|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 372 (October 22, 2017). Herewith, we drop the other shoe. Opus 371, which we posted just days ago, was the first half of a posting that grew so verbose and lengthy that it broke in half. This is the other half. Opus 371 was mostly news; Opus 372, the one you’re poised to read, is mostly reviews— of first issue funnybooks, cartoons in Esquire, and books on Mort Meskin and Jerry Robinson, Rube Goldberg’s Foolish Questions and Shoe comic strip reprints, plus graphic novels Baker Street Four (Vol.2) and Corto Maltese in Siberia. But there are other topics—where ideas come from, Hank Ketcham’s scarred visage, “line tangent” explained, lampooning at the National Cartoonists Society, what’s happening in newspaper comics, and obits for Len Wein and the Summer of Love. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Seuss Museum Brouhaha Marston Menage a Troi Creates Wonder Woman Movie Garfield Galactus Phoenix Rises Bettie’s Back

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of First Issues Of—: Dastard & Muttley HeroKillers James Bond: Moneypenny The Hard Place Trump’s Titans Sheena Queen of the Jungle And follow-up on—: Divided States of Hysteria Shirtless Bear-Killer Jimmy’s Bastards Normandy Gold Shipwreck

WHERE DO IDEAS COME FROM? An Essay on the Creative Process

TRUMPERY By Garry Trudeau (Illustrated)

EDITOONERY A Few of the Recent Crop THE FROTH ESTATE A Quotable Quote

CARTOONING IN ESQUIRE Analysis & Critique

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL What’s Happenin’ Plus a Book Review of the new Shoe Reprint

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Hank Ketcham’s Self-caricature and How It Got That Way

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Reviewing Older (but not Antique) Books—: From Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin RANCID RAVES GALLERY Shannon Wheeler’s book of Trump Tweets Verboten “Line Tangent” Explained and Illustrated Spots of the Trumpet

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: Foolish Questions & Other Odd Observations: Early Comics by Rube Goldberg Jerry and the Joker: Adventures and Comic Art by Jerry Robinson A Round-up of Forthcoming Titles Encyclopedia of Black Comics (alert)

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Reviews of Graphic Novels—: The Baker Street Four, Vol.2 Corto Maltese in Siberia

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Lampooning at National Cartoonists Society

PASSIN’ THROUGH Obit for Len Wein Remembering the Death of the Summer of Love (And Where Was I Then?)

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of the News That Gives Us Fits

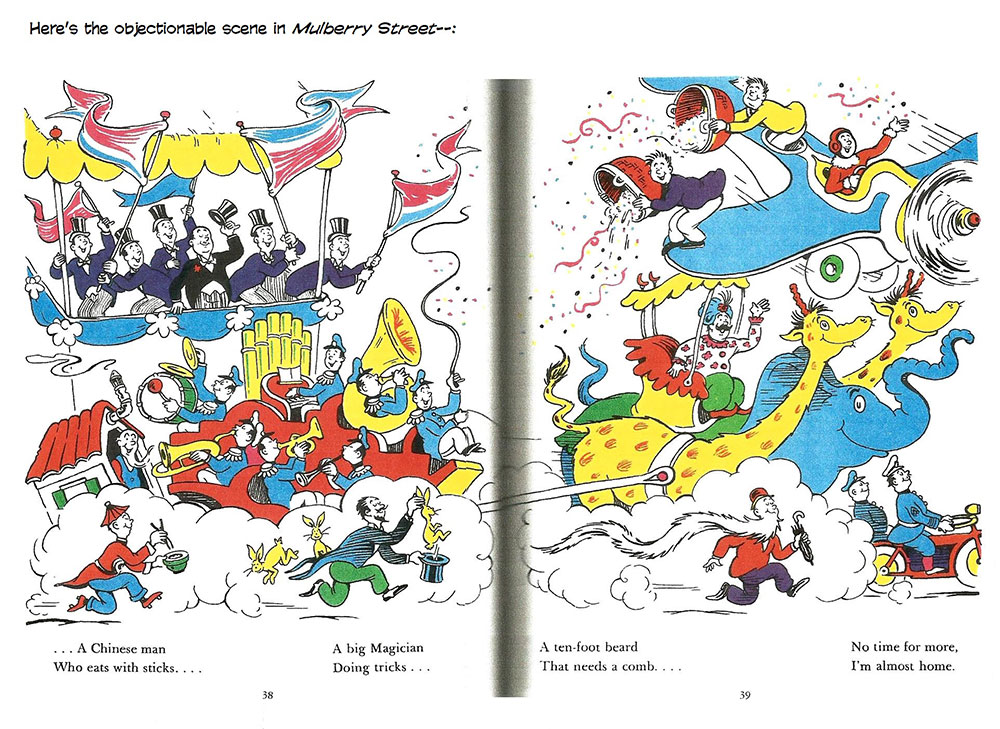

PRISSINESS WINS The PC

horseshit about a mural at the Seuss Museum (reported last time, Opus

371)—which, taken from an illustration in Dr. Seuss’ 1937 Mulberry Street book,

depicts a Chinese man with slanted eyes, a pointy hat, eating with chopsticks,

and wearing clogs—resulted in the Museum removing the mural. As I said last time, I don’t like this fuss because it is wholly wrong-headed. Its only redeeming aspect is that it proves the folly of Political Correctness. What’s correct to some people is incorrect to others. Some people objected to the Museum’s failure to exhibit Seuss’s racist political cartoons from World War II, when nearly all editoonists were making racist caricatures of Japanese and Germans, because Seuss’s racism in those years was part of his personality and therefore ought to be in the Museum; and others, the three authors f’instance, objected to what they saw as a racist picture of a Chinese man and wanted it removed. So: make up your minds! Racism or no racism—which is it to be? The contradictory impulses here were what got my wattles in an uproar, demonstrating, as they do, how silly the PC preoccupation often is. (Not always, but usually.) The authors, in their protest, thought the Museum should created a “context” for the Chinese man picture so it would be a “teachable moment.” Context? What the hell is the “context”? That everyone was a racist 100 years ago (and not so long ago as that, even)? And that everyone still is? I suppose. But the Chinese man with chopsticks doesn’t strike me as a racist portrait. It seems a stereotypical incorporation of widely-recognized cultural attributes into a single picture—much like picturing an Indian with a moustache and a turban, riding on an elephant, which also occurs in the mural. If Seuss had wanted a representative of Africa, I suppose that representative would be colored brown or black. Is that racism? So how should Seuss have depicted someone he wanted to be representative of China? Of India?

