|

||||||||

Opus 343 (September 5, 2015). In a loose-limbed ramble of Recreational Reading, we visit great caricaturists (Max Beerbohm, Ralph Barton and Aubrey Beardsley with stops at Oscar Wilde, Frank Harris, Bernard Shaw and Shakespeare—for the First Folio), and we rant about the Froth Estate and Trump (an editoonist’s dream), take a look at the month’s editorial cartoons and commit several reviews—first issues of comic books Prez, Dark Corridor, Barb Wire, Eight; Summer Blonde, Desmond Puckett, early Jonah Hex, The League of Regrettable Superheroes, Bravo for Adventure—and report some of the latest comics news (Iranian artist gets courage award, presidential candidates in funnybooks, Alcaraz joins Disney, alarm about Playboy’s cartoons and more). Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Iranian Artist Gets Courage Award Presidential Candidates in Funnybooks Lalo Alcaraz Joins Disney for “Coco” Zunar Gets Cash Award Another Moral Purity Prank on Campus Mad’s Gaines Wouldn’t Desist Alarm about Playboy’s Cartoons Time Publishes Cartoons Marvel Comics in Time Joe Hill in a Graphic Narrative

ODDS & ADDENDA Word Balloons on TV Cartoon Art Museum Closes Temporarily Since 1990, 138 Comics-Based Movies Robert Ariail Back Full-Time Editoonist Ohman Wins Best of the West

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of—: Prez No.1 Dark Corridor No.1 Sparks Nevada, Marshal on Mars Barb Wire No.1 Lobster Johnson in “Chain Forged in Life” (one shot) Eight Nos. 1-5

THE FROTH ESTATE The Trumpet

EDITOONERY Reviewing Some of the Best of Last Month’s Editorial Cartoons

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Review of Summer Blonde

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Playing with the Form in 9 Chickweed Lane

BOOK MARQUEE Reviews of—: Desmond Pucket Makes Monster Magic Jonah Hex: Welcome to Paradise

BOOK REVIEW The League of Regrettable Superheroes

GRAPHIC NOVELS Review of Bravo for Adventure

RECREATIONAL READING Rambling through—: Max Beerbohm Oscar Wilde Ralph Barton Frank Harris Bernard Shaw Aubrey Beardsley Shakespeare First Folio

PASSIN’ THROUGH Randy Glasbergen

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

IRANIAN ARTIST WINS COURAGE AWARD “She refused to be brought down.” With these words in a press release, the Cartoonist Rights Network International (CRNI) awarded its 2015 Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award to Atena Farghadani, the jailed Iranian artist who last spring was sentenced to more than 12 years in prison for her editorial art and community activity critical of the government. Farghadani, 29, was jailed in Tehran in August of 2014 after publishing a cartoon in protest of proposed legislation that would restrict birth control and women’s rights in Iran. Following her release four months later, Farghadani posted a YouTube video recounting her beatings and mistreatment while in prison. In anticipation of her trial on charges that included “spreading propaganda against the system,” Farghadani wrote a defiant open letter to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in which she said: “I know … I will be in a court that screams injustice. I will be present before a judge who for years has skewed the balance of justice … What you call an ‘insult to representatives of the parliament by means of cartoons’ I consider to be an artistic expression of the … parliament which our nation does not deserve!” As a result of that letter and her YouTube posting, Farghadani was returned to prison in January, 2015. In May, she was tried and found guilty of “insulting the Iranian supreme leader and members of parliament” chiefly by depicting them as mindless animals, following a vote curbing reproductive rights. Atena Farghadani was sentenced to 12 years, nine months in prison. (See Opus 341 for details and illustrations.) “Atena is among the most courageous humanitarians we know of,” Robert Russell, founder of the Northern Virginia-based CRNI, told ComicRiffs. “When they tried to intimidate her with physical torture, she just punched right back — she refused to be brought down. Her imprisonment under this regime is one of the most unjust acts in Iran’s modern history. “This year,” Russell continued, likening Farghadani to other noted heroines, “the decision about the award recipient was easy. It was a unanimous decision by the CRNI board of directors.” The staff of Charlie Hebdo was also considered for CRNI’s honor, Russell noted, but the board weighed that Farghadani has received less world attention and fewer accolades compared with the French satirical weekly since the attack at its offices in January left a dozen people dead. Soon after the announcement about the award came news that Farghadani has developed signs of lymphatic disease in prison as she awaits her chance to challenge a 12-year prison sentence in the appeals court. “The illness showed up recently and we are waiting to see if they send her to a specialist or to the prison infirmary,” her lawyer, Mohammad Moghimi told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “We hope that considering her health issues, the sentence against her will be changed in appeals court.”

PREZ CANDIDATES IN THE FUNNYBOOKS StormFront, formerly Bluewater, has an ambitious publishing agenda over the next year. Specializing in comic book biographies of celebrities and politicians, the roster of the latter is full for the foreseeable future. Publisher Darren G. Davis told Michael Cavna at the Washington Post’s ComicRiffs that “there are so many players in this election to date, we have a lot of material and subjects to choose from that will last us through November 2016.” In 2008, the publishing house launched its Political Power line of books with comic biographies of Obama, Biden and Hillary Clinton, as well as McCain and Palin. Now, StormFront is focusing on political dynasties, releasing its newest book, Political Power: Jeb Bush — Legacy, in August. The cover portrays the candidate straining to literally uphold the Bush name like a political Atlas. Forthcoming from StormFront are comic biographies of such candidates as Bernie Sanders, Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz, and a recently updated Donald Trump bio-book.

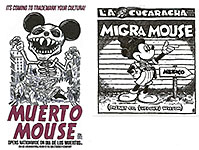

LALO TO JOIN DISNEY EFFORT ON DAY OF THE DEAD Lalo Alcaraz, Mexican-American political cartoonist and creator of the syndicated comic strip La Cucaracha, announced on Twitter on August 17 that he’s been hired to work on Pixar’s just-announced Day of the Dead feature “Coco.” Some of his Twitter followers initially assumed that Alcaraz, a respected voice on political and cultural issues related to Mexican-Americans, was joking — and for good reason, opined Amid Amidi at cartoonbrew.com. A couple years ago, Alcaraz was highly visible in attacking the Walt Disney Company. In 2013, recalled Griselda Nevarez at nbcnews.com, Disney attempted to trademark the Day of the Dead, and Alcaraz, as outraged as many in the Latino community, created a faux movie poster of a skeletal Godzilla-sized Mickey Mouse and named it Muerto Mouse. At the top of the poster he wrote: "It's coming to trademark your cultura!" Over 10,000 posters were printed and used in protests throughout North and South America, Amidi claimed, as well as during a picket at Disneyland Park. And

that’s not all. Nevarez continues: “And before Muerto Mouse, in 1994, Alcaraz

published a book of political cartoons titled Migra Mouse: Political

Cartoons on Immigration. On the front cover was Mickey Mouse dressed in a

Border Patrol uniform. Alcaraz created Migra Mouse to call out Disney for

supporting then-Governor Pete Wilson, who championed Proposition 187 that

sought to ban most public services to undocumented immigrants.” But these days, Amidi reported, Alcaraz has softened his tone toward the Disney corporation. “When one Twitter user said Disney ‘just want [sic] money not to teach culture,’ Alcaraz defended the Disney company. He explained that Disney, which generated nearly $50 billion in revenue last year, had learned their lesson about cultural appropriation from his Muerto Mouse comic.” Reaction from his followers regarding his new role with "Coco" has mostly been positive and encouraging, Nevarez said. One person said on Twitter that Disney "heard our anger" regarding its attempt to trademark Day of the Dead and "responded correctly in hiring a great talent." Another tweeted that Alcaraz has "put in time, dedication and hard work into this" and that people "should celebrate not hate." But some, Nevarez went on, questioned why Alcaraz decided to work with Disney after criticizing the company in the past, referring to him as a sell-out and a "Tío Taco," which is equivalent of the derogatory slur "Uncle Tom." Alcaraz has responded by saying he is "a Chicano artist" who wants to ensure "Coco" reflects the true meaning behind the Mexican Day of the Dead holiday. He also said he hopes to "consult on the story and the look" of the film. "These movies are being made with or without our input," he said on Twitter, referring to films that reflect the Mexican-American culture. "I believe it's better to have input, don't you?” Alcaraz has been offering input as a consulting producer on Seth MacFarlane’s upcoming tv series “Bordertown.”

