|

||

Opus 386 (finished November 28, 2018). The late Stan Lee is a giant in the history of comics. Present tense: he was a giant and he’ll always be a giant. About that, no one quibbles. But what are the precise dimensions of his footprint? That’s what we’ll undertake to discover here—try to make sense of the deluge of obituary notices on the Web and what they say, and what we can say, about Stan Lee’s achievement in comics. That’s next—:

STAN LEE DEAD AT 95 Plethora Abounds ONLY ONE PIECE OF NEWS THIS MONTH is worth noting at any length. Stan Lee has left us. He died at age 95 from heart and respiratory failure. He also suffered from asiration pneumonia. And everyone is taking notice. As Rick Marschall observes: “There have been a plethora of tributes and appraisals of Stan this week, starting within hours of his death. Media canned obits; fans’ fond memories; critics jumping on his grave before he could even occupy it – carping, criticism, iconoclasm, deconstruction, revisionism.” In

Los Angeles, the city of excess, True Believing artists went right to work and

put up a Stan Lee mural, depicting Stan alongside his most “I think Stan’s contributions were enormous,” Marscall goes on, “— and I can avoid hagiography to say so. His personality was enormous, and so were his talents and instincts and ego and modesty. With great power comes great contradictions. ... “That was Stan Lee. A brilliant child – maybe several brilliant kids rolled into one – who never lost the joy of childhood. Everything could be fun, if you dreamed it right, planned it right, told it right, drew it right’ and sold, or shared it, right. At the root of it all, whatever the genre or project, Stan Lee asked ‘What if…?’ “And I ask: What if there had been no Stan Lee?” Marschall’s question shoves all the rest of the plethora into the shadows.

ENTERTAINMENT WEAKLY’S November 30 issue had Stan Lee’s name on the cover and devoted four pages (four!) to a Stan Lee obit. Two-and-a-half pages were photos, but still... The text, written by Kevin Feige prez of Marvel Studios, was mostly about Stan and his cameos in movies not about his invention of dozens of comic book superheroes. A sidebar by Anthony Breznican rehearsed the invention of Spider-Man and only Spider-Man. But the stance was essentially movies. But arriving November 20, a week after Stan’s death on November 12, EW had missed the flood. Even Time and The Week were earlier than EW. But the Web was there immediately. Right after Stan’s death was announced, the Web was awash with stories marking the death at 95 of the man some referred to as the godfather of comic books. Or perhaps just the man who reinvented them, giving them a future well into the 21st century. Or maybe, judging from all the excitement, it was the death of the Virgin Mary that was being eulogized. Here are a few of the headlines picked up by Mark Peters, who begins with a reference to the fans of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko: Not even the most ardent Kirbyite or Ditkohead argues that Lee had no part in the genesis and development of Drs. Doom and Strange and the rest. But the facts dictate that calling Lee creator, which implies sole creator, is horseshit. So are these headlines:

“Stan Lee, creator of legendary Marvel comic book superheroes, dies at 95” —NBCNews.com “Stan Lee: Spider-Man, X-Men and Avengers creator dies aged 95” —The Guardian “Stan Lee, creator of Spider-Man and Black Panther has died: report” —NOLA.com “Stan Lee dead – Spider-Man creator and Marvel Comics legend dies aged 95” —The Sun

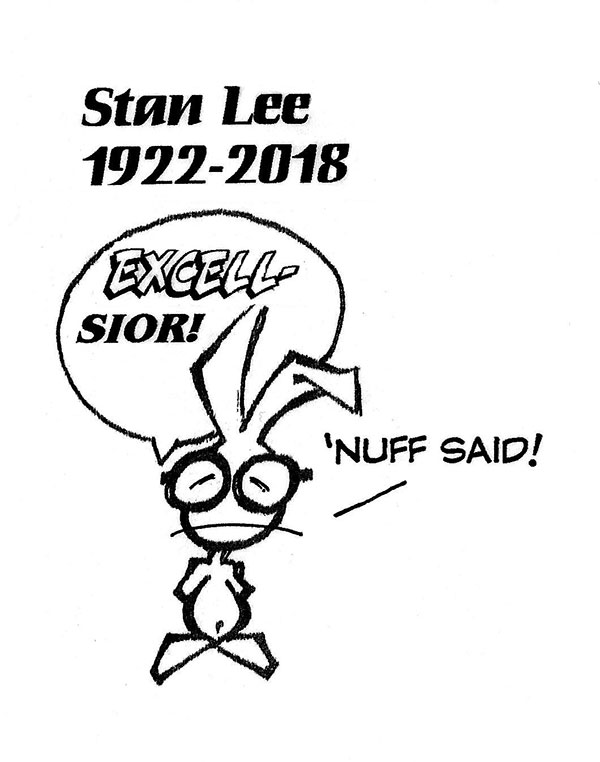

All of the above, Peters goes on, could be fixed by adding “co-” to “creator.” But that would doubtless undermine the sensation that obituary writers wallow in at the death of a celebrity. In the same vein, Peters continues (until further notice below), The Hollywood Reporter’s obit piece includes this unfortunate passage: “Lee, who began in the business in 1939 and created or co-created Black Panther, Spider-Man, the X-Men, the Mighty Thor, Iron Man, the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Daredevil and Ant-Man, among countless other characters … ” That or is doing a lot of work, because Lee didn’t create any of them. He co-created Spider-Man with Ditko, Daredevil with Bill Everett, and the rest with Kirby. There’s no shame in the word co-creation. It’s the only accurate term. While making this distinction now might sound to some like spitting on Lee’s grave, the relentless mythology of Lee as the sole genius behind Marvel has constituted an endless, geyserlike expectoration on the graves of Ditko and Kirby. An Onion headline published in the wake of Lee’s death had plenty of truth: “Stan Lee, Creator Of Beloved Marvel Character Stan Lee, Dead At 95.” Lee the character, outside his charming cameos, was not a harmless fiction. Other creators—and their legacies and families—suffered for it. Fortunately, there are plenty of ways to describe Lee that accurately reflect his monumental impact on comics and pop culture. In addition to being a co-creator of Marvel, he was the longtime editor—a job far less sexy than writer or artist, but kind of important to making sure the damn comics came out at all. As Marvel editor-in-chief, Lee shepherded a marginal comics company from the bottom of the stack to the top of the sales charts, eventually smashing stodgy DC and revolutionizing comics. Many folks (such as myself) are obsessed with the artistic genius of Lee’s collaborators. Their impact might have been much less if Lee hadn’t been such a successful and skilled editor. If “editor” sounds too mundane, there are other, more colorful terms for the work Lee did to make Marvel, well, marvelous. In his columns in each Marvel issue atop Stan’s Soapbox, Lee’s distinctive vocabulary (“Excelsior!” “’Nuff said!”) and alliterative acumen marked him as a showman, a carnival barker, a hype man, and, to use an obnoxious but accurate term, a brand ambassador. To this day, Stan is Marvel to many people, and his charm and humor are among the reasons why Marvel is beloved. Without Stan’s style, would Marvel have proven such a durable brand? We’ll never know, but I doubt it. There have been many creators with prodigious imaginations in the history of comics, but there’s never been a salesman like Stan Lee. In the spirit of Stan himself, you can even describe him in bigger terms. The following headlines are accurate and contain no slight to Lee’s collaborators:

“Stan Lee, Marvel Comics’ Real-Life Superhero, Dies at 95” —The Hollywood Reporter “Stan Lee Is Dead at 95; Superhero of Marvel Comics” —The New York Times “Stan Lee, Marvel Comic Book Legend, Dies at 95” —Variety

The truth about Stan Lee—a frustrated, middle-aged, would-be novelist who, just when he was ready to quit the business, helped reshape superheroes and pop culture—really is amazing and fantastic. Lee was equally skilled at making the sausage of monthly comics and selling that sausage as sensational (which it often was). His cameos are such a treasure even DC got in on the fun. He truly was a legend and real-life superhero—and a co-creator. That should be enough.

****

At tcj.com, Comics Journal publisher Gary Groth was a little less kind on November 13 when he heard the news. Who —or what— was Stan Lee? Editor, hustler, hatchet man, corporate player, shill, writer, frustrated novelist, success, failure, catalyst, front man, self-parody, hack, exploiter, innovator. He was, probably, all of those things. What he was, improbably enough, for at least one brief moment, and what he may have become if he had had the stomach for it, which he obviously didn’t, was a truth-teller. When I discovered a transcript of a conversation among Lee, Will Eisner, Gil Kane, John Goldwater, and others from 1971, I was flabbergasted that Lee had this to say about the industry he promoted for the rest of his life (in italics): I would say that the comic book market is the worst market that there is on the face of the earth for creative talent, and the reasons are numberless and legion. I have had many talented people ask me how to get into the comic book business. If they were talented enough, the first answer I would give them is, why would you want to get into the comic book business? Because even if you succeed, even if you reach what might be considered the pinnacle of success in comics, you will be less successful, less secure, and less effective than if you are just an average practitioner of your art in television, radio, movies, or what have you. It is a business in which the creator, as was mentioned before, owns nothing of his creation. The publisher owns it… … Unfortunately, in the comic field, the artist, the writer, and the editor, if you will, are the most helpless people in the world. The following year, Lee would join management, become the publisher of Marvel Comics, and change his tune, at least in public, for the next nearly 50 years. God only knows what he thought privately, or if he thought privately at all. (The entire transcript of this conversation is published in a book I recently edited, Sparring with Gil Kane.) Yesterday’s Los Angeles Times (November 12) quoted me from 2002 (in italics): Gary Groth, co-founder of comics and graphic novels publisher Fantagraphics Books, told The Times in 2002 that Lee's reputation rested on approximately nine years of work, from 1961 to 1970, and mostly in collaboration with Kirby and Ditko. “What he did in those nine years and what he helped Kirby and Ditko achieve — the kind of synergy they must have had working off each other — was a high-water mark in the history of the comic book,” Groth said. I think this is right, and his contribution throughout those nine years cannot, and should not, be gainsaid. What they didn’t quote me saying, however, was that compared to the careers of Lee’s two most prominent visual collaborators, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, he was virtually a creative nonentity. Naturally, he became richer and more famous than either of them. Whereas they merely had their talent and their genius, he had something far more valuable: an affable and smarmy persona that gave the American public what it always prefers: decades of vacuous pronouncements, and a smattering of entertainment devoid of content and substance.