THE MANAGE A TROI ORIGIN OF WONDER WOMAN The creation of Wonder Woman by a man living in the same household with two women who were also his sexual partners (on alternate nights?) is simply too juicy for Hollywood to pass up. And so writer/director Angela Robinson made a movie of it, making, now, common knowledge what only funnybook fans have known (and they only for a couple dozen years)—namely, that the inventor of Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston, lived with his wife, Elizabeth Marston, and his lover, a one-time student of his, Olive Byrne, in a happy, lasting menage a troi. The arrival of the film has provoked no little comment and amazement among film critics and reviewers. One of the best is in thecomicsjournal.com, where Tim Hanley begins with this insightful description—: “In a pivotal scene in Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, Olive Byrne (Bella Heathcote) dons a burlesque outfit in a shop run by Charles Guyette (JJ Field), a man known to history as the godfather of American fetish art. Robinson’s film is the story of Wonder Woman creator William Moulton Marston (Luke Evans) and his polyamorous relationship with Elizabeth Marston (Rebecca Hall) and Olive, and this scene is key to the genesis of the famed heroine. Along with the skimpy outfit, Olive wears a tiara and large bracelets, and she holds a golden rope. While the costume itself is dark, there’s gold along the chest and red and blue lights reflect off the shiny black material; the backlighting creates a recognizably iconic silhouette. William looks on with awe and lust as Elizabeth ties up Olive in the sturdy rope, and the film then immediately cuts to him at home writing ‘Suprema the Wonder Woman’ in a notebook. “It is a sensual, compelling scene, and an important moment for all three leads. It is also entirely fictional. “On its own terms, Professor Marston and the Wonder Women is a very good film indeed. It begins in the mid-1920s when married psychologists William and Elizabeth encounter Olive, a student of theirs at Radcliffe College, and follows the evolution of their relationship from intrigue to lust to love. After initial trepidation, the three form a family, with each woman having two children via William. Inspired by these remarkable women, William creates Wonder Woman in 1941, and the film ends in the mid-1940s, shortly before his death. It’s an unconventional love story, and Robinson treats both the polyamorous and BDSM [bondage, dominance, sadomasochism] aspects of the relationship with respect and care. The film is sexy without being exploitative, romantic yet frank, and often boldly raw as it delves into the emotional complications of the Marstons’ life together.” The film, Hanley goes on “is a captivating piece, but it’s also a biographical sketch that claims to be ‘the true story of the women behind the man behind the Woman,’ and this is where matters get complicated. It’s a good story well told, but is it the Marstons’ story? All biopics play fast and loose with history, changing details for the sake of simplicity or additional conflict. Creative liberties are to be expected. But at the same time, one also expects a certain level of knowledge and insight into the subjects, their lives, and the world in which they lived.” The movie makes some changes to the history it purports to relate, some minor, some not. The pivotal role of Sheldon Mayer, an editor at All American Comics, who deleted “Suprema” from the name of Wonder Woman, is omitted from the story. And the role of Josette Frank, a member of the company’s advisory board, is elevated. And the chronology is adjusted to make a more straight-forward narrative. But, Hanley says, we don’t know if Elizabeth and Olive were into bondage—or, even, if they were romantic or sexually involved. Robinson opts for both. “We don’t know,” Hanley sayd, “because we can’t know. The Marstons were very private people, and details about their life together are few. Their descendants are on the record stating that Elizabeth and Olive were like sisters, there was no sexual relationship between them, and there were no bondage activities in their home. Now, the women may not have been inclined to share such information with their children and grandchildren, but there is no definitive information to counter the family’s claims either. “There are reasons to speculate. William wrote at length about ‘female love relationships’ in his psychological work, heartily endorsing sexual activity between women. And, as the film points out, Elizabeth and Olive lived together for almost forty years after he died. That is the most that we’ve got. With the bondage, a close reading of Wonder Woman and William’s other work does suggest a fetishistic preoccupation with such imagery on his part, but again, that’s all we know. There’s no evidence that he engaged in such activities himself, or that either woman was at all interested in it. “What we do know is that, while married to Elizabeth, William began a relationship with Olive and she eventually joined their home. Sources differ on how this came together; some suggest that Olive was happily welcomed by Elizabeth, others say that there was friction over the matter.” Some speculate that Elizabeth welcomed Olive because she saw that the arrival of the younger woman solved a problem for her, Elizabeth. She wanted a family and a professional life; Olive seemed a candidate for live-in baby-sitter, which would enable Elizabeth to have children but to still be free of domestic obligations. Hanley continues: “ Regardless, Marston had two children with each woman. While this tells us that he had a romantic and sexual relationship with each woman, we remain fully in the dark about Elizabeth and Olive’s connection beyond sharing William. “Robinson ignores this established information in Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, and centers the development of their triad on Elizabeth and Olive. While William is attracted to Olive from the start, the women are the key players here. Olive falls in love with Elizabeth first, and kisses her early on. Elizabeth doesn’t return her affection originally, then when she finally does, it’s the two of them who initiate the trio’s first sexual encounter. William just shows up after to join in. The women begin the bondage play in a similar manner: William is intrigued with it to start, but it’s Olive who chooses to don the tight burlesque outfit and Elizabeth who ties her up. While William ends up with all his fantasies fulfilled, it’s only because Elizabeth and Olive are drawn to each other and let him in on it. “The mysteries of the Marstons’ home life invite speculation. With so few established facts, reading between the lines is inevitable. Robinson goes a step further, not only presuming that the two women had a romantic relationship but also ignoring the few known facts about how the family came together to center them as the trio’s driving force. It’s a storytelling choice that is unsubstantiated and at odds with history, and calls into question the film’s claim to be the ‘true story’ of the family. These decisions go beyond speculation into outright fiction.” Robinson also leaves out of her film the role the two women played in the creation of Wonder Woman. Marston, inspired by the burlesque bondage at Guyette’s, concocts “Suprema” and goes off to sell his idea to Max Gaines, the publisher at All American Comics. Not exactly, saith Hanley. “While William did meet with Gaines to present his comic book idea, this meeting came about because of an article written by Olive for Family Circle. Olive regularly wrote up interviews with William for the magazine, and one in which he praised the potential of the comic book industry caught Gaines’ eye. He reached out to William, who ended up pitching him a new heroine, and this was because of Elizabeth. Originally, William was thinking about a male hero who would showcase the benefits of submitting to the loving authority of woman, but Elizabeth declared, ‘Come on, let’s have a Superwoman! There’s too many men out there.’ Without Elizabeth or Olive, Wonder Woman would never have existed. “Moreover, both women had spent the past decade keeping William afloat. The film shows how the family’s unconventional lifestyle led to him being blacklisted in academia, but it glosses over his many failures throughout the 1930s. Before Wonder Woman, William had mounted countless endeavors, including psychological texts, a novel and advice books, Hollywood consulting, using the lie detector in advertising, and more. None succeeded. Elizabeth kept the family fed and clothed with her steady job, and Olive contributed by writing articles and running the household. After years of both women running the household while William flitted from idea to idea, he finally landed a steady gig with Wonder Woman. “On several fronts, Wonder Woman was the product of the entire triumvirate, not just William, and to reduce Elizabeth and Olive’s role to nothing more than inspiration is a disservice to both women. It also takes us further from the ‘true story’ yet again, and ultimately Professor Marston and the Wonder Women fails as an accurate account of the Marstons and the creation of Wonder Woman. “It’s a well-made film with charismatic leads, and there’s much to recommend it, including a thoughtful depiction of polyamory and queer romance. But while the broad strokes of the story loosely resemble the truth, the litany of speculation, invention, dismissal of established details, and changes big and small add up to far more fiction than fact.” I told you Hollywood couldn’t resist.

GARFIELD GALACTUS Galactus as envisioned by Jim Davis’ Garfield will make an appearance in Marvel’s Unbeatable Squirrel Girl No.26, out in November. Yes, that’s right: the fat orange cat enters the universe of superheroes. This issue of the Girl, said Christian Holub at ew.com, “will be styled as a zine made by Squirrel Girl and her super-powered peers, with different artists providing styles for different heroes-turned-artists.” Writer Ryan North contacted Davis to do one of the features. Galactus seemed to Davis like a logical choice for Garfield to produce because Galactus is big and has an appetite rivaling Garfield’s: Galactus, remember, eats planets whole. North wrote the story which Davis illustrated with the customary help of his assistants Gary Barker and Dan Davis. “The strip basically uses Galactus as a stand-in for Garfield and his herald the Silver Surfer as a stand-in for Jon Arbuckle,” Garfield’s hapless so-called master. Said Davis: “When you look at the Silver Surfer, he’s 75% of the way there with Jon, all we had to do is give him the big eyes. That was a natural. Jon kind of hangs around Garfield anyway: he’s the straight man to Garfield’s gags and has to get him food. He’s like Garfield’s herald. “Galactus was tougher,” Davis went on. “We were throwing stuff back and forth, and the initial sketches just weren’t working for Galactus. I said, Okay—we gotta make him fat. The guy eats planets, for godsake! Once we did that, it’s a little less Galactus but certainly a lot more Garfield. It looked more natural. Obviously, Galactus has put on a few mega-tons for this issue.”

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

DASTARD & MUTTLEY is about a couple of contemporary pilots. The first part of the first issue flaunts entirely too many pictures of aerodynamically superior airplanes; nothing about a picture of an airplane, no matter how superior its aerodynamics, is inherently interesting. Bad comics. The pilots’re flying a reconnaissance mission in the wake of some sort of immense explosion. In the first seat is Richard “Dick” Atcherly, seconded by “Mutt” Muller, who, unaccountably, has brought his pet dog along. Most of their time is spent arguing about the dog. Then they’re approached by a mysterious drone, spewing some sort of orange gas. The plane is disabled, the pilots eject, and the plane crashes. Next, we’re in a hospital as Atcherly recovers consciousness. He’s being debriefed by a couple of obnoxious FBI types (who refuse to say what agency they are from) whose aggressive questions are matched by Atcherly’s aggressive non-responses. He wants to know where Muller is. He’s somewhere else, they say. They leave, and Atcherly doses off. When he awakens, it’s dark, and Muller is in the room. When he steps out of the shadows, we see that he has the face and head of his dog. So that’s the cliffhanger.