CASH AWARD TO ASSIST ZUNAR IN HIS FIGHT Controversial Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, popularly known as Zunar, has been recognised by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) for his fight to uphold freedom of expression. Themalaymailonline.com reported that Zunar has received the Hellman Hammett award, a cash prize that will help him battle the nine sedition charges brought against him by the government over his cartoons which often ridicule Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Abdul Razak’s administration for sentencing Opposition Leader Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim to five years’ jail for sodomy, probably a trumped up charge. In presenting the award, reported zunar.my/news, Phil Robertson, Deputy director of the Asia division of Human Rights Watch, noted that it is the financial and ideological commitment of the famous American play-write Lillian Hellman that makes it all possible and he consequently said “a few words about her and the award that bears her name and that of her long-time partner, novelist Dashiell Hammett: “Hellman and Hammett established this award to provide moral support and financial assistance to writers in financial need who have been victims of political persecution for their writings. The commitment came from their own experience in the US during the anti-communist witch-hunts during the 1950s, when they were hauled in front of various Congressional committees. “During her interrogation by the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Hellman famously said on May 19, 1952, that ‘I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.’ “She refused to testify, leading to her black-listing and years of difficulties finding work. Hammett came before the U.S. Senate Internal Security Subcommittee headed by none other than Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, who for nearly a decade set new standards for creating evidence-free political hysteria. Hammett served time in prison because he refused to answer questions. “Unfortunately, there are still far too many writers in SE Asia, and other parts of the world, who face prison and worse for their writings, and for the acts they write about. Zunar is one of these brave writers and artists who is facing over 40 years in prison simply for expressing his opinion via Twitter. He ran afoul of the government and the IGP – who was called a shark in the Malaysian twittersphere in an article in the New York Times – because he dares speak his mind as a political cartoonist. “[The] Malaysian [government] has been pursuing him in court, while at the same time trying to starve him financially by making it impossible for him to publish his books in Malaysia. As a cartoonist, selling his books is a part of his livelihood ... “Human Rights is enormously proud to give this important award to Zunar and to reiterate the commitment of international campaigners around the world to support him as he exercises his right to freedom of expression.”

ANOTHER MORAL PURITY PRANK ON CAMPUS At Duke University, one of the books on an optional reading list for incoming freshmen offended the moral sensibilities of some of the intended readers, but nothing came of it except some publicity that, once again, has branded American colleges as hotbeds of political correctness or religious convictions gone berserk. The book, of course, was Alison Bechdel’s 2006 graphic memoir Fun Home, which chronicles her relationship with her closeted father and her coming out as a lesbian, an exploration of questions of sexual identity conducted with candor and the kind of clarity only pictures can achieve. In writing about the event, Jacob Brogan at slate.com quotes Simon Partner, a professor of history who had contributed to the choice, who told Duke Today that the book’s very complexities helped make it worth reading. “I think this [controversial material], in turn, will stimulate interesting and useful discussion about what it means, as a young adult, to take a position on a controversial topic,” Partner told the paper in April. But thinking and discussing uncomfortable topics is not something every college student wants to do. Many, in fact, would rather suppress the opportunity than take advantage of it. At Duke, some students have taken a public stand on Bechdel’s book by simply refusing to engage with it. Ignore it, and it’ll go away. Brogan refers to the Duke Chronicle that reports that a freshman named Brian Grasso “posted in the Class of 2019 Facebook page [on] July 26 that he would not read the book ‘because of the graphic visual depictions of sexuality ... I feel as if I would have to compromise my personal Christian moral beliefs to read it.’ ... igniting conversation among students,” many of whom objected to the book and its content on moral grounds. The University issued a statement, saying that the book is not assigned reading; it is entirely voluntary. The statement continues (in italics): Like many universities and community, Duke has had a summer reading for many years to give incoming students a shared intellectual experience with other members of the class (you can see the most recent selections at https://studentaffairs.duke.edu/new-students/common-experience). The reading is selected by a committee of students, and staff, who then solicit feedback from other members of the Duke community. Fun Home was ultimately chosen because it is a unique and moving book that transcends genres and explores issues that students are likely to confront. It is also one of the most celebrated graphic novels of its generation, and the theatrical adaption won the Tony Award for Best Musical, and four others, in 2015. As we have every year, we were fortunate to have the author join us on campus for a lively discussion of the book during orientation week. The summer reading is entirely voluntary – it is not a requirement, nor is there a grade or record of any student’s participation. With a class of 1,750 new students from around the world, it would be impossible to find a single book that that did not challenge someone’s way of thinking. We understand and respect that, but also hope that students will begin their time at Duke with open minds and a willingness to explore new ideas, whether they agree with them or not. But Grasso and his kindred spirits had no intention of keeping open minds or permitting themselves an encounter with something new and different. Brogan finishes his report (in italics): In the wake of the Chronicle’s story, a handful of other publications covered Grasso’s objections, arguably bringing undue attention to a relatively minor protest. This was, after all, a debate that primarily unfolded on Facebook. Nevertheless, the story still stands out, if only because it speaks so richly to the very issues Bechdel’s book explores. Stories about Grasso’s complaints offer little indication as to how he determined that the book’s content “was insensitive to people with more conservative beliefs” [without apparently reading the book]. While the book does include brief representations of graphic sex, it can hardly be described as pornographic. Grasso and his peers express little interest in this fact, apparently objecting to the mere representation of homosexuality. It is the very idea of gay sex that shocks, and it must be ignored at any cost. This is far from the first time that Fun Home has been taught at Duke. Gerry Canavan, now an assistant professor of English at Marquette University, included the book in a Duke summer course called “Comics as Literature” while he was a graduate student there. “I would say it was very well received,” he wrote to me, “one of the more popular books I taught that summer.” He claimed that he’s never received flak from students about his decision to teach the book, even at Marquette, which is a Catholic school. (Founded by Methodists and Quakers, Duke is now a nonsectarian institution.) Having taught Fun Home at both secular Cornell and Catholic Georgetown, I’ve shared Canavan’s experiences, finding that students welcome its various challenges. Describing a scenario that squares with my own experiences, Canavan observed, “students understand that” even the book’s most graphic moment “is not remotely gratuitous, but a key part of how the story is told.” Grasping this, however, means actually reading the book, and recognizing how its puzzle-box-like chapters interlock. Students like Grasso do themselves a gross disservice when they simply flip through the memoir in search of objectionable content. Ultimately, these failures of understanding reflect the book’s central dilemma all too well. Unable or unwilling to come to terms with his sexuality, Alison Bechdel’s father, Bruce, lives his life in fragments, experiencing the objects of his desire—and his desire itself—piecemeal. Alison, by contrast, works to put those pieces together again, struggling to understand the shape of her father’s life even as she traces the contours of her own. Grasso and his peers imply that they’re being bullied when they’re encouraged to read Fun Home. But when they refuse to engage, they’re not really pushing back, they’re hunkering down. Much like Bruce in one of the book’s most famous sequences, they’re choosing to live their lives in narrowly circumscribed circles, willfully blind to the stories unfolding around them. RCH: I did a long review of Fun Home in Opus 197. At the time, December 2006—and still today—I think it is one of the best, most literate and complex, deployments of the resources of the comics medium.

MAD’S GAINES WOULDN’T DESIST The following article by Comic Book Legal Defense Fund contributing editor Maren Williams appears here, verbatim; forthwith—: “Our readers undoubtedly know about EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines’ valiant defense of comics at a 1954 Senate hearing investigating whether the funny books were leading children into a life of crime. Now a recent feature at Mental Floss is highlighting how Gaines and co. continued to antagonize federal authorities–namely the FBI–during the glory days of Mad magazine in the 1950s and ‘60s. “Gaines began publishing Mad in 1952 as a spoof of genre comics, but after the Comics Code Authority was instituted in 1954, he simply changed the publication to a magazine format in order to circumvent the new restrictions. [Actually, this last sentence perpetuates a remarkably enduring myth: Gaines changed Mad’s format for another reason altogether, as we recount in Harv’s Hindsight for August 2002.] That’s why, in 1957, Mad was able to publish a column jokingly encouraging readers to write J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI to “request a membership card certifying themselves as a ‘full-fledged draft dodger.’” “At least three readers actually took on the tongue-in-cheek challenge, and the Bureau was unamused to say the least. In an internal memo, an agent identified only as M.A. Jones issued a dry critique of the magazine: “‘This book purports to satirize well-known comic figures, advertising, television and radio shows, well-known individuals, etc. However, it is extremely violent in its nature. It is also of interest to note that in its satirical treatment of famous historical incidents in American history it is rather unfunny.’ “The memo even referred to Gaines’ Senate testimony, noting that he ‘claimed to be the one who introduced horror comics’ and ‘defended such publications while testifying.’ But according to Jones, Mad’s most grievous sin with the draft dodger gag was making a mockery of the FBI’s patron saint: “‘Since the misuse of the Director’s name will probably result in the receipt of many such letters as the attached three communications, and since the use of the Director’s name is certainly in bad taste, it is felt we should have our New York Office contact the Mad offices to advise them of our displeasure and to insist that there be no repetition of such misuse of the Director’s name. It is felt that the letters which are attached should not be acknowledged.’ “When the New York agents made their visit to Mad, both Gaines and editor Al Feldstein were conveniently out of the office. The agents spoke instead to art director John Putnam, who assured them that ‘ridicule, harassment or harm was the last thing in the world intended for the Bureau or Director Hoover.’ Putnam promised that Mad would not misuse Hoover’s name again, and Gaines followed up with a letter of apology on January 2, 1958. “Of course, Mad was in fact back at it again before too long. The March 1960 issue featured a spoof ad combining Hoover’s name with that of a popular vacuum cleaner brand: The Honorable J. Edgar Electrolux. M.A. Jones, apparently on permanent assignment to the Mad beat, sent out another internal memo noting with indignation that: “‘Obviously, Gaines was insincere in this promise [not to mock Hoover] since his magazine has again placed the Director in a position of ridicule and it is felt we should once more contact Gaines or another official and firmly and severely admonish them concerning our displeasure at the tasteless misuse of the Director’s name.’ “In 1961 Mad again displeased the Bureau by encouraging readers to complete a ‘writing exercise’ and anonymously send it to local newspapers. The exercise began innocently enough, but ended with a demand for ‘$25,000 in unmarked bills.’ Once again a few naive readers actually carried out the task, and once again M.A. Jones wrote a memo. After an overview of the FBI’s previous contacts with the magazine, Jones finally concluded that repeated upbraidings were not having the desired effect: “‘An official of this magazine was contacted by a Bureau official in December, 1957, to protest a tasteless reference to the FBI and despite assurances given at that time, they have continued to publish slurring remarks about the Bureau. In view of this situation it was deemed useless to protest all such irresponsible remarks to a magazine of this poor judgment and capriciousness.’ “Although the FBI’s humorless and prissy reaction to Mad is certainly amusing in itself, it also provides an illuminating reminder of the value of freedom of the press—even and perhaps especially for satirical publications, which often tackle hot issues long before the mainstream media takes them on. The fact that Gaines and others on staff apparently had extensive FBI files is certainly a bit concerning, but even the Bureau ultimately had to admit that there was no way for it to stop ‘tasteless’ publications from seeing the light of day.” Help support CBLDF’s First Amendment work by visiting CBLDF’s Rewards Zone at cbldf.com, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF! Contributing Editor Maren Williams is a reference librarian who enjoys free speech and rescue dogs.

AMONG THE THINGS WE HAVE TO BE ALARMED ABOUT After a July/August “double issue,” the September Playboy is a disaster. First, we must acknowledge that “double issue” does not mean an issue exactly twice the size of a normal issue: the July/August manifestation toted up 156 pages; normal issues of late run 126-150 pages. So a “double issue” should, by all rights, be 250-300 pages. But that’s not happened since Playboy went lately to a couple “double issues” a year. The most we can say is that a “double issue” comes equipped with two Playmates. But the September issue, with 126 pages, isn’t a disaster because of page count. It was a disaster because it is astonishingly shy of the usual allotment of cartoons. Most issues over the last couple years have 6-8 full-page cartoons, plus 7-10 small cartoons—almost without regard to the issue’s total page-count. The ratio of cartoons per page is usually 1/25-30 full-pagers (that is, one full-page cartoon for every 25-30 pages); 1/17-22 for smaller cartoons that appear in the back of the book. The ratios in the July/August “double issue” are 1/22 (plus an Olivia pin-up cartoon) and 1/17. (And there was a special 2-page spread of eight cartoons commemorating Phil Interlandi, which I’m not including in the calculation because it’s “extra”—i.e., not usual. The spread is clearly a money-saving maneuver: Playboy will doubtless pay Interlandi’s heirs a reprint fee, but that is nothing like the cost to the magazine of first-publication.) Now, the disaster. In the September issue, there are 7 full page cartoons but absolutely no small cartoons. None. The full-page ratio is 1/18. And there’s no Olivia. This is disastrous, need I mention, because Playboy is one of the last two magazines in the country that regularly publishes cartoons—and, in fact, it makes cartoons an integral part of the publishing philosophy. The New Yorker is the other. So is Playboy abandoning its cartooning tradition—a tradition fostered by its founding editor/publisher, Hugh Hefner, who is himself a notoriously frustrated cartoonist? We fervently hope not. Despite the miserable showing in the September issue, cartooning seems otherwise alive and well at Playboy. The magazine has discovered a couple new cartoonists over the last year or less, so why would it foster newcomers if it’s contemplating throwing all the drawn pictures overboard? Nathan Greno is one of the new arrivals (since sometime in 2014, I believe). When not drawing distinctively bold-lined pictures for Playboy, Greno is a director, story artist and writer at Disney, his most visible product to-date, “Tangled,” of which he was co-director. (That is, that’s what he’s doing if the Playboy Greno is the same guy as the “Tangled” Greno, and all evidence points to his being one and the same.) The

other new arrival is Clive Collins, a British cartoonist, who freelances

all over the world from his studio in England. Here are samples of cartoons by

each. Several of Playboy’s new cartoonists over the last dozen years or so have been Europeans. But every recent issue usually includes the traditional crop of Americans— Gahan Wilson, Eric Erikson, Doug Sneyd, Don Madden, and Marty Murphy in the full-pagers (and they are in virtually every issue, so there’s not much room in the typical allotment of 5-7 cartoons for newcomers); P.C. Vey and Milt Greberg (fugitives from The New Yorker), and Don Orehek in the small cartoons at the back of the book. And these guys have been around for a long time. I remember on my only visit to Playboy’s offices to peddle my cartoons in the late 1950s, the guy I showed my portfolio to remarked that their stable of cartoonists was pretty elderly, and they were looking for younger cartoonists. At the time, I was about 21. Gardner Rea, on the other hand—one of Playboy’s regulars in those days—was 66 and would die at 72. If Playboy plans to persevere in its life-long championing of the magazine cartoon genre, it’ll have to start doing some pretty enthusiastic recruiting soon. The New Yorker has been doing just that and has lately added a couple dozen cartoonists to its roster of regulars.

OUR TIME HAS COME Time magazine, which has not been notably supportive of the emerging artistic status of cartooning, is finally coming around. Sort of. This conversion doubtless began around the corner with laddie magazines, which specialized in pages offering numerous short articles and thumbnail illustrations on a variety of subjects, no article ever continued beyond the page. Playboy has turned the first half of the magazine into laddie imitations, cramming paragraph treatment of subjects and graphics onto page after page. And Time, not to be too far behind the trend, has launched “The Brief” and “The View,” the opening sections of the magazine that, like Playboy only slightly less so, are sprinkled with short articles and graphics. All these efforts are cowtowing to the short attention span of “today’s reader,” who, we assume, is in that highly desirable demographic ages 18-35, a demographic widely assumed to be averse to reading. So magazines, which, once upon a time, aimed exactly at readers, have re-tooled for the 21st century wherein readers are hard to find. Their pages a littered with graphics—diagrams and lists and percentages and charts and snapshots and decorative pictures. Part

of the re-tooling at Time is the invention of the “chartoon.” This

portmanteau word is made up of “chart” and “cartoon.” At last, “cartoons” have

made it into Time. Here at your eye’s elbow are some samples, all

produced by John Atkinson at Wrong Hands. I’m not convinced that the “chart” part is an accurate description of the device. Charts usually compare things—sizes, durations, and so on. None of these examples do that. Some of them are pretty good “cartoons” though. But some could be funny without the pictures—Procrasti-nation (we don’t really need a map although it adds a little something cute to the concept) and Phonetically Defined (again, the pictures add a dimension but the comedy resides mostly in the words alone). On the other hand, Vintage Smartphone would fail without the pictures demonstrating what, say, a “service provider” is. The humor is in applying today’s terminology to the antique appliance depicted. (But you knew that, right?) Reality Tale, however, is just a comic strip. No chart involved. Not even a pretend chart. Still, it’s nice that the art of cartooning has advanced enough to be a vital element in Time’s approach to the non-reading customer. But

we shouldn’t be surprised. Time, like many modern print productions—even

newspapers—some time ago joined the trend to the appease Yup—as I said, the art of cartooning has achieved cultural status enough to appear somewhere other than on the funnies page of your family newspaper. Bravo.

And Speaking of Time— MARVEL GETS 6 PAGES IN THE SEPTEMBER 4/7 ISSUE (A Double Issue with Stephen Colbert on the Cover) The long article by Eliana Dockterman (who, I take it, is a reporter of the female persusasion) extols the company’s on-going and successful effort to inject diversity—gender and minority races/ethnicities—into its superhero comic books, pointing out that Captain Marvel and Thor are now female and Spider-Man and Captain America are now African American. Other superheroines have lately acquired their own titles—Spider-Gwen, Ms. Marvel (who is now a 16-year-old Muslim), and Black Widow (whose super power, Dockterman observes, is “resistance to illness and aging”; how do you attack a villain with either of those?). Among Dockterman’s statements I highlighted are these: Sales of Marvel comic books in comic book shops reached $186 million last year, up 8% from 2013. The debut issues of four of Marvel’s female titles (Thor, Spider-Gwen, Princess Leia and Ms. Marvel) each sold over 200,000 copies, “or more than double the typical number for so-called event titles.” In 2014, women made up an estimated 37% of Marvel Comics’ fan base, up from 25% only a year before. A Publishers Weekly survey of comic-book retailers this year concluded that women ages 17- 30 are the fastest-growing demographic in comics. This year’s Sandy Eggo Comic-Con, “an event that was once dominated by fanboys, now has close to a 50-50 split of male and female attendees.” And you can find women in abundance, roaming the halls in the costumes of their favorite comic book characters. “One of them,” Dockterman reports, “came dressed as Thor and was swarmed by photographers and bloggers. ‘What does it take to be Thor?’ one asked. Hoisting a foam hammer, she replied: ‘Ovaries.’” In an overt attempt to appeal to this new reader, superheroines no longer wear skimpy uniforms; instead, their duds are practical. And Marvel’s rival is joining the crusade: “When DC Comics put Batgirl, a Ph.D. candidate, into yellow Doc Martens instead of heels, the shoes sold out at a major online retailers within hours.” And yet only one of the 10 film projects Marvel has announced for the next four years—“Captain Marvel”—stars a woman, “and it won’t hit screens until 2018. DC’s much discussed ‘Wonder Woman’ movie will premiere a year earlier.” Marvel’s editor-in-chief since 2011, Axel Alonso, “acknowledges the criticism over Marvel Studios’ heavily male tilt,” but he has his eye on the comic books as the laboratory in which future movies are born. He “believes Marvel Comics will help bring about change in its role as an incubator for new movies. ‘We are responsible for building and occasionally breaking things,’ he said. ‘If something works that’s an indication for how movie audiences might respond.’” And movies, as we all know, are the Big Kahuna for comic book publishers. “Disney recorded a 22% surge in net income last year, largely due to Marvel’s “Guardians of the Galaxy.” Jerry and Joe—what hath you wrought?

And, yes, Time’s double issue, unlike Playboy’s, is, at 120 pages, twice the size of most issues, which come in at around 60 pages.

THE STORY OF JOE HILL Joe Hill became famous around the world after a Utah court convicted him of murder in 1915. According to various Web sources, even before the international campaign to have his conviction reversed, however, Joe Hill was well known in hobo jungles, on picket lines and at workers' rallies as the author of popular labor songs and as an Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, known as “Wobblies”) agitator. As an immigrant worker frequently facing unemployment and underemployment, Hill became a song writer and cartoonist for the radical union. His most famous songs include "The Preacher and the Slave", "The Tramp", "There is Power in a Union", "The Rebel Girl", and "Casey Jones—the Union Scab", which express the harsh but combative life of itinerant workers, and call for workers to organize their efforts to improve conditions for working people. Thanks in large part to his songs and to his stirring, well-publicized call to his fellow workers on the eve of his execution—"Don't waste time mourning, organize!"—Hill became, and he has remained, the best-known IWW martyr and labor folk hero. Pag Bagley, the editoonist at the Salt Lake Tribune since 1978, is producing a serialized graphic biography of Joe Hill. The rest of this article is a note from Bagley (in italics): The week of August 31, I will be serializing the life of Joe Hill in my usual editorial cartoon spot. There will be six installments that narrate the Joe Hill saga from his childhood in Gavle, Sweden, to his execution in the Utah State Prison in Sugar House 100 years ago. The first thing I did was toss out the idea that this would be unbiased narrative. "Joe Hill: His Story" is told from Hill's point of view and is unapologetic in prosecuting his claim that he was railroaded by Utah authorities. I can't help but identify with Hill. He is best remembered as a song writer who influenced major American singers from Woody Guthrie to Bob Dylan, but he was also a cartoonist with a wicked sense of humor. It was easy to crawl into his skin. I suppose if Hill had killed the grocer, John Morrison, and his son Arling, that might dampen one's admiration for the man. When he was being tried for his life, the prosecution did everything it could to portray him as a thug inclined to serial criminality — someone capable of cold-blooded murder. In fact, the only solid thing they had on him was a single arrest for vagrancy in San Pedro, California. In his songs, cartoons, letters and interactions with others, he always seems so full of good humor. He poked you with wit, not a knife. To me, anyway, it was apparent he wasn't a killer, and recently discovered evidence seems to bear that out. I

have never done anything like this before, and admit to being anxious about the

outcome. What is apparent right off the bat is that I've adopted a style for

telling the Hill story different from my usual style. I can't account for this.

It just feels right. Besides my graphic retelling, the Salt Lake Tribune will also be running a series of in-depth articles about the labor organizer in the run up to the Joe Hill Centennial Celebration at Sugar House Park on Saturday, September 5. It's gripping stuff.