****

STILL AT THE COMICS JOURNAL’s website, tcj.com, Michael Dean has the most comprehensive (and accurate) obituary. He begins with a conundrum: “There may be no figure in the history of comics who is simultaneously more revered and more reviled than Stan Lee.” The revered part we’ll get to soon. The reviled part probably stems from the role Stan slipped into in the early 70s when he gave up writing comics and became the company figurehead, the front man—the face of Marvel. Even before assuming the role officially, Stan was the company spokesman. When the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man began to generate buzz in a prenatal fandom, newspaper reporters came to the Marvel offices, looking for a story. They found Stan. As editor-in-chief, he was, ipso facto, Marvel’s spokesman. Surprised, no doubt, by the attention from media that usually ignored comics, Stan answered reporters’ questions. He answered in ways that promoted Marvel comics. In answering questions about how the “new” flawed Marvel superheroes came to be, he often forgot to mention the artists he worked with. Says Dean: “While it’s hard to deny that the contributions of Jack Kirby and other artists were for a long time left in the shadows by Lee’s front-office promotional role, it has proven just as difficult to deny Lee’s participation in the creative process. Numerous artists have testified regarding Lee’s passionate role-playing during plot discussions. And one has only to compare Marvel’s 1960s comics to later solo series by Kirby and Steve Ditko to see that the former have a fluid, bantering, self-aware quality that is largely missing from Kirby’s stiff, though idiosyncratically fascinating, dialogue and Ditko’s hectoring objectivist diatribes.” Dean expands these ideas in every direction to describe Stan’s role and personality. Check it out.

****

And now, my turn.— RCH: Well, it happened. Stan Lee died. It was bound to happen someday. He was, after all, 95. An age appropriate for an ending. Groth is right, I think, about Lee’s peak achievement period. And it all began because, it is always recited, he gave superheroes personalities, making them “human” rather than godlike, their archetypal role everywhere else in comics (that is, in DC Comics). That’s the Stan Lee Myth, and it began with the publication in the summer of 1961 of The Fantastic Four. But what actually happened—how the Stan Lee Myth came to be—is a somewhat more complicated story. Most things are.

