|

|||||

|

NOUS R US Report on the New York Comic-Con Then: Keith Knight gets a daily strip, Peter O’Donnell regrets at 88, Alan Moore and “The Watchmen” movie, graphic novel publisher jailed in Egypt, Chinese animation, Funky visit to The Birthplace, censorship at “The Simpsons,”Meanwhile nominated for an Eisner, Kemsley’s successor on Ginger Meggs, and— Superhero Summer: peeks at the forthcoming blockbusters

COMIC STRIP WATCH Celebrating Earth Day: Over the Hedge and some oddities

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Anna Mercury and Doktor Sleepless reviewed Classics Illustrated from Papercutz (Great Expectations) and Marvel (Dorian Gray, The Iliad)

BOOK MARQUEE Mammoth Book of Best War Comics The Complete Peanuts, Vols. 8 and 9 The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (Well, it didn’t; not that much) —including a refutation of some of Hajdu’s erroneous thinking The Complete Terry and the Pirates, Vol. 2

GRAFICUS NOVELIS Percy Gloom reviewed

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS R US All the News That Gives Us Fits Big Comics Doin’s at New York’s Jacob Javits Center The New York Comic-Con, on its third outing, April 18-20, registered over 64,000 persons but managed it in much more efficient ways than last year, which left thousands standing on the sidewalks outside, unable to gain entrance to the already packed Javits Center. PW Comics Week reports that although there were 10,000 fans lined up on Saturday morning, waiting for the exhibit hall to open, show manager Lance Fensterman said show personnel were able to get them inside in about 20 minutes once the hall opened. The International Comic-Con in San Diego should take lessons. Fensterman acknowledged overcrowding in program areas of the Center, where sometimes thousands jammed the hallways, particularly when several well-attended sessions adjourned at the same time, but “public safety officials were impressed,” he said, “with the spread of people on the [exhibit] floor and there were no concerns about safety.” Although the Con could use more rooms for panel presentations and more theater space, it will return to Javits next year, February 6-8, in virtually the same space as it occupied this year. Reconfiguring the exhibit hall, said Fensterman, will permit more exhibits, but he didn’t say what might be done with the programming. Thursday

night found Stan Lee, a legend in his own time as co-creator of the Marvel Universe,

accepting the Con’s first New York Comics Legend Award “at

an exclusive party at the Virgin Megastore in Times Square,”

reported Peter Sanderson at PW Comics Week. “Befitting Lee's

stature in the medium,” Sanderson continued, “it took not

one but three speakers to introduce him: comics writer Peter

David, Virgin Comics CEO Sharad Devarajan,

and Marvel editor in chief Joe Quesada.”

The award is intended to honor New Yorkers who have made major

contributions to the comics medium, and although Lee has long been

based in Los Angeles, he was born in New York City and grew up there,

and it was in New York that he did his groundbreaking work at Marvel.