RCH: To follow Bagley’s Joe Hill story, visit sltrib.com/opinion/bagley/

ODDS & ADDENDA McDonald’s and Coco-Cola have a new commercial on tv in which the actors speak in speech balloons. They open their mouths, and a balloon is emitted, making a mildly disgusting “bulup” noise as it balloons out. Words then show up on the balloon. ... The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran’s book of “wise sayings,” has animated many an undergraduate’s mental and moral processes and is scheduled to be itself animated. ... The Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco is closing on September 12 after 14 years at the Mission Street location; it expects to re-open when it’s found a new home with more reasonable rent. ■ According to a list passed out by my friend Kevin Robinette at his presentation during the Denver Comic-Con last spring, there have been 138 movies based on comics characters in the last 25 years. From “Captain America,” “Death of the Incredible Hulk,” “Dick Tracy,” and “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” in 1990 to “Antman,” “Kingsman: The Secret Service,” and “Fantastic Four” and others of the ilk in 2015. ■ In 2009, editoonist Robert Ariail resigned from cartooning at the State (Columbia, SC) because the paper cut his job to half-time; he’d held the position since 1984. In July, the State announced that as part of “an ongoing initiative to strengthen print and digital coverage” it was restoring the staff position to full-time and invited Ariail to return. He’s back, the dailycartoonist.com reports, drawing 5-6 cartoons a week, half on national/international in topics, half on local South Carolina concerns. With Ariail’s return, the number of full-time staff editoonists in the U.S. stands at 51. Matt Davies and Bill Day also have recently found full-time staff jobs, so maybe the future is no longer as grim as it was a couple years ago. ■ This year’s Best of the West award for editorial cartooning went to Jack Ohman of the Sacramento Bee. The award honors those in the Western United States for journalistic excellence and promoting freedom of information. Regarding Ohman’s cartoons, the judges wrote: “Masterfully conceived and expertly rendered, Jack Ohman’s work reflects a cartoonist at the top of his game.” Ohman is also one of the best caricaturists working as an editoonist. Second and third place went to Pat Bagley (Salt Lake Tribune) and David Fitzsimmons (Arizona Daily Star). All three cartoonists are represented in this posting’s Editoonery review of recent editorial cartoons. Each of them consistently produces hard-hitting commentary in the best metaphorical imagery of the medium.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES & MOTS From Punch cartoonist Oliver Herford: "A woman's mind is cleaner than a man's: she changes it more often.” "If you want to sacrifice the admiration of many men for the criticism of one; go ahead, get married." "Many are called but few get up." "Only the young die good." "Tact: to lie about others as you would have them lie about you." "What is my loftiest ambition? I've always wanted to throw an egg into an electric fan." "The Irish gave the bagpipes to the Scotts as a joke, but the Scotts haven't seen the joke yet."

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

TAKING ADVANTAGE of the nation’s latest reality tv show, the 2016 Presidential Race, DC has launched Prez, a nothing-is-sacred parody of American politics and the viral world. Writer Mark Russell’s technique is to hold up to ridicule virtually anything he can think of in our tv- and-social-media-dominated society, taking a quick shot and then moving on to the next target. Set in 2036, the first issue begins with Senator Thorn meeting with “a powerful group of senators” to pick a presidential candidate for their party. They pick “Gary Farmer, not the sharpest gopher in the woodpile but a good Christian man.” Take that, Tea Baggers. The America of 2036 is “hyper-conservative,” observed Chancellor Agard, writing about Prez at his blog: “Corporations can run for public office because of a constitutional amendment that declares them to be people. And you have to pay extra at the hospital for an ad-free experience.” After our encounter with Senator Thorn, we meet our heroine, Beth Ross, a teenager who, while working at Li’l Doggies House of Corndogs cleaning the grill, gets her hair caught in the grill—the whole greasy, sizzling episode captured on phone video and posted on the Web. By the end of the book, Beth’s hair accident has gone viral and it’s so popular that she’s being run for president (on Twitter, where all the voting takes place in 2036) by the Hacker Collective Anonymous, which uses this “viral Internet personality”—Corndog Girl—to protest a general lack of interest nationwide in the election. As this issue concludes, no candidate gets enough votes to be elected—although Corndog Girl wins Ohio—so the election goes to the House of Representatives, where each state gets one vote. Beth is one of the three candidates. At a secret meeting, CEOs of powerful businesses contemplate the dilemma. Says one: “It doesn’t matter who’s in charge. All we need from the government are cops, jails, and debt enforcement. The rest is cherries jubilee”—adding, a panel later, “You shoot a skunk in the road so you don’t have to shoot it on the porch,” a thoroughly meaningless statement in the context but an echo of the U.S. policy in the Mideast. That’s the kind of satire Russell manufactures: he takes shots, one after the other, creating a scattergun approach to ridicule of every aspect of our big-business-capitalistic-political-corruption-election system. The scattergun method is provocative but not particularly coherent: the shots do not focus on a particular target long enough to constitute anything more than a comical jab in the ribs. In one of the two complete episodes in the book, the satire is more concentrated and effective. Senator Thorn is interviewed on tv by Amber Waves (nifty name), a beauteous blonde, who announces that the topic is the food stamp reform act. Thorn is opposed to the food stamp program because we can’t know for sure that the recipients “aren’t using our tax dollars to support their laziness, or, worse, their drug habits.” We can hear GOP ringing in the rafters on this one. Thorn proposes an alternative that won’t cost tax payers anything—Taco Drone. Drones will deliver tacos to the poor—and they’ll also deliver “fashionable Taco Drone apparel,” emblazoned with Taco Drone sales slogans. Thus, the poor will be turned into human billboards, and the Taco Drone largesse paid for out of the company’s advertising budget. At the same time, the Drones will watch for evidence of those who “cheat the system or abuse drugs. They’re like a restaurant, a social worker and a responsible parent—all rolled into one,” says Thorn, smugly. When Thorn’s opponent on Amber Wave’s tv program, presidential candidate Tom Downey, says, “You’re turning America’s social safety net into a surveillance program,” Thorn responds: “This isn’t about surveillance. It’s about freedom. Taco freedom.” It’s a well-wrought parody of the usual political gobbledegook in which discourse abandons logic to leapfrog from talking point to talking point, blithely ignoring the absence of rationale thought in the conviction that if you say it often enough, people will believe it (even if it’s an outright lie), a situation with which our system these days is rife. Russell thinks of his comic book as science fiction. He wrote most of the next stories months ago, before the current Presidential Campaign began. But the present has intruded into his science fiction. Besides, Russell also has concerns about the present. “Th spaces of private reflection and private thought are getting smaller and smaller,” he told Agard, “—because we’re constantly bombarded from social media and targeted ads and digital media. We’re constantly being informed about an agenda that’s not our own. Our consciousness is constantly in a state of being hijacked. I really wanted to make the point that, if taken to its natural conclusion, does this mean you’re gong to have to pay extra when you go to a hospital to have an ad-free experience?”—a practice already in place. Throughout,

the energetic artwork, penciled by Ben Caldwell and inked by Mark

Morales, is purely delicious. Crisp and streamlined and laden with

computer-generated imagery. A thoroughly modern comic book. Beth Ross, the ostensible protagonist, appears only occasionally. But in her absence, we witness a lot of fun-loving satirical barb-throwing. Beth isn’t the first teen president at DC Comics, according to Agard: In the 1970s, Joe Simon and Jerry Grandenetti created Prez: First Teen President. The series lasted only four issues, but Prez Rickard showed up again in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman and in Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Strikes Again. And he’ll be back in this series, too—as Beth’s vice president. In Prez No.2, Beth wins the Presidency due to the political chicanery in the House whose members use her as a pawn and therefore lose the White House for their candidates. In No.3, Beth takes office and confounds Washington politicos by her cabinet appointments.

DARK CORRIDOR No.1 offers two stories in what creator writer/artist Rich Tommaso conceives as an anthology series, the title serving as an umbrella like “The Twilight Zone.” In the first story, “Red Circle,” a hit man follows a suspiciously bloody dog to the scene of a crime where he finds a man and wife, murdered. He also finds a lot of swag—cash, weapons, and jewelry. He phones a couple friends to come over and, in the story’s complete episode, they divvy up the loot. As they leave, one of the friends, a former cop now working as a security guard, notices that the corpses have teeth marks on their necks. Did the dog do the killing? After they leave, a woman dressed in black shows up, treating the dog as if it is hers—and as if it has completed an assignment she gave it. She takes the dog home. So is the dog a trained assassin? Find out next issue. The second story is introduced under the heading “Seven Deadly Daughters,” but the tale is entitled “Greatest Hits, Chapter One: Marie Castella.” Two cops (with the picturesque names Cosh and Bludgeon) question a man dying in the hospital, and he tells them a story about how, years ago, he killed another crook on a dark road as the two approached each other on motorcycles. He’s now dying of bullet wounds inflicted by a woman cyclist who, meeting him on a dark road, shot him as they passed each other—in a perfect re-enactment of the crime he’d committed years ago. She is wearing a jacket with the number “7" on it, so we assume she’s one of the Seven Deadly Daughters. And her shooting the other motorcyclist is an act of revenge: the first cyclist shot as the motorcycles pass each other on a dark road is Dom Castella; so we assume she is Marie Castella, the daughter. In an afterword, Tommaso tells us that the Seven Deadly Daughters are seeking revenge on the mob. The “dark corridor” involves mobsters and crooked cops. Each of the stories is a complete episode in itself. And both the stories in this title are merely the opening chapters in longer tales, and my guess is that the longer tales will intersect and overlay each other. The girl with the dog in the first story is probably another of the Seven Deadly Daughters; and the three thieves of the first story show up briefly in the second.

