|

|||

|

Opus 197:

Opus 197 (December 11, 2006). Our main feature this time is a

long review and analysis of Alison

Bechdel’s graphic novel, Fun Home—“uncontestably,”

saith the London Times, “the graphic

book of the year.” Neel Mukherjee continues: “An unflinching, multilayered

memoir of growing up in small-town Pennsylvania. ... A complex love-letter not

only to her father but also to books and reading, Fun Home is luminescent with wit, lyrical prose, intelligence,

honesty and emotional truth.” On this side of the Atlantic, the New York Times lists Bechdel’s book

among its list of “100 notable books of the year.” We also commit an extensive

review of DC’s Batman and the Spirit, which marks Darwyn Cooke’s debut drawing the iconic Spirit, and examine the

annual “cartoon issue” of The New Yorker, which, again this year, falls short of its inherent obligations. Here’s

what’s here, in order, by department:

NOUS R US

Dave

Cockrum Dies; a link to obit

Steve Sack Named Berryman Cartooner of

the Year

Don

Trachte’s Rockwell Sets a Record

Manga

Again

Marvel’s

Movie Moves

The

Secret Origins of Borat

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

Batman

and the Spirit

Vol.

19 of the Spirit Archive

Norton’s

Eisner

COMIC STRIP WATCH

Pearls

Before Swine

Opus Takes on Disney

BOOK

MARQUEE

Cancer

Vixen

REPRINT REVIEWS

Sherman’s

Lagoon

Tina’s

Groove

GRAFICITY

Fun

Home

NOTES

ON THANKSGIVING

Cartoon

Issues

‘Bye

Fats, A Personal Note on the Passing of Another CBS Stalwart, Christopher Glenn

And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by

clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just

this lengthy installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without

further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives Us Fits

Comics

continue to invade the hallowed halls of museums. Rancid Raves spy Bill Crouch

reports that 300 cartoons from 50 countries will be displayed in three New York

City venues under the heading “Drawing It Out: First International HIV/AIDS

Cartoon Exhibition; see www.ippfwhr.org. And Editor & Publisher tells us that in

Long Branch, New Jersey, the Shore Institute of the Contemporary Arts is

displaying “American Comics’ Creators,” a show focusing on the work of “more

than 30 comic book and newspaper comic cartoonists” from Bil Keane (Family Circus) to Will Eisner (The Spirit), through December 23. Elsewhere, the Marine Corps Times reports that a

collection of Bill Mauldin’s original

cartoons, including, it is implied, some of his World War II efforts, is being

exhibited at the Jean Albano Gallery in Chicago through December 30. ... Comic

characters are still among the popular choices for parade balloons, reports Editor & Publisher. Garfield and Snoopy were in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade in New York, and

a For Better or For Worse -themed

float cruised down the street in the Santa Claus Parade in North Bay, Ontario.

... Two graphic novels are on the list of Top Ten Spiritual Books of the Year

from the Detroit Free Press: Sandman: The

Absolute I by Neil Gaiman and Pride of Baghdad by Brian Vaughan and Niko

Henrichon. ... The 2007 Art Festival

of the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Arts in New York has been so

enthusiastically applied to by exhibitors that the organizers have expanded the

venue to put exhibits in the seventh floor Skylight Ballroom of the historic

Puck Building, the traditional Festival site; the panel sessions that usually

take place there will be moved to the MoCCA museum itself, two blocks away at

594 Broadway. The Festival is planned for the weekend of June 23-24. ...

Veteran comic book artist Dave Cockrum died

on Sunday, November 26 from complications due to diabetes. For an appreciation

of Cockrum’s role in comics, and a heartfelt eulogy from Jim Shooter, visit http://scoop.diamondgalleries.com/scoop_article.asp?ai=13938&si=124. I

can’t do better here.

Dynamic Forces will publish a line

of Historical Retrospective Books by Stan

Lee, beginning with Stan Lee’s Guide

to Writing Comics and Stan Lee’s

Guide to Drawing Comics. Lee, remembering the success of his How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, which

he produced with the considerable aid of John Buscema in 1984, is confident of

a best-seller. ... David Remnick, editor

of The New Yorker, has received the

National Press Foundation Benjamin C. Bradlee Editor of the Year Award “for his

work on a magazine that is literary journalism at its best ... a magazine that

meets the ultimate test—its readers look forward to its arrival every week.”

True, for me anyhow. In the same competition, Steve Sack of the Minneapolis

Star Tribune was named the Berryman Cartoonist of the Year for his

excellence in political cartooning, a distinction Sack deserves from the

Pulitzer Committee, too. ... That Norman Rockwell painting that was discovered

behind a false wall in the Vermont home of Henry cartooner Don Trachte after his

death sold at Sotheby’s on November 29 for $15.4 million, a record auction

price for the artist. The painting, “Breaking Home Ties” (the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, September 25,

1954) was voted the second most popular cover in the magazine’s history;

“Saying Grace,” the Thanksgiving cover of November 24, 1951, was the most

popular. For the Trachte tale, visit Opus 181 and 182. ... In

Yemen, a newspaper editor was sentenced to a year in jail for publishing the Danish Dozen, and his paper was shut

down for six months, saith BBC News. The hapless but good-intentioned editor

said he had reprinted the cartoons to raise awareness not to insult Muslims.

Out on bail, he’s appealing the sentence. Two other Yemeni editors face similar

charges.

From Editor & Publisher: The

U.S. Marine Corps presented its William L. Hendricks Founders Medallion to Mutts’ Patrick McDonnell for his help with the Corps’ “Toys for Tots”

program, founded by Hendricks. Among McDonnell’s contributions, the artwork for

the poster. ... Warned that Stephen

Pastis’ Pearls Before Swine strip

would use the words “bite me” in its December 2 release, apparently only two

newspapers requested a substitute strip. Maybe daily print journalism is

becoming more tolerant. Or more licentious. Or clueless. Seems an advance in

civilization, no matter which.

From a September issue of Time: Manga was a $180 million market in 2005. Milton Griepp, CEO of

ICv2, “a pop-culture news site,” said: “Books are not a growth business, but

the manga category has tripled in the last three years. That gets publishers’

attention.” And so American publishers are dashing into the market with manga

of every description, seeking, in particular, the 11-21 year-old female market,

which is “huge,” said Jane Friedman, CEO of one of the dashers, Harper-Collins.

