fuck is JD Tippit?” followed by a diagram that shows inside Dallas Police Dept, with Oswald’s route marked; ditto Jack Ruby’s route. This is enough to give you bad dreams at night.

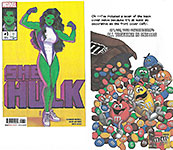

SHE-HULK, back

in her own title, gets the cover of No.1 all to herself. And the cover, by Jen

Bartel and Adam Hughes, is the best thing about the issue, which Jen

Walters spends mostly worrying about her lack of wardrobe. Then Jen goes to a job interview with Mallory Book (former Miss Utah and “the best lawyer in New York”), who promptly hires her without even conducting an interview. Jen is now late for her meeting with Janet Van Dyne, Wasp, who offers to share her apartment with Jen and then leaves her alone to luxuriate in this fantastic apartment. Jen, delighted, flops onto a giant bean-bag chair/bed, this time, a half-page pic of her flop, another full-figure picture, as we see in the previous illustration.

Don’t return for the second issue of She-Hulk (she’s on the cover again, this time seated on the book title) unless you like full-figure pictures of green women. (Well, who doesn’t? But if it weren’t 3:30 a.m. and I can’t sleep so I may as well write something, I wouldn’t have read and reviewed this sorry specimen of a superhero comicbook—a pin-up book, really.)

QUOTES & MOTS When pondering Time magazine, I never noticed before: Time spelled backwards is Emit, perhaps a better name for a newsmagazine.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. THE GASBAG LEGIONS have been tuning up all year in preparation for Joe Biden’s first year anniversary. And when it arrived, the bloviators expounded accordingly, finding the Biden presidency severely lacking in all sorts of desirable behaviors. Among the most frequently listed of Biden’s so-called “failures” is the “disastrous” withdrawal from Afghanistan, the number of illegal immigrants that streamed across the southern border into the country this year (all because of Biden's refusal to enforce our immigration laws), inflation (principal cause of which is high energy prices—the product of Biden's energy policies), restricting domestic oil and gas production, mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic characterized by frequent policy reversals, failing to abolish student loan debt, not dropping Trump-era sanctions on Iran and re-entering the Iran deal, and failure to take significant action on climate change. All of which overlooks some of his administration’s accomplishments— ending the Afghanistan “War,” greatly minimizing the drone war, ending the Keystone XL pipelline, passing the $1.9 trillion American rescue plan, passing the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill, and raising the pay of federal contractors to $15/hour. And the economy is booming and unemployment is at an all-time low. But presidents can’t much affect these matters—although they are blamed if something goes awry in either realm. But when the GasBags get this far in their assault on Biden, they discover something else to rail on about. Something more deliciously threatening. They’ve discovered that the United States, bastion of liberty and the celebrated home of a model democracy, is becoming more and more authoritarian—more fascist—as time wends onward. Several mobs of Concerned Citizens even claim that democracy in this country is over. It’s disappeared. Gone. Other Concerned Citizens maintain stoutly that democracy isn’t over in this country. Not yet. But it’s leaning in that direction and we must DO SOMETHING to prevent losing it altogether. Among some of the Concerned Citizens the fear that the United States is less of a democracy these days is fairly real. They’re serious about its impending loss. And they’re whipping up enthusiasm—for what? For an overthrow of the government (because it’s a fascist government)? Hard to say what Concerned Citizens are advocating for. But, alas, I’m not concerned. Much. As I said a couple months ago, democracy is best thought of as a game, like any board game in your closet. The game has rules. To play the game, you must follow the rules. When you stop following the rules, the game ceases. It cannot survive without its rules. When democracy slowly expires, there is no violence. The government does not change with a coup. It changes slowly, almost imperceptibly. Until we wake up one day and realize that some of the rules that sustained our democracy are no longer being adhered to. And so democracy ceases. No rules, no democracy. So how do we prevent the loss of democracy? Simple: just follow the rules. (Among the rules are provisions for protesting against the government—the third sentence of the Declaration of Independence, “the right of the people to alter or abolish”— so it’s not as if we become obedient sheep.) Now, to respond to the Concerned Citizens: if we were in real danger of losing our democracy, there would be more wholesale rule flouting. There would be less adherence to the rule of law and of order. People would start driving on the wrong side of the street and going to the head of lines of people who are waiting for the tally of their grocery bill. The Trumpet has been the most conspicuous example of an elected leader who simply avoids obeying the rules. Because of the enthusiasm of his most passionate followers, his growing autocracy seems powerful—and growing more powerful every day. But it isn’t. Despite the reporting of the news media, the Trumpet isn’t all-powerful. His progress towards a fascistic society has been often frustrated. By the Supreme Court. The Supremes have repeatedly ruled against some scheme or another of the Trumpet’s. And as long as the Supremes continue to uphold the rule of law as embodied in its function, the Trumpet will remain what he has always been—a loud mouth who got lucky once. And our democracy will survive. It will frustrate and defeat fascist tendencies. And the Supremes are not alone. Many other Americans feel the same way. And the news media will continue to function as a megaphone loudly voicing its objections to fascism (while at the same time, often egging on the autocrats. Go figure.) Democracy is not in as much trouble as the Concerned Citizens claim. It just makes noises like it is. And it could get that way. Nothing’s guaranteed. But at the moment, those who seek to bypass democracy because it’s so inefficient in favor of fascism because it is so much more efficient will be frustrated by various institutions in our society. Not all of them maybe. But enough. Enough to keep us afloat for a while yet. And how can we help? Easy. Just obey the rules.