“Noting that Lee had co-created so many world-famous

characters, Quesada kidded him by running down a list of some of

Lee's lesser lights, like the Porcupine, the Living Eraser, and the

monster Googam. Son of Goom. But Quesada concluded that ‘Stan's

greatest creation is Stan Lee,’ the persona that he devised for

himself, which Quesada Lee then arose to accept the Award and to assume the role he had invented, “Spider-Man 3" playing on videoscreens nearby. “As his fans would expect,” Sanderson said, “Lee took neither the award nor himself too seriously. ‘You want to hold that?’ he asked, passing the award to another person on the platform. In mock annoyance, he complained that Quesada had just badmouthed Googam and even the Porcupine: ‘One of my greatest creations! I'm saving him for a movie. I'll never let Quesada talk about me again.’ As for the award, ‘I think I'm very grateful for whatever that was,’ Lee told his amused audience. ‘I have to make some explanation to my wife— You traveled three thousand miles for that? Then Lee told the audience ‘Thanks a million! You've all been wonderful!’ But Lee remained a good while longer, moving through the large room, greeting the delighted fans surrounding him.” At a panel the next day, reported Johnathan Hardick at the Express Times, Lee surprised an adoring multitude of over 600 with the announcement that he is returning to comics full-time as a writer and editor. He will create his first “original comic book characters” in more than 20 years for Virgin Comics. Asked what his biggest challenge might be, Lee said: “I don’t think it will be difficult at all. To me the easiest thing in the world is writing and editing. Editing is easy if I do the writing because I love what I write. I’m a big fan of me.” He’ll pick the artists he wants to work with, Lee added, saying “we have a lot of volunteers” already. As for the new comic books/characters, he has a few ideas: “I had ten that I quickly jotted down but by the time we get to it, [it] will be complete different.” Typical Stan Lee—a flurry of notions, most of which are, doubtless, but half-formed, just the sort of antics that built the fabled House of Ideas (i.e., Marvel Comics, in case you’ve forgotten). “I had something in mind,” he went on, “but when I saw the teaser poster, it was completely different than what I had been thinking. But I find it kind of fascinating, so I may create something new based on the poster.” Sounds exactly like the way he co-created the Marvel Universe: tossed an idea at an artist, then when the artist delivered pages that looked “completely different” than what Lee thought he’d proposed, he created something else with words to go with the pictures. We’ll all wait on tenterhooks here at the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wurlitzer, but I very much fear that Stan Lee’s creative inspirations are still too rooted in the 1960s to work well today: today’s comics audience is much more sophisticated than even his college-age readers were then. But we’ll see. And we’ll keep our fingers crossed. Kai-Ming Cha and Bridgid Alverson at PW Comics Week proclaimed the New York Comic-Con “Manga Country,” adding that “San Diego may host the show with the biggest Hollywood presence, but this past weekend New York showed that it is still book country. With Random House, Hachette, Harry Abrams, HarperCollins and other trade book publishers in attendance,” they continued, “the New York Comic-Con had the feel of a publishing trade show buoyed by charged consumer exuberance of comics and pop culture fans.” But manga was The Presence: “There were big announcements by Viz Media and Del Rey; plans for a new line of color graphic novels by Tokyopop and a new content deal between Japanese publisher Square Enix and Yen Press. ... Viz Media announced a joint project with Stan Lee and Shaman King creator Takei that was launched in Japan over the weekend and will eventually hit American shores. ... [And] Tokyopop launched a new imprint, Tokyopop Graphic Novels, which will be a line of full-color graphic novels by manga-inspired creators from around the world. Publisher Mike Kiley anticipates the line will have cross-over appeal with American comics readers.” But a small cloud has gathered on the sunny manga horizon. At a session on “Emerging Trends in Manga Retailing, panelists argued that “the trend [in comic book stores] is to carry fewer manga titles even as the number of releases steadily increases.” Said James Crocker, managing partner at Modern Myths in Northampton, Mass.: “We used to carry a whole lot of manga until chain stores started selling a lot.” Crocker and his fellow panelists, all operators of comic book stores, haven’t the shelf space to devote to the current flow of manga, and although manga apparently sell well enough in chain stores, they don’t move that well in comic book shops. But the comic book business is clearly growing. According to an analysis conducted by ICv2 and presented at the NYCC, the U.S. retail graphic novel market reached $375 million in sales in 2007, up around 12% over 2006 sales. The periodical comic [comic book] market was $330 million in 2007, bringing the combined 2007 comic and graphic novel market to $705 million for the U.S. and Canada. Comics were up from $310 million the year before; the total was up roughly 10% from 2006 numbers. Graphic novels once again gained share of the business, increasing from a 52% to a 53% of the total. Manga sales were up only about 5%, “the lowest growth rate for manga since ICv2 began tracking sales.” Sales through bookstores were up by a mid-single digit rate, but direct market sales of manga declined 5-10%, “due to a reduced emphasis on the category by comic stores, a significant percentage of whom cut back on manga floor space in response to the growing number of releases and the increased difficulty in choosing between them. ... Another factor in the slowing manga growth rate may have been increased competition from publishers of American graphic novel material for space in stores. American ‘genre’ (superhero, science fiction, fantasy, horror) releases climbed 31% in 2007, to 1268 releases from 965 in 2006, according to the ICv2 white paper. Manga releases also climbed, to 1513 new releases in 2007, up 25% from 1208 in 2006. Over-all, there were 3,391 graphic novels released to the trade last year, according to numbers compiled by ICv2 from release lists provided by Diamond Comic Distributors, up 22% from 2006's 2,785 releases.” Late Saturday afternoon the teaser trailer for Lionsgate Films' forthcoming film “Will Eisner's The Spirit” unrolled in its “world premiere” (as they say in the glitteratti biz) with cartoonist turned screenwriter/director Frank Miller, actress Eva Mendes, and producers Michael Uslan and Deborah Del Prete in attendance. According to an online mtv source, the teaser “fused the look of Eisner's classic comics series with Miller's Sin City movie, as a silhouetted Spirit raced across the rooftops of a film noir cityscape of blacks and grays, accented by the bright red of the Spirit's tie.” The filming of the actors has been completed, but the movie will not be ready for release until early 2009 because of the “long post-production process of creating the computer-generated backgrounds and other special effects, like the Sin City films, adapting to the screen the visual style of the comics artist,” here, both Will Eisner's art style and Miller's own. “Del Prete noted that Miller not only provided copies of Eisner's work to other people working on the film, but that ‘We had Frank there drawing on the set at all times.’” Miller said he loved directing movies, and he expects other comics artists to join the club. "Slowly, steadily, the inmates are taking over the asylum," he said. But Miller is still happy to work in comics. In addition to collaborating with Jim Lee on All Star Batman and Robin, Miller said he’s completed "122 pages of my next graphic novel," the title of which, he said, he could not yet reveal. Neil Gaiman, called these days a “comic book legend,” was on hand to support the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which, reports Jennifer Vineyard at mtv.com, “just won a case that Gaiman has been championing for the past three years”—namely, the sordid Georgia assault on free enterprise and free speech in the person of comic book store owner Gordon Lee, who, as we all remember, was charged with “distributing harmful material to a minor.” The “material” was a comic book that depicted the first meeting of George Braque and Pablo Picasso in the latter’s studio, Picasso being, as he always was when painting, nude. Male nudity is pornographic to Georgians, it seems. But not to anyone else. Said Gaiman: “It manifestly was not pornographic any more than an encyclopedia entry featuring the Venus de Milo.” When, after three years, Gordon Lee’s case finally came to trial last fall, a mistrial was declared due to some malfeasance of the prosecuting armada. At the time, they vowed to bring the case back again this year, but, as Gaiman was happy to announce, the case had been dismissed late Friday afternoon, April 18. “It's cost the fund $100,000," Gaiman said, "and I think it was starting to edge into the millions for the city of Atlanta,” adding that freedom of speech in comics is not treated on the same level as those rights awarded to music, prose, art and movies. "Barely a week goes by before a librarian contacts us saying, ‘They are challenging this Daredevil graphic novel. How do I keep my job and keep this on the shelves?' Comics is just this strange, bastard medium that's thought to be intended for kids, and so it falls between the cracks. If this was prose, there would be no argument, but we're fighting for creators and publishers and retailers—and now librarians—so you're free to read the stuff." And here, to conclude our second-hand reporting on the NYCC, is a piece by Editor & Publisher’s Dave Astor in which, observing the enthusiasm manifest there for all things cartoon, he wonders if newspapers will ever turn that to their advantage. Here it is, verbatim: When Spider-Man creator Stan Lee briefly walked through a lower level of Manhattan's Jacob Javits Center this past Saturday, the comic-book legend was treated like a rock star by hyper-excited fans. I saw the reaction to Lee—who also writes the Spider-Man newspaper comic —just before I participated in a panel discussion on "Comic Strips for the 21st Century." That discussion was one of Saturday's 10 concurrent noon sessions at the New York Comic Con (NYCC), and one of nearly 250 total sessions at an April 18-20 event that also featured exhibits, autograph sessions, and much more. At least 50,000 people attended NYCC, which is only in its third year. San Diego Comic Con—the original event of this type—drew 125,000 people to its 38th-annual gathering last year. In short, comics have a huge fan base. But few newspapers are making much of an effort to attract these devotees. Sure, many comic-con attendees prefer comic books, graphic novels, and animation to newspaper strips—but syndicated artists are among the draws at these events. And syndicated comics would be more appealing to cartoon fans if newspapers stopped shrinking the size of the strips they run. Also, many papers now have fewer comics in their daily pages and fewer pages in their Sunday “funnies.” Some Sunday strips used to run a full page; today, papers often cram six or seven comics per page into smaller Sunday sections. It would also be nice if newspapers' online editions offered more comics—including syndicated and local strips that don't make it into print editions. Some of these comics could be a little more "alternative" than those in print editions if newspapers really want to grab younger readers. Many papers might feel there aren't enough good comics out there to justify a larger print and online lineup. That's debatable, because comics remain a popular part of newspapers despite the cavalier way these papers often treat cartoons. And the quality of newspaper comics might improve if cartoonists knew they were more welcome in that medium. After all, some of the best artists choose animation, graphic novels, children's books, and other outlets when they see what the newspaper world has to offer them. Will many papers increase their comics offerings? Probably not. Newsprint is expensive, feature budgets have shrunk, and many managers are too busy laying off people to worry about the "funnies." Actually, papers could make more money off comics by creatively selling ads next to them while hoping readership of an expanded cartoon lineup helps stem circulation declines. But that would require long-term thinking rather than short-term profit obsession. So while newspapers apathetically cram comics into their pages, cartoon fans excitedly cram into comic cons. Bravo, Dave. If this sort of considered effusion coming at the font of the periodical publishing business, E&P, doesn’t get newspaper editors thinking, probably nothing can. If it ever has.

IN OTHER, LESS WORLD-SHATTERING NEWS OF COMICS AND CARTOONING:

Ollie Johnston, the last of Walt Disney’s “Nine Old Men” (who, at the time their nicknaming, were all young men), his champion animators, died on April 14 at the age of 95, reports Entertainment Weekly (April 25 / May 2), quoting John Lasseter, head of Pixar/Disney animation: “Ollie had such a huge heart, and it came through in all of his animation, which is why his work is some of the best ever done.” ... Free Comic Book Day, Saturday, May 3, is the day after the “Iron Man” movie opens nationwide; no coincidence—this represents a return to the ploy that enhanced the first few FCBDs, hold ’em the day after a superhero blockbuster movie debuts. ... Keith Knight, who keeps busy with two weekly comics, The K Chronicles and (th)ink, will add a daily comic strip, the autobiographical Knight Life, starting in May, distributed by United Feature Syndicate. Says blogger Lore Sjoberg, announcing the advent: “I just hope the strip gets published online. I don’t pick up many newspapers these days.” Well, Lore, you’re missing a lot of good comic strips then. ... At EW.com recently, an assortment of comic book creators talked about the comic book that persuaded them to pursue their vocation. For Brian Michael Bendis, it was an edition of Fantastic Four No. 1 that came with a recording on vinyl; for Allison Bechdel, “probably not my first comic book,” The Adventures of Asterix, in which she could not read the French speech balloons but “the drawings were so rich and complicated” making the experience “peculiar and tantalizing”; for Jim Lee, an issue of Tarzan from the drawingboard of Joe Kubert; for Jessica Abel, the hardback collection of the Marston-Peters Wonder Woman published by Ms. Magazine; for Chris Ware, an early collection of Peanuts. Ten more at EW.com. ... And a week after winning the Pulitzer, Michael Ramirez won the editorial cartooning category of the Sigma Delta Chi Professional Journalism Society awards. ... In the wake of the presume success of its adaptation of Stephen King’s Dark Tower, Marvel Comics will soon begin the same sort of exercise with the novels of Orson Scott Card’s popular Ender series, saith PW Comics Week’s Laura Hutton. Another scrap of information falling during the NYCC. Peter O’Donnell, creator of Romeo Brown and Modesty Blaise, among others, had only one regret as he approached his 88th birthday on April 11. According to the Press Gazette in England, he’s sorry that he doesn’t know what became of the young girl refugee who supplied him with the “history” of Modesty Blaise before the character became an international criminal and then an unofficial agent for Britain’s secret service. The girl’s role in the creation process is given in our history of the strip, filed here in Harv’s Hindsight, in case you’d like to refresh your memory. O’Donnell recalls that it was in 1962 that he received a phone call from the strip editor of Express Newspapers, Bill Aitken, “who wanted me to write a strip. I asked what sort of strip, and he said: ‘I want the strip you want to write.’” O’Donnell had been mulling over a heroine who could do what James Bond and all the other male heroes did, but he needed some sort of “background” for the character who became Modesty Blaise. That’s when he went back to 1942 and that young refugee he saw, at a distance, while serving in what was then Persia (now Iran) with a mobile-radio detachment near the Caucasus Mountains. “The strip,” O’Donnell said, “was an immediate success and, to my great delight, was syndicated to 42 countries. It also led to a series of 13 novels that I greatly enjoyed writing, and a movie that I didn’t enjoy at all. The film was a well-deserved failure. I don’t really want to see somebody else’s concept of Modesty Blaise and Willie Garvin put on the screen. They’ve been my friends for more than 45 years now, and I like them the way they are.” It’s a sentiment that Alan Moore would no doubt applaud. “Moore,” writes Trevor Owens in the Comics Corner of Fullerton College’s Hornet (fchornet.com), “has been the victim (and the perpetrator, in part) of some travesties in intellectual property film adaptation. From Hell, perhaps the greatest graphic novel of all time [created in collaboration with Eddie Campbell], was castrated in a film adaptation that pleased audiences that did not know better.” Moore knew better. He had created the source material. And he was grievously disappointed and angry. At the time, however, he simply announced that he’d have nothing to do with film adaptations of his work: he’d just take the money. But when his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen was turned into a shadow of its former self by filmmakers, Moore vowed never again to permit another film adaptation of his work if he could possibly prevent it. If he didn’t own the work and couldn’t prevent its adaptation, then he wouldn’t allow the use of his name. “Moore created comics that shocked readers and emotionally moved them,” said Owens; “he has written a screenplay and published a novel. If his ideas suited other mediums, he would have not made them for comics.” Exactly. And now there is a flurry of anguished excitement about the forthcoming film version of Moore’s The Watchmen, which, alas, he doesn’t own and cannot therefore embargo. “If the From Hell graphic novel is well-regarded,” continued Owens, “Watchmen is worshipped. Moore and [artist collaborator] Dave Gibbons’ masterpiece should remain only as a comic; it was not intended to be a film and will not work when chopped and ground up to fit in a couple of hours on the silver screen.” True. “The only ray of hope for fans of the graphic novel Watchmen,” Owens concludes, “is that this is possibly the last Moore comic to be brutalized by cinema—there aren’t many left” that someone other than Moore owns. On April 15, a detachment of Egyptian police raided the Cairo-based Malameh publishing house and seized copies of a graphic novel entitled Metro, claiming it was “harmful to public manners” because of its use of colloquial language. Metro is the first graphic novel to be published in Egypt, and it refers to events of a political and social nature, reported the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information in Cairo, which condemned the police entering the publishing house without an official order as well as the confiscation of the book, which was termed a “severe violation of freedom of expression.” Al Sharkawi, the director of Malameh publishing house, is currently under arrest in connection with a strike held April 6. He was previously detained in 2006 and tortured while in detention. Even though the general prosecution recorded the abuse, the officers involved were never punished. The animation industry in China is booming. Last year, Chinese animation studios produced 186 animations with a total broadcasting time of 101,900 minutes (roughly 169 hours or three years of a weekly hour-long program). In China, said Ai Fang and Wang Xia on the China Economic Net, 34 tv channels and 4 animation channels, broadcasting about 8,000 minutes a day, are “a major platform, promoting the healthy development of the domestic animation industry.” With increased production for that platform, the quality of the product has steadily improved. In 2007, viewership of China Central Television’s channel for children ranked fifth among CCTV’s 16 channels. In the U.S., they say, the annual output of animation and derivative products amounted last year to $5 billion; in Japan, $9 billion. The global output value of the Chinese animation industry and derivative products related to video games and the like amounted to over $500 billion for a comparative period. Stand back: we don’t know how big this thing is gonna get. Fred Van Lente, who writes the intriguing Comic Book Comics (which we reviewed last time, Op. 221) for his partner Ryan Dunlavey to design and draw, says they time their publication dates to coincide with convention appearances, so the second issue will come out in July for the Sandy Eggo Con. The third issue, probably in October. He thinks they might go to six issues. As for content, here’s what he told Andy Oliver at brokenfrontier.com: “Well,

in No. 2 we get the explosion of the Golden Age, how World War Two

affected the comics (and vice-versa), the true confessions of romance

comics, and the rise of E.C. Comics. In No. 3, it's the Wertham purge and the Comics Code, the beginnings of comics fandom and the

birth of the Silver Age, and then we decide, once and for all, who

was the more important creator in the Marvel Universe—Stan

Lee or Jack Kirby.

This is sure to be our most controversial issue yet! In No. 4, we've

got Pop Art, the Adam West Batman tv show (two very related things), R. Crumb and the undergrounds, and the magazine comics of the 1970s—Warren,

Heavy Metal and the like.” Van Lente says he did a lot of

research for a biography of Kirby that he ultimately didn’t

write, and that’s why Kirby is the constant thread through the

first issue of the series. He and Dunlavey had decided before

finishing their first joint effort, Action

Philosophers, a series of biographical

comics, that they’d do a similar series on comics. “We

saw the ground coming up at us pretty soon on Action

Philosophers,” he said, “—we

knew we would run out of philosophers about half-way through the

series, and we wanted to keep this nonfiction comedy gravy train

rollin’, you know? The history of comics is still in the same

basic ballpark as philosophy—the humanities—but different

enough for us to stretch different muscles.” Action

Philosophers is collected in three volumes,

all available online at EvilTwinComics.com. *****

Michael Sangiacomo, a reporter at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, is, he says, “Cleveland’s unofficial comic-book ambassador” and always gets picked to squire interested visitors over to the slightly “tattered” Glenville neighborhood and the Kimberly Avenue house where Jerry Siegel was living in 1933 when he created Superman with his fellow teenager, artist pal Joe Shuster, who lived “a short distance away on Amor Street.” Shuster’s house, apparently, has been lost to the ravages of time, but Siegel’s house—the actual place where he dreamed up the Man of Steel—is still there, and its owner, Hattie Gray, revels somewhat in the place’s history: the house is “proudly painted Superman red, yellow, and blue,” Sangiacomo observes. Last fall, Sangiacomo took cartoonist Tom Batiuk out to the Siegel House, and they found Hattie Gray home, and she graciously let them in so Batiuk could see the third-floor workroom where Superman first saw the light of day. Batiuk took photos of the house because he has planned a sequence in Funky Winkerbean about a comic writer who gets stuck while writing Superman. A friend suggests that the writer visit The Birthplace, and he does. The sequence will run this summer, starting (it sez here) on Monday, August 11. The Denver Post reports

that Bob Dylan received

an “honorary Pultizer” for his “profound impact on

popular At the weeklong thinktank Conference on World Affairs held at the University of Colorado’s Boulder campus in early April, one of the notable thinkers who appeared to make a presentation was Tim Long, a writer for “The Simpsons,” who showed clips that were, by turns, “hilarious, bitter, and off-color,” reported Jerd Smith in the Rocky Mountain News. Fox Network, which airs the tv show, employs a phalanx of censors to “figure out what will get us into trouble and what will not,” Long said. Noting that people can now air their outrages online with the Federal Communications Commission, Long said one of his favorite complaints came from a viewer who found it “entirely inappropriate for the preschool audience that would be watching the show” the broadcast of a commercial about a homosexual encounter Bart had with a space alien. Said Long: “Would a heterosexual encounter have been okay?” The censors also objected to the mention of a sexual act that was performed 1,000 times, saying the number 1,000 was inappropriate. “When the writers suggested using 1 million instead, the censors signed off on the script.” It must be working for them: first airing December 7, 1989, “The Simpsons” is tv’s longest running show at 420 episodes. With a new series of books for children, TOON Books, Francoise Mouly, co-founder, with husband Art Spiegelman, of RAW magazine and, since 1993, art editor for The New Yorker, hopes to get kids interested in reading. “My husband and I both developed our love of literature through comics,” she said, adding that Art says “comics are a gateway drug to literacy.” The series launches with three titles: Benny and Penny in Just Pretend by Geoffrey Hayes, Silly Lilly and the Four Seasons by Agnes Rosenstiehl, and Otto’s Orange Day by editoonist Frank Cammuso and one-time undergrounder Jay Lynch. Interviewed in Horn Book (hbook.com), Mouly observes a fine irony: “As the medium grew up, kids got left behind. So that’s precisely why, after saying for decades, ‘Comics, they are not just for kids anymore,’ Art and I are now saying, ‘Comics, they are not just for adults anymore.’” ... Apparently not. At NYCC during a Kids’ Comics Publishers roundtable, reported in PW Comics Week, Diamond’s Janna Morishima said: “Over the past few decades, kids’ comics have become the most underground of underground comics. Only in the past few years has that started to change.” She cited First Second’s children’s line, Scholastic’s Graphix line, “and the growing trend of trade houses releasing graphic novels for children and traditional comics publishers developing titles for children as evidence that the market is growing.”

*****

Superhero Summer. A superhero summer looms on the silver screen horizon. Five blockbusters are poised to amaze and amuse, only one, “Hancock,” not a fugitive from four-color fantasies: “The Incredible Hulk,” “Iron Man,” “Hellboy II: The Golden Army,” “The Dark Knight,” and “Hancock.” Entertainment Weekly (April 25 / May 2) predicts that all but “Hellboy” will be in the top ten grossing movies of the summer, with the new Indiana Jones effort in first place. Comic book inspired superhero flicks have numbered in the top five money-makers in each of the previous four summers, 2006 including both “X-Men: The Last Stand” and “Superman Returns.” Marvel’s newly formed production company, with two movies in the wings, has the most to lose—or to gain. Its first franchise effort is “Iron Man,” which stars the unlikely Robert Downey, Jr., whose high-profile substance abuse history apparently helped him get the assignment: Tony Stark [aka Iron Man] has had a vew substance abuse problems himself. But Downey, by all accounts, did just fine. Director Jon Favreau started shooting last winter without a firm script, and Downey, with a reputation for “in-the-moment inventiveness,” did some of the re-writing, determined not to let F/X overwhelm story (character and drama). Downey was intrigued by the Iron Man concept: “Stark is something of a weirdo compared to other superheroes. Whereas most of them are dealing with some extraordinary transformation, he’s very self-indulgent, a womanizer, and politically unsound by most people’s standards. And yet, my understand is that Iron Man got more [female] fan mail back in the day than any other Marvel character.” Downey was delighted to get the part, saying: “All the guys I’ve grown up with in this business, all my peers, they’ve all gotten their superhero ya-yas out, except me. Until now. I feel like I’m on Planet Iron Man, and it’s the greatest.” What with the flop of 2003's “Hulk,” another movie about the character might seem foolhardy, but because the Hulk is almost as popular as Spider-Man, the moguls at Marvel’s new movie company decided a “do-over was worth the risk.” But this one isn’t another origin story: it begins with Bruce Banner in Brazil trying to find a cure for his monster addiction. “The new ‘Hulk’ film is said to remain truer not only to the comic book but also to the old Lou Ferrigno tv show.” Some publicity has alleged a “feud” between the movie makers and the Marvel production company. The movie’s director, Louis Leterrier and its star, Edward Norton, supposedly wanted a longer, “more meditative cut of the film,” but Marvel wanted an action-packed commercial film, running less that two hours. Marvel won, but, contrary to rumor, Norton and Leterrier are not sulking. In a statement at EW.com, Norton, who was said to be boycotting the movie, says that typically movies are collaborative efforts in which a variety of ideas are aired, some adopted, some not—“the heart of the filmmaking” process. “Our healthy process, which is and should be a private matter, was misrepresented publicly as a ‘dispute,’ seized on by people looking for a good story, and has been distorted to such a degree that it risks distracting from the film itself, which Marvel, Universal, and I refuse to let happen.” He “concedes that Marvel’s cut, though not what he wanted, is more commercial than his. ‘He’s very Zen about it,’ says a source.” The Bat-flick, starring, again, Christian Bale with Michael Caine returning as Alfred, features the late Heath Ledger as the Joker, a role Jack Nicholson made famous. Ledger’s work is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the production, saith EW, quoting, in addition, another of the film’s actors, Aaron Eckhart: “I knew from the first day on the set that Heath was going to totally redefine the Joker. He just really got into it and took the character to the limit.” Said EW: “It’s impossible to know how Ledger’s performance in ‘The Dark Knight’ might have been perceived had the actor lived to see the film’s opening.” Added Eckhart: “That could be a good thing. You know, maybe it’ll just make people think about Heath’s talent.” “Hellboy II,” says its director Guillermo del Toro, is “more idiosyncratic than the first one” and is “steeped in ‘folklore, myth and fantasy’ ... but also makes time for some domestic comedy between Hellboy (returning Ron Perlman) and his pyrokinetic girlfriend Liz (Selma Blair),” who are now sharing an apartment. Based upon an original story by the character’s creator, Mike Mignola, the movie glimpses a world in which “fantasy is literally dying,” which, says del Toro, gives the production “a beautifully melancholic sense of loss ... —that, and kick-ass action.” “Hancock,” the only non-comic book production, stars Will Smith as a “flawed, widely reviled alcoholic” who is, otherwise, an invincible do-gooder with superpowers who is seeking “to rehabilitate his public image with the help of a marketing expert.” Smith was attracted to the project because of its “slightly quirky, off-center approach,” mixing action comedy and serious drama. Said director Peter Berg: “If ‘Hancock’ works, those big tone shifts will separate us from films of the past.” The photo in EW shows Smith lifting up a car, evoking memories of another superhero on the cover of an antique comic book.

