|

|||||||

Opus 418 (through May 22, 2021). Happy Anniversary! Yes, it’s happening again this year. With the last posting in May—this one— we complete our 22nd year of Rancid Raves. For 22 years, regularly every other week, we’ve been sending you (and I mean you, John) another posting of comics news and reviews, cartooning history and lore—without fail (or nearly so). To commemorate this occasion, we’ve included in Opus 418, a rare piece of cartoon art—something that can be seen only in comics/cartooning. AND— And for this opus, we offer Open Access, which means that even non-$ubscribers can enjoy the entire opus. And more. We review last month’s editoons, listen to R. Crumb on women, art and Trump and review the long career of M. Thomas Inge, who virtually created the academic, scholarly treatment of cartooning and comics. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order (the longest entries are marked with an asterisk* a reader’s guide to help you decide where to spend your time)—:

NOUS R US Kelley and DeAdder Win Awards Crumb On Women, Art, and Trump

Bottom Liners Single Panel Magazine Cartooning

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy **Almost 90 Editoons From the Last 40 Days More Cover Editoonery Front Page Duffy

Rancid Raves Gallery Happy Anniversary— Rare and Only in Cartooning Comics My Beer

PASSIN’ THROUGH *M. Thomas Inge David Anthony Kraft

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND—

“If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

KELLEY AND deADDER WIN AWARDS Steve Kelley, who editoons at the Post-Gazette in Pittsburgh, won the National Headliner Award for editorial cartooning. Judges’ comments reported by D.D. Degg: “Steve Kelley doesn’t play in cliches. His cartoons stood out for their originality, smarts and focus on the hilarious moments that were so very hard to find in 2020 – some on the national stage, and some in our own homes. His artistic hand is crisp and clear, and his messages go right to the gut — causing a laugh, a headshake or a glance at the calendar: Is it 2021 yet?” The

National Headliner Awards were founded in 1934 by the Press Club of Atlantic

City to honor the best journalism in the U.S. The annual contest is one of the

oldest and largest in the country that recognizes journalistic merit in the Second Place in this year’s competition went to Clay Bennett at the Chattanooga Times Free Press; Third Place, to Mike Smith of the Las Vegas Sun – Greenspun Media Group. In Canada, Michael de Adder is the winner of the Editorial Cartooning category in the National Newspaper Awards. DeAdder, interviewed by the CBC about cartooning today’s Canada and cartooning post-Trump, said the world is tired of hearing about former U.S. president, even in the form of cartoons lampooning him. “They would like forget about him. Trump’s not going to allow that, but they would like to forget about it,” de Adder said.

CRUMB ON WOMEN, ART AND TRUMP R. Crumb was interviewed at theguardian.com by Nadja Sayej in March 2019, prompted by an gallery exhibition of his work. Among other things, Crumb talks about how his feelings on Trump have changed and why he has stopped drawing women. It’s a marked difference from a time when his work was typified by thick-thighed pin-up women. Even in his 2016 series “Art & Beauty,” he featured a bathroom mirror selfie of a 21-year-old model who voluntarily emailed him nudes. “I don’t even look at women any more,” said Crumb in the interview he gave while in New York for the exhibit. “I try not to even think about women any more. It helps that I’m now 75 years old and am no longer a slave to a raging libido. “When I was young,” he went on, “I was just obsessed with sexual desire, fantasizing about sex, masturbation, trying to figure out how to get laid. It was awful. Fortunately for me, I found a way to express this inner turbulence in my comics, otherwise I might’ve ended up in jail or in a mental institution. No exaggeration. I’m better now. I worked it all out somehow. Success and the love of real women helped me a lot. Aline really saved my dismal ass.” He’s referring to Aline Kominsky-Crumb, his wife of 41 years, a cartoonist in her own right [despite terrible drawing ability—RCH] and sometime collaborator with her husband. But not everything has changed since 1967's Summer of Love. While pointing out the pretty portraits of his wife, Crumb reveals his other lovers, too. “There are a lot of drawings in this show of other women I’ve been involved with intimately, both before and during my relationship with Aline,” said Crumb. “We have a kind of ‘open marriage,’ bohemian artists and libertines that we are.” This

exhibition, curated by Robert Storr, focuses on Crumb’s sketchbooks from the

1970s. There are drawings of acrobatic women with Kardashian-sized rear ends, sleazy

businessmen smiling behind cigars and one sketch of a rabbit man slapping a

woman across the face. Another has a woman with the words “Sex Object” floating

above her head. When asked to elaborate, Crumb doesn’t recall drawing it. “I’m sure I must’ve used the term ironically, a sort of self-accusation,” he ponders. “Yes, I’m guilty of looking at women as ‘sex objects,’ I’ve done it thousands of times over the course of my life. I could not help it. The sight of a woman with a large ass and strong legs instantly electrified me. It was not something I could stop myself from feeling. I could only stop myself from acting on it, and therein lies Freud’s Civilizations and its Discontents.” Crumb’s superwoman-esque drawings were not always meant to empower. “When I was young, I had a lot of anger towards women, as well as towards men and toward human society in general,” he says. “I vented my feelings in my artwork, in my comics. I was crazy enough not to think about the consequences too much.” But things changed when Crumb began being criticized. “I became more self-conscious and inhibited,” he said. “Finally, it became nearly impossible to draw anything that might be offensive to someone out there, and that’s where I’m at today. “So yeah, I don’t draw much any more,” he said. “It’s all right. A lot of ink has gone under the bridge. It’s enough.” For decades, Crumb carried a sketchbook with him everywhere he went, something he learned from Leonardo da Vinci (even though they aren’t contemporaries). It was the 1970s, a time when he drew religiously. “I drew from life, from photos and from my imagination,” said Crumb. “I also used them as diaries, filling many pages just with text; long rambling self-reflections. I was socially alienated and had a lot of time on my hands.” Also on display in the exhibition is artwork from issues of HUP, a self-proclaimed “comic for modern guys”, including one issue from 1989 where he flushes Trump down the toilet after reading Trump’s book, Art of the Deal, which Crumb found offensive. “My opinion of Donald Trump has changed a bit since I did that strip about him in 1989,” said Crumb. “Back then, I think I gave him a little too much credit for possessing a bit of class and sophistication. I now have a lower opinion of him than I did then. I now perceive a certain low, thuggish quality in his character, a guy who can say with a totally straight face: ‘Where’s my fuckin’ money? I want my fuckin’ money!’ It’s a quote from Bob Woodward’s book Fear.”

When asked if he feels misunderstood, he said only if his audience thinks he believes everything he draws. “I only feel ‘misunderstood’ when people react to my work as if I were advocating the things I drew; the crazy, violent sex images, the racist images,” he said. “I think they’re not getting it. I did not draw those images with the intention to hurt anyone or insult anyone, with the exception of the very few times I did strips making fun of specific individuals, like Donald Trump.” Crumb suggests it’s up to the audience to decide. “I’m just a crazy artist. I can’t be held to account for what I draw,” he said. “Personally, I don’t think they had a bad influence on people. I don’t think it works that way. Conning people, deceiving people, that is what is harmful to them.”

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing The best resource I have about the state of the editorial cartooning profession is that there are only 30 full-time staff political cartoonists left. There are maybe half-a-dozen more who are syndicated (not on staff) or are contracted to produce editorial cartoons for a particular publication or are freelancing. But those bring the total to only about 40. It was 100 in 2008, just 13 years ago, kimo sabe.