In 1960, Mad was the best-selling comic book. Stan’s company, which by then had abandoned Atlas as a corporate name, was publishing a host of cute girl books (Millie the Model, My Girl Pearl, Patsy Walker, etc.), a couple romance titles, kid westerns (Kid Colt Outlaw, Rawhide Kid, Two-gun Kid), and some science fictiony Godzilla monster titles. Stan himself was moonlighting at all sorts of endeavors, including his independently produced one-shot titles like You Don’t Say!, featuring page after page of photos of politicians and celebrities onto which Stan grafted witty captions, exercising and developing his gift for verbal flippancy. Stan was wearing out, waiting for the Greatness to happen. But it wasn’t happening. And he was bored with comics. With his wife, Joan, he debated leaving the field entirely. And then one day in 1961, the publisher, Martin Goodman (a relative, by marriage to a cousin) called him into his office and told him to invent a new comic book series about a group of superheroes. At the time, the company had no superhero titles. But Goodman had heard that a new title launched by rival DC Comics, Justice League of America, was surprisingly successful at the newsstand, and it featured several superheroes, each taking a day off from his own title to work, briefly, for the League—Flash, Aquaman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, Green Lantern, and Manhunter. Goodman had made a publishing career out of imitating others, and grouping superheroes looked like a coming thing. At home that evening, Stan complained to Joan about this new assignment, which, like almost everything else he’d tried, seemed just another thing. She gave him a different perspective. He’d always wanted to do “his thing” with a comic book, she reminded him, so why not take this assignment as an opportunity to do just that. Do it “his way,” she said—and if it didn’t please Goodman and he fired Stan, well, he’d been talking about leaving anyway. It was a no risk proposition. And Stan took it. And what did he really want to write? What was “his thing”? What he wrote was the first issue of The Fantastic Four. It was not a literary masterpiece in comic book form. It was, rather, a parody, full of hackneyed superpower devices, a satire ridiculing superhero comics. In the parody, the superheroes are not superhuman: in fact, they’re only too human. While Johnny and Sue Storm spend a certain amount of time marveling (sorry) about their newly acquired superpowers, it’s the Thing, aka Ben Grimm, who single-handedly embodies Stan’s satire. The monster-size Thing crashes the frame of a doorway, complaining, as he brushes the splinters out of the way, “Why must they build doorways so narrow?” Even the Torch finds that his superpower is not an unalloyed weapon for good. Flaming through the sky, he attracts the attention of a heat-seeking hunter missile. “It’s zeroed in on me!” he exclaims, “—it’s attracted to my flame.” The quartet battles the Moleman, who, with his band of subterranean monsters, doesn’t aspire to a life of crime: no, he wants to take over the entire world. His “master plan” involves destroying everything that lives on the surface of the earth. Pretty ambitious for a comic book villain. Absurdly ambitious. And the absurdity ridicules superhero comics. In the context of 1961 superheroes—staid Superman and Batman—and Stan’s monster stories (with titles like “Xom, the Creature Who Swallowed the Earth” and “Grottu, the Giant Ant-Eater”), the Fantastic Four fit right in. But didn’t. The Moleman is a graduate of the monster stories Stan and Jack Kirby were churning out. But the Fantastic Four were something else. They were more like ordinary people than superheroes. The cover of the book should have been a giveaway. A box of type announced: “The Thing, Mister Fantastic, Human Torch, Invisible Girl—together for the first time in one mighty magazine.” An overstatement typical of satirical parody. “Together for the first time” implied that the four characters had a previous publication history. But, of course, they didn’t: this title was the debut for each of them. And any habitue of newsstand comics would have recognized the overstatement as untrue and therefore suspect. What, exactly, are we getting into? In a way, as John Wells points out in TwoMorrows’ Comic Book Chronicles: 1960-1965, Lee’s new team embodied some aspects of the company’s existing lineup: the Thing and Mister Fantastic echoed both the misunderstood monster creature and the brilliant scientist from the monster comics, and the Invisible Girl represented the cute girl titles. And the Torch set everything ablaze. After the book was published, Stan learned what he had inadvertently done. Amazingly, it was hugely popular on college campuses. Probably because college students, erstwhile superhero funnybook fans, had come to believe in their advancing maturity that superheroes were pretty ridiculous. And the Fantastic Four, in ridiculing the extremes of superheroics, were in tune with collegiate attitudes. All of a sudden, the Fantastic Four was off and running. Fan mail began to pour into “Marvel” headquarters. And Stan, shrewd enough to recognize a hit when he had one, continued in the same vein with other Marvel comics, creating the Hulk, Thor, Spider-Man, Dr. Strange, et al. All of which, one way or another, ridiculed superheroes by demonstrating that, scarcely cardboard cutout heroes, they had personalities and human defects and all that. Amazing, like I said. Lee’s cornball sense of comedy, which inspired and undergirded his interpretation of superheroics, especially at the very beginning with the Fantastic Four, was much less subtle in the four dozen issues of My Friend Irma that he wrote for Dan DeCarlo to draw from June 1950 through February 1955. In the Standard Catalog of Comic Books, Rob Salkowitz writes: “My Friend Irma was based on a popular radio and tv show featuring the adventures of the air-headed Irma and her pals, young ‘career girls’ whose amazing and incurable dumbness was the root of so much hilarity (‘Are you girls amateurs?’ asks the art instructor. ‘No,’ replies Irma, ‘we’re not even related.’) In one memorable sequence, Irma actually complained that Stan and Dan were making her too dumb—then ended up walking out with their pay checks. Excelsior!”