THE DRAWINGS of J. Bone have always appealed to me—bold lines in a simple, cartoony manner—so when Sparks Nevada, Marshal on Mars came out, I picked up a copy, the second issue as it turns out, which put me part way into “The Sad, Sad song of Widow Johnson, Part Two.” Presented as if it were a tv show for kids, this chapter is missing the Widow Johnson altogether; instead, we see Sparks in pursuit of—what? Her kidnapers? He is accompanied by some friendly Martians, blue ant-like creatures with antena, and throughout, we are bombarded with endless choruses of witless banter like this: “Great. A no-win situation. I hate these. You know why?” “Because you can’t win.” “Because you can’t win.” Tedious stuff. But these are the concoctions of the writers, Ben Acker and Ben Blacker (Acker and Blacker? Neh), who’ve produced a comic book full of activity and action and, as I say, witless banter but not much else. It would help if we caught sight of the Widow Johnson. But, no.

I enjoyed seeing Bone at work again, but I don’t think I’ll spring for the next issue of this one.

THE EPONYMOUS PROTAGONIST of Chris Warner’s Barb Wire is a bar-owning bounty-hunting blonde beauty who operates in Steel Harbor, “scrap yard of the American dream.” Mostly, the population—and the patrons of her bistro—are tough, giant-sized muscled macho guys, intent on establishing their masculinity by bravado and fisticuffs. They meet their match in Barb Wire, who doesn’t like to be called “babe.” The first issue is about brawling, which goes on from start to within a couple pages of the finish, whereupon Barb goes to her office and contemplates the bar’s financial status. The dialog bristles with terse tough talk like this: “Stormblud? That’s not a badass—that’s a freight train with a drinking problem.” Or, when the cops show up, “Start passing out cuffs,” says the top cop, “—arrest anything with a face.” Two completed episodes capture the essence of the title. In the opening sequence, Barb captures a bail-jumper, establishing her tough talk and fighting bonafides; and then there’s the central brawl in her bar. That displays macho by the cubic yard, and Barb is not very effective in quelling the mayhem (odd, considering her earlier achievement at combat). Every page screams macho macho macho. Not my cup-of-tea. And

the artwork, penciled by Patrick Olliffe and inked by Tom Nguyen, is

just as muscular and hard-bodied. Bold lines, heavily shaded and feathered. A very good first issue all around, but macho brawling is not to my taste, so I won’t be back.

LOBSTER JOHNSON

is another favorite of mine, so I grabbed the one-shot, “A Chain Forged in

Life,” by Mike Mignola and John Arcudi, drawn by Troy Nixey, whose drawing, while shadowed and feathered realistically, verges on the cartoony.

And that suits this story, which focuses on some bumbling robbers who kidnap a

sidewalk bell-ringing Santa Claus as they make their getaway. The story is told

from Santa’s point-of-view, and Lobster Johnson isn’t much on view: he shows

up, wreaks havoc among the robbers for a couple panels, then disappears. Then

he shows up again and disappears. And again. Always briefly. The robbers are

thoroughly spooked by this behavior, and by the end of the story, Lobster’s

settled their hash, and Santa is drunk. I’m up to No.5 in Eight, one of those time-traveling tales, this one switching from past to present to future to “the meld,” which is “something else again.” The story by Rafael Albuquerque and Mike Johnson isn’t quite as confusing as time travel tales usually are—I can actually tell where I am and understand the implications of the characters’ actions (a first for me with time travel tales)—but it’s Albuquerque’s art that engrosses. His forms are chiseled with sharp corners delineated with bristly feathering effects. Nicely done. Josh, the central character, has been sent on a mission to the future (or the past—I forget) in order to kill the villainous Spear and thereby change life in the present (?), and by the end of this issue—the end of Book One—Spear is dead. Now comes the confrontation between Josh and the heroine, who is resisting being his wife in some future (or past) life.

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS Capitalism is the best economic system, but left to run on its own accord, untrammeled, it’ll give in to unfettered greed and, eventually, devour itself. So we need government to control the impulses of capitalism. The genius of America has been in maintaining a creative tension between opposing aspects of greed/self-interest on the one hand and social order self-preservation on the other.—RCH

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution AS THE SUMMER PASSES THROUGH DOG DAYS, the important significant news of the world is largely ignored so that the so-called “news” media can focus myopically on The Donald Trumpet and the sensations his bloviating creates. The actual nuclear agreement with Iran goes mostly unexamined: we get, instead, endless airing of pro and con opinion about the Iran deal, most of it not based upon any reading of the agreement. In Congress, Republicons had decided against the agreement before its provisions were published. Plus outright lies and misrepresentations. Does Iran get 24 hours or 24 days to hide evidence before its nuke facilities are inspected? How easy is it to hide such evidence? Not easy at all say some: nuclear material leaves a trace that can scarcely be eradicated even in 24 days (sometimes, even 24 or more years). New York’s Democrat Senator Chuck Schumer decides not to support the treaty, and the New York Daily News gives him credit for “putting principle over politics.” What a joke. Schumer may indeed have principled reservations about the agreement, but he also has an eye on the Jewish voter in New York, who, he suspects (with good reason), is sympathetic to the Israeli opposition to the deal. But I haven’t seen any mention of this “principle.” And where’s that conversation about race that we’re supposed to be having? Meanwhile, to the vast amusement of us all, the first alleged “debate” among candidates for the Republicon Prez nomination is examined in minute detail. Who won? Who lost? Why? Trumpery was on display in all its glory at the first debate. Trump is the epitome of a Tea Bagger —a proud, egotistical blowhard, Trumpeting his brains out for all of us to see, whereupon we notice that it’s all opinion with no fact, no plan, no nothin’. And no manners: his rude buffoonery gives politics a bad name (or, rather, a worse name than it already has); he’d be a caricature of a Tea Bagging politician if he weren’t in earnest. Well, he’s still a caricature of a Tea Bagging politico. The Fox questioners were good: their questions, if not sharp (and most were), were at least pointed. At The New Yorker, Amy Davidson correctly saw the debate as another reality show on tv. And we’re due to get another dozen or so of them. On the August debate, Davidson’s report included the following perceptive interpretations (in italics): Cruz was more like a lava lamp. He seemed so oleaginous as he outlined hidden Iranian plots, and yet he has a core of fans who consider him profound. ... The G.O.P. primary race is a collection of niche candidates, and the niches are so entrenched that it is hard to imagine how they will be shaken out. There is even a semi-sensible niche, occupied in this debate by John Kasich, the governor of Ohio. He made obvious points that have eluded many in his party: about not turning down Medicaid money that could help people in his state, or how, if he learned that his daughters were lesbians, his love for them would be what it always was— “unconditional.” The audience cheered for that. But it also cheered when Huckabee complained about the military trying to accommodate transgender soldiers. ... “The military is not a social experiment,” Huckabee said. “The purpose of the military is kill people and break things.” Bush, meanwhile, tried to explain who he was by citing nicknames others had given him. He boasted about being known as “Veto Corleone,” and later said, “In Florida, they called me Jeb, because I earned it.” How do you earn a Jeb? And how is Jeb going to earn this nomination? ... After the debate, Trump told Fox News’s Sean Hannity, “We had such a great crowd, and they really agreed with what I said,” which is a measure more of his gleeful shamelessness than the debate’s reality. Trump is having fun; he’s not about to leave. He’s ready to earn his Donald.