It’s Garth Ennis’s story and it brims with his usual unconventional concepts. Mauricet, who has no first or last name, draws the pictures, and his style is crisp and pleasing, albeit a little sterile. The storytelling makes good use of varied page layouts and panel compositions. Visually speaking, the book is a thoroughly competent work. But the story—apart from the mysterious dog-head thing—doesn’t grip me.

THE INITIATING PREMISE in HeroKillers No.1 is that when crime-ridden Libertyville elected a new, fabulously wealthy mayor, hizoner offered to pay superheroes fabulous amounts of money to rid the town of crime. The heroes soon outnumbered the criminals four-to-one, and crime was busted out of the city. Now the crime-free town has a lot of superheroes trundling around without crime to fight. So they pick fights with robots and compete among themselves for whatever rewards and fame are available. In other words, the story, by Ryan Browne, mocks the conventions of superheroing, deploying some of yesterday’s unemployed superheroes—Captain Battle and Captain Battle Junior, the Boy King and his Magical Giant, and, most memorable to me, personally, and to the plot of this issue, Black Terror and his youthful sidekick, Tim. In the book’s first completed episode, Black Terror turns out to be an alcoholic egomaniac, eager to collect all the glory himself. In the next completed episode, the sidekicks manage to crime-bust the evil Dr. Baron Von Physics, and then Black Terror shows up and shoves the youngsters away from the crime scene so he can get all the credit when the news media show up. At the last moment, however, Tim disintegrates his mentor, and he and his two companions, both sidekicks of other superheroes, fabricate a scenario to explain Black Terror’s seeming death. This is a lot of fun, but I can’t tell where it’s going. Are the sidekicks now going to take over the world? That doesn’t seem sufficiently admirable, but, given the book’s title (“Hero Killers”), it seems entirely likely. Pete Woods’ art is crisp and uncluttered, so uncluttered that there isn’t much in the way of background. The visuals are nearly antiseptic. But he’s a master of anatomy and facial expression and deploys page layout and panel composition to keep things lively. Still, despite my affection for Black Terror (a residual of my misspent youth, whiling away hours with funnybooks), I’m not likely to return to this title.

JAMES BOND:

MONEYPENNY is a

one-shot starring M’s receptionist with whom Bond often flirts. Written by Jody

Houser and cleanly,

WORKING WITH A SOMEWHAT CLICHE SITUATION, writer Doug Wagner manages a nifty twist and sucks me in with The Hard Place, No.1. A.J. Gurney gets out of prison after five years and vows to go straight hereafter. In one episode complete in a few pages, he visits the local brutal crime boss to make sure he’ll be left alone to pursue a useful civilian life, working with his father in an auto repair shop. We witness several brief but complete episodes that demonstrate the extent of Gurney’s resolve—including one in which he declines a chance to drive a souped-up cop car despite his being the best driver in Detroit. In the book’s final episode, Gurney dresses up in a suit and tie in order to enhance his chances of getting a loan at the bank—a loan essential to revitalize his father’s business. The bank’s loan officer is just about to grant Gurney’s request when two robbers enter the bank. Gurney encourages the loan officer to call 911, and when one of the robbers sees what’s going on, he shots and kills the guy. The robber also recognizes Gurney, “the best wheelman money could buy,” and as the book ends, Gurney is being recruited to unwillingly drive the robbers’ getaway car as depicted in the foregoing visual aid. The story moves inexorably, step by illuminating step, to its inevitable conclusion. Nicely done. The tale builds to the twist that ends it for now. It begins on the first page by depicting the results of an auto accident, and half-way through the book, we witness the inside of the speeding car that eventually crashes, killing an occupant. When we get to the last page, then, we’re ready to draw a conclusion. The dead guy in the car wreck doesn’t look like Gurney. The next issue, which I’m sure to get, will tell us whether we’re right. (Well, not quite: new mysteries and dilemmas abound in No.2—enough to keep me going and going and going.) Nic Rummel’s artwork is distinctive with a capital B. He deploys the boldest line I’ve seen in comics in years. And he decorates some of the space between the lines that outline faces with quirky thinner lines that model the portraits.

IN A SPOOF OF OUR CURRENT PREZ, Trump’s Titans stars the Trumpet with a much better-looking hair-do. Herein, the Trumpet and Veep Mike Pence, Steve Bannon, and Jared Kushner—all the president’s men, you might say—get a dose of superpowers. “The President has been given all powers that exist,” Kushner explains, “—because he’s President. The rest of us each have one power.”

This book is written by John Barron, not a Trump fan, and drawn by Shawn Remulac, who manages workable likenesses of the principal characters in his clean style. Fun stuff that exists solely because our current Prez is such a comic book character.

THE FIRST ISSUE

of Sheena Queen of the Jungle, a revival title, exists mostly to give Moritat a chance to draw the sumptuous Sheena in as many different poses in her

scanty leopard-skin costume as he can devise. He is aided and abetted by

writers Marguerite Bennett and Christina Trujillo who supply a

tale in No.0 so simple that only Mortat’s pictures make it memorable. The plot,

so to speak, is that Sheena, sworn protector of her forest, sees a flying

saucer (or something like one, but small, not large enough to have passengers)

and takes steps to prevent its And then we get the last page: no longer in the jungle, we see a young man looking at his computer screen, eating spaghetti and saying, “What did I just record?” That might bring me back. Moritat’s drawings definitely will.But in the second issue, No.1, all we have are more pin-ups of Sheena. No outright nudity, though: these pictures could have survived quite well in the repressive 1940s. The story is about as vacuous as the one in No.0. I’ve had enough.

TIDYING UP. Howard Chaykin is up to the fourth issue of his The Divided States of Hysteria. This issue concentrates on flinging around as many racial and sexual verbal slurs as possible—spics, kikes, faggot, dick, yid, etc. This maneuver is probably intended to give the tale an aura of nasty reality; maybe so, but some realities aren’t at all appetizing or gratifying. Chaykin doubtless thinks he can get away with all this because he’s a Jew, but it’s just a little stomach-turning. The plot, such as it is—a bunch of career criminals being trained to help save the world— makes a little progress, but Chaykin’s new drawing mannerisms result in an unappealing book: every panel is decorated with some sort of faded lettering, running across the top like the unending drone of a machine (but we can’t make out the words; no clue here), and the human figures are often too small, nearly lost in the imported computer-generated imagery that he uses for backgrounds. Last

time, I mentioned a memorable scene in Shirtless Bear-Fighter No.3 in

which we are treated to a sequence in which the villain takes a crap in a gold

toilet. I was seriously remiss in not posting that memorable sequence. Here, I

correct my dereliction. Logger sets a passel of loggers loose in the forest, but they’re frustrated by some combatant bears. Says one logger: “Can’t believe we quit our jobs as comic book editors for this.” Without an editor, no wonder the book seems shapeless. Occasionally funny but shapeless.

THE THIRD ISSUE of Jimmy’s Bastards is better than the previous issue. Herein we get some snappy banter as Jimmy and his black female assistant (who is determined not to succumb to Jimmy’s charms) fight some bad guys in a museum. Now we’re having some fun. Phil Hester’s art continues to be spectacular in the fifth issue of Shipwreck. And in the third issue of Normandy Gold, Normandy, in her guise as a hooker, is drugged and raped by a guy she’s come to investigate/fornicate. Later, she comes back and kills him messily with a knife, but when she returns to the scene of the crime with another cop, neither body nor blood stains can be found. Dunno anymore where this title is going, but Steve Scott (pencils) and Rodney Ramos (inks) betray here a fondness for rendering the female form in naked glory. (Sorry: that’s a terrible expression.)

WHERE DO IDEAS COME FROM? One of the most-frequently asked questions of cartoonists is: Where do you get your ideas? Whenever I’m asked (which, these days, isn’t often), I say, “Schenectady” (stealing this response from some antique wag). Dan Piraro of Bizarro fame once told a roomful of fans that he didn’t worry about getting ideas. When his Bizarro was accepted for syndication, he explained, he immediately sat down and wrote out ideas for the next 25 years. I recently attended a lecture by a former correspondent, Disney Legendary animator, Floyd Norman, and when he was asked the question he said that he got ideas by listening to the characters he was drawing. As he drew them, they began to talk and cavort around in his imagination, and he listened to them, and eventually, sure enough, he’d get an idea for a cartoon. Charles Schulz, when I ask him, said basically the same thing. He started doodling characters, and they started “talking” to him. I remember having the same experiences when I was sketching character designs for my numerous unsuccessful comic strips. As I sketched, the characters took shape in my imagination and often took off running in directions they opted for themselves, without any prompting from me.