BOTTOM LINERS Single Panel Magazine Cartooning OVER THE YEARS, I’ve clipped and filed hundreds of gag cartoons. Just about any time I see one that is unusual or just weird, I clip it. This posting’s harvest appears here, in two installments. There’s not much to say about these cartoons. They all blend words and pictures to achieve a comedic meaning neither attains alone without the other. They are perfect demonstrations of my theory of good cartooning. The Bizarro cartoon at the lower left is worth a comment. This joke is

possible only in cartooning. Only in a cartoon can “guys” be made into “guise,”

which is the basis for this joke. But you must SEE the spelling

of “guise” to get the joke. If you don’t see it—if, for instance, you HEAR the joke—there is no joke because “guys” and “guise” sound exactly the same.

Here, the picture (of the guise) completes the meaning of this play on words. The next display has two of my favorite cartoonists in it—both at the right-hand extreme, Bob Vojtko and the late Randy Glasbergen. Vojtko’s distinctive styling is a treat for the eye and the funnybone. The woman in this cartoon is thoroughly ordinary; but the man, with his remaining hair stuck on the back and his eyes wandering across his face—he’s a joke in and of himself. Glasbergen

is the nose champion in cartooning. His noses dominate any Glasbergen cartoon—another

delight for the eye. The Bizarro cartoon in the middle of the lower line-up brings up a subject I’ve often toyed with in my mind. I imagine the first guy to realize how a growing domestic population comes about: he smacks himself on the forehead suddenly and exclaims, “So THAT’S how it’s done!” This guy, however, obviously comes along several ignorant generations after Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. We’re sprinkling displays of a few more gag cartoons through the ensuing Editoonery section—just to break up the monotony of pondering serious political issues one cartoon after another all day long. A few bottom liners to give us all a break. Onward—:

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE MOST RECENT newsworthy events that have attracted editoon attention are: 1) the outbreak of aerial bombardment in Israel and the Gaza Strip and 2) the humiliation of Liz Chaney in the House of Representatives. Chaney suffered the consequences of audibly declining to believe the Trumpet’s Big Lie—that the election was rigged and his victory stolen from him. And now we know why every good Republicon supports Trump: if they don’t, they risk getting destroyed by his backroom machinations. Chaney is an object lesson for her fellow Republicons. She is consistently conservative, as NationalReview.com said in an editorial. She voted with Trump on substantive issues 93 percent of the time, compared with 78 percent for Elise Stefanik, Chaney’s replacement in the House leadership. But Chaney would not endorse the Big Lie. So she had to go. One of the reasons The Week is a valuable news magazine is that its cover is usually a political cartoon. (And inside, it devotes at least a page to reprinting editoons from around the nation; sometimes, two pages.) F. Harper’s editoon cover for The Week for May 14 shows Trump and his relationship to the Big Lie, depicting the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderms bent over in absolute obeisance to the man whose political future is founded upon a monstrous falsehood. The elephants’ posture shows them making asses of themselves, but I doubt that means Harper thinks they’ve all become Democrants, donkeys of another sort altogether. At

the immediate right, Dave Whamond’s imagery reveals the nature of Liz

Chaney’s defeat: her truth was not enough to overcome the Big Lie, which,

thanks to the positioning of the fat elephant, is the foundation upon which the

Pachyderm rests, blowing his trumpet. Chaney’s principles defeated her. Nate Beeler, at the lower right, conjures an image that shows the place of principles in the GOP. The Party’s Big Tent under Trump is minuscule, as we can see, and entrance is restricted: “You must be THIS principled to enter” the sign says. The image recalls the height limitation imposed upon some places. Here, your principles don’t have to be very high. Almost no height at all, and you can get in. On

the next display, Scott Stantis’s visual metaphor is the Biblical

worship of a golden calf, which, upon inspection, looks like Trump. The only

one not worshiping is approaching like Moses with the Ten Commandments—or,

“Principles.” He, however, is labeled a heretic by the Next, in Daryl Cagle’s picture of the GOP elephant’s belief, Liz Chaney shows up as something nasty the Pachyderm must’ve stepped in. Then Nick Anderson offers a picture of Chaney blotted out of existence with stamped x’s applied by one of the elephants. The situation represents the GOP’s hypocrisy: it opposes the cancel culture that the politically correct Democranks have imposed lately, but it has no hesitancy in canceling Chaney.

THE SITUATION in the Middle East is by no means as comical as the antics of the GOPachyderm. They’re at it again: bombing the hell out of each other. In Michael Ramirez’s view, the current round of hostilities was launched by Hamas, the militant Palestinian group that controls Gaza: thus, his editoon accuses Hamas of killing the dove of Peace. Hamas, with his toothy grin and tiny, beady eyes is the supreme example of thuggish evil. In the U.S., Israel is routinely portrayed as the innocent victim of Palestinian aggression, to which Israel must (and should) react in kind. That’s what we’re taught to believe by the news media. True to form, Biden commented that Israel had a right “to defend itself.” But

that merely reveals the inherent bias of American news media. And in the

current circumstance, it would appear that the news media in this country got

it wrong. According to Aspen Pflughoeft at Deseret News, it was Israel that started it this time. Israeli courts threatened to evict dozens of Palestinian families in the Shiekh Jarrah neighborhood in order to give Jewish settlers the land. That, of course, made the Palestinians angry, and Hamas stepped up to help weaponize their anger. Hamas was reacting to Israeli provocation. While that hostility was brewing over the weekend, May 8-9, Israeli police raided the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, the third holiest site in Islam as well as the holiest site in Judaism. The Israelis used tear gas, stun grenades, and rubber bullets on Palestinians in and around the mosque. Many of the Palestinians were praying at the mosque; this is the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Palestinians responded by throwing stones and chairs. Next, Hamas in Gaza began airstrikes on Israel with the Israeli mililtary quickly returning fire. In the next editoon in our array, Rob Rogers accurately reflects the actual situation with Israel provoking the Palestinians by creating new settlements of Israelis. Below that, Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher deploys the endless curving Mobius Strip to show that the cycle of revenge, which prompts almost all the violences in the Middle East, is endless.. At the lower left, Dave Granlund’s image of the coming of the new but probably disappointing year—as “a light at the end of the tunnel”— can also serve as a reminder of the deceptive nature of the hostilities in Israel: with every fresh cease fire, we think the war is over and peace will prevail. But that’s just the interval between pipelines.

ANOTHER

MATTER that has consumed the attention of the news media is Joe Biden’s performance

in the first months after taking office. In the next display, Robert

Ariail’s visual metaphor of an overworked housewife captures the essence of

Biden’s situation. The American public in recent polls gives Biden high marks: 60% of those polled say they approve of his handling of the presidency. In tackling the tasks before him, Biden has moved fast, producing detailed legislative packages for Congress to act upon. He’s acted quickly and effectively to get the country vaccinated and to persuade a divided Congress to adopt his Covid relief package and to set forth his massive infrastructure bill. Biden has also taken steps to undo the damage Trump did to efforts to achieve climate control. He’s also started to re-instate the nuclear deal with Iran and to meet the China challenge forcefully (although in both cases, not as successfully, yet, as in other situations). He hasn’t done as well with immigration, particularly along our southern border, with defense spending and with nuclear issues. Pundits (among them, Jessica T. Mathews in The New York Review of Books, May 27) generally approve. Apart from a couple stumbles with Iran and China, Biden “has shown himself to be decisive, bold, willing to take big risks, and politically deft. ... He has assembled a team of experienced professionals whom he trusts and who work well together, although he has been slow to fill the hundreds of national security positions that require Senate confirmation. ... “The pace of policymaking, by contrast, has been extremely rapid and, by and large, sound. ... [Misjudgements in a few areas] stand out against a sweep of good beginnings. They reveal a president in command of both the big picture and the tactical details of foreign affairs. ...” In short, the kind of president that Matt Davies depicts busily cleaning up the image of the U.S. as a world leader. Drew Sheneman’s imagery also shows a Biden that’s knowledgeable and tough, gearing up a gigantic machine to spend what it takes to revive infrastructure and telling Corporations, “Free ride’s over, pal. Get out and push,” signaling that Corporate America must do its share. Gary Varvel takes a decidedly different tack: his visual metaphor has business rendered immobile by a corporate tax hike. We hear this complaint whenever corporations are about to be taxed. Businesses will fire workers in order to reduce expenses and thereby to secure their profit, the corporations say— millions will be out of work, the children of America will be penniless beggars in the street—in short, the entire country destroyed by a single tax hike. Such whiners want us to forget that capitalism is tough and resilient. Whatever happens, capitalists will find a way to make a profit—a way to stay in business. That’s one of the great redeeming characteristics of capitalism. But

not everyone applauds, as we see in our next visual aid. Some still see

disaster ahead despite my reassuring them. For Rick McKee, Biden’s plans

are summed up as a giant tax-and -spend bomb with the fuse already sparkling.

The Republicon elephant is horrified; the Democrank donkey, astonished. Dick

Wright sees Biden’s “massive spending” as a huge wave, curling over Biden,

who says, “Things are looking up”; but he’s so disoriented that “up” could be a

catastrophe when the wave crashes. Steve Sack’s imagery shows vividly how far short of Biden’s expectations the GOP’s counter-proposal is: the difference between a real train and a toy. And Dave Granlund’s image analyzes the situation in the Senate where one vote, in this case, fellow Democrank Senator Manchin’s, could spell defeat for Biden’s agenda. In our next array, Mike Smith’s conversation between Biden and the GOPachyderm reeks irony when the elephant seems to call for unity when his behavior demonstrates his lack of it. Next, Dave Whamond creates a little high comedy drama by taking literally the rumor that Biden’s climate control plan would eliminate beef from America’s diet. It’s true that raising cattle is energy-intensive and, Zack Beauchamp in Vox.com says, combined with the methane gas released by the digestive processes of hundreds of millions of arm animals, creates more than 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, adds Jennifer Barckley at TheHill.com, animal agriculture causes mass deforestation, uses a quarter of the world’s scarce freshwater supply, and produces billions of gallons of polluting animal waste a year. So it’s easy to understand how some people might think Biden is going to ban beef, creating the situation that Whamond capitalizes on. “Where’s

the beef?” resurrects a campaign slogan of bygone times, which, itself, echoed

a television commercial. John Darkow’s visual metaphor refers to my favorite childhood hero, Robin Hood, who robbed the rich to give to the poor. And Robin Hood’s response to the rich guy’s question is exactly logical. Next Michael Ramirez calls up an image and a circumstance that I’m surprised to see. He draws Biden as Wimpy, the persistent mooch in Popeye’s comic strip who was always willing to pay tomorrow for hamburger today, as he is here. It’s a workable characterization as a criticism of Biden’s plans, but I’m surprised Ramirez thinks the average newspaper reader today would remember Popeye or Wimpy. Oooops. I take that back: the average newspaper reader today is 60 or older. Guns

and the lack of control thereof will always be with us, I suppose, and in our

next exhibit, Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins) echoes that

sentiment in “The Never-Ending News” from The Nib, an online political

cartoon site, where the breaking news of the next mass murder interrupts the

previous “most recent” report of a mass killing in a “never-ending”

progression. Next is Jack Ohman, who, in the imagery of two panels,

contrasts half-staff and full-staff to show the power of the National Rambo

Association (NRA). That power may be evaporating. NRA’s leader, Wayne LaPierre, has been accused of misusing charitable donations for lavish personal lifestyle. LaPierre sought to escape the suit by moving NRA from New York, the suit’s venue, to Texas, where he filed for bankruptcy for NRA. But the court dismissed NRA’s petition, saying the group was not acting in good faith but using bankruptcy court to gain unfair litigation advantage. LaPierre apparently can’t make up his mind. In a letter to NRA membership, he said “the NRA is not ‘bankrupt.’” Back to the other business at hand, we have an appearance by Mitch McConnell (seen leading the parade in Ohman’s cartoon), who, in eight panels from Kevin Siers, enacts the irony of his so-called position on gun control: he condemns the Democranks for behaving exactly as he is behaving.

AND

BEFORE YOU KNOW IT, we’re back at full-fledged editoonery—on gun violence. In

the accompanying visual aid, Dave Whamond provides an image and a bitter

comment. All the thoughts and prayers we summon up at each mass murder come to

naught: it’s like shoveling them into a blast furnace, precisely the visual

metaphor Whamond deploys here. The bitterness surfaces with one of the

characters’ shouted illogical instruction. Rob Rogers uses two panels to

compare and contrast public response to two separate terrors: six cases of rare

blood clots cause more consternation in this country than 147 mass killings. Just below is Matt Davies highly comedic (and ironic) comment that helps explain why mass murders arouse so little response. “It can’t happen here,” the innocent bystander says, while pasting another “here” arrow on the map, already wildly cluttered with “here” arrows that assert while denying. Clay Bennett gives us our final comment on gun safety in a gun violent society: the powerful image of a lone figure throwing away his gun. The

next exhibit begins with Jen Sorensen’s comic strip (and it is, indeed,

a comic strip—not just a parade of individual panels), which, like the authentic

article, builds, panel by panel, to a conclusion. Organized baseball reacted to the Georgia laws by moving its All Star Game out of Georgia, thereby punishing the state. Rob Rogers celebrates that maneuver by re-designing the Major League Baseball logo to show the silhouetted MBL player about to bash a crow named Jim with his bat. Then Mike Luckovich collects a bunch of GOPachyderms who, tiki torches aloft, re-enact the street scene from Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, when neo-Nazis and white supremacists paraded in support of a statue of Robert C. Lee; here, Luckovich has re-directed their ire to voters generally rather than just liberals (and, presumably, other cancel culture advocates). At the lower left, Bill Bramhall creates an image that combines two targets: 1) the new Georgia law that prevents someone from giving voters in line a drink of water on a hot day and 2) cops who are too eager to resort to force to control a crowd (or a water dispenser). The water carrier utters the famous cry of those protesting in favor of Black Lives Matter. The

tension between law enforcement and members of African American communities persists,

with George Floyd as the rallying cry for the latter. In the next array, Rick

McKee’s stunning graphic suggests the George Floyd influence is widespread:

his death has cast a long shadow from gravestone to the scales of justice. Rob

Rogers uses two panels, setting up a circumstance in the first only to

destroy it in the second, in which George Floyd’s dying words echo ominously.

Then Drew Sheneman’s imagery compares the amount of training various

professions get. Realtors and hairstylists get more training than a police

officer gets, and his job includes carrying and perhaps using a lethal weapon. The image Michael de Adder offers at the lower left is of an amateur cover-up, aimed, we suppose, at preventing the public from knowing what the tell-tale cameras know. During

the pandemic, masks became political symbols as well as health preservers. Pat

Bagley uses the comic strip format in our next visual aid to reveal the

idiocy of those who refuse to wear a mask because “nobody tells me what to do.”

And yet, ironically, in Bagley’s scenario, the guy refusing to wear a mask is

doing exactly what others are telling him to do. The mandate to wear a mask is evaporating as I type this, but when Mike Smith drew his cartoon a couple weeks ago, it was still in force in most states. In the second panel of his editoon, Smith reveals that many Republicon governors wear the mask “incorrectly”— i.e., covering their eyes in order to avoid seeing something. Next, Smith goes after the Texas governor, who violated the mask mandate by lifting it in his state. In his comparison, people must wear shoes and shirts for service in this coffee shop. But they don’t have to wear life-saving masks. We

have shut down the Trumperies Department, and without Facebook or Twitter

platforms, the Trumpet is much less visible than he used to be. But he’s still

there, lurking on his golf courses and waiting to pounce on unsuspecting

citizens. Nick Anderson’s image on the next array shows the Republicon

pachyderm still at Trump’s service —here, acting as a tee for Trump’s next

swing. And Mike Smith repeats the message with a different visual

metaphor—a pachyderm hand puppet instead of a tee. Bruce Plante and I harbor the same suspicion: that the only reason Trump lets it be known that he’s thinking of running in 2024 is because that knowledge encourages his cultists to donate money to his non-existent campaign (money that he can use in any trumped up excuse for a campaign without having to report to anybody about how it is used). Plante’s image, of Trump shaking money out of his supporters’ pockets, is apt—particularly with Trump wearing the mask of a robber. I clipped the photo of the Trumpet because it shows his typical visage, mouth always open, lips pursed. But if you read the caption, you’ll see that it’s about another money raising scheme that borders on the criminal.

SOMETHING

A LITTLE DIFFERENT THIS TIME. This time for our break, I’ve burrowed deep into

the Rancid Raves Storage Bin of Bygone Comic Art and uncovered the accompanying

relic of Dick Tracy art, my homage to the various artists who most visibly

worked on the strip over the years. They appear in caricature next to

their signatures—Dick Moores, Dick Locher, and Chester Gould. One whose signature may not leap to the front of your memory is Dick Moores. Moores’ earliest comic strippery was as Chester Gould’s assistant on Tracy. From there, he went on to create Jim Hardy, a Tracy look-alike, who was a sort of drifter/crime fighter. He eventually developed ties to journalism and became a crime-fighting reporter. When it started, the strip was about an ex-convict and in the first installment, the convict was released from prison. No newspaper bought the strip; who wanted a strip about an ex-con? So Moores modified it, eliminating the ex-con guise. The strip never sold very well, but it ran from June 29, 1936 to sometime in October 1942. The

last couple years, it was entitled Windy and Paddles, surrendering to

the popularity of two characters Jim Hardy ran into on his trouble-shooting

newspaper reporting travels. Windy was a simple-minded but virtuous cowboy, and

Paddles was his faithful and nearly sentient race horse. After the strip died, Moores went to work at Disney Studios, drawing various Disney newspaper strips. By the mid-1950s, Moores was assisting Frank King on Gasoline Alley, and by 1960, he had taken over the strip, writing as well as drawing. He continued for the next 25 years or so, producing one of the medium’s most memorable creations, a warm experience in man’s humanity to his fellow man. For more about Gasoline Alley, consult Harv’s Hindsight for November 23, 2008. But until you abandon this vessel for that one, we plunge onward with Editoonery for the past month.

NOW, BACK TO WORK, analyzing and understanding the use of imagery in editorial cartoons. And we have three beauts in our next exhibit. But the first editoon this time is one of Tom Tomorrow’s strip-format efforts. In it, he has a couple Ordinary Citizens spouting off all the reasons for not getting vaccinated—a veritable catalog of shithead logic. Some

anti-vaxxers fear getting vaccinated because they believe coronavirus vaccines

cause reipients to “shed” proteins that can cause infertility and miscarriages. Then Adam Zyglis offers a visual metaphor for the fight against the pandemic: Covid-19 is a fire, which firefighters are striving to put out. Their effort, however, is frustrated by an Anti-Vaxxer, who’s sitting on the firehose, preventing water from reaching the conflagration. Below Zyglis, Chris Britt carries on in much the same fashion with an image suggesting that Death Itself applauds what the Anti-Vaxxer is doing because it results in more people falling into his clutches. Finally, Bill Bramhall produces a visual metaphor in which Anti-Vaxxers are a dead weight that all of us must drag down the road if we are ever to get to Herd Immunity. The next display begins with Robert Ariail’s comic strip, the format permitting him to present a three-panel setup for the last panel’s punchline, a sarcastic statement from God himself. Then Steve Sack adopts the same format in order to build to his conclusion, which shifts targets as the anti-masker gets alarmed by migrant children crossing our southern border. In Matt Davies two-panel strip, the target again shifts: the chosen mask

changes a black man to a white one, achieving a measure of safety. To celebrate the supposed end of the pandemic, John Darkow calls up an iconic image of victory—that sailor kissing a nurse on Times Square in New York when Victory is declared ending World War II in Europe (i.e., V-E Day). In

the next visual aid, Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher supplies a full-page comic

strip, each panel dramatizing a situation in which a vaccine would be most

welcome—the political ills of 2021. More

political machinations are the focus (focii?) of our next exhibition. Jack

Ohman is one of many editoonists who took a shot at Mitch McConnell for his

tone-deaf advice to corporations to stay out of politics (when he, and all the

rest of these professional pols, could not exist without corporate donations).

Ohman’s image amply displays the presence and therefore influence of corporate

donors. Bill Bramhall takes two panels to reveal the GOPachyderm’s preoccupations, trivial when compared to FDR’s. Next around the clock, Joel Pett uses the image of a loooong list of liberal wishes to compare Democrank and Republicon legislative agendas. All the GOP wants to do is to be re-elected every time an election rolls around. Next, Pat Bagley resorts to the image of a highschool yearbook to reveal the fascist ambitions of Fox’s Tucker Carlson. Mike

Luckovich makes a laughable analogy about Republicon attitudes about

winning and losing to get our next visual aid off and, er, running. The image

is of a track race that Republicons think they’ve won when they only come in

second. I saw relatively few editoons about the renewed hostilities in the Mideast—perhaps because the struggle is too deadly and therefore grievous for cartooning. So when Daryl Cagle showed up with one just as I was wrapping up this All-editoon Edition of Rancid Raves, I seized it and stripped it in here. Cagle starts with an image of two doting mothers watching their children “playing Israelis vs Palestinians”—“How cute,” says one. But playing deteriorates into a life-and-death struggle, ending in death for both combatants. Cagle’s visual metaphor suggests that the nastiness between Israelis and Palestinians is, if not infantile, at least childish. But of course it isn’t. It’s deadly serious. It’s as if the Jews, having endured centuries of deadly abuse as an ethnic/religious group, decided, once they had their own country, that they would “take it’ no more. They would strike back rather than suffer in silence, and they’d strike back immediately. And so they have. And why did others start beating up on Jews anyway? Because they were brazenly different: they worshiped only one god while the rest of us worshiped many. We conclude this array with a photograph of a nondescript albeit sleazy man selling Dr. Seuss books on the sly as if they were dirty books. A perfect sarcastic response to the current kill Dr. Seuss campaign.

AFGHANISTAN AGAIN. We’re pulling our troops out of Afghanistan on September 11, on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 catastrophe that was brought about by extremist Muslims plotting together in Afghanistan when no one was watching. Our troops have been there ever since in the belief that by their presence, we can prevent a recurrence of a plan to destroy us again, a plan formulated by extremist groups, working freely in Afghanistan, without any governmental oversight. Afghanistan as a haven for Islam extremists would make Afghanistan the breeding ground for another assault on the U.S. We wanted to prevent that, so we stayed in the country. But then we got bored. And we failed to wipe out the extremists. And right-thinking Americans began demanding, aloud—even in newspapers—that we get out of Afghanistan. So that’s what we’re doing. We’re reasonably good at it. We’ve done it before. In Vietnam. We’re couching our withdrawal from Afghanistan in terms that suggest we’ve won some sort of victory there. We met with the Taliban and agreed to leave if the Taliban refrained from acts of violence against the Afghan government for a designated period—six months, I think it was. The Taliban have continued killing civilians and fighting the government’s troops. But we ignore that and pretend that the Taliban are being good, obeying the restrictions of the agreement, because that will permit us leave. And we desperately want to leave. In effect, we just throw up our hands—helplessly— and give up. But we pretend we’ve won. Afghanistan is not a nation. It’s not a country with a social order and a government. It’s never been a nation. In the whole long history of Afghanistan it’s been nothing more than a geographic entity populated by war lords and their constituents. Countless other Western nations have tried to conquer Afghanistan, to convert it to something that functions as an entity of some kind. None have succeeded. Afghan troops fade into the hillsides and wait until the Western power gets bored and leaves. Then they all come out of hiding andrun the country again. The Taliban is a war lord’s gang. They want to return to a time when their will on all matters is obeyed because it is religiously based. Keep women at home. Keep women’s hair covered. What is the erotic appeal of women’s hair that sets the Taliban free to rampage and rape? I don’t get it. And that’s the trouble. We in Western Civilization don’t understand a war lord society—a society, let’s admit, that’s been at war within itself for generations. Forever. And we propose to change this? Not likely. We’ll leave, and the Taliban will quickly take power all over the country, getting all the war lords to swear fealty. Women will once again be restricted to home life. They’ll cover their hair. And we’ll pretend that’s okay with us, women’s right to be human notwithstanding. That’s why we’re hearing these days that the Taliban have no ambitions beyond the borders of Afghanistan. If that’s true (and it isn’t), we can feel safe. But the Taliban consists of religious fanatics. And religious fanatics are never content: they always want more—more adherents, more fervently obeyed. And so the Taliban will soon be threatening us again. And we’ll react by sending troops back to Afghanistan. And we’ll bemoan it. The Longest War again. Why not? Why not just turn Afghanistan into what it has almost been for a dozen years or more? An American military training camp that does its training of troops with real bullets against real, live enemies. Make our presence there permanent.

EDITOONS

ABOUT OUR PENDING departure from Afghanistan sometimes touch on the matters

we’ve just reviewed. In the first editoon of the nearby display, Joel Pett recalls

the fruitless invasions of other countries—Russian (the bear), Genghis Kahn,

Alexander the Great, even Hagar the Horrible (just for a chuckle). They all

tried to conquer Afghanistan. They all failed. We’re joining a company of

distinguished failures. Next around the clock, Bill Bramhall’s image presents a typically misguided opinion about Afghanistan, one that reflects the usual Western myopia about other cultures and adventures beyond our borders. Uncle Sam doesn’t see what’s happened to the Afghan limping along behind him, and with customary obliviousness, he simply walks away, secure in his ignorance. Next, in Drew Sheneman’s visual metaphor, American soldiers must “exit gracefully” from atop a pile of timber (railroad ties, it looks like) on which they’re precariously balancing. How to get off the pile? Looking at it, it seems impossible. Steve Greenberg gives us a telling image: Uncle Sam reading the Vietnam Playbook on how to leave the country while at the same time propping up the current President of Afghanistan. And the letters that you can’t spell Afghanistan without? AGAIN. The last word on Afghanistan is never the last word. In

the next exhibit, Lisa Benson offers a metaphor for our tendency to rush

to judgment before ascertaining the facts—a tendency leading to certain death,

as with lemmings— and then Nick Anderson shows how Democrantz and

Republicons differ in their efforts to save the drowning soldier. Leave it to

the GOP to maintain their distance from reality. Makes you wonder: do any live

Republicons ever read editorial cartoons? Can’t they see what fools they’ve

become—how readily their behavior fits into cartoon comedy? In a series of panels, Mike Luckovich builds an image of the GOPachyderm that shows it disturbed by a relatively small number of kids crossing the border compared to much larger number— the deaths from Covid-19. With his sidewalk image of the Trumpet blaming China for the pandemic and chalk outlines of the dead on the street, Rob Rogers suggests a connection between Trump’s accusation and a rise in anti-asian hate crimes. In

the next array, we start with David Hitch, whose spectacular

cross-hatching technique always stops me cold in a posture of outright

admiration. Here, he’s attacking Biden for promulgating a confusion of rules

about mask-wearing. Next around the clock, Dick Wright takes “packing

the Court” literally and shows how the Supreme Court will look if the Democranks

are successful in packing it by increasing the number of justices: then,

they’ll have complete control. Then Pat Bagley summarizes the Matt Gaetz situation. Public officials who get caught up in sex scandals because, presumably, they’ve traded on their power to gain the favors of otherwise disinclined women are juicy low-hanging fruit for the news media to pick, and Gaetz is proving to be the ideal can’t-keep-his-pecker-in-his-pants candidate so far. He denies everything, of course, but late-arriving testimony from a colleague may yet upset his apple cart. Then we have an anniversary celebration at Humor Times, now 30 years old. This monthly tabloid is one of my chief sources of editoons for Rancid Raves, so, naturally, I recommend subscribing: mail in one-year subscriptions are $26.95, but if you subscribe via the website (humortimes.com), there’s a $4 discount. In addition to printing the latest editoons, Humor Times also carries a healthy load of text columns, including Jim Hightower’s Lowdown (online and in print) and my own Funnies Farrago (online only; it reprints articles from Rancid Raves— recently, a piece on how Hilda Terry challenged the "all-boys" National Cartoonist Society in 1949 with a wonderfully sarcastic letter, and ended up winning membership for women cartoonists). Another of my dependable sources is The Comic News, another monthly editoon tabloid, which is celebrating 36 “inexplicable years.” Rates begin at $33/year for the print version; $10/year for the online version. There’s a website, thecomicnews.com ; and a P.O. Box 8543, Santa Cruz, CA 95061. Subscribe at either. After that smattering of plugs, you deserve a break.

AGAIN

THIS TIME for our break, no lectures, no history. Just weirdly comedic

cartoons. I love this stuff—particularly, here, the opening cartoon. Took me a

while to see the gag. You have to pay attention with these things.

BACK

WITH OUR NOSE TO THE GRINDSTONE (try working in that position), John Darkow takes a look at “the talk”: on the left, the traditional “talk” a Black father

(or mother) is obliged to give his children when they are old enough; on the

right, the “talk” policemen ought to get as part of their training. It’s the

cop’s insistence on “controlling” everything like a Russian czar that fosters

the trouble that too often winds up with gun shots. Next, Dave Granlund deploys

an image of Moses with the commandments to display the apparent contradiction

inherent in the Pope’s latest pronouncements on gays. And Pat Bagley shows up another contradiction in his portrait of an irate Supreme Court justice, namely Brett Kavanaugh, who, in a recent ruling about young offenders, takes a position that would have condemned his appointment to the Court had the Senate agreed with him. At the lower left, Bob Englehart takes four panels to let Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg instruct the Trumpet on the conventions of social media as they apply to Trump’s new personal platform and (not) to Facebook. Upon opening his new website, Trump generated only 212,000 likes and shares compared to his Twitter following of 88 million and his Facebook following of 32 million. Trump nonetheless said blogging was “more elegant” than tweeting (as quoted from The Week, May 21). For

our last lesson, Tom Tomorrow returns to impersonate the Fox channel’s

talking heads. Under his tutelage, they manage to misinterpret every event of

the day’s news, confirming, as they do, the Republicon position on every issue. John Just below Darkow, Joe Heller conjures an image that takes a jaundiced view of life after the relaxation of the mask mandate. On Earth Day, a worker faces a clean-up of discarded masks that prompts his somewhat sour reaction. Finally, Jimmy Margulies’ image responds to Amazon’s way of dealing with its workers’ union. The Amazon arrow, which normally goes from ‘a’ to ‘z’ (yeh: that’s the significance of it) just spears the worker, through and through.