THE FANTASTIC FOUR in their inaugural appearance represented Stan’s view of the comic book superhero universe, DC’s universe. The book he’d always wanted to write was a book that exposed the infantile nature of superheroic comics. In shaping the expose, Stan created a satire. When the Fantastic Four proved popular beyond his wildest dream, Stan stepped back and reflected upon what he’d done. What he’d done was to give superheroes individual personalities, which, in his initial conception, satirized superheroics by contrasting the “human” and therefore slightly flawed and therefore somewhat realistic Fantastic Four with the cardboard godliness of the standard superhero of the day. In describing what he’d done, Stan telescoped it all into a single phrase: he’d given superheroes personalities. And in saying that, he left out the essential aspect that had initially inspired him—the satirical nature of superheroes with individual personalities, how such superheroes ridiculed their cardboard cut-out colleagues. Stan Lee’s singular accomplishment in creating comic books was, perforce, an accident. And it was an accident that Stan was quick to turn to advantage, cranking out more superheroes in the same mold—but different, a little, from one concept to the next. The ridicule, the satire, was quickly abandoned. Or maybe it was simply bypassed as Stan Lee comics plunged ahead in the new direction he’d accidentally discovered. In neglecting to mention the satire, Stan created the Stan Lee Myth. By making comics with superheroes who were human rather than godlike, he was the man who re-invented comics, guaranteeing them a future well into the 21st century. That’s the Stan Lee Myth. But myths, although often prompted by facts, aren’t facts. They’re true only insofar as they retain the facts that inspired them. The fact is that Jack Kirby did more to create the Marvel Universe than Stan Lee did. To see how that happened, refer to two essays in Harv’s Hindsight: “The Making of the Marvel Universe” (June 2003) and “What Jack Kirby Did” (April 2008). Still, Stan Lee undeniably had a hand in creating the Marvel Universe. He filled his signal role in an entirely unexpected way. His genius lay outside storytelling in four colors. In this endeavor, Stan was entirely conscious of his achievement. What he did was no accident. It was the result of a deliberate effort that took inspired planning and execution. In 1957, American News, which had distributed Goodman’s comic books, left the market, and Goodman, desperate to stay afloat, signed a deal with Independent News, which, as the DC Comics-owned distributor, arranged matters to stunt the growth of DC’s rival. Henceforth, Goodman had to limit his output to eight titles a month. Lee and Goodman managed to keep sixteen titles on the newsstands by converting all monthly titles to bi-monthly. But with the success of The Fantastic Four, Lee and Goodman wanted more superheroes, and Lee obliged, as we’ve seen. To introduce a comic book featuring one of the new characters, Lee had to juggle his production schedule. Each new title required that a slot in the sixteen-limitation be freed up. Lee could cancel a title outright and replace it with a new one, rename an existing title, or change features within an existing title. Lee pirouetted through all these maneuvers. As Tom Spurgeon and Jordan Raphael say in their biography of Stan Lee: “As a comic book production manager, the Stan Lee of the early 1960s was without peer. What has often been described as the startling genesis of a new way of doing comic books was really a lively but considered transformation of an existing comic book line. It would take almost four years for the first group of Marvel superheroes to be worked into the marketplace.” It was accomplished one title at a time. Or almost. Lee replaced Teen-Age Romance with The Incredible Hulk; Journey into Mystery with the Mighty Thor; Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense with Ant-man and Iron Man. In Strange Tales, Dr. Strange debuted. And in the final issue of Amazing Fantasy, along came Spider-Man.

While I appreciate Stan’s contributions to comics in the ways I’ve indicated here, the occasion of his death inspired the display online of numerous videos of Stan talking about his life, his work, and his vision. I enjoy those. Having never met the irrepressible Stan Lee in person, the videos are the next-best thing to meeting him in the flesh, mythology and all. He’s always charming and personable, scattering bad self-deprecating jokes among his recollections and judgements—all related with an unpretentious earnestness, both hands gesturing in parallel, eyebrows raised, a wink just over the horizon, a grin just under the moustache. Here are some of the videos I enjoyed watching—:

Every Stan Lee Cameo Ever (1989-2018) - YouTube—: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HnByuUqMeko

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qe7KvrCqQnU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52vrHUNyFc4

A collection of videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52vrHUNyFc4

And now, by way of an inescapable interlude—having begun with headlines, let me make this intermission with a couple that I liked:

Stan Lee Become One of Pop Culture’s Greatest Showmen—by Making Fans Feel Like Part of the Club —Michael Cavna, at the Washington Post’s Comic Riffs Stan Lee Called His Fans ‘True Believers,’ But Stan the Man was the Truest Beliver of All —David Betancourt, Washington Post Comic Riffs