In a hurry to penetrate the target market, American companies are producing home-grown

manga, which provokes an argument from purists who contend that true manga can

be made only in Japan. At Tokyopop, the largest U.S.-owned creator and licensor

of manga, CEO Stu Levy disagrees: “Manga is like hip-hop. It’s a lifestyle. To

say that you can’t draw it because you don’t have the DNA is just silly.”

Meanwhile, at DC Comics, plans are afoot to capitalize on the female appeal of

the manga fad: in May 2007, DC will launch “Minx,” a line of graphic novels

aimed at young adult female readers. The six initial titles include Clubbing, a London party girl solves a

mystery; Re-Gifters, a

Korean-American in California enjoys martial arts; and Good as Lily, a young woman meets three versions of herself at

different ages. Says DC’s Karen Berger, a senior veep: “It’s time we got

teenage girls reading comics.”

Did Avi Arad abandon Marvel for greener pastures? Probably, but why did

Marvel let him go? According to that same September issue of Time (above), it was in order to make

more money on its superhero motion pictures. Marvel is doing just fine, thank

you: its stock has jumped from $1 a share in 2000 to $20, but while its movies

are piling up boodle, Marvel isn’t going to the bank as often as we might

imagine. Ron Perelman, remember, “pillaged Marvel for cash” and sold off much

of the company’s intellectual property. “Because Spider-Man’s theatrical rights

had been sold to Sony, Marvel received just 5% of the $400 million U.S. box

office” from the first Spider-Man movie. “If we wanted to control our own

destiny [that is, collect the revenue that’s rightfully ours], we’d have to

make our own movies,” said Michael Helfant, president of Marvel Studios.

Marvel’s risk-averse board managed to steer clear of the biggest risk by

borrowing a $525 million nest egg to make ten films by 2012. Letting Arad go

was another expense-saving maneuver: “Avi’s contract was up in November,”

Marvel CEO Peter Cuneo said, “and Marvel couldn’t afford the compensation he

can demand. So we thought we’d let him leave on our own terms.” One of those

terms is “that Arad will be involved in at least the first three Marvel

movies.” Some see Arad’s departure as a sure sign that Marvel will soon change

hands again.

The operative mechanism in the movie “Borat” may have its roots in its

star’s dissertation at Cambridge University, according to Brendan O’Neill in The Christian Science Monitor, November

21. The dissertation’s ostensible subject is the alleged alliance between Jews

and African Americans in the U.S. in the 1960s, a time of civil rights

activism. While the claim of an alliance is exaggerated, Sacha Baron Cohen

argues, Jews’ own history of suffering “played a vital role in predisposing

them to identify with oppressed Blacks.” Cohen, a devout Jew who keeps kosher

and observes the Sabbath, notes that Jews may have taken up the Black struggle

because of a Jewish ethic to “know the stranger,” to defend those cast out.

Says O’Neill: Cohen “quotes the Passover command ‘Know the stranger, for thou

wert strangers in Egypt,’ and cites Jewish activists who believe you can judge

a man by the way he treats those who are ‘strange.’ Baron Cohen pretty much has

turned this ancient Jewish ethic into a guerrilla comedy tactic designed to

expose prejudice. His characters are archetypal ‘strangers’: the weirdly

foreign Borat,, the self-ghettoized Ali G, the over-the-top gay Bruno. And

their aim is to provoke reactions to their strangeness. The ‘good guys’ are

generally tolerant ... and the bad buys get hot under the collar. ...” Thus,

“Borat the anti-Semite may be built on firmly Jewish ethical foundations.”

Our esteemed webmaster, Jeremy Lambros, produces two comics.

One, an erstwhile half-page strip in the digest ’zine Disney Adventures, has been bumped up to four pages in the

magazine’s quarterly version, Comic Zone. Entitled Level Up, it features an

ensemble of young gamers and their vicarious (and sometimes actual, right there

on the couch) adventures. The other Lambros enterprise is Domestic Abuse, a single panel cartoon about the attitudes and exploits

of common kitchen implements and household condiments, which can be found at www.GoComics.com, Universal Press’s latest online manifestation.

Click first on “Comics” for a complete list, then scroll down the list to the

D’s. (Yes, you’ll see Rants & Raves in the vicinity, too, a version of the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wurlitzer

torn from the mother lode here at RCHarvey.com, where only you, a

$ubscriber/Associate, can enjoy the Full Treatment. But, as you might say,

we’re branching outwards.)

Fascinating

Footnote. Much of the news

retailed in this segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and

related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve

deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and

lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com.

And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

Further

Ado

A baby, Ronald Knox has said, is “a loud noise at one

end and no sense of responsibility at the other.”

And Dr. Samuel Johnson, a tortured

moralist who also made the first great dictionary of the English language, said

that people more often need to be reminded than informed.

We’re lucky to live in an age when

such bon mots still seem applicable.

EDITOONERY

At

several newspapers recently, editors have solicited political cartoons from

their readers. “Readers as cartoonists? Why not?” asks Dennis Ryerson of the Indianapolis Star. To hear him tell it,

the scheme is merely an extension of letters-to-the-editor. “We welcome the

views of others,” he writes. “Editorial cartoonists do play a special role in

engaging readers. Their visual impact and quick point of view combine to make a

powerful statement.” That’s nice to hear, of course. But, says one editoonist

lately laid off in a tightening budget move: “It’s kinda like just anyone off

the street can do what any editorial cartoonist can do,” and it looks

suspiciously like “an attempt to get free content, no matter how shitty it

looks.” At the Indy Star, staff

editoonist Gary Varvel is still

employed, but he’s taken on the additional task of “coordinating the

reader-cartoon initiative.” A little like signing your own death warrant,

sounds like.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE

The Spirit of Eisner, Loeb and Cooke

Batman and the Spirit is an old fashioned romp, a giddy union and re-union

of too many characters to make much of a story, but, defying the odds, turns

out just fine. The one-shot comic book from DC is intended, probably, to kick

off the latest reincarnation of Will

Eisner’s legendary character—due momentarily—which is both written and

drawn by Darwyn Cooke. Here in the

preamble, Cooke draws a tale written by Jeph

Loeb. Someone at DC doubtless thought having Batman meet the Spirit would

be a good way to bring Eisner’s classic creation into the current DC milieu. On

the face of it, the notion seems not only intriguing but workable: Batman and

the Spirit are both masked vigilantes who often work closely with the city’s

police commissioner, and they’re both somewhat noirish, an ambiance evoked with

lots of black ink, bottles of it, soaking the paper in dark and shadowy night.

