|

||||||||||||||||

Opus 257 (February 28, 2010). Before we get around to celebrating Black History Month, I plunge headlong into the national disgrace being perpetrated on us all by the way Christopher Handley and his collection of manga are being treated by our so-called justice system. Reading about his case, I have difficulty believing we’re still living in the land of the free and the home of the brave. There ain’t much justice in Handley’s case: the judge displayed admirable forbearance in sentencing the manga collector, but the law under which he had to operate is a blatant offense to the ideas upon which this country was founded. Justice done under that law is justice perverted. After inveighing against that disgrace, I meander through various news items of the last few weeks and wind up with an abridged history of black cartoonists in the mainstream press. I started out thinking I’d contribute to Black History Month with short bios and appreciation for the work of three of my favorite African American cartoonists—Ted Shearer, Ray Billingsley, and Milton Knight (who I lost track of for a decade or more but who I have found again). But in setting it up with what I intended as a short introduction, I was seduced: the more I got into it, the more I got into it. I came across a comic strip called Tempus Todd, ostensibly the first mainstream comic strip with an adult black male as protagonist—and after that, I followed wherever the crumbs in the forest led me. And before I got to the three I started out heading for, I paused over Morrie Turner, so fateful a distinguished pioneer that no attempt at an overview of the African American in comics can pass him by. Ditto Ollie Harrington, Jackie Ormes, and Bungleton Green. Having piled all these people up, I then realized I’d neglected comic books, and before I knew it, I was into Milestone, and on and on. There’s more, though, between here and there: here’s what’s here, in order, by department: OUR NONEXISTENT LIBERTIES The Shameful End of the Christopher Handley Case NOUS R US Marvel Apologizes to the Tea Baggers Who Would Win? Batman or Superman? Steve Geppi’s Financial Woes Eduardo Barreto Too Ill To Draw The New Yorker’s Anniversary Cover Winner of the Gold Stanley in Australia New Chicago Comic-Con Dennis the Menace Toned Down EDITOONERY Matt Wuerker Gets the Herblock A FEW OF COMICS HISTORY’S BLACK CARTOONISTS Morrie Turner, Ted Shearer, Ray Billingsley, and Milton Knight ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY More of the Usual Nonsense And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go— STAY TOONED! Just heard that the fifth issue of John Read’s Stay Tooned! is now out and about. This issue features profiles of Mort Walker (Beetle Bailey), Jack & Carole Bender (Alley Oop), editorial cartoonist Jeff Koterba, caricature artist Joe Bluhm, New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast, and Justin Thompson (webcomic Mythtickle); mini interviews conducted by Scott Nickel with Alex Hallatt (Arctic Circle), Sandra Bell-Lundy (Between Friends), Stephanie McMillan (Minimum Security), Stephanie Piro (Six Chix), and Terri Libenson (The Pajama Diaries); a report on the recent USO-sponsored NCS cartoonists tour to the Mideast; plus articles/columns contributed by Tom Richmond, Bill Janocha (who also drew the cover), Don Hagist, John Hambrock and moi, your keyboard man here at Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer. To order you very own copy, beam up to staytoonedmagazine.com —just a mere $9, plus $2 p&h. OUR NONEXISTENT LIBERTIES How the Gestapo Works in the United States of America Do you know that you can be thrown in jail if your comics collection includes any

pictures of young people—perhaps “children”; yes, some young people are young

enough to be called “children”—in positions suggesting they are engaging in sexual

activity or are about to engage in sexual activity? If you are a scholar studying various

kinds of manga, you risk your liberty—particularly if, among the manga you are

studying, there are lolicon, manga in which childlike female characters are depicted in

an erotic manner. Pictures, perhaps, like these. In short, do you know that your private proclivities—if they have anything to do with sex—endanger your freedom? That you have, in effect, no privacy whatsoever? That is the lesson we must derive from the case of Christopher Handley, the 39-year-old Iowan with manga in his comic book collection, who was sentenced on February 10 to six months in jail and five years probation because someone thought a minute portion of his collection was “child pornography.” Here’s the February 12 report from ICv2, a report that should send chills up and down your spine. I’ve boldfaced and italicized the particularly outrageous affronts to personal liberty that are manifest in this stunningly gestapo action: ***** Christopher Handley was sentenced Wednesday, February 10, to six months in the federal prison system for “possession of obscene visual representations of the sexual abuse of children,” (i.e., manga). The judge asked that the “Defendant be considered for placement at a community correctional facility or if that is not available, placement at a medical security facility so that Defendant’s medical needs can be adequately met.” The jail time will be followed by three years of supervised release on that count. During the supervised release Handley is to participate in a treatment program to include psychological testing and a polygraph examination. Handley was sentenced to five years of probation on the “mailing obscene matter” count, which will run concurrently with the supervised release to the degree the sentences overlap. The sentence also included a $200 forfeiture, and the forfeiture of the manga and the computer used to order them. The elements above were all agreed to by the defense and the prosecution and presented to the judge as a joint sentencing recommendation. There was no requirement in the sentence issued by the judge that Handley register as a sex offender, nor was there a requirement in the sentence that he stay away from children. Three counts were dismissed at the request of the prosecution based on the plea agreement. The U.S. Attorney described Handley in his sentencing brief in a way that could probably describe many manga fans. “His primary means of social interaction with others has not been involvement in the community, but has been playing online role-playing games,” the brief said of Handley. “Mr. Handley recognizes that these hobbies have been a compulsion, causing him to incur ‘significant debt from buying various Japanese art forms’ and ‘upgrading his computer system.’” The sentencing brief also described the results of a psychological exam of Handley. The prosecution’s sentencing brief listed the seven manga that were in the package intercepted by the postal inspector [RCH: See Opus 239 for the description of this outrageous invasion of privacy]: Book 1) “unfinished school girl” (presented by TAMACHI YUKI) (LE Comics); Book 2) “I ! DOLL” (MAKAFUSIGI presents) (Seraphim Comics); Book 3) “for ESSENTIAL 3" (THE ANIMAL SEX ANTHOLOGY Vol.3) (Izumi Comics); Book 4) “NEKOGEN, Neighboring House Family” (MD Comics); Book 5) ISBN4-89465-172-6 (No English language title found) (Seraphim Comics); Book 6) ISBN4-89465-222-6 (No English language title found) (Seraphim Comics); and Book 7) ISBN4-89465-193-9 (No English language title found) (Seraphim Comics). The prosecution argued that comics were worthy of the same prosecution as real depictions of sex acts involving children: “Some may argue that the crime at issue is not serious because no real children were involved. Such a viewpoint is short-sighted because it gives little weight to the nature of obscenity crimes, in general, and to the specific images involved in this case. A picture, proverbially, paints a thousand words, and there is no doubt that comic books, graphic novels, and works of manga and anime have a powerful ability to communicate through their use of dramatic imagery. Since the 1960s, the genre of comic books has been transformed from a target market of younger customers to a broad, word-wide market aimed at older, more mature consumers. The ground-breaking graphic novel, Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons was even named by Time magazine of one of its top 100 novels of the 20th century. The power of the illustrated story should not be short-changed.” [RCH: The last sentences, ostensibly “explaining” how short-sighted it is to ignore drawings of sex acts involving children, does not, actually, explain any such thing. But it does reveal that the commercial and artistic success of comics as a literary genre has become, in the twisted mind of this legal pervert, a lever by which some unsuspecting citizen can be pried from his fundamental liberty. What kind of a country are we living in?] The prosecution notes, as the defense does in its brief, that there are no analogous cases to use for sentencing guidance because is the first time that comics (or other not-real depictions) have been prosecuted as a federal crime under the new statute. The defense counsel’s brief noted that no actual pornography was found in Handley’s home or on his computer, and that the lolicon material was “only a minute portion of his entire collection, which consisted of tens of thousands of manga and anime, representing all genres of the art form.” The defense said that Handley was aware of a recent Supreme Court decision. “He didn’t know that these books were illegal—they were just drawings, after all, and the Supreme Court had recently held a statute outlawing ‘virtual’ child pornography to violate the Constitution, a fact of which Mr. Handley was aware,” the brief said. Handley did not know, however, that Congress had passed another law banning the same materials after that decision, which it deemed more likely to pass constitutional muster. Since this case was pleaded out, we won’t know whether that’s the case until a defendant willing to take the matter to trial is charged. In addition to the legal and other arguments the defense made in its brief, it also provided a group of character references of Handley. We’ll wrap up our account of this sad day with the final paragraphs of the letter from Michael Snavely, Sr., a friend of Handley’s. “Regarding this case, I am personally unable to understand the reasoning and justice behind the criminalization of the act of reading a comic book that contains objectionable sexual material. This is especially hard to understand when other more heinous material permeates our society and has not been criminalized. “Murder, for instance, is glorified and portrayed with real humans in movies. If it is true that a person is likely to commit the crime of child molestation merely because that person has been looking at drawings depicting that act then why is it not a crime to watch movies or look at drawings of murder? Murder is considered a more serious crime, is it not? I fail to see the reasoning behind the criminalization of the lesser and not the more serious. “It is therefore my opinion that Chris has once again taken responsibility for an act even when the criminality of that act could not have been known to anyone not in the legal profession. How is one to know whether or not a particular drawing is obscene? Who determines what obscene is? The term would surely vary depending on region and religious upbringing of the people attempting to define it. “I am truly sorry that Chris has been the victim of such a pitiful legal defense and lawmakers attempting to legislate morality. It is my hope that you will also see the injustice of this situation. I fully trust and expect you to carry out your responsibility to ‘we the people’ and do what is right.” ***** “Murder is considered a more serious crime, is it not? I fail to see the reasoning behind the criminalization of the lesser and not the more serious.” Snavely can’t see the reasoning because reason does not enter into such situations. Murder is not sex; but sex is sex. And sex, without much question, is responsible in this country for the propagation of more injustice per square foot than just about any other human knack with the possible exception of racism. As a nation, we have a decidedly confused (perhaps insane) attitude about sex and obscenity. Our bewilderment is probably rooted in a misbegotten sense of morality fostered by our Puritanical religious heritage, which successfully proclaimed, without a basis in any fact about human nature, that sex is bad or nasty or wrong, somehow, which leads, inevitably, to the sort of confusion Butch Hancock, a songwriter, discovered as a boy growing up in Texas: “Sex is the most awful, filthy thing on earth, and you should save it for someone you love.” Our attitudes are alarmingly contradictory, as Hustler publisher Larry Flynt memorably points out: “Murder is a crime; writing about it isn’t. Sex is not a crime, but writing about it is. Why?” Despite our aversion to sex in any form, we exploit our relentless interest in it. Said sociologist Philip Stater: “If we define pornography as any message from any commercial medium that is intended to arouse sexual excitement, then it is clear that most advertisements are covertly pornographic.” Stephanie Black, head of marketing at the Playboy channel, adds: “On tv you can use sex to sell anything except sex.” In our attitudes about sex, we are unique in the world, as Marlene Dietrich, an undeniable expert, observed: “In America, sex is an obsession; in other parts of the world, it is a fact.” The law Handley was charged with breaking is a highly questionable matter itself. Section 504 of the PROTECT Act, designed to stop trafficking in child pornography, prohibits distribution or possession of “a visual depiction of any kind, including a drawing, cartoon, sculpture, or painting” that “(1) shows a minor engaging in sexually explicit conduct; (2) is obscene; (3) depicts an image that is, or appears to be, of a minor engaging in graphic bestiality, sadistic or masochistic abuse, or sexual intercourse, including genital-genital, oral-genital, anal-genital, or oral-anal, whether between persons of the same or opposite sex; and (4) lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” Attorney Eric Chase, acting in some capacity on Handley’s behalf, successfully petitioned a district judge to rule the last two clauses unconstitutional because they restrict free speech. I fail to see how picturing a minor engaged in sexually explicit conduct (1) is any less a restriction of free speech than picturing a minor engaged in graphic bestiality etc. (3); it seems to me that if the last two clauses restrict free speech, so do the first two. The dubious judicial determination here is an affront to common sense and probably indicative of the unconstitutionality of the entire law. But the judge let the first two charges stand, so Handley went to trial, charged with possessing an obscenity and/or a visual depiction showing a minor engaged in sexually explicit conduct. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund did not provide the defense for Handley, but was a special consultant to Handley’s defense team, providing access to First Amendment experts, recommending expert witnesses on manga, and funding expert research for an eventual jury trial. "Handley's case is deeply troubling, because the government is prosecuting a private collector for possession of art," said CBLDF Executive Director Charles Brownstein last spring. "In the past, CBLDF has had to defend the First Amendment rights of retailers and artists, but never before have we experienced the Federal Government attempting to strip a citizen of his freedom because he owned comic books.” Putting the case into context, Burton Joseph, CBLDF's Legal Counsel said: "In the lengthy time in which I have represented CBLDF and its clients, I have never encountered a situation where criminal prosecution was brought against a private consumer for possession of material for personal use in his own home.” The gestapo may be knocking on your door next. ***** We discussed the Handley case and some of its implications in Opus 239; Opus 243 reports Handley’s plea bargain and extends the discussion started in Op. 239. I urge you to read both again. It will make you shudder. Handley sounds like a man whose hobby has taken possession of him in ways that are scarcely healthy (and he probably realizes this, hence his plea bargain), but that is neither here nor there. His privacy was invaded, his freedom to be whatever he wanted to be as long as it didn’t infringe upon the liberties of others was ignored. It could be you or me. Manga are on sale in major book stores; and lolicon may lurk among them. Here’s what you can find about lolicon on the Web at Wikipedia: ***** Lolicon, also romanized as rorikon, is a Japanese portmanteau of the phrase "Lolita complex.” In Japan, the term describes an attraction to young girls, or an individual with such an attraction. Outside Japan, the term is less common and most often refers to a genre of manga and anime wherein childlike female characters are depicted in an erotic manner. The phrase is a reference to Vladimir Nabokov's book, Lolita, in which a middle-aged man becomes sexually obsessed with a 12-year-old girl. The equivalent term for attraction to (or art pertaining to erotic portrayal of) young boys is shotacon. Some critics claim that the lolicon genre contributes to actual sexual abuse of children, while others claim that there is no evidence for this, or that there is evidence to the contrary. Although several countries have attempted to criminalize lolicon's sexually explicit forms as a type of child pornography, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, the Philippines and Ireland are among the few to have actually done so. Also, there’s this: Generally, lolicon is a term used to describe a sexual attraction to younger girls, or girls with youthful characteristics. In other words, it can refer to actual or perceived pedophilia and ephebophilia. Strictly speaking, Lolita complex in Japanese refers only to the paraphilia itself, but the abbreviation lolicon can refer to an individual that has the paraphilia as well. Lolicon is a widespread phenomenon in Japan, where it is a frequent subject of scholarly articles and criticism. Many general bookstores and newsstands openly offer illustrated lolicon material, but there has also been police action against lolicon manga. There are also stores that specifically target the lolicon audience. The consumers are said to be white-collar workers in their 20s and 30s who do not complain about the high prices of lolicon merchandise such as figurines and accessories. ***** RCH again: Because so much manga features characters with childlike faces, any of those stories that edge into the realm of romance (the kinds of books teenage girls are grabbing up by the bushel) could be seen as lolicon—or, in this country, child pornography. The gestapo has the ammunition; it lacks only the impulse and the opportunity. NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits In his Cup of Joe feature at comicbookresources, Marvel editor-in-chief Joe Quesada apologized for a scene in Captain America No. 602 that, Fox News alleged, “seems to be a clear effort on someone’s part to undermine the Tea Party movement.” The scene depicts a street protest in which a sign has the slogan “Tea Bag the Libs Before They Tea Bag YOU!” Quesada said that the letterer borrowed the slogan from an actual sign held at a protest he found depicted on the Web. Unhappily, the protest in the story wasn’t supposed to have anything to do with the Tea Party movement, according to Quesada. The mistake provoked what Fox News described as “a chorus of critics who noticed the apparent jab at the Tea Party movement and who accused Marvel of making supervillains out of patriotic Americans.” Quesada said that Marvel has an editorial policy that “Our books are no one’s soapbox,” when it comes to political issues. “I have always made it a point never to publicly talk about my own political beliefs as I don’t feel it’s my place to do so and use Marvel as a bully pulpit,” he said in Cup of Joe. “Our readers come in many shapes and sizes, and we need to be respectful of that. Yes, we have characters that have certain attributes built into them, like political beliefs and religious affiliations, but we try to handle those as carefully as possible, and when we present one side of a coin, I encourage my editors and creators to fairly show the other side.” The art for the Captain America story has been scrubbed, Quesada said, so that any future printings of the story will not include the sign. Maybe, as the wag posting this story concluded, the best news about all of this is that comics are in the midst of a current political discussion, a sign of significant cultural relevance. Mebbe, but I doubt anything about the Tea Baggers can be interpreted as an advance of any sort, cultural or political or, even, comical. RECORD PRICES CLIMB INTO STRATOSPHERE We used to ask each other, fanboys all, who would win in a show-down fight: Superman or Captain Marvel? Later—the Hulk or the Thing? And back in the 1970s, Superman faced Spider-Man in a historic cross-over. (Guess who won that one.) Yesterday, Thursday, February 25, we learned, much to our amazement, that in a confrontation between Batman and Superman, the one without superpowers won: Detective Comics No. 27, the one in which the Cowled Crusader debuted in the spring of 1939, was sold at auction for $1.075 million, $75,000 more than Action Comics No. 1 went for three days earlier. On Monday, February 22, everyone was agog with the news that the “Holy Grail” of collectible comic books, the first issue of Action Comics, which introduced the world to Superman in the summer of 1938, covered dated June, sold in New York for $1 million. The names of neither buyer nor seller were made public by ComicConnect.com and Metropolis Collectibles, which conducted the sale. The buyer already has a copy of Action Comics No. 1 but wanted to upgrade to a better quality book: according to a report from Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs.com., the buyer’s new possession rates 8.0 on the valuation scale, the “second-highest graded copy” of only about 100 copies of the comic known to exist,” said Vincent Zurzolo, Metropolis co-owner. "It's phenomenally beautiful," he said. "I've been in this business for over 20 years, and when I had my hands on this book [recently] for the first time, it was like holding the Holy Grail. ... The brightest tones of white are [amazing] and the spine is gorgeous." Well, if spines turn you on, Zurzolo is the guy to see. Zurzolo’s partner, Stephen Fishler, is more ecstatic about money than anatomy: "They said it couldn't be done,” he trumpeted on the company’s website. “They said that no comic book—no matter how rare— would ever sell for $1,000,000. This week, they were proven wrong. And in the midst of a recession, no less!" Fishler could celebrate for only a couple days: once the barrier had been breached, the wall came tumbling down: in Dallas, Reuters reported, Heritage Auction Galleries sold Batman’s first appearance for more than a million. Shirrel Rhoades, former publisher and executive vice president of Marvel

Comics, said high sales for those comics is likely a direct consequence of the poor

economy—a result not an anomaly. "When the stock market is down,” he said, “when

real estate investments are over the cliff, collectibles offer an alternative that you can

invest in that may have some growth potential." Rhoades added that Action Comics No.

1 is arguably more historic than the first appearance of Batman, but that this week's

sales seem to be following their own logic. "We're probably seeing a little bit of a

feeding frenzy," he said. "With the sale of Action No. 1 for a million, I think that's going

to keep prices up for awhile." ***** In early February, E.W. Scripps announced that it is "exploring strategic options" for United Media Licensing, the character licensing arm of its syndicate United Media, which distributes such comic strips as Peanuts and Dilbert. Spokespersons denied that Scripps is seeking to sell, saying, "Among the possible outcomes of the exploratory process are a sale or joint venture involving all or part of United Media Licensing.” It also might keep the business "if the exploratory process leads management to determine that more long-term value can be created for company shareholders by retaining the property.” Called by a Maryland newspaper one of the "biggest scammers" of 2009, Steve Geppi has money troubles galore. Numerous financial clouds still hang over various of his businesses other than Diamond Comics Distribution, which, so far, seems able to limp along. As summarized by Heidi MacDonald earlier this month (at comicsbeat.com), Geppi owes the printer of his dormant Gemstone line of books ($373,000) and the PNC Bank over a bad real estate deal in Camden, Maine ($16,466,000), but after not paying rent for 19 months at his Entertainment Museum in Baltimore, his landlord reduced the total due by 31 percent, and Geppi paid about $365,000. Meanwhile, law suits abound: $500 million for breach of contract brought by the relatives of Bob Montana, creator of the Archie gang, over some unspecified malfeasance with original art, and $200,000 in rent due a movie theater. Said MacDonald: “As we like to point out every time we run one of these stories, Geppi's interests are set up with separate corporations for his various businesses, so Diamond is seemingly not directly liable for any of these debts and bad business deals. However, Geppi's personal finance problems can't be helping Diamond as they deal with the general downturn on the economy, the not-as-bad-as-everyone-else-but-still-not-good slip in comics sales, and the disaster that was the move to the new distribution center last year — coming at the height of the recession, it left orders in shambles for months. While Diamond is still getting business done, in light of this growing list of debts, the rest of Geppi's empire looks pretty shaky.” In a major adjustment in the Omaha World-Herald’s "Living" features section, the paper is dropping a baker's dozen of venerable comic strips, and replacing them with four newer strips plus more locally-oriented content. Continuity strips took a major whack, Editor & Publisher noted: Gil Thorp, Mary Worth, Rex Morgan, Gasoline Alley, and Prince Valiant are out. Ditto such durable favorites as Cathy, Drabble, For Better or For Worse, Non Sequitur, Andy Capp, Sally Forth, Hagar the Horrible, Dennis the Menace and Shoe (although both these last will continue on Sundays). The new strips—described as “funny and cutting-edge”—are Get Fuzzy, Between Friends, Fort Knox, and The Flying McCoys. "Change among our comics is years overdue," explained Executive Editor Mike Reilly. "Many of the comics we dropped no longer are drawn by the same person, a relative or even an apprentice. The comics have drifted—in their story lines, character development, story pace." There are budgetary reasons as well, Reilly told readers: "Some of these older comics are rather expensive." Eduardo Barreto, who has done such a magnificent job drawing Judge Parker and showing how today’s cramped comic strip space can be deployed to great effect, is giving up the strip because he is too ill too often with meningitis to continue it. John Heebink (as I understand it) filled in for a month or so; his temporary gig will end March 14, and on the 15th, Mike Manley will start drawing the strip. I’ve admired Manley’s work, and I scarcely think his arrival represents any sort of step down—although it remains to be seen whether he can do the sort of eye-enthralling layouts and compositions Barreto did. Said Brendan Burford, comics editor for King Features: “All of us at King Features are sad to see Eduardo go: he gave the strip a classic look with a contemporary edge, and he drew the strip with great passion and professionalism. Mike Manley’s work has great verve and panache, and we’re confident that his stunning compositions and slick line will win over the Judge Parker readers. During his career in comics and animation, Mike has worked on great titles like Batman and Superman, and we feel fortunate that he’ll be filling the role of Judge Parker artist – the readers are in for something special.” That’s all hype, of course, the kind of thing we must expect from a marketing enterprise. But I agree with most of it, and I look forward to seeing Manley make the grade. ***** The anniversary issue of The New Yorker usually (for over 75 of its 84 years) reprinted the cover drawing by Rea Irvin in which a bored-looking boulevardier (subsequently christened Eustace Tilley) inspects a passing butterfly through his monocle. Tiresome, maybe, but Lee Lorenz, long-time cartoon editor for the magazine, once told me they repeated the stunt year after year because they couldn’t think of an appealing alternative. When Tina Brown took over the magazine in the 1990s, she tried different ceremonial images: R.Crumb’s modern slacker version of Irvin’s Eustace Tilley; a female Tilley (Eustacia). Then the magazine got its groove back, reverting to its well-worn rut. Tilley was back on the cover of the anniversary issue for the next several. However threadbare some thought it, I, a creature of habit and custom, applauded, every year greeting Tilley warmly as if he were a long-lost fraternity brother or a fondly recalled crazy uncle. But the most recent variation on the Eustace Tilley theme was pretty nifty—different without consigning Irvin’s icon to limbo forever. In 2008, Seth envisioned Tilley as a playing card, upside and downside. And this year, the magazine’s art editor, Francoise Mouly, commissioned four different covers—each a vignette in the “story” of Eustace becoming a model for the cover. You can find all four at newyorker.com or in the magazine dated February 15 & 22. Christopher Borrelli at the Chicago Tribune made a big deal out of three of the four cover artists being from Chicago, saying that if you’re a Chicagoan and suffer “a Midwestern nag of inferiority” to the Big Apple, you could take comfort and even a kind of satiated vengeful pleasure at the “victory” represented by Chicago artists gracing the anniversary issue of the magazine named after the Windy City’s most obnoxious metropolitan rival. The winning artists— Daniel Clowes ("Ghost World") was born and raised in Chicago although he now lives in Northern California; Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth) lives and works in Chicago’s Oak Park; and Ivan Brunetti ("Schizo") lives in Chicago and is an assistant professor of art and design at Columbia College. Only illustrator Adrian Tomine ("Optic Nerve") lacks Chicago roots. (He lives in Brooklyn.) “Take that, New York!” crowed Borrelli. Then he phoned Mouly to report his discovery. "Ah, you found the hidden subtext!" she joked in response. "But in a way, it wasn't unintended. I wanted artists with an affinity for each other, who appreciate each other, and with Chris and Ivan, at least, I was very aware they are good friends.” So much for the conspiracy theory. Then Borrelli talked to Brunetti. Alas, another disappointment: "You're right,” said Brunetti, “—three guys from Chicago. I hadn't thought of that. I thought 'four guys from alternative comics' — four guys who are not only friends but cartooning idols. We worked together on it. It was an honor. But I'm the Ringo." What do the Beatles have to do with it? ***** Speaking of venerable magazine venues for cartoons, the March issue of Playboy prints two pages of Eldon Dedini, eight cartoons with his panting satyrs and breathless wood nymphs whose plump nakedness made Hugh Hefner famous. THE AUSTRALIAN REUBEN Down under at the 25th annual Stanley Awards convocation of the Australian

Cartoonists Association, held November 12-15, freelancer Peter Broelman was named

Cartoonist of the Year, winning the coveted Gold Stanley, a convoluted statuette that

reproduces in three dimensions a Stan Cross cartoon deemed the funniest ever in that

nation. (It’s the Australian equivalent of this country’s Reuben.) On Obama’s election: “I don’t like changes of administrations because I have all my villains in place, and then they are taken away and replaced with faceless wonders nobody knows. You need villains to get yourself angry.” His favorite villain? “Dubya without a doubt. He was the worst President the U.S. has ever hand. Everything he attempted was a disaster. He was always trying to impress his father.” Are there any villains he regrets attacking? “Bob Dole. I wish I hadn’t, he’s actually a very nice man. I avoid meeting politicians because I’m liable to end up liking them [which is no way for a political cartoonist to function: “You’ve got to bring yourself to the boil once a day,” Oliphant remarked, “—it’s good for you”]. That’s one reason we moved to Santa Fe: you just don’t know who you’re going to bump into in the street in Washington.” Does he still feel Australian? Deep down? Said his wife Susan: “He’s well and truly American now. People are surprised to learn he was originally from Australia.” *That’s the current issue, mate: when it’s winter up here, it’s summer down there. NEW CHICAGO-CON The curtain will rise on a new comic convention in Chicago, April 16-18, at McCormick Place. C2E2, short for the Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo, will unfurl the usual panoply of comics, movies, television, toys, anime, manga and video games plus the exhibition, panel presentations and autograph sessions, giving fans a chance to interact with their favorite creators and to screen sneak peeks at forthcoming movies and tv shows. The show is being put on by Reed Exhibitions, which calls itself “the world's largest event organizer” and also runs the New York Comic Con, New York Anime Festival, BookExpo America, the London Book Fair, the Tokyo International Book Fair, and MIPCOM. Reed's publishing branch is responsible for magazines including Variety, Publishers Weekly, Video Business, and Playthings. The Wizard Chicago-con, until now the only comics and collectibles and pop culture show in the Toddlin’ Town, has moved into August (19-22), perhaps to distance itself from its new rival. Last year’s Wizard Con was somewhat lame, creating the opening that Reed’s new C2E2 aims to fill. We’ll see. Comic-cons are sprouting like spring crocus. Here’s a list, by no means complete, culled from the Comic Buyer’s Guide’s annual Convention Supplement; in chronological order: February 26-28: Steel City Con, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania March 12-14: MegaCon, Orlando, Florida April 2-4: WonderCon, San Francisco, California April 10-11: Boston Comic-Con, Boston vicinity* April 16-18: C2E2, Chicago, Illinois April 23-25: Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention, Barrington Hills, Illinois February 26-28: Steel City Con, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania May 2: Tampa Comic Book & Toy Convention, Largo, Florida May 14-15: Motor City Con, Detroit vicinity* June 18-20: Florida Super Con, Miami, Florida July 22-25: Comic-Con International San Diego, California August 6-8: Steel City Con, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania August 8: Tampa Comic Book & Toy Convention, Largo, Florida October 16-17: APE (Alternative Press Expo), San Francisco, California November 7: Tampa Comic Book & Toy Convention, Largo, Florida December 3-5: Steel City Con, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania * Probably the con is not, actually, in the city named in the con’s title; the ads in CBG’s booklet sometimes hide such information. For more information on any of the foregoing, google the con name. ***** If you noticed in Rhymes with Orange during the week February 15-20 a crisper, more purposeful rendering than the typical languorous scrawl, that’s because when the usual author of the enterprise, Hillary B. Price, traveled to Cuba in January on a cultural and art exchange, she invited award-winning children’s book author, illustrator and animator Mo Willems to take over drawing her comic strip during her absence. Signaling the change, the title of the strip was altered in the opening panel to “Rhymes with MOrange.” Asked in the King Features news release why she selected Willems as her stand-in, Price replied: “I met Mo because he lives in my town. I’m a huge fan of his work, so I pitched him on the idea – and he actually fell for it.” Willems’ books, animated cartoons, children's books, and television writing have garnered six Emmy Awards, three Caldecott Honors, two Geisel Medals and two Carnegie Medals for film. On Monday February 22, Price was back. So was her enviably languorous scrawl. ***** When I saw the headline that Dennis the Menace is being given a new “less violent” make-over, I wondered, “What the —?” Then, reading further, I realized that the Dennis the Menace in question is the British Dennis, who appears in a comic strip in the comic magazine Beano. Last year, we heard via newkerala.com, “rumours abuzz that character of Dennis and his faithful dog Gnasher were being ‘toned down’ in the cartoon,” but the Beano staff dismissed the reports, calling it "another political correctness gone mad" myth. But, as we read further, we saw that Dennis is, indeed, being toned down. Dennis appears in a tv animated cartoon as well as in Beano, and broadcast rules prohibit the juvenile terror (a rampant bloodthirsty schoolboy vandal in the print version) from deploying his killer slingshot and peashooter on the air. So changes were made to the print version so it would match Dennis and Gnasher on the telly. "It was felt we should have Dennis looking the same in the comic as he does on tv to stop people getting confused,” elucidated Beano features editor Claire Bartlett Well, that’s a relief. Hank Ketcham’s creation on this side of the pond can forge ahead, un-toned. Not that any toning-down is needed here: for years, his Dennis has been more mischievous puppylike than vandal. ***** Last year, 110 journalists lost their lives in the line of duty. Most of them, 55, in Asia, “the most lethal region of the world” saith the Denver Post’s article; second place with 28, Latin America. Surprisingly, only 6 died in the Middle East—four in Iraq; in 2008, 14 journalists were killed in Iraq. Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, comicsdc.blogspot.com and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE Justice John Paul Stevens dissented from the Supreme Court’s recent decision to permit corporations to fund political campaigns, saying: “Under the majority’s view, I suppose it may be a First Amendment problem that corporations are not permitted to vote, given that voting is, among other things, a form of speech.” Writing on the same subject in the Washington Spectator, Craig McDonald and Andrew Wheat observe: “The decision nullifies the 1907 Tillman Act, which banned corporate political spending, and topples like dominoes a raft of subsequent federal statues and legal opinions that had insulated political campaigns from corporate cash. With the stroke of a pen, the justices also invalidated all state laws prohibiting corporate expenditures to support or attack candidates for state office.” **** Elsewhere: Champion Olympian snowboarder Shaun White was ahead on points after his first pass through the half-pipe; he had the Gold and didn’t need to make a second run, but he did anyway, saying: “I didn’t come all the way to Vancouver and not to pull out the big guns”—namely, his signature trick, the Double McTwist 1260. And when he nailed this impossible stunt, clocking even more points to beat even his own previous tally, he said: “It was the savvy thing to do. Saucy. Keep it weird.” When a reporter asked him if it was as easy to do as he made it seem, he said: “When you say ‘easy,’ I think the immediate response is: it wasn’t easy in the slightest.” Saucy. Right. EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted Ed Stein, until a year ago the editoonist at the now defunct Rocky Mountain News,

withdrew into the blogosphere where he posts his cartoons and accompanies them with

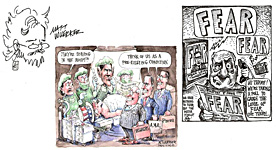

some acerbic prose observations on the passing political scenery. MATT WUERKER HERBLOCKED Matt Wuerker, editorial cartoonist for Politico, was named the winner of the 2010 Herblock Prize on February 17. Awarded annually by The Herb Block Foundation for "distinguished examples of editorial cartooning that exemplify the courageous standard set by Herblock," the winner receives a sterling silver Tiffany trophy and $15,000 after-tax cash award. In a Politico news release, Editor-in-Chief John F. Harris congratulated Wuerker for being “at the top of his game and enjoying it more than ever at a moment when his work matters more than ever,” adding: “Wuerker is funny — the essential prerequisite for a cartoonist. But his cartoons work for other reasons. He assumes and appreciates the intelligence of his audience and never forgets, even when his subjects do, the spirit of public interest that should animate the work of important people in Washington.” Wuerker’s cartoons have been a Politico signature since its launch three years

ago, appearing individually in the newspaper and online, as well as in art accompanying

enterprise stories from Politico journalists. “Herb Block is such a giant in the quirky inky universe of cartooning," said

Wuerker to Mike Cavna at ComicRiffs."When I was in the sixth grade or so, it was a

book of Herblock's cartoons that first flicked on a little light in my head illuminating the

very unlikely career path of the political cartoonist. To get this honor in his name almost

50 years later is truly mind-boggling." Speaking online directly to his colleagues, Wuerker said: “Thanks everybody.

There are so many of you ink-stained wretches equally and richly deserving this. We all

know that these prizes are ultimately somewhat silly exercises in comparing apples with

oranges, lumpers with splitters, hatchers with pixelers ... that eventually ends with a dart

being thrown at a board. I feel absurdly fortunate to get singled out like this. I was joking

about now getting to wear a tiara around the office, but then Richard Thompson told

me, ‘No, with the Herblock, instead you win Speaking for myself, I’m delighted to see Wuerker get this award. His muscular cartoons, bristling with coarse-grained crosshatch, are almost always sharply pointed and unflinching. And in a day when full-time staff editorial cartoonist positions at newspapers are fast disappearing, it’s soul-satisfying to see a long-time freelancer getting recognition. Before his gig with Politico, Wuerker self-syndicated his cartoons, getting them published in a wide range of periodicals—everything from the monthly newspaper Funny Times to The Christian Science Monitor, The Nation to such mainstream dailies as The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times—but having a home nowhere. He hustled and he hung on, and it paid off, at last, with the Politico job. And now, with the profession’s most prestigious award. Previous winners of the Herblock Prize so far have been Matthew Davies of the Journal News, Tony Auth of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Jeff Danziger of the New York Times Syndicate, Jim Morin of the Miami Herald, Jon Sherffius of the Boulder Camera and Pat Bagley of the Salt Lake Tribune—a worthy company for a worthy new arrival.

***** A kerfuffle erupted in the ranks of the nation’s editorial cartoonists because, on more than one occasion, NBC’s “Meet the Press” host Dick Gregory displayed an editorial cartoon without identifying the cartoonist who drew it. Gregory has used cartoons by Rob Rogers of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and, a few months later, by Mike Keefe of the Denver Post. In neither case, did Gregory say who had drawn the pictures he found so potent. “Too many mainstream media folks treat cartoons like they’re shells found on a beach or forwarded e-mail attachments,” said John Cole, the staff editorial cartoonist at the Scranton Times-Tribune. “They wouldn’t reference a Kathleen Parker or Paul Krugman column without verbally identifying the author, and the same ought to go for cartoons.” Properly chastised, NBC has reformed, reported Atlantic City Press editoonist Rob Torne online (at cagle.msnbc.com). Henceforth, “Meet the Press” will give full credit to cartoonists, according to an NBC spokesperson: “We love cartoonists and cartoons which is why we like to show them on ‘Meet the Press.’ So often they perfectly capture and get to the heart of the matter. Not mentioning the cartoonists by name has been an completely unintentional oversight and we promise we will give them all the credit they deserve moving forward.” Editoonists can’t claim many victories—we’re still in Afghanistan despite months of protests by inkslingers, and the health care reform still languishes, stalled by the Party of No—so this one is worth banging on the drum about.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution After 45 days of therapy, Tiger Woods appeared on tv February 19 and apologized to family, friends, fans and, even, members of the so-called news media who had been invited to listen but not to ask questions. Woods spoke for maybe 15 minutes, then hugged his mother on camera and left. In the inevitable post-event critique, members of the so-called news media displayed their infantile pique at not being permitted to ask questions, of which, they averred, there were many. All of them, I assume, of such burning importance as indicated by the Denver Post’s tv critic in an article published before Woods’ appearance: “What we’ll listen for: Will Woods use the words ‘adultery’ or ‘sexual addiction’? How about ‘sex rehab’? What we’ll watch for: Will Woods’ much-betrayed wife, Elin Nordegren, be there to do the stand-by-her-man pose? Will he wear a wedding ring?” Yup. Really important issues, exactly why, to ensure the reporting of which, we have a free and independent press—a convincing display of just the sort of journalistic professionalism that can concoct all those truly mind altering questions that, for now, must, alas, go unanswered. Meanwhile, at the Philadelphia Daily News, editoonist Signe Wilkinson, as usual

way ahead of the rest of us, captured in a single perfect picture the precise nature of

Our Concern about Tiger.

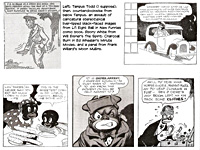

A FEW OF COMICS HISTORY’S BLACK CARTOONERS In Selected Shrifts Both Short and Longish Morrie Turner, Ted Shearer, Ray Billingsley, and Milton Knight As Black History month slips over the horizon for another annum, we pause in our headlong dash to the Next Thing to remember and recognize the marks that some African American cartoonists have made in the medium of newspaper comic strips and elsewhere. Right away, we encountered the most visible fact: invisibility. There aren’t many black cartoonists documented in the general histories of American cartooning. Prowling the Web, we discovered Tempus Todd, a comic strip that started in 1923 and may have been the first strip with an adult male African American protagonist. Until Todd’s advent, most African American characters in cartoons and comic strips had been children, or, if adults, they filled secondary roles as servants or other kinds of menials and fools, importing their imagery and comical conduct from black-face minstrelsy, which is to say, not from actual African Americans but from whites with burnt cork on their faces, “caricatures derived from the popular stage routines of white males’ gross parodies of ‘black life,’ originally the slave life of blacks,” according to Steven Loring Jones in “From ‘Under Cork’ to Overcoming: Black Images in the Comics” at ferris.edu. Tempus Todd, as the star of his own strip, represented, therefore, a marked departure in role if not in portraiture. The strip was written by Octavus Roy Cohen, a Jew from Charleston, South Carolina, who started as an engineer, graduating from Clemson Agricultural College in 1911, but soon turned to journalism, working on several newspapers around the South before deciding to study the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1913 and hung his shingle in Charleston, but when he sold his first short story in 1915, he quit the law and concentrated on writing fiction. I first ran across Cohen in the pages of the Saturday Evening Post, where he achieved some popularity (as well as a measure of notoriety in literary annals) with stories featuring egregious comic stereotypes of African Americans, who spoke an exaggerated “black dialect” that Cohen deployed for comic effect. They were, in effect, still “under cork.” The stories, usually starring a “sepia gentleman” named Florian Slappey, known as the “Beau Bummell of Bumminham,” were handsomely if stereotypically illustrated in gray wash by J. J. Gould, a mainstay at the Post since early in the century. The eponymous Tempus Todd of the comic strip, however, was drawn by H. Weston Taylor, who also did work regularly for the Post. In a 1997 Newspaper Research Journal article analyzing black images in comic

strips, Sylvia E. White and Tania Fuentez say that Tempus Todd’s all-black cast is

depicted “as individuals” and that Taylor “avoided the traditional minstrel face (protruding

white lips, bulging round eyes in a totally black face).” I haven’t seen any more of the

clickingly christened Tempus Todd than the accompanying drawing, which appears at

lambiek.net under Taylor’s name, but with no more evidence than this before me, I’m not

sure I’d agree that Taylor avoided “protruding white lips” and “bulging round eyes”

although Todd, if this is he, doesn’t have the totally black visage and grossly liver-lipped

portrayals typical of the day. Only in black ethnic newspapers did African Americans find themselves in positive, identity-affirming positions in the funnies—the most celebrated, probably, was produced by Harlem’s fabled black cartoonist Oliver Harrington. His Dark Laughter single-panel cartoon first appeared in the Amsterdam News on May 25, 1935, in the midst of the cultural fervor known, later, as the Harlem Renaissance—a flowering of literature and art celebrating the nature of black identity in America that took place, ironically, while the Great Depression was smothering much of white America. At first Dark Laughter’s wry comment on the passing scene north of Manhattan’s 125th Street involved no recognizable cast, but by the end of its inaugural year, a portly, bald moustached and usually mild-mannered man appeared; his friends called him Bootsie, and after his first appearance in Dark Laughter on December 28, 1935, he was in almost all the cartoons, and he became, as M. Thomas Inge has said, “the first black newspaper comic character to achieve a national reputation.” Later, Harrington did an adventure comic strip Jive Gray, whose title character, a World War II ace aviator, was inspired by the real-life all-black 332nd Fighter Group. In this strip, Jones says, “Harrington showed his love of the black persona by filling the strip with creatively colorful black slang (‘jive talk’) and attractive, elongated characters.” (Harrington’s story is more fully explored in Harv’s Hindsight for October 5, 2008.) Another well-known and admired black comic strip character produced by a black cartoonist was Torchy Brown by Jackie Ormes. Torchy had two lives in African American newspapers: in Dixie to Harlem (May 1, 1937 - April 30, 1938), Torchy is a Mississippi teen traveling through humorous escapades to fame in Harlem’s Cotton Club; in Torchy Brown in Heartbeats (August 19, 1950 - September 18, 1954), she is a mature, independent-minded woman whose sometimes harrowing adventures bring her face-to-face with serious issues, like race and international politics and environmental causes. Ormes produced other cartoon features, too (see Opus 219), but all were confined to the pages of the black press. A small but active cadre of African American cartoonists thrived in black newspapers, chiefly those in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh—and I don’t want to overlook Bungleton Green, the most durable of the black press’s comic strip stars, invented in 1920 by Leslie M. Rogers at the Chicago Defender and continued by a succession of five other black cartoonists until 1964. But it wasn’t until after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 that mainstream American newspapers wanted comic strips about African Americans that depicted their characters in affirmative ways.

MORRIE TURNER

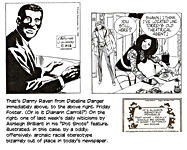

The first of this new crop was an adventure strip, Dateline Danger, that began November

11, 1968. Aping the popular 1965-68 tv series “I Spy,” the strip starred a white-black duo

like tv’s Robert Culp and Bill Cosby: Troy Young and Danny Raven are secret agents

who girdled the globe shooting trouble, their exploits written by John Saunders (son of

the medium’s most prolific writer of comic strips, Allen Saunders) and drawn by Al

McWilliams. The next most ambitious effort was Friday Foster, a soap opera tinged with

occasional espionage intrigues. Written by Jim Lawrence and elegantly rendered by a

Spaniard, Jorge Longaron, the strip began on January 18, 1970 to chronicle the career

of a young black woman (who looked, Ron Goulart avers in his history of the medium, The Funnies, “a good deal like Diana Ross”; I’d Turner, born in 1923, was in the Army Air Corps during World War II, and he drew gag cartoons for base publications—crude artwork, perhaps, but getting printed was an education. “It seemed easy then,” Turner once recalled. “Sometimes it was humor by committee, and a lot of it was so ‘in’ that nobody outside the base could understand it. But I began seeing the power in it. We could dig at some lieutenant, and nobody could do a thing about it.” After his military service, Turner took a job in California as a clerk in the Oakland Police Department and freelanced cartoons to magazines. All the while, he mulled over an idea for a comic strip. Peanuts particularly engaged him, and then once when Charlie Brown appeared in a Civil War cap, Turner pondered: What if Charlie Brown were black? And what if the cap were a Confederate cap? “Now that,” wrote Tom Carter in the Cartoon Club Newsletter, “was indeed a laugh—a child so naive he could sweep away generations of ill will with one innocent, ironic gesture.” Thus, the birth of Nipper. In 1963, Turner developed a strip about black moppets, called it Dinky Fellas and sold it to the Berkeley Post in his hometown and to the Chicago Defender in the Windy City back east. In 1964, with the advice and encouragement of Charles Schulz and comedian Dick Gregory, Turner integrated the strip in the hope of advancing race relations in the world outside it and sold it as Wee Pals, which debuted February 15, 1965. The riots in Watts that summer stalled the strip: newspaper editors were leery of publishing anything that might stir up trouble. But Turner kept on, and in the wake of King’s murder, newspaper editors suffered attacks of white guilt and wanted to increase the representation of black characters in the funnies. Turner’s daily lesson in tolerance was just what was needed to give race relations a human face, and sales of Wee Pals soared: it acquired most of its client list of newspapers within three months of King’s death. In 1974, King Features took on the syndication; these days, Creators Syndicate handles Wee Pals. Every minority (including the handicapped) is represented in the strip, and Turner promulgates a benevolent message of harmony as well as humor. When the Confederate cap wearing Nipper and his racially diverse friends are picking a name for their club, they consider “Black Power,” then “Yellow Power,” then “Red Power,” finally settling on “Rainbow Power”—all colors working harmoniously. “That was two years before anybody ever heard of the Rainbow Coalition,” Turner said. Musing about his craft, Turner added: “Doing a cartoon enables you to step outside and look at yourself. It’s like therapy, and I’ve become a better person for it.” So, we submit, have the readers of Wee Pals. Like most black Americans—and many Americans regardless of race—Brumsic Brandon, Jr. was stunned, angered and saddened by the slaying of Martin Luther King. Born in 1927, Brandon had been cartooning most of his adult life (in animation chiefly) and had been unsuccessfully submitting comic strips (about white people or animals) for syndication since he was a teenager. By 1968, he had been working for twelve years as a designer for the Bray animation studio in New York when he came up with the idea for a comic strip about childhood in a black working-class inner city neighborhood. He named it Luther in tribute to King and sold it to the Manhattan Tribune in 1968; soon, it also appeared in Newsday. Luther is about the same age as Nipper and his pals, but while Turner’s integrated cast was middle-class, Brandon’s strip was set firmly in the ghetto. Jones says “it dealt less with race relations than with the universal human aspects of a child's struggle for survival,” but Brandon, in conceiving and perpetrating the strip, was determined to "tell it like it is,” Jones adds. “Brandon put a ‘message’ in the gag format and created his cast of kid characters with names like ‘Hardcore’ (from ‘hard-core unemployed’), ‘Oreo’ (slang for the person who is ‘black’ on the outside but ‘white’ on the inside), and their never-seen white teacher' ‘Miss Backlash,’” making Luther “the most biting of the strips born in the 1960's.” Biting but not without humor: Luther thinks of the hole in the bathroom ceiling as “open housing.” Luther was picked up for national syndication by the Los Angeles Times Syndicate in 1971.

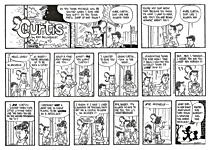

TED SHEARER

Then came Quincy, whose energetic, juicy brushline and lively layouts showed that

comic strip rendering could qualify as high art. Shearer credits famed E. Sims Campbell with setting him on the road to being a cartoonist. He’d seen Campbell’s cartoons in Esquire and in the Amsterdam News and “immediately became inspired.” And when he learned that Campbell lived in New York, he went to see him with a bundle of cartoons under his arm. He rang the doorbell, and Campbell’s wife appeared. “A gorgeous woman, she was very gracious to me,” Shearer remembered for Jud Hurd’s magazine, Cartoonist PROfiles (No. 11, September 1971). “She said she knew that he would see me—although he was a little busy at the moment—and she asked me to write him a note for an appointment. Then a week or so later, I got a card from him, telling me when to come. And this was the beginning of a beautiful relationship. He not only taught me some of the ins-and-outs of the cartoon business but gave me a number of things—knowing that my mother and I weren’t too well off. I recall a drawing light—and even a dog on one occasion!” Shearer went to the Art Students League and took courses at Pratt Institute. When World War II broke out, he found himself in the Army, serving in the 92nd Division; called the Buffaloes, the 92nd was the only segregated division to see action in Europe. In off hours, Shearer drew cartoons about army life and sent them to Continental Features, which marketed them in the states. Tim Jackson, who maintains an encyclopedic website on “Pioneering Cartoonists of Color” in conjunction with his clstoons.com, tells me that Continental Features “was a syndicate created by an African American to distribute to the black press cartoons that featured characters of color, chiefly drawn by African American artists and illustrators.” (There’ll be a section about it and its founder in Jackson’s forthcoming book, Pioneering Cartoonists of Color.) Shearer gained the rank of sergeant and became an illustrator for Stars and Stripes, where he was eventually art editor and received a Bronze Star. Back home after the War, Shearer continued with Continental Features. He

created three single-panel cartoons: Around Harlem about the social life of young black

men and women in the late 1940s, and Next Door and Hill Family, more family oriented

and focused on black families in a big city; they appeared regularly in the Amsterdam

News until Shearer started Quincy. “When I gave my name over the phone in arranging for an appointment, I suppose they figured that ‘Shearer’ was Irish. But when I showed up for the meeting and the receptionist saw me, she went into an inner office and made me sit out in the reception room for an hour. When I finally did get in to see my man, he went through my portfolio in about three seconds and then said, ‘If there’s anything, we’ll let you know.’” He had a similar adventure after he’d sent some cartoons to a religious magazine in Chicago. They didn’t use cartoons, they said, but they liked his drawings and asked him to illustrate a teenage question-and-answer page, one drawing a month. But before he got fairly started, he was invited to a get-acquainted evening being held in Manhattan for New York contributors. “My wife and I worried over the big decision as to whether I should go to the function since I knew the magazine people weren’t aware that I was black. I finally decided to go to the hotel that evening, and though the magazine people were very polite on the surface, I could easily tell from the subtle changes of expression on their faces that my being black had jolted them. As soon as they went back to Chicago, the picture changed: I was told that the teenage project was being phased out—although I’d been told previously that they planned to continue it for another year.” It wasn’t “popular” then for any magazine to be using black talent. Shearer remembered when he sold his first cartoon to a mainstream magazine. “A gal at the Ladies Home Journal bought a drawing of mine. I will never forget that day—from that time on, I was so highly motivated that I could have accepted a thousand rejections in my stride. Then the humor editor of This Week bought something of mine, and I sold a little book to Friendship Press.” Soon he was selling to Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post and other magazines; and King Features often bought cartoons from him for its repertory gag cartoon Laff-a-Day, which featured different cartoonists in irregular rotation. When Shearer approached Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborne advertising agency, looking for assignments, his experience was “just the opposite” of what it had been at that other major ad agency: “I met a delightful guy, Larry Berger, who invited me into his office for a half-hour before he even looked at my things. You can imagine how much I appreciated his offering me a job a little later when I tell you of an experience I had just at that time. My wife and I had a couple of kids and we wanted to buy a house. When I went to the bank to talk to the loan manager, I almost fell off my seat when he looked at me and said, ‘We don’t issue loans to artists, writers, and tap dancers!’” With experience in animation just as television was beginning to infect the daily lives of every American, demanding advertisements in motion, Shearer was hired as television art director, and he stayed with BBD&O for the next 15 years. At the time he was hired, approximately mid-1950s, BBD&O was the most prestigious ad agency in the city. (Those of us pounding the pavement on Look Day at the time used to joke that “Batten, Barton, Durstine and Osborne” was the sound of a trunk tumbling down stairs; the famed investment firm of the day, “Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Beane,” was the sound of the trunk being dragged back up the stairs.) Shearer won five professional awards during his stay at BBD&O, and then in late 1969 or early 1970, he began conjuring up Quincy, prompted by a King Features artist whom he often ran into on the commuter train to Manhattan. Shearer submitted a succession of samples of the strip, and King bought it. Quincy debuted June 17, 1970. (In his entry in the membership album of the National Cartoonists Society, Shearer says the strip started in 1971, but that is mistaken: in the first paperback collection of Quincy, numerous strips dated 1970 appear.) Shearer left BBD&O almost at once. He left because he was eager to fly solo. “I love to draw,” he told Jud Hurd, “and I love the business of being an artist. But in advertising, no commercial or ad results from the effort of any one man. There are too many people involved for that to be possible. There’s the guy who comes up with a germ of an idea—the writer—the art director—the creative chief—the advertising manager for the client—the client—the client’s wife, and so on. On the other hand, in the case of Quincy, I feel a total responsibility for it six days a week.” But he had loved the advertising business, too. “I’m one of the nuts who really enjoyed it. So many people knock it but I never found it hard to get up to go to work. Each day had a new bag of problems because we were always making new commercials. I loved the quickness of the guys involved in advertising—this really turned me on—and how I enjoyed the gassing sessions with them! In advertising, you’re always working with 3-5 other people, whereas I call the strip business ‘the loneliest job in town.’ I was never aware of this difference at BBD&O, and as I’m working on the strip, I sometimes wonder what the guys at the agency are doing at that moment.” About Quincy, Don Markstein at his Toonopedia.com writes: “Most commentators on Quincy agree that Shearer's characters were identifiably minorities in lifestyle as well as skin tones, and often derived gags from the fact, but weren't vocal advocates of change. Mostly, they were just a bunch of kids who got along together and didn't give much thought to their racial identity. Quincy thrived on the comics page,” Markstein continues, “becoming one of a handful of the early integrated strips to survive beyond the 1970s.” Said Shearer: “I’m sometimes tempted to do some preaching in the strip because I’ve been hurt so many times—being a so-called ‘black American’—but I always have to catch myself and realize I’m doing a humor strip and not an editorial strip.” But it was also a question of tactics, Shearer explained: “In the strip, I’m working with a nine- or ten-year-old black child, and no person wants a nine-year-old telling him what to do. It just doesn’t make sense.” Quincy gets off a zinger every once in a while, but mostly, Shearer tried to make his case through more subtle means: “I try to place this nine-year-old and the other characters in an environment in which readers can see the conditions under which these individuals live. By including authentic background drawings [of an inner city neighborhood], I’m making it possible for the reader to come to his own conclusions. I don’t want to turn readers off by becoming preachy. ... Quincy’s lecturing people would be the fastest way to stir things up. My first idea is to get people to like Quincy, to get them involved with the character, and then they can see for themselves the broken-down home, the torn sneakers, etc. Then perhaps readers will say, ‘Gee, maybe we can help.’ Or even the poor white can say, ‘Gee I went through this same thing myself.’” According to comics critic/historian Dennis Wepman in Ron Goulart’s Encyclopedia of American Comics: “Quincy and his buddies are natural, not particularly precocious children, neither mischievous nor sentimentally virtuous. They explore their environment and accept their problems with the serenity and resignation of little stoics, securely at peace in their slum. Quincy’s benevolent Granny Dixon, one of the few adults in the strip, exudes affection and support and provides a positive role model of discipline, love, and fatalism. Gracefully drawn, the realistic treatment of squalor in the crumbling tenements and cracked sidewalks of the backgrounds in Quincy is presented without rancor. Shearer rendered his characters sympathetically, without irony or indignation, and the social and economic problems that afflict them were cheerfully endured in an atmosphere of fellowship and fun.” “The characters in Quincy were delightful,” wrote one unidentified web commentator, “—ordinary children engaged in the everyday joys of young life in an inner city neighborhood. ... There was no wailing about their station in life, no complaining about their situations—just kids having good old kid fun.” And occasionally taking a sharp poke at the residual discriminatory conventions of the outside society. If that sounds a trifle pollyana-ish these days, it was the essence of Shearer’s secret campaign to avoid rocking the boat of bigotry while at the same time drilling a few holes in the bottom in the hope that it would sink. Although the gags seemed authentic evocations of ghetto kids’ attitudes, they were often tepid. But the pictures never were. Whatever the political or sociological impact of Quincy, the strip was undeniably one of the best drawn strips in the nation’s newspapers. Shearer’s liquid line waxed and waned and waltzed through the panels, a symphony of calligraphic variations that the cartoonist accented with artfully spotted black solids and painterly gray tones laid on like watercolor. (As, indeed, they were: when he finished inking a strip, Shearer splashed in a light blue wash to indicate where the syndicate art department should add zipatone dots to create the gray tones.)

But there was more to Shearer’s artistry than drawing technique. The kids in Quincy are always on the move: like kids everywhere, they talk as they walk or run or shoot hoops, and the talk usually has nothing to do with the actions being depicted. And no kid ever moves in the same way as the kid next to him: when Shearer drew three kids walking down the street, each kid has his own body English and perambulates in his own idiosyncratic fashion. That’s pure kid stuff, no question. But I think it came about for reasons arising from an artist’s compulsions not an anthropologist’s. The words carry the joke, and, with the joke out of the way (so to speak), it is as if Shearer could then play with the pictures, and to keep himself interested, he introduces as much visual variation as he can conjure up in what’s left of the panel space after putting in the speech balloons. The result is not just aesthetically pleasing: it also authenticates the life Shearer was portraying by giving it constant, childish movement. And the strip goes beyond mere authenticity in its pictures. Shearer varies panel composition when he doesn’t need to for the sake of the joke; he does it for the sake of visual interest, giving his readers something different to look at in every panel. He gives the dynamic of his pictures torque by shifting camera angle and distance from panel to panel. And the dynamic brings the pictures to life. Quincy and his grandmother and his friends live through the sheer artistic vitality of Shearer’s drawings. Cartoonist Mike Lynch performs insightful analysis of some Quincy strips at his blog, mikelynchcartoons.blogspot.com; look for August 28, 2008 and February 27, 2009. Evidence of Shearer’s masterfully rendered comic strip is available these days in just two pocketbook collections: Quincy, from Bantam in 1972, and Quincy’s World, Tempo Books, c. 1978. Shearer ceased Quincy in 1986. Dunno why. He was 65 (or thereabouts: the year of his birth varies from one account to another), and in those days, people retired when they reached 65. Maybe that’s why he shut down the strip after just 16 years. But he pursued a creative life, continuing to collaborate with his son John in producing a series of children’s books about Billy Jo Jive, which spawned an animated feature on “Sesame Street.” He died December 26, 1992. Cardiac arrest, his son told the New York Times. Luther had expired in June the same year as Quincy. With Dateline Danger and Friday Foster long gone, that left only Morrie Turner’s Wee Pals to represent African Americans in the funnies. Surprisingly perhaps, the dearth of diversity made editors of newspaper comics pages think seriously about how to remedy the blight. It began, according to Dave Astor at Editor & Publisher, when in 1988 the Detroit City Youth Advisory Commission “urged Detroit newspaper editors to do something about virtually all-white comics pages.” Executives at the Detroit News and Detroit Free Press complained to syndicates about the lack of diversity. Cartoonists were urged to introduce characters of color into their mostly white casts. Later that year, “coincidentally or not,” Astor wrote, “several talented African American cartoonists were offered syndicate contracts: Ray Billingsley, whose Curtis began in October 3, 1988; Robb Armstrong, whose Jump Start began the next year, as did Steve Bentley’s Herb and Jamaal.” And Barbara Brandon, daughter of Luther’s creator, launched her Where I’m Coming From, a weekly commentary cartoon with a black feminine point-of-view, in the Detroit Free Press in 1989.

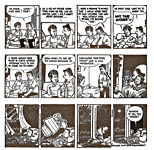

RAY BILLINGSLEY