****

Doug Wolk in vanityfair.com is a good antedote to the exaggerated and often incorrect encomiums deluging the Internet. Here he is—: Stan Lee’s name appears somewhere in every superhero book Marvel Comics has published in the past 50-plus years, and in the never-ending parade of movies and tv shows that has come from them. In the 60s, it was lettered in bold type in every story’s credits, almost always giving Lee top billing—no matter whether he had written it, scripted it (there’s a difference), or edited it. Later, “Stan Lee Presents” appeared on the title page of every issue, whether it had passed in front of his eyes at any point or (more likely) not. Later still, it appeared in tiny type in each issue’s indicia; in his final years, he was listed as “Chairman Emeritus.” The auspicious branding made Lee his own pop-culture caricature long before he began his string of Marvel movie cameos. In the public eye, Lee was generally perceived as the creator of Marvel’s best-known characters, the man who wrote the first decade’s worth of their adventures—injecting wild inventiveness and human depth into the stodgy old superhero genre. That’s not wrong in every way, but it’s definitely not correct. Lee’s work in his golden decade of 1961-1971 really was brilliant and groundbreaking—just not quite in the ways most people think. But of all the characters with whom Lee is associated, his greatest—and the only one he created entirely on his own—was “Stan Lee”: an egomaniac who thought it was funny to pretend he was an egomaniac, a carnival barker who actually does have something great behind the curtain. Artist John Romita, who worked with Lee on Daredevil and Spider-Man, put it nicely in a 1998 interview: “He’s a con man, but he did deliver.” Stanley Lieber initially got a job at what was then Timely Comics in 1940, through a family connection—publisher Martin Goodman’s wife was Stan’s cousin—and returned to work for Goodman’s company after his World War II military service ended. Like a lot of Jewish writers and artists, he came up with a less “ethnic-sounding” pen name for his first professionally published work and stuck with it. As he explained it later—and it’s worth noting that his explanations were often more convenient than complicated realities—“I thought comics were just little kids’ stuff, and I figured someday I was going to write the Great American Novel. So I was saving my name.” But Lee didn’t write novels by himself: he made comics, in collaboration with artists like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Romita, Don Heck, John Buscema, and others. Most of Marvel’s best-known characters from that decade were created by those artists, with Lee or on their own. (Lee noted, for instance, that Doctor Strange was entirely Ditko’s invention.) To imagine that what we read in Fantastic Four or Iron Man was Lee’s brainchild, illustrated to order by the artists, is flat-out wrong—though it’s also misleading to think of it as some other creator’s lone genius poured onto the page, then defaced by Lee’s corny gags.. Lee’s work with Marvel’s artists was unusually lopsided, as comics go, thanks to the “Marvel Method” that became his standard practice. Instead of writing panel-by-panel scripts for artists to draw, he [started with a story discussion with the artist, then] turned the work of pacing and staging, and often plotting, over to his collaborator. Sometimes [during the discussion with an artist,] he’d jump up on his desk to act out a scenario he’d envisioned; sometimes he’d simply offer a suggestion of who might appear in the next issue. Both Ditko and Kirby eventually drew stories and handed them in with little or no prior input from Lee. After a story was drawn or at least penciled, Lee’d add text, often elaborating on notes supplied by artists. As far as he was concerned, that was the “writing” part. He didn’t pretend otherwise, either. A 1966 “Bullpen Bulletins” page explains: “Many of our merry Marvel artists are also talented story men in their own right! For example, all Stan has to do with the pros like Jack “King” Kirby, dazzling Don Heck, and darlin’ Dick Ayers is give them the germ of an idea, and they make up all the details as they go along, drawing and plotting out the story. Then, our leader simply takes the finished drawings and adds all the dialogue and captions!” It’s clear that Lee did something very important; it’s less clear what that thing was, exactly. First of all, and maybe most, he was a brilliant editor and talent scout; nearly all of the artists who worked with him more than briefly in the 1960s did the best work of their careers with him, even veterans like Kirby and Romita. And for all the credit Lee gave himself, he also made sure his collaborators got their names in lights. The credits that appeared in Marvel’s comics didn’t just list names and jobs—they called attention to themselves with little comedy routines:

Script: STAN LEE, D.H. (Doctor of Hulkishness) Layouts: JACK KIRBY, M.H. (Master of Hulkability) Art: BILL EVERETT, B.H. (Bachelor of Hulkosity) Lettering: ARTIE SIMEK, P.H. (The Pride of Hulkdom)

Lee’s public persona was perpetually enthusiastic about Marvel’s readers, as well. To read Marvel’s comics, he insisted, was to be part of a cultural moment: he addressed readers as “effendi,“ “frantic ones,” “true believers.” The grandiosity of Lee’s tone was a gag, and one his audience was in on. He could shift from pomp to self-mockery in a heartbeat, as on the cover of 1964’s X-Men #8: “Never have the X-Men fought a foe as unstoppable as Unus! Never have the X-Men come so close to being split up! (And never have you read such a boastful blurb!)” When readers started pointing out errors in Marvel’s stories, he invented something better than a prize: the “no-prize,” awarded to fans who could explain why an apparent mistake wasn’t really a mistake. (The “no-prize” was an ornate envelope with nothing inside it.) Pumping up readers’ egos was a great way to part them from their money, but Lee’s fake chumminess wasn’t just flimflammery: even if the “bullpen” where Marvel’s creators all hung out together didn’t really exist, he did loop eager readers into a real community. Read the letter columns of 60s Marvel comics, and you’ll find missives from a who’s who of future comic-book stars (enthusiastic correspondents Roy Thomas, Marv Wolfman, and Jim Shooter all went on to serve as Marvel’s editors in chief) and pop-culture icons. Young George R. Martin, for example—who had yet to add the second “R” to his initials—wrote a fan letter printed in 1963’s Fantastic Four No.20: “I cannot fathom how you could fit so much action into so few pages.” None of that had much to do with Lee’s actual scriptwriting, which would never pass muster by most modern standards. Word balloons and expository narration clog every page of his comics; everyone seems to be hammily speechifying all the time. The voice of Lee’s omniscient captions is weirdly overfamiliar, like a seatmate on a train who’s about to pitch you a timeshare. Then again: I’m currently writing a book about reading all 27,000 Marvel superhero comics, and the more time I’ve spent looking at Lee’s language, the more I’ve come to admire and linger over it. It’s overwrought, over the top, in love with its own cleverness—and why shouldn’t it be? Anyone could have called the force that the Silver Surfer commands “cosmic power.” It took Lee, with his ear for grandiose, poetic speech, to invert that to “the Power Cosmic.” (Unless Kirby came up with that bit—though it sounds a lot more like Lee’s diction.) Similarly, it’s not clear whose idea it was to recast Shakespeare’s Sir John Falstaff as a Norse warrior god—Lee and Kirby both claimed that honor—but The Mighty Thor’s Volstagg the Voluminous is, in any case, a great supporting character, an enormous, over-the-hill warrior who talks a bold game despite his blatant cowardice, and manages to keep coming out on top by sheer accident. Lee’s voice for him is note-perfect: when Thor starts helping Volstagg break out of a stone cage, he indignantly replies, “How now?!! To speak so of giving aid to Volstagg is akin to giving the peacock an extra feather . . . the porcupine an extra quill!” In Marvel’s 60s comics, there’s some delicious Lee-ism every few pages, a turn of phrase none of his contemporaries could have approached:

“Hah! Most truly thou art oafs and bumblers all! Thy swords should sing a symphony of slashing, savage steel! But blunted are thy blades—and timorous thy thrusts!” “Once again your decadent capitalistic innocence has betrayed you!” “All right, you sawed-off spineless slinkin’ slobs! Stop that fightin’ afore I lose muh temper! This is Sheriff Iron-John McGraw talkin’ at yuh!” “Enough!! None speaks thus in the presence of Dormammu!” “There was no point in telling her that my dad is so rich he hardly ever pays taxes! He just asks the government how much it needs!” “Now, where cajolery has failed—let carnage succeed!”

Who talks like that? Nobody. Nobody looks like a Jack Kirby character, either. Neither Lee nor Kirby was interested in “realism” except as a way to anchor the stylistic flourishes of their work. Of course practically every line of Lee’s scripts ended in an exclamation point: if the excitement let up for a single page, that would have been a betrayal of his readers. In 1972, Lee gave up the monthly comics-writing game almost altogether. He came back to Marvel’s pages for special occasions—writing the occasional Silver Surfer story or dialoguing a backup story for old times’ sake in an anniversary issue—but the only time he wrote more than two consecutive complete issues of a Marvel series in his last 46 years was 1992’s dreadful Ravage 2099, on which he stuck around for six months before slinking out the back. Lee became Marvel’s jovial spokesman on tv, the cheerful old man trotted out to sign back issues and pose for pictures at conventions, the perpetual credit on the daily Spider-Man newspaper strip (by all accounts, he did write its dialogue), the jokester who turned up for a quick gag in every Marvel movie. And he never did write that “Great American Novel”; he never wrote a prose novel at all. The comics he scripted weren’t intended to be a grand statement on the American condition. To the extent that they were one anyway, they did it by accident. Stan Lee has three avatars in the Marvel story. The first one is “Stan Lee,” the omniscient narrator of hundreds of stories, telling them with his signature sly oratorical grandeur and his tumbling Old Bronx accent. Even the comics he never laid eyes on are “presented” by him. They implicitly have his approval. The second is Uatu, the Watcher—Lee’s on-screen role in “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2,” more or less. Uatu lives on the Moon, and belongs to an ancient race that observes everything but is not supposed to intervene in other species’ affairs—though Uatu has been known to subtly steer events. The third is Loki, the god of lies, or mischief, or fiction, or all three. Loki is silver-tongued and vainglorious, and always has a worthwhile aim in mind, or is at least glib enough to claim so convincingly. He prefers to nudge people in the direction of accomplishing his goals, rather than doing the difficult work himself. He makes his younger successors swallow the lies he’s created, and reaps the benefits of their good works. Yet it’s difficult to hate him entirely. He doesn’t bring the Avengers into being individually, but he brings them together. He argues that nothing good in his world would be as it is without him, which isn’t wrong. He’s a con man, but he does deliver.

***

JUST AS THE AURA WAS EVAPORATING around the news of Stan Lee’s death, iconoclastic comedian Bill Maher chanced onto the scene, creating a furor all his own. In his blog several days after Stan’s death, Maher composed a short piece that claimed Stan Lee is partly to blame for the dumbing down of America. Here it is, all of it—: The guy who created Spider-Man and the Hulk has died, and America is in mourning. Deep, deep mourning for a man who inspired millions to, I don’t know, watch a movie, I guess. Someone on Reddit posted, “I'm so incredibly grateful I lived in a world that included Stan Lee.” Personally, I’m grateful I lived in a world that included oxygen and trees, but to each his own. Now, I have nothing against comic books – I read them now and then when I was a kid and I was all out of Hardy Boys. But the assumption everyone had back then, both the adults and the kids, was that comics were for kids, and when you grew up you moved on to big-boy books without the pictures. But then twenty years or so ago, something happened – adults decided they didn’t have to give up kid stuff. And so they pretended comic books were actually sophisticated literature. And because America has over 4,500 colleges – which means we need more professors than we have smart people – some dumb people got to be professors by writing theses with titles like Otherness and Heterodoxy in the Silver Surfer. And now when adults are forced to do grown-up things like buy auto insurance, they call it “adulting,” and act like it’s some giant struggle. I’m not saying we’ve necessarily gotten stupider. The average Joe is smarter in a lot of ways than he was in, say, the 1940s, when a big night out was a Three Stooges short and a Carmen Miranda musical. The problem is, we’re using our smarts on stupid stuff. I don’t think it’s a huge stretch to suggest that Donald Trump could only get elected in a country that thinks comic books are important. Maher terminus. RCH—: I’m a big Maher fan and wouldn’t miss his weekly telecast on HBO every Friday night. But I think he makes a mistake here by assuming that comic book fans think they’re reading great literature. Most of us think of comic books as entertainment. And if Maher thinks we’d be better off without entertainment, then I suppose he ought, in good conscience, to retire to the Old Comedians Home. The response from fandom and friends of Ol’ Stan was instantaneous. And voluminous. How dare Maher mock Stan Lee and belittle what he’d done? Lee’s POW! Entertainment company issued a statement: “Mr. Maher: Comic books, like all literature, are storytelling devices. When written well by great creators such as Stan Lee, they make us feel, make us think and teach us lessons that hopefully make us better human beings. One lesson Stan taught so many of us was tolerance and respect, and thanks to that message, we are grateful that we can say you have a right to your opinion that comics are childish and unsophisticated. Many said the same about Dickens, Steinbeck, Melville and even Shakespeare. “But to say that Stan merely inspired people to ‘watch a movie’ is in our opinion frankly disgusting. Countless people can attest to how Stan inspired them to read, taught them that the world is not made up of absolutes, that heroes can have flaws and even villains can show humanity within their souls. He gave us the X-Men, Black Panther, Spider-Man and many other heroes and stories that offered hope to those who felt different and bullied while inspiring countless to be creative and dream of great things to come.” I’m not sure I’d agree that any of the works of Dickens, Steinbeck, Melville or Shakespeare were called “childish” or “unsophisticated.” They may have been mostly ignored until the next generation. But Maher proved capable of responding to the backlash on his own, which he did while a guest on “Larry King Live.” He said he didn’t know people were mad because he “doesn’t follow every stupid thing people lose their shit about” on social media. “But talk about making my point for me: Yeah, I don’t know very much about Stan Lee, and it certainly wasn’t a swipe at Stan Lee.” King interjected: “You would have liked him. He was a really nice guy.” Maher continued: “Yeah, fine. I am agnostic on Stan lee. I don’t read comic books. I didn’t even read them when I was a child. [Initially, remember, he said he did.—RCH] What I was saying is, a culture that thinks that comic books and comic book movies are profound meditations on the human condition is a dumb fucking culture. And for people to get mad at that just proves my point.” Neil Gaimen, the most civilized of the responders, wrote: “Maher’s just trolling, and lots of people are rising to the troll. (Julie Burchill did it better 30 years ago with her ‘There aren’t any adult comics because adults don’t read comics’ line. ) More people cared about Stan Lee’s death than care about Bill Maher alive.” I suspect Maher’s initial online blurt was prompted not by Stan Lee per se but by the plethora—the excessive outpouring of grief and acclaim that littered the news and social media for days after Stan Lee’s death. It was a little much, kimo sabe. But it is a measure of Stan Lee’s influence and impact on the comic book industry that so many people felt compelled to say something, usually something nice. I fell victim to the same impulse, as you see. Stan Lee was Somebody. And while we maybe won’t miss him much—after all, his hand on the tiller at Marvel comics disappeared fifty years ago—we would have missed him a lot if he had chosen another way to make money. What if there had been no Stan Lee, as Rick Marschall posits. We’d be the poorer for it. If you need to make a nasty response to Maher, Gaimen’s is about as civilized as we can expect. Me? Well, I derive pleasure from Maher’s wit, regardless of what he says. And in this case—assuming he’s reacting to the plethora—I agree with most of what he says.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |