|

||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 261 (May 6, 2010). We seem to have degenerated into a monthly magazine, but the quantity, we trust, will make up for being less frequent. Hopping down the bunny trail this time, we celebrate the Schulz heirs getting a hunk of the licensing rights to Peanuts, view with alarm the phoney excitement over cartooning Muhammad on “South Park,” rejoice (at great length) in Archie Comics’ increased aggressiveness in the marketplace of modernity (and their persistent promotion of their product with newsstories about Archie’s new married series and the arrival in Riverdale of a gay classmate), and perform an exhaustive review of Ted Rall’s Year of Loving Dangerously graphic memoir. We also review first issues of Turf, Black Widow, and Kill Shakespeare, herald Hef’s saving of Hollywood, and examine the history of Palestine and our news media’s failure to be objective about it. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department: NOUS R US Penny Arcade in Time’s 100 Influential Schulz Heirs Get Rights to Charlie and the Gang Muhammad in South Park “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day” Debuts but Fizzles The Other Muslim Cartoon Controversy More Editorial Cartoon Awards Frazetta Flap Folds Hef Saves Hollywood ARCHIE COMICS GETS AGGRESSIVE Archie Still Married to Betty and Veronica Gay Guy Moves in to Riverdale amid Much Fussin’ New CEO Enthuses in All Directions EDITOONERY AAEC Pitches Freedom of Speech to Apple Mike Luckovich’s Delightful Pranks BOOK MARQUEE The Knight Life: Chivalry Ain’t Dead Dan DeCarlo’s Jetta GRAPHIC NOVEL The Year of Loving Dangerously What’s Next from Ted Rall FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Turf Black Widow Kill Shakespeare Bob Hall’s The Bruce The Bard’s Immortality Defended The Mess-o-patomia And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits “Iron Man 2" is scheduled to open May 7, Friday. And to commemorate the occasion,

we’ve affixed here the Special Poster that USA Weekend commissioned and published

two weekends ago, drawn, mostly, by John Romita, Jr. Time published its annual “100" issue, dated May 10, alleging that the 100

persons listed are “the most influential people in the world.” The usual suspects line up

on the cover—Bill Clinton, Steve Jobs, Sarathan Livingston Palin—and, inside, such

undeniably August personages as Glenn Beck, Lady Gaga, and Conan O’Brien as well

as numerous people from all around the globe whom I’d never heard of (but no one, I

ween, the equal of Glenn Beck or Lady Gaga: apparently only in this country are such

people influential). I was mildly surprised to find Scott Brown listed—how much

influence can a freshman senator have?—but I was glad to see cartooning represented.

The representatives are Jerry Holkins and Mike Krahulik, the creators and proprietors

of the online comic, Penny Arcade. The accolade seems perhaps a little grandiose until

we read editor Richard Stengel’s explanation for “Time 100": this issue of the magazine,

he said, is “not about the influence of power but the power of influence. ... We sought

out people those ideas and actions are revolutionizing their fields and transforming

lives.” Penny Arcade, I assume, reflects the fate of comics, hence Holkins’ and

Krahulik’s place on the listing: they’ve been plugging away at digital cartooning more

successfully and longer than most of their online cohorts, implying by their tenure and

achievement the future of the medium. The drawing skill manifest at Penny Arcade is

also much better these days than it was at the beginning. Is Krahulik still drawing it?

Hope so: that means we can all improve. Nice photograph of the duo, by the way:

Holkins hidden and peering, somewhat furtively, over Krahulik’s shoulder. And now we come to a record of sorts: in his 9 Chickweed Lane strip, Brooke McEldowney has been telling a continuing story about Edda’s grandmother’s World War II romance since early November 2009. And the story is still unfolding. That’s six months and counting. No continuity strip in recent times has performed a stunt like this. Most syndicates insist that their continuity strips (Judge Parker, Mary Worth, Rex Morgan, Spider-Man, and a few others) regale us with stories no longer than, say, six weeks. Bravo, Brooke. Not only is your story long, but it’s fascinating.

SCHULZ HEIRS, THANKS TO SCRIPPS’ CORPORATE GREED, GET WHAT EVADED SPARKY ALL HIS LIFE The headlines were just a tad alarming: “Peanuts Sold,” they exclaimed in one variation or another. (“Snoopy Sold” being another version.) Burrowing down into the newsstories, however, we found the situation a little less panicky. Iconix Brand Group is indeed buying licensing rights to the characters of the famed comic strip—80 percent of them, that is; the heirs of the late cartoonist/creator Charles Schulz will own 20 percent of those rights, which is more than even Schulz owned. He, like most syndicated cartoonists of his generation, gave up rights to the strip when United Feature Syndicate contracted with him to distribute it. All these years, UFS has owned Peanuts; Schulz owned nothing. E.W. Scripps, which owns UFS and United Media, a sister syndicate, has been hankering to get out of the newspaper business and acquire financial resources that it can invest in niche cable-tv and online ventures. To that end, Scripps has been “exploring strategic options” for United Media Licensing since early February. One of those options was to sell the licensing arm. It’s not altogether clear that Iconix didn’t buy the whole enchilada, including Peanuts; most newsstories mention other character “brands”—Dilbert and Fancy Nancy, Raggedy Ann and Andy and other characters—that Iconix acquired the licensing rights to when it, and the Schulz family, paid Scripps $175 million (just about enough to replenish Scripps’ coffers after its $181 purchase of the Travel Channel six months ago). Presumably the Schulz family wasn’t interested in any pieces of Dilbert and paid their share of the purchase price only for Peanuts rights. The Associate Press reported that Scripps sold United Media Licensing, the whole thing. But the distribution and sale of comic strips will still be accomplished by UFS. The syndicate, in other words, is still in business: only the licensing rights have been sold. Iconix, which halted talks to buy Playboy Enterprises Inc. in December, may do "a big deal with one of the big retailers" over the Peanuts license, according to Iconix chair and CEO Neil Cole. Other opportunities may be found in video games and emerging markets such as India, he said. About two-thirds of Peanuts sales come from outside the U.S., Iconix told Andrea Snyder and Lauren Coleman-Lochner at Bloomberg News. Following Schulz's wishes, no new Peanuts strips will be drawn, according to the website of the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California. The Schulz family, which didn’t own the brand but, in partnership with UML, managed licensing through Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates, will work closely with Iconix, Cole said: "We're going to be partners and they're going to be very involved.” The Iconix deal will end a 60-year relationship between United Media and the Schulz family. Peanuts, with its cast of Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Lucy and the gang, is licensed in more than 40 countries and generates annual retail sales of more than $2 billion, by far the biggest single hunk of UML’s revenues. Said Craig Schulz, son of the late cartoonist: "Peanuts now has the best of both worlds, family ownership and the vision and resources of Iconix to perpetuate what my father created throughout the next century with all the goodwill his lovable characters bring," ***** IN A REVIEW of My Life with Charlie Brown, a collection of Charles Schulz’s major writing (which we reviewed here last time, Opus 260), James Rosen of the Washington Post Writers Group speculates that the “impetus for the book, published with the cooperation of the Schulz estate, appears to be his family’s well-publicized disappointment with ... David Michaelis’ SCHULZ and Peanuts biography.” Well, maybe. I asked Tom Inge, who edited My Life, about the genesis of the book, and he wrote back: “Actually I proposed to Jeannie Schulz putting this book together shortly after Sparky’s death, but she was high on Michaelis at that time and did not want to do anything that might take attention away from the biography. Michaelis himself liked the project and did not see it as interference but rather a help to him. In any case, I put it on the back burner until the dust settled after the biography. So I did not do it in direct response to Michaelis, but it seemed to work out that way.” Inge, the Blackwell Professor of Humanities at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia, enjoyed a long friendship with Schulz, visiting him occasionally to talk about comic art and Inge’s numerous comics research projects. Their relationship began when Peanuts was only five years old and Inge wrote to Schulz asking the cartoonist to draw an illustration for his college’s freshman handbook; Schulz gladly drew a picture for Inge. Inge elaborated in response to some questions from Hogan’s Alley: “Cartoonists frequently complied with such requests in those simpler days long before fandom and quick ebay sales came on the scene. It wasn’t until much later that we reestablished contact after I had begun to write about comic art and was invited to contribute an essay on Peanuts to the catalog for an exhibition of his original art. He liked the fact that a Professor of English considered his work important, and I would visit him from time to time in Santa Rosa. He was an avid reader, especially of contemporary literature, so we often talked at cross purposes. That is, he wanted to talk about literature, while I wanted to talk about comic art. “Over the years,” Inge continued, “I took notice of his essays and articles contributed to magazines, newspapers, and anthologies of his comic strips, and I thought they were remarkably insightful and well written. I put them away in a file with the intent of assembling them into a book someday primarily for scholars and lovers of the comic arts. I wanted them to be available on a library shelf for future readers alongside the collections of Peanuts as a way of shedding light on his accomplishment.” The Schulz estate and Jeannie Schulz approved the project that resulted in the present volume, and Inge was allowed access to the cartoonist’s papers at the Schulz Museum and Research Center where several unpublished manuscripts were found. “While a few additional pieces have surfaced since then,” Inge said, “the book pretty much contains all of his important writings.” Asked if he found anything Schulz said or wrote to be surprising, Inge replied: “I was somewhat surprised by his blunt statements of belief while he was in his theological period, studying the Bible and commentaries, and teaching Sunday school. Of course this was a passing phase as he moved towards what he would later describe as ‘secular humanism.’ He was a lay theologian in effect who thought through matters of faith very carefully, and his philosophic concerns about the human condition are clearly reflected in the comic strip. He was basically an existentialist, although he often pretended to be puzzled by that designation.” In short, the book wasn’t intended as a corrective to Michaelis’ skewed biography of Schulz: it may serve that purpose, but more than that, it was Inge’s act of affection and regard for the cartoonist. TEMPEST IN A TEACUP: MUHAMMAD GOES SOUTH Or Vice Versa The Prophet Muhammad has emerged as Western Civilization’s surest bet in any campaign to drum up attention. Every other week, we encounter newly sprung freshets of terror and intimidation in reports about Scandinavian cartoonists shutting themselves away in bomb shelters against the possibility that their habitations will be stormed by Islamic hooligans. The threats, if we judge from the Danish Dozen that inspired riots and killings in the Muslim world and elsewhere in 2006, are real enough. But news about them has acquired some of the trappings of publicity agentry. Most recently, it was the “South Park” boys, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, who concocted an episode of their famously irreverent tv animation that attracted the salivating newshounds. Here, with some help from David Itzkoff at the New York Times, is what happened. On April 14 Comedy Central broadcast the 200th episode of “South Park,”which, in honor of the occasion, was populated with nearly all the famous people the show has lampooned in its history, including celebrities like Tom Cruise and Barbra Streisand, as well as major religious figures, like Moses, Jesus and Buddha. Because any depiction of Muhammad since 2006 is likely to send Islamic hooligans into one of their frenzied froths, Stone and Parker showed their characters agonizing over how to bring Muhammad to their fictional Colorado town. At first the character said to be Muhammad is confined to a U-Haul trailer, and is heard speaking but is not shown. Later in the episode the character is let out of the trailer, and he is seen dressed in a bear costume. Well, that, presumably, was too much. The revered Prophet in a bear costume! The next day a nearly non-existent group calling itself the Revolution Muslim posted a message on its website, asserting that the previous night’s installment of “South Park” had “insulted the Prophet, adding: “We have to warn Matt and Trey that what they are doing is stupid, and they will probably wind up like Theo van Gogh for airing this show. This is not a threat, but a warning of the reality of what will likely happen to them.” Van Gogh, a Dutch filmmaker and a critic of religions including Islam, was murdered by an Islamic thug in Amsterdam in 2004 after he made a film that discussed the abuse of Muslim women in some Islamic societies. The Revolution Muslim’s protests to the contrary notwithstanding, the April 15 posting was pretty clearly a threat, not a warning. Nor is it just a helpful prediction of what the ragtag Revolution Muslim outfit thinks will happen—all out of their control, of course. AP’s David Bauder reported that the posting included a gruesome picture of Van Gogh and the addresses of Comedy Central's New York office and the California production studio where "South Park" is made. In short, it looked suspiciously like the Revolution Muslim gaggle (or, as Kathleen Parker put it, “12 guys and a website”) is giving directions to Muslim hooligans who lurk, awaiting instructions for the commission of mayhem. At the New York Times, Clyde Haberman took the threat seriously: “Let’s see. A mobster warns that you will wind up like Paul Castellano, the crime boss who was gunned down outside a midtown steakhouse in 1985. Maybe the guy is merely a blowhard. But maybe he is a sociopath. You’re not really sure. Either way, you’ve been handed a death threat.” Or maybe not. But with Islamic hooligans, it’s better not to speculate. “Unfortunately,” Haberman said, “recent history is studded with episodes in which extremists resorted to murder because they felt that Islam had been wronged.” Despite the threat, Parker and Stone included the Muhammad character again in the next week's episode, but this time, they exercised a measure of self-censorship: because Muslims are widely believed to object to representations of their prophet (not entirely true, as we’ve pointed out previously), “Muhammad” appeared with his body obscured by a black box with the word “Censored” on it, and whenever the presumed Muhammad character’s name was mentioned, an audio bleep was substituted for it. But it was all just one of “South Park’s” colossal jokes: when the bear costume was removed, the personage inside was not the Prophet: it was Santa Claus. But Comedy Central was not amused. Maybe because Santa Claus is another religious icon. Before airing the episode, Comedy Central took a few timorous precautions, injecting several more bleeps, some that obliterated Kyle’s final speech, which was about intimidation and fear. “It didn’t mention Muhammad at all but it got bleeped,” said Parker and Stone. Fearful and sufficiently intimidated, Comedy Central did not re-run the episode at midnight as it normally does, and it also failed to stream the episode on its website, where “South Park” usually appears after its broadcast. Those Santa Claus fanatics are murderous lunatics. Comedy Central didn’t always quake in fear. Itzkoff pointed to a July 2001 episode, “Super Best Friends,” in which Muhammad was depicted alongside the founders of other religions, including Krishna and Lao Tzu. But in 2006, when Parker and Stone wanted to weigh in on a controversy that erupted after that Danish newspaper published cartoons satirizing Muhammad, they were not given the same latitude: a character said to be Muhammad was concealed behind a large black box labeled “Censored.” “The measure,” Itzkoff said, “was taken by the ‘South Park’ producers partly at the insistence of Comedy Central, and partly as a commentary on the network’s policy of not allowing them to show the character, which the episode equated with giving in to the demands of extremists.” Parker and Stone displayed a perhaps surprising equanimity over this latest brouhaha, issuing a calmly phrased statement: “In the 14 years we’ve been doing ‘South Park’ we have never done a show that we couldn’t stand behind. We delivered our version of the show to Comedy Central, and they made a determination to alter the episode. ... We’ll be back next week with a whole new show about something completely different, and we’ll see what happens to it.” A couple years ago, Stone remarked about the irony of the situation: “It really is open season on Jesus,” he said. “We can do whatever we want to Jesus, and we have. We’ve had him say bad words. We’ve had him shoot a gun. We’ve had him kill people. We can do whatever we want. But Muhammad—we couldn’t even show a simple image.” In the Chicago Tribune, Ahmed Rehab, executive director of the Council of American-Islamic Relations in Chicago, wondered if the whole thing wasn’t “contrived.” Said Rehab: “The protagonists in the original controversy of 2005-06 consisted of a fairly mainstream Danish newspaper on one hand and mobs of angry, and sometimes violent, protesters on the other. The protagonists this time are a couple of jokesters who openly offend people for a living on one hand (“pushing more buttons than an elevator operator,” said Haberman), and a single posse of five ‘Muslims’ on the other (about whom we know very little) ... a group of literally 5-10 people who are widely reviled by the mainstream community for their radical and confrontational style, including harassing Muslims outside mosques (where they tend to be banned) with outlandishly provocative anti-American rhetoric. Most suspect the group is fraudulent. Its mysterious leader, born Joseph Cohen, is an American Jew who converted to Islam in 2000 after living in Israel and attending an orthodox rabbinical school there. Whether true Muslims or agent provocateurs, the result is the same: they are five community outcasts.” “Yet,” Rehab continued, “little to no context is given in the media when this group is mentioned, as if it were somewhat representative of a normative Muslim reaction. (They are a constant feature on CNN and FoxNews.) The real headline: most Muslims seem to have learned from the Danish episode. ‘South Park's’ provocation was mostly met by silence and indifference. The widespread Muslim attitude went something like this: this is a free country, you go on mocking Jesus and Muhammad, and we will go on keeping them in our prayers. No harm done. Muhammad's and Jesus' value to humanity certainly will not dip as a result of your mockery.” With most so-called news media in a raving, foaming-at-the-mouth tabloid mode, it’s impossible to know the actual facts about the matter, but I suspect Rehab is more right than wrong. Unhappily, the incident does not bode well for creative satirists. David Harsanyi, a columnist at the Denver Post, said: “If those who bankroll satirists can be so easily intimidated, shouldn’t we all be troubled about the lesson that sends religious fanatics elsewhere? And what does it say about us? ‘South Park’ might be offensive, but I assure you there would be few things more unpleasant than watching a cable lineup dictated by the members of Revolution Muslim.” The situation also attracted the attention of a Seattle bush league cartoonist

named Mollie Norris. Outraged at the continuing idiocy of stepping gingerly around

Muhammad because of the fulminations of Islamic hooligans, she resorted to her

Facebook page, declared May 20 “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day,” and, claiming the

project was sponsored by Citizens Against Citizens Against Humor, or CACAH

(pronounced, of course, ca-ca), posted a cartoon of her own by way of example. Interviewed on radio, Norris said she came up with the idea because “as a cartoonist, I just felt so much passion about what had happened”—“South Park” being censored—adding, “It’s a cartoonist’s job to be non-PC.” At her Facebook site, Norris later elaborated: “Why did I create this event? I thought the cartoon was a very nice (and polite and respectful) way of making the point that while Muhammad might well have insisted that he not be depicted by Muslims (to prevent idol worship), there are plenty of non-Muslims who value freedom of expression—and we can all live together with mutual respect. With many people all standing up for their right to depict Muhammad if they so chose, we would make an important point about how we were not going to cower before a handful of Muslim zealots.” Unfortunately, Norris promptly experienced a flood of unanticipated consequences— vicious, tasteless cartoons about Muhammad. Disgusted by what she saw, she withdrew from “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day” and disavowed the demonstration, saying: “Apparently this has turned into a mud-slinging fest because most people posting on this event's Wall just don't get it. I did not create this event to encourage people to be deliberately offensive, by equating the silliness of those zealots with the entire Islamic faith and its bazillions of adherents, a few of whom I am lucky to count among my friends. The histories and cultures of Islamic peoples are fascinating and inspiring, and the contributions of many Muslims to our world are innumerable. Hatred breeds hatred, and tolerance and respect breeds tolerance and respect. This event was not supposed to be about hatred but its opposite. I am aghast that so many people are posting deeply offensive pictures of the Prophet. Y'all go ahead if that's your bag, but count me out. Censorship is bad, mmkay, so I'm not going to delete all the posts on this Wall, but as the creator of this event on Facebook, I'll now mark myself as ‘not attending’ because, frankly, I don't want to be around most of you people. And I encourage you all to make some Muslim friends—those of you who clearly have never met a Muslim” And why did she launch the cartoon into the electronic ether in the first place? "Because I'm an idiot," Norris replied. "This particular cartoon of a 'poster' seems to have struck a gigantic nerve, something I was totally unprepared for," she said. She doesn't appear to be alone. The creator of a Facebook page dedicated to Everybody Draw Muhammad Day has bowed out as well. Jon Wellington told the Washington Post (before abandoning ship) that he created the page because he "loved [Norris's] creative approach to the whole thing—whimsical and nonjudgmental." While he was still associated with his own event he said: "To me, this is all about freedom of expression and tolerance of other viewpoints, so I hope you'll help make this a sandbox that anyone can play in, if they want. I don't think it'd be right under the circumstances for me (or anyone) to censor inflammatory posts *ahem*, but let's be welcoming and inclusive, mmkay?" Apparently the posts weren't "welcoming" enough: on Sunday morning he

announced his departure from the cause. Scott Beall posted his regret that “what was once a show of support for Free

Speech has become a movement that hates Muslims just because they are Muslims. I

have Muhammad as my default because I have the right to. ... I support that. But that

message is getting lost in this sea of intolerance that is no better than the intolerance

that extremist Muslims display. However everybody here has the right to say as they

wish but its just sad nobody will take this seriously now.” Asked if he had any rules about what or who he draws, Stantis said: “Under certain conditions, I can see drawing anyone or any body.” Did he think the reactions to depictions of Muhammad are overblown? “Any time you threaten violence, you lose the argument,” Stantis said, going on to comment about the current flap: “I can second guess Comedy Central's decision to edit the ‘South Park’ episode but I can see where they would not want to put themselves in harm's way. In terms of respect, I have to giggle at the notion of a faith that is so insecure that its icon cannot be held up to even depiction—it has a lot of internal work to do.” But doesn’t he draw the line somewhere? For example, would he draw a cartoon of Obama shot full of holes after an assassination attempt? Stantis, an avowed conservative, replied: “As I stated, ‘under certain circumstances’ nothing is off limits. While the example you offer is a cartoon I would never draw under any foreseeable circumstances, something could arise where that would be the right image.” With that, Stantis stood up and took off his bear costume, revealing that he was actually an editooning terrorist—namely, a voice crying reasonably in the otherwise loon-filled wilderness. ***** ANOTHER BOMB. According to telegraph.co.uk/news, police in New York thought, briefly, that the dud car bomb in Times Square on May 2 may have been aimed at the makers of “South Park” for their sullying of Islamic beliefs. The explosive-laden SUV was left near the offices of Viacom, owners of Comedy Central, the channel that airs the offending tv cartoon series. “Detectives are also understood to be investigating striking similarities between the New York bomb and two car bombs planted by Islamic hoodlums outside the Tiger Tiger nightclub in London in 2007. In both cases, the devices comprised cylinders of propane gas and cans full of petrol intended to be ignited by electronic detonators.” Wonderful. But before the sun set on this flash, the cops had apprehended the bomb-thrower, and so far (as of the end of the day, May 4), he hasn’t displayed any hostility to animated bear costumes or Santa Claus. * Footnit. As we’ve demonstrated here (Opus 254), Muhammad has been depicted numerous times, by both Muslim and non-Muslim artists. As for the origin of the prohibition: although the Koran does not specifically forbid pictures of the Prophet, many Muslims follow a tradition that regards such images as blasphemous. The Koran contains a general reference to the worshiping of idols being a “manifest error” without referring to pictures of Muhammad, but ancient oral traditions, called Hadith, quote Allah as saying it is “unjust” to “try to create the likeness of My creation” [i.e., anything in the world, I assume.—RCH] Islamic scholars are divided over whether it is ever permissible to depict the Prophet, but the controversies of recent years have been inspired by depictions that are mocking or disrespectful (as, ipso facto, all cartoons must perforce be). THE OTHER MUSLIM CARTOON CONTROVERSY While We Debated “South Park,” a Dutch Court Protected a Group’s Right to Publish Holocaust-denying Cartoons What follows herewith originally appeared, verbatim, on Judy Mandelbaum’s Open Salon blog on or about April 26. While she clearly disagrees with the Dutch court’s decision, she also presents the rhetorical posture of the Muslim perspective, which is not the hysterical Islamic hooligan posture. In the usual furor over Islamic hooliganism, we don’t often hear that other voice, which, it seems to me, has some validity. Anti-Semitic and Holocaust-denying cartoons are deeply offensive in our culture, but it is scarcely surprising that our attitude about them seems hypocritical to devout Muslims. Now, here’s Mandelbaum: All the media attention swirling around supposed death threats against the makers of "South Park" over a caricature of the prophet Muhammad overshadowed another story last week that might have a lot more to tell us about relations between the Muslim world and the West. Back in 2005, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten famously published a series of cartoons poking fun at Muhammad, which led to a global backlash resulting in the boycott and destruction of Danish products and over a hundred lost lives. A few months later a Pan-Arabist and anti-Zionist organization in Holland calling itself the Arab European League (AEL) published its own set of cartoons ridiculing the Holocaust on its website in order to illustrate "the double morals of the West during the Danish cartoon affair." The group wrote (in italics): The issue for us is not about depicting the Prophet or any other theological consideration. It's about stigmatizing a whole population of more than one billion Muslims through portraying their symbol as being a terrorist, megalomaniac, misogynic and a psychopath. This is racist, xenophobic and calling for hatred against Muslims. We do believe in freedom of speech but we think that respecting sensitivities and being constructive is also an added value to a democratic society. We are against laws oppressing any form of expression no matter how appalling it is. Nevertheless, we condemn the selective indignation of Europe's intellectual elite and population. When anti-Muslim stances are made or published this is perceived as freedom of speech and cheered and supported but when other sensitive issues to Europe like the Holocaust, anti-Semitism, homosexuality, sexism and more are touched, Europe's elite is scandalized ... ... Arabs and Muslims are facing occupation on the hand of the West, oppression on the hand of the dictators often supported by the West and aggressive colonization by the Zionist and apartheid state of Israel. Adding symbolic offense to factual aggression is responsible for the tension that we are witnessing today. Any attempt to understand the cartoons issue out of the current international context is completely missing the point. A Hague-based group calling itself the "Center for Information and Documentation Israel" then filed a formal complaint in Amsterdam, saying that the publication of the Holocaust cartoons was "a nightmare for the thousands of Jewish victims of the Holocaust who are still alive." The AEL in turn argued it was merely going after the West's own "sacred cows," referring to a disclaimer it had posted stating that "in our cartoon campaign we do not endorse any anti-Semitic, homophobic or sexist stands. All we are trying to do is to confront Europe with its own hypocrisy using sarcasm and cartoons." Last Thursday a Dutch court ruled in the AEL's favor, stating: "The context in which this cartoon was published takes away from its criminally offensive nature." So that appears to be that. So, let's take a look at these infamous AEL caricatures:

So [Mandelbaum continues], are you shocked and appalled and already heading out the door for the nearest courtroom? Or, like me, are you merely surprised at how weak and downright incomprehensible these cartoons are? I mean, I've seen far better on the pages of (junior) high school newspapers! It beats me why anyone would bother taking these guys to court—couldn't the money be better spent on giving them a couple of drawing lessons? And yet—that's also how I felt about the original Muhammad caricatures. While I will always support a free press as far as I have to go to protect it, the Danish campaign—which was intended as a deliberate provocation—always seemed petty and mean-spirited to me, and the global reaction was a foregone conclusion. There was certainly nothing about those spectacularly unfunny drawings that could ever deserve the name "comics," and the same goes for the AEL's trashy Holocaust caricatures. You see, genuine comics charm and delight us. They make us laugh as they teach us about human nature. Thoughtful strips like Doonesbury and Peanuts, and clever political cartoons by such skillful artists as Pat Oliphant and Tom Toles—as hard-hitting as they sometimes are—enrich our lives while exercising our smile muscles. And then there's the kind of toilet graffiti that tears down and demeans—and no one so much as the "artist" who sprays his or her message out into the world like an unpleasant body odor. And that's the kind of "comics" I'm talking about here. They just aren't funny. Okay, I'm going into utopian mode now. Be sure to close the skylight before I head off through the roof! But it seems to me that if we could somehow harness the power of comics to laugh at our own foibles and take the occasional jab at our respective holy cows—just as Daniel Barenboim is using the power of classical music to bring Israeli and Palestinian young people together in his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra— we would all be a lot farther ahead than we are at the moment. A while back, an old comedian explained to me the difference between German humor and Jewish humor. In German humor, he said, you always need a victim. Whether it's Jews or Poles or brunettes, somebody has to bleed. In Jewish humor, by contrast, you always make fun of yourself. Guess which kind is funnier.

**** WHILE I AGREE THAT THE QUALITY of the artwork in these cartoons is not very high, it is difficult on any level save the purely rhetorical to equate the Holocaust with drawing pictures of Muhammad, as the AEL argument does. But we in the West are notoriously insensitive to the cultural nuances in Islamic societies. Partly that’s a consequence of simple small-minded, self-absorbed insular myopia, for which citizens of the U.S. are celebrated worldwide; partly, our ignorance and insensitivity is due to the failure of our various information services to inform us. The circumstance is particularly and odiously obvious with respect to the dilemma confronting Israelis and Palestinians. At the very end of this posting, I’ve laminated on my previous essay on this subject, under the ludicrous but apt heading “Mess-o-patomia,” Jon Stewart’s coinage, I believe. ***** From Agence France-Presse: Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard, who has been

attacked and repeatedly threatened over a drawing of Prophet Muhammad, has been

placed on indefinite leave by his newspaper "for security reasons," he told AFP. "It is

forced vacation but it looks a lot like I'm being retired," the 75-year-old cartoonist said,

adding that he himself still had an "insatiable desire" to work. The newspaper, Jyllands-Posten (for which he drew Muhammad in a bomb-like turban in 2005), often allows

people over the official retirement age of 67 to continue working, he said, but the paper,

in his MORE AWARDS FOR EDITOONERS Mike Peters (Dayton Daily News, Ohio) won the 2010 Headliner Award for editorial cartooning; Dana J. Summers (Orlando Sentinel, Florida) was runner-up followed by Steve Breen (San Diego Union-Tribune). The Washington Examiner’s Nate Beeler, who does one of the best Obama caricatures in captivity, won the Thomas Nast Award from the Overseas Press Club for his work throughout 2009. The press release states: “Nate Beeler’s entries stood out for their powerful and vivid composition that brings the message home regardless of whether the cartoon centers on a conversation or a visual punch line. Notable for his use of color and for meticulous art work that, in the words of one of his editors, ‘treats each cartoon like a painting.’” And Bill Day, syndicated by United Feature but without a home newspaper, won

the editorial cartoon award in the 42nd Annual Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards.

