|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 342 (July 31, 2015). It’s still our annual Open Access Month. All the usual $ubscriber walls and barricades are down, and you and anyone in your family (or neighborhood) (or country) can peruse all of Rants & Raves (including archives—sixteen years’ worth!) at leisure without having to pay a fee. If you’ve just dropped in for a visit during our Open Access Month, here’s what we do here. We talk about comics. Comics and cartooning. We love comics and cartooning and we express that abiding affection by talking about them. Sure—we report news about comics and review new funnybooks as well as serious tomes that ponder the medium and we take notice of whatever earth-shaking events are shaping the history of cartooning. And, yes, we criticize comics, denominating some efforts good and excellent; others, not so good (even bad). But these efforts are merely excuses, feeble rationales. Our real purpose here—why we do this—is purely self-indulgent: we love cartooning and talking about cartooning in all its static forms—comic books, strips, editorial cartoons, comic books and graphic novels. And that’s what you’ll find here. Talk about all these manifestations of cartooning. Liberally illustrated talk, as you’ll soon see. Until August 15, you can join us in hoppin’ down the bunny trail where, this time, we report on the 2015 San Diego Comic-Con, the New Archie, the return of Opus, a new Seuss book, Marvel’s Secret Wars, plus reviewing Rowland B. Wilson’s Trade Secrets and The People Inside (a poetic graphic novel), a new Hirschfeld book, Wagner’s failed revival of Eisner’s Spirit, the month’s editorial cartoons and glimpses of the Peanuts Tribute. And if you like what you find there, consider joining us as a $ubscriber for merely $3.95/quarter after an initial $3.95 introductory month fee. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

Copy-Catting: When It’s Not Plagiarism NOUS R US The New Archie Berk Is Back with Opus New Seuss Book Spectacular Growth in Comics Industry The Latest at Charlie Hebdo John Lewis Marches in San Diego Cul de Sac Book Gets Eisner

ODDS & ADDENDA Tom Tomorrow’s 25th Relic Salt Lake Comic Con Frank Miller’s Collaborators Named Zunar’s Trial Postponed

THE SAN DIEGO COMIC-CON REPORT Conan at the Con Remembering My First Comic-Con The Excitement Fades & Other Flaws But All Is Not Gloom Comic-Con to Stay in San Diego through 2018 Disgracefully High Hotel Room Rates

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Marvel’s Secret Wars: 1872 and Korvac Saga Matt Wagner’s Spirit Flops Starve Sex Final Issue of The Big Con Job Flops

EDITOONERY The Iran Deal Political Shenanigans As Usual Presidential Campaign Notes Trumping, Cosby, Jenner Other Issues—Iraq, Afghanistan, Gun Control

Praises for President Obama

Interview with The New Yorker’s Tom Bachtell

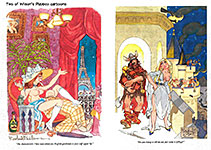

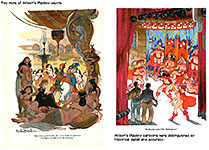

ACCRETION OF INTENTION Review of Celebrity Caricature in America

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Taboos Violated and Other Fun Stuff in the Funnies BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews/Previews of—: The Complete Cul de Sac in Two Volumes Hunter S. Thompsons Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas More Lady Killer Peanuts: A Tribute to Charles M. Schulz

BOOK REVIEWS The Hirschfeld Century Rowland B. Wilson’s Trade Secrets & Stories About Him and Me

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEW The People Inside

PASSIN’ THROUGH Leonard Starr Tom Moore Pink Flamingos

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

COPY-CATTING: WHEN IT’S NOT PLAGIARISM Before we get too far away from the incident, you’ll recall that last time (Op.341) I reported that three cartoonists seem to have ginned up comedy in ways identical to the hilarious machinations of some other cartoonists (or humorists) —in one case, by looking back more than a generation ago. You may wonder why I did not leap up and down and shriek “Plagiarist!” One of the reasons may be explained in this posting when you get to a longish review of Rowland B. Wilson’s Trade Secrets, to which I’ve appended an account of some light-fingered lapses of my own in a youth long lost. My tolerance of such thefts stems, in part, from recognizing some time-worn and therefore hallowed practices of cartoonists. Take the magazine cartoonist who often looks at book collections of cartoons, seeking inspiration—which may take shape in imitating some aspect of what he/she sees in the book. A scene, for example, might be borrowed but the caption changed. Or vice versa. Instead of a gag about a tiny kitchen the cartoon becomes a gag about crowded life in a pre-World War II submarine. Or vice versa. This practice even has an official name—“switching.” Old how-to books are full of advice recommending idea-generation by switching. And then there’s a hoary anecdote about how a bunch of roaring twenties cartoonists who lived in New York used to go together to the Palace once a week to take in the vaudeville acts. They’d sit in the front row and write down the jokes of the comedians, claiming proprietorship by yelling. The first one to yell “Mine” got to use the gag in his comic strip. Or maybe they just took turns. I can’t quite remember. I said the story was hoary. I don’t mean to endorse stealing, but I think we can get a little too worked up about borderline instances. Outright copying—line-for-line in a drawing; word-for-word in dialogue or caption—is rightly verboten hereabouts, just as your third grade teacher used to tap you on your shoulder when you were copying your neighbor’s paper, shaking her finger and telling you: “Do your own work.” Every self-respecting cartoonist must live up to his third-grade origins. But I join cartoonist Elena Steier who keenly observed that “cartoonists have a bunch of different words for plagiarism: swiping, switching, cloning, pastiches, homages, appropriation, and probably more that I haven't researched on Wikipedia.” She added that “it's like the Eskimos and their many words for snow”: the more words for a single phenomena, the more common the phenomena. “If nothing else,” she concluded, “that should tell you that everybody has higher standards than we have.” And now let’s resume our regular scheduled programming—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

The

biggest news of the season —if not the decade (or, indeed, the last half-century)—is the reboot of Archie

at Archie Comics. In mid-July, the much-touted “new” Archie by Mark Waid and drawn by Fiona Staples hit the newsstands and comic book shops. In

variant covers alone—reputed to be sixty (SIXTY!)—Archie No.1 made

history. After 75 years in the mold created by Bob Montana and

perpetuated (with sexier girls) by Dan DeCarlo, Archie now looks

startlingly different. More like a real-life teenager and less like a cartoon.

But still, not photographically realistic either—as you can see in the

accompanying visual aid. Staples is a welcome breath of fresh air. The art in many Archie titles has become somewhat sloppy in recent years; Staples tidies it up in addition to changing it. Her crisp and clean rendering—deploying a slightly flexing line with fineline accents—delineates characters and settings simply but with a convincingly. She departs dramatically from custom without destroying entirely the traditional visual ambiance. Jughead’s nose, for instance, protrudes but it isn’t the Pinocchio schnoze of the DeCarlo years. Nicely done. Waid’s story is likewise a more realistic portrayal of highschool life than we’ve had for the last 75 years. The story is provocative without being a world-shatterer. Exactly what we hoped for. We’re still in Riverdale in the all-American high school milieu. But the story in this issue does not reach a conclusion. It is “continued” into the next issue. I hope that doesn’t portend that Archie’s stories will now be multi-issue tales like the superhero books from the Big Two, DC and Marvel (neither of which has distinguished itself with inventive maneuvers). In the opening pages, Archie tells us that he and Betty, who’ve been “together” since kindergarten, have broken up over a mysterious “lipstick incident.” Their friends try to get them back together (“they’re the power couple,” one exclaims), but it doesn’t work. We learn that Archie is accomplished on the guitar and that Jughead is smarter than he seems. But at the end of the book, Archie, glum over “losing” Betty, is heroically determined to face the future without her—but, in another new maneuver, he solicits our advice at either @archiecomics or #lipstickincident. Glamorous Veronica Lodge, the other of Archie’s two traditional loves, isn’t around: just as in the initial run of the characters, she shows up later. Archie’s very first adventure, by the way, is reprinted at the end of this issue from the December 1941 issue of Pep Comics No.22. But in this re-launch, the last picture in the story is of a billboard, announcing the impending arrival of Lodge Industries, which Archie walks stoically by, musing: “Maybe there’s some amazing new girl just around the corner...” The new Jughead title, by the way, is promised in this book for October 7.

ARCHIE COMICS’ success in boldly re-invigorating its iconic characters is in sharp contrast to the never-ending timid re-invention follies being committed at DC and Marvel, each of which seems bent on revisiting the pasts of its characters by way of tinkering forever with the present. DC’s “Convergence,” which we explored somewhat last time, is a spectacular failure of imagination. And logic. The idea seems to be to bring together, for once and ever, all the loose ends of the numerous “universes” created over the years, mostly in order to embrace the picturesque characters from the past. The Convergence objective, it would seem, is to make less baffling for new readers the whole DC universe. A noble enterprise, you’d think, but the means to this admirable end requires revisiting antique characters that new readers can’t possibly know well enough to understand their import. Shelly Mayer’s Scribbly, for instance, shows up in Convergence World’s Finest No.2. Who, among the new generation of readers, knows Scribbly? Or cares enough about him to become engaged in stories about him? Only deeply engaged fanboys who know and dote on every jot and tittle of the characters’ histories. So, the way to get new readers involved is to present them with characters and allusions they can’t comprehend? Not in my world. But then, unlike the fanboy writers who produce superhero comics at both DC and Marvel, my world is not a hermetically sealed bubble of adventuring fantasies. Meanwhile, Marvel is playing catch-up. Not to be outdone by its chief rival, Marvel has launched its own effort at revitalizing its universe. We’ll take a look at a couple of the titles in this stream in our Funnybook Fan Fare department down the scroll.

BERK IS BACK On his Facebook page on Sunday, July 12, renegade cartooner Berkeley Breathed posted a provocative photo of himself bent over the drawingboard on which was a comic strip entitled “Bloom County 2015.” The accompanying caption read: “A return after 25 years. Feels like going home.” And the next day, Monday, July 13, a brand new Bloom County strip appeared on Breathed’s Facebook page. (That strip appears below, down the unrolling scroll somewhat.) It’s true. Opus the flightless flighty penguin and the rest of the denizens of Bloom County are back. Again. For a while. As usual. Breathed apparently can’t stay away. In its original incarnation, Bloom County ran December 8, 1980 to August 6, 1989. It succeeded partly because it looked somewhat like Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury and peeled off the same sort of socio-political satire, and when Trudeau took a sabbatical in 1983, vacating his spot on the funnies page for 18 months, Bloom County slipped easily into the line-up, in effect taking Doonesbury’s place. But Breathed struggled under the pressures of a daily strip deadline (which is usually met with weekly shipments). He told stories about being so late that he delivered the strip to his syndicate in person, flying across country, inking the strip on the plane. So he quit the “daily” grind and started a Sunday-only strip, Outland, thinking the reduced workload would be liveable. Outland ran September 3, 1989 to March 26, 1995. Although the strip wasn’t conceived as a continuation of Bloom County, after a while, Breathed brought Opus into the proceedings (thinking, perhaps, that reviving the popular character would inject life into Outland, which probably wasn’t inspiring much reader response; just guessing). It’s not clear why he discontinued Outland. He started producing children’s books (and I think he offered that new career as a reason for abandoning the old one). But I think that he missed the controversy and consequent fame that he had generated with the daily Bloom County. At the time of Outland’s debut, I speculated that it would not be possible to generate that sort of reaction with once-a-week appearances. With Bloom County, he’d won a Pulitzer for editorial cartooning in 1987, a nearly unprecedented occurrence. Trudeau had won a Pulitzer in 1975, but both of these awards for “editorial cartooning” upset some editorial cartoonists who weren’t at the same time, dabbling in comic strippery. Another Pulitzer winner who worked exclusively in editoons, Pat Oliphant, said that Bloom County was guilty of “passing off shrill potty jokes and grade-school sight gags as social commentary.” In any case, after eight years out of the funnies, Breathed, undoubtedly missing his old life in the arena, launched another Sunday-only strip, this one starring the perennial penguin, Opus, that ran from November 23, 2003 to November 2, 2008. In a move to improve the over-all comic strip venue, Breathed demanded that newspapers who signed on for Opus give the strip a half-page, which he promised he’d fill with outstanding color paintings, and in demanding this concession, he made some snide remarks about other comic strips (chiefly, those no longer being produced by their originators). I didn’t think his product lived up to his extravagant promise: Breathed’s Opus was not Harold Foster’s Prince Valiant no matter how high-fallutin’ Breathed’s prognostications. But he kept at it for 5 years. Again apparently losing interest, perhaps because the weekly exposure didn’t generate enough excitement. (I realize I may be doing Breathed a disservice in such pronouncements. But he seems a little fickle, and it’s pretty clear that he enjoys the fame and the fussing. It’s also clear that he loves cartooning.) So what is bringing this prodigal son back to the farm once again? Michael Cavna wanted to know and asked Breathed. To which Breathed said: “Opus’s [voice] came screaming back at me — true— when I faced those four empty panels that I hadn’t done since 1989,” he said (ignoring the fact that he’d done a Sunday comic strip for a total of ten years years after 1989). Elsewhere (to Dave Itzkoff at the New York Times), Breathed elaborated a little: “Deadlines and dead-tree media took the fun out of a daily craft that was only meant to be fun,” he said, glibbly. And then he blamed his absence on the zeitgeist: “I had planned to return to Bloom County in 2001, but the sullied air sucked the oxygen from my kind of whimsy. Bush and Cheney’s fake war dropped it for a decade like a bullet to the head. But silliness suddenly seems safe now. Trump’s merely a sparkling symptom of a renewed national ridiculousness. We’re back, baby.” For the time being, Breathed intends to produce Bloom County only online, at his Facebook page. No deadlines, just having some fun drawing the characters he invented (and loves). Cavna pressed him for more, and he gave more, which Cavna prefaced with a short apostophe about comic stripping (here, in italics)—: When I hear from Breathed, he speaks of a “joy” that can become flattened — like a soda without its fizz, with no buoyancy in its (word) bubble. There is the pressure of sustaining your popular creation, even as page space and audience both shrink for most print newspaper cartoonists. You get into this business of comics for sheer fun, and sometimes the fun is leeched by comics becoming a sheer business. Cartoonists are usually one-person studios; if the pressure is too great and you can afford to walk away, you likely might, and do. But what if the deadlines are removed, and you don’t worry about sustaining a massive audience, and you can pick and choose your spots to create when the spirit and digital brush are willing? To which Breathed responded: “The option of self-publishing allows for the freedom that will keep it fun, which it can’t stray from — or forget it,” Breathed told Cavna about posting Bloom County where and when he desires. “Dead-tree media requires constancy and deadlines and guarantees,” Breathed continued. “This flattens the joy [like taking the fizz out of a soda]. It also presents a huge income. It’s an interesting trade-off, isn’t it?” Cavna commented: “Yet if your long-dormant characters can still turn a side profit while you create gorgeous children’s books and explore other projects, the trade-off can well be worth it for the midlife artist.” Breathed went on to tell Cavna that “much of the past two decades [has] been fallow ground for whimsy,” then acknowledged that was a “glib” answer. “Whimsy has sprouted healthy across the Internet since Outland breathed its last word-balloon 20 years ago,” Cavna countered. Times change, Cavna acknowledged, but social media response to Opus’s return has been “massive— the stoked nostalgia burns like a bonfire.” “Honestly, I was unprepared for it,” Breathed said. “It calls for a bit of introspection about how characters can work with readers—and how they’re now absent as a unifying element with a society,” he continued, launching into a flight of philosophical musing: “There is no media [other than newspaper comic strips?] that will allow a Charlie Brown or a Snoopy to become a universal and shared joy each morning at the same moment across the country,” Breathed went on. “Maybe the rather marked response to my character’s return is a reflection of that loss. A last gasp of a passing era.” Well, maybe. But maybe Breathed is attaching to his comic strip creations a stature they have not yet earned. Charlie Brown? Snoopy? Opus may be close, but I don’t think he’s there yet. Charles Schulz, remember, kept constantly at his drawingboard for nearly 50 years, no multi-year desertions. Then again, maybe Breathed, while enjoying himself at Opus’s revival, is hoping his fans will rise up as a body and demand Bloom County’s return to the funny pages of the nation’s papers (whose editors, maybe, have had it with Breathed’s capriousness). Who can say?

A BOX OF SEUSS It’s the classic lost-and-found story. Looking in an old box in the attic, someone discovers a long lost or forgotten (or, even better, completely unknown and unforeseen) treasure. In this case, it’s poetic that the story is about a storyteller. Alexander Alter at the nytimes.com fleshes out the tale—: “After Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, died in 1991, his widow, Audrey Geisel, decided to renovate their hilltop house in La Jolla, Calif. She and an assistant cleared out his office, donating most of his valuable illustrations and early drafts to the University of California, San Diego, and stashing some doodles and abandoned sketches in a box. “It wasn’t until October 2013, when they decided to have the rest of his notes and sketches appraised, that they closely examined the contents of that box. They found a set of brightly colored alphabet flash cards, some rough sketches titled ‘The Horse Museum,’ and a manila folder marked ‘Noble Failures,’ with whimsical drawings that he had been unable to find a place for in his stories. “But alongside the orphaned sketches was a more complete project labeled ‘The Pet Shop,’ 16 black-and-white illustrations, with text that he had typed on paper and taped to the pages of drawings. The pages were stained and yellowed, but the story was all there, in Dr. Seuss’ unmistakable rollicking rhymes.” Almost all there. Upon closer examination, reported Karen Raugust at publishersweekly.com, the book needed a little work. Very little. The Random House editorial team would add a few transitional phrases after selecting the text. Geisel typically wrote first and drew second, continuing to edit the text while perfecting the pictures. On some pages of The Pet Shop, Geisel had pasted successive versions of the text, typed on onionskin paper, one over the other. Some of the pages had layers of three to four versions of text, suggesting, Raugust noted, that Geisel was still involved in the editing process. After “painstaking work and a meticulous, almost forensic reconstruction of Geisel’s creative process,” the team decided to use the top layers of text as the most recent and therefore preferred version. The book was published with a one-million-copy press run as What Pet Should I Get —the first new Dr. Seuss book since Oh, the Places You’ll Go in 1990. It went on sale in bookstores nationwide on July 28. Apart from the fact that Geisel was a cartoonist, what’s this story doing in this posting of Rancid Raves? Easy. But insidious. This is the San Diego Comic-Con report, and because the Con is a refuge for nerds as well as geeks, the inventor of the word nerd belongs here. The word first appears in Dr. Seuss’s 1950's If I Ran the Zoo. In the book, a kid rattles off a list of fantastical creatures that rival the animals found in the zoo: “I’ll sail to Ka-Troo and bring back an It-Kutch, a Preep, and a Proo,/A Nerkle, a Nerd, and a Seersucker too!” In the book, a sign identifies a “nerd” as a red and yellow and white-haired sourpuss. It appears to be the first documented instance of the word, which has since morphed into a put-down for bookish people. So there.

SPECTACULAR GROWTH IN COMICS INDUSTRY From Rich Shivener at publishersweekly.com—: Its total sales rose 10% in the first six months of 2015 over the same period in 2014, Diamond Comics Distributors announced during its annual Retailer Appreciation Lunch at San Diego Comic-Con. Compared to 2014, Diamond's comics periodical sales were up 16.5%, graphic novel sales increased 5.9% and toys, 15%. Diamond’s customer count rose 3.7%, showing small but continuing growth in the number of individual comics stores.The figures were announced by Diamond CEO Steve Geppi who added, "The growth in the comics industry has been nothing but spectacular.”

CHARLIE’S SPOILS In this month’s Vanity Fair (dated August), Roger Cohen reports that the staff of Charlie Hebdo is divided about what to do with the windfall of money the satirical magazine has been raking in since the January killings, and he portends disaster just over the hill if the staff can’t resolve “the rift over how the leftist magazine should handle its transformation from a financially troubled niche journal to a global brand enriched by tragedy.” Compounding the problem is the brand Charlie now bears as Islamophobic. “Conflate the two,” Cohen writes, “and you have a paper that has betrayed its leftist past, condoned French racism toward Muslims in its obsession with jihadist Islamism, and moved to the pro-Israel right.” Given the production schedules of monthly magazines, the article was doubtless written a couple months ago (right about the time we reported here the emerging money dispute). But on July 7, Inti Landauro at wsj.com reported that the “poison money” issue had been resolved, at least for now: “Laurent Sourisseau, the magazine’s chief editor and one of only two surviving shareholders, said all of the 2015 profit will be plowed back into the firm. The company will also change its status to one committed to reinvesting at least 70% of profit on a continuing basis, he said.” “We want to reassure people about the use of profits,” said Sourisseau, who signs his cartoons with the pen name Riss. “We will keep 100% of profits in the company this year, there won’t be dividends to shareholders at all.” Many on staff had pressed the publication’s owners to give up their shares and place the newspaper in the hands of all its employees, something that was roundly rejected at the time by Sourisseau and Gerard Biard, the No.2 editor. But the latest proposal shows an effort to meet the staff halfway. Laurent Léger, an investigative reporter who had pushed for the cooperative route, said he was satisfied by the shareholders’ commitment not to pay any dividends this year. “We didn’t want to get dividends for ourselves. What we wanted was no dividend being paid,” he said. And that’s what is happening. For now. And the issue of the magazine’s reputed Islamophobia has also been, for now, resolved. On July 18, Ishaan Tharoor at WorldView.blog (via washingtonpost.com), reported that Charlie editor Sourisseau announced that the publication would no longer publish the cartoons of the prophet Muhammad that have garnered it worldwide notoriety. "We have drawn Muhammad to defend the principle that one can draw whatever one wants," said Sourisseau, in an interview with Stern, a German magazine. But Sourisseau said that it was not Charlie Hebdo's intent to be "possessed" by its critique of Islam. "The mistakes you could blame Islam for can be found in other religions," he said. Sourisseau's remarks were foreshadowed in April by another of the magazine’s cartoonists, Renald Luzier, who drew a tearful Muhammad on the cover of Charlie’s first post-massacre issue. Luz, as he signs his cartoons, told a French cultural magazine that he would do no more caricatures of Muhammad, saying that drawing the Prophet "no longer interests me. I've got tired of it” he added, “just as I got tired of drawing [former French president Nicolas] Sarkozy. I'm not going to spend my life drawing them." Whether this should be regarded as a victory for Islamic hooligans, who express their opposition to pictures of Muhammad by killing people, is, for now, a matter of opinion. Have the hooligans silenced Charlie Hebdo on the Muslim issues that prompted some of its satire? (“Some” but not much. Most of the magazine’s targets are within the arena of domestic French politics rather than religion or persecuted religious minorities or international terrorists.) Editor Sourisseau, who survived the January attack but was wounded in the arm, maintains that Charlie will continue as before. He said the magazine will remain faithful to what it was before the attack and will continue lampooning organized religion—as well as politics. “It’s about freedom of speech, we are not obsessed with Islam,” he said.

MARCHING IN SANDY EGGO Congressman John Lewis, one of the last living heroes of the Civil Rights movement in the sixties, visited the Comic-Con to promote the second volume of his graphic autobiography, March. He told Michael Cavna that he’d been to the Small Press Expo and to Dragon Con. “It sort of changed my life,” he said. In San Diego, he joined the cosplayers, dressing as he was dressed when he and hundreds of others marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge that “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, when peaceful marchers were beaten and tear-gassed by police on horseback. Lewis found a trenchcoat like the one he wore then—and a backpack like the one he backpacked. In the backpack were the same things that he’d put there on the fateful day: two books, an apple, a toothbush and toothpaste—in case he got arrested and jailed. Missing was an orange. “We tried but couldn’t find an orange,” Lewis reported, “—in Southern California, of all places.” After making a presentation about March and what it meant to an audience that included a flock of third graders from a nearby elementary school, Lewis put on his costume and led his audience on a march through the exhibit hall to the Top Shelf booth, where he signed books. As he marched, Lewis held a child’s hand in each of his. The costumed freedom marcher leading a march, a genuine hero among the spandex-clad faux superheroes. “It just felt special,” he said. “I was in the moment. It felt like I was living a portion of my life over again.” Lewis joined the Civil Rights movement after reading a Martin Luther King Jr. comic book as a teenager. More about the San Diego Comic-Con down the scroll at Sandy Eggo Again.

CUL DE SAC GETS BEST HUMOR EISNER Cul de Sac creator Richard Thompson was awarded this year’s Eisner Award for Best Humor Publication for his The Complete Cul de Sac collection (reviewed briefly in Book Marquee below). Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com reports that Thompson’s friend and cohort Chris Sparks accepted the award on his behalf during the festivities in San Diego: “He posted on Facebook afterward, ‘Cul de Sac, the last great comic strip won the greatest cartooning award, The Eisner. The world is a happier place because of Richard Thompson.’” Thompson responded on his blog: “I want to thank the judges, everyone who voted, especially for me, and for courage in the face of wicked witches above & beyond I’d like to thank Nick Galifianakis, David Apatoff and Chris Sparks, who had to accept the Eisner on my behalf because I’m scared of public speaking and was busy that night.” Self-deprecating humor is the hallmark of Thompson’s demeanor these days as he battles Parkinson’s Disease, the scourge that drove him from the drawingboard and his comic strip.

ODDS & ADDENDA Dan Perkins (better known as Tom Tomorrow) was astonished when his Kickstarter goal for reprinting all 25 years of his weekly political cartoon, This Modern World, in a two-volume, slipcased edition reached its target in less than 24 hours, reported Gil Roth at traffic.libsyn.com—and then doubled again. Hard to understand such enthusiasm for cartoons whose value is an intense topicality that after even a few months will fade, rendering the cartoons meaningless to most readers. ... Manga marches on; Barnes & Noble is doubling the shelf space for manga in its stores. ... Writer Brilan Azzarello and artist Klaus Janson were revealed as the collaborators with Frank Miller on the third volume of the latter’s Batman series, entitled The Dark Knight: The Master Race. ■ San Diego Comic-Con is still upset by and leveling a law suit against the Salt Lake Comic Con despite the latter’s being granted recently by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office a trademark for “Salt Lake City Comic Con”; the registration was a Supplemental Trademark Registration, says Sandy Eggo, which "does not provide all the protection of a registration on the Primary Register"—which the San Diego Comic-Con presently enjoys, thereby justifying their suit for infringement. To be continued.... ■ The trial of Malaysian editoonist Zunar, who faces 43 years in prison if convicted of nine charges of sedition as determined by a British-colonial era law, has been postponed until the court hears and decides a separate case that challenges the constitutionality of the Sedition Act. Zunar, who could travel to another country, says he’ll stick around for his trial, saying: “The job of political cartoonists everywhere in the world is to criticize the government of the day. But in Malaysia, that is not enough. When you live in a repressive regime, you not only criticize, you have to fight. My job is to fight through cartoons.” ■ Bugs Bunny turned 75 on July 27, the date in 1940 that “A Wild Hare,” the first of the wascally wabbit animated cartoons, debuted. Although Bugs didn’t have a name at first, he came to be called “Bugs’ bunny” because one of the Warner Bros animation directors, Joseph Benjamin “Bugs” Hardaway, had directed two previous cartoons in which a prototypical rabbit appeared. When other directors—first Chuck Jones, then (for “A Wild Hare’) Tex Avery—conjured up cartoons with a rabbit in them, they off-handedly referred to “Bugs’ bunny.” But the Bugs in “A Wild Hare” wasn’t much like Bugs’ bunny, and he soon (in over 175 cartoons) evolved into an irrepressible wise-acre who survives every attempt on his peace-and-quiet with his wit and attitude intact. Perhaps for that reason, Bugs is often seen as the ideal American.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “The sun, with all those planets revolving around it and dependent on it, can still ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do.”—Galileo Galilei “Used to be you couldn’t be gay. Now you can be gay, but you can’t smoke. There’s always something.”—Painter David Hockney “Inside every old person is a young prson wondering what happened.”—Terry Pratchett

SANDY EGGO AGAIN The 46th Con Job Dubbing itself

as a popular culture event, the annual San Diego disturbance (this year, July

9-12) doesn’t embrace much of what we’d consider pop culture: emphasizing

movies, tv and gaming, the Con offers little or nothing about music, sports,

youth fashion in clothing, reality tv, social media or any of the rest of the

realm of popular culture. “Lost’s” Carlton Cuse, who’s been a regular star at the Comic-Con since “Lost” debuted several years ago, thinks the Con is more oriented to television now than it once was. “When we were doing ‘Lost,’ we were the first tv show in Hall H [the Con’s largest meeting room]. Now that’s much more commonplace. There’s just so much more television and so much more genre tv. ... In fact, I think a lot of movies don’t come to Comic-Con right now. ...” But Cuse does, and he enjoys it immensely. Growing up with a single, working mother, his hours after school were spent watching tv, he told USA Today’s Bill Keveney. “They would show all these great old Universal genre movies. Those shows and movies were my companions in my youth. Comic-Con, for me, is just a celebration of all the things I thought were weird about me that now have become incredibly mainstream.” Despite its preoccupation with movies and tv and the walking dead, the Con hasn’t strayed as far from its original purposes as we might suppose. At its founding almost half-a-century ago, the Comic-Con focused on sf and movies and tv as well as comics. Although the emphasis has shifted away from Golden Age comic books (which are minimally represented these days—and usually at prices none of their fans can afford), comics are still at the core of the Con. But you wouldn’t know it from reading Entertainment Weekly’s post-Con report in its July 24 issue; herewith, the opening paragraph (in italics)—: When you think about it, San Diego’s Comic-Con International is like one colossal expanded-universe movie in which the heroes of “Star Wars” battle the warriors of “Game of Thrones,” and Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman brawl with Deadpool and the X-Men. Throw in some assorted zombies, maybe a few orcs from “Warcraft,” and send them running onto the battlefields of “The Hunger Games: Mockingly—Part 2,” and you have something truly ... epic.” EW then spends the next dozen-plus pages on photocoverage of “the gorgeous and the geeky”—the star actors of the funnybook superhero movies and related genre: “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” “Fear the Walking Dead,” “Superman v Batman: Dawn of Justice,” “Deadpool,” “Heroes Reborn,” “The Vampire Diaries,” “Extant,” “Orphan Black,” “Supergirl,” “The Frankenstein Code,” “Fantastic Four,” and others of the ilk, including “Scream Queens,” starring the irrepressible Jamie Lee Curtis, who made her first Comic-Con appearance this year, telling the audience: “For six years, I’ve been selling yogurt that makes you shit.” Then comes a 6-page preview of “X-Men: The Apocalypse.” Comic books aren’t mentioned. Nowhere in the 18 pages. You’d think the news-worthy reboot of Archie would rate a paragraph. But, no. Nothing. You could buy a copy of the first issue of the “new” Archie at the Archie Comics Booth—but not for cover price: issues were sealed in plastic so you couldn’t peek inside and offered for some outrageous price—what? $20? $15? Merely $10? Can’t remember. Doesn’t matter: the scam was an unabashed rip-off. I decided to wait until I could get my copy at the neighborhood comic book shop for cover price.

Conan at the Con THE MAGNIFICENTLY COIFFED Conan O’Brien broadcast “live” his late-night show from San Diego, and in addition to his usual brand of silliness, he referenced the Comic-Con frequently. EW quotes him: “There’s a Comic-Con guide that recommends that you bring condoms. I just want to point out–the condom is the only thing at Comic-Con that’s more valuable after you take it out of the package.” The

comment shows that Conan knows that comic books are most valuable when sealed

between air-tight plastic plates. Comic books weren’t mentioned much, if at all. Although superheroes were. The Comic-Con is a hopelessly mashed-together chaotic concatenation of the experience of human amusements in a mob. So the reminder of Rancid Raves coverage is a similar mash-up of experience; herewith—:

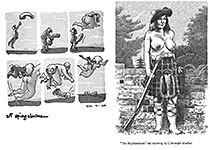

Remembering My First Comic-Con DURING THE CON, I bought Jackie Estrada’s Comic Book People 2: Photographs from the 1990s (156 9x12-inch pages, b/w with color section; 2015 Exhibit A Press hardcover, $34.95)—an excellent book, about which my review of the first volume last time (Op.341) can serve in this one—and it settled a matter about which I’ve lately pondered a little: when did I first attend the San Diego Comici-Con? Among Estrada’s photos in Book 2 are those of girlie cartoonist and Golden Age Blackhawks artist Bill Ward and For Better or For Worse’s Lynn Johnston, both of whom I met during my first Comic-Con. The photos are dated 1991, so the 2015 edition of the extravaganza was my 24th. I may have missed one along the way: can’t say for sure. So let’s just leave it at 24th, which’ll make next year’s my 25th—perhaps a good number to quit at. We’ll see. I was in Artists Alley in my first few encounters with the Con. At my first, the Artists Alley tables were lined up against a far wall. Giving myself a break one afternoon, I wandered down the line and when I saw some Bill Ward originals taped to the wall behind a large dark-haired somewhat-portly man, I assumed that personage was Ward and introduced myself. I was midway through an encomium of appreciation—laced with references to my long-lost hormonal youth—when Sergio Aragones, whom I’d never met (but everyone recognizes him), came dashing up to tell Ward how much he admired his drawings of women. When I introduced myself, Sergio suddenly remarked how much he liked my “little girls.” How he could have known about them then, I dunno. My magazine girlie cartoonist career had been abandoned ten years before, so where was he seeing my stuff? Dunno. And maybe he was just saying something nice. But whatever it was, I’ve treasured it the encounter. Ward’s originals were huge—two by three feet, on tissue paper or something equally fragile; conte crayon generously applied to give the pictures a highly polished look. Ward’s wife was sitting next to him and commented that she’d delivered many of the originals to the publisher, mostly, in Ward’s heyday as a girlie cartoonist, Humorama. Lynn Johnston had given a presentation at the evening meeting of the Southern California Cartoonists Society, and the next day, she came by my table. I can’t remember what, exactly, she said upon beholding an array of my lewd ladies, but it was something along the line of “Good Grief! Lookit the boobs on these babes!” And she wasn’t necessarily being complimentary.

She didn’t see the display at hand, but the girls were anatomically similar. But by the next time we met—months, perhaps years later—she’d forgotten. Or so she claimed. She said she could never remember names, mine included.

Fading Excitement I’VE ATTENDED SLIGHTLY MORE THAN HALF of the Comic-Cons. (Others, of course, have attended more, so half, while a minor distinction, is scarcely anything to brag about or to take fanboy credit for.) But when I speak of ending my annual trek to sunny San Diego, it’s because at this year’s, I felt little of the excitement I have felt during the preceding 23. Dunno why. And I’m not alone. A comic book writer, Van Jensen, also sensed a change in the air this year. Like others, he felt that television was replacing Hollywood movies at the Con. As recently as three years ago, several of the hotels around the Convention Center turned themselves into gigantic billboards, “wrapped” top to bottom with massive advertisements for forthcoming movies. This year, only one hotel had an entire side plastered with an ad for a motion picture (“Stain”? Or “Strain”? and maybe it was for a tv show; I’m not sure). One other hotel had a side-girdling sign, but that sign was for Conan O’Brien’s tv show being staged at the Con. As the movie industry pulled back, television “rushed in to fill the void,” Jensen said. “There were plenty of ads around the city and convention for tv shows, but they were all smaller, less splashy that the massive promotions for movies in years past.” And since marketing budgets for tv are smaller than those for movies, “way less money is being spent” as the Comic-Con becomes tv-centric. “And the party scene has dried up,” Jensen continued his report at grantland.com. The major talent agencies have apparently decided not to host elaborate events because of budgetary concerns and a sense that the Con “wasn’t the ‘it’ place it once was.” “For those of us who actually make and sell comic books for a living,” Jensen went on, “Comic-Con has become less and less of a sure bet. There are a ton of attendees, yes; but those people increasingly come to have a ‘Con experience.’” They’re not comic book fans. They parade around and look. But they don’t buy books. “It’s an expensive show, and sales haven’t risen to match the costs,” Jensen said. Some publishers I talked with admitted that they don’t make money at the Con. One said his company comes because it’s a staff-morale builder—not a sales opportunity. Many now say that the Comic-Con is “too big for its own good,” Jensen said, “—so busy that everyone who isn’t an A-list star gets lost amid the noise.” Jensen sees hope in the possibility that the Con might move to Los Angeles or Las Vegas. “If it moves, perhaps someone will start a new convention in San Diego, one actually focused on comic books. It’ll start out small, sure. But you never know what the future holds.” Actually, that’s already being tried. In 2012, one of the last remaining Comic-Con founders, Mike Towry, launched Comic Fest in the fall, a “friendly, intimate comic-con experience” that attempts to re-create the original San Diego Comic-Con ambiance. Next year, it moves to winter, February 12-15, in the Town and Country Resort and Convention Center in Mission Valley. For details, visit sdcomicfest.org. But the likelihood that Comic-Con International, the present popular culture incarnation of what used to be a comic book event, will move is remote to the point of non-existent. The Con depends upon an army of volunteer workers, thousands, and they all live in the San Diego area. The Con can’t afford to transport them to a new site, and recruiting a new army with anything close the experience needed would be nearly impossible. Another comics writer, Kelly Sue DeConnick, who has been coming to the Con for ten years, has mixed feelings about the evolution she sees all around: “On the one hand, how can you be negative about something that people are so enthusiastic about that they’ll camp out all the night before [just to get into the big movie- and tv-events taking place in the convention center’s biggest hall]? In the Hall H lines, those people are having the time of their lives. They’ll tell those stories to their children.” But she also misses the Con of yesteryear: “It used to be more casual and it used to be a lot more about the books, and now there’s a lot more emphasis on other media and the industry hustle.” Interviewed by James Kim and Henry Chase at scpr.org, DeConnick was asked about women in comics—those who produce the books, and the female characters in the books. And she had a novel explanation for the increase in the number of women in comics: “I think cosplay has been one of the driving forces behind [more women in comics]. There are so many more women participating in not just the comic book fandom but the Con culture as well—at San Diego and other cons—and that allows us to support a wider diversity of books.” Books about women characters and by women writers and artists. “Last year at the New York Comic-Con,” DeConnick finished, “—at just the ‘Women in Marvel’ panel, there were so many women on stage that I literally had no place to sit. I sat on the floor.” The size of the Sandy Eggo extravaganza is beginning to take a toll. At publishersweekly.com, Heidi MacDonald reported: “Many comics professionals are openly concerned that Comic-Con is simply becoming too big for small publishers—indeed many believe the show is already too big. Artist Alley exhibitor Anina Bennett, co-creator of the Boilerplate series of books, told PW that this was their last year as an exhibitor. ‘There are just fewer and fewer people who come to buy the kind of books we’re putting out,’ she said, adding that she has ‘issues with all the big Cons’ but noting that ‘Comic-Con in particular is too big, overwhelming, expensive, and diffuse, spread out.’ She lamented that ‘the big cons have increasingly become ‘general audience’ shows,’ and the fans they attract are not necessarily attending to buy books.” MacDonald also thinks “diversity and rising sales for comics aimed at young readers are trends reflected at both this year’s San Diego Comic-Con and at this year’s Will Eisner Comics Industry Awards. A record number of books by and for women scored wins at this year’s Eisner awards ceremony, perhaps best signified by the two awards that went to Boom! Studios’ bestselling Lumberjanes, which won both Best Publication for Teens and Best New Publication. Indeed, the moment marked a new level of diversity in content as well as creators. Co-creators Shannon Watters, an editor at Boom! and artist Noelle Stevenson literally cried with joy as they accepted the awards.”

But All Is Not Gloom There were numerous happy moments—: Having lunch one day on the terrace with Scott McCloud and his wife Ivy, Scott reporting that his current project involves studying the rhetoric (my word, not his) of visual art. Finding a Shane Glines book, Retro Cartoon, at Stuart Ng’s booth. Talking with Dean Yeagle about the post-Michelle Urry cartoon regime at Playboy. Buying the latest Terry and the Pirates-inspired adventure of Rob Hanes from creator/publisher Randy Reynaldo, who’s been producing this comic book title ever since I met him at one of my earliest Comic-Cons; the latest issue takes us back to Hanes’ origin. Graphic designer/editor Jon Cooke came up to hand me copies of every issue (three) of his magazine, ACE (“All Comics Evaluated”), which he defiantly launched in April as a print vehicle, proclaiming the viability of print and intending to fill a gap that’s existed since the collapse of Wizard—namely, a monthly price guide, but this one, Cooke said with a grin, also a better solid news zine about the contemporary comic book biz plus “old stuff and wonders yet to come.” The first issue and its two sequels are jammed with good articles—news and interviews—and a 50-page price guide. Alas, after three issues, Cooke told me with a shrug, ACE is going digital. Couldn’t make it as print. I attended the Spotlight session for Lalo Alcaraz, creator of the comic strip La Cucaracha, editooonist, consultant on the forthcoming animated tv series “Bordertown” and general all-purpose gadfly. The last time he attended the Con was more than 20 years ago when he sneaked in. He had returned to San Diego after an academic sojourn at Berkeley and was peddling copies of his Pocho magazine. He was just walking around the Con with his friends when a “ticked-off seller—who’d actually paid for his booth—rightly called the authorities, and we were escorted off the premises by security.” This time, as a visiting dignitary, Lalo can be said to have been escorted onto the premises. He began his session by fumbling with electronic hook-ups, muttering to himself, then saying—“Talking to myself. What do you expect? I’m a professional cartoonist.” He used part of his time to promote “Bordertown,” showing clips from the series. Interviewed by Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs.com, Lalo denied that Donald Trump had been hired to do promotions for the new adult animated tv show set on the border between Mexico and the U.S. “‘Bordertown’

is a smart, brash and super-funny and super-diverse project whose ti “The show can have over-the-top satire in it,” he continued, “but it should have some kind of point if possible—good, thoughtful and occasionally very rude satire. It doesn’t get more fulfilling than that to this old Chicano political cartoonist.”