TOP TOONS OF THE YEAR YEAR’S END prompts lists of the year’s accomplishments. Ann Telnaes —winner of both the NCS Reuben and the Pulitzer—produces editorial cartoons for the Washington Post, animated cartoons as well as the traditional static commentaries. Her own selection of her own year’s best (mostly in the latter mode) follows:

And then, two of Telnaes’ animated editoons. This being a static medium in front of you, you must imagine motion from the progressive movement depicted in selected moments culled from the animations— static seconds in the over-all motion of each cartoon. Enjoy.

See Opus 149 for more on Telnaes.

DARYL CAGLE operates a syndicate, CagleCartoons.com, that distributes editoons daily to about 700 of the nation’s 1,500 or so daily newspapers. Based upon popularity—how many papers used which cartoons—Cagle published at his website the Top Ten Editoons of 2021. Interestingly, none of the Top Ten used caricatures of politicians. Why not? My guess is that a caricature immediately “selects” the papers that publish it: editors that like that politician, publish the caricature; those that don’t, don’t. It depends, ultimately, upon whether the caricature depicts the politician favorably or not. Readers are likely to be upset if a favorite politician is caricatured. If you don’t publish cartoons with caricatures of politicians in them, you avoid getting your telephone switchboard jammed up with readers calling to protest. Without caricatures, the editoons will be picked and published based upon newspaper editors’ support —or lack thereof— for the issue drawn in the cartoon.

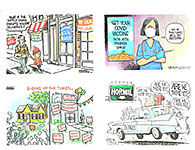

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy AS USUAL, I’VE RUN OFF AT THE MOUTH so much so far this opus that the only way left to reduce the bulk is to abbreviate our coverage of the month’s editorial cartoons. Herewith. (But we’ll do a Special Edition of mostly editoons in a week or so, just to catch you up.) One of the continuing top events of the month concerns the House investigation of the January 6 insurrection. (Or, as it’s known in journalismspeak, Jan6.) Did it happen as a result of the Trumpet’s urging? Or not? No sane observer believes the latter. It was Trump, no question. In

the first cartoon at the upper left, John Cole gives the “6" in

Jan6 a functioning role in a visual metaphor wherein the Grandstanding

Obstructionist Pachyderm’s share of the guilt results in his being hanged by

the 6. Next, Steve Breen gives us his opinion on the Trump-as-instigator question with a visual metaphor of the Trumpet as the conductor of the insurrection orchestra. Then Clay Bennett’s image is of the Trumpet playing one of those electronic television games, labeled “January 6th,” a sure sign that for Trump, the insurrection was a game—a game he activated and controlled. In