For some odd reason, whichever character I was designing as the protagonist of a strip eventually wound up sitting at and playing a piano. None of them were piano players. But there they were at the keyboard. So I know that ideas occur to me when I’m drawing, too. Not just when I’m drawing: I have ideas at other times, too. But when I’m drawing, they pop up. And here’s an example—: A

few weeks ago, I was asked to illustrate a promotional flyer for a project that

was not only a “win-win” project but a “win-win-win” project. I chose the

“wins” as the basis for the illustration, and drew three giant-lettered “wins,”

stacked across the page as you see near here. Then I thought I should do something to make it cartoony. I should give the letters some kind of personality. I gave the ‘W’ in the first “win” legs and eyes and a smiley mouth. A happy ‘W.’ Then I moved on to the second “win,” deciding, en route, that I’d embellish the ‘I’ rather than the second ‘W.’ At first, I thought I’d do the same thing as I’d already done. Then in doing it, I varied it, giving this letter squinty, happy eyes. And I reversed the legs, letting him put his left leg forward. Next,

the ‘N’ in the last “win.” Legs again reversed from the previous drawing. But

how to vary the rest? Ha—open his As a progression, the “wins” get happier and happier. Good thing for “win-win-win.” The point is: each stage in the development of the drawing proceeded from the previous stage, each fostering the next variation. Ideas from drawing. In then final, finished version, I added some shading to the letters to set them apart a little from the all-white plain background. Then to finish it off, I drew the little guy in the corner, hugging his legs and grinning—no loser he.

QUOTES & MOTS “Eighty percent of evangelical Christians who cast ballots in November 2016 voted for the man [the Trumpet], who seems as far from Christian virtues (humility, kindness, patience, etc.) as Hulk Hogan is from the Dalai Lama. These are people who pray for guidance. So apparently Jesus got the story wrong. The rich man came to Lazarus who was covered with sores and asked for a tax break, and the rich man was rewarded and Lazarus went to hell. Do unto others as you are glad they don’t have the means to do unto you.”—Garrison Kiellor

TRUMPERY By Garry Trudeau Donald Trump is obviously sui generis in every way—not least for me because I actually draw him. I used to let the reader do the work, depicting public figures as off-stage voices, then icons, but from the beginning, Trump was an exception. I’ve been drawing him in traditional caricature for 30 years, mostly because I wanted him as an actual cast member—a foil for Duke and the other characters. Also, his face, with piggy eyes and curling, contemptuous lip, was irresistible. I never settled into just one look for him. I started each caricature from scratch, and as his brown hair turned into lacquered panels of gold and his jowls melted over his collar, there was new fun to be had with every passing year. So representing Trump isn’t easier or harder for me than Nixon or other presidents, just different. But what has really mesmerized me over

the years was not the visual wreck he presented, but the chaos he created wherever he turned. A born salesman with a working vocabulary of 600 words, most of them insulting, Trump used language for selfish, often evil, ends more effectively than any public figure in our lifetimes. He represented everything reprehensible about the broader culture, the dark side of the American Dream. Which, of course, put him right in the wheelhouse of Big Comedy! We’ll be forever in his debt.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WE EXPLORED THIS ASPECT OF CIVILIZATION at great length last time, and you’d think that’s sufficient. “Last time,” after all, was only a week or so ago. How much more can have happened that deserves our mockery? And then came Harvey Weinstein. Harvey Weinstein was exposed, for all the world to see (which is probably how he likes it), as a sex maniac. What else do we call a man who gets his sexual jollies out of having a woman watch him masturbate? Weinstein is undoubtedly one of those males whose dick assumes a much larger dimension in his imagination than it actually occupies in life itself. His penis is himself incarnate, so to speak. His sexual self. This is serious stuff. And certainly, penises are no laughing matter. Everyone knows that. Women learn it at their mother’s knee and other lowly joints: whatever you do, do not giggle and point at your man’s penis. Particularly the aroused version. The erect penis is maleness incarnate, the male ego rampant. Penis equals man. Size, therefore, matters. But only to the male ego. Even though the word penis is itself humorous, the anatomical appendages are not supposed to be funny. But they are: just look at them. A famous lady with vast experience is reported as saying, “If I had that dangly thing between my legs, I’d laugh all day.” No, I don’t remember who said it. Probably Tallulah Bankhead. Sounds like something she’d say. And she was famous and experienced, so she ought to know. When not dangling, when, instead, getting ready to do the deed for which they’re designed, penises are even more laughable. They’re not, actually, erect. The term itself is contradictory: penises are not erect—their stiffness is horizontal, perpendicular to the vertical male body. The male body is what’s erect. The perpendicularity is comical, creating an incongruity in an otherwise vertical dimension. At such hilarious moments, the male ego is all wrapped up in a visual joke. Ha. By the same quirk in so-called reasoning, female anatomy is scarcely the symphony of curves we’ve all heard about. Objectively—aesthetically—considered, women’s bodies are lumpy, assembled of cobbled-up bulges. Penises are undeniably risible (pun unintended but relished nonetheless), but we are still not supposed to laugh at them. Mothers recognize this eternal and immutable truth, and they caution their daughters about it: on the morning of the daughter’s wedding day, mothers tell them not to laugh at their husband’s penis on their wedding night. Laughter at this crucial moment can destroy a marriage before it even gets going. That’s because, like Harvey Weinstein, we get ourselves too wrapped up in our penises. They become our sexual selves, as I said. And when we let them run our actual lives, we’re likely to get into trouble. Like Harvey Weinstein did. And it’s a kind of trouble that is at once horrifying and highly comical—that is, eminently worthy of an editorial cartoonist’s attention. And Harvey Weinstein got their attention a week or so ago. We’ve

dutifully collected a few specimens for your edification, as usual. That Harvey Weinstein’s sexual predation is no joke, that it is a serious matter, is strenuously suggested by Jen Sorensen, who, as a female editoonist, has a special insight into these matters. She offers a multiple-choice cartoon in which “ladies” can choose their own “sexual harrassment adventure.” None of the choices women have in a male-dominated society (which ours still is, despite our best efforts to equalize the sexes) are happy choices. No one wants to go there to any of them. Harvey Weinstein’s misadventure has illuminated an aspect of our society that everyone knows is there but few talk about. Journalist Gretchen Carlson, a former Miss America who exposed Roger Ailes’ treatment of women, sued over sexual harassment and won a $20 million settlement, put it as plainly as possible: “Every woman has a story,” she told syndicated columnist Kathleen Parker. Every woman? Every woman. That’s how it is in a bi-sexual society dominated by the male of the species. Every woman, at some time or another—even repeatedly—is going to be sexually harassed in some manner. Some of the males doing the harassing think they are merely hitting the girl up for a date, or hinting at it. But somehow, they’re harassing sexually. Parker’s most powerful statement in her column discussing this matter came later. I’ll let her lead up to it—: “When I interviewed Carlson recently, I confessed that I had always been a ‘guy-girl,’ raised by my father in a male-centric environment and, as a professional skeptic, had often assumed that most ‘victims’ of sexual harassment were either not tough enough, lacked a sense of humor or were stupid about guy-tude. “It turns out I was also, according to Carlson, part of the problem. (You learn something new every day.) Next I told her that I had never been sexually harassed, then proceeded to relate at least two incidents in my adult working life that were textbook sexual harassment. I simply hadn’t recognized them as such. [My emphasis—RCH] “Indeed, I did what most women do. I shrugged them off and stashed the experiences so deeply in my psyche’s Junk folder that I forgot about them — until now. #MeToo. “Cases such as Carlson’s — Ailes kept pushing her for sex so that she would ‘be good and better’ — were more clear-cut than mine. One incident was hands-on, but the other, a series of episodes in the early 1990s, was environmental. Strippers were brought in to our intimate public-relations office to perform for executives’ birthday parties. I was told I could stay home those days, which I did, but then the CEO would call a meeting and show a video of the striptease on a large screen while my boss and a half-dozen male colleagues laughed. “It wasn’t fun or funny.” I guess I wouldn’t recognize such an incident as sexual harassment either. And I suspect that many women, including my wife and my two daughters, have had experiences similar to Parker’s—experiences that they don’t recognize as sexual harassment. Because they are so ingrained in our patterns of social behavior, we simply don’t recognize them as unusual. And, indeed, they aren’t. They’re usual. They’re everyday. Parker continues, explaining—: “Sexual harassment doesn’t always mean a sexual advance, as Carlson pointed out. It’s about power through sexual intimidation. Surely, women have a right to live and work without this predatory threat. If enough fathers care about their daughters’ future success; if enough brothers care about their sisters’ safety; if enough women care enough about each other, #MeToo — or #BeFierce — won’t be just another hashtag.” Sexual harassment may not always be a sexual advance, but a sexual advance is likely always to be a form of sexual harassment. Or can be seen as such. If a man asks a woman for a date and she doesn’t want to date him, does she think she’s being sexually harassed? That’s how deep it goes. The way to deal with the Harvey Weinsteins and Roger Aileses of the world is to expose them. Even better, laugh at them. (Their penises—their sexual personalities—will shrivel.) And if we can end the conspiracy of female silence—or, to put it another way, the power of males to intimidate—we’ll be making progress. So our predicament is scarcely hopeless. But how can ordinary male admiration of the female avoid being interpreted as sexual harassment?