TRUMP WAS

CLEARLY THE STAR of the show. He prevailed—from the evening’s first question,

which attempted to put him on the spot by asking him to pledge to support the

eventual Republicon candidate (he obstreperously declined) to the next day’s

wrapping up, when he made his now-infamous remark that Fox News anchor Megyn

Kelly was out to get him: she had “blood coming out of her eyes, blood

coming out of her whatever” (which many “deviants,” as Trump called them,

interpreted to be an allusion to Kelly’s menstrual period; I think it wasn’t; I

think Trump just hadn’t come to grips with his metaphor). “For her part,” observed syndicated columnist Kathleen Parker, “Kelly announced on ‘The Kelly File’ that she wouldn’t be responding to Trump’s taunts, and she certainly wouldn’t apologize for doing her job. In a political arena lacking same, that’s what classy looks like.” But Trump’s dubious post-debate behavior had no disastrous effect on his standing in the polls. He soared. His bizarre success in the polls has baffled many, and in The New Yorker for August 31, Eban Osnos tries to account for it. Trump’s indictments of immigrant criminality, which no statistic supports, and other similar fact-free statements reveal Trump’s “expansive view of reality.” Osnos quotes Trump in his book, The Art of the Deal: “I play to people’s fantasies. I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration—and a very effective form of promotion.” And his “success tells him that people support tone over substance.” According to syndicated columnist E.J. Dionne, “Trump has brilliantly succeeded in transforming a battle for the presidency into a reality show starring himself. ... Trump’s unique contribution has been to achieve a complete fusion of the culture of celebrity to politics. It brings to mind the mystery writer David Handler’s great line about ‘the power of positive self-delusion.’” Trump’s highly touted bluntness, Osnos goes on, appeals to audiences weary of hearing the typical politician’s “canned bullshit” (as one Trump fan put it). People like his speaking his mind, even if what’s in his mind is confused and divorced from reality. People feel betrayed by a political leadership’s constant compromises on immigration, national security and crony capitalism, said Erick Erickson at RedState.com. He appeals to “a confederacy of the frustrated,” said Osnos, “—a coalition of the fearful and the frustrated.” They’ve failed to achieve their dreams, and they blame the liberal conspiracy of the nation. For the last half-century or so, the rise of technology and trade and the accompanying decline of manual labor combined to hit low-skilled, poorly educated men, short-changing them on the American Dream. Trump’s most enthusiastic followers tend to be those with no college degree. And bigoted. His message about the mortal threat posed by undocumented immigrants appealed instantly to “white nationalists”—white supremacists and hate groups, those who see multiculturalism as code for the cause of their own increasing misfortune and political correctness as a smoke screen for depriving them of even more. And Trump is a good show. “Trump has been compared to P.T. Barnum,” Osnos said, “—but the comparison doesn’t capture his range; on the campaign trail, he is less the carnival barker than the full cast—the lion, the fire-earter, the clown with the seltzer—all trussed into a single-breasted Brioni suit.”

The Happy Harv Predicts: Trump is quickly emerging as a bully. He’s been a bully all his life. His success as a businessman and real estate developer depend upon bullying: when he walks in to a negotiation, he has the biggest bank roll, and the guy with the biggest bank roll usually dictates the terms. But bullying in politics will eventually be Trump’s downfall: as a rule, Americans don’t like bullies, and when they get to know him a little better, they’ll like him a lot less. Moreover, for every bully, there is at least one underdog. Americans love underdogs. And that passion will upset Trump’s applecart to a fare-thee-well. In the meantime, his fellow politicians—well, those on the same campaign trail whether in fellowship or not—can hasten his fall by attending to this simple precept: if you mention his name, you help him. Every candidate who, on the numerous occasions he/she is asked by reporters to comment on Trump’s latest blurt, actually does comment—in any way— on Trump’s behavior plays into Trump’s game: every such comment elevates Trump’s status to that of a legitimate candidate when he is actually just a reality tv star, behaving outrageously in order to get attention. As a strategy, this won’t work, of course. The so-called “news” media won’t let up on Trump, and they won’t let him go. He’s a sensation, and sensations are good for business: they bring eyeballs to the small screen and quarters to the newsstand. Theirs is a symbiotic relationship: he’s good for increasing the readership/viewership of the news media, and the news media is good for boosting his visibility. So the news media will continue to fawn over him, covering his appearances and outrageous utterances, feeding his immense ego, and broadcasting his fantasies and his speeches (which, Dionne points out, “are 90 percent about Trump—his feelings, experiences, feuds, grudges and, of course, genius”). And he’ll continue to be in the “news” and that will lend credence to his alleged candidacy. (I can’t believe he’s actually serious about it: I think he’s just a big kid having enormous fun, letting off steam about the adults who have been annoying him for years.) Nor will other candidates participate in any such scheme to consign him to oblivion by not mentioning his name. They don’t dare. To ignore The Trumpet would be to offend the most fanatic of the GOP base—his fervent followers, the paranoid and the sullen, the racist bigot, the immigrant hater, the white nationalist. Imagine what wondrous things could be accomplished in this country if the so-called “news” media harped on the need for restoring infrastructure and reducing the gross income gap with the same enthusiasm it devotes to Tronald Dump and his ilk.

PLAUDETS & PEEEVES Great sayings on t-shirts: I dream of a world where chickens can cross the road without having their motives questioned. [Accompanied by a picture of a chicken.] The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it. Whenever there is a huge spill of solar energy, it’s just called a nice day.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE DONALD TRUMPET was made for cartoonists. He’s a gift to them. They don’t have to work hard with The Trumpet. His very appearance inspires laughter. Ditto his blustery egocentric manner and his fatuous pronouncements. His every aspect invites caricature and creates comedy. Nevertheless,

the first order of Trumpet business among editoonists was to figure out how to

represent Tronald Dump, which from the rich vein of his ridiculousnesses to

choose for comedic enhancement. We saw a few first attempts last time. When The Trump visited Laredo on the Texas/Mexican border, he was asked if he had seen any evidence thereabouts to confirm his fears about Mexico sending its hoards of criminals across the border. “Yes, I have,” he said, quoted by Evan Osnos in The New Yorker, “—and I’ve heard it, and I’ve heard it from a lot of people.” “What evidence, specifically, have you seen?” “We’ll be showing you the evidence.” “When?” He let that pass. Osnos continued: “What do you say to the people on the radio this morning who called you a racist?” Trump: “Well, you know, we just landed, and there were a lot of people at the airport, and they were all waving American flags, and they were all in favor of Trump and what I’m doing.” He shrugged—an epic, now familiar arms-splayed gesture of helplessness in the face of overwhelming fame. “What can I do?” it says, “—I’m famous and beloved and victim of unadulterated adoration.” Said Osnos: “They were chanting against you.” Trump: “No, they were chanting for me.” Confronted by this colossal capacity for ignoring reality, what can one do? One does what The Trumpet does, as Steve Sack reveals in a cartoon at the lower left that also sports a magnificent caricature of its victim. Er, the perpetrator. Here we see The Trumpet’s campaign strategy—simply slime all your conceivable opponents. Right

wing-nuts applaud loudly (as is their wont) because what they’ve always wanted

is a spokesman who doesn’t mince words—and who spouts all their bigoted

bromides. The Trumper is their man. But the ensuing Trumpest doesn’t please all

observers as we can tell in our next exhibit. Next, Steve Benson continues the porcine imagery, depicting Donalt Rump as a male chauvinist pig with a comb-over—and attacking Megyn Kelly, the Fox News anchor who earned The Trumpet’s unrelenting ire by asking him a pertinent question during the debate. In The Trumpet’s opinion of women, judging by his conduct of relationships with female reporters/commentators and the rest of the female population of the planet, is right out of the pre-nineteenth century—stay in the kitchen and have babies galore. Going backward for our future. In his Prickly City comic strip, Scott Stantis is turning more and more political these days. The strip always deliberately had a conservative bent, but now, with the Presidential Campaign fully underway, Stantis has pulled out some of the stops. Unhappily for him, the conservative bent in the Republicon Party is now being overwhelmed by a blowhard bent. Still, as we see at the lower left, Stantis’ liberal spokesman, a coyote pup named Winslow, can’t help falling in love with Megyn Kelly. (Me, too, as I have amply intimated.) And in the strip below that, Stantis’ simpatico character, Carmen, a young conservative Hispanic girl, deals forcefully with the overweening Trumpet and his anti-woman anti-Hispanic stance.

IN OUR NEXT

DISPLAY, editoonists confront The Trumpet’s surprising triumph at the first

debate. In Daryl Cagle’s image, next on the clock, The Trumpet simply overshadows all the rest. Below Cagle, Jeff Danziger takes up The Trumpet’s obvious passion for self-promotion, creating a memorable image of just how far Tronald Dump will go to keep himself in the spotlight. At the lower left, David Horsey conjures up an image that reveals why Trump is so successful: Jeb’s thoughtful assertion to the contrary notwithstanding, The Trumpet does represent the values of the Republicon Party. In fact, in Horsey’s image, Trump personifies the values of the loudest segment of the GOP. On

the next visual aid, beginning at the lower left for a change, we have from John

Darkow the explanation that underlies Horsey’s cartoon. Then Milt Priggee perpetuates the metaphor that the crammed jumble of GOP candidates is a tiny auto full of clowns, and then, grafting another metaphor on the image, he depicts The Trumpet as a canon loosed from the comical car. In

our last foray into editoons on Trumpestan, we have one more jaundiced orthodox

view of Trumpery and a couple exposes of The Trump’s alleged political logic. The Trumpet’s recently announced policy on immigration is a spectacular example of political distraction. His understanding of the immigration “problem” is based upon erroneous assumptions and ludicrous myths rather than fact. Most illegal immigrants do not come here over the southern border. A big hunk come from Asia. And most of the immigrants who are illegal didn’t start out that way: they are illegal because they stayed here beyond the expiration dates of their visas. And these are the people—now productive workers, fully integrated into American society—that he wants to round up and deport? Not likely. Not practical either. None of what The Trumpet proposes is at all practical. Apart from the sheer impossibility of deporting all 11-plus million illegal immigrants, the wall he proposes will scarcely solve the problem. If we have a wall at the southern border, we’ll pretty soon need one at the northern border—all 5,525 miles of it (the longest border in the world)—because those who can’t enter the U.S. from the South will try at the North. But the greatest distraction fostered by The Trumpet’s immigration policy is the one Luckovich’s cartoon is about—the demand that birthright citizenship be abolished. It’s the greatest distraction because it can’t be achieved. No way. It is a political non-starter. It would require a constitutional amendment that would invalidate the 14th Amendment, and the political will for such an undertaking simply doesn’t exist. Such an amendment would first have to make its way through Congress (which is dedicated to doing nothing) and then it would have to be ratified by 38 states. Even if the Republicons controlled both houses of Congress and the White House and every statehouse in the country, it is highly doubtful that such an enterprise would succeed. But as soon as The Trumpet blew on the issue, all of a sudden, the rest of the clowns in the mini-car jumped on the notion with great enthusiasm, falling all over themselves in a rush to have an opinion on the matter. They all started talking about it—several of them supporting the idea. And the so-called “news” media persisted in asking them all questions about it. Why would supposedly intelligent people willingly participate in such idiocy? Because it’s a great distraction, and all the politicians love a distraction. Political language is the language of deception not revelation; all the talk is designed to conceal not to reveal. And a distraction suits this purpose admirably. A distraction is created by politicians who don’t want anyone to notice that they’re not doing anything. Their only concern is to be re-elected and to that end, they prefer talking about doing something to actually doing something, particularly when the thing they want to talk about doing is something that can’t, really, be done. The talk, of course, keeps the “news” media and the voting public preoccupied enough that they don’t notice that the blathering politicos are not doing anything for the good of the body politic or the country but are talking about something impossible of accomplishment. And all of our current crop of politicians—whether presently running for office or languishing until the next time their term is up—are of this ilk. Regrettably. This distraction is a great one because (a) it’s outrageously and therefore sensationally controversial so it attracts attention and (b) it can be talked about endlessly with absolutely no risk that any of the talk will come to anything. No matter how much talking is done, nothing else will be. But the author of the great distraction is getting great campaign trail mileage out of it. Phooey. The Trumpet is a fool, a buffoon, and a blowhard. He is therefore perfect for today’s politics. But a practical reality-based political leader he is not. Below Luckovich’s Native American, Gary Varvel creates a sequence that displays the flip-flopping that The Trumpet does as he changes his views to appeal to a different electorate. Finally, Clay Bennett shows just how damaging The Trumpet’s campaign is to the Republicon Party: his candidacy in the general election would almost certainly assure Hillary of a victory.

POLITICS IN

GENERAL proceeds apace. At the upper left of our next visual aid, Tom Toles offers

the usual racetrack metaphor for the coming campaign but turns it on its side

to more accurately reflect the realities of American politics these days. Finally, an antique by Britain’s Steve Bell. I found this while rummaging through an old file folder. It appeared during the 2000 Election, when Florida went for GeeDubya instead of Al Gore, hence the importance of the cartoon’s map of Florida, which became the poster child for “electile dysfunction” because counting ballots didn’t serve their intended purpose. The imagery is purely unforgettable and a perfect metaphor for the failed function of the ballot box in Florida. This was simply too good for me to overlook in this, our periodic examination of the way editoons work, Bronco

Bama, the perpetual target of GOP nonsense and mendacity, is the theme of the

cartoons in the next exhibit. At TheAtlantic.com, Peter Beinart remembers the Netanyahu of another time—2002—when he told Congress that “there is no question” that Saddam Hussein was working on nuclear weapons, and that a U.S. invasion of Baghdad “will have enormous positive reverberations on the region.” Instead, 500,000 Iraqis died, a third of U.S. veterans who served there have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and the region is in utter chaos. Why should we listen to Bibi? Hasn’t he proved that his opinions are unreliable? Back to our visual aid, where, next, Signe Wilkinson with her playlet that shows an effect of senatorial opposition to the Iran deal. As Obama said, it’s an interesting proposition to consider the American right wing in strategic agreement with the Iranian right wing. Nick Anderson is back at the lower right with the one-two punch that accurately depicts the Fox News response to any news, whether good or bad. It is also the response of the Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm in both houses of Congress. And then Mike Luckovich provides an ironic metaphorical image of just how lame the Obama administration has become in its last years in office. We’re

never far away from gun violence these days: a recent report claimed that, as of

August 26, we’ve had 247 mass murders in the 238 days of the year so far.

That’s more than one mass murder every day in this country. It’s a daily event.

And that makes editoon commentary on the topic as inevitable as Saturday

morning cartoons on the kids’ channel. And because most editorial cartooners

are liberal rather than conservative, the images they make assault the

firearmed sensibilities of the National Rambo Association. Steve Sack is next with a pictorial comment that is just as powerful—and just as horrifying. At the lower right, Mike Keefe makes a raw comment on the terrifying combination of human psychological disorder and the availability of guns. Finally, Clay Bennett nails the NRA: transporting a gun in a stretcher shows that the NRA cares more about the welfare of guns than the welfare of people. And now we’re shooting cops who’ve sworn to serve and protect us, and presidential candidates who want us to let them lead the country—and the world—blather blithely on about deporting immigrants and building border walls and other fantasies wholly divorced from the reality we’d like them to deal with. At

our penultimate exhibit, we take up some less important matters—but, still,

matters that matter some of the time to some of us. But the struggle for everyday human rights for gays is scarcely over. County clerks in the more benighted parts of our country are refusing to issue marriage licenses to gay couples because doing so would be against their religious principles. Religious principles being, in many instances, eccentric to the point of ludicrous, we can expect them to be cited for all manner of a-social behavior in future. Below Lowe’s clouds, Joe Heller marks the passing of Jon Stewart from the televised airways. Ironically (maybe intentionally), the Stewart fan is getting his news from a print medium. Then Steve Sack gets cute at the lower left, resorting to an aged axiom (“when the cat’s away, the mice will play”) to show the dire consequences of Stewart’s departure: without him belling the cat, no telling what mischief those Fox mice will get up to. (I’m not sure “belling the cat” is a functional metaphor here: a cat is belled in order to warn us of its presence, so why would we want to be warned about Stewart’s frequent demolition of Fox?) Portraying Fox News as a gaggle of mice is a nice move. Mice are more cute and playful than ugly and menacing—a good way to think of Fox: the network is not as powerful or as widely watched as it would have us believe. Any one of the broadcast networks has larger viewership. Finally,