the next array of editoons, Mike Thompson’s imagery depicts the

GOPachyderm actively preventing anyone from getting their hands on the “smoking

gun” of January 6 that reveals the GOP involvement. A passerby adds another

dimension with a remark about the Republicon attitude on gun rights. Then John Darkow gets into the discussion about the disappearance of democracy in these United States. The Christmas season always activates the Returns and Exchanges department in the nation’s stores, and Darkow employs imagery that shows the GOP Elephant returning “democracy” because it’s “not for me.” But that’s not Darkow’s final word on the topic. At the lower right, he shows the Statue of Liberty, clutching democracy to her bosom as she crumbles away. Uncle Sam is a little hysterical, and it’s not altogether clear who he is addressing, but the GOPachyderm’s response is a hoot! “We can buff it out.” As if major destruction can be remedied so easily. Next, Andy Marlette’s visual metaphor is a classroom with children saying the Pledge of Allegiance as it is worded in the post-Jan6 days. In

our final display for the abbreviated Editoonery in this opus, we begin with Matt

Wuerker’s reaction to the Jan6 insurrection and kindred abuses. For him,

the Summit for Democracy is seriously flawed by a mob of Trumpists who want to

Stop the Steal of the 2020 Election, the Republicon Pachyderm choking the life

out of the Democrank donkey by gerrymandering, and what is probably a White

Supremacy torchlight parade in the distance. Uncle Sam looks more than a little

hesitant about letting in a bunch of immigrants. Then Dana Summers creates an image of the Ukraine crisis in which Putin asks the question that all of us know the answer to—given the clue provided by the tanks. For Bob Gorrell, Prez Biden’s response to the Ukraine situation is not a strong warning to Putin to stand off: the line Biden draws isn’t clear. Finally, with the Olympics all around us at last, John Darkow has some fun with his own version of some other kinds of winter events. And that’ll do for the nonce. We’ll be back in a trice with a much more generous sampling of editoonery over the last 30-40 days.

READ & RELISH Here at the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wurlitzer we collect t-shirt witticisms, to wit—: I have reached the age where all I exercise is caution. I’m not bald: I’m just taller than my hair. If you just did what you’re told, I wouldn’t have to be so bossy. I’ll worry about getting old when I stop looking so damn sexy! I don’t want to brag or anything, but I can still fit into the earrings I wore in high school.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words AT VARIOUS TIMES during the reign of the Trumpet, Time magazine did a series of cover portraits of him seated at the Presidential Desk while being progressively overwhelmed with flood-like waters. A couple weeks ago, Time started the same sort of thing with Biden, as you can plainly tell from the accompanying illustrations. (The pictures, by the way, are not exactly in chronological order in each of the two illustrations. In fact, in each one, they go in reverse, left to right.)

I recently renewed my subscription to The Washington Examiner, a brazen absolutely unrelenting right-ward leaning—nay, stampeding—publication. And the subscription ain’t cheap. But I renewed because I like the caricatures it often prints on the cover—and usually, inside. Nearby is one of the cover caricatures of Biden sitting in chair too big for him; to that, I’ve added Tom Bachtell’s Biden, mine, and a photo of the Prez smiling. (Alas, I failed to make note of the cartoonist who did the big chair cover portrait; maybe next time.)

NEXT, IN THE SPIRIT of this picture section—but without neglecting altogether the informing function of Rancid Raves —we have three pictures of nearly naked wimmin. These were all clipped from the last couple issues of Previews, the Diamond catalog of coming comics attractions. We post them here in the never-neglected role of relating the news. In this case, the news is that Previews publishes, amid its listing of coming comicbooks, pictures of nearly naked wimmin.

Yes, as they used to say in newspaper headlines, “Comicbooks Aren’t for Kids Anymore.” I wonder if Mama and Papa know what their kids are seeing in the comicbooks they’re reading. H’mmm?

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS A nation of sheep will get a government of wolves.—Edward R. Murrow

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—:

All of the Marvels By Douglas Wolk 368 6x9-inch pages, mostly text, some illustration; 2021 Penguin Press hardcover, $28 WOLK RESORTS, sometimes, to notions more elaborate than necessary; f’instance: “Then Kirby, Lee, Ditko and their collaborators figured out how to make the individual narrative melodies of all their comics harmonize with one another, turning each episode into a component of a gigantic epic.” He means that they started continuing stories from one issue to the next, and they also put all their heroes into the same U.S. cities where they might, and sometimes did, meet each other and work together. From this, Wolk concludes that all of the Marvel comicbook stories effectively make up one long epic tale. And when we realize that Marvel has been publishing comicbooks under the Marvel banner for more than six decades, we can take the next step, as Wolk does, to see Marvel comics in the aggregate as the longest single work of fiction in the history of works of fiction. This discovery, despite the sometimes pretentious language, is an intriguing one. And the question—what does it all mean then?—likewise. Wolk read all 27,000-plus issues of Marvel comics looking for an answer. “I didn’t read them in order, of course,” he says, “... I grazed. ... And how did I read them? Any way I could. I read them on couches, in cafes, on treadmills. I read them as yellowing issues I’d bought when they were first published. ... I read them as bagged and boarded gems. ..And I had an absolutely great time.” The volume at hand is Wolk’s attempt to formulate an answer—to come to a conclusion about what it all means by surveying the content of all of Marvel comics. All of them. En route to an answer, he answered some questions—like: If I like character, so I have to read everything they’re in to understand what’s going on with them? “No,” he says, —no more than you have to follow your friends around 24/7 to understand what’s going on with them.” He also observed that superhero comics have been “political” from the beginning. The cover of the first issue of Captain American shows Cap striking Hitler on the face—“which is to say that Joe Simon and Jack Kirby created Captain America specifically as an argument for the U.S. to enter the Second World War.” Interesting. But how about Superman’s krypton origin? Political? I don’t know how Wolk answers that one. (I haven’t read the whole book, kimo sabe: the function of this department is to inspect a book in much the way that you would while standing in a bookshop, flipping pages in a volume to determine what it’s about and whether to buy it. You don’t read it.) But as I was pondering whether the creation of Superman was political, I came across Jules Feiffer’s answer to the question. And it’s intriguing enough to quote here, almost all of it—: “Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster [the creators of Superman] were two Jewish boys from Cleveland at the height of American anti-semitism and the rise of Hitler in Europe, and they, like all nice Jewish boys, wanted to assimilate—they just didn’t want to be Jewish but American.” They saw the “American dream” in the movies, a dream “that was actually an America invented by Jewish producers.” They envied the jocks in high school who got all the girls—“all the Lois Lanes—and they didn’t. “So Superman became a fantasy of assimilation. If only Lois Lane knew my true identity. If I rip off my clothes, I reveal I’m not only this schmuck Clark Kent, with glasses and a bad complexion; I’m really—zoom—Superman, stronger than those other jocks.” So that’s the politics of the creation of Superman. In attempting to determine what this Marvel “story” “means,” Wolk says: “The story’s shape emerges from its cross talk and disarray like constellations from the stars”—an excellent metaphor for what he is doing. Summarizing at the end of the book, Wolk says: “The contours of the story often resemble the contours of the cultural environment and moment in which it was produced, in a broad and distorted way, in part because it’s made up of the work of so many distinct, individual voices trying to create something that would be entertaining and meaningful to their audience (and to themselves) in that moment.” Wolk sees what he calls “the Marvel story” as divided into six parts, each tied to a time period: 1. 1961 - 1968: The story reflects huge technological invention and fear of Communism 2. 1968 - 1980: Political turbulence, collapse of the established order, emergence of “evil” archetypes in the wake of the Watergate scandal 3. 1981 - 1989: An era of malign forces, systemic oppression at home and powerful villains. The mutant metaphor of the X-Men made their books the best-selling American comicbooks during this period. 4. 1990 - 2004: Antagonists are internal —perhaps a reflection of Watergate; security vs. privacy debate 5. 2005 - 2015: Utopians are the villains, but the universe ends 6. 2015 - : Heirs and inheritances Through it all, given the mission of superheroes, is the struggle between Good and Evil. It goes on forever, always. And Good, while not always triumphant, is always persistent. That is “the Marvel Story.” The book’s penultimate chapter, the chapter before “Passing It Along,” is entitled “Good Is a Thing You Do.” To say that Wolk’s work is impressive is to understate his achievement by several light years. After the first chapter’s somewhat overblown lingo, he gets down to business and writes as we all speak about superheroes and comics. To the extent that Wolk achieves his objective in writing this book—and I assume he does—his grasp of the stories and their innumerable facets is beyond impressive. It’s god-like.

The Life and Comics of Howard Cruse By Andrew J. Kunka 194 6x9-inch pages, b/w (2 pages in color); 2022 Rutgers University Press paperback, $29.95 IF YOU’RE LOOKING FOR a serious treatment of Cruse’s cartooning career, this is the book for you. From the Rutgers write-up: “This book tells the remarkable story of how a preacher’s kid from Birmingham, Alabama became the so-called ‘Godfather of Gay Comics.’ Lavishly illustrated with a broad selection of comics from Cruse’s fifty-year career, this study showcases his critical role as a satirist and commentator on his times.” And as editor of Gay Comix, Cruse influenced the development of gay comics and of the community of gay cartoonists. On the back cover, one quote says: “I’ve been waiting a lifetime for this book!” Karen Green, curator for Comics and Cartoons, Columbia University Libraries, writes: “A much-needed critical biography that makes clear exactly how courageous and groundbreaking Howard Cruse had been, in both his comics and his eloquent, impassioned activism. ... [D]etails Cruse’s influence on emerging and future generations of queer cartoonists.” Kunka begins with a short (40 pages) “critical biography” and then examines and analyzes many of Cruse’s shorter works (1, 2, 4—the longest is 7 pages) in chapters the titles of which suggest the range of the remainder of the book: Autobiographical Fiction/Fictional Autobiography, Commentary and Satire, Parodies. The

analysis is detailed and helpfully supported by sample pages (or, more often,

the entire work) of the comic being considered. And here, I run into my only

criticism of the volume: the illustrations are too small. They verge on

minuscule. Yes, you can read them, but you might need the help of a good

magnifying glass. Cruse’s

longer works—Wendel, Stuck Rubber Baby—are often mentioned but are not

given the kind of detailed treatment the shorter works receive. I’m

disappointed that Cruse’s Barefootz strip, very early in his career,

doesn’t get more detailed examination, but I suspect that Kunka regards this

effort as thoroughly conventional (“proscenium” design, “two-shot”

conversations) Barefootz ran for nearly ten years (the 1970s) and was a staple in Cruse’s professional life; surely it deserves more than Kunka gives it. Perhaps I’m only pouting because Barefootz is one of my all-time favorite comic strips. Still, Kunka does allow that “Barefootz evolved from a gag strip to ‘an extended allegory populated by a repertory troupe of players perfectly tailored for social and political satire, observations about personal relationships, and explorations of the very nature of reality’” as Cruse put it later. All of which you can get out of a tribe of cockroaches living in your apartment. The book lacks one thing that Kunka planned for—a long conversation with Cruse. Alas, the cartoonist died before they could conduct the interview—of cancer, on November 26, 2019.

Tom the Dancing Bug Without the Bad Ones By Ruben Bolling 144 6x8-inch pages, color; 2021 Clover Press paperback, $15.99 THE COVER proclaims that the book’s selection is from 1990-2021, and it reprints Tom Bug’s comic strip parodies in their original full-page format, albeit at a somewhat smaller dimension. About a third of the strips—those at the front—are in black-and-white, which implies that these are the oldest. Bolling’s parodies assume their customary forms: most of them are the Donald and John strips, but others starring the usual culprits are present— Lucky Ducky, Hollingsworth Hound, Aunt Man, Chargrin Falls, Harvey Richards, Definitely-Not-Gay-Man, and God-Man. Also present are two pages of the Q-Nuts strips for which Bolling deploys his parody of Peanuts. It’s funny and apt enough, but Charles Schulz has done all the heavy lifting; all Bolling has to do is step into the shoes of Charlie Brown and Linus, and most of the comedic work has already been done. In effect, when he uses Q-Nuts, he’s cheating just a little by relying upon someone else’s work. At least two other volumes of Tom reprints are available, the sixth and seventh of a series that the volume at hand is not a part of.

HERE’S A MISTAKE not to make. Don’t buy the Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips graphic novel Cruel Summer if you already own the twelve issues of their Criminal comicbook wherein Teeg Lawless dies in the last issue. (Spoiler alert not necessary: at the end of the first issue, a caption tells us that “by the end of the summer, he’d be dead, his brains splattered across a wall.”) The two publications are the same despite the different title (Cruel Summer) on the bound-together book. That’s right: they changed the title for the bound-together re-issue. There oughta be a law against that. When someone binds issues of a comicbook together in one publication, that publication ought to have the same name as the individual issues have. Not only did I in effect buy Criminal twice, the second time as Cruel Summer, but I noticed that my stack of Criminal comicbooks (which I hadn’t yet read) was missing Number One, so I went out and bought it (even though it was terribly expensive). It’s probably Image’s fault that the bound-together re-issue has a different title than the first printing of Criminal. Brubaker and Phillips are terrific storytellers, no question. But if I want to read something a second time, I don’t need a second copy of the same book. Phillips produced a spectacular cover for Cruel Summer. Inside, he lays on the blacks, even obscuring huge tracks of a character’s face. Unless the character is a good-looking female. Then, magically, no black shadows on the face. Take a look.

PERSIFLAGE & BADINAGE Tom Tomorrow of This Modern World fame is the pen name of Dan Perkins. And he’s not sure he likes it. “It happens! That’s what I get for coming up with a pen name. When I was starting out, I was in San Francisco, running a little anti-corporate ’zine called Processed World. A lot of the contributors used pen names because there was always a sense that you might get blacklisted or boycotted or something if you were associated with it. So I started using this pen name, which was a misremembered version of an old cartoon character. I didn’t quite realize that I was going to have this 25-year career and would be stuck with this thing!” Upon reflection, he realizes that his pen name isn’t such a bad thing. “I thought it would be a mnemonic device. The cartoon wasn’t about politics so much in those days; it was riffing on technology and consumerism, and ‘Tome Tomorrow’ seemed appropriate to this kind of retro-futurist thing I was doing.”

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets The Complete Peanuts: Comics and Stories, 1950 - 2000 By Charles M. Schulz; Edited by Gary Groth 344 6.5x8-inch landscape pages, b/w; 2016 Fantagraphics hardcover, $29.99 WHEN I REACHED THE END of the 25th volume in this series, I thought the reprint project was finished. After all, in that volume we have the strip bidding Peanuts readers farewell, and then, to fill out the volume, the panel cartoon Li’l Folks that ran from June 22, 1947 to January 22, 1950. So that’s all, right? Wrong, and the book at hand will prove it. Herein, we have Schulz’s “extracurricular” work: all 17 of the Schulz single-panel cartoons published by the Saturday Evening Post but never reprinted, all of them, at once before. The only requirement for selection—it must be pictures of Peanuts characters by Schulz; none of his assistants’ work qualifies.

The storybooks were all Snoopy: Snoopy and the Red Baron, Snoopy and the Sopwith Camel, Snoopy and “It Was a Dark and Stormy Night,” and It Was a Dark and Stormy Night. He did advertising art for Ford and for Butternut Bread; he did Christmas strips and cards, and four books under the general heading of Things I Learned After It Was Too Late (And Other Minor Truths), plus Golf cartoons and strips for Bing Crosby Pro-Am tournament, tennis, and more. The best part of the book—apart from these rare renderings of the Peanuts characters (lots of Snoopy)—is the concluding essay by Jean Schulz, Sparky’s widow. They met at the ice arena that Schulz (whose friends called him Sparky) built in Santa Rosa, to which Jeannie was hauling her daughter and a friend for skating lessons, and one day, Schulz, who’d noticed her, asked her name. “My name is Jeannie,” she said, and “the simplicity of my answer encouraged him to ask me to sit down with him and have a cup of coffee. A little over a year later, we were married.” Schulz wrote a poem about their meeting, the concluding verse of which is—: You hurried by and caught my eye And love joined us forever. “Sparky was proud of the simplest things I did, but he also recognized when I was in over my head, and he was there to help,” says Jeannie, who was involved in a number of “projects”—public service efforts and the like. Sports were a part of their lives together from the start—Sparky with golf, tennis for both, and, three times a week after work, running, during which they discussed their days. “It was a simple routine that suited us well. When we got home to dinner and teenage children, we had already had a good catch-up time together.” Jeannie’s essay is full of anecdotes about her famous husband’s various routines and the pranks he often played. “Sparky was a great observer of people. ... As an artist, he was always observing his environment. He said frequently that when sitting in a meeting he was always ‘drawing with [his] eyes,’ noticing the fold of a shirt next to the collar and the drape of a curtain.” In conversation, Sparky always stimulated the discussion by asking questions, often unexpected: “How did your parents meet?” “Sparky worked hard to keep his life simple,” Jeannie writes. “Although he was proud of the recognition and honors he received, he never made more of them then they were. He was fortunate that his greatest joy was sitting at the drawing board feeling the pen nib pass over the paper as he executed his comic strip.” Elsewere, she says: “By the time we were married, Sparky was thoroughly professional. The comic strip seemed to flow smoothly from him like water from a pitcher. ... I recognized his genius, but on a day-to-day basis, I took it all for granted.”

IRKS & CROTCHETS She was only a fireman’s daughter, but she sure did go to blazes. She was only a surgeon’s daughter, but oh, what a cut-up. She was only a professor’s daughter, but she learned her lesson. She was only a moonshiner’s daughter, but I loved her still.

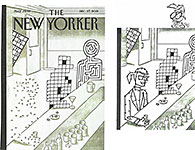

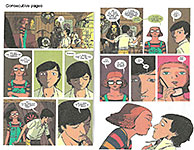

BOTTOM LINERS Single Panel Magazine Cartooning THE DECEMBER 27th ISSUE of The New Yorker is the magazine’s "Christmas Issue.” Even though it’s dated post-Christmas, it was published long enough in advance of Christmas to be on the newsstands for a week before the holiday actually descended. This issue is dubbed the "Cartoons and Puzzles" issue. Sadly, it fails conspicuously on the “cartoons” part. The puzzle is how the editors could have persuaded themselves that they’d succeeded. Despite being the nation's foremost publisher of single-panel cartoons, the magazine can't seem to produce an issue in homage to that medium. And the editors seem to have secretly realized this in advance of publication, so they’ve commandeered puzzles, adding them to the line-up in the hopes that something worthy of this historic magazine will surface. Alas, it hasn’t. In this issue, for example—the “cartoons” issue, remember— they've violated a long-standing tradition of the magazine and published a comic strip, not a panel cartoon. They’ve done that before, and it’s no sin. Emma Allen, The New Yorker’s cartoon editor, told us a long time ago that among her favorite forms of cartooning is the multi-panel form, so we shouldn’t be surprised. But we are. We could not have imagined the atrocity that unfolds before us. It’s no simple comic strip: it runs on for 10 full pages. Ten! It’s more of a comicbook than a comic strip. And those 10 pages display the most atrocious black-and-white rendering (in both senses) that can be perpetrated. There is nothing even remotely resembling artistic achievement on these pages. It soils the pages of the magazine. All 10 pages are committed (I can’t say “drawn”) by Liana Finck, one of the magazine’s regular so-called cartoonists who has failed at Drawing 101. The comic strip tells a mutilated version of the story of Noah and his ark. We’ve reproduced four of the ten pages near here. The first three pages are consecutive from the first page. The fourth page is close to the end of the story. I pulled it out because it contains the only funny parts of the story: it shows Noah working at an unusual sacrificial altar and then explains why there are no unicorns.

In addition to the comic strip, the “cartoons issue” prints 16 panel cartoons. These, as always, evoke cartoon editor Emma Allen’s so-called sense of humor, which delights in nonsequitur comedy—comedy arising from juxtaposing two wholly otherwise unrelated ideas. Nonsequitur humor is silliness. Surprisingly, of the 16 cartoons, four are not silly: they are, in fact, humor of the kind that comments upon some aspect of ordinary life (or reveals something about daily life that we’d otherwise overlooked). We’ve reproduced 4 of the 16 cartoons hereabouts. One of them, the one at the lower right-hand corner, is virtually an analysis of Emma Allen’s sense of humor. Two of the remaining three are in the more-or-less traditional social commentary mode of panel cartoons; the fourth, at the lower left, is another Emma Allen specimen. “These gags about the holiday season are best enjoyed in front of a roaring fire, with a hotbeverage in hand. (But hunched over on the subway is fine, too.)” In addition to the 16 gag cartoons, we are treated to a full-page George Booth cartoon (thank heavens for that!), a full-page new year’s festivity diagram by Roz Chast, and a two-thirds page vertical strip by E. Flake (which we’ll reproduce at the end of this scroll).

THE COVER of

this “Cartoons and Puzzles” issue is devoted to a couple puzzles. One of which

is a "connect the dots" game. So, playing along (for a change), I

connected the dots. Imagine my surprise when the picture that emerged was of a

flop-eared personage—even wearing glasses! A giant-size version of my rabbit,

who is inspecting the artwork from above. Incredible. Inside are other puzzles, one of which is a two-page spread of a cartoonish drawing depicting a street scene. We are invited to find in this confused milieu Eustace Tilley, the magazine’s mascot, and the butterfly he is usually inspecting through his monocle. The solution is depicted later in the magazine with the answers to all the other puzzles. I’m not a puzzle fanaddict, so I dare not vouch for how expert the puzzles in this issue may be. But if the cartoon content’s birsmirching of that medium is any indication, I suspect the puzzles are lousy—either impossible to solve or too easy. Finally, in the book review section, we see a one-paragraph review of Douglas Wolk’s All of the Marvels. The reviewer seems to like it but he describes rather than evaluates.

Another Anniversary

And when the magazine approached its first anniversary a year later in 1926, no one—not Irvin, not Harold Ross (the founding editor), not anyone now long forgotten—could think of a cover image to celebrate the occasion. So they used Irvin’s cover picture again. And the ritual was repeated for the next six decades until Tina Brown became editor of The New Yorker. Eventually, come 1994, she had to confront the anniversary problem that no one had overcome in the magazine’s 69-year-old tradition. And her solution was startling in its novelty at the old hide-bound periodical. She

abandoned Eustace Tilley in favor of another image, a 20th century version of

the boulevardier— a chronic slacker and layabout drawn by Robert Crumb,

who depicted a slovenly baseball-cap-on-backwards youth in the time-honored

posture of Tilley, but instead of a butterfly, this lout was looking at an

advertisement for an adult movie theater. You would have thought the Virgin Mary had lost her virginity to Donald Trumpet. That’s the volume of outcry Crumb’s “Tilley” caused. (It was subsequently christened Elvis Tilley.) Next year, they went back to the traditional Ivin cover. But the surrender to tradition didn’t last long. Having broken the mold, a couple years later, The New Yorker abandoned Eustace Tilley again in favor of some more contemporary image that conveyed a timely message but assumed the Tilley posture. After

that, the anniversary cover was unpredictable. Sometimes it was the standard

Eustace Tilley again; sometimes, not. This year is another of the “not” years. In reviewing this ancient history one February years ago, I observed that the only thing that remained constant in the changing images of the anniversary cover was the butterfly. And this year, even moreso. The

personage in the picture appears to be an African. He/she is wearing a robe

with butterfly images all over it. And there’s an actual, lonely solitary

butterfly perched on his/her shoulder. The meaning of this image evades me. And its title, “High Style,” offers no clue. But I like it anyhow. Surrounding

the butterflied African is an array of Eustace Tilley pictures in which he

celebrates his anniversary—small spot drawings by Luci Gutierrez; they

are scattered Tilley appears at a larger scale—a two-thirds page vertical strip of panels— early in this issue where he joins in the anniversary festivities by inspecting the butterfly at great length; after which, he seems to be taking a selfie. And next to him and the butterfly, we’ve posted the Emily Flake multi-panel cartoon that we mentioned when we started on this journey.

TICS & TROPES When you work here, you can name your own salary. I named mine: “Jeff’s.” A fool and his money can throw one hell of a party. When blondes have more fun, do they know it? Learn from your parents’ mistake. Use birth control. Money isn’t everything. But it sure keeps the kids in touch. Don’t drink and drive. You might hit a bump and spill something.

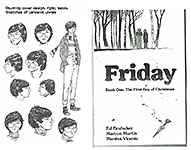

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status