MORE COVER EDITOONING Before we take our leave of this survey of the last month’s editorial cartooning, let’s take a look at the cover of the Washington Examiner. I just started a subscription to this rampant right wing-nut periodical. That will doubtless surprise you—that I, a rampant left wing-nut would subscribe to a publication so steadfastly opposed to my own biases and prejudices. I wish I could tell you that I subscribed in order to become familiar with opinions other than my own. Give the other guy a chance, so to speak. But I didn’t. I subscribed because the subscription rate was astonishingly low, and I thought—wot the hell; let’s see what it has to say. And when I opened my first issue, I was astounded to see how rampant the right-wing opinions are deployed throughout the magazine. There’s no pretense at objectivity: everything is re-cast in terms that support the right-wing’s views. Sometimes cunningly (albeit predictably). In one case, the Examiner quoted the Washington Post, finding support in an unlikely place, a notable left-leaning newspaper. How did that happen? Has the Washington Post abandoned its liberal perch? Nope. It was done in the time-honored manner: the Examiner quoted just a portion of a sentence in the Post, a portion that seemed, out of context, to support the Examiner’s position, even though the full sentence didn’t. For example (I made these up)—: Original sentence: That Joe Biden’s plan for America’s future is extravagant beyond belief is now apparent to all, and it cannot help but change America for the better. Misquoted: Joe Biden’s plan for America’s future is beyond belief and it cannot help but change America. Abuse of quotations is child’s play. But we seldom see it so blatantly deployed. Alas, I didn’t keep the actual quotation at issue here; I must’ve been asleep at the switch. The experience warned me off the Examiner’s reportage, which I now glance at and move on to the book review section. But I am enjoying my subscription to this right-wing rag because it uses full color caricatures in editooning poses as brilliantly executed cover illustrations. Again, asleep at the switch, I clipped the cover illos but forgot to note the names of the artists. Maybe I’ll collect them as we go along. In the meantime, here’s a selection of cover artistry that I enjoy for its artistry if not its opinions.

FRONT PAGE DUFFY When we wrote about editoonist Brian Duffy at the Des Moines Register a couple months ago, we should have recalled a distinction that editoonists had at that paper. For over a hundred years, saith St. Wikipedia, the front page of the Des Moines Register featured a daily editorial cartoon, establishing a tradition of political commentary in Iowa—and notoriety throughout the country. Geneva Overholser, editor of the paper in 1994, correctly assessed the role of the front page cartoon in a Foreword to a collection of Duffy’s cartoons: “What makes a newspaper’s personality? Some big things, like how the paper looks or what sections it’s divided into. And some individual things: the voice of a prominent columnist, for example. Or the work of a cartoonist. “The cartoonist is always a powerful part of a paper’s personality. They use humor, which people like. They work in an unusual medium—and it’s a medium that makes for exceptionally pointed commentary. “At

the Register, the cartoonist is even more prominent than usual

because—as any true Iowan knows—we play our cartoonist right out front. We’ve

done so for as long as anyone scan remember. In the old days, lots of

newspapers did it this way, operating on the philosophy that you put a

selection of your very best work right out for all to see first. But other

papers, over the years, quit. We didn’t. “Now, our front page is known throughout American journalism as the one with the cartoon on it.” And we wish more newspaper editors felt this way. But, sadly, they don’t. In 1906, the Register hired Jay N. “Ding” Darling, who drew for the newspaper until his retirement in 1949. Darling was temporarily succeeded by his long-time assistant, Harold I. “Tom” Carlisle, who occasionally produced cartoons in Darling’s absence and after his retirement. In 1953, the Register hired editoonist Frank Miller, who remained with the newspaper until his death in 1983. And then Brian Duffy became the full-time staff cartoonist. Duffy drew for the Register until 2008, when his position was abruptly terminated during budget cutbacks. Together, Darling, Carlisle, Miller, and Duffy produced a century of cartoon commentary and their drawings provide a unique view into the past from the front page of a regional newspaper. But that perspective is gone. The Register gave up on front page editoonery when Duffy left. Neither editoonist nor readers enjoy that display today.

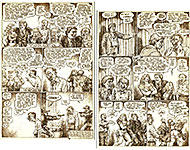

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words Not

that we’ve banished words forever from this department. We need just enough to

tell you what you’re looking at. First, to commemorate our 22nd anniversary, here’s a rare instance of cartooning: it’s a full-page comic

strip—like a page from a comicbook, except this page is a complete story

in-and-of itself. And if you look closely, you’ll see that this story can be

told only in a comicbook/comic page format. Nowhere else. The

other illustration is of the label on a bottle. It’s a bottle of my favorite

beer, appropriate for this celebratory occasion. But the maker doesn’t call it

“beer”; made in Austria, it’s called a “malt liquor.” Or “the world’s most

extraordinary beverage.” One of the things that makes it extraordinary is that

the brewer produces all of the year’s supply on one day— December 5. The other oddity is the name of the beverage. Samichlaus. Which is? Look at the accompanying illo carefully and you’ll see the answer. Oh—the four figures at the bottom of the page? Three characters, actually—one appears twice. They have absolutely nothing to do with Samichlaus. To remind yourself of who they are, visit Harv’s Hindsight for January 2019. And that’s about all we have this time at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer, which we’ve tuned up especially to commemorate having completed our 22nd year of biweekly postings.

PERSIFLAGE & BADINAGE A day can really slip by when you’re deliberately avoiding what you’re supposed to do.—Bill Watterson It’s not whether you win or lose but how you place the blame. You’re not drunk if you can lie on the floor without holding on. We have enough youth. How about a fountain of smart?

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Sometimes happy, sometimes blue, But I’m so glad I ran into you--- Tell the people that you saw me, passin’ through

M. Thomas Inge, 1936 - 2021 I never asked him what the ‘M’ stood for. Probably because we had plenty of other things to discuss. Although now, if you asked me what we talked about, I couldn’t tell you. What I can tell you is that we were fated to meet. In the fall of 1978 (or perhaps during the ensuing winter), I decided to write down my theories about how comics work—how their success depends upon a blend of words and pictures to achieve a meaning that neither words nor pictures attains alone without the other. I entitled the essay “The Aesthetics of the Comic Strip” and submitted it to the Journal of Popular Culture. And then, I mostly forgot about it until I was reminded the following spring. In the spring of 1979, I was in Kansas City doing a site inspection. My full-time job was as convention director for the National Council of Teachers of English, and NCTE was considering Kansas City as a site for a future convention. My role was to inspect such site candidates and write a report outlining the convention facilities at each of the sites being considered. When I phoned my wife one evening, she told me that I’d received a phone call from Thomas Inge, who wanted me to call him back. I’d never met him and barely knew the name, but that was enough. The next day, soon after I’d arisen, I phoned the number my wife had given me. When Tom answered, he told me that he was the guest editor of the Journal of Popular Culture’s special issue that would be devoted to scholarly treatment of comics and cartooning. And then came the fated part: he said he had planned to invite me to write for that issue an article exactly like the one I’d written and submitted. Obviously, the fates intended that we should meet. And become friends. He had been reading my column on comics and cartooning, history and lore, in the Menomonee Falls Gazette, a weekly comic strip tabloid to which I’d been contributing since October 1973. Subsequently, I drew cartoon headings for each of the Journal’s special section articles on cartooning—and another cartoon for the cover of the Journal’s Spring 1979 issue (XII.4).