THE LAST EDITOON AT HAND, Matt Davies’ at the lower left of the exhibit, takes us back to where we are, not to where we aspire to be. Here again, sexual intimidation is achieved through the everyday exercise of male power. And

since we opened up the Editoonery Department for Harvey Weinstein, we may as

well take a quick look at other events of the past 10 days or so. Jeff Stahler offers a memorable image to give the Trumpet’s explanation of why he isn’t phoning more of the families of recently killed soldiers: he’s too busy. And he hasn’t phoned many of the families of the fallen. Trump brought critical scrutiny on himself, as he often does, by trying to smear Bronco Bama and/or other predecessors, claiming they didn’t phone Gold Star families either. Yeah, well—they did. Or they sent letters of condolence. And the Trumpet, it turns out, isn’t doing as well at it as he thinks he is. His big mistake, as always, is to believe that what he thinks is actual reality instead of one of his many delusions. Finally, Joe Pett takes four panels to construct a verbal parallelism that makes his point. Following the pattern that the first two panels establish, the third panel should have the Pachyderm saying: “More guns means ... more shooting.” But the National Rambo Association and the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm think in other patterns, more monetary.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS Frederick Burr Opper on the birth of Happy Hooligan—: It happened that they wanted a new series of comics, and I set about inventing one. I thought of a tramp. Tramps were not so very new; there had been all kinds of tramps, so I decided to make him a little different by putting a can on his head. What gave me the idea was that at that time all the saloons put their empty kegs in the streets for the breweries to pick up and refill. The tramps would hang empty tomato cans around their necks, go to these kegs and tip the remains of the beer from the empty barrel into their cans.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution A PROPOS AFGHANISTAN, HERE’S A QUOTABLE QUOTE—: “We could be involved in the region for the next decade if our objective is the establishment of a government there that perfectly meets some blueprint of our own devising. This is a country with an unstable political history. It is a country with an unstable political future. There are divisions in that country that are not going to be healed by anything that we do. At some point, these people are going to have to settle their own political future without our interference.” Who said it? Ed Muskie. Remember him? Onetime would-be presidential candidate. He was talking about Vietnam on the old “Dick Cavett Show,” segments of which were aired hereabouts during the Ken Burns “Vietnam War” weeks. But Muskie’s words apply to our present predicament in the Mideast’s Afghanistan. I changed a couple words to eliminate tell-tale names of countries in order to heighten the pertinence to today’s dilemmas. The pertinence is that we don’t seem capable of learning from our mistakes. The mistakes that got us into Vietnam and kept us there are the same mistakes we’re making anew in the Mideast. We’re going into a foreign country without knowing its history or culture and attempting to impose upon it our solutions for their problems. Didn’t work in Vietnam. Won’t work in Afghanistan. We stayed in Vietnam longer, far longer, than we should have because we feared that if the South fell to the North, it would initiate a domino effect that would spread communism throughout the region—and then, the world. But we left. And communism didn’t spread worldwide. It died. We’re staying in Afghanistan because we don’t want to let the country become a training camp for terrorism. What do you think will happen if we leave?

READ AND RELISH On the Internet from Jon Winokur’s Curmudgeon—: The Internet is the most important single development in the history of human commication since the invention of call waiting.—Dave Barry If television’s a babysitter, the Internet is a drunk librarian who won’t shut up.—Dorothy Gambrell We’ve all heard that a million monkeys banging on a million typewriters will eventually reproduce the entire works of Shakespeare. Now, thanks to the Internet, we know this is not true.—Robert Wilensky Doing research on the Web is like using a library assembled piecemeal by pack rats and vandalized nightly.—Roger Ebert

CARTOONING IN ESQUIRE Last month (Opus 370b) we performed an exhaustive analysis of the “new” cartoon humor being foisted off on us by Esquire’s newly appointed Cartoon and Humor Editor, Bob Mankoff, erstwhile cartoon editor at The New Yorker. Mankoff, before his chair at The New Yorker had even cooled off, was extolling the “new quality of humor” he hoped to bring to his new gig. His “new approach,” he averred, would “reinvigorate the ecosystem of magazine cartooning.” The new approach, he said, would involve his working closely with a handful of different cartoonists (even humor writers) in each issue. Esquire has been without cartoons for many years, so we looked forward to this “reinvigorated” comedy Mankoff was promising us. Well, we decided after inspection, the “new” humor was, indeed, different, especially for Esquire: as exemplified in the magazine’s September issue, it consisted mostly of observing ordinary human endeavors closely and finding tiny slivers of comedy therein—and then drawing up the slivers. This method, we allowed, produced cartoon humor that was, let us say, more “authentic”—because it was rooted in ordinary life without the usual comedic exaggeration we find in most cartoons. Authenticity, however, doesn’t make much of a splash when it’s tossed into the pond of the human comedy. Ripples are more likely. But Mankoff’s hopes still intrigue us. So when the current issue of Esquire came out, October’s, we eagerly seized upon it for another view of Bob Mankoff’s idea of a new generation of cartooning. He’s still importing cartoonists from his former haunt, The New Yorker. Altogether, there are five pages of “cartoons.” William McPhail is back with another full-page Peeping Tom cut-away view of the world, Matt Diffee offers a two-page pictorial essay, this time on surfing, and Alex Gregory makes his Esquire debut with a full-pager. Diffee’s essay is actually more verbal than visual, sprinkled with such wisdoms as this: “A good wave for surfing breaks at one spot first, allowing surfers to surf right or left, depending on political affiliation.” Ahh, the wit. The comedy of its penetrating insight. I’m prone with laughter. I’m so overcome that I can’t bring myself to show you this exemplar of modern funniness in all its hilarity. Instead, I’ve posted a mere snapshot of one page among the three quarter-page cartoons displayed in our first visual aid—enough of a glimpse to assure you that Diffee’s effort is not cartooning: the pictures add very little to the humor, which is all verbal, of the kind I just quoted.

An ostensible fifth page is actually made up of three quarter-page cartoons by another debut tooner, Seth Fleishman, all under the heading “Spot On.” His work is distinguished by its utter simplicity in rendering. The comedy in the first two in the visual aid at hand (going clockwise from the upper right) seems to be about modern technology. But the first one involves the old Polaroid camera, which is no longer around. I doubt that any of Esquire’s new crop of with-it readers knows much about Polaroid cameras. And the joke in the third one leaps unerringly even further into the distant past with a horse-and-buggy image of some sort of bondage. Funny? I thought I’d never laugh. Gregory’s page is a blasphemous look at the life of God before Genesis and “the Creation.” God, it seems, was hanging out with Leslie, a female of whatever their species. Their relationship is complicated by God’s omniscience: he knows whatever Leslie is going to say or do before she says or does it. Tiresome. So she leaves and takes up with another superbeing. And then God wanders into his basement workshop where he contemplates creating Man from some dust on his workbench. It’s an amusing whimsical concept, but the comedy is all in the prose. The pictures contribute very little apart from visualizing the characters. In a cartoon, pictures carry half the comedic load. So Gregory’s contribution, like Diffee’s, is not a cartoon. Mankoff’s title is “Cartoon and Humor Editor,” so Gregory’s work is well within his purview. Mankoff’s idea of cartoon humor embraces whimsical fantasy as well as authenticity. As for McPail’s offering, I’m still not sure what he thinks is humorous about the scenario he’s presented. The woman at the laptop at the bottom of the page is apparently the same woman we see at the top of the stairs at the upper right. So she’s walked downstairs, witnessing the light-bulb idea on every floor until—until she has the same idea herself? Or is she swiping the idea from everyone else? And the guy looking over her shoulder—he’s the guy pictured on the floor above, taking the light bulb idea from the woman in the bubble? The title of the page, “Genius,” suggests that McPhail thinks genius is more borrowed than originated. Geniuses, in other words, aren’t kingdoms unto themselves alone: they’re inspired by what’s around them. So how’s that funny? With McPhail’s cartoon in the previous issue as a guide, we assume that this month’s offering, like last month’s, is not intended to be funny, exactly. It’s insightful, a glimpse into aspects of human existence that are not always readily apparent. It tells us something about ourselves in a way that makes us smile, ever so slightly.

THESE RIPPLES OF COMEDY are pretty far from the sort of cartoon comedy that prevailed in Esquire for the first quarter century of its life. When the magazine started in 1933, it ran huge, full page color cartoons. And the comedy was distinct from that to be found in The New Yorker, which, the Esquire editors conceded, had a near-monopoly on “whimsy”; Esquire’s forte would be, the editors proclaimed, “whamsy.” Just to remind you of what whamsy is—or, was— here’s a short harvest of cartoons from the magazine’s 25th anniversary collection.

Just before post time, the November issue of Esquire appeared in my mailbox. It, alas, has only two cartoons: a full-page comic strip by Drew Dernavich (in a wholly unaccustomed drawing style) and another incomprehensible quarter-page panel by Fleishman. Judging from this paucity, could be Mankoff’s grand experiment is coming to a close.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

JEFF MACNELLY’S

comic strip Shoe has reached its 40th birthday, as we can see

in the first strip of our line-up. One of Robb Armstrong’s characters in Jump Start, Clarence, is doing in the first panel what comic strip characters are forced to do in these sensitive times: instead of swearing with actual swear words, he’s swearing with little stars and sqwirls and skulls and crossbones—symbols that won’t offend anyone. But I can’t make out the symbol just to the right of the giant exclamation point. Is that a trash can? With something coming out of it? What is it? For insight and wisdom, we can’t beat Jef Mallett’s eponymous Frazz, who explains how sameness can appear to be newness. Frazz is always pretty smart while Earl in Brian Crane’s Pickles is only occasionally wise—as he is in the example posted here. And finally, still in a celebratory mood, here’s a wonderfully predictably pun in Hilary Price’s Rhymes with Orange. I mean, how many of us have tried, unsuccessfully, to find the comedy in sound-alikes slay and sleigh? Price shows how to do it.

*****Book Review Book Review Book***** By the way (although not at all incidentally), to commemorate Shoe’s 40 years in the funnies, a retrospective collection of the cartoons has just been issued by Titan Comics (240 9x9-inch pages, b/w with a section of color Sundays, $29.99), The Best of Jeff MacNelly’s Shoe. The reprints are arranged in chronological-order sections, beginning with the first strip, September 13, 1977, which we’ve already seen. The book begins with a clutch of essays—a Foreword by Dave Barry (Backword by Mike Peters), a history of Shoe (by MacNelly’s widow and another by his brother), and a MacNelly biography. MacNelly, who was the Chicago Tribune’s editoonist as well as Shoe’s perpetrator, died of lymphoma on June 8, 2000, having produced the strip single-handedly for 23 of its 40 years. Appropriately, slightly over half the book reprints his Shoe; the rest belongs, first, to Chris Cassett and Gary Brookins, who took over the strip upon MacNelly’s death; and then just to Brookins. Sue MacNelly, the widow, is listed as one of the strip’s writers; Bill Linden and Doug Gamble, the others. My guess is that she approves what they write; then Brookins draws it. This may be the place to tell a couple stories about MacNelly, who was storied himself (and several stories tall, up to six foot five). He once worked in an office (first in Washington, D.C.; then at the Chicago Trib), but in later years, he worked at home in West Virginia. He was always pressed by a looming deadline because there were many other things he enjoyed doing that took him away from aiming at the deadline. He said the advent of Federal Express let him beat his deadline by a day. Once. And when it became possible to transmit his cartoons digitally, he beat his deadline again by a day. Once. Like many cartoonists, he experimented with drawing instruments. Finally, he said, he settled on a ballpoint pen, the least likely of choices. At a cartoonists convention once, he was standing with two other cartoonists, all over six feet tall. I wandered over and asked if being over six feet tall was a requirement for being an editorial cartoonist. MacNelly said that it helped. Most of us, impressed by his talent and the range of his artistic aspirations and accomplishments, thought he was one of a kind, irreplaceable. But his wife Susie once said, “They say there are others like him on his home planet.” In The Best of Shoe, we can catch glimpses of his home planet. And that includes some of the earliest characters, many of whom don’t appear very often any more—Irv Seagull, Madame Zoo Doo, Mort (the aptly named operator of a mortuary), and the beloved looney Loon, mail and newspaper carrier whose aeronautic skills are scattered, to say the least; and Cosmo’s nephew Skylar, who spends afternoons practicing football with giant-sized teammates and opponents and his summers in the Marines, thinking it’s summer camp for boys.

ON SEPTEMBER 11, I posted the first page of this next display on my Facebook page. And several alert observers told me of other 9eleven commemorations on that date, a few of which (Wizard of Id, Heart of the City, Dick Tracy, Dogs of C Kennel, Mallard Fillmore) I’ve posted on our second page. Hank McNamara also did a remembrance strip about how easy it is to forget.

THE ALIMENTARY

SNAFUS of normal life continue to preoccupy strip cartoonists. The dolphin in Patrick O’Donnell’s Mutts is talking out of his blowhole, sez Earl. With my predilection for detecting gaseous comedy, I am suspicious of “blowhole.” Yes, dolphins have blowholes, and I know what they are, normally. But I can’t be sure O’Donnell isn’t engaging in a little risque word play here. Not one to let a good detour escape unheralded, here’s re-tweet from The Week (September 22), in italics—: A judge in Berlin has upheld a man’s legal right to fart in front of police officers. The defendant, identified only as Christoph S., broke wind twice during an identity check by a policewoman in February 2016. Police charged that Christoph “insulted” her “honor,” and a judge ordered him to pay a $1,110 fine. But he appealed the decision, and last week a magistrate’s court judge ruled in his favor. Christoph’s lawyer said it was not surprising that police wanted him punished, but the fact that the prosecutor’s office pursued a farting case was a “failure of the state.” To each his own weapon. Back to alimentary matters with Crankshaft by Tom Batiuk and Don Davis. “Pee” is a word we aren’t accustomed to seeing in the funnies. I’ve always thought “pee” is the word choice of women, who, being more refined than me, choose the gentler version of “piss,” the masculine choice. But then I’m just making this up as I go along.... Turning away, for the nonce, from scabrous subjects, we have Stephen Pastis in Pearls Before Swine treading close to Biblical matters—and, hence, to loads of letters of objection by the religiously fervent. Finally, off the subject of risky comedy altogether, here’s Wiley Miller with a Non Sequitur of surpassing insight. Glad I caught this one.

POLITICS,

particularly those of the Trumpet, are so laughable lately that comic strips

are venturing where they dared not go a generation ago—namely, into politics.

Today’s tour, however, involves three habitual offenders. Carmen, his li’l desert girl conservative in the strip, is put-off no little by the skunk that looks amazingly like the Trumpet (thanks to Eric Allie who is drawing the strip these days). Lalo Alcaraz in his La Cucaracha strip hasn’t hesitated lately in aiming a shaft or two Trumpet-wise. And the strip third down the line-up is no exception. Finally, we have a brace of Non Sequiturs by Wiley Miller, who was once an editoonist—so his political darts are scarcely unexpected. A recent sequence, two of which we see hereabouts, took veiled shots at the GOP and its failed attempts to repeal Obamacare and replace it. In Miller’s formulation (surely he noticed this?), Obamacare has assumed the omniscience of gravity itself. Bravo, I say.