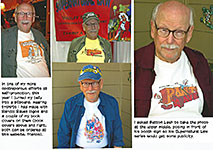

I ALSO WATCHED THE SPOTLIGHT illuminate Craig Yoe, who (“humble little me”) couldn’t take a Spotlight on himself very seriously. He designed the whole session as a send-up of the old “This Is Your Life” tv show, beginning with a video blaring popular marching songs followed by “testimonies” from masked “mystery guests” who removed their masks one-by-one to “reveal dark secrets” about Yoe’s past (which includes being creative director at Nickelodeon, Disney and the Muppets, “where I had the privilege of working closely with Jim Henson”; working with everybody from Stan Lee, Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby to Britney Spears, Usher and Michael Jackson; producing books of comics history and historical reprints; being the senior designer at Marvin Glass and Associates, the first and world’s largest toy think tank, and getting six toy patents in his name). Spotlight sessions will doubtless never recover their dignity after this mockery. But there was a serious moment: Yoe received the coveted Inkpot Award at this session. I

spent two hours a day hanging out at the booth of the National Cartoonists

Society, selling my new book, talking with Luann’s Greg Evans and

his Luann inspiration daughter, Karen, who now helps write the strip,

and meeting and talking with Jason Chatfield, who produces Ginger Megs, Australia’s iconic comic strip. 9 Chickweed Lane’s Brooke McEldowney was making sketches of the passing scene that he posted at his Pibgorn website. Lalo Alcaraz had included the Comic-Con in his strip, La Cucaracha during

the week. Even the staid New Yorker took notice of the Con. I made a presentation during the Comic Arts Conference, the scholarly clubhouse held every year in the most remote meeting room at the Convention Center. I talked about Wally Wallgren, the long forgotten soldier cartoonist of World War I. It’s a chapter in my new book, Insider Histories of Cartooning; and you can read the whole Wally thing at this site—at Harv’s Hindsight for February 2009. I had ticked several presentations that looked intriguing enough to attend, but after a couple of them proved— again, if it needed proof— that my hearing aids aren’t up to capturing much of what was being said, I gave up and wandered the exhibit hall. For hour after hour after hour. But I missed some of the ambiance of yore. I found no action-figures of scantily attired bimbos to buy. Original art is no longer within my price range. Ditto old funnybooks. On the plus side, I had no run-ins with the Security Gestapo, eager to prevent me from blocking firelanes or going the wrong way down one-way hallways. I was probably going the right way down the one-ways; works every time to forestall confrontations with the Gestapo but not my usual style. Old guys tend to be cranky and one-way themselves. There seemed this year fewer cosplayers. In previous years, it took no effort at all to see 4-5 Captain Americas and as many Wonder Womans. But this year, not so many, it seemed to me. Maybe the Walking Dead costumes contributed to my impression: people wearing tattered clothing seemed ordinary not costumed. Still, there weren’t many of those either. Here, just at the elbow of your eye, are some photos I took at the Con, scarcely complete “coverage” in the journalistic sense, but a sampling of a few key factoids.

Sandy Eggo Will Stay in San Diego through 2018 LAST SPRING, there were rumors that the Comic-Con, whose contract with the city runs out after next year, was considering other sites—Los Angeles, Las Vegas, even (maybe) Anaheim. Although a genuine effort to consider other sites would act as leverage to lower costs in San Diego if properly applied, no one really wants the Comic-Con to leave San Diego. The city—hotels and all other retail businesses—makes millions on the big Con; and the Con staff, mostly volunteers who live in the San Diego vicinity, don’t want to leave either, and they’d be hard (if not impossible) to replace at another venue. So it is perhaps a foregone conclusion that the Comic-Con signed up for a two-year extension in San Diego, taking the convention to 2018. Next year, the dates are July 21-24, a happier distance from July Fourth. The city arranged with the convention center some healthier discounts on facilities fees for the next Comic-Cons, but hotel room rates remain shockingly high. The over-all average convention (i.e., discounted) rate is $237/night, which doesn’t seem bad. Plus taxes, it’s probably $250/night. Still not bad. But the average includes 13 hotels in distant Mission Valley, where the average convention rate is only $192, bringing down the city’s over-all average. Downtown hotels average a whopping $266 plus taxes. For a room in a downtown hotel, you’re looking at $290/night (including taxes) on the average; and with 15 downtown hotels charging more than $300/night, you can easily be spending $300-350 a night for a bed and a bathroom. That’s a lot. I say “shockingly high” because the Comic-Con management should have been able to negotiate much higher discounts—i.e., lower rates. The hotel I stayed at was $300/night plus taxes (came to $330/night). But if I’d been staying there the week before or the week after, the rate would have been $50-60/night lower. And that’s just the regular, walk-in-off-the-street rate, not discounted. Heidi MacDonald at comicsbeat.com checked around for other room rates, too, and she found that a hotel charging a Comic-Con rate of $299/night charged only $159/night later in the summer. She nonetheless concluded that $300/night for a summer weekend in San Diego was “within the market range.” Tourist trade on summer weekends keeps the room rates high. Maybe so. But a good negotiator could have persuaded the hotels to do better. In one of my other lives, I spent almost 30 years as a convention manager, and I negotiated room rates in cities all across the country. The customer always has a lever if he/she knows how to use it. Without conducting a seminar on the subject, here’s how it might have worked in San Diego—: If you ask the hotels for big discounts, they point to their weekend tourist traffic that yields a healthy $300/night revenue. Then they say they don’t really need the Comic-Con business because of that big $300/night revenue. But the Comic-Con’s leverage is that it is more than weekend occupancy. Tourists might stay two nights, typically Friday and Saturday. But Comic-Con attendees (including a few thousand exhibitors) stay for four or five nights. Two nights at $300 each produces $600 revenue for the hotel. Hotels could get the same revenue with $150/night rates for four nights. More than that (say, $175/night) would be a bonanza. Why would a hotel want its rates that low? Because every night is followed by breakfast the next morning, and most of those breaking their fast will do so in the hotel’s restaurant; that means even more revenue for the hotel. And the Comic-Con would fill the hotel’s rooms. High occupancy and breakfasts galore. A hotel waiting around for weekend tourists will be partially empty for the rest of the week. And the cheery picture I’ve just painted in favor of Comic-Con occupancy doesn’t even consider revenue from the hotel bars. All that revenue is why the Comic-Con is good business for San Diego hotels. But the Con management, beginning as novices and apparently not learning much over the years, believes the hotels when they point to tourist occupancy as competition for Comic-Con attendees, not seeing that tourists aren’t worth as much to the hotels as Comic-Con attendees. The San Diego hotels have been bludgeoned by the city into keeping the 2015 room rates for the next three years. That’s good. Better than no cap at all. We’ve seen how the hotels are raping Comic-Con attendees; at least for the next three years (as I read reports of the agreement), the rape will be a little less brutal. But if the Comic-Con management had been a little more knowlegeable, the rates would have been kept lower for years before this. Unhappily, it’s probably too late to re-visit the issue—for next year or for the next three years. After that? Well, they’re probably in too deep to maneuver much—unless they opt to seriously consider alternative sites and wield that weapon effectively over the San Diego convention community. Judging from past performance, that’s not likely.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

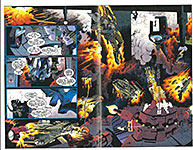

EAGER, NO DOUBT—if not absolutely anxious—to match its chief competitor with an all-title spanning series, Marvel has launched Secret War. However well-intentioned, it is, alas, is just another brand of bust, recycling tired old concepts yet another time. Like DC’s Convergence only different. The opening page in each of the two first issues I’ve encountered— 1872 and Korvac Saga— thunders with ominous import: “The Multiverse was destroyed! The heroes of Earth-616 and Earth 1610 were powerless to save it! Now, all that remains ... is Battleworld! A massive, patchwork planet composed of the fragments of worlds that no longer exist, maintained by the iron will of its god and master, Victor von Doom! Each region is a domain unto itself!” The prose is so inflamed it scorches the eyeballs and pierces them with exclamation points!! In 1872, however, we encounter no such blasted world, no patchwork planet. Instead, we have an old fashioned Western set in a town menaced by a gang of thugs and a land-grabbing, water-hogging plutocrat. The plutocrat’s name is Fisk; yup, the Kingpin. The town—called, a sly in-joke, Timely (for those who’ve just joined us, that’s one of the publisher’s early names)—is protected by a stalwart sheriff, Steve Rogers, whose deputy, Barnes, has been recently slain. Rogers is sometimes assisted by the town drunk, Stark. And the story is narrated by a newspaper publisher/editor/reporter, Ben Urich. The whole concept is an in-house nostalgia trip for fanboys (chiefly those writing the book).

The whole concept is an in-house nostalgia trip for fanboys. In this issue’s complete episode, Sheriff Rogers rescues a local Native American from a necktie party, proclaiming, triumphantly, “Whatever this man is accused of, he’ll go before a judge.” This hackneyed episode establishes Rogers as a principled champion, alone against a hostile population—the formula of the Western of yore and song. A few pages later, the hanging gang of thugs comes vengefully looking for Rogers, and he manages, with Stark’s assistance, to kill or disable them all in a series of actions so violent that Rogers, overcome with revulsion, vomits. (Surely, an unprecedented event in superhero comics.) The issue ends on a double-barreled cliff-hanger: Fisk gets a mysterious note from a cohort, the governor Roxxon, and Urich, a groveling coward, regrets his cowardice but justifies it, murmuring: “You wanted to bring change to Timely, but instead, you summoned death.” This pronouncement is followed by a full-page depicting the arrival in Timely of a dude in black, carrying an Ace of spades and displaying a small target on his forehead—accompanied by the Old West version of Dorothy, the Tin-man and the cowardly Lion. Or so it seems. Gerry Duggan’s story holds together nicely, and he and artist Nik Virella know their way around the storytelling capacities of the medium. Virella’s style is wholly competent and familiar with lines both bold and fine, deftly shadowed when needed. The connection to the Battleworld of the book’s prologue is mercifully non-existent. But at least the concept of the town of Timely populated by Marvel heroes in boots and badges has the ring of novelty about it. We can’t say the same for Korvac Saga. In fact, the opening page conjures a mighty yawn. It lists the names of that almost entirely new band of superheroes—Starhawk, Major Victory, Charlie-27, Martinex, Nicholette Gold, Geena Drake, and (wow! a full-blown bafflement) Yondu Udonta (?). And the current issue of Marvel Previews adds even more fraught and meaningless but ringing names—the Runaways, Ghost Racers, Night Nurse, the Soska Sisters and (most fearsome of all) Mill-E: the Model Citizen, “Doom’s PR and Outreach robot extraordinaire.” Marvel’s durable Millie the Model, dontcha know. Dan Abnett’s story is a simple construct—the world is theatened by a dire entity that has taken the stars from the skies, and the Guardians (all those names from Starhawk to Udonta) must protect the citizenry. Which they do in the issue’s complete episode, wherein a street derelict named Emil Blonsky “escalates” into a towering monster (whom the Guardians laughably address throughout the ensuing fight as “Mr. Blonsky”) that Yondu Udonta kills with an arrow to the eye, apologizing afterward to Major Victory: “An eye seemed the only vulnerable point, Major, I ...” Mostly, the significance of this encounter is lost in the parade of superheroes, talking among themselves as a way of introducing us and establishing their names. After the battle, the book shifts to a domestic scene between the ruling Lord Michael Korvac and his loving wife, Carina, discussing the threat posed by a rival, Baron Simon Williams, and then we have Geena Drake and Starhawk discussing the threat posed by a mental contamination loose in the city. “We must locate the source of this infection and cure it,” says Starhawk. If they don’t, “then Michael Korva will seem unable to keep his domain in order. He will have failed to maintain Doomlaw. Then Thor Corps will be sent in to purge us.” Doomlaw? Thor Corps? As if all these new notions haven’t been enough to overwhelm us with ennui, Abnett next introduces the Avengers, and they and the Guardians introduce themselves to each other with fake friendly banter, shaking hands all around, after which an assembly of citizens is addressed by Korvac and Williams, rivals whose mutual animosity is palpable. Then Lady Carina goes to her room, looks out at the night, and wonders where the stars have gone. End of issue. Otto

Schmidt’s drawings ripple with muscularity, no feathering and not much

shadowing, definition achieved with tiny lines that etch muscles and folds.

It’s a pleasure to watch him, but his drawings are not enough to get me to return

for another dose of Abnett’s conglomeration of too many heroes and too many new

named but unspecified menaces. It’s nearly impossible to focus on which menace

matters most, and so the whole miasma evaporates in a flare of colorful

costumes. At least in this title, the unwinding of the alleged story alludes, albeit vaguely, to a larger disaster, maybe the aforementioned Battleworld and patchwork planet and so on. But how this is a secret war evades me. What’s secret about it? Besides, it’s all just another Marvelution. More threadbare, worn-out gimmicks whirling by again. We’ve seen it all before. Bickering personalities all over the place. Superheroes one more time saving the world from obliteration. Marvel is scarcely alone in exposing, time after time, the poverty of its imagination when it comes to superheroes. As we’ve seen with DC’s Convergence titles, the superhero concept has worn thin there, too. The downfall began years ago whenever it was decided, in deference to a largely imaginary tut-tutting parental population, that superheroes couldn’t actually kill any of the fiends they fought. Killing would be messy and not very nice. So superheroes were equipped with magical “force field” powers that shot from their fingertips and interplanetary villains as superpowered as the heroes. No one was ever killed or disfigured: they were simply knocked over for a few pages. These bloodless battles limited storytelling possibilities severely. But the cast of superheroes was there, on call, so something had to happen. And the range of somethings was very constricted. Eventually, it all went to the big silver screen and culminated in a series of explosions, each bigger and more colorful than the last. But once you’ve seen one explosion fill the screen, you’ve seen them all. Boredom sets in. And it’s set in here at Rancid Raves. We’re no longer amused. Meanwhile, at DC Comics, another series is a-borning. Something called “Truth”? Or is it “Robin Wars”? Here we go again.

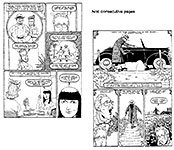

THE BEST THING about the first issue of Will Eisner’s The Spirit from Dynamite Entertainment is Eric Powell’s cover (one of thirteen variants, each by another artist). In fact, Powell’s cover is the only thing even vaguely reminiscent of Eisner’s creation. Matt Wagner, who was widely touted as “the only person who could continue the Spirit,” has produced a resounding flop of a story. And Dan Schkade’s pictures are a joke, a bad joke. The story’s opening splash page is a faux newspaper page with a long story speculating about the present fate of the Spirit, who hasn’t been seen for two years. Commissioner Dolan, we are told, is about to retire, and the unofficial status of the Spirit in the police department is debated. Lots of text; tiny pictures. Next comes a segment in which a reporter interviews Dolan about the Spirit; then, three pages reviewing the origin of the Spirit. Then Dolan’s daughter, Ellen, drops by; long the paramour of the Spirit, she’s now accompanied by a new beau, an unabashedly hen-pecked errand boy named Archie. The story then shifts ground altogether, and we find ourselves in the office of Strunk and White, private detectives. That’s Sammy Strunk and Ebony White, the former a stand-in sidekick of the Spirit’s when Eisner finally reacted to the criticism that Ebony, the Spirit’s longtime black accomplice, was a racist caricature; he retired Ebony and gave the Spirit a white kid cohort, Sammy. Now the two youths are together as partners in a detective agency. Their last names, Wagner slyly reminds us (those of us with a writing course in our background), are the same as the authors of the celebrated Elements of Style, a handbook about grammatical and syntactical niceties (once called by Time one of the most influential books written in English). The opening sequence has Sammy trying to solve a grammar problem for a “client” who’s phoned in, asking about dangling participles. How Wagner was persuaded that most comic book readers would get this underhanded comedy defies explanation. The ensuing 11 pages—exactly half of this issue—are devoted to Sammy and Ebony extracting from a minor difficulty the son of a friend. It’s the only complete episode in the book. Half the issue. Focuses on two minor characters in the Spirit cast. And two of those pages introduce a towering assistant for Sammy and Ebony—one Francis, “the Boulder.” A wholly unnecessary creation. Oh, and we find out Ebony’s given first name is Aloysius. The episode has a few intimations of Eisner’s comedic flare, but not enough. And it’s too long for whatever little it contributes. A misfire if ever there was one. At the end, the two junior detectives resolve to use their dubious detective skills to find the missing Spirit, who has been missing, need I say—except in flashback, er, flashes—for the entire first issue of this come-back title . If this comic book survives at all, it will do so based entirely upon the reputation of the Spirit’s creator, the late great Will Eisner. Nothing in this Wagner-Schkade issue in and of itself is sufficiently provocative to assemble a loyal—or even a vaguely interested—readership. Not only has Wagner failed to evoke much of anything remotely resembling an Eisner ambiance, but Schkade’s pictures are such lame would-be imitations that I cringed, page after page. I don’t expect that revivals of the Spirit should be drawn by wannabe Eisners, seeking to imitate the master. But I do expect competence. And Schkade falls spectacularly short of that. His panel compositions are empty and unimaginative; his anatomy, stiff and wooden. He is most comfortable drawing with an unembellished line—no feathering, no shadowing (hallmarks of Eisner’s style). And when he attempts Eisner-ish chiaroscuro, he simply drops in solid blacks in geometric shapes that serve no dramatic purpose whatsoever.