The press release cited him for “shedding light on the continuing problem of infant

mortality in America, especially among minority populations. His unusual special project

creates clear and easily- readable cartoons, raising public awareness, partly through a

grassroots movement that led to legislation and policy improvements.” **** Alan Gardner reported at his DailyCartoonist on April 22 that Technicolor will move into television animated programming by bringing Berkeley Breathed’s children’s tale, Pete & Pickles, to the small screen. Breathed was, as usual, able to deliver a comically cynical and extravagantly promotional remark about the development: “I told the folks at Technicolor,” he announced, “that the only way I could get lured to the world of small screen pixels is if a company were to declare their intent to make the coolest, most unique animated show for children’s television — one that shakes up the art-form like my son shakes the grocery bag full of eggs just because its fun. The sneaky schemers agreed.” FRAZETTA FLAP FOLDS Fantasy artist Frank Frazetta's children have ended their dispute over his estate and artwork , according to a statement from the family issued April 23. The feud came to light in December when Frazetta's oldest son, Frank Jr., was caught with a backhoe breaking into his father's Pennsylvania home, saying he was trying to take his father's $20 million collection of art to safeguard it from his siblings. They claimed he was going to sell the art and keep the money himself. He, on the other hand, claimed his brother and sisters had plotted to cut him out of his father's estate, take over the Frazetta business, close the museum, sell of the art, and leave him with nothing. Frank Frazetta, 82, stayed out of the dispute, mostly; he has suffered from a series of small strokes that impair his ability to draw. He maintains a small museum of his work on a farm in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. His four children have been squabbling over his estate since the death in 2009 of their mother, who handled all of her husband’s business affairs. Now that they’ve settled, Frank Jr.’s brother and two sisters have asked that theft charges against their brother be dropped. "Frank Frazetta is pleased to announce that all of the litigation surrounding his family and his art has been resolved. All of Frank's children will now be working together as a team to promote his remarkable collection of images that has inspired people for decades," the statement said. A final decision on the theft charges will be up to county prosecutors. ***** In His Own Words: Frazetta About the same time the foregoing report arrived at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Outpost so did an issue of Russ Cochran’s e-newsletter in which he publishes parts of an interview he conducted with Frazetta in September 1998. Here are excepts, with my transitional devices in italics. “I had a thousand influences,” Frazetta said, “—Dick Tracy, Smilin’ Jack, and all the rest—inferior art, comparatively speaking, but it helped make my imagination very fertile. Like every kid who grew up in that period, I was influenced by movies, radio serials, comics, and we often got sidetracked. I got sidetracked at the age of eight when I started art school [Brooklyn Academy of Fine Arts], and then re-discovered Harold Foster [in the Tarzan comic strip] as a teenager when the Single Series No. 20 appeared. That comic book was, to me, the Encyclopedia Britannica…fantastic! Before that, I was sidetracked by what Walt Disney was doing in his animated cartoons, and by Popeye—I just loved Popeye to death. I could draw Popeye like crazy. And I was a big Caniff fan in the thirties, but when I discovered the Tarzan Single Series No. 20 by Foster, it put me back on the path to good art. Not to knock Caniff at all, but compared to Foster, we’re talking about comics versus fine art. Foster reminded me just how good art could be! I was thinking about being a fine artist, or maybe a cartoonist.” Thus, inspired by Foster, Frazetta very early on began to dream of drawing

Tarzan. Cochran reminded him that Foster reportedly worked at least sixty hours a

week on his later strip, Prince Valiant—without assistants. Frazetta got his own comic strip, Johnny Comet, in 1952, but he wasn’t happy drawing about automobile racing. He still dreamed of doing Tarzan. “In those years I always had Tarzan in the back of my mind,” he said. “Tarzan was my favorite character, forever and a day. And there were guys out there like Vern Coriell, trying to wrangle for me. That’s what got me discouraged. I knew that Vern was showing them my stuff and saying, ‘You’ve got to get this guy Frazetta to do Tarzan!’ And he couldn’t get anywhere with them. Who could show more enthusiasm than him? No one seemed to give a damn until it was too late—until I found other channels and started making a different way for myself, and got totally disenchanted with the idea of doing a strip. Not with Tarzan, but with the idea of grinding out a strip. After it was too late, Burroughs called me to do Tarzan, the syndicate called me to do Tarzan—everybody wanted me to do Tarzan. But by then I knew from Johnny Comet and from working for nine years with Al Capp on Li’l Abner that there was a lot of work involved, and it’s not fun. Whether you love it or not, it was just plain hard work. And I had discovered that it was much more satisfying to do one picture. Doing a continuity was no longer satisfying. I thought that you couldn’t put out a hundred percent and stay sane. But doing paintings, one picture at a time, I could put out a hundred percent.” HEFNER SAVES HOLLYWOOD The famed “Hollywood” sign atop Cahuenga Peak overlooking Los Angeles was on the cusp of being cluttered up with a luxury home development, Tinseltown freaked, and concerned citizens launched a campaign to buy the property from the developer in order to guarantee that the iconic sign would survive unencumbered by residential real estate. The purchase price was $12.5 million, but the project was a million short of its goal as the April 30 deadline loomed. Then Playboy’s Hugh Hefner jumped in and saved the day, and the sign, with a $900,000 donation. "Turned out the kid was back in the water again," Hef quipped. In 1978, he played a major role in a campaign to fix up the then-terribly dilapidated Hollywood sign. Ensuring that the land would remain undeveloped was worth taking action again, he told the Los Angeles Times. "It's like saying let's build a house in the middle of Yellowstone Park. There are some things that are more important. The Hollywood sign represents the dreams of millions. It's a symbol. It is as the Eiffel Tower is to Paris. It represents the movies. My childhood dreams and fantasies came from the movies,” he added at GossipCop.com. “The images created in Hollywood had a major influence on my life.” Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, no stranger to filmdom, referred to the last-minute sign salvation as “the Hollywood ending we hoped for.” The mountaintop acreage once belonged to movie mogul Howard Hughes, who

planned to build a love nest there in the 1930s for a girlfriend, actress Ginger Rogers.

(She wouldn't let him.) The land languished unbuilt upon and forgotten until 2002, when

a group of Chicago investors bought the land from the Hughes estate at a bargain-basement price. When they announced plans to subdivide the peak into five luxury

home sites and try to sell them off for $40 million, city officials were as shocked as residents. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment and some of what follows is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. QUOTES AND MOTS “Skating on thin ice is better than skating on no ice at all.”—John M. Shanahan “My life is in the hands of any fool who makes me lose my temper.”—Joseph Hunter “Without the aid of prejudice and custom, I should not be able to find my way across the room.”—William Hazlitt “The freedom of the press works in such a way that there is not much freedom from it.”—Grace Kelly, commenting, no doubt, on the hordes of photographers who haunted her in the days of her fame as the intended bride of Prince Ranier of Monaco ARCHIE RESURGENT I suppose we should have seen it coming. With all the ravening excitement attending last summer/fall’s 6-issue series rehearsing Archie’s bigamy with Veronica and Betty, we should have realized at once that the watershed concept wouldn’t end with the epilogue issue, No. 607: the whole notion of Archie in the throes of wedlock is simply too rich with story possibilities to ignore. And, sure enough, now comes the announcement that Michael Uslan, who committed the notorious bigamy saga, will continue to exploit the idea of Archie being married simultaneously (so to speak) to Veronica and Betty in a prolongation of the theme to be perpetrated in The Married Life: Archie Loves Veronica and The Married Life: Archie Loves Betty. Promotional material shows two comic book covers with those titles, but when Brigid Alverson at Publisher’s Weekly talked to Archie CEO Jon Goldwater and managing editor Mike Pellerito, another format seemed on the table—namely, Life with Archie, a comic “in magazine format that would carry two parallel stories”: in one, Archie is married to Veronica, and in the other, he is married to Betty. "It will show their lives as young married couples and all the issues they encounter," Goldwater said. "It's not heavy handed, but there's going to be a little bit more meat on the bone." The magazine comic book stories will be drawn by Norm Breyfogle in Archie Comics’ “New Look” manner, a somewhat more realistic (or, perhaps, manganese) manner. “I didn’t have to change my style as much as one might think—or as much as I originally thought I’d have to,” Breyfogle said. He changed his way of rendering mostly with the faces, for which he perpetuated the traditional Dan DeCarlo style. Said he: “I’ve found that as long as the faces and body proportions are in the traditional style, everything else can be more or less pretty ‘realistic’ or dramatic, although perhaps a bit simplified.” Uslan warned of forthcoming changes when he was interviewed by Optimous Douche at aintitcool.com: “You'll be meeting a whole new cast of characters in New York with Archie and Betty, and will be learning how Archie's choices have dramatically impacted and changed the lives of all their friends and families in Riverdale. Riverdale will become an important character itself in these new series that take place just after the weddings and before the issue of children becomes a reality. Do not think the Lodge fortune brings Archie comforts and has bought him happiness either! Do not think that with Betty love conquers all their very big struggles in the City trying to make ends meet. And wait till you see what, in each of the two scenarios, happens to Jughead, Moose, Dilton, Reggie, Mr. Weatherbee, Pop Tate, Miss Grundy, Mr. Lodge, Chuck and Nancy, Midge, Ethel, and the rest!” By way of example, Uslan continued: “Mr. Lodge promotes Veronica over Archie, making her his boss! Cheryl Blossom gets a job in Hollywood that is shocking to anyone who knows her! Chuck Clayton gets his first pro job in comics drawing a newly revived Steel Sterling for MLJ Comics Group! And we have three big shocks for Moose fans! And keep a sharp eye out for the alum who has seemed to disappear off the face of the earth, Dilton Doily! What Doc Brown was to ‘Back To The Future,’ Dilton may well be to the Archie Universe!” Uslan sees no particular problem in violating the Archie universe by running a married Archie series at the same time as the regular Archie books focus on the redhead’s high school exploits: “Batman, for example, has already proven that there can be several different versions co-existing at the same time without confusing the marketplace. Thus, kids can watch ‘Batman: Brave & Bold’ or ‘Batman Meets Scooby-Doo’ while an older audience can savor the other animated versions and comic book versions, all leading to our live action ‘Dark Knight’ movie version.” AND THAT’S NOT ALL. As if bigamy doesn’t shatter molds enough, in Veronica No. 202, out in the fall, the Archie operatives will introduce a gay character, a slender but hunky Kevin Keller, in a story entitled “Meet the Hot New Guy.” Written and drawn by Dan Parent, the idea for the story—and the character—“came as a new twist on the perennial story of Veronica's selfishness,” reported PW’s Alverson. Goldwater explained: “Dan’s concept was, ‘What if Veronica can't get something she wants,' and we said, ‘What couldn't she get?' and he said ‘What if someone is really good looking and she wants to date him and she can't because he's gay?’ It really just came out of a creative meeting more than ‘Let's plan this whole thing.'" Parent has a teenager of his own, said Nina Kester, Archie’s director of new media: "He has been talking a lot about the genesis [of the story], that his daughter interacts with gay friends at school and it's completely the norm there, so this is the perfect opportunity to include it in Riverdale.” And it is likely that Kevin is here to stay, said Pellerito:"I think Dan already has three or four stories in the works.” Douglas Wolk, previewing the story at salon.com, said: “It appears Parent is

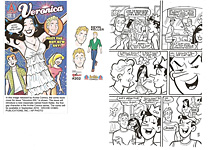

treating Kevin's orientation as a surprise but not a shock: the hot new guy is being

pursued by Veronica but has no interest in her, Jughead advises him that she's pretty

persistent, and Kevin declares: ‘It's nothing against her! I'm gay!’ To which Jughead's

immediate reaction is deciding to wait and let Veronica figure it out for herself, and the

plot goes on.” Kevin feels kind of bad and thinks he should tell Veronica, but Jughead, whose sense of humor is more than a little perverse, insists Kevin should wait because he, Jug, enjoys watching Veronica make a fool of herself. Parent, quoted at newsarama.com, said the story works because it isn’t something radical concocted just to introduce a gay character. “The story is very much in the true context of our Archie stories,” he said. “It’s Veronica being Veronica. The fact that there’s a gay character in the story isn’t a big deal to the characters. We didn’t do something with turmoil. The guy just happens to be gay, and the characters accept it, and that’s it,” Parent finished, adding that Archie Comics wants to reflect what high schools are like in America where being gay “isn’t a big deal anymore.” Well, yes—except for the Archie tradition. Wolk points out that Kevin is scarcely the first gay character in comics: superhero comics have introduced several of this sexual persuasion. But, he continues, “the significant distinction here is that, unlike superhero comics, Archie comics are specifically aimed at kids (well, and at aging collectors who remember reading them as kids, but the kids are the primary audience): they're a fantasy about what high school is like. That's why the addition of Kevin to the series' endless comedy of desire and disdain is welcome and long overdue. The social fabric of high school is going to include gay people, and the sooner kids (and aging collectors) take that as much for granted as they do the Archie/Betty/Veronica love triangle, the better.” Wolk goes on: “Outside the ‘safe world for everyone’ that Archie Comics' Jon Goldwater says Riverdale represents, this is, of course, a hot-button issue, and if Archie Comics actually wanted to suggest that it's no big deal, they'd have just published the story instead of announcing it via press release long before it appears. (Honestly, somebody protesting a fictional character's entirely chaste homosexuality would be the best possible publicity for this project.) It's safe to assume that the primary audience for this particular issue of Veronica will be people who haven't bought an Archie comic in decades, unless they also bought those similarly hyped-up comics a few months ago in which a future Archie married Betty or Veronica.” But Kevin clearly represents a massive sea-change at Archie Comics, Wolk says. “The comics-historical significance of Kevin's appearance is that it marks a shift in the Archie franchise's history. The Riverdale gang appeared in a series of very conservative Christian comic books in the '70s and '80s. And in 2003, playwright Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa—who's also written for Marvel Comics and ‘Big Love’—wrote a play called ‘Archie's Weird Fantasy,’ which involved older, gay versions of the Archie characters, and was blocked by a cease-and-desist order shortly before its premiere. (It was promptly rewritten as ,Weird Comic Book Fantasy.’) So how big a deal will Kevin end up being in the long run? Probably not much of one. ... Even if Kevin sticks around, it's hard to imagine him having a role beyond ‘the token gay guy.’ That's just hard-wired into the premise of the last 68 years' worth of Archie comics: There's a small, limited group of characters, and everyone gets exactly one personality trait. And it's safe to assume that the first same-sex kiss in an Archie comic is a good long ways off —the interracial kiss on the cover of this week's Archie No. 608 was a long time coming, too.” But the best possible publicity for Kevin Keller’s arrival began surging in the electronic ether almost as soon as the news seeped out at the C2E2 (Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo). At CNN’s website message board, comments initially blurted with the typical bigotry—a parent vowing to ban Archie comics from his home, another moaning, “This is crazy. Why do they have to bring gay people into everything?”—but more enlightened attitudes eventually prevailed. And syndicated columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr.—among the most enlightened of American journalists—weighed in with his customary insights: “This looms as a watershed moment. That's precisely because Riverdale exists at that junction of wholesomeness and Americana. There are few entities in mass media more conservative than Archie Comics. ... So when it comes to introducing Riverdale's first openly gay teenager, the salient issue isn't how well they do it or what they stand to gain from doing it, but that they are doing it at all. “Can you imagine the company feeling compelled to introduce this character 20 years ago?” Pitts continued. “Or even 10? Of course not. Twenty years ago, homosexuality was dangerous, 10 years ago, it was risqué. The appearance of a gay character in Archie comics strongly suggests that it has become, is becoming, mainstream. Even safe. People like those on CNN's message board must surely know they're fighting the rear-guard action of a battle they've already lost. When a Kevin Keller enrolls in Riverdale High, that's a white flag running up the pole, enemy soldiers raising their hands. “Which is not to suggest the fight for full gay citizenship is won. But it is to suggest that the parameters of that fight have changed. It is to suggest that, message board malcontents notwithstanding, we are at least done contesting the very right of gay men and lesbians to simply be—and to be seen, being. “Occasionally, and understandably, one hears gay people complain about the slow pace of their progress. But progress has this way of sneaking up on you, of suddenly being there when you didn't see it coming. We think progress is a lightning bolt and sometimes, it is. But more often, it is a series of incremental changes whose full importance we see only in hindsight. This will likely be one of them. So what should we say now that there is a homosexual in Riverdale? How about: Welcome to the 21st century. We've been waiting for you.” At comicbookresources.com, Dan Parent elaborated on the task facing Archie Comics: “The key is to bring this character into the future of the Archie characters and the town of Riverdale. We want to make sure Kevin can continue on and won't be just a one-shot, which he's not going to be," Parent said, adding that he and his editors took care to make sure the story was handled in a respectful and common-sense way. "We did have to revise the story a few times. It wasn't like writing a regular Archie story because we were aware of what we were doing. That I'll tell you: we were aware of what we were doing. We were aware we were doing something that could be controversial even though it shouldn't be controversial.” He continued: “The bottom line is this: the story has to be a good story, and the character has to be well-written. We've still got a lot more to explore with the character. He's just introduced here, and the angle is more on Veronica. She's the one who has the hots for the character. So we learn a few things about him, but he's just like your typical teenager moving into a new town and trying to fit in. That's really the gist of the character. They discover he's gay, and they accept it. And I'm not saying that's the way it always happens everywhere across the country, but in Riverdale, the Archie characters accept him as another friend. That's where we're going with this. Riverdale is a tolerant town and everybody is welcome in Riverdale. With this whole diversity movement we're working on, we couldn't not have a gay character. Everybody has to be invited along. If you look at a high school now, there are a lot of gay teens who are open. That's the reality now, and it didn't seem right to ignore that.” Parent told CBR that from the start, introducing Kevin Keller into Archie's world was part of a broader strategy at Archie Comics to make Riverdale more diverse while avoiding the pitfalls of stereotypes and parody. “And we have Jon Goldwater, our new CEO,” Parent said, “and he's behind this idea to keep things moving forward. We've got new blood in the company. We've always tried to be diverse and in the past several years we've gotten really aggressive with that and have brought in a lot of different ethnicities, and we'll continue to do that this year. It's just about being relevant and modern. We're trying to keep up with what's up in pop culture and society. From introducing Kevin to doing parodies of modern TV shows, it's all about staying fresh to our readers.” Of late, the focus for everyone at Archie Comics has been finding new ways to tell more in-depth and relatable stories with the characters across the line. Said Parent: "We're definitely looking forward to doing graphic novels, and the multi-part stories have worked well for us. The longer stories are working well for us because even though the five-pagers are good and funny, you can do so much more with a longer story. You'll definitely be seeing a lot more of those." Parent knows he has to focus on telling stories with all the characters one comic

book issue at a time. "I can only focus on writing good stories and doing the best I can

do," he said. "I know a lot of discussion will come out of this, and it will probably make

the national news. What will happen is that it will get a lot of attention up front, and then

a few months later it'll die down. Then, the character of Kevin will become a regular part

of Riverdale, and people will get used to it." A NEW HAND ON THE TILLER. A sea change at Archie is definitely underway—and has been, most obviously, since Jon Goldwater, son of one of the company’s founders, became co-CEO of the company last summer. It began earlier, soon after the August 2008 death of Michael Silberkleit, who was Archie’s chairman and the last of the first generation of successors to the founders. Silberkleit with Richard Goldwater, Jon’s older brother, “steadfastly refused to introduce the worldlier and darker elements of teenage life, like sex and drugs and violence, into the Archie storylines,” saith newsarama.com. “In doing so they preserved an image of adolescence for the target audience of 7-to-14 year olds. Silberkleit was determined to keep Archie an American institution, pure as childhood, yet up-to-date with the latest technology used by children today. For generations of readers, Archie and the Gang have represented the wonder and magic of childhood and Silberkleit fought successfully to keep this vision alive.” Silberkleit was solely in charge of the company after Richard’s death in October 2007, and he refused to make any substantial change in Archie’s time-tested successful formula of short story comedy about mostly pleasant adolescents. In one of the many interviews Silberkleit gave, newsarama quoted him as saying: "The fact that our stories are funny, are non-violent, believable, clean and appropriate for youngsters makes us so appealing to the younger reader. This philosophy hasn’t changed for more than 60 years. Many parents grew up reading Archie Comics and feel that our comics are appropriate for their kids." The bigamy series was developed before Jon Goldwater officially took over—again, almost by accident during a conversation between Uslan, who would write the series, and editor-in-chief Victor Gorelick, who, at the age of 60, had been working in the company in various capacities since he was 16 years old. But he is apparently a bit more adventurous than Silberkleit. Interviewed last summer by Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, Gorelick remembered the origin of the marriage idea. He and Uslan were talking, and Uslan, being a big Archie fan, said he wanted to write something for Archie. Gorelick said: “I have this 600th issue coming up— let's do something. He came in with this idea of Archie getting married. I said: ‘What, are you crazy? I have to really think about it.’ Five minutes [later], I thought it was a really good idea, so I said: Let's go for it.” It was Archie in an alternative universe, so the marriage was not, just then, envisioned as a permanent change in the Riverdale milieu. Still, Gorelick very much wanted to do something exciting, he said. “We knew it might be controversial. But we can't do what comics like Superman or Batman do and kill off Archie. Seven [decades] of people have been reading this. There are certain things we stay away from. We produce a good, clean wholesome product—there's not a lot of antisocial behavior. That's helped to make [and keep] Archie popular. There are no metal detectors and police walking around at Riverdale High.” But he knew the Uslan idea would be huge: he ordered four times the usual print run for the comic books. Then, as the first of the series was being printed, Jon Goldwater arrived, galloping through the staid hallways of Archie Comics like a wild stallion. He looks over the media landscape and sees a vast horizon of undeveloped potential, and he aims to develop it and establish Archie Comics as an entertainment empire. Just listen to him (from a February 2010 interview with DBR News about Archie’s team-up with Stan Lee to produce a new superhero title, Super Seven, wherein writer Lee will be a member of the cast): “There's certainly web stuff lined up that we're going to do. We're going to get the comics out, because the distribution network with Archie is really big with both the newsstands and the supermarkets. We're going to gear towards getting the book out in our traditional venues and the direct market, and digitally as well. This will be up on iTunes and ready for digital downloads. And we want to do webisodes and the whole thing. It's going to be very, very vibrant and rich in terms of the publishing side of things. Andy Heyward with A-Squared is going to be in charge of all the animation and live action movies and all the other things that come with creating wonderful new superhero characters. And we're going to be trying with that as fast as we can, but most importantly we want to create a great comic book. Because from a great comic book, everything else springs. That's our first goal. Once we say, ‘All right...we have just hit a grand slam in the bottom of the ninth inning with this comic,’ then we'll attack everything else. That's the foundation of everything we're building right now—to create a great comic book.” But a great comic book is just the beginning. Goldwater continued: “I would have to say the Josie thing [a pending tv show with Josie and the Pussycats for Teen Nick] is something you can watch out for. That's coming down the pike without a doubt. As far as the other stuff—Archie stuff and Sabrina stuff—we're hoping in 2011 you'll certainly see animation for both. Our feature films for all our characters are probably a couple of years away in terms of actually seeing them on screen, but know that they're currently in development and that we're working on them every day. It's sort of like moving a mountain, because Archie hadn't moved in so long. It's a process. And most importantly, my initial focus coming in was to fix the publishing division. I wanted to make the publishing division as strong, as vibrant and firing on all cylinders as it could be. “And when I say ‘fix it,’ I don't mean that it was broken. I mean that we needed to reinvigorate it. We had the engine, but it needed some high quality gas. That's how I look at it. We gave it some high quality gas, it's starting to hum a little bit, and once the publishing division is where we need to be, then everything else will come from that. And I think the future in other media is phenomenal.” At Publisher’s Weekly, Alverson, observing that Archie Comics will celebrate it’s 70th anniversary next year, reviewed the company’s plans for the immediate future: a forthcoming series of story arcs in Archie and Friends will venture into parody, a place Archie has never gone before. And a multi-title crossover will start with No. 145 and “really shake up Riverdale. Written by Alex Simmons, the story will examine what happens when a nearby school closes and Riverdale is hit with an influx of new students. Suddenly Veronica may no longer be the richest girl in school, Moose may no longer be the strongest guy, and all the characters will have their worlds upended. The story will run across every comic in the Archie line, and the covers of all the comics combine to make one large scene. Later this year, the publisher will launch a series of direct-to-digital comics that will be published on the iPhone/iPod Touch and iPad and then collected into printed graphic novels, featuring Dilton Doiley, Josie and the Pussycats, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, and Li'l Jinx, who will now be known simply as Jinx.” "Our digital sales are continually increasing every month," Goldwater told Alverson. "Archie: Freshman Year is the most downloaded comic in iTunes history. The Archie app has been downloaded hundreds of thousands of times on iTunes and iPad." In addition, Archie comics will be included in comiXology's new Comics 4 Kids app.” Goldwater spent years in the movie and music industry and applies his experience. "We embrace new technology," he said. "It's one of the lessons I learned from the music business, when the whole music business fought what was happening with Napster and instead of embracing it rebelled against it. Look at what has happened: it shrunk. The lesson to be learned is embrace new technologies, make them your partner, bring them along. It only adds to the visibility of your content." Uslan is delighted. “Corporately, a sleeping giant has awakened,” he told Optimous Douche. “Archie Comics Group had traditionally been considered a mom and pop comic book company. Today, it is daring, adventurous, and pushing the envelope in every aspect of comic book publishing, mass media and delivery system platforms. That's great for the company, great for the characters, and great for the fans and the readers among the general public. Creatively, they are wide open and encouraging of exploring new concepts and breaking old rules and generally ‘going where no man has gone before.’ As a creator or writer, I love this environment! As a comic book historian, I feel that as long as the essence of the characters are retained and their integrity is not violated, the exploration of alternate universes and time periods and big events will work as well for Archie as they have for DC and Marvel.” The awakened giant stalks the land. ***** A headline in a recent issue of Parade magazine announced the findings of yet another survey: “Developed World Leads on Gay Rights.” Same-sex marriage is legal in Canada, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, South Africa among a few others. Homosexual acts are punishable by death in Iran, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Mauritania, and parts of Nigeria and Sudan. Sanctions against homosexuals seem to be easing in China, Singapore, Cuba, and Nepal; they’re tightening up in Burundi, Nigeria, Russia, and Uganda. THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution Philadelphia’s two daily newspapers, the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News, both bankrupt, went up for auction on April 28, and creditors won “the frenzied bidding” with a $139 million bid, despite last-minute pledges from local philanthropists to boost a local group's bid. The new owners include the hedge funds Alden Capital and Angelo Gordon & Co., along with Credit Suisse and other banks. They will install a former publisher of the newspapers, Robert Hall, as interim chief executive officer. Hall pledged not to merge newsroom operations at the broadsheet Inquirer and smaller, tabloid Daily News, saying he will instead market the unique "flavor" of each, according to the Associated Press. The creditors also agreed during the bidding to negotiate with the company's labor unions rather than oust them — and gut the staff — as many had feared based on speculation about the creditor's initial bid. Together, the newspapers have 2,000 full-time and 2,500 part-time employees, most of whom are unionized workers. Signe Wilkinson, Daily News editorial cartoonist, said there was much uncertainty in the newsroom after the auction, but that everyone was hoping for the best. "Nobody knows what it means yet," said Wilkinson, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. "People are still uncertain.I hope the owners respect the fact that these are two terrific newspapers," she said. Each of the two papers has its own editorial cartoonist: Tony Auth is at the Inquirer.

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted In response to the Mark Fiore Apple app flap we reported last time, the Association of

American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) has issued a call to Steve Jobs and Apple Dear Mr. Jobs: The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists would like to commend Apple for approving Mark Fiore's app, "NewsToons" (which incidentally became the top selling news app in less than 48 hours). Ironically, Apple rejected this very app as "objectionable" until Mr. Fiore received the 2010 Pulitzer Prize and considerable media attention. We hope other apps that focus on politics and satire do not have to wait for a Pulitzer Prize before they are approved by Apple. The recent attention given to Apple's rejection of apps because they "ridicule public figures" and are therefore in violation of the iPhone developer agreement, has brought some very important free speech issues to light. Apple's policy forbidding ridicule of public figures effectively bans all political cartoons and satire from the iPhone and iPad. While the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists realizes that Apple is a private sector company, Apple is also becoming one of the primary ways people publish news and information. With that innovation comes new responsibility. A vigorous public discourse, opinion, satire and, yes, ridiculing public figures, are essential to journalism and our democracy. Our nation would be a very different place if early technological innovators like Benjamin Franklin and those who followed him, forbade their presses from being used to ridicule public figures. Instead of approving apps containing news and satire based on popularity, the quantity of public outcry, or the quality of award the work has received, there is a much simpler solution. The AAEC calls on Apple to immediately stop rejecting apps because they "ridicule public figures" and are deemed "objectionable." Now is the time for Apple to welcome a vibrant and diverse world of news and opinion with open arms. We would be happy to meet with you to discuss this matter further and look forward to journalism and press freedom being an important part of Apple's continued innovation. LUCKOVICH’S LUCK

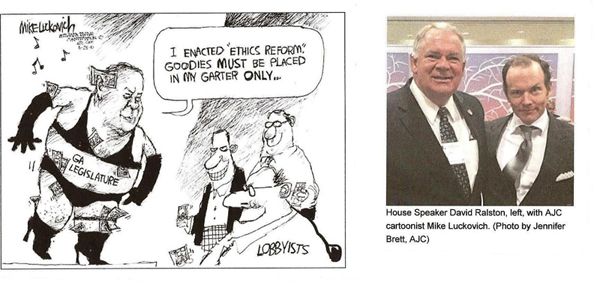

Mike Luckovich’s cartoon featuring a scabrous caricature of Georgia House Speaker David Ralston appeared in his paper, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, on Wednesday morning, April 28. That evening, Luckovich went to a dinner to be honored by the Georgia First Amendment Foundation; Ralston was the guest speaker at the event. AJ-C blogger Jay Bookman reported that Ralston had been more than a little bemused on Wednesday morning when he opened his paper. “‘What a coincidence,’ he thought, that his first starring role in a Luckovich cartoon would occur that very day. But to his credit he never thought about withdrawing from the evening’s event.” Then the phone started ringing as friends called to tease him about the cartoon and to laugh with him. Bookman recorded Ralston’s jocular quip: “My mother called today and said, ‘If you’ve gained that much weight, it’s time to come home.’” That evening, the dinner’s sponsors, Bookman said, were “worried that the event might be marred by hard feelings between the guest speaker and the honoree,” but apparently they were no more in on the joke than Bookman. “The cartoon turned out to be one of the highlights of the evening,” Bookman continued. “When Luckovich showed up to receive the foundation’s highest award, the 2010 Charles L. Weltner Freedom of Information Award, he brought with him the original of the cartoon and presented it as a gift to Ralston. In the margins of the cartoon, he noted that he had once drawn Ralston’s celebrated predecessor, the late Speaker Tom Murphy, wearing nothing but a diaper. In other words, nothing personal. A grinning Ralston gladly accepted the cartoon, ostensibly as a peace offering.” Then he sprung a surprise of his own. “Your honoree and I had a private discussion earlier,” Ralston told the audience. Summoning Luckovich to the podium, Ralston continued: “Since I believe in reciprocating, I brought you a little something.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a black garter, handing it to a gleeful Luckovich. Calling Ralston “a really good guy,” Luckovich promised that he would never draw the speaker again. “Well, at least not naked,” Bookman finished. “The Speaker was no doubt grateful, and so are the rest of us.” I have an irrepressible suspicion that the entire episode was one of Luckovich’s

legendary practical jokes. Winner of both the Pulitzer and the NCS Reuben, Luckovich

is notorious for committing satirical drolleries in public. He has attended more than one

occasion of high ceremonial import wearing dark glasses with one end of a phone cord

stuck in his ear, the other snaked down the back of his neck and under his jacket collar.

This crass impersonation of a security personage seems to work. At the White House

Correspondents’ Association Dinner in 2006, Luckovich perpetrated this prank and

managed to fool Henry Kissinger, who asked Luckovich to escort him to the security