SOME ODDS &

ENDS this time, including a few that warmed the cockles of this ol’ heart. Charlie Brown from Charles Schulz’s celebrated comic strip masterpiece Peanuts shows up three times here, the first two in strips that have heart-warming (and risibility gratifying) punchlines. I love Sally’s panic attack at the prospect of going to school in a few days: her exaggerated reaction is both pure comedy and wonderful satire. With Sally and her consuming fear and Peppermint Patty with her complete ineptitude, Schulz managed to nail some of public education’s secret faults. But Sally’s panic is without equal in comics. Charlie’s third appearance here is in Brian Bassett’s Red and Rover, where he shows up in a perfect imitation in the last panel. Bassett dutifully credits Schulz, noting at the top of the second panel, “With apologies to the late, great Charles Schulz.” Alas, Charlie Brown has become so integrated into American culture that Schulz often isn’t credited in this customary lingo that cartoonists used to employ in such instances. Jimmy Johnson’s Arlo and Janis ends on a nicely romantic note. Another warmer. And here’s Carmen and Winslow in Scott Stantis’ Pricky City again, another shot at our detranged Prez. At the upper right, we have another instance of Tom Batiuk and his drawing partner Don Davis tilting their Crankshaft strip on edge, displacing the usual horizontal format of comic strips with a vertical. And we’ve displayed it here as a vertical (in order to get it on this page) rather than as a horizontal, which is how it was published in my local paper. Batiuk has done this twice in the last month or so, both times in Funky Winkerbean, his other strip.While there is some justification for resorting to this device in both of those instances (see Opus 370 for explanation), there’s little justification here. Here, it looks as if Batiuk and Davis have turned the strip on its edge just to save the effort of drawing the two characters simply conversing in three or four panels. Well, yes—the girl is holding a pole upright, ostensibly helping Ms. McKenzie dust, and the verticality of the pole is emphasized by the verticality of the strip. But the pole is scarcely serving as a punchline or any other essential aspect of the strip and so it doesn’t need the emphasis. I think Batiuk and Davis are just taking a shortcut. And in so doing, they forfeit an opportunity to give the little girl’s last comment some poignance by isolating her in a single panel by herself.

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing

Hank Ketcham’s self-portrait, like others I’m posting hereabouts over the next few months, was done for a series that the Collier’s magazine ran about its cartoonists. (Maybe it was Saturday Evening Post; but I think probably Collier’s.)

Ketcham’s left cheek is disfigured by a jagged six-inch scar that runs across his visage. I doubt that this aspect of his appearance shows up anywhere else—certainly not in any other self-portrait. Curiously, Ketcham doesn’t mention either the scar or its cause in his autobiography, The Merchant of Dennis. Before the book was published, Ketcham removed the part that explained the scar. He got it in a car accident when he was 16 years old. The car, driven by a friend of Ketcham’s, blew a tire and, out of control, ran into a telephone pole. Nobody in the car was hurt—except Ketcham, whose face was slashed. “Some kind man sped me to the County Hospital where I was quickly stitched and bandaged by a nearsighted intern. Thus the six-inch scar that I have sported ever since.” How do I know all this? Because Ketcham sent me a sheaf of papers after I’d reviewed the autobiography. He liked the review and thought (rightly) that I’d be interested in the “out-takes,” the portions of his life story that he omitted for one reason or another. (Mostly, I suspect, because the tales weren’t funny enough to take up pages from the ration the publisher allowed him.) Ketcham tells about the accident with the sure instinct of an accomplished comedic writer. He begins: “Every time we [Hank and his teenage friends] went out for a drive, Grandmother Ketcham would stubbornly harp on the principle of wearing freshly laundered clothes. ‘In case you’re in an accident, you know,’ she would add. Apparently her concern was less for possible injury than the horror of being found wearing dirty undies.” Then Ketcham relates the events of that evening in 1936 Seattle—the car crash, the wreckage, discovery of the blood streaming down his face, his visit to the hospital and the nearsighted intern. Then he ends his story: “Grandma Ketch would be pleased to know that, right up until the moment of collision, my BVDs were spotless.”

TICS & TROPES Derf Backderf (The City, Trashed and My Friend Dahmer) says his work as a storyteller is built on the journalism instruction he received at Ohio State University years ago. “That’s the way I learned how to tell stories,” he told Joel Oliphint at columbusalive.com. “You go out and research it, gather the facts, and then you tell the story. It’s the one thing that stuck with me from college.”

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews THE RANCID RAVES Book Grotto is littered, literally, with books we acquired with the intention of reviewing them. Alas, they’ve piled up over the years, and it has become increasingly apparent that we’ll never give most of them the kind of intensive examination they deserve. So rather than let the accretion be entirely in vain, we’ve started this new department wherein we’ll briefly describe books by way of urging them upon you, beginning, this time, with—:

From Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin By Steven Brower with Peter and Philip Meskin 220 9x12-inch pages, some color but mostly b/w; 2010 Fantagraphics hardcover, $39.99 FITTINGLY, in a book about an artist, pictures predominate. Beginning with Meskin’s teenage art, the book includes youthful pulp illustrations and then on to covers and pages of the Golden Age comic book characters he’s most associated with—Vigilante, Fighting Yank, Black Terror, Golden Lad and Johnny Quick (for whom Meskin innovated the use of multiple figures to show the character’s speed, the so-called “strobe figure motion”)— unpublished art, sometimes whole stories; paintings in color, color roughs, advertising art from his later years, including storyboards for tv commercials, and lots of original art, some comic book pages in pencil. The narrative relies heavily upon the quoted memories of Meskin’s two sons and of Jerry Robinson, with whom Meskin roomed early in his career and later collaborated. They were lifelong friends and mutual admirers. I was a fan of Black Terror in my youth, and I once asked Robinson who did what in collaborating on the feature. What he told me astonished me: they alternated penciling and inking—sometimes from panel to panel. Robinson repeats and elaborates upon this fascinating fact in the book. Even more fascinating is Alex Toth’s tribute to Meskin in a two-page sidebar essay. “Mort Meskin broke rules, created his own (and years of splendid artistry along the way)—most notably in his Vigilante and Johnny Quick series. ... His invention, daring, and subtlety were unique and exciting to us young Turks and old pros. Mort created surprises, beauty, action, and mystery art through his keen talent for the unusual viewpoint, layout, composition, lighting, massing of forms and solid shapes, rich blacks and line work, in ways deceptively simple, bold, strong (yet subtle, remember), and clearly-stated. ...” “Mort shifted gears/viewpoints/emphasis and methods throughout his career ... he invented, questioned, assessed, discarded, tested, reached out ... more than ten other cartoonists of his time .... His restlessness kept him facile ... as he learned, tested, and applied ... and so did we, his observers and students.” Toth described Meskin’s method of laying out a page. First, he rubbed a soft-lead pencil across the entire surface of a blank piece of paper, and then he took a kneaded eraser and, referring to the script, “proceeded to ‘pick out’/erase panel borders ... and then solid shapes of each panel’s interiors—a caption block, a balloon, a figure, another. Working in reverse, he erased shapes, forms, interlocking compositional elements, to create complete (but negative/white on gray) pictures.” Then he filled the blank white spaces with drawings. Steve Ditko offers another sidebar essay, extolling what he admired most about Meskin’s work—his storytelling ability. Throughout his life, Meskin was a prolific worker but shy. In his second wife, however, he found someone who nurtured his confidence, turning him into a raconteur (even when, after throat cancer had robbed him of a larynx, he used an electronic transmitter to speak). Insightful as the essays and testimonies are, the book’s pictures are its greatest trove of Meskin.

CLIPS & QUIPS From Neil Gaiman, quoted by Hayley Campbell in theguardian.com: I’m convinced if I keep going, one day I will write something decent. On very bad days, I will observe that I must have written good things in the past, which means that I’ve lost it. But normally, I just assume that I don’t have it. The gulf between the thing I set out to make in my head and the sad, lumpy thing that emerges into reality is huge and distant, and I just wish that I could get them closer.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words

SHANNON WHEELER’s book of Trumpt tweets, Sh*t My President Says, is now out. (It hadn’t arrived before I did my mini-review last time.) Here with, a few telling tweets from our twitterpated Prez.

THE INSIDE

COVER of Image+ magazine is usually a comic strip commentary on the medium

by Brandon Graham. In No.10, however, Adam Warren sits in, and

his page

AND FINALLY,

just for the malicious fun of it, here are some spot drawings made by Nishant

Choksi for a recent issue of The New Yorker. The magazine can’t

refrain from poking fun and the fingerbone of scorn at our Beloved Leader.

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”—James Baldwin “Resentment is like drinking poison and hoping it will kill your enemies.”—Nelson Mandela “You can never go wrong by voting for a bill that fails, or against a bill that passes.”—Bob Dole “The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.”—John Kenneth Galbraith

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—:

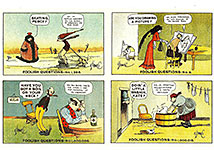

Foolish Questions & Other Odd Observations: Early Comics, 1909-1919 By Rube Goldberg; edited by Peter Maresca and Paul C. Tumey 96 9.5x10-inch pages, mostly b/w but some color; 2017 Sunday Press, $35 GOLDBERG GOT HIS NAME IN THE DICTIONARY by doing a long series of single-panel cartoons depicting hilarious inventions that deployed complicated mechanisms to accomplish very simple operations, his satire on the dawning modern times. But before he did inventions, he did Foolish Questions. And those made him famous. Foolish Questions was the title of a single panel cartoon that Goldberg tacked onto an otherwise unrelated comic strip. In common with many newspaper cartoonists in the early years of the 20th Century, Goldberg drew innumerable comic strips and cartoons, most of which were short-lived features that lasted a week or less. But Foolish Questions was a maneuver that could be perpetuated indefinitely by adding it to whatever his comic strip that week was. The best way to tell you about Foolish Questions is to show you Foolish Questions, which we’ve done at the end of the paragraph after the next one. The volume at hand includes essays by Jennifer George (on “When did you find out you were Rube Goldberg’s granddaughter?”), Tumey (on Goldberg’s career) and Carl Linich (on other Goldberg strips-within-strips features). Some of the other short-lived cartoons include Mike and Ike: The Look-Alike Boys, Telephonies, I’m the Guy (“who put the cast in overcast”), I’m Cured, Old Man Alf of the Alphabet, Boob News, I Never Thought of That, The Boob Family, and Silly Sonnets. To name a few. As always with a Sunday Press book, there’s an extra publication included with the book itself: in this case, four postcards with FQs on them. But who would ever part with them to mail them off to anyone? (A foolish question.) The first Foolish Question panel appeared October 23, 1908. It was popular enough that the panels were collected in a book published in 1909. Goldberg started numbering the FQs, but the numbers soon became wholly frivolous and altogether nonsequential. Dunno whether the book at hand reprints all of the FQs or only a judicious selection, but there are about 300 of them here, enough to convince you that Goldberg deserved the fame they brought him. Here are some of them and a sample of the other Goldberg comics that are presented in the balance of the book.

Jerry and the Joker: Adventures and Comic Art by Jerry Robinson By Jerry Robinson; edited by Daniel Chabon and Hannah Means-Shannon and Robinson’s son Jens Robinson, who also supplies “notes” (it sez here), a summary of his father’s achievements 151 9x12-inch pages, b/w and color; 2017 Dark Horse hardcover, $34.99 CHIEFLY A SCRAPBOOK OF ROBINSON’s art over a long career that included cartooning in many of the medium’s genres, this volume offers samples of his early work on Batman (several pages from original art, displaying a much more flexible line than is usually associated with Batman drawn by other artists), Atoman, and miscellaneous comic book work for westerns, crime, etc., sketches of scenes from his travels, theatrical drawings for Broadway’s Playbill magazine, magazine illustrations, and a couple samples of his political/social commentary feature, Still Life, which ran for over 30 years. But, alas, almost nothing from the period when he collaborated with Mort Meskin on Black Terror, Fighting Yank, Johnny Quick and Vigilante. (For more about that, see the above review of the Meskin book, From Shadow to Light; oh, you’ve already read the review? Well, then you know....). And no samples of the Jet Scott comic strip that he drew September 28, 1953 - September 25, 1955, starring a James Bondish swashbuckling womanizing agent whose debut coincided with that of Ian Fleming’s 007 who first appeared in April 1953 in Casino Royale (too unheralded at the time to inspire either Robinson or Sheldon Stark, who wrote the strip). But the Batman material and Robinson’s theater sketches are worth the price of admission alone. Pages of pictures are punctuated with essays by Robinson, who regales us with his adventures in Cuba and Rome (where he met Clifford Irving, the infamous author of the fraudulent biography of Howard Hughes and also the son of Jay Irving, who drew the comic strip Pottsy about a comical cop). Two of his other essays cover his introduction to comic book illustration working for Bob Kane, and the invention of the Joker. The latter has been disputed by various people, but writer Bill Finger, who is sometimes credited as the co-creator of the Joker, is quoted herein saying Robinson created the funnybook medium’s most despicable villain. I explored this topic several years ago and satisfied myself that Robinson’s claim was legitimate. Robinson’s 6-page essay in this volume explores not just his invention of the character but villainy generally in comic books (and elsewhere). The book concludes with a brief 2-page biography of Robinson. In it, we learn that he was once president of the National Cartoonists Society and, on another occasion, prez of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists—the only cartoonist to have served in that role in the two principal national organizations for cartooners. He also founded and ran for many years Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate (CWS), affiliated with the New York Times, which syndicated the work of 350 leading cartoonists and graphic artists from 50 countries. And he was one of the prime movers in getting Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster recognition and recompense for their creation of Superman. Robinson was, in short, a giant in his chosen field. But when all is said and done, I don’t know why this book was published. It leaves out too much of Robinson’s career to be a biography or even, what it purports to be, a complete scrapbook of his art. The Joker essay and various comic book covers depicting the Joker plus a Joker Batman tale reproduced from original art take up less than a couple dozen pages, scarcely enough of the book’s 151 pages to justify including the character’s name in the title. And including Robinson’s theater and other sketches effectively dilutes the book’s content so we can’t characterize it as focusing on Robinson’s comic book career. Probably Robinson’s exhaustive Joker essay is the germ around which the volume developed. Some of the book’s artwork appeared in Chris Crouch’s excellent 2010 biography, Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of Comics (224 8x11-inch pages, b/w and color; Abrams Comicarts, $35), which, produced while Robinson was still alive (and using original art from Robinson’s inventory—and he hoarded great quantities of his art), is about as authoritative as is possible to be. From Crouch’s tome, here are some of Robinson’s Still Life and, later, Life with Robinson political/social commentary cartoons and a few of his True Classroom Flubs & Fluffs, a feature that illustrated mistakes in the utterances of school kids. And I’ve also included the sexily charged bodacious splash page he and Meskin did for a Black Terror story and a page from another Black Terror story plus a sample of his Jet Scott comic strip.

Forthcoming (briefly noted) some of my likely favorites—: Going into Town: A Love Letter to New York, Roz Chast; out October 3—an irresistible love letter to the city Monograph, Chris Ware; October 10—doodles Poppies of Iraq, Brigitte Findakly plus Lewis Trondheim; September 5—chronicle of her relationship with her homeland co-written and drawn by her husband Sex Fantasy, Sophia Foster-Dimino; September 12—a moving look at intimacy in all its delicacies and absurdities Run for It: Stories of Slaves Who Fought for Their Freedom, Marcelo D’Salete; October 10 Tenements, Towers & Trash: An Unconventional Illustrated History of New York City, Julia Wertz; October 3—sidesplitting history based upon Wertz’s columns in The New Yorker and Harper’s Sugar Town, Hazel Newlevant; October 10—a bisexual, polyamorous love story Jane, Aline McKenna and Ramon K. Perez; September 19—reimagines Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre set in present-day New York Ditko’s Mr. A.: The 50th Anniversary Series, Book One, The Avenging World; October 24 As the Crow Flies, Melanie Gillman; October 10—a collection of the webcomic about a queer, black teenager in an all-white Christian youth backpacking camp Mr. Higgins Comes Home, Mike Mignola teaming with Warwick Johnson Cadwell; October 18—sendup of classic vampire stories Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures, Yvan Alagbe; October 24—race and immigration in Paris by one of France’s celebrated cartoonists The Story of Jezebel, Elijah Brubaker; already out—hilarious take on the Old Testament tale of paganism, murder and sex, with satirist wit and visual verve All of these, including comments, taken from Heidi MacDonald’s “Fall 2017 Announcements: Comics & Graphic Novels” in publishersweekly.com; June 23