|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 322 (March 14, 2014). Another big bounding hare-raising ramble through comics both present and past, including the first Watterson cartoon in 18 years and reports on NCS Reuben nominees, the Doonesbury hiatus and a historic comics mural being threatened, taboos being violated in newspaper comics, and Jonah Hex being stuffed AGAIN, and reviews of the comic strip Mike Du Jour and other Mike Lester works, some graphic novels, and a half-dozen books (including Rube Goldberg, George Wunder’s Terry, Alley Oop’s time travel debut and a new “biographical dictionary” of cartoonists, complete with a digression into lore and history), and a long discussion about sins being committed in the name of “graphic novel.” Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Reuben Nominees Jen Sorensen Wins Herblock Paige Braddock Gets Alumni Award Bud Plant’s Mail Order Catalogue Langston Hughes Poem Illustrated Historic Comics Mural Threatened

Disney vs. Stan Lee Media over Spider-Man Children’s Book Illustrator Takes Over Editoon Gig Watterson’s First Published Cartoon in 18 Years

LAST DITCH OFFENSIVE College Defunded for Teaching Fun Home

Doonesbury Hiatus Mike Lester & Mike Du Jour Kerfuffle at Denver Comic Con

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Harv Cartoons Discussed

EDITOONERY Recent Editorial Cartoons Stop Do Nothing Congress’s Pay

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Luann, Pearls, Get Fuzzy; Sex and Dirty Words

Time’s Oscar Game Beatles 50th

BOOK MARQUEE Feiffer’s Kill My Mother Barnaby Fraud at Dover 50 Years of Mad’s Dave Berg Jacky’s Diary Forbidden Worlds, Volume 3: Nos.9-14 New Yorker Big Book of Cats

BOOK REVIEWS Biographical Sketches of Swann Collection Cartoonists George Wunder’s Terry and the Pirates Alley Oop 1939: First Time Travel Adventure The Art of Rube Goldberg

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Dark Rain: A New Orleans Story Marble Season SuperZelda: The Graphic Life of Zelda Fitzgerald In True Graphic Novels, Pictures Set the Pace Bohemians: A Graphic History Slayground: Richard Stark’s Parker Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story

Collectors’ Corniche George Scarbo’s Comic Zoo Ike’s Military Highways

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Bad Ass No.1 Ms. Marvel No.1 Jonah Hex Stuffed (Again)

Onward, The Spreading Punditry A Love Letter to Big Government

PASSIN’ THROUGH Bhob Steward, 1937 - 2014

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: when you get to the $ubscriber/Associate Section (perusal of which is restricted to paid subscribers), don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

AWARD SEASON It’s that time of year again: now that the movie industry’s award season has concluded with the Oscar presentations, the parade of awards for cartoonists begins with the nominees for the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben for the “cartoonist of the year.” This year, NCS named four finalists, not just three, the usual number. And all four are, as is usual with the Society, syndicated newspaper cartoonists: Hilary Price, Rhymes With Orange; Wiley Miller, Non Sequitur; Stephan Pastis, Pearls Before Swine; and Mark Tatulli, Lio and Heart of the City. “I was expecting that about as much as I was expecting to get called up to go play in the NHL,” Price told Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs. “It was a really, really nice surprise.” Said Miller: “The initial reactions were the obvious ones of surprise followed by delight. It really did seem to come out of the blue for me, completely unexpected.” This is the sixth Reuben nomination for Pastis; the other three are first-time finalists. “I am so pleased to be standing shoulder to shoulder with those three,” Price told Cavna. “Or, I guess, Stephan and Wiley are standing shoulder to shoulder, and Mark and I are standing at about nipple height to them.” “The best part came when I learned who the other candidates are, four in all this year, which is unusual,” Miller said. “All the others … are very good friends of mine, and I honestly couldn’t be more pleased. I know this sounds like the usual ‘aw shucks’ [baloney], but I’m genuinely happy to be a part of this group, and will be very happy regardless of who takes home the trophy. I really think that we’ve already won in being nominated. The trophy will just be icing on the cake.” The winner will be announced May 24 at the NCS Reuben Awards dinner in San Diego. If she wins, Price will be only the second woman to collect the Reuben statuette; Lynn Johnston of For Better or For Worse was the first in 1985. (And she declined her nomination in subsequent years, saying no one should get the Reuben more than once; a position the Society adopted formally a few years later.) Price would also be the only openly gay winner. In its prolonged Reubenesque glorification of syndicated comic strip cartoonists—only 18 of the 67 winners have not been syndicated—NCS continues to overlook such stellar figures in cartooning history as Gahan Wilson. And only 5 editorial cartoonists have ever got the nod.

Herblock Prize. The eleventh Herblock Prize for excellence in editorial cartooning was awarded to Jen Sorensen, the first woman to win. “Winning the Herblock is one of the finest moments in a political cartoonist’s life,” Sorensen told the Washington Post. “Being the first woman to win the prize makes it an extra-special thrill.” Sorensen, a former Charlottesville alt-weekly cartoonist who now draws for the Austin Chronicle, was a Herblock finalist in 2012 according to Michael Cavna at his ComicRiffs blog. That year, she told Cavna: “It’s so nice to see our genre of political cartooning acknowledged after so many years in the wilderness.” In announcing the winner, the judges issued a statement about Sorensen: “Her strong portfolio addresses issues that were important to Herblock, such as gun control, racism, income inequality, healthcare and sexism. Her style allows her to incorporate information which backs up the arguments she presents. Her art is engaging and her humor is sharp and on target.” The Herblock Prize consists of a silver Tiffany trophy and $15,000 after-tax cash award. Sorensen is the fourth editoonist to win who is not a full-time staffer on a major daily print newspaper, joining Tom Tomorrow and Matt Bors (the first of the three alternative publication cartoonists to win) and Matt Wuerker, who’s gig is Politico, initially a mostly online newspaper. The seeming flood of alties may be explained in part by the presence on each year’s panel of judges of the previous year’s winner. In addition to Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins), this years judges included editoonist Tony Auth and Sara Duke of the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. But Sorensen stands amply qualified before any panel of judges. In addition to receiving several Alternative Newsweekly awards, last year she won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award and the National Cartoonist Society’s Award for Best Editorial cartoonist. Cavna reports on her career—: Raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Sorensen attended the University of Virginia, where she drew a daily comic strip, Li'l Gus, for the campus newspaper, University Journal, from 1994 to 1995, and contributred to the satirical magazine The Yellow Journal. Sorensen was soon published in various comic anthologies, including Action Girl and the Big Book of the 70's. She published her own magazine, Slowpoke Comix No.1, in 1998. In 1999, one year after the book’s publication, Slowpoke became a weekly comic strip. As of 2012, Cavna said, the strip goes simply by her own name, though a few alternative weekly papers continue to use the Slowpoke name. Sorensen

has published three volumes of cartoons: Slowpoke: Café Pompous from

2001, Slowpoke: America Gone Bonkers from 2004 and her latest book, Slowpoke:

One Nation Oh My God! published in 2008. Besides her weekly political cartoon,

she has Sorensen has written and illustrated a number of long-form comics, most notably a piece on health care reform commissioned by Kaiser Health News, and a synopsis of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice for NPR. She also writes a political weblog on her site. Here are four of her recent cartoons.

AND WHILE WE’RE TOTING UP AWARDS, here’s the University of Tennessee giving one of its alums, Paige Braddock, its Accomplished Alumni Award, conferred upon notable alumni for their success and distinction within their fields. Braddock is executive vice president and creative director of the Charles Schultz Studio. Schulz met Braddock at comics conventions and, impressed with her work and philosophy, hired her to work with him at his studio in Santa Rosa, California. At Schulz’s death, Braddock was selected to take his place as head of the creative arm of the Studio. The UT press release reports: “Braddock and her team are responsible for the worldwide production and quality control of the Peanuts and Snoopy brands. The enterprise is global, with more than half its sales revenue coming from outside the U.S.” Braddock

also produces Jane’s World, a comic strip about a young lesbian living

in a trailer with her roommate, Ethan. Wikipedia reports that Braddock created Jane's

World so that women, particularly lesbians, would have a comic strip

character that they could relate to, though it's meant to be accessible to a

wider audience of many genders. Braddock devised Jane’s World in 1991

but it wasn’t until March 25, 1998 that the strip appeared on the Web. In 2001

United Media's Comics.com website picked up reprints of These days, we can find the strip online at GoComics.com, where Jane has just learned that her mother knows she’s gay. In addition to web and newspaper publication, Braddock publishes the strip in a comic book format through her own publication house, Girl Twirl Comics. The trade paperback versions feature covers created by different artists.

SHORT STOPS Bud Plant, who shed his mail order business a year or so ago to rely completely upon online ordering, is back with a printed catalog issued through the Postal Service. Presumably you could request to be put on the mailing list: BudsArtBooks.com or 800/2421-6642. NPR Books and Code Switch finished Black History Month by asking three comic artists to illustrate something — a person, a poem, a play, a book, a song — that inspired them. Afua Richardson, an award-winning illustrator who's worked for Image, Marvel and DC Comics, chose Langston Hughes' great poem "The Negro Speaks of Rivers." And you can see the results at npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2014/02/24/280166355/blood-and-water-illustrating-langston-hughes-rivers . Much as I admire the art, poems cannot be illustrated. Poetry is essentially a specimen of word play. Illustrations may be inspired by poems, but they cannot, by definition, represent them. And if they try, they inevitably fall short, robbing the words of the suggestive power they have when standing alone, unaided.

HISTORIC COMICS MURAL THREATENED A New York watering hole called Costello’s was once a storied hangout for various cartoonists and writers of The New Yorker persuasion. But mostly writers. Walt Kelly frequented the place—rather than the Palm, a former speakeasy on Second Avenue the walls of which are decorated with famous cartoon characters, drawn there by their originators. The Palm was for cartoonists; Costello’s was for writers, and Kelly saw himself as chiefly a writer. So did James Thurber, another Costello’s habitue. Kelly never drew on the wall, but Thurber did. The story is that Thurber drew his pictures on the wall of the original Costello’s, another speakeasy that opened under the Third Avenue El in 1929, to settle his bar tab during the Depression. I had lunch at Costello’s once; Milton Caniff took me there while I was in New York interviewing him for The Biography (see Meanwhile description elsewhere on this site). We sat at a table for two, and nearby there were a couple framed Thurber drawings—on plaster. Caniff explained that this Costello’s (on East 44th Street) was not the original Third Avenue Costello’s, which had closed some years before but reopened at the present location. Knowing that they had an art treasure on the wall in Thurber’s scrawls, the management had the decorated sections of the wall at the old place cut out and bodily removed and framed so they could hang them in the new Costello’s, which was now operated by the son of the founder. Eager to establish the place’s reputation as an art gallery of original cartoon murals to rival the Palm’s, Tim Costello invited several notable cartoonists to draw their characters on the wall in the dining room beyond the bar in front. The deal, engineered by New York Daily News’s legendary sports cartoonist Bill Gallo, was that if Costello closed the place for 24 hours and offered free drinks and food, Gallo would get “the best known cartoonists in the country to paint the wall.” And so it transpired. Caniff drew Steve Canyon. Others drew their characters— Bill Holman (Smokey Stover), Bill Keane (The Family Circus), Paul Fung (Dumb Dora), Bill Kresse (Super Duper) and others of the freelance fraternity— Al Jaffee, f’instance; even Stan Lee. And so on. A couple months ago, the wall was described by the New York Daily News’ Brian Kates: “In the center, with a nicotine patina, is Gallo’s Basement Bertha, brandishing a membership card in the National Society of Cartoonists. Stretched across the top, from the hand of Mad magazine’s Sergio Aragones, is a small army of Mexican banditos, tipping their sombreros to a buxom senorita. At the bottom is a caricature of bartender Fred Percudani, smoking a stogie and riding a bike with two flat tires. In between are what Jan Ramierz, museum director of the New York Historical Society, called ‘a wonderful, wonderful vignette of New York and the world of cartooning.’” Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey is among those pictured on the wall. “I did my part,” Walker explained, “—climbed up a ladder and drew my character. Then I got down and had some drinks, so I don’t remember too much after that. But Costello’s was a wonderful old place.” The emphasis is on was. Several years after the muralizing, Costello’s closed. But the place re-opened as the Turtle Bay Café. The owner of Turtle Bay Café lost the lease recently, and the joint is going to be torn down to make room for “a trendy eatery.” What will happen to the wall mural was, at the time Kates wrote (end of January), unknown. The Thurber drawings had already disappeared long ago, their whereabouts unknown. Said Kates: “The Historical Society is one of several institutions that hope to find a way to preserve the wall for posterity. But removing an old 20x4-foot plaster wall without destroying it requires considerable finesse and potentially a lot of money. And then there’s the problem of what to do with it once it is removed.” None of these problems have yet been solved as far as I know.

NON-ENTITY SUES DISNEY FOR RIGHTS TO SPIDER-MAN The legal machinations of Stan Lee Media Inc.’s claim to own Spider-Man continue apace. Eriq Gardner at hollywoodreporter.com says: “Predicting a conclusion to SLMI’s drawn-out battle over Spider-Man rights is somewhat of a fool's errand because every time the seemingly down-and-out company gets punched in the stomach by a judge, it figures out a new way to stand up in court again.” Gardner continues: “Last September, Disney filed a lawsuit in Pennsylvania court against a musical production entitled Broadway: Now & Forever, which included scenes or references from The Producers, Billy Elliot, Wicked, Jersey Boys, Mary Poppins, The Lion King and yes, Spider-Man: Turn off the Dark. American Music Theatre was the defendant, and after being sued, it struck a licensing agreement with SLMI for Spider-Man rights. ... Now there's discussion over whether SLMI is precluded by prior court decisions from asserting rights over Spider-Man. One of the big reasons that SLMI keeps losing is that judges keep deciding that the matter has already been determined by past judges. But SLMI believes that no judge has ever gotten to the merits of its claims of ownership over Stan Lee's creations.” Recently, in continuing the fight, Disney gave a Pennsylvania judge two more big reasons why SLMI's claims should be disallowed once and for all. First, “Disney says SLMI's claims are time-barred. Its subsidiary Marvel and licensees ‘have continuously and notoriously used the Marvel Characters for more than fifty years,’ says Disney, adding that SLMI knew about this and could have objected when it made a deal with Stan Lee in 1998. “Second, Disney says that SLMI is an ‘administratively dissolved corporation that lacks the capacity to license.’ [SLMI is the outfit whose CEO turned out to be a conman of international reach, who subsequently absconded to Australia or some other planet; Stan Lee had long terminated any connection with the operation.—RCH] Essentially, Disney says SLMI has ceased to function but for litigating since 2002. And Disney adds that under Colorado law, a dissolved corporation can't carry on its business except to ‘wind up and liquidate its business and affairs.’ “If the Pennsylvania judge accepts the arguments,” Gardner concludes, “it would seemingly be game over for SLMI. But we'd be a fool to say it'll really mean, The End.”

EDITOONS IN OGDEN, UTAH TO LOSE BITE From Alan Gardner whose DailyCartonist originates in Utah: I’m a bit surly this morning after reading the news that my one-time local paper the Standard Examiner hired a freelance cartoonist to do local cartoons once drawn by the genius cartoonist (and personal friend) Cal Grondahl. The Examiner laid Cal off last month a couple years shy of his retirement [reported in Opus 320]. Now I learn the paper has hired a children’s illustrator, Val Chadwick Bagley (not related to the award-winning Salt Lake Tribune editorial cartoonist Pat Bagley), most noted for his work for The Friend and New Era – children and teen magazines for the Mormon church. Being a decades long contributor to various church publications guarantees Val won’t be touching any issues related to the church’s heavy influence in local politics and culture. In other words, they didn’t hire an editorial cartoonist with any bite, they hired an illustrator who’s pen will stay holstered on a lotof important issues that will affect their readers. RCH: One of the traditional (and disdained) roles of editorial cartoonists in the ancient history of newspaper journalism was to illustrate a paper’s verbal editorials, giving the management’s opinions a visual-verbal double whammy. But modern editoonists eschew such mindless errands.

NEW UNEXPECTED WATTERSON ART As far as we know, the reclusive Bill Watterson, in hiding since abandoning his insanely popular comic strip Calvin and Hobbes 18 years ago, hasn’t drawn a cartoon since. Until just this month, when he drew a cartoon for the poster about “Stripped,” the documentary that web cartoonist Dave Kellett has co-directed about the changing (perhaps disappearing) newspaper comic strip world. The documentary, which is now available on iTunes and will be offered in DVD starting April 2, contains interviews with a score or more cartoonists, including the creators of Garfield, Cathy and Beetle Bailey, who talk about their craft and how it is changing as newspapers have begun to go away. Watterson is also interviewed in the film, but not on camera. As a disembodied voice, he says: "In the right hands, a comic strip attains a beauty and an elegance that really I would put against any other art.” Kellett, his chutzpah amped by this success with Watterson, was emboldened enough to ask Watterson if he would draw a picture to promote the film. Apparently, said Kellett’s co-director Fred Schroeder to the New York Times, “Watterson really wanted to express some thoughts about comics and cartooning.” Said Watterson: “Aside from supplying a few sentences to the documentary, I’m not involved with the film, so Dave’s request to draw the poster came completely out of the blue. It sounded like fun, and maybe something people wouldn’t expect, so I decided to give it a try.” He explained the cartoon’s genesis to the Washington Post: "Given the movie's title and the fact that there are few things funnier than human nudity, the idea popped into my head largely intact," he said. "The film is a big valentine to comics, so I tried to do something really cartoon-y. I had thought of having it colored with off-registered printing dots like newspaper comics, but Dave asked if I'd paint it instead, and I think he made the right call." At the New York Times, he continued: “It’s a silly picture that sums up my reaction to the current publishing upheaval, so I had a good time, and I hope it brings the film some attention.” To

resort to understatement—it undoubtedly will. Gazing fondly at the cartoon, it’s satisfying to notice that Watterson has lost none of his aptitude for comedic visuals. Not that it’s a surprise: if you draw every day for ten years, as he did while producing Calvin and Hobbes, you acquire a certain skill that does not erode over the years, even if you aren’t drawing every day anymore. And speaking of Watterson’s persistent cartooning expertise, here’s the original Watterson self-caricature erstwhile on the wall at Universal Press HQ, the picture that inspired the one I posted lately with the Watterson speeches in the Harv’s Hindsight.

More Unexpected Watterson. Alan Gardner reports that some early Bill Watterson art has surfaced—cartoons he drew for his high school newspaper in 1973-74. The drawings are posted at DailyCartoonist.com for February 17. It’s a comfort to see this juvenilia: they reveal that, like almost all artists in their raw youth, he drew pretty badly before he got really good.

LAST DITCH OFFENSIVE In South Carolina in mid-February, the House Ways and Means committee voted 13-10 to cut the College of Charleston’s budget by $52,000, the amount the school spent last summer on The College Reads!, an annual campus-wide initiative designed to promote discussion of “challenging” books among faculty, staff and students. Kevin Melrose at robot6.comicbook resources.com reported that problem was the choice of Alison Bechdel’s gay-themed graphic novel Fun Home, which “drew fire in July from a conservative Christian group that labeled the graphic novel ‘pornographic.’” At the same time, lawmakers cut $17,000 from the budget of the University of South Carolina Upstate for assigning "Out Loud: The Best of Rainbow Radio” which is about South Carolina’s first gay and lesbian radio show. The legislative drive, reported Carolyn Kellogg at latimes.com, was led by State Representative Garry Smith, a Greenville Republicon who sits on the House’s higher education budget committee that approved the cuts, who “pushed punishing the College of Charleston and USC Upstate for their book choices." Said Smith: “One of the things I learned over the years is that if you want to make a point, you have to make it hurt. I understand academic freedom, but this is not academic freedom .... This was about promoting one side with no academic debate involved.” As I gather from the purported purpose of the program at Charleston, the whole idea was to foster discussion and, yes, debate. But Smith and his ilk, looking at the world through the isinglass in their navels, can’t see that. Of course.** College of Charleston professor Christopher Korey, who leads the college's First-Year Experience, which oversees the summer reading program that included Bechdel's book, said: "The [school] committee recognized the book might be controversial for a few readers, but the book asks important questions about family, identity, and the transition to adulthood. These are important questions for all college students." Important to confront and discuss—and debate. Smith told the Post and Courier that Bechdel's book "goes beyond the pale of academic debate," because "[i]t graphically shows lesbian acts," adding (of course) that the college was "promoting the gay and lesbian lifestyle." As attitudes across the nation change in support of such things as same-sex marriage, people like Smith are increasingly fighting a rear-guard action in retreat away from an inevitable defeat. Desperate to avoid facing the inevitable, they pick on whoever seems vulnerable. In a statement released by her publisher Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Bechdel said: "I'm very grateful to the people who taught my book at the College of Charleston. It was brave of them to do that given the conservative pressures they're apparently under." She continued, "I made a visit to the school last fall for which they also took some flak, but to their great credit they didn't back down. It's sad and absurd that the College of Charleston is facing a funding cut for teaching my book—a book which is after all about the toll that this sort of small-mindedness takes on people's lives." The funding cuts approved by the budget committee will go to the House floor for debate on March 11.

**Looking at the world through the isinglass in their navels is a cute way of saying their heads are so far up their collective ass that the only way they can see anything is through a window in their navel.

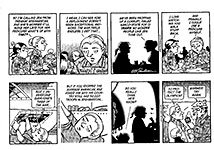

DOONESBURY’S HIATUS AND THE FATE DU JOUR Poached from the redoubtable Michael Cavna’s at his ComicRiffs blog at the Washington Post: Starting February 24, Garry Trudeau put the daily releases of his Pulitzer Prize-winning Doonesbury on long-term hiatus in order to concentrate on writing his political satire live-action tv show, “Alpha House,” which recently ended its debut season with such strong viewership that Amazon Studios has picked it up a second season. Trudeau will continue to create new Sunday Doonesbury strips; the rest of the week, readers will get reruns dating back to the feature’s syndication launch in 1970. More than 13,000 potential “Flashback” strips, Universal Uclick notes, haven’t been seen in a newspaper since their initial run. And that’s a lot of inventory to pick “Flashbacks” from. Trudeau intends to return full-time to the strip eventually, but he admits no one can say for sure in these days of “lateral movement” by creators in the media and arts. Said he: “I’ve always thought of myself as a comic-strip lifer, which is common in our industry and an annoyance to younger cartoonists. I love working for newspapers, and can't imagine life without them. Which is why I'm keeping one foot in with the Sundays.” “Comic strips and episodic tv actually draw from similar skill sets,” Trudeau told Cavna. “I’m accustomed to writing dialogue, constructing scenes and developing characters. And, of course, I think visually.” But “Alpha House” does present the left-leaning Trudeau with a challenge: his protagonists are a quartet of conservative senators (played by John Goodman, Clark Johnson, Matt Malloy and Mark Consuelos) who room together while in Washington, and Trudeau is on more familiar ground depicting the four as they fend off Tea Party challengers, ethics probes and blasts in Afghanistan. Cavna asked the cartoonist whether it was difficult to leave one of his creations behind in order to tend to the other. “They're both full-time jobs,” Trudeau said, “—so I had to choose, and no, it wasn't that difficult. I've done the strip for 43 years — 45 if you include the college edition [at Yale] — and I'm ready for an extended break. A hiatus comes with uncertainty, of course: I can't assume I'll be welcomed back a year or two from now. The comics page is zero-sum real estate, and there are a lot of interesting new strips that editors could turn to while I'm away.” Asked about the differences between the two enterprises, Trudeau said: “The goal is essentially the same: to entertain. Sure, commentary is part of the package, but if you can't clear the comedy bar, you don't have a show. The main difference is that the strip allows me to be a little emperor, in total control of every element. On a tv show, by contrast, I have to get buy-in from 120 teammates. ‘Alpha House’ is a small corporation, and when you consider all the disciplines, talents and temperaments involved, it's amazing that the show looks anything like what I imagined it would be. And yet, miraculously, it does.” I don’t doubt that Trudeau intends to return to doing Doonesbury seven days a week instead of just on Sundays. But the temptations of the other medium are clearly great, and the last time the cartoonist took a sabbatical—in 1983-84—he announced that he’d be gone for 18 months but stayed away for almost two years. And he’s now 65, which, for many of us, is retirement age. Despite his undeniable affection for the comic strip medium, this time, he may call it a career after a few seasons of “Alpha House” and a couple years of Sunday Doonesburys. The

Sunday Doonesbury is stand-alone satire, and I’m glad Trudeau is

continuing to do it. But the real wallop of the strip is achieved cumulatively

in the gradual pile-up of edgy commentary day-by-day. At your eye’s elbow are a

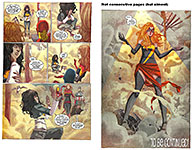

couple consecutive strips from earlier this year; this is the kind of satiric

comedy we’ll miss in the non-continuous Sundays. And Trudeau, as usual, is right in these strips. Here’s Ernesto Londono at the Washington Post on March 6: “These days, 12 years after the start of America’s longest war, far fewer U.S. troops are being killed or wounded in Afghanistan, but the war churns out American casualties by the dozen each week. Their injuries rarely make headlines.” “By the dozen.” Londono goes on to quote Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., a former Air Force pilot, after returning from a visit to Kabul a few weeks before the State of the Union speech: “I think there is a sense in the military that Americans are not paying attention anymore. I think they’re right, to be honest. There is a sense that it’s over, but it’s not.” Exactly the proposition advanced in these Doonesbury strips. And if, without the daily dose, Doonesbury loses its sting, will it also lose its readers? Among whom number some 1,400 newspaper feature editors. While Trudeau is juggling conservative senators on tv and a cast of thousands of liberals in the comic strip, other cartoonists lurk, ready to pounce on any vacancy that shows up on the daily newspaper turf. And the pouncing has already begun as newspaper editors ponder what to do about Doonesbury in rerun.

AT THE STAR-TELEGRAM in Fort Worth editor Jim Witt mused: “It’s hard to know what to say when an old friend tells you he’s leaving, maybe never to return. That’s what’s happening to the Star-Telegram beginning Monday, February 24, when the Doonesbury comic strip that runs daily on our opinion pages goes away. The syndicate offered to sell us old Doonesbury strips that have already run daily,” Witt continued, “but because the cartoon depends so much on topical humor we declined. Strips about Nixon during the Watergate years just don’t have the same punch now that they had back in the day.” Witt goes on, sounding more and more like he’s decided Doonesbury may never return. “The Star-Telegram has been running Doonesbury since October 26, 1970. We were one of only 28 newspapers that picked up the strip from Day One. It now runs in more than 1,400 papers worldwide. Most of the other strips we ran when Doonesbury debuted have been discontinued for a long time. They include Little Orphan Annie, Mandrake the Magician, Animal Crackers, Half Hitch, Lolly, Rip Kirby, Rick O’Shay, Redeye and The Smith Family.” At the Knoxville News Sentinel, Jack McElroy puts the question bluntly: “Has Doonesbury’s time passed? That’s a question the News Sentinel’s Editorial Board will be contemplating this week. ... This past week, emails were bouncing among Scripps editors asking for ideas on what to do next. Some are considering other politically oriented comic strips, such as Candorville by Darrin Bell or Prickly City by Scott Stantis. Others will stick with the reruns and see if Trudeau returns to full-time work this fall. I’m open to suggestions,” McElroy finishes. “Doonesbury has been a great comic for more than 40 years. But if Trudeau is moving on, is it time for this paper to do likewise?”

AT THE ARIZONA STAR, Doonesbury dailies no longer appear. In their place, Mike Lester’s Mike Du Jour. As an indication of the caliber of Lester’s strip, it was the only strip launched into national syndication in 2012. You can find this historic moment detailed at Opus 296, but we’ll add a little to its legend here. In his other guise, Lester is an excellent editorial cartoonist of the conservative persuasion. Or so it seems to me. He denies it. “I find it odd,” he told me a few years ago when we first met, “that I’m referred to as a conservative. Somewhere in the Constitution, it plainly states: all men should be made fun of equally.” But don’t take his word for it. Or mine. In the immediate vicinity, I’ve posted some of my favorites of the Lester oeuvre —over the GeeDubya years mostly, with a couple of the most recent. You look ’em over and decide: conservative or crank?

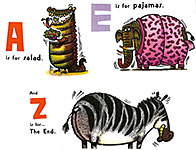

Incidently, one of the cartoons commemorates the deaths of Ronald Reagan and Ray Charles, who, I’d forgotten, died within a week of each other: June 5 and June 10, 2004 respectively. Otherwise—the guy with the virgin daiquiri always makes me laugh out loud; ditto the guy being tortured in the “newly remodeled interrogation room.” Lester’s caricatures of Michael Moore and God are a hoot. And his depiction of the emerging “civil discourse 2004" is about as bipartisan as you can get. The two most recent cartoons go after Obama pretty good, and while I think the “affordable sex act” cartoon is hilarious (particularly the woman gaping at the poster or flyer or whatever it is), I’m not sure I can explain it. Despite Lester’s misguided convictions, I love his cartoons. Ditto Mike Du Jour —perhaps even more because Lester’s political ideology doesn’t seem on display so blatantly. So it’s not as if the Star is replacing the liberal Doonesbury with the conservative Mike. (Arizona and its reputation as a right-wing nut orchard notwithstanding, the only two operating editorial cartoonists in the state, Steve Benson at the Arizona Republic and David Fitzsimmons at the Star, are both more liberal than nutty.) A native of Georgia, Lester lives in Jacksonville, Florida, where he moved with his wife Regan last July (her sister and brother-in-law live in Jacksonville). He left a full-time gig as editorial cartoonist with the Rome (Georgia) News-Tribune. The paper filed Chapter 11 in January 2012, and Lester was a casualty of the ensuing re-jiggering of the balance sheet. Until Lester’s departure, the paper was the smallest circulation daily newspaper in the nation with a full-time staff editoonist. No longer true; Lester was not, to my knowledge, replaced. “Great people to work for, but it was time to move on,” Lester said. “So we did.” David Crumpler at the Florida Times-Union, another paper where Mike Du Jour began last month, supplies more Lester background (in italics): Lester, 58, grew up in Atlanta and was an art major at the University of Georgia. He got his start in newspapers doing illustrations for the Atlanta Journal and Constitution. He also began doing freelance work for ad companies and corporations, something he continues to do today. In Lester’s words, “I’m always on deadline.” He’s not complaining. He always liked to draw, he said, and figured out well before college that this was probably how he was going to make his living. Mike Du Jour got its start during the dot.com bubble in the 1990s. The Wall Street Journal contacted Lester and asked if he could do an animated comic for the paper’s website. “I didn’t know the first thing about animation,” he said. “At that point, I didn’t even know much about websites. So of course I said ‘yes.’” He wrote and drew a 30-second animated web cartoon that appeared five days a week. “But as the dot.com bubble languished, Mike Du Jour went on lengthy hiatus.” [Lester told me that he had compiled a wad of gags for the show and when it expired, he thought about re-purposing them for print. The first title for this cache of gags was “What the?”—RCH] Under the title Mike du Jour, the strip was picked up for syndication in 2012. Lester also spent close to a decade doing illustrations for children’s books. The first, A Is For Salad, which he wrote as well as illustrated, made the New York Times list of Top 10 Children’s Books of 2002. By 2009, he’d done the illustrations for seven more.

LET ME INTERRUPT Crumpler here to point out a couple of things, one of which should, by now, be obvious: Mike Lester and I are friendly acquaintances, both members of the National Cartoonists Society and of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, and when we run into each other at the annual shindigs of these outfits, we enjoy each other’s company long enough get just one more drink. I refer to him as “Lester” in this article in order to distinguish him from the protagonist of his comic strip, whose name is Mike. I’d just as soon call Lester “Mike,” but doing so would presumably betray my acquaintance with him and thereby severely unhorse my supposed objectivity in commenting on the caliber of his work—even though it was my admiration of his work that first prompted me to make his acquaintance. The second of the pointy things I’ve interrupted Crumpler to say is that Lester has won the NCS Reuben Division Award for Best Book Illustration four times since beginning to dabble in the genre—in 2000, 2006, 2008 and 2010. The photo of Lester and me that you can see out of the corner of your eye was taken at the 2007 Reuben Banquet where he was up for what became his second win. The peculiar guilt-ridden expression on my face is caused by my realization that I was being photographed while seemingly accepting the ten dollar bill Mike was slipping into my hand to persuade me to vote for his entry. He should have known better than to think I could be bribed for anything less than a twenty. But he won anyway.

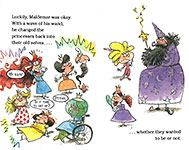

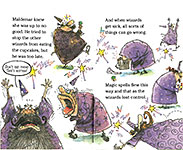

Next to the incriminating photo are Lester pix from two of his children’s books. The first is from the aforementioned A Is For Salad, a cruel perverse joke on the young because, as any fool can tell (I can tell), “salad” does not begin with an “A” but the creature consuming the salad, an alligator, does begin with an “A.” Perhaps Lester wants children to learn that things are not always what they claim to be. “E” is really for “elephant,” isn’t it? And I’m sure any parent reading this book to, say, a six-year old child would be corrected at every step by the child, which brand of human is always more perceptive than the adult version. I like especially that “Z” is for “the end”—the end in question being not only the end of the book but, apparently, the south end of a zebra going north. How Mike came up with this style of drawing is another story, I’m sure; but the visuals—all the animals winking at us in order to let us know they’re in on the joke—seems perfectly appropriate for the subject. And for the presumed audience (parent with offspring attending). The other two illustrations are from a book Mike only illustrated—The Really Rotten Princess and the Cupcake Catastrophe written (it sez here) by “Lady Cecily Snodgrass.” (I’ve put quotation marks around the name because Lady Cecily is almost certainly someone’s nom de plume; the coupling of an aristocratic title, “Lady,” with the wholly pedestrian last name, “Snodgrass,” gives it away as a fabrication.) To appreciate Mike’s artwork, you don’t need to know much more than that the Rotten Princess has made cupcakes that taste awful. Maldemar is the court wizard. (“Mal de mer” being French for sea sickness; but I suppose you don’t need to know that.) I like the drawings so much I bought a copy of the book for myself so I could periodically take it off the shelf to admire the loose pencil lines and manic textures. I’ll let you alone to do the same while I rejoin Crumpler for his article on Lester and his new comic strip, Mike Du Jour, in progress.

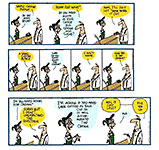

DRAWING CHILDREN’S BOOKS, Crumpler quotes Lester as saying, never proved as satisfying as drawing cartoons. [So Lester persisted in drawing cartoons all the time he was also dabbling in children’s literature.] The name “Mike Du Jour,” Lester said, is a “triple entendre.” It’s the main character’s name, the cartoonist’s name and “an honest description of the strip” — as in, a reflection of whatever fresh ideas are brewing in Lester’s mind. “The nebulous title doesn’t paint me into a corner.” He sees Mike as autobiographical, he said, “not in the sense that it’s about me, but ‘This is what I am thinking.’ ” He has described his protagonist, Mike, who is single, something of a loner, who works for a generic company called Big Bottom Line Inc., as both “an observer and victim of his life.” The humor in Mike Du Jour is observational rather than topical, Lester said, although topical events — such as the Winter Olympics — may inspire a series of drawings now and then. He develops a weekly theme for his daily strips. [“Hit Man Week,” he explained to me, “—Emperor w/no Clothes Week, Lint Week, so it’s essentially a weekly serial. What you read on Monday, you’ll read through the week. Sundays stand alone. The result is that I really don’t develop characters, including Mike, in the common way. They show up when the situation calls for them, and some of them have stuck around—like the Key Cat Lady, Emperor and a composite of every barista, waiter and waitress I’ve ever met.—RCH, interrupting again.] Basically, “It’s just kind of a smart-aleck cartoon,” he told Crumpler. “Humor is still what it always was. Funny is funny.” Lester may make it sound simple, but his observation that a good joke “has to have an element of surprise” gives you a sense of the work a single strip may involve. [And

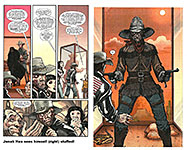

(interrupting yet some more) we can easily see the element of surprise at work

in the accompanying array of strips in which Mike, relaxing at his favorite

saloon, encounters a man dressed as a woman. Reflecting on the last two strips

in the series, it may seem the jokes are predictable, but Lester carefully

staged them to insure the surprise.—RCH] “It’s all about the setup, so that you don’t see the punch line coming,” Lester said, and you don’t know what’s going to happen until the last panel. [But you should have known. In fact, the realization that dawns as you chuckle over the joke is that the thing turned out as could be anticipated—and should have been; and that’s an essential part of the comedy, the groaner part.—RCH, still interrupting.] “It’s a blessing to be able to do this,” Lester said. “It’s a gift. I don’t take it for granted at all.” He has three editors at The Washington Post Writers Group, and though Mike Du Jour is “not written by committee,” he thrives on the collaborative process. But his first editor, he said, is his wife, and he welcomes her input. “I think I’m funny, that I can be funny,” Lester said. “But I’m the second funniest person in the house.” [RCH, back full time:] And who am I to contradict Mike? But I don’t think Regan can draw, and it’s Lester’s weedy drawing style that enhances the comedy in his strip with the spindly hilarities of his line constantly in search of itself. The Star’s Gerald Gay asked Lester where the idea for Mike Du Jour came from. “This is sort of my second act,” the cartoonist said. “I’ve been an illustrator for ad agencies and publishers for years. Then I got into children’s books. I’ve written enough to where I think I can call myself an author. Mike du Jour allowed me to combine all of the useless talents that alone didn’t really add up to much.” He continued: “When I embarked on this, I said, ‘We are going to be a comic strip for people who don’t think they like comic strips.’ We are just trying to be funny. There is not a running gag. My readers are smart. I don’t want to ever forget that. I am trying to make both of us laugh. If I don’t think it is funny, you aren’t going to think it is funny.” Is it a challenge coming up with ideas every day, Gay asked. “It is like having a litter of puppies every week,” Lester said. “You have to give birth to them all and keep them going. Then you start all over again. I am blessed that I get to do something that I love and that people are generous enough to publish it. I take very seriously signing my name at the end of the day. Not everybody gets to do that.” Another time, Lester, saying he loved the job, also described writing a daily comic strip is like being married to a nymphomaniac: “The first two weeks are great.” Said Gay: “You are known for your conservative editorial cartoons. Why keep politics out of Mike du Jour?”

And here, one more dose of Lester laugh-inducement, three strips regaling us with Mike’s adventures with one of those annoyingly cheerful and forever imperturbable barista persons.

KERFUFFLE IN THE MILE HIGH CITY As the Denver Comic Con approaches its third incarnation June 13-15, a kerfuffle has emerged. One of the co-founders of DCC and of the Con’s sponsor, the non-profit Comic Book Classroom, Charlie La Greca, posted a letter online that alleges (1) that CBC is not using the proceeds from last year’s roaringly successful Con to extend its program in the schools teaching literacy and art skills through comic books and (2) that some $300,000 in revenue from the Con remains “unaccounted for.” La Greca claimed that he was ousted by the organization’s board without any explanation and that no Comic Book Classroom courses have been created or taught since last year’s convention and no new programs initiated. CBC officials immediately refuted the allegations, posting a preliminary financial summary that shows the disposition of its $1.3 million 2013 revenue, and offered some explanation for La Greca’s behavior. Last year, La Greca resigned from the boards of both entities in order to take a $10,000 contract for design work for the Con. His resignation was voluntary but essential if he wanted the fee: board policies prohibit members from accepting payment; all board positions are voluntary. After the Con, however, La Greca’s contract was not renewed. La Greca presumably objected, and he and CBC/DCC entered into mediation to resolve the issue. His online outburst was, I suspect—with nothing but ordinary reasoning to substantiate—an act of frustration that mediation wasn’t working as quickly as he’d hoped. In its online response to La Greca, CBC reported that a CBC class is currently in session in a school near Denver and that numerous plans are underway to expand the reach of the program, citing at least three by name and purpose. Meanwhile, La Greca called a “town-hall style” meeting for Sunday, February 23 to air the issue, but the meeting was cancelled two hours before it was to begin because La Greca and the CBC/DCC officials had agreed to resume mediation to resolve their differences. The Denver Post, which had conspicuously promulgated the news of the disputation, failed to report the subsequent events. So I wrote an irate letter to the editor; to wit (in italics)—: A week or so ago, you ran a story in which one of the Denver Comic Con co-founders accused the sponsoring Comic Book Classroom people of various kinds of malfeasance. The article included notice of a “town-hall style” meeting on Sunday, February 23. If you had a reporter assigned to the story, you would know that the meeting was cancelled because the disputants agreed to re-enter a mediation process that had been derailed by the dispute. You didn’t run a story about the cancelled meeting or the resumption of mediation. I understand why: newspapers always prefer sensational news to reconciliation news : the former is exciting and sells papers (but how many papers are you selling at corner newsstands these days?); the latter is boring and sells nothing. Interested persons had to find out about the resumption of mediation at the DCC Facebook page. And so your journalistic nonchalance about the story has the effect of undermining print journalism: ironically, the news was on the Internet, not in the paper. Maybe the online Post carried the story; if so, it merely reinforces my point: in forfeiting journalistic responsibility in print, you give yet another boost to the medium that is slowly killing print newspapers. Postscript: No reply, of course.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS On Black History Month by Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr.: We may be “a nation within a nation,” as the 19thcentury Black abolitionist Martin Delaney declared, but, from slavery to freedom, our 500-year [African American] story is indivisible from that of the nation. And to leave it out on any given day (or to carve it out for “special display on only 28 or 29 days in February) is to distort our common past while robbing those who will shape the future of an expansive archive of resiliency and hope.”

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures From the Perpendicular Pronoun Press Archive FINAL FLING

PORTFOLIO (circa 1980). Our sub-subtitle here refers to that period in my

paisley not-to-say checkered career when I last drew cartoons for money: from

about 1978 until about 1982, I freelanced single-panel gag cartoons to

magazines by mail. I did pretty well at it, selling well over 50 percent of the

cartoons I sent out, a percentage I achieved after winnowing out a whole

category of market. At first I sent cartoons to both men’s magazines and to

“general interest” magazines, but when I realized that I was selling much

better to men’s magazines, I concentrated on them and didn’t do as many

“general interest” cartoons. My sales rate improved forthwith. The cartoon at

hand is one of this nefarious concentration. It’s a terrible pun of a joke, of course. But apart from the appealing dishabille of the femme, it’s the atmospherics that I like in this cartoon—all the basement workshop accouterment, the light fixture dangling from the ceiling, the tools on the wall and the workbench. The pose itself require a certain ingenuity, but the crowning visual achievement, I think, is in the shading—two thicknesses of vertical lines creating the dim and dimmer gloom of the basement. The perspective of the stairway is a little off, perhaps—but who notices? Our

second exhibit is a relic with a extended history. Tom Pilcher with Gene

Kennenberg produced several years ago two hardcover volumes entitled Erotic

Comics, covering the whole genre from 19th century France

through Tijuana Bibles to Undergrounds to Europeans (who are much more explicit

than we are) and much more. Naturally—for reasons I needn’t mention (surely)—I

bought them both and discovered, thumbing through the first volume, this cartoon

of mine buried in the fine print of the bibliography at the end. I like a lot of things about the cartoon. The girl’s hair, for instance, and the comedy of the extreme garment that is exaggeratedly pushing her up and away. The body language of the two men is pretty good, too, I ween: one blase and casual, the other intensely hypnotized by what he’s seeing, hand gripping the arm on the chair. White knuckled. The husband’s pose is nicely achieved—leaning to one side, elbow resting on the chair’s arm; legs crossed, left foot turned sideways at the ankle. And I like the cigar smoke, too—wafting ceilingward—and the shag throw rug. Not bad. And

here, by way of further elucidation, is the rough sketch for the cartoon. Looking at the sketch, you can see my notations directing the shifting of two of the visual elements around—the girl, move to the left; the chair with the husband in it, raise up in the composition. These shifts isolate each of the visual elements so they can be quickly seen and understood. Easy to do in the final tracing: just move the paper around. Interesting to me is the amount of detail in the sketch—the glass on the side table, f’instance, and the shags in the shag rug. I’m amazed that I took the trouble to add such nonessential ingredients to the composition. The final drawing is not much changed, but in the sketch, you can see where I’ve drawn several lines, finally deciding on one and making it darker than the others. Fascinating, I’m sure.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE LATEST

RIGHT WING NUT FIASCO in Arizona came to a cringing halt when Governor Jan

Brewer vetoed this rampantly fascist law, but not before a few of the editoon

fraternity had their way with it. Laws like the one proposed in Arizona would legalize discrimination. Under the banner of “religious freedom,” religious zealots and other bigots intend to enact “homosexual Jim Crow laws.” And no one’s religious freedom is protected under such a regime. Signe Wilkinson, next on the clock, shows how it works out if the Constitution actually permits the sort of prejudiced selectivity that Arizona law would have fostered. As Andrew Sullivan says at his website: “If we reopen the door to legal discrimination to satisfy conservative Christians, bigots could claim the right to refuse to employ Muslims, sexually active single women, or Mormons.” But what about those businesses that have been forced to close down when they follow their moral convictions—Christian adoption agencies that refuse to place children with same-sex couples, for example. Should a black baker be forced to bake a cake for a Ku Klux Klan wedding? asks Kevin Williams at NationalReview.com. Should a gay restaurant owner be guilty of a crime if he politely declines to rent out his dining room to the Westboro Baptist Church for their annual “God Hates Fags” Sunday brunch? My guess is, probably not. I’ve been in many saloons with signs on the door that say the owner reserves the right to refuse service to anyone for any reason. I think maybe the owner has a right to do that. But he also must face the consequences if the surrounding community boycotts his business and shuts him down. Neither of these activities—refusing service and boycotting—is illegal, as far as I know. So for the time being (pending further thought), I suspect that the owner in question ought not face a law suit. The problem with the Arizona law was that it sought to protect businesses from legal action that was probably itself not quite legal. The issue of religious freedom claimed under the First Amendment’s prohibition against government establishing a religion is a wildly liberal interpretation of the plain language that simply aims to keep government out of the religion business. This has been interpreted as permitting people to worship (or not) as they please. Freedom of religion. And that’s all well and good. But one sect’s freedom to exercise its religious beliefs ought not to permit that sect to force everyone else (or anyone else) to abide by that sect’s beliefs. The sect is free to practice its religion but not to force anyone else to practice it. And so the nuns in Colorado who object to including contraception coverage in their employee health plan should not be allowed to carry their objection so far as to deprive their employees of that coverage. The nuns can eschew contraceptive devices and can encourage others of their religious persuasion to do the same. But that’s where freedom of religion ends. To go beyond that is to deny a similar freedom to those who don’t believe as the nuns do. One person’s freedom of religion should not become another person’s constraint or compulsion. Yet that’s exactly what those who want to practice their religion on non-believers aim to do. Religious liberty is not a license to enslave others who believe differently than you. Stick to your own business and let others do the same, I say. To return for the nonce to Arizona, Steve Benson at the lower right correctly interprets Brewer’s motive, seems to me, with a vivid image showing that her motive was not moral conviction but financial consideration. And I suspect that those Arizona GOP lawmakers who passed the law and then recanted were guided by similar motivation. So much for moral purity. We move to the “trust issue” that John Boehner (pronounced “borish bean-counting hypocrite”) raised last month with Bob Englehart at the lower left. And Englehart’s proposition is comedically complex: the old Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm wants Bronco Bama to fall backward, trusting that the GOP will “catch” him—but their well-publicized intention is to let him fall to the floor. The point is made more by the words than the picture, which merely sets up for the verbal complexity. But the image is nonetheless a telling one. The “trust issue” was raised when Boehner (pronounced “blatant bought-and-paid for”) averred that immigration reform won’t happen this year (2014), saying: “You all know for the last 15 months, I talked about the need to get immigration done. … It needs to be dealt with. Having said that, we outlined our principles last week to our members, principles that our members by and large support … but I never underestimated the difficulty in moving forward this year. The reason I said we need a step-by-step common sense approach to this is so we can build trust with the American people that we’re doing this the right way. “And frankly,” he continued, deploying another familiar Republicon device—the Big Lie, which is, admittedly, frankly and openly committed, “— one of the biggest obstacle we face is trust. The American people (including many of my members [who we are ashamed to admit are Americans]) don’t trust that the reform we’re talking about will be implemented as it was intended to be [my emphasis].The President seemed to change the health care law on a whim whenever he likes. Now he’s running around the country telling everyone that he’s going to keep acting on his own. He keeps talking about his phone and his pen. And he’s feeding more distrust about whether he’s committed to the rule of law.” The Speaker finished with this bombast: “There’s widespread doubt about whether this administration can be trusted to enforce our laws and it’ll be difficult to move any immigration legislation until that changes.” Well, now we know why this Congress has done less than any other in history (just to resort to the GOP tactic of the Big Mendacity) (it’s almost true, though—at least insofar as it applies to “modern Congress” not 18th century Congresses). And that gives me an idea about how we can save money, probably enough to retire the Deficit altogether. If the reason the House refuses to pass immigration laws is that the majority GOP can’t trust Obama to enforce or execute the laws, then the same reasoning obviously has applied to all laws that the House might have enacted. Hence, it has passed very few laws so far and will doubtless pass no more—at all, period. And if the House won’t act until the administration changes (until 2016, as Boehner [pronounced “roaring asshole,”] says), then we ought to leave them all at home and save salaries big time for the next two years. Why pay them when their avowed purpose is to do nothing? Here’s an odd (if typical of modern politicians) fact: John Boehner (pronounced “bought and paid for”), the son of a bartender, has been in public service all his life, and he’s a multi-millionaire. How’d that happen?

BY THE WAY (but not at all incidentally), Kirk Mitchell at the Denver Post reports that “a group of prominent conservatives and moderates, including former Republican U.S. Senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming, has filed a friend-of-the-court brief supporting gay marriage” in the Oklahoma case before the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. Many of those filing the brief are Republicans—all, however, “former” office holders no longer seeking election. So they can act out of moral or intellectual conviction without regard to the price they might pay at the polls for taking a position anathema to many conservative voters. Said one of the signers: “A lot of Republicans are not extreme on these issues.” That’s a good truth to know. Now all we need are some actual office seekers with guts enough to take the same positions, which some elected Republicons apparently support silently. And maybe that won’t be so far in the future as we might suppose, thanks to Simpson and his cohorts.

THE RAMPANT

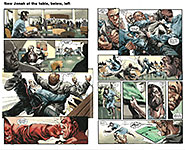

ILLOGIC of the Pachyderm’s so-called thinking is on display again in our next

visual aid. In other words, the so-called “job loss” that the GOP criticizes Obamacare for creating is actually helping the economy by creating job openings. What can be wrong with that? Doesn’t the GOP want that? Apparently not. Although I venture to guess that even the rampaging One Percent want people to be employed, to earn enough money to buy the goods and services that keep the One Percent up there, well above us hoi-ploy financially. Next around the clock, Tony Auth and Glenn McCoy confront the latest attempt to reduce the size of the U.S. military. Both pictures employ a image of obesity to make their points vivid. Auth’s point is that even with a slightly reduced budget, the U.S. armed force will be larger than any other country’s. What’s more, as Kevin Drum asserts at MotherJones.com, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s over-all budget proposal is actually $115 above the ceiling currently imposed by the GOP-dominated Congress under the ignominious sequester. So what’s to complain about? Obama, that’s what. Obama, the source of all GOP complaint, regardless of any and all other consideration, including logic and reason. One of the first Pachyderms to come out swinging at the Obama gang was our favorite Darth Vader, Dick Cheney, who immediately began prophesying doom to the American way of life if our military capability is cut at all. And as the GOP applauded Cheney’s growl, they apparently forgot that cutting the military—making it smaller but more agile—was exactly what Cheney’s protégé Donald Rumsfeld wanted to do before 9/11 upset his plan By way of giving the opposition a little airtime, here’s McCoy, another of the rampant right wing nuts, making the GOP point handily by comparing the money spent on entitlements to the trifling amount spent on the military—and implying, thereby, that maybe entitlements should also be trimmed. “Entitlement.” I’m not entitled to the Social Security stipend I get every month: it’s my money to begin with, and I merely loaned it to the government until I needed it. Finally, at the lower left, Rob Rogers gives us a disheartening image of “how far we’ve come” by comparing the deaths of two black youngsters 57 years apart. Have we progressed so little? Not quite. The white guy who shot Jordan Davis was, I believe, found guilty—albeit of a lesser crime than murder despite evidence to the contrary. If you point a gun at someone and shoot it, isn’t your intent to kill?

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “Just because someone makes a lot of money in business, it doesn’t mean he has special wisdom to offer everyone else. ... At conferences such as the World Economic forum in Davos, wealthy pooh-bahs gather to offer their ‘important insights on pressing public policy issues.’ But why ask for solutions to the worlds problems from ‘the people who benefit from the status quo?’ —Matthew Yglesias at Slate.com “A 2012 poll found that people who listened to no news were better informed than those who listened to Fox News.”—Charles Blow, New York Times About the catastrophic brain injuries likely caused by playing football: “The struggle playing out in living rooms across the country is that of a civilian leisure class that has created, for its own entertainment, a cast of warriors too big and strong and fast to play a child’s game without grievously injuring one another.”—Steve Almond in the New York Times

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing From The Week: The Coca-Cola Super Bowl ad that showed singers performing “America the Beautiful” in several languages sparked a backlash [among some of our more wild-eyed right wing nuts] and calls for a boycott [throughout their echo chamber]. “Coca-Cola is the official soft drink of illegals crossing the border,” according to one tweet. Former Rep. Allen West said the ad proves the U.S. is “on the road to perdition.” [And guys like him are lighting the way 24/7 with the dimmest bulbs around.]

READ AND RELISH “I am really just a daily journalist. I sit down every day to do it because I have to do it, and now I know how to do it. I actually do enjoy the act of writing, and it is that which means the most tome.”—V.S. Pritchett In an ad touting Robert Dubac’s “The Book of Moron,” this gem: “If Thinking Was Easy, Everyone Would Do It.”

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping WORDS AND

PICTURES, that’s what cartooning is all about. And our lesson today is about

just that—words and pictures, and just words. Below Greg Evans’ Luann, we have Brain Crane’s Pickles, wherein the joke is all verbal—and a good one, too (especially in giving the dog the last word, shades of the movie “10"), verging, as it does, on the brink of the verboten (i.e., mentioning flatulence in a comic strip).

YOU’D THINK

SOME THINGS ARE SACRED. But you’d be wrong, and Stephan Pastis would be

sure to show you the error of your so-called thinking. As he does here, in four

of his Pearls Before Swine strips from December last in which he

resurrects the sublime Calvin and Hobbes in order to imagine how the

principals are faring nowadays. It

is, however, a nasty rumor that Pastis is behind the marketing of those rear

window stickers for cars that show Calvin pissing on something. Pastis never

did that. And I’m here to refute the rumor. But I am not at liberty to say

whether his wife Staci threw him out or not, as reported in recent Pearls strips. Michael Cavna, on the other hand, is at liberty to reveal the whole story. It’s not that I didn’t try to resolve the issue. After a couple days of the “thrown out of the house” sequence, I wrote Pastis and asked him if Staci had actually thrown him out. The question was not as impertinent as you might think. Pastis has let the real world invade the precincts of his strip on other occasions. Several years ago on one of the five previous occasions that he was up for NCS’s Reuben, he used the strip to lobby on his own behalf. Or maybe he was merely telling his readers that he was a nominee for the distinction. Can’t remember. In any case, he doubtless knew at the time that NCS members would have already voted by the time the strips were published so his lobbying was purely in jest; but, still, it was a real world event in a fictional world. So maybe Staci had, indeed, thrown him out. Pastis answered my query with a cryptic: “Everyone has to have secrets.” So he thinks his dubious marital status is a secret? I wrote back: “Secret? Swine Pearls appears in now many newspapers?” More than 600 papers according to his syndicate’s publicity. So how many million people who are readers of the strip now believe that Pastis’s wife has thrown him out of the house? Lots, turns out. And that’s where the redoubtable Michael Cavna, proprietor of the Washington Post’s ComicRiffs blog, comes in. He contacted the cartoonist and got a civil response. Said Pastis: “Our real estate agent called Staci and said: ‘I have to tell you, I saw what you’re going through here’ … For a moment, it took us aback. We had to say to the agent: ‘No-no-no! That’s not real.’” Only Pastis’s fictional “meta-person” (known around the house as “Stephan Pastis,” not Stephan Pastis) was suddenly single. Their accountant also e-mailed to express sympathy. Then Pastis got a Facebook message from an Orthodox monk, who said he was praying for the cartoonist because of what happened. For the record, Pastis notes, of those three respondents, only the monk expressed concern specifically for the cartoonist. “So if we divorce,” he jokes, “I see where the sympathies lie.” Cavna continues: Pastis admits that he, of course, brings this all upon himself. He has created this snarky, paunchy version of himself as comic persona, he says, and the lines have blurred with readers. “The character is such a weird hybrid,” Pastis tells ‘Riffs. “Half of me considers him about as real as [the characters] Rat and Pig. But I do sort of use him as a real [stand-in].” But do Pastis’s loyal readers really think he would joke about a real-life divorce in his strip? “I guess that’s how little they think of me,” he says with a laugh. “But I don’t think anyone’s mistaken to think that” given his hybrid stand-in. Pastis also sees an upside or two to walking this gray-area tightrope between fact and comic fiction. “This is engaging readers — and anything to get people talking about the comic [is good],” he says. “It’s a productive alley. For a guy [like Pastis] doing book signings in 2014, it’s a perilous thing for strip cartoonists,” says Pastis, noting the times he has spoken to far more empty chairs than full ones — although he mostly draws large audiences these days. He says the hybrid character, in an odd way, has made him more famous. “There’s a ‘meet the cartoonist’ curiosity factor [when I do book signings],” says Pastis, adding that people wonder: Does he look like how he draws himself? Specifically, he notes, with a large stomach and always smoking. “You’re always branding yourself” as a creator, the cartoonist also points out. “What better way to brand yourself than to make yourself part of the product?” Then, Pastis notes, there’s the personal satisfaction that comes from storylines like his divorce arc — and the reader feedback that they generate: “I like that I disrupt Staci’s life.” As for the other two specimens at the bottom of our visual aid, I don’t get ’em. Maybe Mrs. Kowolski is the clue in Free Range, but I don’t know her. As for Funky Winkerbean, I realize that Lisa is Les’s first wife, who died of cancer, and that the woman he’s embracing is his second wife. But stitches on the fastball? You lost me, Tom.

COMIC STRIP

TABOOS is again our subject in the next visual aid. The last three on this exhibit are just favorites for one reason or another. I don’t know how many jokes you can make about a huge dog, but Marmaduke has been going for several centuries now (since 1954), seven gags a week. What I like, though, Brad Anderson’s pictures of the dog (often drawn by his son Paul). John McPherson haplessly ugly drawings add no beauty but visual meaning aplenty to a laughable firing squad gag. And Gary Brookins’ Plugger is me. The idea that old age brings wisdom is a deluded fiction. Old people are not wiser; they’re just quieter. The wisdom illusion is caused by old people’s realization that they no longer understand the world around them and so they say nothing about it anymore. Younger witnesses to this behavior (or nonbehavior) mistake the silence of ignorance for wisdom. It’s easy. Try it. Hey—if thinking were easy, more people would be doing it.

ONLY IN

THE COMICS, another

of our mini-departments, focuses on jokes that can be achieved only in this

medium. Here, f’instance, we have a Grimm joke in which speech balloons

are the McGuffin. Greg

Evans in his Luann has been dealing with adult subjects for several

years, here and there. And now that he has three romances going—Brad and Toni,

Gunther and Rosa, and Luann and Gill—the subject of sex lurks through the strip

fairly often. I’m surprised that Evans attempted this little tableau—since everyone reading this, including his co-writer, his daughter, knows that Luann’s question might get a more lusty response than Gill gives it. But sometimes double entendre is at the heart of good comedy, and it is here. The rest of the week is just as daring but with less risk of naughty repartee. As usual, Evans handles this kind of narrative with great delicacy, taste, and humor. The end of the sequence—with everyone going “woo”—is a beaut. Everyone, it’s clear, is relieved to have passed through the crucible of passion and emerged with innocence still intact. (If it weren’t, Luann in the second panel of the third strip here wouldn’t be pining for more.) (But she’s still relieved.) Nicely done.

NOTHING BUT

COMEDY here in Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy and Brian Crane’s Pickles. Next,

bad words you can’ use in comic strips. Jan Eliot of Stone Soup entitled

the first book of her strip’s reprints You Can’t Say Boobs On Sunday.

This otherwise unaccountable dictum is based upon the supposition that children

read the comics on Sundays—but not, apparently, on any other day, when

anything, seemingly, goes—as today’s crop of daily strips reveal by exposing

the collapsing taboos on “certain words.” And, in some cases, certain

“situations.” In Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy, Rob and his fuzzy friends discuss the words that can’t be used in comics by actually using the words, thereby tempting Fate. It’s a form of protest, I ween; and I suppose it worked. Somehow. In Mother Goose and Grimm, Mike Peters edges up to a statement about gays, who are not supposed to be mentioned in comics. Back to Get Fuzzy where Conley approaches the same taboo but dodges the issue by invoking a hoary stereotype in which gay males, to a man, frequent cosmetics. And finally, here’s Scott Adams’ Dilbert in which peeing is the topic alluded to (rather boisterously). I almost missed the joke here: the simplicity of Adams’ rendering of the robot tempted me to breeze by the last panel; only when I wondered what the joke was and went back to look did I see the that urinal was now the robot’s belly. Or was being held next to the belly. Adams also resorts to a visual device often deployed in days of yore by cartoonists to avoid a parade of talking heads: he shifts the focus from inside among conversationalists to a distant view of the building in which the conversation is occurring. When Leonard Starr did this in On Stage, we were treated to a spectacular drawing of a New York skyscraper (which Starr usually traced from a photograph). Adams’ version of this ploy is far less appealing visually. (And I can’t believe that he draws this box anew every time he resorts to it; surely, we’re seeing a recycled image in the second panel.) Still, we must admit that the visual variety he achieves by this maneuver is, er, stunning. (In the sense of numbing.)

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. ON OR ABOUT Valentine’s Day, Facebook added 54 new terms that people can use to indentify their gender. Among such time-tested stalwarts as male, female, man, woman, bi-gender and androgynous are a whole flock of designations new to me: cis, FTM, gender fluid, intersex, MTF, trans, two spirit, and, the champion—neither. “Neither” is problematic because the word negates both of two alternatives; in other words, implying that the gender universe consists of three—male, female, and neither. Those three are the only choices. But the list of 53 others denies that implication. Confusion, as you might suppose, reigns. Ahhh, it was ever thus.

MILEY CYRUS’s twerking may seem a raunchy attention grab, but “it shouldn’t be stifled or discredited,” wrote Matt Miller in the Denver Post, “because it has something to say in a form closer to the artist Marcel Duchamp than to soft porn. By doing whatever she wants, Cyrus is mocking the system that created her—the Disney machine, media and a culture that rewards normalcy. ... We should give her our applause, not our sneers, for doing something different, for challenging the very popular tastes that created her. All art should be evocative, and when it comes to Miley, even falling out of a plane can be insightful.”

About Those Political Colors. People who, for whatever obsessive reason, study colors, know that red is the eye-catcher in any array of colors: it leaps out at us first, screaming “Me, me, me.” Blue, on the other hand, is the color we go to second because it is sober and restful; we can be comfortable with blue. That’s why Democrat states are blue and Republicon states are red. White, on yet another hand, is no color at all; it’s neutral. That’s why the American flag is red, white and blue.