|

|||||||||||||||

Opus 314 (July 31, 2013). Once more down the rabbit hole to continue our Annual Open Access for one more week. This time, we report on the recently concluded San Diego Comic-Con, but the report includes more than merely photographs of cosplayers: we also compare the treatments of Siegel and Shuster with what DC afforded Bob Kane (debunking the myth about how much better his contract was), explain the origins of the Sandy Eggo Toucan, announce the guest co-star of the next Superman flick, review Chip Kidd’s wit at the Eisners, describe Harv’s plagiarism, review Howard Chaykin’s Wobblie Buck Rogers, cover the Zimmerman verdict in editoons, and outline the Locher Legend. And more. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Manga Editors Arrested John Lewis at Comic-Con Jeff Parker Retires Pope Francis Not to Judge

SANDY EGGO REPORT Movies and Movie Stars In Parking Lots Sergio, Steampunk, and Prince Valiant Upstairs in Meeting Rooms Quick Draw Siegel, Shuster and Bob Kane Myth The Eisners Calif Cartooners & the Rowland B. Wilson Steal Plagiarism? Beefs & Peeves: Toucan, Size, Security Galore Piling Rocks

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Mutts at San Diego Comic-Con Zits, Funky Winkerbean, Luann & Quill in Bed, Brad & Toni Static Strips in Alties Mostly

JIVEY WORD GAME SOLUTION

EDITOONERY Zimmerman Verdict Conversation on Race Other Issues Ding Still Pertinent

THE LOCHER LEGEND

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Chaykin’s Buck Rogers, Satellite Sam, Century West Dooley Interview with Chaykin

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits In Japan, three staffers at Core Magazine were arrested and accused of selling magazines and manga that had sexual content which was insufficiently censored, a violation of the Japanese Penal Code, which forbids obscene content. Anime News Network reported the story: “The three suspects are accused of selling about 24,500 copies of the manga magazine Comic Mega Store with sex scenes between males and females this past March. They are also accused of selling about 36,000 copies of Nyan 2 Club, a magazine for reader-submitted adult photographs. Both magazines were marked with the 18+ label.” “Earlier this year,” reported Betsy Gomez, “the production of Comic Mega Store was indefinitely suspended, and Nyan 2 Club has been under investigation. Both magazines have employed mosaic censoring, a Photoshop technique that pixelates sections of an image, to obscure content, but ANN reports that staff at Core had been warned that the amount of censoring was insufficient.”

MARCHING TO A DIFFERENT DRUMMER FOR A CHANGE Civil rights icon Congressman John Lewis was at the San Diego Comic-Con and found it rather mystifying. "It's so different!" he told Roxanne Roberts and Amy Argetsinger at the Washington Post. "I have never witnessed anything like it. Hundreds of thousands of people dressed in so many different ways. They looked like people from another planet or from outer space." The

73-year-old Georgia Democrat and veteran of 26 years in the House of

Representatives was at the Con to promote March, a graphic novel account

of his early years in the civil-rights movement—as one of the original Freedom

Riders, a speaker at the 1963 March on Washington and a chairman of the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Lewis, who collaborated with staffer Andrew

Aydin and artist Nate Powell, called the format "a way to reach

another generation through new means." So, what does a congressman wear into a room filled with wannabe Batmans and Katniss Everdeens? "I just dressed in a regular suit and tie."

THE CONTINUING RAPTURE OF EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS Jeff Parker, who has been editoonist at Florida Today for 21 years, announced in late July that he is retiring from the newspaper in order to concentrate on the daily comic strip he and Steve Kelley produce, Dustin, now syndicated nationally to more than 320 subscribing newspapers. Parker said he simply could not continue to produce both his editorial cartoon and the comic strip, which he draws. “I just can't keep up that pace anymore," he said in the Florida Today report. "Comic strips have always been my first love as a cartoonist, and creating a strip of my own has been a dream of mine since childhood." Still, he’ll miss drawing the editoons: “I know I'll especially miss drawing for Brevard readers and commenting on local issues that are important to me such as the space program, preservation of the Indian River Lagoon, our wildlife, and our ever-changing way of life. [Doing this work] has been a privilege,” he said, adding, “—especially having grown up along the Space Coast. It's a quirky, special place, and holds a quirky, special place in my heart." His last editorial cartoon for Florida Today will be published in early September. With his departure from the roll call of full-time staff editoonists, the roster drops to 50. The most recent departure was Sean Delonas, who accepted a buy-out and left the New York Post in June this year; Delonas immediately signed up to be syndicated by Cagle Cartoons.

“If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?”—Pope Francis. Immediately, the flocks of parsers lurking in pulpits and pews descended to explain that what His Holiness said didn’t really mean what it seemed to mean. Too late. We all know, you can’t unring a bell: having said it, he can’t unsay it. And since he is infallible in such pronouncements, this should be the Last Word on the subject. “Who am I to judge?” Indeed, who are any of us? If God made mankind, then he made homosexuals, too. The Church thinks homosexuality is inherently a “disorder.” I’m no theologian, but I may agree. I think homosexuality is one of the natural states of mankind. It’s also abnormal, “normal” being a statistical proposition: there are more heterosexuals than homosexuals. But statistics don’t change the circumstance: homosexuality is one of the natural states of mankind; heterosexuality is another. So, like I’ve been sayin’: it takes all kinds—live and let live.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS From Jon Winokur’s Curmudgeon on “Drinking”: “When I read about the evils of drinking, I gave up reading.”—Henny Youngman “One martini is all right, two is too manyk, three is not enough.”—James Thurber “One tequila, two tequila, three tequila, floor.”—George Carlin “Water, taken in moderation, cannot hurt anybody.”—Mark Twain

THE SANDY EGGO REPORT International Comic-Con San Diego, July 18-21, 2013 Another 130,000 in Attendance “THE WHOLE IDEA of B movies,” saith The New Yorker on July 22, “is to strip out the boring stuff—plot, character development, etc.—so they’re all pin-wheeling stuntmen, morphing mutants, exploding big rigs, and heaving bosoms. For sixty years, the producer Roger Corman set the rules in this twitchy domain. ... Artistic vision, Corman cheerfully acknowledged, was a luxury. ‘Whenever we had a dull trailer, Joe Dante’—his trailer editor during the seventies—‘would say,

CUT TO THE EXPLODING HELICOPTER!!

Who says trailers must contain only shots from the film?’ Corman finished.” The

Sandy Eggo Con long ago began ignoring the artistic vision that could be found

in funnybooks and surged onward in worship of Hollywood’s exploding

helicopters. For at least the last ten years, movies have dominated the

four-day extravaganza. Movies are the focus of the largest displays in the

exhibit hall—towering configurations of fantastic creatures and scrapiron

machinery. And movies are the focus of the major comic book publishers: you

can’t find a comic book in the exhibits of Marvel or DC Comics. For at least the last ten years, it has been virtually impossible to describe in words alone the phenomena that founder Shel Dorf unwittingly let loose 44 years ago to celebrate comic books, old movies, and sf. But the editors at the Union-Tribune (the local newspaper that persists in calling itself only “U-T”) tried: “As it does every year, our city has been transformed into a distant galaxy of sorts—in and around the Convention Center, throughout downtown and beyond. Buildings have been turned into creative billboards, and cool interactive exhibits will be busy promoting upcoming motion pictures, television series, the latest video games and more. There will be legions of costumed characters—from superheroes and cyborgs to trekkies and zombies—parading through downtown. And, of course, plenty of A-list celebrities will pop in, adding to the excitement of it all.” Among the tinseltown excitements at the Con—: ■ Director Bryan Singer assembled Hugh Jackman, Halle Berry, Patrick Stewart, and Jennifer Lawrence for a panel on 20th Century Fox’s “X-Men: Days of Future Past,” due out next spring. ■ Tom Cruise made his Comic-Con debut at Warner Bros’ panel to promote his 2014 sf venture, “Edge of Tomorrow.” ■ Director Josh Whedon unveiled the title of next summer’s sequel to “The Avengers”—“The Avengers: Age of Ultron.” ■ Warner Bros announced that its 2015 sequel to “Man of Steel” will co-star Batman, thereby “uniting DC’s two most iconic heroes for one megamovie” gasped Entertainment Weekly in its post-Con report (August 2) on this year’s “nerdfest.” (“Geekfest” I can buy into, but “nerdfest”? A little too much sneer for me.) ■ And Marvel flew in from London the cast of its space opera, “Guardians of the Galaxy,” and showed snippets of the film-in-the-making that introduced the largely unknown characters whose deeds of derring-do the film records. “Marvel movies have become almost sure things at the box office,” said Brian Truitt at USA Today, “—last year’s ‘The Avengers’ and this summer’s ‘Iron Man 3' both eclipsed $1.2 billion worldwide, yet ‘Guardians,’ based on the comic book series, is a different sort of animal since the characters aren’t as familiar to mainstream audiences” as, say, Captain America, Spider-Man, or Wolverine. Marvel president Kevin Feige seems unfazed by the daunting prospect. Marvel’s slate of future films shows the movies the company wants to make every summer through 2021. Stars of the comic book movies regularly invaded the precincts of the Comic-Con. ■ Tom Hiddleston, playing Loki, the Norse trickster god in “Thor: The Dark World,” crashed a panel on Saturday morning to surprise fans. “It was one of the most exciting buzzes of my life,” Hiddleston confessed to Truitt at USA Today. “As someone who’s trained in the theater, 6,500 people is about the biggest gig I’ve ever played.” Yup—6,500 is the seating capacity of the Convention Center’s giant Hall H. ■ Physicist Stephen Hawking appeared in an introductory video at the start of “The Big Bang Theory” panel, explaining, “When I’m not playing Words With Friends, I like to think about the universe” and then began reciting the lyrics to the show’s theme song. ■ The “Ender’s Game” panel was remarkably free of the controversy that has stalked Orson Scott Card, whose novel inspired the movie. Card’s opposition to gay marriage resulted in his leaving a DC Comics Superman project some months ago, and during the panel, when a woman asked about it, she was shouted down with cries like “Let it go!” and “Leave it alone!” But writer/producer Roberto Orel addressed the issue anyway, saying: “You never want to invite controversy, and we were concerned with anyone who might have been hurt. But rather than shy away from the controversy, we’re happy to embrace it and use the spotlight to say we support LGBT and human rights.” ■ Comic-Con hero Harrison Ford, asked why he signed on to do the movie about aliens set to destroy humanity, said: “I was drawn to the complexity of the moral issue. And the complex moral issues that are involved in the miliary. The book was written 28 years ago, and it imagined a world with the ability to wage war removed from the battlefield. That is one of the realities of our life now, with drone warfare, but this was unknown 28 years ago.”

THE COMIC-CON SPREAD outside the Convention Center years ago, spilling into the neighboring Gaslight district of saloons, restaurants and other evening entertainment spas. Banners and posters festoon the vicinity, announcing the Comic-Con’s presence. In the last couple of years, “events” have joined the milling throngs on Gaslight streets. In nearby parking lots, temporary entertainment arenas were set up for the weekend. The History Channel set up a “Vikings” drama in one, where fans raced mini-Viking vessels in a mini-waterway for the chance to win an autographed Vikings shield; Axe Cop dominated another; and in yet another, A&E promoted its “Bates Motel” series’ return in the fall.

Next to one nearby hotel, a grassy area had been transformed into the “Warner Bros Lawn Con” where you get your photo taken with a Lego Batman. Not far away, fans of “Ender’s Game” can stroll through an exhibit promoting the movie. And there was a Walking Dead obstacle course in which terrified fans ran, climbed, and crawled to avoid being mauled by decaying corpses. The U-T’s Karla Peterson interviewed Bryan Scheidler, a youthful attendee who came all the way from Pasadena and had just experienced the “Ender’s Game.” Said he: “I like that all of the downtown is embracing the Comic-Con. I have a badge [admitting him to the Con] now, but the first year I came down, I didn’t. I just came down and people-watched and went to all of the sci-fi decorated restaurants. You don’t have to go inside to enjoy this.” True, outside in the streets you can see cosplayers and the rest of the multitude passing before you—superheroes and space critters, and t-shirts with fantasy slogans emblazoned: Don’t make me go all Dexter on you. The hardest part of the apocalypse is pretending I’m not excited. If I like comic books, am I comic “pro” or comic “con”? Join the dork side. Love beyond gender. You also encounter at regularly spaced intervals along the teeming sidewalks various worthy souls bearing large yellow signs with bold black lettering on them, advising you that unless you repent, you’ll surely go directly to hell without passing Go. The Jesus People are entitled to as much free speech as any of us, and we can scarcely fault them for preferring a populous venue to work, but I wonder about their sincerity. None of them, apparently, have read Matthew 6.6, wherein the self-same Savior whose grace they invoke advises: “And when thou prayest, thou shalt not be as the hypocrites are: for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and in the corners of the streets that they may be seen of men. ... But thou, when thou prayest, enter into they closet, and when thou has shut thy door, pray to they Father which is in secret.” Admittedly, Jesus was talking about praying here, and the Jesus People would no doubt say that parading around the streets with signs of exhortation is not praying. I disagree: if what they’re doing isn’t preying, I don’t know what is. Besides, my reading of Matthew 6.6 suggests that religion is essentially a private, personal matter—something between thee and thy God; not a household appliance to be advertised in the streets.

BUT INSIDE THE CAVERNOUS CONVENTION CENTER, you can wander the carnival midway and see all manner of wares on display for purchase—none of them promoted by giant yellow signs with bold black lettering. And you run into people you see only once a year. I came upon Sergio Aragones watching a gaggle of steampunk cosplayers being photographed. He feels tiptop, he said, having had hip replacement surgery since the last Con, which he attended propped up by a cane. It was a bad year, he said: he missed deadlines, and he dearly hates to do that. “I did seven issues of Sergio’s Funnies, he said, “and then, because I had this operation, I had to rest for a while. I was a year late with No.8..” No.8

begins with Sergio in self-caricature, as usual introducing the issue, and he’s

walking with a cane. By No.9, I’ll have discarded the cane in Sergio’s Funnies

just as he has in actual life. At the Eisner Awards ceremony, he introduced new members of the Hall of Fame and remarked, at the onset, how glad he was to be there, alluding to his surgical adventures. As we admired the steampunkers, I suggested that he do a Groo adventure in steampunk. He laughed. Maybe too much detail drawing on the gear wheels and other glittery gizmos. When, later, I ran into Mark Schultz, who writes Prince Valiant, and Tom Yeates, who draws it, I suggested the same thing. For a moment, Schultz toyed with the idea, envisioning Atlantis rising from the sea and coughing up steampunk gadgetry for Val and his knights to pick up. But they, too, were somewhat daunted by the detail that would infect the drawings. Cartoonist Bill Hollbrook (On the Fastrack, Safe Havens, and Kevin and Kell) came by the National Cartoonists Society booth while I was idling away my time. He introduced me to his sister-in-law, Erin Piesto, who once worked in AT&T advertising. She said that 98% of the cellphones at the Comic-Con are smart phones. And the cellphone traffic is so intense during the Comic-Con that portable towers (at least two, maybe more: my notes fail me) are installed to handle the load.

UPSTAIRS IN THE MEETING ROOMS, a bursting program ensued—18-20 sessions every hour with panels of speakers on the usual sprawling range of topics (gaming, movies, tv shows, and even some comic books). I spent most of my time eddying through the exhibit hall, but I attended a few sessions in the upper reaches, too. At a Spotlight session, Gene Deitch, encouraged by Jerry Beck and Leonard Maltin, talked about his character Nudnik and about making animated films. Every film ever made is the result of a series of compromises, he said, quoting Woody Allen: “The only 100% of a concept is when you first get the idea—then compromise governs what happens next. And if you end up with 60% of what you started with, it’s a huge success.” The next day, I went to one of the Comics Arts Conference’s 18 sessions. Billed as “an academic conference in the heart of the Comic-Con,” the CAC was invented nearly twenty years ago as a venue wherein academic scholars of comics could be brought together with practicing professionals to discuss the medium they both love. I was at the first one (representing both scholar and professional, as one of the founders, Randy Duncan, said; the other founder is Peter Coogan). Over the years, the scholars—who get points on their vitae for such appearances, and the points add up to career advancement—soon elbowed the professional cartooners off the stage, leaving a ringing motto in their stead: “Comic Arts Conference—Fighting for Theory, Jargon, and the Academic Way.” Not all stuffy scholarship, as you can see. The

session I attended, “Heroes/Creators: The Comic Art Creations of Civil Rights

Legends,” discussed “the rich history of creative collaboration between civil

rights leaders and comic creators”—particularly apt with the publication of March, a graphic novel trilogy co-authored by Congressman John Lewis, whose

civil rights adventures it relates, and Andrew Aydin. Partly, I went to

say “hello” to two cohorts from my Champaign, Illinois days—John Jennings and Damian Duffy, who have collaborated in numerous projects to raise

consciousness about the diversity of practitioners in cartooning. Also on the

panel were Joseph Givens and Stanford Carpenter. I also attended a tribute session for Fantagraphics’ Kim Thompson, the pioneering advocate for comics who died last month; see Opus 312. And I was on a late Friday afternoon panel celebrating Walt Kelly’s 100th birthday. On Saturday morning, I made the ritual pilgrimage to “Quick Draw!”—Mark Evanier’s invention in which he poses puzzles to Sergio Aragones and Scott Shaw, and they race to complete some sort of cartoon reaction. Example: Draw yourself being really, really angry. And then: Now draw whatever it is that makes you really, really angry. The best reactions are those that are also funny. Depicting what makes him angry, Shaw drew a fawning comics fan. Can’t remember what Sergio drew, but through the hour, he was clearly the best of the contenders. Shaw is no slouch, but Sergio is a master at this. The third contender was Neal Adams, an unlikely participant at this spontaneous sort of sketching, but he did much better than you might suppose. On

Sunday morning, I was back in the Comics Art Conference, attending “Superman on

Trial: The Secret History of the Siegel and Shuster Lawsuits,” which, moderated

by Heidi MacDonald, featured Brad Ricca, author of Super Boys, a recent biography of the creators of Superman, and the legal commentary of Jeff

Trexler. Someone in the audience contended that Kane had negotiated a much more favorable contract with DC than Siegel and Shuster had (because, according to legend, Kane’s father entered into the negotiation), but the Warner lawyer said that if that happened, there is no documentation of it. In fact, the only documentation is the contract Kane had, which was exactly the same as the one Siegel and Shuster signed at the beginning: it stipulated rates of pay and a 10-year term, subject, as usual, to renewal at the expiration of the term. But Seigel got greedy. While in the army during World War II, he’d been advised by a would-be lawyer that he and Shuster should be getting more, and so he decided to go for DC’s fiscal throat. And lost. And in this vicinity, a couple more pages from my convention sketchbook, including a caricature of me by Mad’s Tom Richmond, which he, in response to my suggestion, did on the title page of his book, which I’d just purchased, The Mad Art of Caricature. It took him less than 10 minutes to complete, speed as well as dexterity being among the qualifications of a top-knotch caricaturist. I then convinced myself to try to caricature Richmond, filling the rest of this page with my failures. The bottom one in the middle isn’t terrible, but the nose is all wrong. Oh, well; better luck next year.

THE EISNERS were awarded on Friday night, and, advised by Mark Evanier that the second volume of the Fantagraphics Pogo reprint series would receive an Eisner for the Best Archival Collection/Project, I went. I’d worked on it, after all—writing the annotations that explained topical references, vital to understanding Pogo. And, as Evanier predicted, Pogo won. One of this category’s losers, alas, was another Fantagraphics volume to which I’d contributed—this time, in a more substantial way, writing the introduction to Roy Crane’s Captain Easy, Vol. 3, in which I reveal the person upon whom Captain Easy is based. Well, you can’t win ’em all. The Eisners evening was among the most boring of my long ennui-filled life. Like the Oscars, it is a seemingly interminable line of people presenting and receiving little trophies. As with the Oscars, the managers of the event seek to enliven what they clearly realize is a tedious slog by varying the presenters and hoping for some sort of hilarity from each of them. The best pair of presenters consisted of Neil Gaimen and fellow Brit Jonathan Ross. Ross talked on, crisp British wit in a crisper accent, and Gaimen, playing Laurel to Ross’s Hardy, said nothing, enduring in beaming silence whatever insult Ross heaped upon him. Chip Kidd was the funniest at the podium. He was representing Chris Ware, whose Building Stories (which seems to be a box of blocks?) won every category it was entered into. The work was up for Best Lettering, and Kidd, who seemed increasingly looped as the evening wore on—even bringing his glass with him to one acceptance—made the most telling observation of the evening: “Giving Chris Ware an Eisner for lettering is like giving Frank Lloyd Wright an award for doorknobs.” Ware’s Building Stories also won Best Publication Design, Best Writer/Artist, and Best Graphic Album, the last presentation of the evening. Kidd mounted the stage to accept it but went straight for Gaimen, whom he kissed full on the mouth. It was the punchline to a running joke that Ross had inflicted on us all. In 2007, it seems, Ross, over-reacting, as is his wont, to a current phenomenon—namely, the international sensation of Britney Spears’ kissing Madonna on the lips (or vice versa)—over-reacting, as I say, Ross planted one on Gaiman, seeking, one supposes, to create yet another international sensation, this time with himself in the spotlight. Ross alluded to this notorious incident several times on this ceremonial evening, complaining that his ardor had not been properly reciprocated six years ago. "It was like kissing a [bleeping] trashbag!" He said Gaiman had made a mockery of the Eisners. Such snide allusions continued between the dispensing of the awards. And then when Building Stories won again, here comes Chip Kidd again, charging at Gaimen, who he grappled over the jealous protestations of Ross.. Afterwards, Gaimen spoke for the first time in the evening: "I have snogged my first man—and it was Chip Kidd.” Not, strictly speaking, true: Gaimen’s first man had been Ross in 2007. (Unless Ross is gay, in which case, Gaimen’s remark borders on a slur.) “Snogging,” incidentally, is a Britishism referring to sexual preliminaries, stopping short of actual intercourse; it is usually employed in connection with teenage experimentation. Many of the Eisner winners’ works I was not familiar with, and some nominees that should have won, didn’t. Philip Nel’s Crockett Johnson & Ruth Kraus was up for Best Educational/Academic Work; but Susan E. Kirtley’s Lynda Barry: Girlhood Through the Looking Glass won. Best Writer went to Brian K. Vaughan for Saga instead of Matt Fraction for Hawkeye. Vaughan won in every category wherein Saga was listed. Hawkeye, a superlative example of how cartooning can work, lost to Saga in every category in which the two competed. But Hawkeye’s David Aja deservedly won Best Cover Artist and tied in Best Penciller/Inker or Penciller/Inker Team with Chris Samnee, whose Daredevil is as well done as Aja’s Hawkeye. Other deserving wins included Tom Spurgeon for Best Comics-Related Journalism with his ComicsReporter.com. and Darwyn Cooke’s Richard Stark’s Parker: The Score. Another that should have won is Mark Cohen’s inspired Naked Cartoonists, self-caricatures of cartoonists in the nude, in the Humor category. Don Rosa got the Bill Finger Award for excellence in writing and took the opportunity the podium afforded him to recognize the pioneering work of the late Bruce Hamilton, whose Another Rainbow collected the work of Duckman Carl Barks in durable hardcovers and also helped bring about new work on the ducks. Inducted into the Hall of Fame were an assortment of the living and the dead, the latter mostly long overdue for this sort of formal recognition: Mort Meskin, Spain Rodriguez, Marjorie Henderson Buell, Howard Cruse, Lee Falk, Bud Fisher, Bill Griffith, Al Jaffee, Jesse Marsh, Tarpe Mills, Gary Panter, Trina Robbins, Joe Sinnott, Jacques Tardi, and (gracious—about time!) Thomas Nast; his absence from the list until now is almost as inexplicable as Panter’s inclusion.

ON THURSDAY NIGHT, “opening night” of the Con you might say, the local chapter of the National Cartoonists Society throws a modest wingding dinner at a waterfront restaurant, Buster’s, in the Convention Center’s neighboring Seaport Village. I sat down with my old friend Jim Whiting, who promptly introduced me to the woman seated on his left, Suzanne Wilson, who, Jim said, was the widow of Playboy cartoonist Rowland B. Wilson. “Do you know his work?” Jim asked. “Know it!” I exclaimed, “—I’ve stolen from him! Look,” I wheezed, producing one of my biz cards from a pack, “—see this drawing of me plugging my finger into a light socket? That is lifted almost entirely from a cartoon Wilson did when he was in college, drawing for the Texas Ranger, the campus humor magazine at the University of Texas in the 1950s.” Suzanne,

incredulous, laughed and questioned my sanity if not my veracity. I insisted

that I was being truthful, and after I got home, I e-mailed her the evidence,

which appears on the accompanying visual aid. “Another

of my favorite Wilson cartoons,” I burbled on, “also came from a 1950s issue of

the Texas Ranger. At the time, I was cartooning for the Flatiron, campus

humus at the University of Colorado, and we had an Exchange File with copies of

other university magazines in it. When the Flatiron was banned—after the

second issue to which I contributed (perhaps coincidental)—I inherited some of

the Exchange File, including several copies of the Texas Ranger, and

therein, I found another Wilson cartoon, my other favorite. It depicts two

Frenchmen sitting at a tiny table sipping wine. One of the men expresses his

high approval of the wine he is sipping, and the other, who is barefooted, says:

‘Merci, I make eet myself.’” I’ve included it with several other Texas

Ranger Wilson prizes in the accompanying exhibit. Given all the excitement drummed up recently here and elsewhere about plagiarism, you may be astonished at how readily I admit to swiping Wilson’s cartoon about suicide by lightbulb socket. I am not as excited about so-called plagiarism as others are. Cartoonists have long participated in a variety of imitative practices that may qualify as plagiarism. Neophyte artists in the Middle Ages apprenticed themselves to master artists to learn their craft. The better their copies of the master’s work, the higher in the regard of their fellows they stood. Most cartoonists follow this time-worn path of apprenticeship: to learn their craft as youngsters, they copy the work of cartoonists that they admire until they’ve mastered the fundamentals. Generic copying—as distinct from copying the work of a particular artist—continues in every cartoonist’s career. Every cartoonist is encouraged to keep a morgue—a file of pictures of things he might someday need to draw, things he doubtless could not draw from memory. Airplanes, locomotives, sports cars, famous buildings, the beach at Cannes, exotic animals, farm animals, costumes of bygone eras. If you need to draw a picture of a bucking bronco and if you have a good morgue, you can find a picture of it there. And then you copy the picture. And today, the Internet is the best morgue of all time. My point with all this waltzing around is that copying—what the lay public calls plagiarism—is deeply embedded in the accepted practices of cartooning. Swiping and switching. And using stereotypical symbols. Charlie Brown shows up regularly in editorial cartoons, symbolizing the unrequited loser or the guy who gets suckered every time into trying to kick the football. Last time in this corner, we noted the use of Sesame Street’s Bert and Ernie on the cover of The New Yorker. Plagiarism? Unauthorized use of copyrighted characters? So—no; I’m not upset much by imitation of this sort. Outright copying—tracing another’s drawing—that’s not acceptable. But imitating another’s composition, drawing it in your own style and modifying the image as you go, that’s not a crime. (Plagiarism, by the way, is not illegal.) I’m reminded of what another cartoonist, Elena Steier (who has a forthright grasp of facts that sink nuance every time), said about all this: “Cartoonists have a bunch of different words for plagiarism: swiping, switching, cloning, pastiches, homages, appropriation, and probably more that I haven't researched on wikipedia. It's like the eskimos and their many words for snow. [They have lots of words for snow because it’s so common.] If nothing else, that should tell you that EVERYBODY has higher standards than we have.” Like many of my cohorts, I modified my imitation. Wilson’s suicidal character leaves a note saying only, “Goodbye.” Presumably, given the collegiate setting, the guy is failing all his courses. In my re-purposing of the image, I added some visual information (shoes and socks) and created a visual pun about light and truth, suggesting, perhaps, that Truth may not always be as enlightening as we usually suppose—even, maybe, that Truth might set you free by destroying you. Comical equivocation, I’d say. In my cartoon, the suicide serves a larger purpose; in Wilson’s, it’s just a comical way of committing suicide. I don’t want to seem so casual about copying as to make it insignificant. It’s not. Good cartoonists don’t do that much overt copying. And whenever they do, ethical behavior demands that they credit their source if their copy is too exact. Copying is not the sin; letting others think someone else’s work is yours is. My copy of Wilson’s cartoon is too small, I aver, to permit me to give him adequate credit in the picture. I’m equivocating, of course, but I’ve always credited him for the notion whenever I’ve discussed my version of it. Lecture over. Back to San Diego.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY’S COVERAGE of the Comic-Con was another edition of the sort of preview the magazine produced the week before the event: a generous 14 pages but all about movies, mostly photographs of the stars who showed up for the Con. EW also plugged its own “all star” panels at which “discussions were often funny and always frank.” In a disarming opening paragraph of its coverage, EW announced “a superpowered miracle—the news out of Comic-Con 2013 was about actual comic-book characters.” News indeed. But not quite accurately put: the news for EW was about movies about comic-book characters. Cute. The magazine also published two notable photos, which I’ve posted at your eye’s elbow. The first, a staged melange of cosplayers; the second—well, it succeeds in being audacious about what the male population is usually thinking. In short, it’s the best representation of this profound truth I’ve ever seen. The deadpan expressions are the capstone of the composition.

BEEFS & PEEVES. As you (the older of you anyhow) may remember, the earliest logo for the Sandy Eggo Con was a happily grinning toucan designed by Rick Geary. When the On-High Moguls changed the name of the Con to “International Comic-Con San Diego,” they sidelined the toucan and adopted an eyeball framed in a square. (Why an eyeball? Probably because of the “I” in International. Just guessin’.) That was a grievous mistake: it removed any tinge of personality from the Con. But

Geary’s toucan still shows up from time to time—lately, decorating Comic-Con

org’s blog, Toucan. And this year, it showed up in steampunk regalia. A beauty

of a drawing, as you can see here (a reprise of the opening illo in this

report). The next time I went over—earlier in the day, shortly after it opened—no line, but the t-shirt I wanted was sold out. So I content myself with the photo you’ve just seen. The insouciant bird, incidently, wasn’t designed as a toucan: Geary lately revealed that he’d set out simply to draw a bird with a big beak. It was subsequently decided that his big beaked bird was a toucan. The Con’s complete breakdown in how to sell a t-shirt is a minor matter, but it is symptomatic of the larger issue—namely, largeness. The Con has become too large to manage efficiently. One of the consequences is that registration and housing have been completely computerized, and the digital program attempts to accommodate too much diversity. Or so I suppose. Getting registered is very nearly impossible. And getting a hotel room in the downtown area graduated into completely impossible several years ago. The very hour that housing opened online last winter, the first message you read at the Comic-Con site is that no rooms were available in downtown hotels. None. In common with most conventions, exhibitors and special guests are given priority in hotel reservations. And at Comic-Con, there are enough in those categories to occupy all the downtown hotel rooms. And the room rates throughout are higher than they should be. The city values Comic-Con. According to the U-T report, those attending the Con typically spend in the aggregate upwards of $77 million all over town—in bars, restaurants, on the trolley, renting pedicabs and hotel rooms. Hotel taxes produce another $2.5 million in revenues for the city. Altogether, the newspaper estimates that the Con pumps $175 million into the local economy—plus spending on ancillary events and attractions not directly connected to the Con. “Without a doubt,” the U-T editorial concludes, “Comic-Con has a deep and wide impact on San Diego. That is why we must keep it here.” Keeping it in San Diego means expanding the Convention Center. A few years ago, Comic-Con management almost moved to another city—Los Angeles or Anaheim. San Diego convinced them to keep it in town by promising to expand the Center. And to control hotel room rates. Plans for the former promise are already in hand; the latter one falls a little shy of expectations, I’d say. I paid $177 a night at the hotel I stayed in. The regular rate, cited online, is $258; the Priceline rate is $229. The percentage of discount from those rates is 32% and 23%. I checked a few other hotels. The discounts represented by the Comic-Con’s convention rate came in at about 25%; but only 15% off Priceline’s cut rates. Given the business (see above) that the Con represents, the discounts ought to hover at around 40% below published rates, not 25%. Why don’t they then? Two reasons. Both reveal hotels’ subversive motivation. First, in the summer, San Diego is a popular tourist destination; vacationing families doubtless would fill the hotel rooms without any help from Comic-Con, and those families would be paying top dollar, not discounted rates. What’s the motive for giving up those vacationer dollars, which hotels must do to hold blocks of rooms for Comic-Con attendees? Not much. Second, the cost of the Convention Center expansion will be financed almost entirely through an assessment on hotels. So hotels want to rake in as much as they can while they can, like squirrels storing nuts for the winter. However greatly the city wants Comic-Con to stick around, the hotel community is not highly motivated to offer greatly reduced room rates. So they don’t. Most of my other complaints about the Con also arise from its size, the gargantuan horde and what must be done to control it. For instance: because of the multitudinous mob of attendees, you could get into the Hasbro Toy Shop only if you had a ticket. The tickets were free. But on Friday, all the tickets for that day had been issued by 11 a.m. Rules aiming at crowd control and safety bloomed in every niche and corner. In the largest meeting rooms—the ones into which the anticipated big crowds would gather—numerous signs advised that there was no smoking and that you couldn’t save a seat for your spouse or friend. In the central block of meeting rooms, traffic was strictly controlled: one entered meeting rooms from one hallway and exited into another hallway. No exceptions. If you made a navigating error and walked down the “entry” hallway past the room you wanted to enter, you couldn’t turn around and go back: that would be “exiting” and “exiting” on an “entry” hallway was forbidden. One of an army of security guards would stop you and make you go the other way. Once in the Convention Center lobby, I had stopped to talk to a friend whom I had chanced to encounter. We talked for maybe two minutes before a guard came up and told us we couldn’t stand there and talk. We had to be moving. We had to walk. The lobby was for walking, not talking. If we stopped to talk, we’d interfere with the flow of traffic, which didn’t want any stationary personages in the lobby: stationary personages might prevent the most expeditious exit for thousands in the event of a fire. One evening, I attempted to leave the building. As I approached a door, a guard standing at the door told me I couldn’t leave through that door; gesturing to his right, he said I should leave through “that door,” a door about 15 feet away. At “that door,” a guard was posted outside to make sure no one entered through that door, which had been designated an “exit” door. It’s reasonably easy to understand all these rules and precautions. They’re all in place to insure safety for thousands of milling human [sic] sapiens—safety and efficiency of traffic flow in a comparatively small space. But I occasionally shuddered: if our population continues to grow—doubling, say, in the next 50-70 years—the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con may be remembered as providing a glimpse at what life will be like in a densely populated geographic area. We’re approaching that situation. And Orwell’s Big Brother is already in place: all those police cameras in metropolitan areas, photographing your license plates as you motor about your business. Some carping citizens have already noted that the police, by following the time-marked photos of your license plate, can reconstruct segments of your otherwise private life—where you’ve been and when, and guessing from that data what you’ve been up to. Frightening to contemplate.

COMPENSATING FOR THE RIGORS of living in a too densely populated arena, I liked to walk along the waterfront early in the quiet mornings, listening to the water lap against the hulls of moored boats. Few people were out at that hour—joggers, mostly. I often ate eggs benedict on the porch of one of the waterfront restaurants, the Edgewater Grill and Inn. (Nostalgic: Colorado’s Edgewater is my hometown, and the Edgewater Inn thereof is a popular beer hall and pizza joint.) One afternoon, however, I found myself again walking the waterfront. In the afternoons, the walkway bustles with tourists and shoppers visiting stores in the Seaport Village. Various street-style vendors set up shop along the walkway; you can have your palm read at two of them. Last year, a guy had trained parrots that flew to your shoulder and sat there for the guy to take your picture with the bird eyeing your ear. But in this instance, even failure was restful.

TICS & TROPES Tom Richmond, Grady Hendrix tells us at filmcomment.com, “started at Mad in 2000, following some commercial illustration freelancing and a brief stint at Mad knockoff Cracked. He was one of the first of the magazine’s parody artists to work extensively in color, and to-date, he’s drawn 23 parodies along with a truckload of other stuff for Mad. ... I asked him what parody was the hardest to crack.” Richmond: “The ones that are hard for me to do are movies that I have zero emotional investment in, or ones that I’m bored with. If I really love or hate a movie, it makes it easier because I’ve got some interest in it, and I can really go after the details. For example, I really enjoyed ‘The Avengers,’ and one of the things I noticed was that in the couple of scenes that featured Gwyneth Paltrow—which are clearly just throwaway cameos to get her into the movie—she’s walking around barefoot, in a pair of shorrts and this bizarre blowsy white thing, and she’s in the same outfit weeks later when they’re supposedly rebuilding the headquarters at the end. And she’s still barefoot. So I thought, ‘What the hell is that all about?’ I decided that in the one panel she’s in, I’d have her with big stinky feet with flies flying off them. If I’d been bored with the movie, I’d probably never have noticed something like that.”

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Patrick

McDonnell celebrated

the San Diego Comic-Con with a week’s worth of Mutts squirrels’ pelting

superheroes with nuts; here, Iron Man and the X-Men. Next down the scroll of our exhibit, in Zits, we had a rare cross-over: Jeremy’s father, extolling childhood, is slowly transformed into the father in Baby Blues, the other comic strip written by Zits scripter, Jerry Scott. And Funky Winderbean, next on the scroll, ventures further into new territory: the old couple is celebrating a wedding anniversary, and the husband alludes to his Viagra dependency. I don’t know who these people are, though: ever since Tom Batiuk jumped his strip another decade or so into the future, the characters aged, and I don’t recognize them. Batiuk doesn’t help any by never (or too seldom) mentioning their names. Next

in our Vigil Gallery is another recent Zits. Alas, this visual concept is not original with Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman, Jeremy’s mentors. Facebook friend Josh Divine steered me to “A Little Difference between Men and Women” at Anvari.org, circa 2005. Same idea. Funny either way. But I think the off-on switch on Jeremy’s belly is a more fitting metaphor than just the switch all by its lonesome at Anvari. Both of the next two strips in our Visual Aid depict Luann’s reunion with her Aussie boyfriend. First, their first (or maybe second?) on-panel kiss. And then, demonstrating that Zits is not alone in veering off into innuendo-laced sexual waters (and lots of strips nowadays do), we get a peek at what Luann and Quill are doing in her bedroom. Nicely done. Incidently, I asked Luann’s Greg Evans about his other couple, Luann’s brother Brad and his hot fiancé Toni, who Evans often depicts sitting together on a couch in the livingroom—without saying whether that livingroom is Brad’s or Toni’s. “Are Brad and Toni now living together?” I asked. “Or is she just over at his place, or he at hers, from time to time? Hard to tell. Looks purposeful to me: you're committing a sleight of ... hand? Those of us who want to believe they're living together, can; those who don't, also can. You clever dog.” Evans answered my question with an encyclopedic: “To all of your questions, Yes.”

WE REALIZE that the newspaper comic strip has been invaded by “writers,” people whose sense of comedy and of the world is essentially a verbal sense. Pictures are incidental. A cartoonist, by definition, is someone who thinks in words and pictures—in combination, blended for a meaning neither achieves alone without the other. The writer invasion is particularly noticeable in alternative newspapers, where the likes of Tom Tomorrow reign. Aka Dan Perkins, Tom Tomorrow recently received a Herblock Prize for his work, which is usually illuminated by talking heads that he traces from photographs or 1950s advertising illustrations. Herblock probably turned over in his grave. The talking-heads-static-pictures fad takes an even more absurd form in such so-called “comic strips” as Red Meat, where the same picture (taken from copyright-free clip-art) is repeated for several panels. Near here, another of the same ilk. The

progression of static repetition here emphasizes the colossal silliness of the

joke, admittedly. But it a e words to go with the picture. A cartoonist, in contrast, conjures up a comedy in both words and pictures simultaneously, as a single act of creation. Moreover, the clip-art is increasingly dull and uninteresting as it repeats itself. In sharp contrast, we have below “Montage” a recent Blondie strip, which I clipped and pasted here because it is another in an increasingly long line of instances demonstrating how the strip keeps itself contemporary in artistic terms by varying the traditional Chic Young four-panel progression. The joke here is possible only if that second panel is wide enough to show both Dagwood and Dithers in the same setting. You don’t come up with a joke like this unless you think in both words and pictures as a simultaneous act of creation.

JIVEY WORD GAME And here’s the Solution to the Second Bananas word puzzle I poached from Jim Ivey last time. How many did you get?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy HEADLINE IN A WEEKLY NEWSPAPER in San Diego: “If Zimmerman is not guilty, then what are we?” A ponderable worth pondering. The

George Zimmerman verdict had been announced just moments before we posted Opus

313, so we scarcely had time to run the gamut of editoonist reactions. And

we’ve made only a cursory survey since, but the results fall into only two or

three categories. The second juror to speak out since the verdict also believes that Zimmerman got away with murder. But she also admitted that after holding out for second degree murder for most of the jury’s deliberations, she finally realized that the evidence for second degree murder just wasn’t there. She had no choice, she said. The next two on the clock offer less popular views. Steve Breen recognizes the importance of preserving the system of justice (whether or not the results are just) by referencing the Florida “stand your ground” law; politics should have no effect upon judicial procedures. Incidentally, although many believe Zimmerman won on the basis of the Florida law, his lawyers did not deploy it in his defense. Ted Rall alone among all the cartoonists whose work I saw delves somewhat into the complexities of the case. Is the Zimmerman verdict a racist result? Or is it a triumph of our justice system? Rall’s customary mode of commentary—a multi-paneled strip—permits him to “discuss” an issue like this rather than simply propounding a single view, a distinct advantage with a situation as layered as this one. One or two cartoonists wondered whether the verdict would have been the same if Zimmerman had been black and Martin white. These commentators have evidently forgotten O.J. Simpson; Rall didn’t. President Obama has been criticized by conservatives (and some liberals) for “bringing race into the Zimmerman case.” He did it at the very first by saying, in response to a question, that Trayvon Martin could have been his son. And he did it again in more extended remarks on July 19 in extemporaneous speech to the press corps at their daily briefing. It was an extraordinary display of his grasp of the issues and his understanding of their implications; I can’t imagine an aspect of the dilemma that he didn’t address in some way. And in every case, he poured soothing oils on troubled waters—exactly what a national leader is supposed to do. But race was in the mix long before Obama referred to it: it was on the minds of the African Americans who took to the streets to demand that Zimmerman be arrested. (I begin here one of my numerous diatribes on subjects alluded to in the editoons we are viewing; if you weary of such tedious prolixity, you can skip down to the next paragraph that beings with ALL CAPITAL LETTERS; that’s where we resume our examination of the current crop of editorial cartoons.) Obama, while not applauding the verdict in the case, nevertheless asserted that the judicial process had been followed, and “once the jury has spoken, that’s how our system works.” We must accept the verdict if we value the system. The reason for his comments, he said, was to provide some context—some historical cultural sociological context—that might explain the reactions of many Americans, particularly African Americans. He then talked mostly about racial profiling. Racial profiling draws suspicion from skin color. Although one juror said race didn’t enter into their deliberations, the Zimmerman case undoubtedly began with racial profiling. Zimmerman saw a brown-skinned teenager in a place where he maybe didn’t belong. Assuming he was up to no good, Zimmerman initiated a chain of events that left the boy dead. And then six jurors believed that a vigilante who had stalked an innocent back teenager was acting in self-defense when, during the ensuing scuffle, he shot the kid point blank. The context that Obama provided was the same context that W.E.B. Dubois discussed in his 1909 book, The Souls of Black Folk, arguing, as Michelle Alexander notes in Time (July 29), “that the defining element of African American life is being viewed as a perpetual problem—one’s very existence as a problem to be dealt with, managed and controlled but never solved. ... How does it feel to be a problem? ... Trayvon Martin will not be the last black boy wh dies or goes to jail or gives up on his life because he was viewed and treated as nothing but a problem. We are all guilty of being too quiet for too long. Let it be said hereafter that we were quiet no more.”

OUR NEXT

VISUAL AID continues our survey of reactions to the verdict. (Packwood apparently employs a mouse in the same way Oliphant employs a penguin; my rabbit, on the other hand, alludes to my name and was therefore initially attached to my cartoons in lieu of a signature even though these days, I always also scrawl a signature.) Next around the clock is Clay Bennett’s reaction, which, rather than analyzing the verdict’s moral implications dramatically stresses the practical consequences for young black men—a perpetuation of the dilemma they’ve been facing for a couple hundred years in this country, racial profiling. Below Bennett’s is Jack Ohman’s vivid image of the current state of relations between white and black Americans, a suspicious relationship that makes a “conversation on race” imperative but, also, unlikely to succeed. Steve Benson at the lower left finds a fitting visual metaphor suggesting why a conversation on race will be difficult: the cultural chasm that separates the races in this country is vast. The white guy’s comment—“I have no idea what you’re talking about”—underscores the difficulty we face. By asking for a conversation on race, Attorney General Eric Holder and Prez Obama and others who are urging it are advocating for candor as a way of establishing some sort of trust. Candidly, I believe that any such conversation must begin with participants straightforwardly explaining why they are uncomfortable in the presence of the other. Why do blacks make me uncomfortable—fearful? First, because I grew up in a town where there was only one black family; and none of those kids went to the school I went to, which was only a block away from their house (and mine). Where they went, I don’t know. All I know is, I didn’t go to class with them or play with them, the latter as much because they didn’t seem willing to join any of us other kids in whatever we were doing, even when we invited them. Second, as a result of my cultural isolation—my myopia—I learned what I know about African Americans from the news media. And for a long time, the only news about African Americans was about their criminal or a-social behavior. Even when, later as I grew older, I got to know some black people, the threatening reputation of the black criminal element lurked in the back of my mind. Lately, as the statistics about blacks killing blacks in inner cities emerge, that news is even worse. Writing in Time, Philadelphia’s mayor Michael Nutter (an African American) says “32 Americans are killed by gun violence very day, on average, a disproportionate number of whom are black men.” Naturally, that would make me (or any white person) fearful any time I encountered unknown blacks. In short, ignorance fosters racial distrust. Believing the stereotypes, we can’t see realities. And that’s true, I think, on both sides of the racial divide. As an adult, I didn’t encounter many blacks until, in my early thirties, I started working for a teachers association. The association began trying to make its African American members feel more a part of the operation, including representatives of racial minorities in planning activities and the like. On one occasion, the blacks were criticized for sticking together: in social situations—meals, parties—they’d sit together at one table instead of “integrating” the white population. We had a meeting about it, and I asked why they did that. One of them gave an answer I’ll never forget. She was a dignified woman of erudition and political acumen, whose manner of speaking was Authority Incarnate. She could read the phone book aloud and make it sound like Shakespeare. She and the other blacks collected together at social events, she explained, because they knew they’d be welcome in that milieu. She never knew for sure, she went on, when she entered a room with white people in it if she’d be accepted. I’d probably feel the same if I were the only white person in a room of African Americans. And it’s not a good feeling. Integrating schools was a good first step: at least, white kids who go to school with black kids aren’t ignorant about them; ditto blacks about whites. Familiarity may breed contempt, but I think it’s more likely to breed understanding or at least a sense of commonality. But we need be more black teachers. Black kids often resent white people in positions of authority, and, resentful, they do not engage in the learning process as well. They might do better if their teachers were black like them.

WE TURN NEXT

TO RELATED ISSUES—voting rights and immigration. The latest developments in

these areas, together with the Zimmerman verdict, tend to make race a major

issue in what we’d all supposed was a post-racial America. Jim Morin’s picture of the fortress-like wall that Republicons want to build along the border includes an explanation of the “real reason” the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm opposes reforming immigration laws: since newly arrived immigrants tend to vote Democrat, the more legal immigrants there are, the greater the demographic cataclysm for the GOP. Keeping immigrants out means preserving GOP power and influence. (Plutocrats rule.) None of which is breaking news: as Joe Klein observes in the July 29 issue of Time: “Ever since Richard Nixon’s ‘Southern Strategy’ in 1968, race has been the Republican Party’s tallest tent pole. ... There are strong conservative arguments about welfare dependency and the perils of Big Government that have nothing to do with race; I agree with some of them. But the Southern brand of conservatism that has dominated the party for the past 40 years certainly is built on a Confederate legacy.” Klein goes on to discuss the “creation of race-based congressional districts in the South”—initially conceived as a way of giving racial minorities representation in Congress. In districts gerrymandered to incorporate substantial populations of African Americans, the outcomes—an elected official who is black—is assured. But this maneuver, well-intentioned as it may have been, has a down side: it effectively “eliminated districts where politicians would have to appeal to both blacks and whites to win. This has been terrible for our democracy.” Mike Keefe’s cartoon at the lower left is more verbal logic (or illogic) than visual image, but the illogic makes the ol’ Pachyderm look as ludicrous as it is. And the drawing is a nifty rendering of Southwest landscape.

IN OUR NEXT

FORAY INTO VISUAL COMMENTARY, we turn to other issues of the day. Below that, more nonsense from Glenn McCoy. At first, I didn’t get it. I realized that it was a slap at the peckerdilloes of Anthony Weiner, but how, exactly? Then I remembered that Weiner is a Democrat, so McCoy is saying all Democrats are pricks, right? Another thoughtful insight from McCoy. Finally, Gary Varvel, inspired by the GOP’s tagging Obamacare as a train wreck, gives us an effective image about Obama’s delaying the implementation of one part of the Affordable Care Act. One can toy with the image. The part of the train most endangered is the locomotive, the thing that pulls it all. Does the locomotive represent the businesses mentioned in the speech balloon? And if businesses are the locomotive for Obamacare, what then is the fate of the whole project? And then, on the far side of the chasm, a solitary sign implies that the delay is motivated entirely by a desire to win Congress back for Democrats in the mid-term election. Our

next exhibit is more fun-filled. Not every editoon must be fraught with

Terrible Significance. From the height of the ridiculous to its summit, we ponder the return of Twinkies. Nate Beeler’s cartoon with the triumphant fat guy in front of the American flag with stars bursting in midair like fireworks makes the event ludicrous, but below his cartoon is John Darkow, who manages to put the Twinkie comeback to use as a comment on the return of Congress from one of its numerous recesses to the national capital—and to whatever it is they call “work” (taking the fun out of dysfunctional, I assume). Bob Englehart’s editoon at the lower left is a profound attempt to reconcile religion and science. Faith, clearly, unites them; and Englehart needs the multiple-panel construction to make the point. More

silliness in our next visual. Next, just funny one-panel cartoons—two at the top from Dan Piraro (the first appropriate in an opus reporting on the Comic-Con; the other, not so much). And then we have a cartoon from The New Yorker by Edward Steed. At first blush, it may seem an abdication of our responsibility to editoonery to conjure up such specimens. But editoonists often comment on fads and fancies of our society, and so, as we see here, do Piraro and Steed, and The New Yorker generally. We

continue in the same vein, somewhat, in our next display. The cargo shorts cartoon is a wild reflection on a clothing fad—the cargo pants idea taken to an absurd extreme. Besides, it made me laugh out loud, something I rarely do with a cartoon. The other two cartoons in this visual aid are both by J.N. Darling, the famed “Ding” of the Des Moines Register, where he drew political cartoons from 1909 until mid-century. I don’t have dates of publication for either of these two, but it doesn’t matter: I clipped and filed them because they are still pertinent. The one at the upper left is more sociological than political—a comment on the American brand of the human animal. And the other one is somewhat more political: the profiteering scamps we run down in a capitalistic society tend to be ourselves. Ding (an abbreviation of his last name, D’ing, adopted early in his career) wasn’t content with the image alone, telltale enough though it seems to me: he added the sign in the distance, “The Entire Population.”

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS William Stout, as everyone knows, is celebrated for his drawings of prehistoric critters. And some of those dinosaur drawings, according to Jared Earickson at examiner.com, inspired such movies as “The Land Before Time” and, even, the novel Jurassic Park. Said Stout, in response to a question about which art/project he was proudest of: “I am very proud of the first dinosaur book I put out. That kind of put me on the map with the public. It got me a 12-page spread in Life magazine. I met young paleontologists. I have been a member of the society of vertebrate paleontologists since the 1970s, and I go to their meetings every year. Young guys come up to me and tell me that they became paleontologists because when they were young, someone gave them a copy of that book.”

THE LOCHER LEGEND Dick Locher Retires After Four Decades of Politics and Cops and Robbers WE COVERED THIS EVENT twice before recently (Ops. 312 & 313), but I wanted to post a few of my favorite LocherToons and some photos, so I’m returning to the subject from a somewhat different angle. First, straight reportage—: Locher

retired from the second of his life-long cartooning careers May 1, 2013. He

retired from his other life-long cartooning career two years earlier. Locher is

one of the merest handful of newspaper cartoonists who did both editorial

cartooning and comic strip cartooning: he started doing political cartoons for

the Chicago Tribune in 1972; he inherited the iconic cops-and-robbers

comic strip Dick Tracy a decade later. He drew them simultaneously for

almost thirty years, rendering the strip in a markedly different style than his

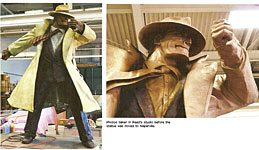

editoons. Locher is courtly in manner and mein, but his wit makes him eminently approachable. “Editorial cartoonists,” he was fond of saying, “are the towel snappers of journalism.” And that’s not all: “We watch the battle from the hillside, and when it’s over, we run down and shoot the wounded.” He had a million such quips. He did four-five editorial cartoons a week for distribution by Tribune Media Services. “Ideas are like grapes,” he said, “—they come in bunches but don’t last.” The more vituperative the cartoon, the more phone calls he got. “They question my eyesight and my brain,” he said. “You’re not a political cartoonist if you don’t get any death threats.” He’s received at least two. But that’s part of the job assignment: stirring up controversy, provoking thought and comment: “If you go down the middle of the road, you get hit by cars on both sides. Being an editorial cartoonist is like the blind javelin thrower at the Olympics: we don’t win a lot of awards, but we keep the crowd alert.” Locher’s bellicosity is deceiving. His editorial cartoons are tough-minded as well as funny, but in person, Locher is one of the last genuine gentlemen of the profession, full of years and wit, reason and compassion. And talent. Over the years, Locher reckons he’s had more than 10,000 cartoons published. "That's a whole lot of getting mad six times a week," he said. He has also racked up his share of awards and honors, including a Pulitzer in 1983. He had a private lunch in the Oval Office with President Ronald Reagan; and he created the coveted John Locher Award for college cartoonists to honor the memory of his deceased son, who once assisted him on Dick Tracy. And he paints and sculpts. He’s made several small bronze sculptures of presidential candidates. He designed the Land of Lincoln Trophy, awarded to the winner of the Illinois-Northwestern college football game. And the muse continues to pursue him: in his hometown of Naperville, Illinois, he’s working with Jeff Adams, owner of inBronze, a foundry, to perfect a statue of the founder of the town, Captain Joseph Naper, who started the place in 1841; see Opus 313. “This is so much fun,” he went on, speaking not only of making the statue but of a lifetime drawing pictures “I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I never went to work a day in my life.” This

isn’t Locher’s first larger-than-life statue: four years ago, he finished a

towering likeness of the iconic comic strip detective he drew for 28 years:

Dick Tracy, like the Naper monument will be, is part of the city’s Century Walk

public art collection. The idea for the sculpture was conceived by Naperville Century Walk Corporation president W. Brand Bobosky and Locher, a 40-year resident of Naperville. Locher had sculpted a Tracy maquette, and when he showed it to Bobosky, the latter thought it would make a beautiful life-size statue, joining the more than 30 public art pieces the Naperville organization has installed in the previous 15 years. Locher’s concept was then turned over to Wisconsin sculptor Don Reed who transformed the maquette into the 9-foot tall, one-ton sculpture. Reed was intrigued with the challenge of capturing the structure of Tracy’s angular face, the flow of his hallmark trench coat and the sense of energy and motion Locher conveyed in the maquette. Two

years ago, on Sunday, March 13, 2011, the last Dick Tracy produced by

Locher appeared in the nation’s papers. And in it, Locher takes a well-deserved

bow for himself. Dick Tracy wasn’t his only experience at syndicated stripping: for a short while in the late 1940s after he got out of art school (and before enlisting in the Air Force, where he was a test pilot), Locher had assisted Rick Yager on Buck Rogers. And just before he inherited Dick Tracy, he had been working with Jeff MacNelly, the other Chicago Tribune editorial cartoonist, on a topical commentary strip called Clout St., which he left soon after starting work on Tracy. Locher began drawing Dick Tracy when Rick Fletcher died in early 1983. Fletcher and Max Allan Collins had been doing the strip after its creator, Chester Gould, retired in 1977. Locher continued with Collins until 1993, when the syndicate elbowed Collins out of the picture and hired Mike Kilian to do the writing. Kilian was a journalist by day, and by night, the author of a series of mystery novels set during the Civil War. Locher's

connection with Dick Tracy goes back to 1957, when he began a

four-and-a-half year stint as Gould's assistant. More details of Locher’s legendary career can be found in Harv’s Hindsight for March 2011, whereat I post my 1994 interview with him. But before you dash off to read that, here are some of my favorite Locher editoons (I love his drawing style), culled from the Reagan years onward—and a batch of photographs I took of him in his Tribune Tower studio when I interviewed him there.

CLIPS & QUIPS Gilbert Hernandez’s graphic novel Marble Season, “a winsome and quietly comic story of three Mexican-American brothers growing up in the U.S. in the sixties, may well be the most surprising thing its creator has done to date,” writes Tim Martin at telegraph.co.uk. “Not because it’s good (it is) ... but because it’s about the last thing you would have expected coming from this cartoonist.” So what’s next, Martin wanted to know. “After this,” said Hernandez, “I’m going to do a collection called Children of Palomar, which is going to put me back in the ‘Gilbert Hernandez is doing what he’s supposed to be doing’ thing. But what I’m working on now is the next Fritz book, where I get to push myself over the top with gangsters and all that stuff.” He laughs with relish. “I’m going to ruin my reputation as being a serious cartoonist again.”

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Thing of It Is ... THE NEWSPAPER REPORTED this morning that Prez Obama offered congressional Republicons a new economic package “only to have GOP lawmakers immediately throw cold water on the idea.” So what’s new about that? I can write a lead paragraph for any legislative package Obama might put forth—tomorrow, next week, next month, two years from now— and after naming the package, I’d have the inevitable concluding clause: “and GOP lawmakers immediately threw cold water on it.” A predictable lot those Pachyderms.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE What I’ve Been Readin’ Lately: Howard Chaykin and His

Lewd, Depraved, Graphic Novels

WANDERING BY THE HERMES booth at the Sandy Eggo Con, I picked up the first issue of Howard Chaykin’s latest comic book enterprise, Buck Rogers. Hermes has carved a large niche for itself in Buck Rogers equipage: it’s up to the 8th volume reprinting the classic Dick Calkins/Rick Yager strip from its 1929 debut on. And Chaykin’s version of the 25th Century adventurer gives him a more contemporary patina. Chaykin’s tale, which he writes as well as draws, begins when Buck and Wilma Deering are already well acquainted and, wearing jetpacks, engage in a aerial fight with Killer Kane’s gang. Buck is another of Chaykin’s patented heroes—a flip, insubordinate wise ass, who, this time, keeps his pants on. Not only is that a change for a Chaykin hero lately: it’s a change for Buck, who, in the original saga, falls in love with Wilma, who is calling him “Buck darling” before the end of the third week of the strip’s run. Here, however, their relationship is even a little hostile, Wilma constantly reminding Buck that he is only Captain Rogers while she is Colonel Deering. In another new wrinkle, Chaykin gives Buck some unconventional political convictions. Buck is a fan of Eugene Debs, the early 20th Century socialist and one of the 1909 founders of the Industrial Workers of the World (known as the Wobblies), an organization that promoted the notion of One Big Union. Workers would be united in one social class and capitalism and wage labor would be outmoded. Buck fought in World War I as pilot in the famed Lafayette Escadrille in 1916, and his experiences “fighting and dying to keep our masters rich” have sold him unequivocally on the IWW program. War, he concluded, was always the same—workers killing each other in the name of some plutocrat’s lies.” For much of the first issue, Buck and Wilma are airborne in their jetpacks, firing at the bad guys members of rival gangs and trading snarky quips as they smash the heads of their foes into a fine mist of dark red. Buck wants them to fight the Han (presumably a Chinese outfit since China, the only surviving super power, rules the world) instead of skirmishing with Killer Kane’s gang or Black Barney’s. (Barney is of African descent.) The book satisfies the criteria I set forth for an admirable inaugural issue. It offers several completed episodes, but most are fighting sequences, which, although resolved favorably for Buck and Wilma, are somewhat boring —except for the banter between the two. That reveals personality—all to the good. But the best episode for showing character is the flashback depicting Buck as a worker in the ranks of the Wobblies. Buck’s political convictions are tantalizing enough to make me want to know what Chaykin will make of this unusual aspect of his story. Chaykin’s linework is clear and clean, and Jesus Aburto amps it up with delicious coloring that mutes or blurs many of Chaykin’s quirky stylistic embroideries around lips and chins and eyes. So far, none of the erotic ambiance for which Chaykin has lately become infamous—no bustiers, garters, stockings and retro-style pin-uppery. His other recent launch, Satellite Sam, written by Matt Fraction, promises to be a differently tinged horse. The

promise of the lascivious cover, however, is not delivered in the pages of the

first issue. We are, it eventually emerges, on the set of a television show, and the story mixes television crew jabber with scripted speeches from the show, “Satellite Sam,” the star of which is missing for all but the last page of this issue, where he shows up dead, the victim, we assume, of foul play. While the crew plunges ahead to broadcast the show even without its star, a gaggle of investors show up to tour the set, and, later, they meet with Dr. Ginsberg (I think he’s the boss, but given the Fraction’s storytelling mannerisms here, depending upon incidental dialogue to do the introductions, it’s hard to tell.) It all goes swimmingly, though—glittering quips, slangy asides, close-ups of various heads talking, all bustling headlong at breakneck speed. Two other characters: Dick Danning, the director of the show; and a woman, Libby Meyers, perhaps the show’s producer, who goes looking for Carlyle White, who may be the “star” of the show but who winds up dead at the end. His son, Michael White, stands over the body at the morgue, calling the corpse “Dad.” Earlier, Michael White stepped into the broadcast void, impersonating his father playing the part of Satellite Sam. Or so it seems. Later, going through his father’s effects, Michael discovers boxes of photographs—all those pix of chicks in stockings and garters that decorate the opening and closing pages of the book. “Pop,” says Michael, “what the Hell were you into up here?” End of No.1. Unhappily for a first issue, the story does not give us a protagonist who is either recognizable or particularly likeable. Is the hero Michael White? He shows up only at the end of the issue. He rescues the broadcast handily, which speaks well of his potential as a leading man; but we know little else about him except that he is apparently dismayed at his father’s hobby of photographing retro pin-ups. And he looks like at least one other character, Dick Danning, whose distinctive feature is eyeglasses—and Michael is shown wearing specs, too. At first, I thought he was Danning. The book’s completed episode is the rescue of the broadcast in the absence of the show’s star. And while I don’t know or like any of the characters enough to want to find out what happens to them, I do want to know what Carlyle White’s preoccupation with retro pin-ups will do for the story. So I’ll be back. But not because Chaykin has made me a fan of any of his characters, as a first issue ought to. In black and white, all of Chaykin’s most irritating graphic mannerisms leap to the fore in this title. He’s taken to adding fine lines to faces where there usually aren’t lines, for instance. And he crams too much detail into every picture, creating the kind of visual confusion that color would normally sort out. Most of the backgrounds are painstakingly laid in with ruler and pen, the resulting rigidity imparting to nearly every scene an antiseptic visual sterility. Sterility aside, the art still seems a little muddy from time to time; Chaykin adds tone with a grease crayon (or something similar) and then layers on zip-a-tone dot patterns, creating a sometimes messy collage of blacks and grays. But he varies page design here more than in his last effort, the scabrous Black Kiss 2, which quickly became visually boring, every page alternating long shots in elongated panels with extreme close-ups of the speakers in little square panels, superimposed upon the elongated ones. Satellite Sam shows Chaykin still to be in an experimental mood, his saving grace over all others. Michael Dooley interviewed the artist in early July at printmag.com, and Chaykin, as always, is worth listening to. Here are some excerpts—: