|

||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 285 (October 31, 2011). Yes, it’s still

the Year of the Rabbit, although, as you can plainly see, he’s sweating the

approach (in two-three months) of the end of his lunar year. The Big Events of this posting include reviews of 13 of DC’s New 52 (concluding, not surprisingly, that all the sex and violence means DC is aiming for an older audience—at least adults in the mid-stages of arrested development) and Frank Miller’s controversial Holy Terror, with a passing glance at The New Yorker’s so-called Cartoon Issue and a smattering of editorial cartoons from the last month, plus news and gossip galore. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Dick Tracy’s 80th Boom’s Decision 2012 Marvel Layoffs? Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing New Yorker’s So-called Cartoon Issue Tablet Wars: DC vs B&N CBLDF Gets Seal of Approval Tarzan’s Back Turkish ’Tooner on Trial

EDITOONERY Indian Summer Steve Jobs & Khadafy and More from the Month of October

Newspaper Comics Page Vigil Baldo and Illegal Immigration

THE BIG NEW FIVE-TWO Reviews of 13 of DC’s New 52: Justice League, Action, Superman, Batman, Detective, Catwoman, Batgirl, Wonder Woman, Blackhawks, All Star Western (Jonah Hex), Suicide Squad, Mister Terrific, Voodoo Plus Plans to Revive (Again) Captain Marvel

Graphic Novel Frank Miller’s Holy Terror

Jim Ivey’s AnagramOrama

PASSIN’ THROUGH Charles Brooks Bob Artley

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Dick Tracy passed the 80th anniversary of its launch date on October 12. The bloodiest strip of its day, creator Chester Gould had the titular character kill his first miscreant on November 26, just a little over a month after the curtain went up. The victim was a thug named Crutch who had killed the father of Tess Trueheart, Tracy’s betrothed, during a robbery on the very evening Tracy had popped the question, saying he hadn’t had any breaks “as far as money is concerned,” but with Tess at his side, he vowed to “find a way.” The date of the strip’s second killing—Tracy’s gunning down Crutch—was a holiday that Tracy, standing over the body of the man who’d murdered his fiancee’s father, observed by saying it wasn’t a bad Thanksgiving. The strip’s current proprietors, artist Joe Stanton and writer Mike Curtis, celebrated the anniversary month by re-enacting the strip’s first sequence—but with a few significant differences. Their frame story is Tracy’s cohort Sam Catchem telling policewoman Lizz how Tracy joined the detective squad. Tracy, it seems, was not out-of-work (as he implies in the original sequence) when he proposed to Tess: he was a uniformed cop on the beat. In the inaugural sequence of 1931, police chief Brandon, knowing the young man wants to avenge the death of his would-be father-in-law, invites him, implausibly, to join the plainclothes force right out of civilian life. In last month’s encore story, Brandon promotes the street cop in order to enlist both his passion for catching the murderer and his proven ability. And in the new version, Tracy is not only already a cop: he’s also a Navy veteran. Altogether, a much more plausible scenario. Most of the tale unfolds in its historic pattern except that the hoodlum population of Chicago consists of an inordinately high number of personages familiar to long-time readers (and recent fans) of Gould’s pace-setting strip, a veritable roll call of Gould’s grotesques from future Tracy escapades. The robbery that results in Mr. Trueheart’s death is conducted by members of a gang headed by Big Boy (an allusion to Al Capone), who was Tracy’s first arch-foe. Ribs Mocco and Crutch, who were both involved in the original robbery and the kidnapping of Tess, are still on the loose. But the rest of the gang putting in cameo appearances includes such classic reprobates as Flattop, Blowtop (who, Flattop suggests, is a member of the “Top” family?), Pruneface, the Brow, Mole, Gravel Gertie, 88 Keyes, Itchy, and Shaky, plus Steve the Tramp and the kid who will henceforth be known as “Junior.” In

all, a thoroughly enjoyable trip down memory lane and a notable way to

REPUBLICAN PRESIDENTIAL RACE TO END IN NOVEMBER Even Bill O’Reilly is bored by the bloviation of the GOP contenders. “There are going to be thirteen more of these debates,” he grimmaced regretfully into the Factor camera the day after the New Hampshire showdown. “But you don’t have to watch them,” he continued with one of his notorious self-satisfied grins, “—I’ll watch ’em for you.” Fortunately, none of us—including the avuncular O’Reilly—will need to pay any attention much longer. In a week or so, Boom Studios will announce the results of its “straw poll.” Concocted as a promotional stunt, Boom’s “Decision 2012" flogs its biographical comic book series, one title for each of nine Republican hopefuls—including Sarah the Palin—plus Obama. “The decision is in readers’ hands,” saith the press release, “—it’s up to them and their orders to see who wins!” The print runs for each title will be determined by orders placed in August. Total print runs will be announced in November, “and the candidate with the highest print run wins!” Chances are good that Pecos Perry will win: the “polls” closed before he appeared at any of the debates and destroyed his credibility by opening his mouth and saying something. At the time everyone was “voting,” he was still the newly heralded savior of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm. Boom’s publicity touted the “once-in-a-lifetime” collectiblity of the books as well as the opportunity the stunt provided for participating in a historic event—the first ever comic book straw poll. Boom’s marketing mogul Chip Mosher is quoted in Comic Shop News where he stressed the “non-partisan” neutrality of the books while admitting out of the other side of his mouth that adherents of the candidates would like what they will find in the books. Each title, in other words, promotes its candidate and reports nothing to that candidate’s disadvantage. With so many cartoon characters running in the GOP race, it seems wonderfully appropriate that the outcome will be determined by comic books and their fans. A tentative irony hovers over the enterprise. Despite the emergence lately of graphic novels and big budget movies which give to comic books a certain cultural cachet, comic books still carry the stigma laminated on the medium by an earlier generation: anything deemed comic-booky is somehow juvenile and simple-minded. And that, I hasten to say, is a perfect characterization of the American political system as it has been conducted the last several cycles: campaigns have devolved into name-calling and the propagation of outright falsehoods. Actual issues and policy matters are left twitching in their death throes alongside the campaign trail. Moreso with the current crop of GOP candidates than at any other previous time. Rachel Maddow sees these elephantine aspirants as living in “Republicanland,” a place where all of the issues being discussed are fake. The debates are being conducted on the basis of “truths” that are not “factual.” The candidates nonetheless accept the falsehoods as facts because they are Republicans. They all agree that Ben Bernanke is the most inflationary chairman of the Federal Reserve in the history of the institution. And yet inflation under Bernanke is noticeably lower than it has been since the 1980s, when it was running at about 14%. Pecos Perry drew resounding applause when he asserted, without quibble or cavil, that the Obama Stimulus created “zero jobs” when, in the actual world, it probably created somewhere between 1.0 million and 2.9 million jobs according to most economists. Perry says Social Security is an abject failure and yet it is apparently working as designed for millions of retired Americans. And yet—all the GOP candidates talk of these easily disproved “facts” as if they were real. They’re all living in a fantasy—Republicanland—where Bernanke stokes inflation, the Obama stimulus created no jobs, and Social Security is a failure. A comic book country. And the Boom Studio straw poll validates it as a funnybook culture. Boom reports that any comic book that is ordered by fewer than 1,500 readers will not be published. Would that we could apply the a kindred rule to political candidacies throughout this heppy heppy land.

FLASH!!! FLASH!!!!! FLASH!!!!!! Boom Studios couldn’t wait until November. Once the orders were in for the Decision 2012 funnybooks, Boom blurted out the results of the “straw poll.” On October 6, a press release announced that Barack Obama had won, beating the entire GOP line-up. Among the Republicans, Sara Palin finished first, followed by Ron Paul and then Michele Bachman—cartoon characters all. None of the rest of the titles received the requisite 1,500 orders so books will not be published for (in the order of their finish in the poll) Mitt Romney, Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich, Jon Huntsman, Rick Santorum, and Rick Perry. As noted (painfully, now) above, I expected Pecos Perry to finish at the top of the heap because when the orders were being placed, he was just entering the race and hadn’t proved himself as dumb as a cinder block yet—that is, he hadn’t participated in a debate. But even before the first of these debacles, canny comic book fans apparently could tell he was too vacant -minded to run and voted him into last place. Bravo.

TROUBLE AT MARVEL? From ICv2.com: Marvel has declined to comment on reports circulating on October 21 (most notably, and first, on CBR) that as many as 15 employees in editorial and production roles are being laid off. At least one editor, Alejandro Arbona, has obliquely confirmed his layoff on Twitter. The layoffs follow the departure of Chief Operating Officer Jim Sokolowski, who was laid off a couple of weeks ago in a cost-cutting move. The rumors coming out of Marvel at New York Comic Con (October 13-16) were bleak, and included a reduced number of exclusive contracts for creators in the future (Andy Diggle has since revealed that he’s no longer under exclusive with Marvel), declining freelancer rates, projects that had been planned but were now being eliminated, and a general belt-tightening.

NAME-DROPPING AND TALE-BEARING Stan Lee’s POW! Entertainment and 1821 Comics introduced Romeo and Juliet: The War at the New York Comic Con (Scoop). ... Art and illustrated book publisher Abrams has signed a letter of intent to purchase SelfMadeHero, the London-based graphic novel publisher of such titles as Johnny Cash: I See A Darkness, already available in the U.S. Following completion of the deal, Abrams will launch a SelfMadeHero North American list beginning in 2012 (PublishersWeekly.com). ... For the first time, a graphic novel, Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout by Lauren Redniss, has been nominated as a nonfiction finalist for the US National Book Awards, announced on October 12. An excerpt can be viewed on the author's website, laurenredniss.com (RelaxNews). From DailyCartoonist: The Miami Herald has bucked the trend of cutting comics and has [increased its comics line-up by] four. In all, seven new strips were added. Three comics (For Better or For Worse, Barney and Clyde, and Shortcuts) were dropped. The new comics starting in both the daily and Sunday pages are Cul-de-Sac and The Argyle Sweater. The rest of the seven new comics were added to the daily line-up: Get Fuzzy, Luann, Rhymes With Orange, Dustin, and Defrocked. The DailyCartoonist.com reports that at the Library of Congress an exhibit that opened September 15, “The Timely and Timeless,” includes several cartoonists— James Gillray and Honoré Daumier, as well as modern and contemporary creators such as Jazz Age cartoonist John Held, Jr., African American artist Oliver Wendell Harrington, New Yorker cartoonists Charles Addams and Roz Chast; and comic-strip creators Bill Griffith and Aaron McGruder and Jan Eliot, who wrote about the selection of her work from very early in her career with Stone Soup: “Looking back at the early work, despite the awkward drawings, I love the ideas I pursued, and my willingness to be bold since I had little to lose when I only had one, rather liberal, newspaper. This strip was written when I was still doing just one strip a week (Universal used the best from that period, plus new work, to put together the first 6 weeks of strips for my launch). Once syndicated, it’s possible to feel intimidated by public opinion, be terrified of losing a paper, and these fears might lead a cartoonist to be overly cautious in what they produce—and that would be unfortunate. Unlike Web cartoonists, who have a lot of editorial freedom, and no real editors, we newspaper cartoonists reside in, and sometimes bristle against, a rather conservative landscape.”

CARTOONS CELEBRATED, NOT It’s that time of year again: time for The New Yorker’s annual Cartoon Issue, which has arrived, bearing the same half-hearted tribute as in previous years. The first such effort appeared in 1997, and it was a whole-hearted tribute: in addition to publishing a special “cartoon section,” the magazine included a couple of text pieces about cartooning. That practice, which genuinely glorified the arts and crafts of the medium, was never again repeated. Subsequent Cartoon Issues contained only a dollop or two more cartoons than usual but no articles about cartooning or cartoonists. Hence, my verdict that the Cartoon Issue is a half-hearted tribute. And this year is a repeat performance. Apart from an 18-page section entitled “The Funnies” (which title is, itself, a sort of back-handed way of describing the magazine’s cartoons, “the funnies” being a term often used in reference to the “children’s” pages of a newspaper), the Cartoon Issue contains nothing else of pertinence to the practitioners or their artistry. And the editors could have done timely articles on either (or both) of (at least) two cartooning current events. Steven Spielberg’s Tintin movie has just opened in Europe and will open here in December. Tintin’s creator, the authentically world-famous cartooner Herge, has be reviled lately for his supposed racism and his equally imaginary Nazism. A refutation of both slurs could have been launched in connection with a review of the “performance-capture” movie. But, no—not at the super-sophisticated New Yorker. (Here at Rancid Raves, however, we’re not too stuck up to come to the defense of one of cartooning’s masters; next time, in Opus 286, we’ll undertake the mission. And we’ll report on the movie’s reception in Europe, too—particularly in Belgium, where Herge is a national hero.) Or The New Yorker could have reviewed “Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine,” an exhibit currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. An article could have examined the careers of such vintage caricaturists as James Gillray or Thomas Rowlandson or Honore-Victorin Daumier, all of whom are present in the show with more than one picture. But, no—not at The New Yorker, which, founded on the principle that super sophisticates deserve regular ribbing, deserves a little jostling itself. Whatever else I might be tempted to say about the so-called Cartoon Issue I’ve said before on previous manifestations of the tribute—say, at Opus 270 or Opus 250. You can read those again and become attuned to my typical screed, which I could (but won’t) repeat (again) here. Here, I can add only a couple of observations peculiar to this year’s fiasco. First, the magazine commits the ultimate expression of contempt for a visual artform by printing several cartoons across the gutter of the magazine, thereby obscuring part of the art, desecrating it. How many is “several”? Five—five out of fourteen, or 36% of the single-panel cartoons in “The Funnies” section. How better to spurn an artform held in low esteem than to distort or disfigure it in public? In short, “The Funnies” section includes a substantial gesture of disdain for the medium this issue is supposed to be honoring. Second, half of the allotted pages are devoted to “comic strips” or cartoon vignettes in which pictures are accompanied by sarcastic or insightful text. Roz Chast is the champion of this kind of cartooning, and she gets two pages in which she re-visits scenes from her vacation in Utah and Colorado. One of them depicts a barren desert floor with a single cloud hovering over it; it’s captioned: “Emptiness, Utah.” You need the picture in order to discern any comedy in this array, but the affrontery committed by Zachary Kanin needs no pictures. Entitled “Breaking News 2012,” his comic strip consists of a series of “forecasts” of events of the coming year. Here are a couple: “The sea levels rise by five feet, but, in a dramatic turn of events, the land level rises by fifty feet.” “Six-pack abs fall out of fashion—the new big thing in 2012 is having four butts.” “The ‘missing link’ is finally discovered—surprisingly, it is a starfish with human breasts.” Funny enough, no doubt, but Kanin’s pictures add nothing to the hilarity. So why is his effusion included in the Cartoon Issue? The readers of The New Yorker dote on the cartoons, and the cartoons are first among the magazine’s contents that have elevated the periodical above all its fellows on the newsstand and throughout popular culture. The editors, however, don’t seem to share in the appreciation. They are all—with the exception of the art director and the cartoon editor—wordsmiths, not artsmiths. They probably don’t understand cartoons. It’s not surprising, then, that the Cartoon Issue has been such a lurching failure for 14 of its 15 incarnations. You might be persuaded from the haphazard treatment that The New Yorker is trying its best to ignore the cartoons it’s pretending to glorify. And I suspect that’s exactly the case. The first Cartoon Issue was dated December 15, as if it were conceived as a Christmas present for readers. In subsequent years, the Cartoon Issue has retreated, slowly, away from late December into late November. And then into early November. This year, it’s dated October 31. This is an insidious ploy: by moving the Cartoon Issue back in the calendar a little each year, you eventually can claim that last year’s Cartoon Issue is actually this year’s and thereby avoid publishing one of the things altogether. That’s how the magazine will eventually escape for at least one year performing a duty that it has evidently found odious. It is to weep.

TABLET WARS In a move seen as retaliation against DC Comics’ deal with Amazon giving its new Kindle Fire a four-month exclusive on digital versions of 100 DC graphic novels (including perennial bestseller Watchmen), Barnes & Noble, the world’s largest bookseller, is removing those 100 DC bestselling backlist titles from its 705 retail stores in the U.S. Books-a-Million, which operates 211 stores in 23 states, followed suit almost immediately, reported ICv2.com. Barnes and Noble maintains that it won’t sell any versions of the popular graphic novels if they weren't allowed to sell the digital versions as well, reported Molly Driscoll at csmonitor.com. (The print versions of the novels will still be offered through the Barnes & Noble website as well as available for special order at any B&N bookstore). "Our policy is that we won't stock physical books in our stores unless we're offered the content in all formats," Jaime Carey, B&N’s chief merchant, told the Wall Street Journal. "We want to maintain a premiere customer experience." But there’s a little more to the story. DC’s Amazon maneuver made its digital editions off-limits to Barnes & Noble’s Nook e-reader, which is being introduced this month, and Amazon priced some of the Kindle Fire books at $9.99, half the price of the print editions. In effect, DC seriously undermined the competitive environment. In a press release, Books-a-Million CEO Terrance Finley said: “We will not promote titles in our stores’ showrooms if publishers choose to pursue these exclusive agreements that create an uneven playing field in the marketplace.” Quoth ICv2: “We haven’t heard what the term of the DC exclusive with the Kindle is, but there will be a window of at least some months, including the all-important holiday season, with vastly reduced availability of those titles in chain bookstores. This will offer an opportunity for all of B&N’s competitors, and will undoubtedly hurt DC’s graphic novel sales through the end of the year.”

COMIC BOOK LEGAL DEFENSE FUND GETS SEAL OF APPROVAL The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, an organization that defends First Amendment rights for the comic industry, announced yesterday that it has inherited intellectual property rights to one of the most nefarious emblems of the Age of Censorship (self-censorship) in comics history— the Comics Code Authority Seal of Approval that was branded on the covers of all comic books that had passed the Authority’s inspection. "[The Seal] will now be associated with an organization protecting creativity as opposed to a force that stifled it," said Charles Brownstein, CBLDF executive director, who pointed out that this announcement [made on September 30] appropriately falls within Banned Books Week. "Anyone who's read a comic book in the last 60 years has had some superficial interaction with this icon, and to be able to harness it to raise awareness of the First Amendment and the dangers of censorship is a vastly good thing. "As the Comic Magazine Association of America was winding down they approached us to inquire whether we would be interested in receiving the Seal of Approval," Brownstein told Vaneta Rogers at Newsarama. "Through a brief, and fairly straightforward process, they assigned us the rights to the Seal for use as part of our fundraising and education program. It was a donation from industry's dying self-censorship body to assist its mature First Amendment defense body." The Comics Code Authority "stamp" of approval was established by the Comics Magazine Association of America in 1954 in response to a public outcry — including Congressional hearings — about violent and sexual content in comics. It was inspired, Rogers writes, in large part by Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent, which claimed that reading comics led to juvenile delinquency. "The Code was created as a means for the industry to survive a vicious witch hunt whipped up by moral panic," Brownstein said. "It was a self-preservation measure that the industry took to fend off a mob mentality that could have driven it out of business." “So in a way,” said Rogers, “the self-regulating stamp saved comics from a certain death. But it also self-regulated comics in a way that encouraged only child-targeted material—creating an expectation of comics always being ‘kid stories,’ a perception that permeates society even today.” “Those days,” said Brownstein, referring to the years after the imposition of the Code, “are a brutal illustration of how creativity can be crushed by the forces of moral panic. ... The Comics Code was a compulsory measure administrated by an external body that publishers had to adhere to in order to obtain distribution.” CBDLF’s use of the Seal will help with fund-raising because it can now be licensed for use on items for sale, including a current t-shirt from Graphitti Designs that sports the Seal as logo. "Certainly there are other opportunities to license the Seal, and we'll be glad to work with folks who want to propose ways to help us raise money using it," Brownstein said. The CBDLF is hoping attention to their acquisition of the Seal will also raise awareness of its current "Be Counted" campaign. The organization is hoping to raise $100,000 by October 31st by encouraging comic readers to become members. Even after that date, it’s not too late to do your part. CBLDF membership starts at $25 per year, and comes with a variety of benefits, including a Green Lantern membership card and addition to a member list at www.cbldf.org. Donors who give more can also receive gifts of time and items from creators. Visit cbldf.org for details.

GOING APE ALL OVER AGAIN Tarzan is

returning to comic books after a sabbatical of several years—just in time to

celebrate next year the 100th anniversary of the character’s

inaugural appearance in All-Story magazine in October 1912. For Nelson, the intriguing aspect of Tarzan is that despite being raised in the jungle by apes, he wants to be part of the human world. “There’s always conflict between his animal instincts and his desire to be ‘civilized.’ For me, that’s what makes him tick.” The big challenge in adapting a 100-year-old creation is in finding ways to get around the racial stereotyping that prevailed in Burroughs’ world. But “modernizing” is not part of Nelson’s vision.

Turkish Cartoonist To Be Put On Trial for Renouncing God From Hurriyet Daily News. A Turkish cartoonist will be put on trial for a cartoon he drew in which he renounced God. The Istanbul chief public prosecutor's office charged cartoonist Bahadır Baruter with "insulting the religious values adopted by a part of the population" and requested his imprisonment for up to one year. In

a cartoon published in the weekly Penguen humor magazine, Baruter

depicts an imam and believers praying in a mosque. One of the characters is

talking to God on his cellphone and asking to be pardoned from the last part of

the prayer because he has errands to run. But the renunciation occurs on the

wall decoration of the mosque, where Baruter hid the words, "There is no

Allah; religion is a lie” (circled in red in the accompanying reprint of

Baruter’s cartoon). Turkish Religous Affairs and Foundation Members' Union and some citizens filed complaints against Baruter, and the public prosecutor's office accepted the complaints and filed a lawsuit against the cartoonist. That’s what life is like in a country the government of which is operated at the whim of the nation’s major religion. Keep it in mind the next time some aspirant for residence in our White House is criticized for not being religious enough. Or for adhering to the wrong religion.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots “Silence is the language of the Almighty; all else is a poor translation.”—Jalal ad-Din Rumi “I opened a box of animal crackers but there was nothing inside. They’d eaten each other.”—Lily Tomlin “When those waiters ask me if I want some fresh ground pepper, I ask if they have any aged pepper.”—Andy Rooney “Ever wonder if illiterate people get the full effect of alphabet soup?”—John Mendoza

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted

NOTE: Since we posted Opus 284, we’ve corrected an error therein. In the Editoonery paragraph beginning “We leave NineEleven behind,” one group of editorial cartoons being discussed was omitted as a visual aid; it has now been restored.

Indian Summer is the term we apply to the especially balmy stretch of days that often occur during the middle weeks of autumn. Here in Colorado, Indian Summer is one of the state’s most beautiful seasons when the aspen on the velvet pinetreed slopes turn a brilliant yellow and fleck the mountainsides with their gold. One

of the profession’s most famous cartoons celebrates Indian Summer: it appeared

on the front page of the Chicago Tribune on September 30, 1907. John

T. McCutcheon, who would be denominated the “dean of American editorial

cartooning” a half century later, was stuck for an idea and his deadline

loomed. And then, inspired by a string of beautiful warm autumn days and

remembering his youth in Indiana, he conjured up the illustration at hand and

wrote the accompanying text. As early as 1919, said Stephan Benzkofer recently at the Tribune (October 16), the “famous” cartoon had become a “much-loved” annual event, and the Trib produced a high-quality copy “ready for framing” for purchase by enamored readers. Indiana State Fair reproduced it as a feature exhibit in 1928. At the Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933-34, it was a life-size diorama and was reproduced in a fireworks display. Neighborhood, school and social groups acted out “Injun Summer” scores of times—as recently, Benzkofer reports, as 1977. “One of the biggest dramatizations involved 1,100 school children performing it at Soldier Field in August 1941 as part of the Tribune-sponsored Chicagoland Music Festival. ... But over time, the cartoon came to evoke anger as well as nostalgia. As early as 1970, readers wrote letters complaining that the Tribune was running an ethnically insensitive feature that misrepresented the brutal reality of Native American history in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries. Letter writers also were unhappy with the text claiming that ‘they ain’t no more left,’ pointing out that Indians still lived and worked in Chicago.” In the 1990s, the Trib’s editors decided to end the annual ritual, public editor Douglas Kneeland said: “‘Injun Summer’ is out of joint with its times. It is literally a museum piece, a relic of another age. The farther we get from 1907, the less meaning it has for the current generation.” I disagree. Some of the notions in the text accompanying the cartoon may be insensitive in our politically correct age, but the imagery—the stacks of corn stalks morphing into teepees in a kid’s imagination—is still full of meaning for anyone who has ever been a kid. No matter. “Injun Summer” with its insensitive corruption of the name of the group it invokes is gone. But not, apparently, forgotten. Said Benzkofer: “The cartoon has a powerful hold over many Chicagoans. For generations of readers, ‘Injun Summer,’ despite its flaws, became synonymous with the magic and peacefulness of those last warm days of the season. And just last week, the Tribune received another request to publish it.” Thanks be.

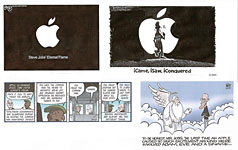

AND NOW, ON TO A CONTEMPORANEOUS autumn with a harvest of some editoons about the chief events of the last fortnight or so. (The last month, actually; I just like to use “fortnight” in a sentence.) Judging from the covers of numerous magazines on the stands over recent weeks, the death of Steve Jobs on October 5 was the most significant event of the season (if not the year—or, even, of our lifetime). His departure gave the nation’s editorial cartoonists a “snow day” on the 6th or 7th (depending upon newspaper’s deadlines). You could almost stay home and phone in a picture of Jobs at the Pearly Gates, teaching Saint Peter how to use an iPad. And many editooners drew just that. So did Barry Blitt on the cover of The New Yorker for October 17, showing the bearded old Saint with an iPad and Jobs looking on, entitling it “The Book of Life.” A few satiric penmen, however—fully aware of the highly probable likelihood that they would draw a cartoon that would be virtually the same as everyone else’s—managed a slightly different slant as we see in the adjacent culling.

Many of the cartoon eulogies deployed a sold black background and silhouetted against it the regnant Apple symbol. At the upper left, Pat Bagley was one of those few who managed a variant image by making part of the Apple the “eternal flame” to suggest Jobs’ impact upon the modern world. Going clockwise, Joe Heller produced another variation on the same visual, but added a caption that created another dimension (an idea repeated elswhere, too). Then Randy Bish used the Pearly Gates metaphor but supplied a novel app to the Apple. At the lower left—straying from the single-panel domain of most editoons—Darrin Bell in his strip Candorville undermined the eulogistic tenor of cartoon commemoration by reminding us all that Jobs’ messianic function did not include the sweatshop populations that produced Apple hardware. But Matt Bors ventured even further from the well-trod and threadbare as we see in his strip. Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs.com had noted that many editoonists in employing the Pearly Gates image apparently forgot that Jobs was a Buddist. Some cartoonists noted the oddity, too, “but one artist, Portland’s Matt Bors, has now rendered perhaps the most inspired response.” And Cavna goes on to annotate Bors’ strip: “With his cartoon, Bors deftly nails a satiric trifecta—lampooning the accumulated cumulus of Jobs cartoons that too easily invoked iClouds, iPads and the Christian imagery. And then, with a real beauty of a last panel, Bors mocks Apple’s own employment practices in China—ultimately tweaking even the pundits’ beatification of Jobs himself. Five panels. At least five satiric targets. Bors scores. How great his art.” Cavna goes on to quote Bors, whom he interviewed: “The cartoon struck a chord because it filled a void, left by my colleagues, for satire on Steve Jobs’ death. Anytime a figure is glorified the way Jobs was, there’s a backlash against it. People love to see the mighty brought down a peg, and there were legitimate reasons to criticize Jobs that were left unsaid after his death.” Cavna elaborates: “Bors also notes that his cartoon’s effectiveness was dependent on how many of his colleagues ‘went overboard’ with the Pearly Gates trope. ‘Many people think those [cartoons] are silly, so a self-aware comic mocking the convention was likely to be a hit.’ “Bors decided to wield both satire and meta-satire: ‘As an editorial cartoonist, I don’t consider any topic off limits for satire and criticism. That includes the recently departed—and editorial cartooning itself,’ he finished.” But Cavna wasn’t quite finished: he noted that California governor Jerry Brown declared Sunday, October 16, “Steve Jobs Day” in the left coast state.

WHATEVER HE WAS, STEVE JOBS was not an inventor. His biographer, Walter Isaacson, began his Jobs obit for Time by saying: “He didn’t invent many things outright, but he was a master at arranging ideas, art, and technology in ways that repeatedly invented the future. He designed the Mac after appreciating the power of graphic interfaces ... he created the iPod after grasping the joy of having a thousand songs in your pocket” in MP3. He was not an engineer. He was not a techie. Jobs was a tinkerer with the drive of a perfectionist and the instincts of a designer. At The New Yorker, James Surowiecki writes: “Jobs’ defining quality was perfectionism. The development of the Macintosh, for instance, took more than three years because of Jobs’ obsession with detail. He nixed the idea of an internal fan because he thought it was noisy and clumsy. And he wanted his engineers to redesign the Mac’s motherboard just because it looked inelegant. At NeXT, the company he started after being nudged out of Apple in 1985, he drove his hardware team crazy in order to make a computer that was a sleek, gorgeous magnesium cube. After his return to Apple in 1997, he got personally involved with things like how many screws there were in a laptop case. It took six months until he was happy with the way that scroll bars in OSX worked.” According to Isaacson, Jobs thought of himself as an artist. His passion was what he called “the whole widget”—the machinery, the software, everything had to be integrated into a user friendly (and physically attractive) package. And that passion resulted in gadgets that people wanted even though they didn’t need them. He was more P.T. Barnum than Thomas Edison said Jim Picht at WashingtonTimes.com. He sold us a new future. Nudging and cajoling (and often berating) the people who worked for him, Jobs revolutionized six industries: personal computers, music, phones, tablet computing, digital publishing, and animated movies. Although Jobs was by no means an animation professional, he enabled the most spectacular advance in animation in the last 50 years when he purchased Pixar from Lucasfilm in 1986 and put both his money and support behind it. “In the beginning, Pixar was a hardware store [for Jobs],” said Tom Sito, a Disney veteran. “But Steve was won over to the idea of making animated film by the successful short films that Pixar and John Lasseter were making” (like “Luxo Jr.” and “Tin Toy”). Said Jen Chaney at the Washington Post: “Company pioneers like John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton, as well as other creative storytellers and animators at Pixar, would ultimately be responsible for making those movies. But what is true for them is true for virtually anyone who has permission to be inventive in any field: they could not have achieved greatness without the finances that gave them the freedom to do it.” In his book, The Pixar Touch, David Price explains that it was Pixar, not Apple, that would ultimately make Jobs a billionaire.

INCIDENTALLY, Dennis M. Ritchie died on October 12, just a week after Jobs. We didn’t hear much about him, but he did more for modern computing than sell snazzy products. At Bell Labs, Ritchie, with Brian Kernighan, developed the C programming language, a versatile and portable language used for everything from embedded systems to graphic software; and with Ken Thompson, Ritchie developed the Unix operating system, which inspired the OS X system on the Mac. “In other words,” writes Denver Post columnist Ed Quillen, “just about anywhere you look in the digital environment, you’ll find some connection to Dennis Ritchie’s C and Unix.” But Steve Jobs’ death grabbed all the headlines. As he was accustomed to doing..

THE OTHER PRINCIPAL EVENT of recent weeks was the grab-ass slaying of Khadafy in Libya, and our concluding array of editoons begins with Milt Priggee’s celebration of that event.

Many of the cartoons on Khadafy’s death had the legendary nutcase tyrant of the Middle East in Hell, where he receives an assortment of comeuppances. Priggee, however, produced a striking detour from the easy route taken by so many of his colleagues: as we see at the upper left of our first exhibit, his cartoon evokes Bill Mauldin’s classic image at the death of John F. Kennedy, the sorrowful statue at the Lincoln Memorial. But Priggee’s smitten statue is of the Devil himself, mourning the loss of his most important missionary on Earth. Nice turn. Next on the clock is Bill Day’s reminder that Khadafy was nuts—er, daffy—employing an image familiar to movie-goers worldwide. R.J. Matson took of in another direction, presenting Khadafy’s death as a premonition for Syria’s Assad. With the last imagery in this quartet, Joe Heller shifts to a different subject—the supposed Iranian plot to assassinate the Saudi Arabian ambassador to the U.S. This one becomes a little farfetched if you attempt to assign actual correspondences to the images on the blackboard; too much of a stretch maybe. But the overall image is effective in conveying the idea that the evidence of Iran’s guilt is pretty obvious. With the next collection, we move to the broader if more disgraceful arena of American politics. At the upper left, Joel Pett’s image is of dirty laundry hanging on the line. He may not have intended precisely that interpretation, but I see it that way. Pett likely began with the concept of a “laundry list,” which he then hung out to dry. For all to see. And what we see is the same old boring GOP program once again. Well, maybe “dirty laundry” does apply. None of these “initiatives” worked the last time they were tried, so they’re used and therefore “dirty” like a previously worn and now smelly sock. (And that leads us to trot out the bromide that people who try the same things over and over, expecting different results every time, are demonstratively insane.) (And yet a vast number of tea lovers in this country advocate doing precisely that.) I applaud the revelation in Mitch McConnell’s utterance, but that, like the one leg amputated on Uncle Sam’s trousers, doesn’t seem integral to the over-all metaphor. McConnell’s speech is, however, the chief reason I picked this cartoon. A propos the GOP laundry list, our financial predicament and the plan espoused by McConnell and his minions, and the attitude of the entire slate of Republican prez candidates, here’s E.J. Dionne Jr. at the Washington Post: “So let’s see: the solution to large-scale abuses of the financial system, a breakdown of the private sector, extreme economic inequality and the failure of companies and individuals to invest and create jobs is—well, to give even more money and power to very wealthy people, to disable government and to trust those who got us into the mess to get us out of it. That’s a brief summary of the news from the Republican Party this week. It’s what Republican candidates said during the Washington Post-Bloomberg debate, and it’s the signal Senate Republicans sent in voting as a bloc against President Obama’s jobs bill. Don’t just do something, stand there. ... There’s no problem that can’t be solved if the federal government just does absolutely nothing about it.” Dionne concludes by explaining what Rep. Barney Frank meant with the concept of Reverse Houdinis: “They are people who tie themselves up in knots and then declare: ‘I can’t do anything because I’m all tied up in knots.’ We seem on the verge of putting Reverse Houdinis in charge of our government.” If they persist in this mode, they’ll inspire 99% of the population to occupy seats of power and government. Back to visual aids: next around the clock are a pair of La Cucaracha (“the cockroach”) comic strips by Lalo Alcaraz, who also produces an occasional editorial cartoon. But he, like Aaron McGruder before him, laminates his comic strip with political commentary. This is a straight-forward indisputable assault on the reasoning of banksters. No metaphors; no imagery. Just Cuco, the cockroach of the strip’s title, in sarcastic action. Again, I liked the message so much I saved the strips even though metaphor and imagery (except for the Monopoly character in the role of bankster) are not quite so active in conveying the message. Clay Bennett’s cartoon at the lower right, however, is rich in imagery. The champagne and the champagne glasses suggest wealthy imbibers of the product, the people who get to take their glasses from the top. They get all the champagne; none of it trickles down to the glasses at the bottom. And yet the glasses at the bottom are holding up the glasses at the top. Multiple meanings and a memorable image. Nicely done. Finally, we have Jimmy Margulies at the lower left. The metaphor is scarcely as complex as Bennett’s, but it conveys the message, and the image is undeniably persuasive and memorable—the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm’s attitude about funding emergency services would rob Peter to pay for Paul, leaving one or the other still in need of emergency services. In our last assemblage, we return to Bennett, whose metaphor for the peace talks between Israel and Palestine shows why it’s so hard to get the parties to the negotiating table. (I inadvertently added to the import of the image by scanning the cartoon upside down.) Next is Steve Benson’s telling imagery that reveals the hypocrisy of our national reaction to the Iranian plot to kill a Saudi ambassador on U.S. soil. Seems to me that we did something similar in Pakistan last spring. Bagley heaps up the sarcasm on the GOP positions on taxation. In his images, the Rich carry far less of a taxation load than little guys like you and me. And yet the insanely barking Republicans (Eric Cantor, Michele Bachman, Mitch McConnell, and Paul Ryan) choose to vilify us for paying less in taxes (even though, considering sales taxes and payroll taxes, we are paying a goodly portion). The hilarious hysteria of the scene makes it memorable. And Bagley’s seemingly tossed-off caricatures are deadly accurate. We don’t see much of Lee Judge around the country. I’m not sure who syndicates him. But his drawings at the Kansas City Star are crisply modern, and here, at the lower left, we can see that an unrestrained mad dog (“capitalism”) would tear the throat out of the average American worker. True, as far as it goes. But the rest of the metaphor would have the dog chewing himself up. The inherent flaw in capitalism is not so much that it makes victims and slaves of everyone at the bottom of the economic heap (although that’s an apparently inherent evil) but that it will destroy itself, too—in the greedy fulfillment of its own natural inclinations.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS Here’s one that drifted in over the Internet transom: The English language has some wonderful collective nouns for the various groups of animals. For example, we are all familiar with a herd of cows, a flock of chickens, a school of fish, and a gaggle of geese. Lesser known words are a pride of lions, a murder of crows, an exaltation of larks, and a muster of storks. Now consider a group of baboons. They are the loudest, most dangerous, destructive, obnoxious, viciously aggressive and unintelligent of all primates. And what is the appropriate noun for a group of baboons? Believe it or not— a congress! Not quite. A bunch of baboons is not a congress; it’s a rumpus. Which goes to show you: don’t rely on the Web for accurate information.

*****

“I believe that at some level when you get elected President, they take you into a room and there are five guys sitting there you’ve never met before, and they open up a book and go, ‘Here’s what’s really going on.’ And that’s when your hair first turns white. You walk out of that room like, ‘Holy fuck!’ So at some level, I have a great deal of sympathy for ‘heavy is the head that wears the crown.’ I don’t necessarily have a good Chicken Soup for the Soul piece of wisdom for him [Obama].”—Jon Stewart

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing Here’s a treat: on YouTube there are some "Tau au Tac" shows that have Giraud, Hugo Pratt and Steranko drawing live. It’s fascinating to watch them thinking visually:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=do-cvwBKfw8&noredirect=1

It’s a particular joy to watch Pratt as he draws Corto Maltese behind the lettering across the top of the panel.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Baldo, Hector Cantu and Carlos Castellanos’

comic strip about a Latino family with an emphasis on the eponymous teenager,

ventured into the disputation about illegal immigrants during the last week in

October. As you can see here at your elbow, the strips focused on Baldo’s young

sister Gracie and her friend Nora. The week ended with Gracie back home, confiding to her father that the kids at school have been taunting her with “illegal”accusations. He’s alarmed, even aghast, but he reassures her by saying: “Gracie, we have nothing to worry about. You’re safe here in our home. You, too, Nora.” It’s a pat response. Too pat. And all of us know—as Cantu surely expects us to by offering so lame a resolution to the problem—that no one with a Latino name or complexion is safe at home. Or anywhere else anymore.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. Verbatim Quotation Borowitz Report by Andy Borowitz A looming presidential race between a black guy and a Mormon is creating a major quandary for America’s bigots, a new poll reveals. According to the poll, conducted by the University of Minnesota’s Opinion Research Institute, a broad majority of likely bigot voters “strongly agreed” with the statement, “If it winds up being between a black guy and a Mormon I don’t know what I’ll do because I don’t know which I hate more.” Tea Party activist Eldin Brazelton of Oak Park, Illinois, expressed a frustration typical of the bigots surveyed: “We’ve spent the last three years stirring up anger towards a black guy, and that’s all going to go to waste if we just up and nominate a Mormon.” According to Mr. Brazleton, a presidential choice between President Barack Obama and former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney would be no choice at all: “For the life of me I don’t know why we can’t just have a regular President.” Mr. Brazleton, who considers himself a sexist as well as a bigot, said that the doomsday scenario unfolding for 2012 offered one small silver lining: “At least we know it’s not going to be a woman this time.” Elsewhere, in response to the ongoing Occupy Wall Street protests in lower Manhattan, banking giant Goldman Sachs announced today that it was investing in pepper-spray futures.

FROM THE SUBLIME TO THE IDIOTIC A documentary entitled “Wham! Bam! Islam!” that aired October 13 on PBS examined the fate and fortunes of The 99, a comic book team of Muslim superheroes who exemplify the 99 attributes of Allah, concocted by a Columbia University educated Kuwati psychologist. A pumpkin weighing 1,661 pounds took top honors at a New England regional contest but fell 150 pounds shy of the world’s record, set last year in Wisconsin. Meanwhile, the U.S. Senate, which has stalled most legislation of significance these last couple years, continued its effort to stymie every Obama initiative: this time, it came out in favor of potatoes by blocking an Obama proposal to reduce starchy foods in school cafeterias by limiting lunchrooms to two servings a week. In Seattle, a member of the Rain City Superhero Movement, a group of masked crime-fighters who patrol the streets of the city, was arrested for assault after he allegedly pepper-sprayed a group of people outside a nightclub, saying he was breaking up a fight. But police said he started the fray. He goes by the name Phoenix Jones. In the Phillippines, Herbert Chavez has been having plastic surgery done for more than a decade, seeking to make himself look like Superman. Chavez, a fashion designer by trade, has had his skin lightened, a cleft put in his chin, and additional work on his nose, cheeks, lips and thighs. Next he plans to have metal rods inserted into his legs to make him taller; he’s 5-foot seven-inches at present. “Anyone can become a superhero,” he says. Harold Camping’s latest prediction of the end of the world was another dud. After the failure last May 21, he revised his calculations and settled on October 21 at 5:59 p.m. But you’ll notice we’re still here. And, more importantly, so is Camping. His notion is that all good Christians should have been raptured into heaven, leaving only sinners behind. So either he was wrong again, or he’s as much a sinner as thee and me, aristotle. Or he could just be a nut. A source familiar with the 89-year-old prophet says he’s made this prediction at least twelve times, the first in 1978.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE “Even if you are on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.”—Will Rogers “When we remember we are all mad, the mysteries disappear and life stands explained.”—Mark Twain “Life is not a spectacle or a feast; it is a predicament.”—George Santayana Not for Charles Baudelaire, who said: “Life is a hospital in which every patient is possessed by the desire of changing his bed. One would prefer to suffer near the fire, and another is certain he would get well if he were by the window.” “It’s not the consumers’ job to know what they want.”—Steve Jobs

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

THE BIG NEW FIVE-TWO. ICv2.com relays the report from DC Comics that its “New 52" dodge is not only an unqualified success but nearly unprecedented. Since the new line’s introduction in early September, over 5 million of its “new” funnybooks have been sold, stimulating an erstwhile stagnant market. “DC officials say sales are the highest in 20 years,” quoth Bella English at the Boston Globe.. Justice League No.1, the curtain-raiser, is in its fourth reprinting, having sold more than 250,000 copies. DC also says that Batman No.1 and Action Comics No.1 each sold over 200,000, and Detective Comics No.1, The Flash No.1, Green Lantern No.1, and Superman No.1 all sold over 150,000 copies. Most of the other titles have posted sales in excess of 100,000 copies. Sales figures include the UK and other countries, not just the U.S., quoth ICv2.com. One aspect of the revamp scam involved hopes for digital sales, and John Rood, DC’s Executive VP of Sales, Marketing, and Business Development, claims that’s going well, too: “Our digital sales have been better than we could imagined and we are pleased that these sales are additive to traditional publishing sales in the comic shops. We are not migrating readers from paper to digital. We’re adding new readers to the mix.” Well, I’m not so sure about that last part—adding new readers to the mix. Digital readers? How many, exactly?

WHAT’S BROUGHT ON THIS REMARKABLE SUCCESS? At first blush, it would seem to be the New 52's frenetic deployment of sex and violence. Bella English rang the alarm bell: “Lois Lane shacking up? Superman graphically tortured in an electric chair? Batman and Catwoman having sex on a roof?” The changes aren't pleasing everyone, she continues: “The blogosphere is abuzz with complaints about the extreme violence, hypersexualized women, and bad language in the new issues—the sorts of things that the Superman of yore would have swooped in to conquer, never countenanced. Long considered family entertainment, superheroes over the years have become darker and racier, geared more toward young adults than youths. Though the superhero make-overs aren't as raw as some of the others DC has reissued—Voodoo, for instance, seems like soft porn—the content is nonetheless aimed at a more mature readership than ever.” More mature? Or just older and suffering from arrested development. DC Comics co-publishers Jim Lee and Dan DiDio issued a statement explaining the motive in devising the New 52: “Comic book sales have been slipping in recent years, and we needed to make changes. We needed to energize our existing fan base, reconnect with lapsed readers, and introduce our storytelling to people who know our characters from films and tv but have never read a comic book.'' Admirably succinct. And there were nuances, too. The idea was to revamp the line-up, outfitting Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Flash, Green Lantern, Aquaman and others for life in the 21st century. Their costumes and personalities were to be tinkered with to reflect today's real-world themes and events, to streamline continuity (presumably to discard pesky fragments of the characters’ fictional biographies that had become too complicated to deal with on a recurring basis). Geoff Johns, who writes the Justice League title, said he’d focus on the “interpersonal relationships” within DC’s trademark superteam: “What’s the human aspect behind all these characters? That’s what I want to explore,” he said. "We really want to inject new life in our characters and line," DiDio told Brian Truitt at USA Today. "This was a chance to start, not at the beginning, but at a point where our characters are younger and the stories are being told for today's audience." The sales numbers, for the time being, are more than merely good—which justifies a lot of mischief and good intentions. But how, exactly, has the New 52 altered the DC Universe? Or has it? I decided in August, before there was any blogobuzz, to see how DC would revamp its most durable characters. I haven’t read all of the New 52: I chose only the books about the traditional DC characters—Superman, the Batman entourage, Wonder Woman, Blackhawk. Plus a smattering of others. But mostly, the old timey champions that I’d doted on when a mere callow youth several centuries ago. And I started with the curtain-raiser.

Justice League. Drawn by Jim Lee, the visuals are often as confusing as Geoff Johns’ story. Lots of graphic razzle-dazzle, a jumble of lines and a torrent of color, explosions on every other page, close-ups so close that they do not reveal enough for us to know what they are depicting, long shots of helicopters on an unspecified mission in which our protagonists are drawn too small to distinguish. Johns, like most funnybook writers these days, thinks he’s writing for a motion picture—quick cuts, close-ups, mysteriousness, all of which is explained in a movie by heaping up squibs of exposition en route, so to speak, and before you leave the theater, you get the whole picture. If practiced in a comic book, too much of the exposition is necessarily delayed until the next issue. The general plot here seems to be that Batman is trying to overpower a BEM intent on planting a bomb. He explains this on the 13th page. Until then, all we have is the battle with the BEM, hovering helicopters and churning blades, angry armies of police, and, suddenly, the appearance of the Green Lantern, whereupon the entire story devolves into a pissing contest between Batman and GL. GL is arrogant; Batman is ingenious. And then Superman shows up and bops GL into next Sunday, thereby undermining somewhat GL’s good opinion of himself. All of which takes place “five years ago,” according to a caption on the first page; in the “present” (i.e., five years “later”), superheroes are apparently regarded as criminals because no one knows there are superheroes. In other words, the entire issue is a flashback. And I’m not sure even “five years ago” that the superheroes knew they were superheroes: judging from the rampant mutual hostility on display, they seem more like juvenile delinquent gang members. GL takes Batman from Gotham to Metropolis to meet (or perhaps to overpower) Superman, and while they are en route, we find ourselves suddenly on a highschool or college football field where an African American called Vic is distinguishing himself. This sequence is so off-topic as to be thoroughly intrusive. My first time through this book (I had to read it three times to make as much sense of it as I’ve conveyed herein) (if any), I thought this 4-page digression was a preview for another title. I still don’t know the relevance of “Vic.” This is terribly dense writing, kimo sabe. And terribly confusing. I don’t read a lot of superhero titles these days: I tend to jump in whenever I see a write-up in Previews that piques my interest—or I pick up a title at the comicbook shop because the artwork is attractive. In other words, I’m probably the “lapsed reader” that Lee and DiDio hope to re-engage with the New 52. Sorry, guys: it’s not working. At least, the visual and plot maelstrom of Justice League hasn’t sucked me in. Two speeches, however, brought a smile to these aged and chapped lips. In the universe of the New 52, Green Lantern doesn’t yet know Batman, so when he meets the Cowled Crusader, he asks him what his powers are. Can he fly? Nope. Does he have super-strength. Nope. “Hold on a second,” GL says, “—you’re not just some guy in a bat costume are you? Are you freaking kidding me?!” And then, when the two arrive in Metropolis and disembark GL’s emerald green and glowing ring-construct of an airplane, Batman complains about how conspicuous their arrival is, landing in a glowing green jet. To which GL reposits: “You can’t fly, so how else were we going to get here? Talk in a deep voice?” Talk in a deep voice. What a hoot. At the comicbook shop I frequent, one of the owners, who pays more attention to superhero comics than I do, explained that the rivalry between Batman and Green Lantern has been going on for some time, so because this first issue of Justice League captures that essence, it’s a good jumping in place for lapsed readers. Well, maybe. Still, that reeks of the kind of convoluted continuity that I thought the New 52 was going to sideline for a while. And who’s Vic anyhow? That seems a scrap of continuity that is beyond comprehension in this issue. I’m not sold. Not with this title. I doubt I’ll be coming back for more. But with Action, I might be.

Action. Herein, at least, the pictures are revealing: we can tell who is being depicted and what the action is. At least, no mind-blowing explosions in the opening sequence; and when the visuals go berserk, we’re at the end of the book, by which time, we’re a little better oriented to what’s happening herein and can therefore make sense of the pictures. The book’s cover is a visual evocation of Superman’s comic book past. Rags Morales, who drew this issue and its cover, explains in the “Inside the Action” feature of No. 2: “For the first twenty years, flying with that pose I gave him on the first cover—the one bent leg and the one straight leg, and the counterbalancing with the arms—was the Superman trademark, and it made him look like he was running [through the air]. Here I am trying to do an homage to it. It brought it back to the essence of that character.” The essence of the historic Superman is that he rescues people in trouble, and this book is full of that sort of action: he rescues people who are trapped in a building being demolished by wrecking ball; and he rescues the passengers (including Lois Lane and Jimmy Olson) in a runaway sabotaged commuter train. Said Grant Morrison, who wrote this issue: “I constantly put Superman up against very physical objects: a wrecking ball, a tank, a train, solid stone. It was designed for the motion of that muscular, 1938 Superman—to really tie him into physical things, to big, heavy objects. ... The physical things Superman does came from the first year of Action Comics, where they were doing this nonstop, kinetic, muscular action. I wanted to get that into the actual form and structure of this whole run, that feeling of motion and action. It’s called Action Comics—let’s do that!” But before Superman starts rescuing people, he does the other thing that earned him renown: he takes out a passel of bad guys—namely, a corrupt politician (or some other variety of bigwig; can’t tell for sure and it doesn’t matter). In the book’s opening sequence, he overpowers the guy’s bodyguards and then gets him to confess his evil deeds by dropping him from a tall building (but going down with him and catching him so he won’t be smashed when he hits the bottom). This sort of derring do attracts the attention of the city’s police, who, naturally, are somewhat opposed to vigilante endeavors. But Superman escapes: he’s too fast and too invulnerable for the pursuing posse. Visually, the opening pages feature a man battling other men, Superman vs the bad guys, all easily recognizable forms and functions. No BEMs and explosions. By the time we get to more complicated action, we’re tuned in and know what we’re watching (a progress that is completely, and bafflingly, reversed in Justice League, which, as I said, starts in medias res and explains afterwards). Action’s Superman is not the same Superman who decks Green Lantern in Justice League. He’s manifestly younger and displays a fun-loving side. And he’s not wearing the “new costume” he’s got on in Justice League. Instead, his wardrobe is right off the Smallville farm: he’s wearing jeans, clodhopper shoes, and a Muscle Beach t-shirt emblazoned with the usual emblem. And a cape. The cape will later figure importantly in the plot as Morrison explains (maybe in Action Comics No. 3?) how it came to be. After the first round of physical action, we come upon a quiet page that shows Superman getting out of uniform (he takes the cape off and wads it up and tucks it into his jeans pocket) and donning a baggy shirt (that hides his muscles, saith Morales). Ingeniously, Morales realizes that the eyeglasses Clark Kent wears are thick enough to “distort the size of his eyes and make them seem larger.” Morrison applauds: “His eyes get bigger so he looks more like a kid. That’s why Rags is so good to work with—he really thinks about this stuff, and it makes such a big difference to the finished product. When I saw [Rags’] Clark Kent, it changed the way I wrote the character. He suddenly seemed very young, and he could be a little big brattish. Clark’s obviously this little hardcore farmer’s boy who’s not taking any crap from anyone.” The first issue also introduces an alteration in the Superman mythos: Lois Lane is the daughter of a general in the Army, Samuel Lane. “She’s an army girl,” says Morrison, “but she’s become a crusading journalist to annoy her parents.” Nasty ol’ Lex Luthor shows up: he’s apparently in charge of some aspect of the Army’s “security” apparatus, and he views Superman as an alien organism about to infect the planet and upset its ecosystem, so he wants to examine the “creature” to find out what makes it tick and how to destroy it. This incarnation of Superman has eyeballs that turn red and glowing when he gets angry or when he’s using the numerous powers that his eyes are capable of. Red glowing eyeballs are a little disturbing, but not as puzzling as two other elements Morrison introduces: Superman gets scratches on his face during the wrecking ball rumpus, and when he’s stopping the high-speed train, he starts bleeding from the ears. I thought Superman was invulnerable and impervious to physical damage. Evidently, not so, not any more. Morales’ storytelling is deft and dramatic. Action sequences are fast-paced, alternating long shots to show what’s happening with close-ups to reveal the effects of the action on Superman and others. The conclusion of the runaway train episode is particularly impressive, alternating pictures showing how people are reacting to the wreck in progress with pictures that show the progress of the wreck as Superman tries to stop the train by leaning into its bullet-shaped nose at the front, exerting his physical power against the momentum of the runaway. And it ends when the train at last comes to a stop, its nose pinning Superman to a concrete wall. Said Morrison: “When he’s hit by the train, he’s not the Superman we’ve seen for the last 25-30 years. This is someone who can be hurt. I wanted to show he has limits. But it’s also this up-front connection to the Superman legend—he’s actually punched in the chest by the ‘speeding bullet.’” In short, this first issue is a promising one. It engenders a sense of wonder as well as excitement, and it does it without brutality, rampant sex, or nudity. That changes a little in No. 2. The opening sequence in this issue has Superman bound to an electric chair and subjected to increasingly more powerful electric shocks. Luthor took possession of Superman when the latter was pinioned to the wall by the speeding bullet train, and now Luthor wants to know just how indestructible Superman is, and he’s thinking about dosing him with a powerful acid to see how his skin reacts. Superman’s mouth is trickling blood at the corners, but his damaged tissue is repairing itself as we watch. A different Superman indeed. Superman soon breaks loose—frying all of Luthor’s restraining equipment with his x-ray vision—and then he wrecks Luthor’s chamber of horrors and escapes, retrieving his cape (which Luthor was also experimenting with) on his way. The escape sequence, in which Superman eludes his captors effortlessly, despite their armament and weaponry, and emerges apparently unscathed by Luthor’s experiments, is a satisfying conclusion to the issue—Superman triumphant, Luthor baffled and foiled. The only blemish—an awful rendering of Superman’s face as he leaves in an elevator. As a lapsed reader, I’m hooked. The first issue is contaminated with no continuity entanglements that interfere with an enjoyable read, and the action is fun to watch. The Superman title, on the other hand, are something of an other else altogether.

Superman. Here the Man of Steel is a mature superhero not a young man becoming a superhero as he is in Action Comics. Bella English summarizes the issue: “The Daily Planet has been sold to a tabloid newspaper company with a reputation for illegal wiretaps and lies. Lois Lane is placed in charge of new media, but mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent resents the takeover. Later in the first issue, he drops in on Lois at home, only to find her with a half-naked guy. Downcast, Clark says goodbye and leaves. The story ends with Lois telling her overnight guest: ‘Shut up and get back in bed!’'' Yet to be explained: how, exactly, did Superman graduate from the farmboy to the savior from Krypton? What’s the narrative bridge from Action Comics to Superman? References in this issue to the death of print media and the unethical machinations of tabloid journalism “reflect today’s real world events and themes,” and writer George Perez guides us expertly through the maze of personal relationships infesting the title—Lois and her former boss Perry White and her new boss Morgan Edge as well as her competitive posture towards Clark—and builds suspense between print news media and the Internet’s visual digital coverage. This is a lot to swallow at one sitting, and Perez, who did the breakdowns, resorts to the devices he has skillfully employed for years—lots of panels crowded with tiny pictures. The visuals are not so much exciting as they are complex and therefore not engaging. Superman in this title has graduated away from Action Comics’ Muscle Beach t-shirt and jeans. Herein, he wears what, at first glance, seems to be a species of body armor. For an invulnerable character? But the suit isn’t armor. Nor is it quite as seamlessly skin-tight as the previous generations of spandex. Careful inspection shows that it, like Batman’s garb, is made of pieces of heavy cloth stitched together in a way that leaves massive seams. And the pieces seem tailored to fit individual muscles. If it isn’t body armor, it’s the nearest thing. DC is readying its ensemble for the movies: in Hollywood, they’ve discovered that actors generally don’t have the physique for superheroing, so the inventors of all those movies put their actors in body armor that is molded into six-pack abs and bulging biceps (not to mention, in an earlier Batman flick, nippless). Or, alternatively, the actors wear heavy cloth longjohns the industrial strength seams of which mask the absence of six-pack abs and bulging biceps. Complicated visuals are not the only shortcoming in this issue. The central event—the invasion of an alien fireball, threatening to consume Metropolis—has cliche writ large all over it. Moreover, pictures of a tiny Superman blowing cold air on a giant fireball are not visually interesting. Fireballs make spectacular visuals, and Jesus Merino does a credible job making repeated appearances of a flaming sky look different in successive panels, but pretty pictures are not the whole game in comics storytelling. Perez heightens the excitement by alternating fireball sequences with scenes in the newsroom with Lois directing coverage of the event. Skillfully done but, again, a flood of small panels jammed with miniature people. Throughout the book, the pages seem overpopulated, crammed with visual information. A little off-putting. The last scenes in the book, wherein Lois comes to the door of her apartment in answer to Clark’s knock—and she’s accompanied by her half-naked lover of the moment—are, in contrast to what’s gone before, visually stark. And as a result, they are more effective: they have more narrative impact. A good thing in an emotionally wrenching sequence. But is coitus the only way DC’s writers have of engaging us emotionally? No: there’s also gruesome horror, which we get in Detective.

Detective. In the New 52 version of the title that introduced us to the Cowled Crusader in May 1939, we find Batman in pursuit of the Joker, who is off on a fresh killing spree. The issue is written and drawn by Tony Salvador Daniel, who has a penchant for the cinematic technique of quick-cutting from one close-up to another, a strategy that is sometimes effective and sometimes confusing. In the opening sequence, for instance, we get a series of close-ups of the Joker’s insanely bulging eye; then the camera backs away enough a few pages later to reveal that he’s choking someone. But you must examine the pictures carefully to realize that the Joker is naked—a realization that dawns only later in the book, when Batman mutters to himself: “I’m trying to figure out what the Joker was doing naked—does he always remove his clothes first?” First—before killing, we suppose. But no explanation for the Joker’s nudity is forthcoming. If the New 52 is supposed to hit the re-set button for the DC Universe, there seems to be no Ctrl-Alt-Delete here: Batman is the same Batman we’ve had since Frank Miller’s Dark Knight debuted. In a few panels en passant, Daniel adroitly re-establishes the essential elements of the traditional mythos—Batman is a brooding, vengeful vigilante who may, as he says, control the night, but he’s also a target for the forces of law and order even while being Commissioner Gordon’s vital cohort in battling Gotham’s criminal element. We visit the Batcave and meet the ever-faithful Alfred, who reminds Bruce Wayne that he’s stood up his date for the evening. By the end of this issue, Batman has captured the Joker after a spectacular 5-page struggle deftly visualized by Daniel, who, here, resorts to alternating long-shots and close-ups, thereby depicting the action and its effects on the actors with dramatic impact. Then we’re in the Joker’s cell where the Dollmaker satisfies the Clown’s fiendish desire by taking a sharp knife and peeling off the psycho’s face and nailing it to the cell’s wall. Without a doubt, that’s the most bloodcurdling of the New 52's plot developments, equaled, perhaps—but just in the shock to conventional morality—only by Catwoman’s penthouse sexual assault on the Dark Knight in Catwoman No. 1.

Catwoman. No.1 begins with Selina Kyle dressing in a hurry, various of her ample attributes glimpsed as she does, and when she’s fully dressed in costume, those attributes are on impressive display: her black leather battle gear is designed to reveal her figure in nearly naked detail with glistening bosom and buttocks brilliantly highlighted. She escapes a meaningless break-in at her apartment which is promptly blown up by the explosive the interlopers set off, and then she infiltrates a Russian mob party and overhears a plot to steal a painting. While at the party, she sees a bad guy she hates, so she follows him into the men’s room, unveils her chest, and, his guard momentarily dropped, she beats him up and gouges out one of his eyes. Then she has to fight her way out of the party because the bartender she chloroformed wakes up and blows her cover. She’s recuperating at a penthouse suite she’s squatting in when Batman shows up, expressing concern about the bombing at her apartment. Without saying a word, she throws herself at him, and they enjoy a few moments of carnal conviviality, during which she says to herself, breathing hard and gasping all the while: "This isn't the first time. Usually it's because I want him. Tonight I think it's because I need him. Every time ... he protests. Then ... gives in. And he seems ... angry. But that doesn't slow either of us down. Still ... it doesn't take long ... and most of the costumes stay on.” It doesn’t take long? What kind of sex is this? Certainly not the loving sort. This is the kind of sex that links sex with violence. This is the sex of conquest. And sex, if we are to judge from this issue and the next, is the focus of the new Catwoman: the next issue’s episode is entitled “The Morning After.” The title of this issue’s episode is “... and Most of the Costumes Stay On ...” The 4-page fornication sequence is undoubtedly the most expert portrayal of sex in costume that modern funnybooks offer: focusing on hands and body parts, it captures the excitement of lust and its gratification without being visually genital. The episode may not be “nice” by the standards of conventional (albeit outdated) morality, but it’s nicely done. No. 2 gives the lie to No.1's slogan, by the way: in the opening scene, it’s clear that while most of Batman’s costume stays on, most of Catwoman’s costume is off and her bra is undone. In her running interior monologue through the first issue, Catwoman revels in the excitement of danger: “I’m not sure I like doing anything unless it puts me out on the limb. ’Cuz that’s where the fruit is, right?” Catwoman is clearly a character with bizarre compulsions, and writer Judd Winick carries it all off with aplomb and dispatch, aided and enhanced by Guillem March’s stunning pictures. March is good with facial expressions—getting a variety laminated onto Selina’s visage without losing an iota of her facial beauty—and expert at voluptuous female figure drawing, on continuous display in every fight sequence into which Catwoman so eagerly throws herself. And the storytelling here is visually spectacular as well as dramatically engaging. If the first issues of the New 52 are setting the mold for each title, this title is going to be about sex and violence. Batgirl, on the other hand, is simply silly.