*****

The San Francisco Chronicle gave Darrin Bell’s Candorville strip a trial run in the Doonesbury slot while Garry Trudeau is on sabbatical, and then the paper asked its readers what they thought. “More than 200 responded,” Editor & Publisher reported—60 percent of whom liked the new strip; 40 percent didn’t. In an accompanying piece, Executive Datebook Editor David Wiegand wrote: "A few readers said or implied that one of the reasons they like [Candorville] is because its lead characters are African-American. That was one of the reasons we were first attracted to it, to be sure. We want to find strips that reflect the diversity of the Bay Area, but that's easier said than done. For one thing, there are a lot of strips of every kind out there and you’d be surprised how few of them are very good, or funny, or even well-drawn. Several times a year, we're visited by very nice people representing the comics syndicates and they all tell us how certain they are that some new strip will do well in our market. And several times a year, I look at them and wonder if they have any idea of what our market is...." My vast biography of Milton Caniff has just been nominated for an Eisner in the Comics-related Books category. You can find all the Eisner nominees for 2008 at the Comic-Con International website (www.comic-con.org). I’m thrilled to be among the nominees but have very little expectation of winning. Gary Groth, whose Fantagraphics published the book, told me in 2006 when he finished reading the typescript: “This is the best thing you’ve ever written.” I have a high opinion of Groth’s abilities as an editor, so I was bowled sideways. And then I paused in the midst of my happy dance to think about it. The typescript he read was an everso slightly revised and massively reduced version of what I’d finished writing in 1989. So “the best thing” I’d ever written was written nearly 20 years ago. Since then, apparently, my skill has been steadily deteriorating—even as I contributed regularly, virtually every issue, to The Comics Journal, also published by Groth. This steady downhill trend has culminated, it seems, in an Eisner nomination at the bottom of the hill. We missed this one: on or about January 20, Ginger Meggs, Australia’s famed comic strip about the antics of a larrikin (unconventional) red-headed and somewhat mischievous kid, started appearing over the signature of a young cartoonist in Perth, Jason Chatfield, who is but the fifth to produce the strip, which, launched in November 1921 as Us Fellers by Jimmy Bancks, is arguably the third longest-running comic strip in the world (after The Katzenjammer Kids and Gasoline Alley). Bancks was followed after his death in 1952 by Ron Vivian, who kept it up until he died in 1973. The strip was then inherited by Lloyd Piper, who was the first of Bancks’ successors permitted to sign his name to the feature. When Piper died in 1984, he was succeeded by James Kemsley, who died December 3, 2007. Kemsley revitalized the sagging feature: he added daily releases to the Sunday only Ginger Meggs, and through sheer determination and persistence, he increased the Down Under icon’s circulation from a handful of Australian papers to international syndication in over 120 papers in 32 countries. Still, income is modest; Chatfield plans to continue doing editorial cartoons for the Perth Voice and the Loconut.com website as well as the strip. He recalled that Kemsley told him “the whole newspaper comic strip industry is at the mercy of American syndicates”; Ginger Meggs is distributed in the U.S. by Atlantic Syndicate/Universal Press. Five days before he succumbed to motor neuron disease, Kemsley asked Chatfield to continue the strip, having checked, first, with Sheena and Michael Latimer, Bancks’ daughter and son-in-law, keepers of the Ginger Meggs flame. “This is an amazing honor,” said Chatfield recently, when the strip was picked up by another Australian newspaper. “I’ve worked really hard to honor Kemsley’s memory and at the same time put my own slant on the strip,” continued Chatfield, who was born the year Kemsley took on Ginger. “I’ll certainly be modernizing it. Ginger Meggs will reflect the changes in Australian culture, language and concepts to keep it relevant to readers.” He intends, he said, to keep doing the strip for the rest of his life—“and to keep it going well past its 100th year.” Here is a sample of Kemsley’s Sunday color work: he deployed the strip’s layout differently from week-to-week. Also on display, two Kemsley dailies at the top, and at the bottom, two by Chatfield, including his farewell to “Kems.” Although I doubt you can read it, Chatfield’s second daily includes a “saying” like all of Kemsley’s do—a scrap of wisdom culled from some manual of popular aphorisms, no doubt. The two in Kemsley’s strips are: “Life is only as long as you live it”(which is lettered upside down) and, “A little knowledge gets a lot of people elected.” Sometimes the saying is related to the doings in the strip; mostly, not. The original of these was not an aphorism at all: Kems was behind on deadlines and knew he’d miss a cricket match his team was playing the next day, so he told his teammates he couldn’t get there by lettering a message to them into a strip that would be published the next day. In those days, the strip was probably published in only a few papers, and in Kemsley’s home base paper, it was doubtless printed the day after the cartoonist drew it. In any event, readers were intrigued by the message, so Kems started doing a new one every day—just an aphorism or axiom, though, no longer an urgent notice to friends or colleagues.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Irks & Crotchets “It is telling that in our uniquely American taxonomy, Barack Obama is almost always described as a black man with a white mother and never as a white man with a black father.”—Ellis Cose, Newsweek, March 31, 2008 “Isn’t the Surge getting a little old to be called ‘the Surge’? It’s beginning to sound like one of those four-hour erections that men should call their doctors about. It needs a new name, like ‘The Long Goodbye.’”—Donald Kaul, syndicated columnist and two-time Pulitzer Prize loser “I have no doubt we are in the midst of a global warming,” saith Darth Cheney, speaking at the annual White House Radio and Television Correspondents dinner, “—or, as I prefer to call it, spring.”

COMIC STRIP WATCH To commemorate Earth Day, April 22, King Features asked its cartoonists to come up with eco-awareness strips. Participants included stalwarts like Beetle Bailey, Blondie, Dennis the Menace, Hagar the Horrible, The Lockhorns, and Zits, plus a clutch of the newer strips like Arctic Circle, Retail and The Pajama Diaries. "While the funny pages are about making people laugh, they have also historically been a forum for social expression," Brendan Burford, the comics editor for King Features, said in a statement. "We are proud so many of our cartoonists feel as passionately about the environment as we do." Probably

United Feature didn’t formally second the motion, but Michael

Fry and T (no

punctuation) Lewis at Over

the Hedge devoted the entire week before

Earth Day to an, er, “earthy” topic. Flatulence. Not your

usual comic strip topic, and a little near the edge even in these

increasingly liberated times, but definitely in the “save the

earth” mode. Here’s the whole week. Back

to Earth Day. I agree with Burford that commemorating Earth Day is a

good thing, but I also think Jim Toomey went a little overboard by converting Sherman’s

Lagoon on Sunday, April 20, to a form letter

that readers could fill out and send off to the Director of the

National Marine Fisheries Service to support saving some sharks. Below the Shark Campaign is one of those Occasional Oddities that rarely infect the comics page: two strips with vaguely similar jokes or pictures. In this case, both strips deploy figures so large that only their lower extremities can be depicted; and both strips want to “talk to you” about something. Further enhancing the deju vu too effect, these two strips appeared in the local paper exactly as they appear here, one atop the other, one almost a visual echo of the other. At the bottom of this visual aid is another Over the Hedge strip that ran on the day of the Pennsylvania primary. Written on April 11, ten days before the election, Fry and Lewis predicted that Hillary will win by 9 percent; she won by 10, which proves that, all the pundit excitement to the contrary notwithstanding, the outcome in Pennsylvania was never much in doubt: Hillary has polled ahead of Obama in that state for as long as polls have been conducted. But the “gracious act” of political sacrifice is a nice quirky touch. And Hammy the squirrel always sets me free.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to these shores was heralded by Newsweek (April 21) with an article that included, at the end of the first paragraph, the following: “A few years back, a veteran Vatican bureaucrat remarked that ‘God has been very kind to us: we haven’t had a wicked pope in 500 years.’” I suppose that the magazine does not mean to imply by entitling the article “How Benedict XVI Will Make History” that Benedict is breaking that 500-year record, but theirs is an unfortunate juxtaposition of notions. One of the less distinguished of Benedict’s predecessors—of which there are legions—is Stephen VI, who, in 897 during his brief 15-month papacy, accused former Pope Formosus of perjury and violation of church canon. The magazine Mental Floss (May-June) takes the tale from there: “The problem was that Pope Formosus had died nine months earlier. Stephen worked around this little detail by exhuming the dead pope’s body, dressing it in full papal regalia, and putting it on trial. He then proceeded to serve as chief prosecutor as he angrily cross-examined the corpse. The spectacle was about as ludicrous as you’d imagine. In fact, Pope Stephen appeared so thoroughly insane that a group of concerned citizens launched a successful assassination plot against him. The next year, one of Pope Stephen’s successors reversed Formosus’ conviction, ordering his body reburied with full honors.” Mental Floss, by the way, is a bi-monthly publication that specializes in obscure facts, factoids, and the like. The perfect journalistic diet, in other words. I wouldn’t be without it. Words go in and out of fashion. I’ve encountered the word canoodle three times in the last six months; maybe four or five altogether in the last year. But I can’t remember seeing it much before that—for years. And yet, I remember it from years ago. It refers to “cuddling, or caressing in a sexual way.” If we are to judge from the seeming increase in the frequency of usage, there’s apparently more of it going on these days than before. Canoodling must be on the rise.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being too mysterious or cryptic. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. Alas,

the last two titles from the habitually brilliant Warren

Ellis leave me shivering on the curbstone,

none the wiser. Unamused and baffled. A bad beginning in any

estimation. The eponymous Anna Mercury, some sort of agent in a

tight-fitting leather suit, has a massive tangle of red hair about

the size of her body. She spends the opening pages of the first issue

of her title swinging like Bat-Spider-Man through the concrete

canyons of a city, landing, feet first through an upper-story window,

in a meeting of several unsavory types that she vanquishes with a

flourish of broken glass, shattered jaw bones, and a spray or two of

blood. This ends the episode of this issue—the only part with a

beginning and an ending—but it leaves more questions unanswered

than is good for it and is therefore not an emotionally satisfying

encounter. There’s no sense of closure, however momentary,

which a first issue episode must yield. One of these unsavory types

she knows, a simple-minded young galoot, and she questions him about

the test-firing of a “gun,” rubbing up against him with

her fist clutching his equipment. He keeps whining about his ha But not as much mysteriousness as we find in Doktor Sleepless: Bastard of Tomorrow, which is even more baffling than Anna Mercury—and the issue before me is the third in the title; by now, you’d expect some scraps of knowledge to have surfaced. Not so. I don’t know who Doktor Sleepless is or why. The book wanders back and forth among three or four or five locales. In one, a man in a prison cell tells a story to some other blokes, who may, or may not, also be inmates. More likely, they’re the storyteller’s interrogaters. Maybe he’s John Reinhart, the only name to crop up in the book, and maybe John Reinhart is Doktor Sleepless. The story the man in the cell tells is about a Tibetan monk and something called a tulpa and the capability of a mind to create matter that lives a separate existence. We then see a masked man in a raincoat on a ledge overlooking the city. Next, we’re in a happily-named shop, Catastrophe Books, where two women, the shopkeepers, talk a little about Doktor Sleepless and a box of books he’s sent, which one of the two women then sells to a mob of buyers. Then we’re outside in the rain with another nameless person, a man, who mutters to himself that “the me you used to kiss thrashes like a cat in a sack, somewhere in the back of my head, trying to get its claws through thick lithium.” Nice turn of phrase, but not very instructive. Then we’re in a huge house on a hill in which a petulant young girl accuses her mother of killing her father. There are a few more pages, but I learn nothing from them that helps. Too bad. I usually like whatever Ellis does. But not this time: too much mysteriousness, like I said. The

artwork in both of these titles, by Facundo

Percio and Ivan

Rodriguez respectively, is not only competent

but expert.

***** THE CLASSICS, ILLUSTRATED AGAIN I don’t know who Malcolm Jones is or what credentials he presented to Newsweek to get the gig reviewing “newly published Classics Illustrated” in the March 31 issue, but whatever Jones’ qualifications may be, he demonstrates no particular understanding of the comics medium. It’s a healthy dose of plug for comics, a three-page article, one page of it devoted to a full-page illustration from Marvel’s The Man in the Iron Mask, which Jones doesn’t refer to at all, but apart from issuing a nostalgic wake-up call, the piece does nothing that will enable the magazine’s readers to comprehend and therefore appreciate the unique artistry of comics. The “Classics Illustrated” Jones discusses is the series emanating from Papercutz, the NBM youth imprint edited by Jim Salicrup. As if to spite the full-page illustration, Jones ignores the recent Marvel foray into these elysian fields of yesterday’s literature; I won’t, but more of that anon. While Jones manages to let slip an occasional thought worth noting, his article is mostly a self-indulgent paean to “the touchstones of his childhood”—namely, the original Classics Illustrated. These he extolls for their having exposed him to “stories” he was otherwise not going to be reading in their original, un-illustrated states as prose novels. In Classics Illustrated, Jones says, “I first discovered just how good stories could be.” “Stories,” mark you, not “comics” or “artwork.” For Jones, Classics Illustrated, then and now, is simply “stories.” He’s glad to see them returning to American life because they’ll acquaint new generations with “stories” and “how good” they can be. Stories. A story is a sequence of events (first this, and then that and then and then and then); when the sequence is informed by a plot (which indicates why something happened), we approach literary merit. But for Jones, “story” is the whole nutshell. Because of his deluded idea about what literature is, he reports that, having read Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows and Michel Plessix’s graphic novel version of it (also Papercutz)—“both for the first time”—he can’t say which one is better. “Their charms are different,” he admits, “but each man has created a wonderful world, one out of words and the other in images.” At least Jones acknowledges that the two versions of the story are achieved in different ways. “Plessix,” Jones writes, “reminded me that Classics Illustrated was the way I got in” (“into” stories, presumably). He can talk about how much he likes Plessix’s pictures but he can’t find a way to praise Grahame’s languid prose. No question, Plessix’s version is brilliantly done, and I’ll have more to say about it when we visit The Wind in the Willows and its illustrators in Harv’s Hindsight in a few weeks. My point is not that Jones is wrong about Plessix. Or about Grahame. The point is that he is posing as a critic of a visual literature (funnybooks) but he can’t articulate how Plessix is different than Grahame except to say the former draws his world, the latter writes his. All of which is true. But if Jones knew his stuff, he could tell us how the two achieve effects based entirely upon their differing media. Since Jones dotes solely on “story” in his examination of literature, he clearly can’t tell the difference between the two Willows because both tell the same story. And

I could let it all drop without a murmur if he didn’t pursue

his misbegotten notion by criticizing Rick

Geary’s graphic novel interpretation of

Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, another Papercutz production (56 6.5x9-inch pages in color;

hardcover, $9.95). Jones confesses that he admires Geary’s

ability to condense Dickens’ “hideously complicated

story” into a work that can be read “easily and swiftly”

despite the “visually crowded” pages, but then he

displays his towering ignorance of Dickens when he says: “Geary

is probably not the best choice to illustrate Dickens.

Temperamentally, he’s simply not dark enough. His version of Great Expectations misses

most of the danger and all of the gloom.” Danger? Gloom? Jones

is undoubtedly remembering David Lean’s haunting 1946 film of

“Great Expectations,” not Dickens’ novel. Dickens

can be gloomy, and menace lingers throughout Great

Expectations, as it does through Bleak

House and Our Mutual

Friend and, even, A

Christmas Carol, but Dickens also regales us

thoughout with some of the funniest characters in

literature—exaggerated, caricatured vignettes of quirked

humanity. Exactly the sort of pictures Geary makes. Geary is clearly exactly the best choice to

illustrate Dickens. Well, enough in this vein. We should be grateful to Jones for giving the larger world a glimpse of the graphic novel versions of literary classics. In the two Papercutz books we’ve just looked at, the artwork is undeniably superior to the drawings in the Classics Illustrated comics that Jones so fondly remembers—a measure, no doubt, of the improved cultural and economic situation of comic books these days: publishers can afford better artists. And that sort of high class rendering prevails in Marvel’s adaptation of literary classics, which, so far, appear in serial format; probably Marvel will bundle the issues together to recycle as graphic novels and market them to junior high schools. I dipped lately into recent issues of The Iliad and The Picture of Dorian Gray, both adapted by Roy Thomas, who proves adept at varying his prose style to evoke his originals. The captions in The Iliad reek of antique Homeric locutions, and in Dorian Gray, we are reminded of Oscar Wilde’s graceful prose. As usual with Thomas, much of the narrative is advanced by the prose, pictures merely illustrating a verbal drone that hums through the books. The “drone” I have in mind, incidentally, is like that constant note sounded by one of the pipes in a clutch of bagpipes: it’s part of the music. And Thomas’ drone in these book is part of the storytelling. The motivating role given to verbal content here is probably unavoidable: condensing a long story into a comparatively few pages of comics requires the sort of shortcutting that can be done verbally but almost never with pictures bearing most of the freight. By the end of this issue, the third, of Dorian Gray, however, the narrative shifts from a glancing overview of the events of weeks, months and years to rehearsing a particular encounter between Gray and a friend, and there, Sebastian Fiumara’s delicately rendered Victorian visuals assume their share of the storytelling burden. In The Iliad, the narrative task is much more complex: Thomas must advance the story while deploying an array of leading characters, each with an unfamiliar Greek name. The pages are crammed with captions and speeches, around which Miguel Angel Sepulveda and his inker, Sandu Florea, weave expertly performed battle scenes and bloody encounters, all made even more complicated by the presence of gods and goddesses in ghostly outlines, hovering over their favorite warriors. By the end of this issue, No. 2 (of 8), the Olympians announce they are retiring from the field to let the mortals do battle as they can. Henceforth, Thomas’ task, and that of his collaborators, will surely be easier.

A LITTLE BUSHWACKING IS A GOOD THING No Surprise Not surprisingly, the Pope did better in confronting and assuaging those in his flock who have the most to complain of than has the Prez of the U.S. Benedick met on Thursday, April 17, with several middle-aged persons who as children had been sexually abused by priests in Boston. Face-to-face, and, briefly, one-on-one. GeeDubya has yet to do the equivalent—meet, face-to-face, one-on-one, with any of the mothers of slain American soldiers who now vociferously disagree with George W. (“Warlord”) Bush about the Iraq fiasco. The Pope has the courage of his convictions. The Prez of the U.S. is just a rich kid ex-Yale frat boy who found a post-graduate career in which to exercise the only skills he learned in college, those of a cheerleader. In the U.S., Catholics, victims of ferocious bigotry a century ago, now occupy five of the nine seats on the Supreme Court and make up more than a quarter of Congress—a signal change in cultural and political status, observed the New York Sun, quoted in The Week, which goes on to cite a Georgetown University study that found that a third of the country’s 64 million Catholics never attend Mass, a quarter attend church only a few times a year, and a majority never go to confession. USA Today notes that, thanks to Hispanic immigration, Catholics are “holding steady” at about a quarter of the nation’s population, but “native-born Catholics—especially those under 30—are fleeing the church by the millions.”

The Sacred and the Profane. On Saturday, April 19, the Pope conducted mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and CNN broadcast the whole thing, accompanying it with a voice-over running commentary by a couple of happy talk announcers who, at one time, took the occasion to discuss the Pope’s various pronouncements on sex abuse among the American clergy, laminating the sacred with the most scandalous profane. Typical American tv, in other words. Well?—given the Church’s history lately—why not?

EDITOONERY Afflicting the Comfortable and Comforting the Afflicted Editoonist Vaughn Larson, a National Guardsman in Madison, Wisconsin, for nearly 20 years, is in Guantanamo for his third tour of overseas duty. He served in Desert Storm in 1990; then in April 2006, while cartoonist and news editor for The Review, a thrice-weekly paper in Plymouth, Wisconsin, he was sent to Iraq for a year. While there, he filed stories and sent cartoons to The Review and two other papers that publish his work—The Wisconsin State Journal in Madison and The Freeman of Waukesha. “I can’t say I’m widely syndicated,” he joked at the time in an Editor & Publisher article; “I’m just minutely syndicated.” He’ll be in Gitmo until next March. Elsewhere: Some editoonists work with a cable news channel on the tv as they work; others play NPR or CNN on the radio. They do it to keep up-to-the-moment on the news of the day, seeking, as always, inspiration for the next cartoon. But broadcast news, whether audio-visual or just audio, is “headline news,” a digest of the day’s events as they transpire. And broadcast news often indulges in endless recycling of the Sensation of the Day or similar trivia about the celebrity of the moment. Anyone forming an opinion of the import of events from broadcast news necessarily gets only a bird’s-eye view of the tip of the iceberger, so to speak. Somewhat like arriving at an understanding of an elephant from an inspection of its tail. Or else the opinion is based upon events or personalities so unimportant as to be nearly meaningless in the Grand Scheme of Things. Given the source of their inspiration then, what kind of editorial cartoons can we expect from even the most talented cartoonists?

SCRAWLS ON THE BATHROOM WALLS Red

meat is not bad for you; fuzzy green meat is bad for you. Artificial intelligence is no match for natural stupidity. The latest survey shows that three out of four people make up 75% of the population

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution The journalistical rumor millrace has Katie Couric stepping down as anchor of “CBS Evening News,” perhaps in January after the Presidential Election. She’s failed to deliver the ratings that her 5-year $75 million contract prognosticated. She was supposed to “reinvent” the tv news program, but the network abandoned all the new Couric gimmicks when the initial ratings began to falter, resorting to the standard evening news broadcast format. It’s a solid news report, but still hangs third in the big three network ratings competition, and a week or so ago, it reached the lowest ebb of the broadcast’s history. Despite the rumors, CBS maintains it has no plans to make changes. Some pundits have speculated that the reason for Couric’s abysmal showing have less to do with her than with an American proclivity favoring male news anchors over female. It’s just a sexist thing. But James Poniewozik at Time.com contends that no one could have halted the relentless slippage in network news show ratings. The Week quotes him noting that only a small percentage of Americans—“most of them over 50—have the time or inclination to watch a half-hour tv newscast in the evening; those who do will ultimately die. No star or futuristic set or new format will fix that.” Newspaper circulation continues its steady decline. Editor & Publisher says that since 2004's semi-annual Audit Bureau of Circulation report, the top twenty metropolitan newspapers have collectively lost more than a million in circulation, an 8 percent drop. Some papers hope that by adding their website readers to the figures, they can recoup some of the over-all loss in the number of people buying the paper. We’ll see: the next ABC report is due at the end of April. Meanwhile, newspapers, desperate to increase profit for stock holders but unable to do so by raising advertising revenue because circulation is declining, are now seeking to enhance their bottom lines by reducing cost, which, these days, means firing staff or, increasingly, outsourcing some of their function. Print journalism has outsourced for decades: syndicated features and wire-service news reports have long been part of the daily mix. But now some big papers are having their ad production (design, layout, typography) done off-premises—specifically, in India. Data is e-mailed to one of several Indian companies specializing in ad production; the next day, return e-mail delivers the ads in camera-ready (so to speak) form. Jennifer Saba at E&P reports that newspapers are saving from 20% to 60% in production costs. “Back of the envelope calculation,” she writes, “shows that metro newspapers can realize a savings of about $500,000 a year. ... Chains like the Sun-Times Media Group [which plans to] outsource its ad production work for its 95 publications to Affinity Express [in India] expects to save $3 million annually.” Creators Syndicate has started identifying the political leanings of its pundit columnists, writes Dave Astor at E&P. Tagging a columnist C, L, LT, or U (Conservative, Liberal, Libertarian, or Unaffiliated) enables client paper editors who are casting about for a variety of views to quickly pick what they need to balance their op-ed pages. Some columnists, like liberal Connie Schultz and conservative Bill O’Reilly, don’t like to be pigeonholed. “I like to think I’m more nuanced,” said Schultz. O’Reilly, who makes no comment but who can scarcely be described as “nuanced,” no doubt wants to remain untagged so he can slip into a newspaper’s line-up like a stealth bomber, dropping hyperbola and innuendo as if reporting actual fact instead of opinionated vituperation.

BOOK MARQUEE The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics is, apparently, out, and if it’s anything like The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics that surfaced a few months ago, it will fall somewhat shy of including all the “best.” The War Comics included nothing from EC’s Frontline Combat or Two-Fisted Tales, for instance, arguably the best war story anthologies every published in comics. The War book spans a healthy swath of the 20th century though: stories from the 1960s (earliest, 1962) through 2005. The book was first published in Britain, so it logically includes British as well as American comics—and some samples from other countries, notably, “I Saw It!,” Neiji Nakazawa’s recounting of his own experience witnessing the atomic bomb falling on Hiroshima, which led, we are told, to “a much larger work, Barefoot Gen,” a classic Japanese graphic novel. Although nothing from EC is included, the work of some of its notable artists—John Severin and Joe Orlando—appears, as do a couple of latter-day stories from Will Eisner and a brace of unlikely creators, Greg Irons and Don Lomax. It may not include EC material, but maybe that’s a bonus: in the range of other material assembled here by David Kendall, we see many powerful pictures and telling narratives, and we learn thereby that EC Comics was not alone in portraying war as it is rather than as the glorious “romantic” mission some, like our own benighted Prez, GeeDubya, would have us believe it to be. Jen Sorensen, creator of the award-winning strip Slowpoke, which appears in the Village Voice and other newsweeklies, has released a new collection of the feature, Slowpoke: One Nation, Oh My God! with 150 of the cartoons and an introduction by Ruben Bolling of Tom the Dancing Bug notoriety. Says Sorenson in a news release from aan.org: “This is not just another quirky cartoon book. It is packed with commentary for every strip and chock full of devastatingly sophisticated and accurate political analysis. It also answers all your questions about tube socks and teledildonics.” Teledildonics?

*****

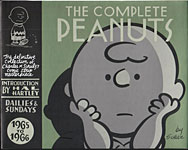

MORE PEANUTS YET The latest in the Fantagraphics Peanuts reprint extravaganza is out, The Complete Peanuts: 1967-1969: The Definitive Collection of Charles M. Schulz’s Comic Strip Masterpiece (340 6x8-inch pages, b/w; hardcover, $28.95), and it, like the previous eight volumes, is a superb example of the book designer’s craft, here, Seth’s. Nothing in the design draws particular attention to itself and therefore away from the book’s chief function, which is to present the comic strip to the best advantage—in this case, three daily strips to each page, uncluttered and therefore unblemished by any of those self-conscious designer-ish gimmicks like drawings screened to gray tone lines thereby destroying the art that you bought the book to look at or blown up so that the lines are raggedy and unattractive—nothing, in other words, Kiddish at all. Only in the book cover, jacket, and front- and back-matter is Seth’s subtle touch on display, its austerity matching that of the cartoonist’s simple but expressive visuals. Each

cover of the series has carried a bold-line close-up of one of the Peanuts cast, accented

with gray tone and bathed in a subdued color, a different one for

each book. In taking the book design assignment, Seth (aka Gregory Gallant), a cartoonist himself (graphic novels like Clyde Fans: Book One and Wimbledon Green and It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken), wanted “a chance to do something beautiful for Sparky [as Schulz preferred to be called]. It is a daunting task in that sense,” he continued: “You have the responsibility of trying to honor the great man with your own paltry skills. You don’t want to do anything that will hurt his work. The only thing that makes it easier is that there have been many many horrible editions of Peanuts, and his work still goes on unharmed. At the very least, I can’t hurt Peanuts.” Schulz’s work had a “profound influence” on Seth, he said, adding that “the only other cartoonist of equal value as just such an example would be R. Crumb. Though, seeming, both from different ends of the cartooning spectrum, they both have a lot in common. They both, uncompromisingly, did exactly what they wanted to do. They had a vision and they followed it through unflinchingly. Also, both of them managed to infuse their work with the power of their inner life—making a medium that is usually vapid and commercial and using it for very personal expression. This sort of thing is a great inspiration to anyone who believes that cartooning can be a meaningful pursuit.” In the volume at hand, John Waters’ introduction takes appropriate notice of Schulz’s skill as a cartoonist, referring us, as too few introductions to comic strip reprint books do, to specific examples in the ensuing pages. This book sees the arrival of Franklin, the African American kid, and baseball star Jose Peterson, introduced for his brief appearance by Peppermint Patty, who bowed onto the Peanuts stage August 22, 1966, as revealed in the previous volume, which achieves even greater historic status for Snoopy’s donning goggles and helmet and climbing atop his doghouse as the Famous World War I Flying Ace to engage in endless battle with the storied Red Baron, Sunday, October 10, 1965. In the 1967-1969 volume, we also witness that rare phenomenon in Peanuts, an adult presence, an off-camera voice—the ticket seller at the movie theater. This may be the last time such an untoward thing happened in the strip. Isolated episodes like these are identified for us by one of the series most helpful features, an Index at the back of the book that tells us which pages to look at to see Snoopy as the World War I Flying Ace or as a vulture. I suspect the indexer of a mischievous cast of mind, though: in the 1967-1969 volume, I can’t find Zorba the Greek anywhere on page 104; he may exist solely to give the letter Z a referent. But we can easily tolerate and even overlook such playfulness in order to find who first wears a fake moustache. (It’s Snoopy, effecting a disguise as the World War I Flying Ace, shot down behind enemy lines.)

*****

ANOTHER HISTORY OF COMICS CENSORSHIP AND RUIN Mort Drucker, Mad’s caricaturist supreme, has provided us all with an excuse to buy the May issue

of Vanity Fair, the

one with Madonna’s naked thighs on the cover. Inside, we can

see more pictures of Madonna’s thighs and of her visage, which,

nowadays, bereft of its adolescent babyfat and framed by long,

luxuriously curled locks, is genuinely beautiful in a classical

sense. But Drucker is the gem we found a few pages before happening,

altogether unawares, upon Madonna. On page 186, he celebrates what David Hajdu calls Mad’s 60th anniversary by caricaturing a dozen or so of the magazine’s