|

||||||||

Opus 325 (June 5, 2014). Down the rabbit hole this time, we begin with the catastrophic news about the comics section at the New York Post, then go on with our annual Reuben Report on the NCS award winners, including a long appreciation of the innovative career of Reuben winner Wiley Miller, a similarly lengthy fond obit for Morris Weiss—all liberally littered with shreds and patches of NCS history and sundry other cartooning lore (Was William Randolph Hearst really a generous tyrant? Who drew the Golden Age G.I. Joe? How did the Milt Gross Fund get its name?), a rare glimpse of Harv’s Navy cartoon character Cumshaw, and more taboos being broken daily on the comics pages of the nation’s newspapers. And more—much more. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US New York Post Drops Comics Section (And No One Notices) NCS Prez Tom Richmond Protests (And No One Notices) Eastman and Laird Disappeared from Ninja Turtles Jessica Alba in Frank Miller’s Latest Sin City Flick

AWARD SEASON: Part Three The NCS Reubens Summary of Program Division Award Winners (and Nominees) Listed Origin of the Reuben Trophy Wiley Miller Wins Rueben Harvey and Cumshaw on the Midway Grant Geissman Corrects Report on Feldstein Book

NON SEQUITUR BREAKS NEW GROUND Wiley Miller’s Professional Biography

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Stephan Pastis and Darby Conley Bloop Taboos Being Broken Some More

COLLECTOR’S CORNICHE Pre-Plastic Jack Cole Cartoon Who Drew Golden Age G.I. Joe

FINAL FLING PORTFOLIO Two 1978-82 Cartoons by Harvey

PASSIN’ THROUGH Morris Weiss, 1915-2014 Weiss on Hearst’s Generosity

NCS’s MILT GROSS FUND The Mystery Explained

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary (and therefore tedious) reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits THE NEW YORK POST has done the unspeakable. The impossible. The wholly unforeseen. It dropped its comics section on May 6, thereby jumping the shark for one of the most enduring and endearing features of the daily newspaper. From the beginning, the comics thrived in American newspapers because they increased circulation. They sold newspapers. And they have continued even into the fraught 21st century to be a bellwether for the bean counters’ bottom line. Readership surveys have consistently found that the comics always—regardless of age group or demographic—rank no lower than third in popularity. After the front page and, sometimes, after the sports section. With that kind of record, no one has ever anticipated that some newspaper somewhere would discontinue its entire comics section. But the Post did. At a time when newspaper readership is declining, a major metropolitan newspaper has deliberately discarded a feature that has proven itself popular with readers. Stupid. But then, newspapers have not recently been covering themselves with glory in the logic department. This insidious and careless move raised two questions immediately. The first—why? The comics section was axed without advance notice or explanation. The Post did nothing to alert its readers to the impending change. “Not even a ransom note, apparently,” said Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs. Media-watchdog blogger Jim Romenesko first took notice of the development two days after it happened, announcing in a headline: “The New York Post Drops Its Comics Section (And Few People Notice).” “Few people notice”? If true—and I’ve seen nothing to contradict this statement—the development bodes ill for newspaper comics everywhere, bringing us to the second pressing question: will other newspapers follow suit? The Post’s comic section was minuscule: only seven strips—Garfield, Wizard of Id, Rhymes with Orange, Mallard Fillmore, Heart of the City, Non Sequitur, and Dennis the Menace. So skimpy that maybe nobody noticed when it disappeared? So if no one noticed, that may be an indication of how reader loyalty lapses drastically during periods of privation. One hopes. But no further news on the matter has blurted out. Yet. And maybe—heaven forfend—no further news is forthcoming, at all. Ever. One blogger opined about why it took two days for comics watchers to notice what the Post had done: “There are many reasons why this story took so long to catch the attention of the comics media. All of those reasons stem from the fact that ‘comics media’ has also abandoned the newspaper strip, by and large. We don’t advocate for the comic strip format, we don’t push for stronger placement in the newspaper platform, we haven’t pushed for better visibility on news organizations’ online platforms, we have never, EVER pushed for the simple and corrective and *obvious* change of simply getting comic strips printed at a reasonable size.” Sounds too true. Was the decision to drop the comics made to save money? Romenesko and others, including Brendan Burford, King Features comics editor, have phoned and e-mailed the Post asking the question. As of May 8, no response. As of June 1, still response. The silence is deafening. How much money could be saved by dropping the comics? The low-end fee for a newspaper strip is, let’s say, $15/week for dailies; another $15 for the Sunday. So the Post might save $210-350 a week by dropping the comics. Not much? But translated into an annual budget, that could be $11,000-18,000 a year. Still not much. Not even enough to hire a freshman reporter. But other metropolitan daily newspapers have 3-4 times the roster of comics. Now we’re talking real money: $33,000-73,000/year. Enough, in some communities, to pay another staff member. (And my estimates are probably low.) Newspaper editors, who are fanatic about news, have always vaguely resented the space they must give up to such frivolous enterprises as the comics. And television program listings. If the Post gets away with dropping its comics, escapes unscathed—and perhaps reader protest, although not yet in evidence, may result in the decision being reversed—other papers are sure to do the same. Soon, no more newspaper comics anywhere. No wonder the president of the National Cartoonists Society, Tom Richmond, dropped everything to write a letter, to wit—:

Dear New York Post— It is with great disappointment, and no small amount of confusion, that I learned of the New York Post’s recent decision to entirely drop the comics page from its publication. Being that the National Cartoonists Society is an organization of professional cartoonists, among whose members are the creators of the majority of the comics that used to grace your comics page, the reason for the disappointment is obvious. The confusion is another matter. We all know the role of newspapers and print media in this electronically interconnected world has changed. They used to be the prominent source of breaking news and opinion on that news in this country. That is no longer the case thanks to the 24/7 nature of the Internet and the continued evolving of how the public consumes its media and entertainment. Today breaking news is old news by the time the newspaper hits the doorstep or the corner newsstand. Handheld devices have untethered the internet from our desktop computers and allowed us to take it along on the bus, the train, into the coffee shop, or wherever we wish to read about what’s going on in the world. Daily newspapers especially have a lot of stiff competition for reader’s eyes these days. That’s where the confusion sets in concerning your decision to drop the comics page. The one strength newspapers and other print publications still have is that they can collect and present perhaps less timely but still relevant expanded news, opinion, and entertainment, written by vetted professionals into a convenient publication of great interest to a local market. Focusing on entertainment and more than a 140 character story on topics that readers still care about seems to me to be the best hope for the continued survival of newspapers. The daily comics are one of the most popular and read sections of newspapers, yet they have been treated like an afterthought for a long time. Despite being a truly American art form with a long and rich tradition and a tremendous following, newspapers have been shrinking the comics to postage-stamp size for years now, and have been reluctant or completely against adding in new, fresh cartoons that might have interest and relevance to younger readers. Now, we have a major newspaper dropping the comics entirely—perhaps one of the few sections that is read by virtually everyone who opens the paper. That seems to be cutting off your nose to spite your face. It’s like a restaurant dropping one of its most popular items, one that keeps people coming back to their establishment, because it costs a bit more to make than the rest of the menu. No one disputes that newspapers are struggling in the face of rising costs and declining readership. However, I don’t believe it is a smart business move to eliminate, in the name of cutting costs, one of the most popular and read parts of a newspaper. I hope you reconsider your decision and reinstate the comics page. It is one of the sections readers enjoy the most, and isn’t providing things your readers want to read the first priority of any publication? Sincerely, Tom Richmond President National Cartoonists Society

He’s right, of course. But we need more than the voice of sweet reason in such a crisis. Where are the bomb-throwers when we need them?

ELSEWHERE In the summer

“double issue” of Entertainment Weekly, an article about the new Teenage

Mutant Ninja Turtles movie (and, incidentally, Andrew Farago’s book, Teenage

Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Ultimate Visual History, hitting the bookstores

June 24) publishes pictures of the turtles showing how through their 30-year

history they evolved visually, as you can see at the elbow of your eye. This

is the issue of the magazine with a cover featuring the bikini-clad Jessica

Alba, touting the August debut of “Frank Miller’s Sin City: A Dame

to

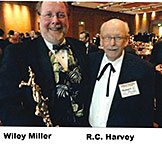

AWARD SEASON: Part Three The NCS Reubens THE BIG

TAKE-AWAY from the Memorial Day weekend meeting of the National Cartoonists

Society is that Non Sequitur’s Wiley Miller was named Cartoonist

of the Year and presented with the Reuben, a heavy metal statuette in the shape

of a pile of comical characters. Three other cartoonists were finalists for the award. All four finalists, as is predictable with the Society, are syndicated newspaper cartoonists. It’s as if cartooning does not exist in other venues than newspapers—despite NCS’s awarding of plaques for achievement in those other venues. The nominees for the Reuben in addition to Miller: Hilary Price, Rhymes With Orange; Stephan Pastis, Pearls Before Swine; and Mark Tatulli, Lio and Heart of the City. Price and Tatulli were first-time finalists; Pastis has now been the bridesmaid for six consecutive times. He should not, however, be discouraged: Dan Piraro (Bizarro) won in 2009 on his eighth nomination; ditto, Pat Brady (Rose Is Rose) in 2004. And we all lost count of the number of times Garry Trudeau was nominated for Doonesbury before he won in 1995. The 2014 NCS “Reubens Weekend,” as it is termed, took place in the Omni Hotel in San Diego, in the shadow of the city’s Convention Center where, in another 6-7 weeks, comics will reign supreme during the International Comic-Con, July 24-27. Over 330 people attended, 160 members plus their spouses and hangers-on. That’s about 40% of the Society’s 495 members, a more than healthy turnout for a volunteer membership organization. It was the 68th annual gathering for patting themselves on the back; and if the New York Post is any predictor of the future, the 68th may be among the last of these happy occasions. As for the self-congratulatory aspect of the event, Dave Coverly had an appropriate rejoinder, made when he accepted the plaque for Best Newspaper Panel: “To a certain extent, we’re slapping ourselves on the back, but,” he added, “—that’s who you want to slap your back.” To be recognized by one’s peers is very satisfying. Originally, the annual NCS event was a solitary awards banquet on a Saturday night in the spring, but through the years, the Reubens Banquet has attracted a weekend’s worth of barnacles—seminars and cocktail hours too numerous to mention—which expanded the dinner to a festival of cartooning that begins on Friday and ends Sunday evening. Friday’s seminars featured: Eddie Pittman, an animation designer and storyboarder by day and an animator by night, who explained that he spends his free time in the wee hours of the morning creating an online graphic novel, Red’s Planet, because he wants complete control over this work (and doesn’t aspire to be a simple cog in the usual animation assemblyline); Eddie Houghton, who, after winning NCS’s Jay Kennedy Memorial Scholarship five years ago, has leaped into animation and comics with all feet forward, producing comic book and storyboards galore; Greg Evans of Luann fame, who displayed a hilarious array of gaffes and blunders he’s made in the 29 years of his strip’s run; and Suzy Spafford, creator of “Suzy’s Zoo,” who explained the operation and philosophy of her greeting card company. The day finished with a cocktail “welcoming party” by the hotel poolside, which, after a couple hours, adjourned to a meeting room where various delusional NCS members performed karaoke in the conviction that they could sing. Almost true: they were loud. Saturday began with the NCS business meeting, a secret conclave. Then came the afternoon’s seminars, featuring presentations by: Jennifer George and Charles Kochman about the new Abrams tome, The Art of Rube Goldberg (reviewed here in Opus 322), accompanied by assorted insights into the man himself from his granddaughter, Jennifer; Sandra Bell-Lundy, who celebrated 20 years of her strip, Between Friends, by tracing its evolution and discussing how she began occasionally to treat of controversial topics in a strip aimed chiefly at women (spousal abuse, fertility treatments); Bunny Hoest Carpenter and John Reiner, mostly the former, who explained how she inherited her husband Bill Hoest’s comics features when he died and how she’s maintained and sustained them, then Reiner, who draws all these features, showed pictures of some of his caricatures, his career apart from The Lockhorns panel cartoon and other Hoest features; then Russ Heath was guided by Mark Evanier into comments about various aspects of his long career in comic books. My impressions of a few of these fugitives appear near here—as does an array of some of the NCS Executive Board.

Then another cocktail “reception” descended upon the multitudes, who, after imbibing a little, went into the ballroom for the Reubens Banquet.

The Reubens Banquet BY TRADITION AND DECREE, the Banquet is a “black-tie” affair, and tuxes and formal gowns abound. The original intention of the formal dress fiat, proclaimed in the mid-1950s, was to infuse dignity into the occasion—to demonstrate, for any who might be interested, that cartoonists were not slovenly unshaven attic-dwellers in tattered t-shirts but normal human beings who cleaned up pretty well. In short, the Banquet as it evolved was viewed as a showcase for the profession: cartoonists were on display. This justification for impersonating penguins disappeared several years ago: since neither the public nor the press is welcome at the Banquet, the display of cartooner dignity no longer serves any purpose. The only people to witness cartoonists in tuxedoed regalia are other cartoonists, who, as a breed, recognize fraud when they see it. Tom Gammill returned for his fourth appearance as emcee, doing his now-familiar impersonation of a clueless wannabe cartoonist. He began with a song-and-dance routine accompanied by a couple of leggy chorines (one of the song’s rhymes was “until R.C. Harvey croaks,” continuing the now-familiar jab-Harvey schtick). Apart from offering occasional witty remarks and introducing the people who presented the awards, Gammill also subjected the audience to a videotape of his clueless idiocy (which ran a little long, alas). The announcement of this year’s Reuben winner is the climactic event of the evening: it is preceded by the presentation of other awards, including the Division Awards in 15 areas of cartooning endeavor. Before those were presented, NCS conferred the Silver T-Square for service to the profession on Bunny Hoest, who is highly regarded among cartoonists for her conviviality and support of the profession and for hosting cocktail parties and other cartooner gatherings at a mansion in the New York suburbs that was built as the realization of her husband’s fondest dream. Next, the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award was presented to Russ Heath, who, after being assisted from a wheelchair to the podium, began by remarking, “What do you say when your pants are falling down?” Later in the evening, the Society presented one of its rarer mementoes, the A.C.E. Award (Amateur Cartoonist Extraordinary) to “Weird Al” Yankovic, a comedian described in Wikipedia as “singer-songwriter, musician-parodist artist, record producer, satirist, music video director, film producer, actor, and author. Known for his humorous songs that make light of popular culture and often parody specific songs by contemporary musical acts,” he aspired to work at Mad and has also drawn cartoons on occasion, hence the award. The NCS “division awards” (which are sometimes erroneously referred to as “Reubens”) are listed below with the names of the winners and finalists in each category. The jurying for the Division Awards is accomplished by the NCS chapters, whose members select in the assigned categroy three finalists, of whom one is designated the winner (but not announced until the presentation at the Reubens Banquet). All finalists appear as nominees in the months before the awards are presented, and because being nominated for any of these awards is a distinction in itself—the considered judgment of one’s peers—I’m listing here the nominees as well as the winners in each division, identifying the latter with an asterisk before their names; those with two asterisks were not present to receive their awards. Here’s this year’s list—: Editorial Cartooning —Clay Bennett, Adam Zyglis, *Mike Ramirez (two liberals and one conservative, Ramirez); Newspaper Panel Cartoons—*Dave Coverly, Speed Bump; Scott Hilburn, Argyle Sweater; Mark Parisi, Off the Mark; Magazine Cartooning—*Matt Diffee, Bob Eckstein, and Mike Twohy (because all are New Yorker cartoonists, which is typically the case, presenter Brian Walker referred to this Division as “the New Yorker Division”); Comic Books—*Sergio Aragones, Sergio’s Funnies; Jay Fosgitt, Bodie Troll; and Chris Samnee, Daredevil; Graphic Novel—Dan E. Burr, On the Ropes; Rick Geary, Madison Square Tragedy (see Opus 319); **Andrew C. Robinson, The 5th Beatle; Comic Strip—*Isabella Bannerman, Six Chix (six women cartoonists rotate through the days of the week, each doing one strip a week; Bannerman is the only woman cartoonist to win this year); Terri Liebenson, Pajama Diaries; Mark Tatulli, Lio.; Online Comics: Short Form (aka single-panel gag cartoons)—Jim Horwitz, Watson; *Ryan Pagelow, Buni; Mike Twohy (New Yorker Online); Online Comics: Long Form (aka comic strips, serial graphic novels)—Jenn Manley Lee, Dicebox; Dylan Meconis, Family Man; Eddie Pittman, Red’s Planet; **Jeff Smith, Tuki–Save the Humans; Book Illustration —Matt Davies, **William Joyce, C.F. Payne; Advertising/Product Illustration—Cedric Hohnstadt, Sean Parkes, *Rich Powell; Greeting Card—Glenn McCoy, *Park Parisi, George Schill; Newspaper Illustration—Bob Eckstein, **Miel Prudencio Ma, Dave Whamond; Magazine Feature/Magazine Illustration—Daryll Collins, Anton Emdin, *Dave Whamond; Television Animation—Craig McCracken, “Wander Over Yonder”; **Paul Rudish, Mickey Mouse Shorts; Douglas Sloan and Art Edler Brown, “Dragons: Riders of Berk”; Feature Animation—Jonathan del Val, animator of Lucy in “Despicable Me 2"; Michael Giaimo, production design, “Frozen”; **Hayao Miyazaki, director “The Wind Rises.” Of the 15 division award winners, 6 didn’t come to the event; that’s 40% no-shows, people who didn’t think the award significant enough to appear to accept it. Andrew Robinson, however, sent a videotape that was played when he won. No-shows

have long been a tradition for the Division Award

THE FORMAL CLIMAX OF THE EVENING is the presentation of the Reuben, the name of the trophy given to the “cartoonist of the year.” The official name of the winner in this competition is “best cartoonist of the year” or “outstanding cartoonist of the year.” But that designation has always irked me. As a general rule, the adjective is best ignored and discarded. As a purely semantic matter, “best/outstanding cartoonist of the year” implies that the recipient has done something in a given year that levitates him above his peers that year. For most of those who’ve won the Reuben, that’s scarcely true. Over the years, the Reuben was as often conferred for sentimental reasons as for excellence at the craft in a given year. Alfred Andriola (Kerry Drake), for instance, was an intrepid laborer in the NCS vineyard (producing the newsletter for several years) but he neither wrote nor drew his strip when he got the Reuben in 1970. And when Milton Caniff was the first to be named “cartoonist of the year” in 1947, it was as much for shaking loose of syndicate shackles with his landmark ownership of Steve Canyon and his guidance in the founding of the Society as for the excellence of his last year on Terry and the Pirates; consequently, Steve Canyon appears after his name in the annals of the Society, not Terry and the Pirates. In recent years, however, some dutiful factotum has sought to rectify this ostensibly illogical situation. Since Caniff won for his work in 1946—his last year on Terry—and since Steve Canyon didn’t appear in print until January 1947, logic suggests that his Reuben could not have been awarded for Canyon; it must’ve been for Terry. But logic didn’t drive the conferring of the award in those distant days of yesteryear. The “cartoonist of the year” accolade was presumed to result, indirectly—as the Oscar does with movie-makers and actors—in enhanced professional opportunities. In 1947, Caniff’s opportunities lay in the Steve Canyon direction, not in Terry of the past; so the name of his new strip was attached to his award. Pure commercial consideration. That nuance of history, however, has long been discarded by the current NCS regime. The short of it nowadays is that the Reuben is more likely a mark of the esteem of one’s cartooning colleagues than it is an objective evaluation of one’s work in a given year. Mostly, the Reuben is conferred upon a cartoonist whose work has been consistently of a high caliber, year after year, without distinguishing one year’s achievement from another’s. Hence, in my lexicon, the Reuben goes to “cartoonist of the year” NOT “best cartoonist of the year.” This year, however, is the exception to the rule (as I hope to demonstrate ere long): Wiley may well be the best of any recent year. The

trophy itself, a heavy metal statuette, was named in honor of NCS's first

president, Rube Goldberg, and the trophy is pure Goldberg. “If you have been influenced by Freud, you might say that the Reuben represents four cartoonists who hated their mothers for allowing them to become cartoonists and [who grope] for an acrobatic answer to the question of why sculptors and pretzel makers have so much in common. Or you might say that the Reuben represents the people of the world striving for a perfect balance to escape the same fate as the leaning tower of Pisa. You'd be wrong on both counts. “The Reuben is pure fantasy, including the bottle of India ink that Bill Crawford placed on the posterior of the top man to give the design a little more symmetry. If the Reuben has an underlying significance in its present form, I will say that I created it to keep it from looking like a golf trophy, an Oscar, or a statuette presented to Miss Kitchen Utensils of 1953. My only hope is that each recipient will look upon it as a symbol of the admiration and love of his fellow cartoonists.” But Goldberg's explanation was just another of his inventions. He didn't create the sculpture to serve as the NCS award: when he made it, he thought he was making a lamp. The light bulb screwed into the aforementioned posterior of the uppermost figure. Happily, fellow cartoonist Crawford saw this objet d'art in Rube's home at just about the time the Society was looking for a trophy to present to the “cartoonist of the year,” and he recognized at once that Goldberg's lamp was destined for greater things. He substituted a bottle of ink for the light bulb and made a cast for the trophy. The first to receive the Reuben in all its glory, trophy and fanfare, was the sports cartoonist Willard Mullin in 1954. Rube received the trophy named for him in 1967, three years before he died. (For more about “Rube Goldberg and NCS,” the founding thereof, visit Harv’s Hindsight for January 2001.) Before

the institution of the Reuben, the “cartoonist of the year” was presented with

a sterling silver cigarette case inscribed with the characters of Billy

DeBeck’s comic strip, Barney Google and Snuffy Smith. When the Widow DeBeck died, the award was suddenly unfunded, and NCS went looking for a successor, finding, as we’ve related, a suitable substitute in Rube’s lamp. Subsequently, all Barney winners were presented with Reuben trophies for the sheer sake of symmetry or euphony or some similarly musical reason. By the custom of the awards banquet, the Reuben is presented by the oldest Reuben recipient present—for years, that’s been Mort Walker (who won in 1953 for Beetle Bailey), but he was unable to attend this year; hence the next in age and dignity, Mell Lazarus (who won in 1981 for Momma and Miss Peach), presented the trophy this year to Wiley Miller, whose unique achievements in on the funnies pages of the nation’s newspapers exceed even the customary high standards set by previous Reuben winners—as you will quickly discern by reading our PROfile of Wiley (his signature name) which follows this Reuben Report. Taking the podium to receive the trophy, his cherubic face aglow, Wiley began a graceful acceptance speech by noting that it was “a once-in-a-lifetime award.” He probably thought he was speaking figuratively, but it is also true literally. Only a handful of cartoonists have won twice (Milton Caniff, Dik Browne, Charles Schulz, Pat Oliphant, Jeff MacNelly and Bill Watterson), and after Watterson won in 1986 and 1988, NCS adopted a “one to a customer” policy. Never again will two Reubens decorate the mantlepiece of some cartoonist’s domicile. Figuratively, Wiley was expressing the thrill and the honor he felt at finding himself among a distinguished roster of the profession’s most noted practitioners. Winning the Reuben means adding one’s name to a seven-decade line of great cartoonists, Wiley later told ComicRiffs contributor Tom Racine, and “to be part of that pantheon is very important. “At my age,” he continued, “I’ve been around long enough [to know] that this doesn’t mean I’m going to make more money or, like with an Oscar, I’ll get more plum roles. Pretty much the only ones who know about it are in [this] room. But it’s important [to me] to be part of that legacy.” At the podium, Wiley acknowledged that no cartoonist gets to this pinnacle in a career through his own efforts, alone and unaided. All of us, he allowed, have had help—namely, the cartoonists whose work we assiduously copied as youths and which inspired us later. He named in particular The Wizard of Id’s Brant Parker, from whom Wiley learned that the perfect comic strip was one in which there are no words. (Wiley also insists that comic strip artistry consists of blending words and pictures into a narrative and/or jocular comment that neither words nor pictures can achieve alone with other the other.) He finished his remarks by thanking his mother, relating an insightful tale of his youth. He, like most of us, spent his school days drawing pictures, often in the textbooks he was supposed to be reverentially studying. At some point, one of this teachers had endured enough of his pictorial shenanigans and summoned Wiley’s mother to lodge a complaint. Wiley

recalled his terror, waiting in the hallway outside the office into “What a bitch.” “At that moment,” Wiley said, “a cartoonist was born. Thanks, Mom.”

A Reubens Sunday Sunday at the Reubens was spent mostly aboard the USS Midway, a 1943-vintage aircraft carrier cum museum in San Diego Harbor, where we celebrated Memorial Day among mementoes of the service of military veterans both dead and alive. In the afternoon, various cartooners hung around on the flight deck, drawing pictures for civilians and signing book collections of their work. That evening, we all convened on the flight deck for dinner and dancing to the music of editoonist Michael Ramirez’s Deluz band. It was an okay experience, but as a former aircraft carrier occupant (USS Saratoga, 1961-63), I would have enjoyed a chance to ramble through below-decks haunts like the wardroom, disbursing office, and mess hall. Alas, that sort of free-ranging was not permitted. But we were encouraged to resort to a big piece of white paper to record our presence by limning our comic characters. I, as you can see from the adjacent photographic record, drew my nautical character Cumshaw, whose adventures had been rehearsed in the Sara’s monthly magazine.

Next year, NCS will meet in Washington, D.C., site of most of the terribly amusing national shenanigans, again over Memorial Day weekend.

Fitnit. I ran into Grant Geissman during the NCS festivities and asked him whether certain passages in his book, Feldstein: The Mad Life and Fantastic Art of Al Feldstein, had been, as I speculated in Opus 324, “watered down” to assuage the estate of Bill Gaines, who Feldstein claimed had written him, Feldstein, out of the history of EC and Mad. Geissman said he’d steered clear of reporting Feldstein’s bitterness in detail not in deference to the Gaines relatives but because he felt that to dwell on such matters would give the book a sour taste, and he wanted to avoid that in order to celebrate Feldstein’s achievement.

Non Sequitur Breaks New Ground Again and Again and Again

SOON AFTER Wiley Miller’s Non

Sequitur debuted February 16, 1992, Mark J. Cohen interviewed him

about his career and the genesis of the strip.

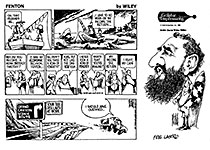

WILEY MILLER may be the most imaginative innovating cartoonist to achieve national syndication since the early days of newspaper cartooning when cartoonists were working without a net: with little or no graphic precedents and therefore without a clear idea of what forms their work could assume, they experimented wildly with page layouts and sequencing panels and varying characters for comedic effects. Finally, after a few years, the Sunday format of a sequential grid of panels gelled; and the daily strip format quickly emerged thereafter. With Non Sequitur, Wiley (to resort to his signature name) may be seen assuming the spirit of those early days of daring experimentation in both format and topic. But he didn’t reach that level achievement without serving an apprenticeship in the more traditional modes of newspaper cartooning. Wiley is a cartoonist because he has no choice in the matter. "As long as I can remember, I've wanted to be a cartoonist," he told Mark Cohen. "I grew up reading the comics with more enjoyment than normal, and it became a passion. I wasn't satisfied just reading the funnies, I was always reading, tracing, then copying the work of my favorites." David Wiley Miller was born April 15, 1951 in Burbank, California: “Ten pounds, 6 ounces,” he quipped, “—ouch.” When the Millers moved to Virginia, Wiley attended Langley High School in McLean. “My school lbus went by Bobby Kennedy’s house every morning,” he recalled. “Always wondered what it was like inside.” He cartooned for the school newspaper, and since Langley High School was brand new during his freshman year, he was the school newspaper's first four-year-cartoonist. (A few years later, Brian Basset, another of Langley's school newspaper cartoonists, also went on to success in both editorial and strip cartooning, in the latter category, first with Adam @ Home and then with Red and Rover.) Each year the school sponsored an arts festival featuring various speakers: actors, painters, musicians, and artists appeared before the students. During Wiley's sophomore year, Brant Parker of The Wizard of Id was a featured spaker. It was at this time that Wiley realized that cartooning could be done for a living. Wiley visited with Parker for an hour after his talk and got a lot of good, basic information. Wiley attended Virginia Commonwealth University, one of the finest art schools on the East Coast, where he majored in painting and print-making. After graduating, he enjoyed “memorable stints as a sign painter and assistant manager at a Pizza Hut” but finally entered the cartooning profession in an educational film studio in Los Angeles. Wiley kept up his contact with Brant Parker, who introduced him to editorial cartoonist Art Wood. Wood provided a contact which helped him land a job as the staff artist for the Greensboro Daily News and Record. On his own time, he was drew editorial cartoons. In 1978, Wiley took a position as the staff artist for the Press Democrat in Santa Rosa, California. One of the conditions of his employment was that he produce a daily editorial cartoon, and in 1979, Wiley's editorial cartoons and caricatures began syndication with Copley News Service. While at the Press Democrat, Wiley began work on a comic strip which featured a retired man named Fenton. Tribune Media Syndicate entered into a development contract with him in 1980, but after a contract dispute, the strip was left in limbo. In

1981, Wiley left the Santa Rosa paper but continued to syndicate seven

editorial cartoons and three caricatures a week for Copley while continuing to

develop Fenton for distribution by another syndicate. After exhausting

his own contacts, Wiley turned to his old friend and mentor Brant Parker, who

was able to help him interest Field Syndicate in the feature. On March 7,

1983, Fenton made its debut; it lasted through 1985, eventually

appearing in 125 papers. The San Francisco Examiner asked Wiley to draw a special series of two strips a day about Fenton attending the Democratic National Convention, which was held in San Francisco in 1984. It was extra work but it paid off unexpectedly: not only was the special series popular, but Wiley learned that Ken Alexander, the Examiner editorial cartoonist, was retiring. In December 1985, Wiley became the new editorial cartoonist for the paper. Then he promptly dropped his syndicated comic strip. It was a matter of principle. Through the years, Wiley has been quite outspoken about cartoonists drawing editorial cartoons and a syndicated strip at the same time. "For some time," he said, "it seemed that every new strip that came out was being done by an editorial cartoonist. The syndicates felt that editorial cartoonists were already developed talent because they were well-known and had predeveloped markets for their work. The syndicates used to take raw talent and offer a development contract so that a new artist could hone his skill and become ready for what most cartoonists had dreamed of all their lives—syndication! By hiring editorial cartoonists, they didn't need to offer development contracts." Wiley expressed a number of concerns about cartoonists producing both editorial and strip work at the same time: ■ Editorial cartooning and comic strip work are both full-time jobs, and a person can't do two full-time jobs well. ■ The two types of cartooning are two very different fields and generally the editorial cartoon suffers. Rather than being pointed commentary to make a person think, it becomes a gag-a-day panel, featuring weak topical humor. ■ If you work at two full-time jobs, you don't have the time to observe life and people in the real world, and you miss one of the best sources of material. ■ New talent has a harder time breaking into a limited field if editorial cartoonists take up two spots in the papers. "This is an extremely difficult profession to break into," Wiley observes. "It's easier to become a pro ball player than to become a professional cartoonist. Just look at the numbers. There are about 100 working editorial cartoonists, and right now [1992], there are 173 comic strips in production. Out of a population of 250,000,000, that's tough odds. And then if you have one guy taking up two of these very scarce spots, it just makes it that much more difficult for young talent to break in. "On purely ethical grounds," he continues, "and to maintain the quality of the work, do one thing—and do it well." As an editorial cartoonist, Wiley won several awards, including the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award in 1991. “Finally got to go inside Bobby Kennedy’s house,” he sighed in satisfaction. But a new day was about to dawn.

SEPARATED FROM HIS FIRST WIFE in 1987 (and later divorced), Wiley became a patron of a local San Francisco establishment—a real life Cheers, a very open, brightly lit place with a family-like feeling. It was more comfortable than sitting home alone in front of a TV set. As he became known in the place, patrons started asking him for drawings on cocktail napkins. "Ball point pen on napkins just didn't work," Wiley said, "so I started to bring along good paper and pens. I really began to enjoy it. My drawings were free-wheeling and uninhibited. They featured local patrons, waitresses, and bartenders. I called them Bartoons. "During a New Year's Eve party I was showing my Bartoons to some of the guests. I met Victoria Coviello at that party, and on New Year's Day a year later, she became my wife." Over the next two years, Wiley built up an extensive portfolio of these cartoons and, on a whim, sent a few to Playboy, where, much to his surprise, four of them were purchased. Subsequently, during an economic crunch, the Examiner cut Wiley to three cartoons a week and moved his work off the editorial page and onto the op-ed page. During this troublesome time, Victoria kept saying that Bartoons deserved a wider audience and that Wiley should develop them for syndication. Wiley took his ideas to several syndicates and they all said about the same thing: "You need to come up with a strip that has one or two central characters featuring the family, work, or school, that will provide a humorous look at living in the nineties. That's what editors want." But Bartoons had no recurring cast. Wiley felt that if he followed syndicate directions, syndication might be a possibility, but he would be doing what everybody else was doing. "I came up with several different formats but none of them were satisfactory," he said. "I found that I was trying to force my ideas into an uncomfortable format to please the syndicates and to conform to what they thought the editors wanted.” After years of fighting editors, Wiley finally decided that they were not likely to change. So he had to. His conclusion: "It's up to us, the creators, to work within the dimensions that are given. We have a certain amount of space, and it's up to us to make the best use of it." And that's what he set out to do with Non Sequitur. Said he: “I had a whole portfolio of free flowing, single panel cartoons, but no syndicate wanted to handle a single panel, so I modified them to fit standard comic strip dimensions. And it worked." Re-tooling his Bartoons and new ideas, Wiley drew the single panel cartoon strip-wide to fill the space customarily allotted to a traditional comic strip of several panels. He came up with the name Non Sequitur (Latin for “it doesn’t follow”) because in the beginning one strip did not “follow” another. One day's strip had absolutely nothing to do with the next day's. There was no central character or theme. No setting, no time frame. Each installment stands alone. Anything goes. Perfect for free-flowing generation of gags. “From its inception,” Wiley explained in 2005's Non Sequitur’s Sunday Color Treasury, “I wanted Non Sequitur to be able to strike out in any direction creativity took me. I figured that would stave off the burnout factor indefinitely, as this format would allow me to keep reinventing the feature.” Turns out, he was right: “When I start feeling the creative juices slowing down in one area,” he said, “I strike out in another direction, almost like creating a whole new comic strip. This makes it more fun for me and keeps the strip from becoming predictable.” The syndicates to which Wiley submitted Non Sequitur all said that the writing and artwork was excellent but they wouldn't buy it. "If the writing and artwork are excellent," Wiley asked, "what more do you want?" They answered: "We want a strip with central characters and a storyline that provides a humorous look into life in the nineties." Wiley felt that a central character and theme would weaken his concept and take the soul out of his idea. Finally, he submitted his strip to the Washington Post Writers Group. He was hesitant to do so because they were not known as a syndicate on the look-out for new comic strips to sell. WPWG’s Alan Shearer called Wiley the day he got his submission package. "Alan was taking the same approach I did," Wiley said. "And it was a good marriage. Shearer didn’t try to guess what the editors want. He would rather have something well done, different, and creative. You are selling a product. If ten similar products are available, the last thing an editor needs is one more of the same old thing. "The more variations there are on a specific theme," he continued, "the weaker the theme becomes. If you have something different and salable, there is no recession." It appears that both Wiley and Shearer were correct. At the time of Non Sequitur's debut on February 16, 1992, it was in eight of the top ten markets; before the strip was a year old, it was in 150 papers, and Random House had agreed to publish a reprint volume. And as the first year of Non Sequitur drew to a close, the National Cartoonists Society dubbed it the Best Newspaper Comic Strip of the Year. An auspicious beginning. And it continued: NCS named the feature, oddly enough, the Best Newspaper Panel Cartoon in 1995, 1996, and 1998. For a long time, Wiley was the only syndicated newspaper cartoonist to win in both strip and panel divisions—with the same feature. Wiley would leave WPWG for Universal Press syndicate in 2000, but by then, Non Sequitur —in all its adventurous variations (about which, more in a trice)—was well established. With that experience behind him, Wiley’s advice for aspiring cartoonists is not surprising: "Do your own material. Don't try to manipulate your ideas or format just to get syndicated. The real success stories in this business don't go along with what the syndicates think they want; they buck the trends and break new ground. It is just as true today as it was when Charles Schulz broke new ground over sixty years ago. There are trend setters and trend followers. You should follow trends to get experience and set trends for success.” Don’t be afraid to try something unconventional. Fear, he said, is the syndicated cartoonist’s greatest enemy. Fear of change, of something new. And syndicated cartoonists work in a milieu that actively resists change because they fear the consequences. Interviewed just after the Reubens weekend by Tom Racine for ComicRiffs, Wiley put it emphatically: “Cartoonists get browbeaten by the suits,” he said. “You’re told: ‘This is the way it’s done.’ Being the obstinate SOB that I can be, I always ask: ‘Why can’t we do this? Why can’t we do that?’ I’m always trying to push things,” he concluded, noting that he doesn’t ask permission before experimenting. “I haven’t had to apologize yet.”

WILEY THINKS of Non Sequitur as having "a panoramic look." Indeed, he deliberately designed the feature for that effect. When he re-formatted his traditional two-column single panel Bartoons because newspaper editors wanted cartoon features that would fit the familiar grid of the funnies page, he began thinking in terms of design, and much of his subsequent career can be seen as adventures in design. "The whole point of my design concept of the strip itself was to maximize the use of the space given," Wiley explained when I interviewed him in 1992. "I approached it as a design job. I have this space. How do I utilize it? It's exactly what I did with my editorial cartoons: I utilized the space. Composition is very important. It's one of the first things I tell kids that come seeking advice. I tell them that the physical part of cartooning is a form of abstract art. Before you can abstract something, you must know the fundamentals. And all of the rules of line and composition that apply to any painting or drawing apply to a cartoon—comic strip, editorial cartoon. Composition is very important. Utilize the space, make it readable. "Doing something as incredibly simple as leaving off the border line around the drawing produces an amazing result," he continued. "It's incredible how that expands the drawing—" I agreed: "You get to claim the space above and below the strip." "Right. And that's the thing. It's utilizing white space. Just because you have space there doesn't mean you have to fill it up with stuff. Use that white space to emphasize your point. That's what composition is." "You

really make that space work," I observed, and by way of illustrating my

point, I drew attention to the cartoon posted nearby and the placement of the

speech balloon: "You put it there because you want the reader to move

through this horizontal reading experience, left to right." "Right," Wiley said. "That was very deliberate. Your eye is going to be attracted to the dark first [the briefcase], and because in our culture you read from left to right, you start off left and see this woman— okay, what's she talking about? It's a rather innocuous gag. The gag isn't what she's saying." "Right," I agreed, "—it's the next element." "And this is another of the basic problems I think a great number of comic strip cartoonists have today," Wiley went on, remembering, no doubt, Brant Parker’s notion of a perfect comic strip. "They are too heavily reliant on the written word. There's very little visual humor being done. Part of that is because there isn't much room for visuals. If you look at the old days, there was a great deal of wonderful artwork with emphasis on action and so on. Again, this is exactly what I did as an editorial cartoonist: it was the visuals—the metaphor thing—that emphasized the point of the issue or my stance on the issue. I do the same thing here—utilize the visual and not rely on the written word. I use the written word as the setup. It puts you in one frame of mind, and then I jerk the reader in another direction with the visuals." I

agreed again: "I've often said that the very best cartoons—magazine

panels, strips—are ones that don't make sense either as pictures or as words. They

have to be together, the picture in conjunction with the words, and then it

makes a kind of sense that neither make alone. Here's a perfect example of

what you're talking about in the visual aid just at hand. "In the visual," Wiley said. "In the visual," I said. "To me, the classic difference between an editorial cartoon and a comic strip is that an editorial cartoon is essentially a metaphor, a visual metaphor. A comic strip is timed visuals in sequence. Timing is the essence of the comic strip mode. So when I first contemplated a single-panel strip like Non Sequitur, I didn't think it involved timing at all. But yours does. Because you've stretched the visual exercise—the act of looking—over the length of the strip-size panel." "Instead of doing it in panels." "Are you conscious of doing that?" "No, not really. This is something that is done by feel, by experience—" "And you know you want to fill this space this way," I said. "Again, it's composition, as you said." The

long horizontal dimension permits considerable flexibility in delivering a gag.

In the cartoon posted near here, the punchline is not at the end of the panel's

panorama: it's at the beginning—the woman with the vacuum cleaner. "You do it by feel," he said. "Part of the gag is the guy on the right. He's out there shoveling and he's got this perplexed look—how's she do that? So it just kind of circles around. That's very much a New Yorker cartoon effect when I try to do that. I try to get more sophistication of thought, of cartooning, into comic strips, rather than the usual comic strip fare—filled with puns of some kind. And it's all been pretty much done over and over again. Today's comic strip reader is generally more sophisticated. The mere fact that someone is holding a newspaper in their hand in this day and age means—in this day and age—that they're more sophisticated. So that's what I'm gearing towards." More

evidence of how the strip-wide single panel “comic strip” works can be found in

the accompanying gallery of Non Sequiturs (vintage material admittedly,

but, as Spencer Tracy would say, “cherce”). “Sometimes Non Sequitur is pretty topical,” I said: “Do you work on a short deadline?” “No, I'm working further ahead,” Wiley said. “When Fenton first started, I was about a year ahead. I let that lapse because I wanted to be more topical. But the only political material I'll be doing in Non Sequitur is about politics itself, not about Clinton or Bush or anything that specific. So I don't need to be [that close to current events]; and I'm trying to work as far ahead as I can. Right now [December 1992], I'm through the middle of March on the dailies, and I'm into April on Sundays. For two or three weeks, I'm going to work on Sundays only and see just how far ahead I can build up. Right now, I'm doing a lot of holiday material for next year—Christmas stuff for 1993.” “Great,” I said. “I've always thought you should work far enough in advance that you can do the gags while you're living the season. But most people don't get that kind of time.” I asked him about his daily routine. “I didn't really have a daily routine on this until we got here,” Wiley said. “I was still working at the paper and doing that, so I was pretty much doing strips on the weekend. But after being here for a couple of months, I wasn't getting the work done, so I felt I had to put myself on a schedule to get the work done that I required of myself. So what I do— my best working time, when my brain is freshest, is in the morning, so I'll go to work—get up, read the paper, watching the ‘Today’ show and all that—have a cup of coffee—then get right to work, writing, developing, and sketching out cartoons. I approach Non Sequitur exactly the same way as I did my editorial cartoons. I read newspapers, watch tv; what am I going to talk about? What issues? So in one sense, doing this is more difficult than the average comic strip because I don't have a cast of characters to fall back on; I can't do a gag within the strip.” I agreed: “You can't do personality gags, gags based upon the personalities of your characters.” “Right, right—because it's not there. But on the other hand, that's why Non Sequitur is so popular: it has an immediate impact. I've got more response from this strip than in all my years of editorializing or Fenton or doing magazine cartoons because it hits home. I'm talking about real issues. And so people recognize these and it really hits home with them, and because it's a visual, it has a more immediate, visceral impact rather than all the things leading up to it. I've had so many more requests for originals and copies than anything I've ever done.” For the first few years, Non Sequitur was more political than it eventually became, once Wiley settled in. He pencils the strip early in the day and saves the inking for later. Said he: “The inking of the cartoons is kind of the bonehead, nuts-and-bolts mechanical part of it, which I don't really need the creative process for, so I can do that anytime. I can ink the cartoons later on in the day or at night, watching TV or watching a ballgame or something—I'll just ink it.” [Using rapidograph pens mostly in those days.]

BY 1992 WHEN I INTERVIEWED HIM, Wiley was on the cusp of producing the daily strip in two formats. Using the same artwork, he could crop the feature to make it a two-column single panel cartoon or a strip-wide single panel cartoon. The trick was in the artwork’s point-of-view: typically, he pictures scenes from slightly above ground level, and that makes it fairly easy to convert the horizontal strip format to the more vertical two-column cartoon format. It was the first in a series of maneuvers Wiley would conduct over the years, seeking greater circulation by addressing a need he saw manifest in newspapers. Offered in two daily formats, Non Sequitur enhanced its appeal to editors: they could run it as a panel cartoon or as a strip. The greater the flexibility Wiley offered, the greater potential for increasing circulation. By then, he was also well into a similar design experiment with the Sunday strip. He'd been doing the one-third page standard with a couple throw-away panels at the beginning for papers that used the feature in the smaller quarter page format. But few papers, he realized, use the third-page; and the reduction of the remaining panels for the quarter page is so great that the artwork suffered. So

Wiley redesigned his cartoon as a two-panel feature. As we see in the

accompanying sample, at the top is a large panel; at the bottom, a narrow strip

of a panel. Said Wiley: "This way, there's very minimal reduction for the quarter page standard, and you have the small title panel box next to it. Again, using the space allotted for maximum effect. And it gives newspapers an incentive to run a third page: if they run a third page, they get the bonus cartoon, two for the price of one.” And, even more important for the cartoonist, said Wiley: “It maintains the quality of the art better.” After a year's trial, Wiley said he’d re-evaluate the new design: "If there aren't enough newspapers running it in the third page format, then I'll go strictly to the quarter page standard and stop doing the bottom panel altogether." Eventually, he would tinker again with the Sunday format, this time, making a genuinely drastic change. Before that, however, he aspired to better color for Sundays. He talked American Color, producers of most of the country’s color Sunday strips, into experimenting with “process color.” Process color is the way color photographs are reproduced in newspapers; color comics, on the other hand, were, at the time—and still are pretty much— printed in flat primary colors, screened mechanically for pink and green and other colors. Process color can reproduce gradations of hue; in flat colors, no such shading is possible. Wiley ran into some resistence, but in early 1994, Non Sequitur began appearing in subtly hued shades and revolutionized color comics for newspapers. Two years later, Wiley was telling a story in color that continued from Sunday to Sunday. A few months later, in March 1996, he introduced Homer the Reluctant Soul, a recurring character whose adventures—being reincarnated and sent back to earth to live another life—would continue from Sunday to Sunday for a month or more at a time. In Non Sequitur’s first year, Wiley had done a few strips about a French Canadian named Pierre of the North; he’d been persuaded by editors at his syndicate to give up the character when they started hearing rumors that French Canadians were upset, thinking the character was ridiculing them. Wiley brought Pierre back years later (without getting permission). When he launched Homer, he didn’t hesitate: he plunged eagerly on. The possibilities seemed endless: “I could readily see that it could go on forever, as the whole point of Homer was theat he would come back to life as a completely different person, male or female, in any period of time in history. Each storyline would be like a whole new comic strip.” His editors were reluctant; they raised objections. Wiley went ahead, and the first Homer sequence was enthusiastically received by his readers. Homer was so popular that Wiley brought him back again and again—and eventually launched a separate Sunday only strip starring Homer. It ran for just a little over a year. Wiley had to give it up: he couldn’t do two strips and still have a life beyond the drawingboard. Another recurring character showed up in 1998 in a Sunday series called “Raising Kane,” intended as a spoof of comics fans who couldn’t move on after the cessation of Calvin and Hobbes. But the misbehaving Kane was so popular, he acquired a continuing life of his own in Non Sequitur. Kane was followed by Danae, a pre-adolescent girl with a pessimistic view of the world (“but not of herself,” as Wikipedia has it). Other characters followed. Joe Pyle, Danae’s father. Then Lost Leonard and Obviousman and the Gravesytes, a homage to Charles Addams’ erie family. Then came Offshore Flo, owner of Offshore Diner in Whatchacallit, Maine, whose most constant customer is a lobster fisherman named Captain Eddie, who, in his cups (his usual condition) tells tall tales of encounters at sea with monster lobsters, fish, or alien beings. Each of the characters precipitated storylines of their own. Then, in 1996 when he introduced the separate Homer strip, Wiley performed his most startling maneuver: he began drawing his Sunday strip in a vertical rather than horizontal format. At first, the verticality emphasized Homer’s permanent residence high above earth, which he visited in a succession of lives. But there was a strategic commercial element in the new format. Increasingly, newspapers, seeking to cram as many strips into the Sunday funnies as possible, opt for ever smaller sizes, going from quarter-page size to a fifth or even a sixth of a page size. To accommodate the greater number of strips on a page and to compensate for the smaller size, newspapers discard the traditional throw-away panels and publish just the bare bones of the strips. Reducing

strips in this fashion leaves an unused “column” at the edge of And then in 2000, he introduced the same format in Non Sequitur and continued it. “The bonus that I didn’t foresee was how flexible and fun this dimension is to work in. By having the art designed for this space (as opposed to using static boxes stacked one on top of the other), I had endless possibilities to play with, as the art would be done in a far more dynamic way than what’s afforded with the traditional horizontal format.” Moreover, as he told me later, the format doesn’t give away the joke before its time. The reader is forced to wait until the end—the bottom of the vertical—for the gag. The traditional horizontal comic strip Sunday format consists, typically, of two tiers of panels, and a reader reaching the last panel of the uppermost tier could drop his/her gaze to the last panel of the lower tier, seeing the punchline before he/she should. With the vertical format, Wiley was more confident that he was preserving perception of the punchline until the very end, where it is supposed to take place. At the elbow of your eye, we have posted four examples of the vertical Non Sequitur to show just how the greater flexibility of the format can enhance the narrative. The format also presents challenges: which pictures should be larger for dramatic impact, where to position caption blocks and speech balloons for comprehensible reading order.

The first two examples—one featuring the conclusion to a Captain Eddie whopper; the other, an episode at the Gravesytes—demonstrate how the format permits Wiley to draw larger pictures when the storyline demands pictorial emphasis. And he floats blocks of captions down the scroll, staging their appearance in reading order as carefully as he positions the pictures and apportions space to them. The vertical format encourages more than flexibility in layout. As we see in the next example on the second visual aid with an appearance of Homer, Wiley floats speech balloons both across the panels in a conventional manner and unconventionally down the strip. In the second panel, Duncan the dog’s comment comes after the remarks of the other two personages, the position of the speech balloon— down the strip—indicating the order of reading. The format allows for small panels as well as large ones when a diminutive size emphasizes the message. The third panel is somewhat larger than the others, underscoring the cavernousness of the setting; in sharp contrast, the next panel is tiny—focusing intimately (so to speak) on the cleric’s apparent embarrassment. And in this strip’s opening panel, the over-all verticality adds thrust to the sudden rise of Homer and Duncan into Heaven from the earthy depths below. In our last example—another Homer strip but not next in sequence— the format gives Wiley a opportunity to draw a viking ship in discernible detail. The narration by Homer, however, follows a conventional pattern—simple chronology of the non-floating sort. Despite his inherent bias as a cartoonist for the visual element in his work, Wiley sees cartooning as writing. Writing in the sense of narrative, I gathered—not just words strung together. “You should write what you know,” he cautions aspiring young cartoonists. “All it is, is observation.” He elaborated: “Writing is the most important part of cartooning. That's the most essential part. People don't realize that. Especially editors; they don't understand it. A cartoonist is a writer. Anybody can draw. Anybody can draw a silly cartoon, a silly picture. A silly picture is not a cartoon. We are conveying a thought, presenting a perception. We are making a comment, not necessarily a big comment on a big issue—but an observation. “Cartoonists are essentially columnists,” he continued, “—we perform exactly the same function, we just work in a different format. Except for the so-called new-wave cartoonists who just write everything; with them, the drawing is superfluous. That is my biggest problem with the so-called new wave cartoonists; they rely so heavily upon the written word. And their drawings are innocuous. They're redundant.”

WITHIN A COUPLE YEARS, Wiley’s ever-questing, constantly innovating creative mind had launched another comic strip. Us and Them, beginning July 30, 1995, explored two complementary (or perhaps contradictory) concepts. It explored the issues and events of everyday life from two divergent points of view—the male’s perspective, and the female’s. “Our perspective,” as the syndicate brochure explained, “and theirs.” To add spice to that concept, the second complimentary one was that the strip would be produced by a male, Wiley, and a female, Susan Dewar, working in tandem. “Think of it as time-sharing cartooning,” the brochure went on. “Two cartoonists, one male, one female, exploring their views onlife, the opposite sex, and the foibles of their own gender. Two writers with complementary styles, whose cast of characters appear on alternating days.” Wiley’s

central character is Joe Pyle, a recently divorced radio talk show host;

Dewar’s, Janet George, a single mom who works at home as a tabloid newspaper

columnist. The strip lasted until 2000, but Wiley begged off at the end of March in 1997, his role taken by Milt Priggee, who, in his day job, is an editorial cartoonist. But Wiley continued to indulge his passion for experimentation in Non Sequitur: Homer and the vertical format were just on the horizon. To sum up by way of deriving an obtuse lesson from Wiley’s endeavors: by the time he got the Reuben, his strip was 22 years old and appeared in over 700 newspapers, and Wiley had developed characters in Non Sequitur and done character-driven storylines—both aspects of his art that he’d initially devised the strip deliberately to circumvent—plus experimenting gleefully with format and a wide range of subjects suitable for comedy, all the while still gravitating occasionally back to gag-a-day strips without continuing characters. In short, he’d done it all, and he’d done it by continually indulging his creative impulses, ignoring those who chorus “it can’t be done” and having a great fun time doing the thing he loved. What a creative cartoonist. Just the sort that should get the Reuben.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping STRANGE AND

AMUSING. Stephan Pastis’ Pearls Before Swine continues to construct elaborate assaults on the sensibilities of its readers. Young people wouldn’t be bothered by such shenanigans as this strip’s, but newspaper readers aren’t, as a rule, young: newspaper readership skews elderly, to people 55 and older to be exact. But the thing that amuses me about this strip is the stick figures in what purports to be Pastis’ “favorite online strip.” Naturally, it goes without saying that his favorite strip is one with stick figures in it—a strip a lot like his own, as I’ve said on other occasions. In fact, it may be his own. Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grim deploys a comedic device akin to Summers’ in our opening fusillade. But Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy I just didn’t get at all. At first. I read

this Tuesday installment but I’d missed the preceding day’s which, as we’ll see

in our next visual aid, explains it all. After Wednesday’s strip (which appears here second from the top), I realized I’d missed something, so I went back and found Monday’s strip (which appears at the top of the accompanying visual), which elucidates. Thus: the whole week of Fuzzy is supposed to represent Conley’s lazy irresponsibility. He has resorted to using a week’s worth of Pastis’ Pearls, which had been mistakenly sent to him by the syndicate. So he just pastes Satchel’s face over panels of Pearls and passes the strip off as his own. For the entire week, all of which we see here. None of these strips strike me as particularly funny. And whatever humor resides in them depends entirely on the reader knowing both strips. That’s the hazard strip cartoonists run by giving cameo appearances in their strips to characters from other strips. It’s been done occasionally over the years—but rarely until Pastis started making a regular practice of it. The jokes invariably depend upon our knowing a good deal about the personalities and peculiarities of the strip being cameo’d. Hence, the risk. What if my newspaper runs only Fuzzy and not Pearls? Then the lame jokes in this week’s worth of Fuzzy will not only be lame, they’ll be incomprehensible. The cartoonists involved here are undoubtedly friends, and they are surely having a great time with Conley borrowing Pearls characters. But the cartoonists are probably the only ones reading Fuzzy this week who find it very funny. This week’s Fuzzy is, admittedly, at the extremity of the cameo dodge. But however much fun Conley and Pastis are having, one of them is basing his jokes on the other’s comedy. It’s not plagiarism, but it is poaching. And the last strip on exhibit here? Just to remind you that I’m done making hairballs for today.

JUST TO PROVE

that it doesn’t take much to amuse me, here’s a Blondie Sunday in which

almost nothing happens. In Sally Forth, it’s the t-shirt that capitivates. “You’re so party, let’s go dancey.” Where’d that come from? Perfect for a light-hearted mood. Finally, Dagwood again. We don’t often seem him in such violent throes of emotion or reaction.

CONTINUING

OUR SURVEY OF TABOO-DEFYING urinating comic strips, here’s Peters’ Mother

Goose and Grim in which Grim does what doggies do. To comprehend Grim in the next exhibit, I must tell you that in the previous day’s strip, Grim swallowed Mother Goose’s lottery ticket—hence, the need, here, for him to, er, discharge it. None of which would have been permitted forty years ago. The next one, I don’t get at all. Help.

MORE PISSING

JOKES in the funnies of the 21st century, none of which would have

been permitted in mid-20th century comic strips. In The Knight Life, Keith Knight visits a restaurant run by animals and gets a rude surprise. A bathroom joke, not exactly a urinating gag—but bathrooms, particularly the toilet parts, were verboten in Olden Tymes. Brian Crane’s Pickles isn’t about bathrooms or urination—but it’s in the neighborhood.

QUOTES & MOTS “Dictators don’t crush people’s hands because the cartoons they draw have no impact.”—Matt Bors “Always go to other people’s funerals, otherwise they won’t come to yours.”—Yogi Berra “Every day, people are straying away from the church and going back to God.”—Lenny Bruce

COLLECTOR’S CORNICHE Welcome to our sentimental section where I muse and marvel about antique volumes on the shelf and rare finds in old bookstores and the like. Nothing major. Skip over this if you’re busy.

HERE’S A RARE

ITEM for your scrapbook—a magazine gag cartoon by the fabulous Jack “Plastic

Man” Cole, published long before Plastic Man started in Police Comics in August 1941—in Collier’s magazine for September 2, 1939. Cole had

arrived in New York in 1936, hoping to freelance gag cartoons to magazines.

After a year’s abysmal luck, he went to work for Harry “A”

G.I.

Joe Comics. I’ve

been trying to learn who drew this feature. And I finally know: it was Henry

Sharp, ID’d by Saun Clancy at the Comics History Exchange on Facebook.

Henry Enoch Sharp is listed in the Jerry Bails and

READ AND RELISH: UNANSWERABLE QUESTIONS DEPARTMENT If love is blind, why is lingerie so popular?” Why is a man who invests all your money called a broker? Why is a person who plays the piano called a pianist but a person who drives a race car not called a racist? Why isn’t 11 pronounced onety-one? If natives of Poland are called Poles, why aren’t natives of Holland called Holes? Do infants enjoy infancy as much as adults enjoy adultery?

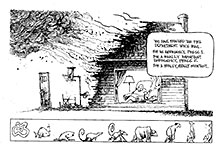

FINAL FLING PORTFOLIO (1978-82) What I laughingly call “my cartooning career” (i.e., when I was drawing funny pictures in the hope of earning money by selling them to magazines) took place in two installments: in the fall of 1959, right after my unrumunerative cartooning career as a campus cartoonist (about which, some day in the not so distant future, I’ll annoy you in tedious detail), and again twenty years later, when I freelanced from home, sending batches of 20 cartoons around to magazine cartoon editors for 3-4 years after having gained a Ph.D. I probably have 700-800 of these specimens tucked away in the Rancid Raves Book Grotto, and I’ve been posting the ones I like best on my Facebook page, if you’d care to drop in there occasionally (Robert Harvey is the tag). As

I’ve said before (in Harv’s Hindsight for February 2012 when I

discussed my nefarious freelancing career), I wound up drawing mostly cartoons

with barenekkidwimmin in ’em because those sold better than the “general

interest” (i.e., inoffensive “family” comedy) cartoons. So there’s a certain

amount of nudity in the cartoons I’m posting on Facebook. The one at hand is a

particularly provocative example. I’m a little hesitant about this one. The gag is okay, but the drawing, now that I view it three decades later, seems a little unabashed. I always went for candor in rendering a gag, so I just blurted out the whole Nudist Colony nudity thing, the unadorned fact of it. I suppose it would be possible to pose the guys here in a way that would obscure or obliterate the view of the one guy’s junk, but, under the compulsion of unrelenting naturalism, I didn’t. I guess I thought if the women were going to be totally naked and unashamed, so should the men. I think the central woman’s playing patty-cake with her chesticle is visually inventive, and if you’re drawing girlie cartoons, you’re always faced with the undeviating sameness of it all. How do you insinuate a little visual variety? The akimbo left foot is another gesture in the same direction. I like the little people cavorting in the background and the foreshortening of the right arm of the guy on the left. And the shading. Notice that there are three grades of vertical lines—thin, medium, and relatively fat. When

I posted this cartoon with the foregoing discussion on Facebook, The next day, along came Bill Whitehead, whose Free Range panel cartoon seems serendipitously a propos.

DURING MY FINAL FLING, I worked with gag writers. Coming up with ideas for cartoons has always been the most difficult part of the job for me, so when I heard there were legions out there of people who wrote gags for cartoonists, I dashed right out and got one. Eventually, several, who regularly sent me gags on slips of 2x4-inch paper. I’d select the jokes that I thought were funniest (and that I wanted to draw the pictures for) and return the rest. For every cartoon I sold, I sent a percentage of the revenue to the guys who wrote the gags. I think it was 10-15%; I eventually raised it to 25% in the hopes that a higher share would stimulate better gags. But who can say? Humor is so subjective that what seems “better” to me is still, maybe, only mediocre to you. I

eventually compiled a pretty good sales record: better than half of the girlie

cartoons sold; not so good with general interest cartoons, so, good capitalist

that I am, I obeyed the law of supply and demand, and by the end of the Fling,

I wasn’t doing any general interest cartoons at all. Succumbing to the

aforementioned capitalist principle, I drew lewd ladies in their birthday

raiment. Enough preamble: on to the cartoon at hand—which, despite the

preamble, is a general interest cartoon. Here’s what the gag writer sent me for this one: Employee of ACE Kennels says to visitor he is showing around as they approach sign—Do Not Litter: “And this is our birth control center...” Casting was the first order of business. Who would the employee be showing around? Well, how about a father and his son, looking to buy a pet. Composition is next. It seems to me now that it’s funnier to have the “Do Not Litter” sign on the left because it takes a few seconds for the connection to “birth control” to sink in. The delay postpones the “surprise” of the connection. The surprise prompts laughter, and I think the delay enhances the surprise and thus the laughter. I admit, though, that when I saw this cartoon for the first time in decades and picked it to show here, I quickly took in the scene, then read the caption, then went back to the picture, looking at the dogs for some evidence of birth control. Fact is, I doubt that most readers would pick up on the sign when first taking in the scene as a whole. I suspect that I thought, back then, that the reader would actually read the sign before reading the caption. Now, with my own experience as insight, I think the composition would have been better if reversed. If the composition were reversed, the employee’s gesturing hand would, in effect, be pointing to the “Do Not Litter” sign in reading order, hence making deciphering the cartoon easier, quicker. No confusion either. But at the time I did this, I wasn’t thinking that. Costuming was also a consideration, of course. The father and his son, casual dress. The employee, in some sort of working duds—coveralls or jumpsuit or some such.

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Sometimes happy, sometimes blue, But I’m so glad I ran into you--- Tell the people that you saw me, passin’ through

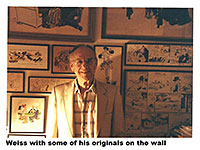

Morris Weiss, 1915 - 2014 UNDER THE

HEADING “Morris Weiss, Mickey Finn, and the Palooka,” the article that follows

appeared in Jud Hurd’s Cartoonist

PROfiles No.107 (September 1995).

ONE DAY IN 1934, the faux “radio announcer” in Ed Wheelan's Minute Movies comic strip made a cryptic request: "If Morris Weiss is listening," he said, "let him get in touch with Ed Wheelan." Weiss missed seeing the strip, but a friend told him about it, and when he phoned Wheelan, the veteran cartoonist asked the 19-year-old freshly graduated High School of Commerce student if he'd like to do the lettering on Minute Movies. That was the beginning of Weiss's 42-year career as a cartoonist. At the time, Weiss was trying to decide between cartooning and illustrating as a career. New York's High School of Commerce was conveniently located in midtown Manhattan (where Lincoln Center is now), and Weiss took advantage of the convenience to call upon as many illustrators and cartoonists as he could—asking advice, showing his work, collecting original drawings. "I

met Charles Dana Gibson," Weiss recalled when we talked in October

1992, "and James Montgomery Flagg and all the famous comic strip

artists— Edwina Dumm, the dearest, sweetest person, who was very nice to

me, who was then doing the Sinbad page [about a mischievous little dog] for the

old Life magazine and her comic strip, Tippie and Cap Stubbs.

Gibson, a kindly gentleman, said to me, ‘I was like you once, young and

ambitious.’ Flagg wouldn't let me leave his apartment after drawing me until

an But Weiss's cartooning career was not destined to take flight from the launching pad of Wheelan's strip. "I tried hard," Weiss said, "but I couldn't master the 170 Gillot point for lettering. After a week, he let me go, and I understood why." A few weeks later, Weiss heard that Pedro "Pete" Llanuza was looking for an assistant on Joe Jinks. Having found a penpoint more congenial to his hand, Weiss became Llanuza's assistant, doing the lettering, inking the backgrounds, cleaning up the art, and delivering the strips to the syndicate office. "He paid me six dollars a week," Weiss said. "And after four months, he gave me a raise to seven dollars a week." Seeking to increase his income, Weiss applied to Harold Knerr to do the lettering on The Katzenjammer Kids. Later, he joined the Max Fleischer Studios as an opaquer, his first full-time job, leaving Joe Jinks but continuing to letter for Knerr in his spare time. Weiss's

big break came in the spring of 1936—partly as a result of a Christmas card he

produced the previous year. Designed as a promotional piece as well as a

seasonal greeting, the card showed young Weiss at his drawingboard and, pinned

to the wall behind him, his copies of the original drawings he'd received from