This comic book is a disaster, and it saddens me to see how mutilated Eisner’s signal achievement has become at the hands of these two rank amateurs. Dynamite Entertainment should be ashamed of itself.

EVEN IF A

REVIVAL OF THE SPIRIT isn’t drawn in Eisner’s style—and, as I said, I don’t

demand that much devotion— it ought, at least, to evoke the dim-lighted atmosphere

of the Spirit stories. Danijel Zezelj’s treatment of Brian Wood’s story

in Starve is extremely shadowed by Eisner standards, but it’s in the

right stylistic realm. In one of the complete episodes in the book, Cruikshank makes himself a bloody mary over the objections of the stewardess on the airplane taking him back to New York and the cooking show he left behind. It shows Cruikshank to be a self-centered do-it-yourself bully—albeit not without reason. A cooking show and its chef. All the ingredients of a boring comic book. Two things rescue it. First, there’s a sociological element—the rich getting richer at the expense of the poor, whom the rich keep amused with television shows like Cruikshank’s “Starved; and Zezelj’s spectacularly styled drawings. Boldly lined and deeply shadowed, they bespeak a bleak and unforgiving world—Cruikshank’s world. And akin to the Spirit’s world.

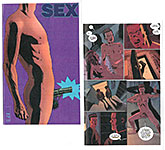

THE COVER of

the 14th issue of Sex is—no contest—the most flagrant

representation of what comic books are all about than has ever been, er,

concocted. (You should pardon the expression.) For the first half-dozen or so issues, the book lived up to its title by exploring human sexual activity in as many of its forms as can be readily imagined. For a while, it seemed that each issue would be dedicated to depicting one kind of sex after another—first the usual missionary position, then in the next issue, rear entry; then fallatitio, then cunnilingus and so on, through the entire Karma Sutra instructional manual. But once writer Joe Casey and artist Piotr Kowalski reached the sixth or seventh issue, they’d apparently exhausted their imaginations (betraying the dismal poverty of same), and the story descended into ordinary thuggery and malevolence. And talk, lots of talk. As the characters talked, menace mounted on all sides, and the criminal element in Saturn City verged upon taking over the city. And the comic book. The hero of this tale is Simon Cooke, a plutocrat playboy who was once a costumed crime fighter named the Armored Saint. When he was costumed, he often ran into the Shadow Lynx, a shapely costumed thief whose other identity is Annabelle Lagravenese. That was before Sex began. When Casey and Kowalski launched the title, Cooke has given up adventuring and Annabelle is running a high-priced brothel. Writing under another rubric, Casey has said that what fascinated him about superheroes was how repressed they were sexually. Ostensibly, Sex, then, is about that repression. Despite the frequent depiction of all sorts of sexual positions—and, even, the erect male member occasionally—Cooke and Annabelle have yet to get it on. They obviously want to. And much of the narrative tension in the title arises from the intensity of their inclination. It isn’t until No.20 that the two have a face-to-face that promises to lead to one variety of congressional activity or another. Alas, that doesn’t work out. But Annabelle does take most of her clothes off, and there’s a flashback during which we see, for the first time (twenty issues in), the Shadow Lynx and, vaguely in the dim and dark recesses, the Armored Saint. Clearly, Casey is toying with us. While displaying all sorts of sexual activity issue after issue, he is denying us the one thing his story seems to promise—a romantic sexual relationship between the ostensible hero and heroine, a vivid unhorsing of the superheroic repression of which he speaks. But, no. Instead, he’s showing us sex while at the same time making us repress our desire. Well, maybe we’re not actually repressing, but Casey’s narrative seems symbolically engineered to frustrate us in much the same way that repression would. Cute.

THE FINAL ISSUE, the fourth, of The Big Con Job came out a couple weeks before the San Diego Comic-Con, the presumed site of the crime. Alas, the resolution of the 4-issue tale, like many of the stories produced by Jimmy Palmiotti, was an anemic disappointment. Palmiotti can concoct fascinating situations with fraught predicaments, but he cannot, seemingly, bring them to a conclusion that the concept deserves. This is another instance. In case you’ve forgotten, the story involves a gaggle of one-time motion picture or tv stars, whose fame has evaporated with age and who are forced to make a meager living by signing autographs at comic-cons around the country. This bunch is recruited by an operator named Tony to stage a heist at the San Diego Comic-Con, where, as guests, they’ll be able to move through various facets of the scheme unsuspected and undeterred. We spend three issues getting acquainted with the old timers’ miserable lives and anticipating the big change that will happen when they successfully rob the Comic-Con. The heist takes place, at last, in the fourth and last issue of the series. And it’s a let-down. To begin with, the major event—the heist—is related to us by voice-over with aspects of the action depicted, but not as continuous action, which would be a more dramatic and engaging way of telling the tale. After the robbery, the old timers all show up at Tony’s hotel room, where he hands them each an envelope, ostensibly containing a $10,000 deposit on their share of the ill-gotten goods—which will be divvied up later. According to plan, the old timers board an airplane bound for South America, where they’re supposed to meet up with Tony for the sharing of the spoils. But, no—they’ve been had: they see Tony and his paramour boarding another aircraft, signaling that he’s absconding with the loot for himself. At that moment, the police show up and arrest Tony; the old timers, however, stay on their plane and make a getaway. Later, when they land, they discover that the envelopes Tony gave them are filled with newspaper clippings, not money. They’ve been played. But a sympathetic FBI agent arranges for them to be let off the legal hook: they’re “victims,” she says, not criminals. So they “escape,” scot free, experiencing no consequences for their illegal enterprise, robbing of the Comic-Con, which they willingly participated in. In that they were scarcely “victims.” So much for moral import. There’s a nice touch: when the old timers get off the plane in South America, they’re met by adoring multitudes, their old movies having created a whole new generation of fans south of the equator. And all the old timers find employment, advising on re-makes of the original movies. That’s a nice genteel ending, everybody more-or-less “happy.” But it’s disappointing: it falls far shy of the sort of thing that could have happened had Palmiotti delivered a conclusion suitable to the diabolical machinations of the setup. I can think of an ending more fitting. In my version (so to speak), Tony gets caught by the police, holding the big bag of money. But that’s not all the money: the old timers each have their $10,000 “advance.” They see Tony getting caught and they have an attack of conscience, so they come forward, report to the police station, and confess—handing over the envelopes with their advances in them. And when the cops open the envelopes, they discover—as do the old timers, watching the envelopes being opened—nothing but newspaper clippings. It suddenly dawns on everyone (us included): all of us realize that the old timers have been conned. That’s where it would end. We never find out what happens next. We know the old timers have been caught, but we also see them regret their crime and confess—doing the right thing at last. They are shamed as naive oldsters, but we don’t know what punishment they’ll have to endure. That, it seems to me, is an ending more fitting the crime than the “happy ever aftering” that Palmiotti gives us.