And Tom and I became friends. We’d run into each other at comic conventions or at the periodic “festival” of cartooning held at the Cartoon Research Library at Ohio State University (eventually retitled The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum—I love the ampersand). We always had dinner or lunch together. A dozen or so years later, we were on the phone together. I can’t remember whether he had phoned me or I had phoned him. At the time, Tom had become a special consultant on popular culture for the University Press of Mississippi, a role he filled for the rest of his life. The University Press had published his Comics As Culture in 1990. And now, as it turned out, he had another book in mind. At one point in our conversation, he said something like: “With all the writing you do about cartooning, by now you must have enough material that you could, with very little work, turn it into a book-length production.” He had in mind a book like his Comics As Culture: a book with an umbrella title that would embrace a collection of miscellaneous articles. And so with his encouragement, I pulled together about 20 articles on comic strips, cartoonists, and comic books, strung them together, and submitted them to the Press. They decided that they would like to publish such a book, but what I’d submitted was too long. If I could reduce it by 50 percent, they’d publish it. I did, and they did. In 1994. The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History. Even before the book was in print, they wanted to publish a sequel, using the material I’d deleted from the original manuscript. That material was exactly half of my original submission, and it was published in 1996 as The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History. Yes:

that’s right: Tom Inge is responsible for my subsequent career as an author of

books about cartooning and And with that, you see the reason for this long personal anecdotal essay. Just as Tom, acting in his Press role as consultant, nudged me into writing books about cartooning, he also nudged others to produce serious, scholarly books about comics and other aspects of popular culture. Tom Inge is not only one of the earliest academics to teach and write about comics: he was also a mover and a shaker in developing an entire field of scholarly endeavor. I don’t think anyone else can lay claim to such an achievement. And here, my preface ends, and I turn over the remainder of this fond obituary to others, to wit—:

OBITUARIES FOR INGE customarily begin by calling him a trailblazer, a pioneer, in comics scholarship—to which I might add that he was virtually the creator of comics scholarship. Most of what follows, I’ve taken from an article by Brian McNeill, University Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University. I’ve added a little here and there from other obits. Legendary comics and pop culture scholar M. Thomas Inge, Ph.D., who taught in the Department of English at Virginia Commonwealth University in the 1970s and whose donations of comics, art, fanzines, correspondence and memorabilia serve as the cornerstone of the Comic Arts Collection of VCU Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives, has died. He was 85. Inge, who was the Robert Emory Blackwell Professor of English and the Humanities at Randolph-Macon College, was among the first academics to teach about comics and was one of the earliest scholars to write about comic strips, graphic novels and comic books. He was the author of more than 50 books, including the three-volume Handbook of American Popular Culture — cited by the American Library Association as an outstanding reference work in 1979 — and Comics as Culture, a groundbreaking 1990 exploration of the history and development of American comic art. [At the end of this article, I’ve listed the titles and their authors of other early comics publications so that Inge’s place in the pantheon is vividly apparent.—RCH] He maintained a steady influence on the field by serving as general editor of the Great Comic Artists and Conversations with Comic Artists series published by the University Press of Mississippi. In the 2017 book The Secret Origins of Comics Scholarship, Inge is mentioned frequently as “a shaker and a mover in the field of comics scholarship for over 40 years.” Among Inge’s many contributions to the Comic Arts Collection are unique items such as a copy of Secrets Behind the Comics, a 1947 book by Stan Lee, co-creator of Spider-Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, Iron Man, Thor and the X-Men, that is autographed and signed to “Titanic Tom Inge.” VCU Libraries’ M. Thomas Inge’s papers collection includes materials documenting the scholar’s activities and interests related to comic arts, popular culture, and American literature. The collection features correspondence from noted artists and writers such as Art Spiegelman, Mort Walker, Bruce Duncan and Harold Foster in addition to manuscripts of Inge’s scholarly works. Newsletters, fanzines, and trade publications as well as animation cells, buttons, and other memorabilia are also included in the collection. “Tom was a beloved friend and ardent supporter of VCU Libraries,” said Yuki Hibben, interim head and curator of books and art for Special Collections and Archives. “It was his vision to build a world class research collection of comic arts materials to inspire students, scholars, creators and fans, and his contributions made this possible. His warm and gracious presence will be dearly missed.” Hibben worked closely with Inge and his family for many years. Within a recent year, Inge donated nearly 200 linear feet of papers and books along with his treasured collection of original comic art. Cindy Jackson, library specialist for comic arts, said Inge was a trailblazer in the field of comics scholarship. “We would not be where we are today in the field if it was not for his love of comics and his dogged persistence that comics were a literary art form and not just disposable entertainment for kids,” Jackson said. “The literary world has come around to his way of thinking and now there is all kinds of exciting research being done in the world of comics. “The things I will always remember about Dr. Inge,” she added, “were his kindness and generosity. He always made time to talk to students and scholars researching comics. He was free with his knowledge and was always enthusiastic with his support.” Milton Thomas Inge was born on March 18, 1936 in Newport News, Virginia, son of Clyde Elmore and Ernice Lucille (Jackson) Inge. As he grew into his teenage years, he wanted to be a cartoonist. He eventually abandoned that goal when he discovered that he loved literature and wanted to teach. Inge earned bachelor’s degrees in English and Spanish from Randolph-Macon College in 1959 and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in English and American literature from Vanderbilt University in 1960 and 1964. After teaching at Vanderbilt, he joined the faculty of the Department of American Thought and Language at Michigan State University. There, in 1968, he taught the first accredited course on American humor, and taught how comic strips can be considered an important source of cultural identity. He came to VCU in 1969, shortly after the university was formed by the merger of the Richmond Professional Institute and the Medical College of Virginia. He taught in the English Department and served as chair from 1974 to 1980, and then was Head of the Department of English at Clemson University in South Carolina. From 1982 to 1984, he was appointed Resident Scholar in American Studies by the U.S. Information Agency in Washington. He was on the faculty at Randolph-Macon for more than 30 years, teaching popular American Studies courses, including American Humor, Graphic Narrative, Animation in American Culture, and Walt Disney’s America. During the 1990s, Inge wrote the acclaimed essay, "Was Krazy Kat Black? The Racial Identity of George Herriman" for Drawing the Line: Comics Studies and Inks, 1994-1997, edited by Lucy Caswell and Jared Gardner (Ohio State University Press, 2017): 40-51, which has completely transformed the study of George Herriman's work in the years since. His 1995 monograph, Anything Can Happen in a Comic Strip: Centennial Reflections on an American Art Form, was also a seminal work in comics study. Inge continued to shepherd others into producing historical essays and books of research and reportage. Mike Rhode tells of his experience with Inge (in italics)—: Tom and I probably met at a convention, but we became better acquainted when I was called up from the minors to fill in for two Harvey Pekar interviews at SPX. I did them, and then transcribed them for John Lent's International Journal of Comic Art. Not wanting to miss a wider audience, I offered them to Tom for whomever might do a book in Tom's Conversations with Comics Artists interview series at the University Press of Mississippi. Tom instead wrote back, changing one direction of my life: "How about your doing the Pekar volume in the Conversations series? I don't have anyone signed up for him, strange to say, and you already have two interviews I assume. Have you resources to locate the previously published ones? " Never having edited or compiled a book before, I wrote back that I'd think about it, and then a day later— "Tom, I'm still mulling it over although I'm leaning towards doing it" (July 20, 2006). So I did it, and Harvey Pekar: Conversations came out in 2008. Not learning from experience, I wrote to Tom about doing a collection of Herblock interviews. He responded favorably to me and the Press editor. Alas, the Herblock Foundation, which controls the rights to everything having to do with editoonist Herb Block’s life and art, didn’t warm to the idea, and Rhode retired from the editing game. About Inge, though, Mike summarizes: “Tom was one of the best and most productive members of the first group of academics to study comics. He was an immense help to my second career, and to many others, and the field is much richer for his time spent cultivating it. He'll be missed by many.” Inge brought his expertise to the Randolph-Macon campus through several of his popular American Studies courses, such as American Humor, Graphic Narrative, Animation in American Culture, and Walt Disney’s America. Inge was a renowned scholar in other fields, as well, including being one of the foremost experts on the work of William Faulkner. Inge's broader interests in literature, the image, and culture are demonstrated in two recent publications: "Mark Twain and Dan Beard in the Court of King Arthur," Illustration Magazine, No. 55 (2017): 62-81; and "William Faulkner, James Avati, and the Art of the Paperback Novel," Illustration Magazine, No. 56 (2017): 56-69. At the time this article was written, Inge was working on a study of Walt Disney and the art of collaboration for book publication. As a senior Fulbright Lecturer, Inge traveled the world, teaching at the University of Salamanca in Spain (1967-68) and at three institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (1971). On a third Fulbright appointment in 1979, he offered courses on American humor and literary regionalism at Moscow State University in the Soviet Union. As resident Scholar with USIA, he consulted and lectured abroad in eighteen countries, including France, Italy, Portugal, Japan, New Zealand, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the People's Republic of China. More recently, he has lectured in Poland, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Finland, Denmark, England, Germany, and the Czech Republic. At the invitation of the Gorky Institute, he returned to the Soviet Union to participate in conferences on Sholokhov and Faulkner and the works of Eudora Welty. He has led travel-study courses to the Soviet Union in 1988 and China in 1989, and in 1994 he taught at Charles University in Prague on a fourth Fulbright lectureship. Inge was among the founders of the Popular Culture Association and co-founder of the American Humor Studies Association. In 2018, he received the Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar Award, the highest honor offered by the PCA: it recognizes distinguished scholars who have made significant and lasting contributions to the study of popular and American culture. In 1996, the PCA established the annual M. Thomas Inge Award for Comics Scholarship to recognize works of distinction in that field. Inge was married three times: in 1958, to Betty Jean Meredith (divorced, 1970), one child, Scott Thomas; in 1982, to Tonette Long Bond (divorced, 1990), stepchild, Michael Gordon Bond; and to Donaria Romeiro Carvalho, 1998.

PIONEERING WORKS ON COMICS AND CARTOONING What we might call the modern era of comics scholarship (to separate it from the period embraced by Coulton Waugh’s The Comics, 1945, and Stephen Becker’s Comic Art in America, 1959) undoubtedly began with Jules Feiffer’s fond recollection of the comicbook heroes of his youth.

1965 -Great Comic Book Heroes, Jules Feiffer 1967 -Penguin Book of Comics, George Perry and Alan Aldridge -Flash Gordon, reprinting the comic strips; the first or second of the Nostalgia Press reprint series 1969 -The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, strip reprints 1970 -Terry and the Pirates by Milton Caniff; the sixth Nostalgia Press reprint book -All in Color for a Dime, Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson 1971 -Comics: Anatomy of a Mass Medium, Reinhold Reitberger and Wolfgang Fucks (German) -Comix: A History of Comic Books in America, Les Daniels 1972 -The Art of the Comic Strip, Walter Herdeg and David Pascal -Great Comics Syndicated by the Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, Herb Galewitz 1973 -The Comic-Stripped American, Arthur Asa Berger 1978 -Crawford’s Encyclopedia of Comic Books, Hubert H. Crawford 1987 -Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy, NBM Flying Buttress 1990 -Comics As Culture, M. Thomas Inge 1994 - The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History, Robert C. Harvey 1999 -Golden Age of Comic Fandom, William Schelly

The books in bold face are the more scholarly of this listing. They were the pacesetters. From the dates of publication, we can see that comics scholarship, particularly of the history sort, ran through the 1960s and 1970s and then almost disappeared in the 1980s. It revived in 1990 with Inge’s book, and after that, academic and popular interest in comics proceeded apace. It would appear, all modesty aside, that Tom’s book and mine marked the beginning of the current excitement over books about comics and cartooning. And my book came about through the urging of Inge. Oddly, speaking of fate, just the week that he died, I thought I should send a note his way: we hadn’t talked much in the last few years. I may have been thinking that on the very day he died.

David Anthony Kraft, 1952 - 2021 Veteran comic book writer, journalist, publisher and agent Kraft passed away on May 19. “For those who didn’t know, David and I had been battling COVID pneumonia since April 28th. Yesterday morning, in the wee hours, he was too tired to fight anymore. He died quietly, holding my hand and looking into my eyes,” his wife, Jennifer Bush-Kraft, posted. I became familiar with the name by reading issues of Comics Interview 25-30 years ago. I still have a couple dozen issues stowed away; in them, Kraft published revealing and historic interviews for twelve years, producing, as someone said (accurately), a valuable treasury of comics history. Kraft started the magazine in 1983 and published it for 150 issues, finally abandoning it in 1995. After that, as far as I know, Kraft retired from the comics venue. What he’s been doing for the last 25 years isn’t mentioned anywhere I looked. What follows here is the rest of the Facebook notice posted by his wife. Coming from a background in rock and roll journalism, Kraft was named editor of FOOM, Marvel’s pre-Marvel Age in-house fan magazine, with its fifteenth issue in September 1976. He stayed in that position until FOOM was canceled with No.22. He would later use his journalism chops for the long-running publication Comics Interview (alternately David Anthony Kraft’s Comics Interview), which was published through an imprint of his Fictioneer Books, a company he started in 1974 as a home for such authors as A.E. van Vogt, Robert E. Howard, Jack London, Otis Adelbert Kline, and Don McGregor. As a comic book writer, Kraft was best known for his stint on The Defenders, which included the “Scorpio Saga” and “Xenogenesis: Day of the Demons” story arcs, the latter of which cemented the Marvelization of Atlas-Seaboard’s Demon-Hunter, which Kraft wrote for artist Rich Buckler. Kraft was also associated with character Man-Wolf, which he wrote in Creatures on the Loose, Marvel Premiere, and Spectacular Spider-Man Annual No.3, and She-Hulk, for which he wrote all but the first issue of the character’s original series. Stints on Captain America, Logan’s Run, and World’s Finest are included in his list of credits, as are Marvel Super Special No.4 (The Beatles) and No.7 (the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band movie adaptation).

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |

1.jpg)

2.jpg)

3.jpg)

4.jpg)

5.jpg)

6.jpg)

7.jpg)

8.jpg)

9.jpg)

10.jpg)

11.jpg)

12.jpg)

13.jpg)

14.jpg)

15.jpg)

16.jpg)

17.jpg)

18.jpg)

19.jpg)

20.jpg)

21.jpg)

22.jpg)

23.jpg)

24.jpg)