They seem to belong together. They don’t, of course: Batman is a serious

pathological crusader, and the Spirit has his tongue in his cheek more often

than not. But Loeb gets them to work together just this once, mustering a

menagerie of menace for the occasion.

The McGuffin is a policeman’s

convention in Hawaii to which both Batman’s James Gordon and the Spirit’s

Eustace P. Dolan are invited. When the criminal element hears that a great

quantity of the nation’s policemen will be assembled, like sitting ducks, in a

distant resort, they all get together, inspired by the Octopus, the faceless

nemesis of the Spirit, to blow up the entire establishment. The Spirit and

Batman, separately, wonder why all the bad guys have disappeared from Central

City and Gotham and pretty soon realize that a dastardly plot is afoot; they

both go to Hawaii. In Hawaii, Commissioner Gordon is seduced by P’Gell, the

notorious femme fatale in the Spirit’s adventures, and Dolan falls under the

spell of Poison Ivy from the Batman oeuvre. Meanwhile, a gaggle of Batman and

Spirit villains have assembled—Croc, Catwoman, the Riddler, Cossack,

Carrion—and Batman and the Spirit set out to discover exactly what the evil

doers are plotting. They first encounter each other whilst lurking in a

darkened place, and since each thinks the other is a bad guy, a fist fight

ensues. Drenched in black, this is a memorable sequence: each panel is like a

momentary flash of light during which we see a fragment of the fight—a swinging

fist, a foot, a flapping cape, an eyeball through a mask’s eye aperture.

Unbeknownst to the entire ensemble, the Joker and Harley Quin arrive in Hawaii

with a plot of their own. The roster of baddies is now complete. Batman and the

Spirit vanquish their foes, of course, and the adventure ends with a chuckle for

literary scholars when Superman shows up as the classic deus ex machina.

The story eventually devolves into a

dizzying charade of characters shedding masks and revealing identities—the

Joker goes to the banquet with a Commissioner Gordon latex face mask, and the

Spirit wears the Batman’s cape and cowl. Any plot that embraces all these

personages and still carries a story is bound to be a convoluted complexity,

more contrivance than drama, and this one is every bit of that. Loeb, clearly

enjoying himself, heaps on even more incident and event. Gordon and Dolan dally

with P’Gell and Ivy, and the Catwoman tempts the Spirit. When the Spirit jumps

into a taxi, he comments that it’s a nice car and he has a friend back in

Central City who’d appreciate it—an allusion to Ebony White, who debuted in

Eisner’s feature as a cab driver, a fact long lost, I suspect, but relished as

Loeb reminds us. Loeb also insinuates the best running gag in the tale when,

upon meeting Batman, the Spirit says: “C’mon—Batman isn’t real. It’s just

something the Gotham City P.D. made up to scare crooks.”At the end, as Superman

flies off bearing an entire yacht of crooks, the Spirit says: “Now, there’s

something you don’t see every day,” and, turning to Batman, he continues, “—and

now I’m supposed to believe there really is a Batman?”

Twice Loeb and Cooke exploit the

duality inherent in the pairing of two heroes by unfolding events in a vertical

stack of parallel panels in which similar events are shown taking place

simultaneously in the Batman continuity and in the Spirit continuity. Cooke’s

treatment of Eisner’s iconic character is not much like Eisner’s. The Spirit’s

mask doesn’t look quite as pasted on as it does with Eisner’s rendering, but

Cooke comes as close as he can with his manner of drawing. I miss the

feathering and trap-shadow shading that distinguished Eisner’s drawing style,

but I never expected to find it with Cooke. I expected Cooke, and that’s what

we have here. We’re accustomed to the animated style in Batman titles, but it’s

still a hurdle to leap with the Spirit. Cooke’s crisp rendering with a bold,

flexing line was never intended to duplicate the appearance of the original,

but he nonetheless evokes it by laying in solid blacks, creating his own

version of the noir atmosphere in Eisner’s tales.

The opening sequence is particularly

delicious. On the first page, Dolan and Gordon frame the tale that will follow

by reminiscing about the time Batman and the Spirit met, and their conversation

takes place in the Kipling Club’s cavernous livingroom, its architectural

features etched in black shadows. The two stand before a roaring fireplace, and

their faces are shadowed and highlighted in the best Eisner manner. Then comes

the best nostalgic gag in the book. The scene shifts to the waterfront where

the Spirit is closing in on some of the ungodly. As he prances across the giant

letters of a warehouse name plate, Pier Sixteen, the bad guys let loose a

fusillade so intense that it knocks down the name plate and unhorses the Spirit.

Turning from that to a full-page illustration, we see the Spirit falling

through the air, surrounded by some of the letters dislodged from the Pier

Sixteen sign—the letters S, P, I, R, I, and T. Eisner would love it.

Next month, we’ll see the first Cooke

solo on the Spirit as that new DC title launches. The old Spirit, the Archive

volumes, continue to be issued regularly. We’re now up to Volume 19, July 3 -

December 25, 1949. By this time, Eisner

had come to realize that Ebony White, his stereotypical caricature of an

African American, was not just comic relief: he was also crude racism. Eisner

began to phase Ebony out of the stories, introducing a white kid, Sammy, whose

bulging cheeks gave him a physiognomy similar to that of Ebony with his giant

pink lips. Ebony makes his last appearance in the story dated September 18,

1949; he disappears quietly between the first page and the last, without

fanfare or farewell. The Spirit continues to run into a catalogue of femme

fatales with picturesque names—Autumn Mews, Vino Red, Lilly Lotus, Flaxen,

Cider Sue, and, for Hallowe’en, a wizened old crone, a witch named Hazel P.

Macbeth, who is running for Miss Rhinemaiden of 1950 (an allusion to the Miss

Rhinegold contest staged annually by a beer brewer in New York). More and more,

Eisner’s stories focus on characters other than his hero; the storyteller,

chafing at the limitations of crime fiction, explores the literary potential of

his medium with O. Henryesque stories. In some stories, the Spirit scarcely

appears. In “Ten Minutes,” Eisner tailors a story to the time it takes to read

it: in the last 10 minutes of his life, a petty hoodlum commits a robbery

during which he unintentionally kills his victim, but before the end of the

tale, the hoodlum is dead, too. The Spirit appears but the crook’s demise isn’t

his doing: the presence of the masked man, however, forces the hood to act

without thinking, and that results in his death. The Spirit volumes continue to

be the best in DC’s archival series. Two things distinguish them: first,

they’re printed on off-white, mat-finish paper, so the pages don’t glare, and

the colors seem somewhat muted compared to the garishness of most comic book

reprint tomes; second, the artwork is probably shot from Eisner’s originals, so

all the fineline feathering is reproduced exactly, without the clotting that

sometimes results when reconstructing the art of Theakstonized old comic book

pages.

The Other Eisner. W.W. Norton, the uptown house that published in

2005 Will Eisner’s last graphic novel, the polemic The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, is

continuing its program to fulfil the last wishes of the legendary cartoonist in

re-issuing all fourteen graphic novels in the Eisner Library, as it had

arranged to do before Eisner’s death in January 2005. The first to be published

(in November 2005) was the hardcover A

Contract with God Trilogy, which collected A Contract with God, Eisner’s first graphic novel, and A Life Force and Dropsie Avenue. For this volume, Eisner supplied more than 20

additional illustrations plus a new introduction in which he tells how the

death of his daughter inspired Contract. Next came Will Eisner’s New York, which

included a chronological quartet, New

York: The Big City (1981), The Building (1987), City People Notebook (1989),

and Invisible People (200). This

volume, another hardcover, just out, includes six new illustrations, “the last

images he ever drew,” according to Robert Weil, the publisher—inked by Peter Populaski. These are some of the

most poignant of Eisner’s tales of New York, “a valentine to the Big City,” as Neil Gaiman says in the introduction—a

vivid demonstration of the dramatic potential of the arts of cartooning, I say.

And the artwork, which I’ve seen only in the pre-publication bound galleys, is

lovingly reproduced, no idle matter because the first section consists of

drawings to which Eisner applied a delicate wash, creating a combination that

often does not survive reproduction. Here, it does very well. According to PW

Comics Week online, Norton will be re-issuing all the graphic novels in

paperback, one every fall. And in the fall of 2008, the publisher plans to

bring out Eisner’s three instructional books: the “classic” Comics and Sequential Art will be

retitled Will Eisner’s Comics and

Sequential Art, and Graphic

Storytelling and Visual Narrative will appear as Will Eisner’s Graphic Storytelling. Both will employ a second

color. Finally, Norton will produce Eisner’s final work, the unpublished Will Eisner’s Expressive Anatomy. Eisner

had completed the pencils; Poplaski will ink them. The plan is to have copies

of the instructional titles in time for the 2008 San Diego Comic-Con.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis

Miller adv.

Tom

DeLay is probably embarrassed. His House district in Texas turned blue.

Democrat Nick Lampson, who had been one of the Hammer’s “re-districting”

victims in 2004, moved into DeLay’s district and took his seat in November’s

election.

TWO CENTS WORTH

The

penny started carrying Abraham Lincoln’s image in 1909 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth. This was the first U.S. circulating coin to bear a

president’s face. Until then, starting in 1859, the penny was embossed with an

Indian head. Lincoln’s likeness was sculpted by victor D. Brenner, and if you

have better eyes than I, you can find his initials at the bottom of Lincoln’s

right shoulder. On the reverse side is the Lincoln Memorial, and if you look

close (with the same magnifying glass you just used on Lincoln’s shoulder), you

can see between the two center columns the famed statue of the seated Civil War

president.

COMIC

STRIP WATCH

Stephen Pastis is still at it. On November 22 in Pearls before Swine, his alter ego

personage is bemoaning the success among readers of Brian Crane’s Pickles strip, so Pig and Rat dress up like Earl and Opal. “I lost my glasses, Opal,”

says Pig/Earl, who is wearing his glasses. “Check your face, Earl,” says

Rat/Opal.

In Opus on November 19, Berke

Breathed started playing word games—anagrams, to be exact. “Tom Cruise”

became “So, I’m cuter.” Ronald Reagan, a darn long era. Salman Rushdie, read,

shun Islam. By December 3, the Anagrammer was up to “God” morphed

anagrammatically into “dog.” Then he wanted to go for “the Prophet Mohammed,”

but Opus quaked in fear: “No,” he shrieked, “newspapers won’t show that

anagram!” But the Anagrammer insisted. “Whisper it,” Opus whimpered. But in the

next panel, Breathed avoids disaster: whatever the anagram of “the Prophet

Mohammed” may be, he obscured it with a crimson scribble. Having dodged one

bullet, he then lined up for another one. Opus turns to us and says: “Folks, as

always, send your comments and complaints directly to my cartoonist,” and he

points to the signature below: Walt Disney, a perfect mimic of the famed

signature. Muslims probably won’t riot in the streets over that, but what about

the Mouse House minions?

BOOK MARQUEE

The

back cover of the book asks a question: “What happens when a shoe-crazy,

lipstick-obsessed, wine-swilling, pasta-slurping, fashion-fanatic,

single-forever, about-to-get-married big-city girl cartoonist (me, Marisa Acocella) with a fabulous life

finds ... A LUMP IN HER BREAST?” One of the things that happened in this case

is a colorful graphic memoir entitled Cancer

Vixen. Another thing that happened in this case is exuberant cartooning the

way exuberant cartooning should be. Suffused with wit both visual and verbal,

the book is a roller coaster read of emotional highs and lows, joy and anger

illuminated on every page by Acocella’s simplest line art. (She has other

styles.) She uses visual symbols like an editorial cartoonist—also diagrams and

charts—to take us, step by step, day by day, through the ordeal of initial

suspicion about the lump, then examination, ascertainment, and treatment of all

sorts. The book is informative in copious detail, explaining every aspect of

her disease and its treatment—with visual aids, naturally. Acocella satisfies

her curiosity, and ours, about breast cancer, but in addition to being curious,

she’s a cartoonist and thinks like one—in visual-verbal terms—as is evident on

every page. She deploys narrative breakdown and page layout as deftly as she

wields her pen, adroitly blending word and picture for comedic purposes as well

as educational ones. And there’s personal drama as well as hilarity: will her

fiancé desert her now that she’s “damaged goods”? It’s great cartooning. Along

the way, we get generous glimpses of her professional life as a cartoonist and

her love life; she is on the cusp of marrying for the first time at the age of

43 to celebrity restaurateur Silvano Marchetto, and by the end of the book,

that’s been accomplished, so her byline on the book acknowledges it: Marisa

Acocella Marchetto, “right now, cancer-free,” she says, “—thankfully.”

QUIPS & QUOTES

From Gore Vidal:

“It is not enough to succeed. Others

must fail.”

“There is not one human problem

which could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise.”

“A narcissist is someone better

looking than you are.”

“Never have children; only

grandchildren.”

REPRINT REVIEWS

The

eleventh compilation of Jim Toomey’s Sherman’s Lagoon is among us. That

means there’ve been ten previous successful compilations. The apparent

popularity is not easy to explain. Sherman is a shark, and the appeal of a

comic strip about a carnivorous fish is not patently obvious. The attraction

does not lie in visual flamboyance: Toomey’s drawing style is assured and more

than adequate but without any flourishes at all, and cartoon pictures of

sharks, large fish, are scarcely artistic challenges. All face and fin and

tail. That’s it. In Sherman’s case, it’s all nose and tail. The graphic

achievement is not inherently impressive. The rendering of one of the

supporting cast, a hermit crab named Hawthorne, is a little more complex, but,

again, drawing crab anatomy, however confidently, doesn’t represent the

accomplishment of, say, the 100th view of Mt. Fuji. No, it isn’t the

pictures that attract Sherman’s Lagoon readership. It’s the humor, and the hilarity is amply displayed in this tome, Planet of the Hairless Beach Apes (128

8x9-inch pages in w/w; paperback, $10.95), a “hairless beach ape” being the

sea-dwelling characters term for human beings.

There are few humans in the strip.

They appear mostly just before Sherman eats them. Sherman has a rapacious

appetite and will eat anything, a tendency responsible for many jokes in the

strip. In this collection, a flock of sheep is marooned on the island, and

Sherman starts eating them. His wife,

Megan, finds a cookbook written by a Buddhist vegetarian and a meat-eating

hunter-rancher and reads some of it to Sherman: “Lambs are intelligent,

sensitive creatures that form complex communities,” she reads, “you can bake

‘em, broil ‘em, skewer ‘em, boil ‘em and chop ‘em up into sausages.” Sherman

says: “Does the whole book read like that?” The comedy here arises in part from

Sherman’s sharkness but also from Toomey’s swipe at the unlikely collaboration

between vegetarians and meat-eaters. And it’s this combination that gives the

strip its unique appeal—a vision of the human sapien as seen from the animal

perspective. Or, rather, the fishy perspective.

Sherman eats nothing but sheep for

several days, and, giving substance to the old expression “you are what you

eat,” he begins to sprout wool and to bleat. He even seems to aspire to change

species. His friend Fillmore the sea turtle tries to talk him out of his

fascination with sheep. “They are not you,” he says; “this is not your tribe.

You’re a fish. See that sheep on the left,” he continues, pointing off-panel;

“ask yourself—could you date her?” Sherman says: “The cute one? Sure.” Which

proves, I suppose—assuming that it needs proving, which I doubt—that we’ll be

attracted to anything that’s cute, regardless of species.

Toomey feels a shark’s reputation is

not entirely deserved. “Sharks have an image of being tough and ferocious,” he

told Theresa Winslow at the Annapolis

Capital, “but they are in fact delicate and endangered. Sharks are unique

and streamlined and beautiful and efficient, and I like that as an artist and

an engineer.”

Toomey comes from a family of

engineers, and he has an engineering degree, but he turned to cartooning after

trying a couple of jobs as production manager for museum exhibit companies.

When mulling over a subject for a comic strip, he remembered seeing a shark

sunning itself in a lagoon when he was a kid. A strip about a shark combined

all the things Toomey liked: drawing, the ocean, and humor with a sense of

environmentalism. He self-syndicated the strip at first, running in about 15

newspapers; now syndicated by King Features, Sherman’s Lagoon appears in about 220 newspapers.

The main characters are named after

streets in San Francisco, where Toomey used to live. He now lives in Annapolis,

and his wife, Valerie, runs a children’s clothing and toy shop downtown. Her

favorite sequences involve Sherman trying to figure out his wife, which, she

believes, capture some of the fine points about relationships. “It’s true,” Mrs.

Toomey says, “whether it’s fish or people.”

“For me,” says Toomey, “the

characters are different facets of my brain. Sherman is the impetuous side;

Fillmore, the intellectual side; Hawthorne, the cranky side; Megan, the

feminist side.”

And all of his sides encounter in

the strip the various phenomena of life on land as experienced by all of us.

Sherman gets a computer and has trouble, so he phones tech support, which

results in the usual run-around. He finally gets “Greg,” who asks what his

problem is. “It’s my e-mail,” says Sherman; “I’m not receive any. Haven’t for

days.” Says Greg, with the usual tech support helpfulness: “Have you considered

that maybe you don’t have any friends?” Says Sherman: “Listen Greg, I’m capable

of biting you in half.” Says Greg: “Sir, this is tech support. I hear scarier

threats from my mom.”

Sherman aspires to better himself

and starts reading a book. Fillmore is astonished, but Sherman responds with

aplomb: “The new sophisticated Sherman happens to love literature,” he smirks.”

“He does, eh?” says Fillmore. “Yeah,” says Sherman; “one thought though—with no

commercials, how do you know when to potty?” Fillmore, to himself: “Rookies.”

Sherman scoffs at his son playing

with a doll, but Megan defends the practice: “This is a guy doll,” she says;

“fathers are using guy dolls to help pass on manly traits to their sons. It’s a

new age parenting thing. Look,” she continues, Fillmore the sea turtle, talking to Hawthorne the hermit crab, says: “Now hybrid cars are all the rage. Turtles are the original hybrids, you know.” Oh, really?” says Hawthorne. “See that shell on my back?” says Fillmore; “wherever I go, I’m always home. Now that’s a hybrid.” Hawthorne disagrees: “That sounds more trailer park than hybrid,” he says. Says Fillmore: “We’re sticking with hybrid.”

The First Tina. Tina is one of those comic strip characters with a

tiny, tiny body and a big head. This character design went out of style just

before World War II, but it’s coming back in fashion because newspaper comic

strips these days are being printed so small that there’s no room for the

drawing after the speech balloons are lettered. Tiny-body characters leave more

room for speech balloons; and the large heads are perfect for putting large

faces on, faces large enough to register emotions appropriate to the jokes

being perpetrated. The advantages of this character design became apparent in

the tsunami success of Peanuts. In

addition to a large head, Tina has a hair-do that appears to end in a matched

pair of buns, if that’s the right technical term for the bunches of hair that

women wad up into a ball against the backs of their heads. Tina is the title

character in Tina’s Groove, a strip

always signed “Piccolo,” one of the

creating cartoonist’s names. The other name is “Rina,” which suggests, correctly, that the cartoonist is female.

She is also, as it happens, of somewhat petite stature, but that has nothing to

do withTina’s size. Tina is a young unmarried woman working as a waitress in a

diner, another relic of a bygone age but lively enough here. A comic strip

about a youngsingle working woman created by another young woman (who was,

whenthe strip started, also single) seems deliberately contrived by a

syndicatemarketing department to take advantage of the demographic-pleasing

impulses that inspire newspaper editors everywhere. One might suppose that Tina’s Groove is a second Cathy. And I suppose some of the more

than 100 subscribing newspapers signed up for the strip for exactly that

reason. It’s accurate to say that Tina’s

Groove reflects a female sensibility, but it’s also funny. And it’s rendered

with a brush, which gives the linework a visual interest entirely lacking in

such endeavors as Cathybert.

Here is a sampling of the comedy

from the first collection of the strips, Tina’s search for romance is often

frustrating. At a nice patio restaurant, her escort takes her hand and says,

“Oh, Tina—I knew from the moment I met you that I wanted to spend the rest of

my weekends with you.”

Other members of the cast are also

sources of comedy. Suzanne displays an inexorable logic explaining to Tina why

getting her credit card stolen is actually a good thing: “The person who stole

the card is spending less with it than I normally spend. I’m saving a bundle!”

she says. Tina’s waitress friend Monica decides that it’s true “that time heals

all wounds.” She explains: “Last week, I was terribly hurt by this letter from

my boyfriend, and today, the paper cut is healed.” Women’s fashions sometimes

inspire a jaundiced reaction. At a boutique, Tina inspects a dress with a high

neckline and a low hemline and says, “I believe I’ve just discovered the

antidote for viagra.” Encountering a display of garments called “granny

panties,” Tina decides that lingerie designers must be “thinking globally”

because the unattractive underwear is an obvious “attempt to decrease the

population growth.”

Life in a quick-order diner also

inspires comedy. Here, for instance, is an unkempt, bearded, hairy man who

complains to Tina that “there’s a hair in my salad.” Or the man who explains to

Tina about the tape on his wife’s mouth: “It’s the Dieter’s Patch—you wear it

before meals to reduce food intake.” At the Take Out counter, Tina cheerfully

says to a hippie-looking woman: “It’s the last slice of key lime pie, and it

has your name on it.” The hippie stares at the pie for a panel and then says,

“Man, I must be on some kind of weird mailing list.” One week is devoted to a

series entitled The New Girl Won’t Last. The new waitress tells a lady customer:

“I highly recommend the white wine ... because it won’t stain as bad if I spill

it on you.” The customer apparently left in a huff because in the next panel,

Tina is saying to the new girl: “Your resume says you have experience serving

wine.” “Did I mention,” says the new girl, “it was a bad experience?”

Outright word play tickles the

risibles, too. Suzanne, flustered, yells at her boss at the diner: “Rob—don’t

talk to me when I’m at my wits’ end!” Rob thinks it over for a moment, and then

turns to Tina and says: “Is Suzanne ever at her wits’ beginning?” That’s funny

enough in itself, but Piccolo adds another chuckle with Tina’s response: “It’s

a very narrow window of opportunity.” Suzanne regularly meditates of an

evening, and once she tells Tina, “Last night, I suddenly saw the light.” “What

was it like?” Tina wants to know. “There was way too much magenta in it,” says

Suzanne. Another time: “I spent the weekend organizing my personal files so I

can have a semblance or order around here,” Tina tells Suzanne, “—the whole

weekend just for a semblance of order. Imagine how long

it would take if I aimed for real order.”

Not much in Tina’s Groove about the annual spring search for a

figure-flattering swimsuit when your figure is larger than the suit. No Cathy formula jokes at all. Just good

comedy.

OLD RISQUE JOKES FROM THE PRAIRIE HOME

COMPANION MOVIE

“I think my wife died.”

“Why do you think that?”

“Well, the sex is the same but the

dishes in the sink are stacking up.”

Second

Joke:

“What’d the elephant say to the

naked man?”

“Dunno. What?”

“It’s cute, but can you really

breathe through that thing?”

The

Kind We Love Here at the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wurlitzer (but not from the

Prairie Home Companion Movie):

Evidence has been found that William

Tell and his family were avid bowlers. However, all the league records were

unfortunately destroyed in a fire. So, we’ll never know for whom the Tells

bowled.

One

more:

A man rushed into the doctor’s

office and shouted: “Doctor! Doctor! I think I’m shrinking!”

The doctor calmly responded: “Now,

now—settle down and wait your turn. You’ll just have to be a little patient.”

Okay,

I lied; here’s another:

A nurse stood by quietly while the

doctor yelled, “Typhoid! Tetanus! Measles!” A new nurse observing all this,

asked: “Why is he doing that?” The other nurse replied, “Oh, he just likes to

call the shots around here.”

GRAFICITY

Fun Home

It’s

no good extolling Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home as a literary achievement

without taking into account the role of pictures in this graphic memoir. The

maturity of comics as literature is evident, first, in the book’s narrative

technique. Bechdel the cartoonist’s autobiographical recollections of her

childhood and youth as Alison, the daughter/narrator, do not form a chronology:

instead, they cluster thematically in chapters that examine her father’s role

in the family and his daughter’s discovery of her homosexuality. In successive

chapters, Bechdel returns, again and again, to pivotal events, each time

exploring various memories that resonate from aspects of each of them. Her

protagonist is her father, a highschool teacher of English and, part-time, the

small town’s only undertaker, who spends his spare hours meticulously restoring

the family’s 1867 Gothic-revival home, working in the garden, or reading great

works of literature. Alison’s mother, also an English teacher, working on her

master’s degree and acting in community theater, is, compared to her father, a

blank; her two siblings, likewise. We learn about the father’s obsessive

perfectionism in restoring the house in the book’s opening pages, and Alison

also tells us, off-handedly, that he killed himself and that he had sex with

teenage boys.

When she returns to his alleged

suicide, we learn that his death may have been accidental: he jumped,

backwards, into the path of an oncoming truck and was killed. About his

homosexual adventures, however, there is little doubt. He was a closeted gay

all his life, but his wife knew, and she tells Alison soon after Alison

discovers her own sexual orientation as a lesbian, which she does when she goes

away to college. There, like any dedicated book lover—she is, after all, her

father’s daughter—she learns about lesbianism by reading about it first rather

than by experiencing it with someone. When she tells her parents, they react

like the two somewhat liberal intellectuals they are: the mother, without

overtly condemning her daughter’s waywardness, hopes she is mistaken; her

father, his own orientation still a secret from the daughter, announces his

belief that everyone should experiment. “It’s healthy,” he says. Almost

immediately thereafter, her mother tells Alison of her father’s predilection.

Upon subsequent revisitings of these events, we learn that her mother started

divorce proceedings soon after learning of her daughter’s homosexuality, and

then, just two weeks later, her father is killed by the truck.

As Alison circles again and again

the key events in her life, she comes closer and closer to the preoccupation

that compels her as a person and motivates her art—her desire for a closer

relationship to her father, who, as she establishes very early, was distant

emotionally, seldom, if ever, displaying affection for his wife or children.

When she learns of his homosexuality soon after acknowledging her own, she

hopes the coincidence will establish a rapprochement otherwise missing in their

relationship. Instead, he dies. Alison assumes a cause-and-effect relationship

from a sequential one: in her imagination, her revelation seems to have caused

his death.

In the first scene of the book,

Alison propounds a mythic kinship with her father, evoking Daedalus and his

son, the doomed Icarus, who flew too close to the sun, which melts the

artificial wings his father had devised for him and sends him plummeting from

the sky. Her father, Alison says, embroidering the allusion, was a master

artificer, “a Daedalus of decor” in his restoring passion. But, she goes on,

ominously at this early stage in the book, “in our particular re-enactment of this

mythic relationship, it was not me but my father who was to plummet from the

sky.” The book is laced with other literary allusions—to Henry James, F. Scott

Fitzgerald, Shakespeare, Proust. Given her father’s involvement with

literature, the maneuver lends the narrative an appropriate ambiance. Long

before the end of the book, we know her father’s favorite novel is Ulysses, James Joyce’s portrait of a

complete man. “Ulysses,” Joyce told the artist and critic Frank Budgen, “is son

to Laertes, but he is father to Telemachus, husband to Penelope, lover of

Calypso, companion in arms of the Greek warriors around Troy, and King of

Ithaca.” In his famed novel, Joyce intended to show “the complete man,” man in

all his roles, “from all sides.” And in Joyce’s enterprise, Daedalus again

appears, this time as a young man, Stephen Dedalus—a son—whose odyssey results

in his finding a spiritual father in the novel’s Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, the

cuckolded husband of the affirmative Molly, earth mother of us all. Fun Home moves from the mythic to the

spiritual, but the flywheel of its dynamic is Alison’s search for something

real, a tangible relationship with her father.

The strongest thematic current in

the book is the deceptive spell of appearances. The name of the book is the

first clue: “fun home” is the Bechdel children’s mocking shorthand for their

father’s “funeral home”occupation. The label that cartoonist Bechdel puts on

the cover for us to see, the “fun home,” is not the reality she shows us

inside, which is scarcely fun. Moreover, the painstakingly restored house the

family lives in “is not a real home at all but the simulacrum of one, a

museum”; and the family, “a sham.” In the father’s passion for restoration,

Alison sees telltale evidence that her father was “morally suspect” and had “a

dark secret,” saying: “He used his skillful artifice not to make things but to

make things appear to be what they were not.” This caption runs over a

page-wide panel showing her father taking a photograph of his family, an

idyllic tableau followed immediately by another, captioned: “He appeared to be

an ideal husband and father, for example, but would an ideal husband and father

have sex with teenage boys?” The mother’s passion for the theater, for

play-acting, is another manifestation of the artifice of appearance. And in

real life, she plays a dutiful and loving wife even though she knows her

husband prefers sex with other males. The father’s death is another deceiving

appearance: he seems to have been killed accidentally, but his daughter thinks

it was suicide. Finally, the father’s homosexuality is the central deception in

the book: he appears to be what he is not, “an ideal husband and father.” By

this route, homosexuality itself acquires a cloak of deception: homosexuality

is the reality contradicted by appearances. Gay people are not the sexual

personalities their apparent genders announce to the world.

Alison’s search for rapprochement

with her father thus becomes a metaphor for her search for peace of mind about

her own sexual preferences. She needs from him some sort of sign of approval or

acceptance. The closest she comes is a conversation the two of them have in the

car on the way to a movie one night a few weeks before he was killed. “When I

was little,” her father says, rather emotionlessly, “I really wanted to be a

girl. I’d dress up in girls’ clothes.” And Alison says: “I wanted to be a boy!

I dressed in boys’ clothes.” Pause. Then the telltale appeal for recognition:

“Remember?” This barren but revealing exchange is not, alas, “the sobbing,

joyous reunion of Odysseus and Telemachus,” Alison notes wryly in captions

accompanying the visualization of the episode. “It was more like fatherless

Stephen and soulless Bloom having their equivocal late-night cocoa at 7 Eccles

Street. But which of us was the father?” she continues. “I had felt distinctly

parental listening to his shamefaced recitation.” And here, the function of Bechdel’s

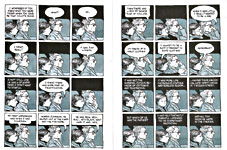

pictures is crucial. The conversation is depicted in two facing pages, twelve

panels of uniform composition on each page: we look into the car from the

window on the passenger side, Alison in the foreground, and her father beyond

her at the wheel of the car. The night outside is evoked with a black

background hovering around the images of the father and his daughter. The

monotony of the layout emphasizes the emotionlessness of their exchange.

Alison’s thoughts appear in white letters against the black. Her father’s

facial expression and his posture never change, suggesting the absence of

emotion in his remarks. Alison, in contrast, gestures and looks around, her

eyes, opening wide or squinting, accenting her comments and registering her

reactions to what her father says.

In the best works of the

cartoonist’s art, pictures blend with the words to create a meaning neither

achieves alone without the other. In that idyllic family tableau that Bechdel

shows her father photographing, the picture shows us one thing—the ideal; the

words announce the fraud. The picture without the words sustains the illusion;

the words without the picture say nothing about the Bechdel family being the

“sham.” Together, the picture and the words create the reality of the family as

Alison understands it. Bechdel’s attention to visual

details gives endless nuance to her tale, usually a humorous embellishment. In

the picture of her family at church, notice that her father is eyeing the choir

boys as they pass—just as the accompanying caption reveals his sexual interest

in them. Alison, standing next to her father, also looks at the boys, but not

with the same interest. She seems bored, an emotion suggested by the depiction

of her brother next to her: he is clearly nearly overcome with ennui, his eyes

closed as if asleep, and his posture is the mirror image of Alison’s. The

visual details in the backgrounds of Bechdel’s pictures usually reward our

attention with the quiet hilarities of the human comedy.

The information conveyed by the

visuals is not always subtle. In the book’s most outrageous blend of word and

picture, Alison records an early lesbian love-making with captions that evoke

Odysseus in tandem with pictures that give the verbiage a musky double entendre

that is altogether missing in either words or pictures independent of each

other. “In true heroic fashion,” she writes, “I moved toward the thing I

feared”; the picture shows her face hovering over her lover’s naked crotch. The

verbal paean continues: “Yet while Odysseus schemed desperately to escape

Polyphemus’s cave, I found that I was quite content to stay here forever”; and

the picture shows Alison up to her nose in the honeypot of her lover. For the book, Bechdel has simplified

her usual drawing style, eliminating the cross-hatching and slant-line shading

that we find in her comic strip, Dykes to

Watch Out For. Her line is simple, unadorned, flexing slightly but not

obtrusively, a little bolder in outlines than in details. Her

draftsmanship—anatomy, composition—is confident, accomplished rather than

adequate; the pictures, nearly a tour de force of plain-line technique. In

place of linear texturing, she has deployed a delicate gray-green wash, tinting

the entire enterprise with a low-key hue.

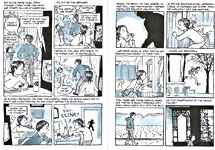

In Fun Home, Bechdel often deploys her visual-verbal resources to

create a tension that underscores the theme that things are not always what

they seem or what we might want them to be. In a long sequence early in the

book, the captions drone on, comparing the Bechdel home life to that of Jimmy

Stewart’s family in “It’s A Wonderful Life” and to the mythic life of Daedalus.

The pictures accompanying the captions show us what Alison means when she says

Stewart’s yelling at his family in the movie is “out of the ordinary.” The

pictures present an episode of Alison’s home life, complete in itself: her

father’s fit of temper causes her to break some crystal she’s handling and,

fearing her father’s reaction, she flees the house. The captions, meanwhile,

carry on about Daedalus’ famed labyrinth, concluding with a speculation about

whether Daedalus was “stricken with grief when Icarus fell into the sea? Or

just disappointed by the design failure?” The prose of the captions offers one

story; the pictures, another. Together, they juxtapose a fiction and a reality,

myth and fact, a happy abstraction and a grimmer actuality. Alison frequently shadows her prose

with her pictures, telling two tales simultaneously, juxtaposing two

realities—two appearances?—which suggests that one may be more real than the

other. Or, perhaps, sometimes both are equally real. In a sequence at the end

of Chapter 3, the captions fantasize about Alison’s father and F. Scott

Fitzgerald, imagining a mystic connection between the two. The pictures,

however, show us an entirely mundane incident, Alison asking her father for

money to buy some new Mad books. The

episode concludes with a telling picture: we peer into the house from outside,

seeing Alison and her father in the same room through two separate windows. The

mini-essay of the captions, meanwhile, has reached its heartbreaking

conclusion: that she persisted in believing that she somehow caused her father

to commit suicide because it created a bond between them, a connection she

longed for all her life. As we read these words, we see the father and his

daughter, bonded, ironically, by the composition of a picture that completely

separates each from the other.

In creating the book, Alison’s method

doubtless fostered the frequent occurrence of such double-vision passages of

prose and picture. “The first thing I do,” she told Margot Harrison at

sevendaysvt.com, “is I write on the computer in a drawing program, which

enables me to make these little text boxes and move them around, make my panel

outlines” without any images. Then she adds pictures, sketching into the panels

on the preliminary layout of the page. A cartoonist’s sensibility kicks in

naturally, then, resulting in pictures that have an ironic or satiric

relationship to the verbiage. But however accidental the emergence of the

double-vision sequences, they are integral to the meaning of the book as a

whole, establishing a pattern of appearance and contradictory or alternate

realities.

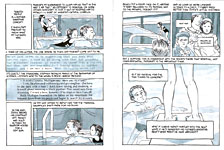

The culminating event to which the

narrative wends is a Joycean meeting between father and daughter, a spiritual

sharing, which, at last, is achieved more in Alison’s memory than in fact.

In the book’s last sequence, Bechdel returns to Joyce’s Ulysses to marvel at her father’s staying in the closet all his life. Referring to Molly Bloom’s passionate and sexual affirmation of life, Alison writes about her father: “How could he admire Joyce’s lengthy, libidinal ‘yes’ so fervently and end up saying ‘no’ to his own life?” The last three pages of Fun Home take place in a swimming pool, where Alison’s father is apparently teaching her to swim. Or encouraging her to dive off the diving board.

Alison admits her claim that her father is gay “in the same way I am gay, as

opposed to bisexual or some other category, is just a way of keeping him to

myself, a sort of inverted Oedipal complex.” In the last analysis, however,

“spiritual paternity,” like that between Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom, is

more important than “consubstantial” paternity. She depicts her younger self

poised on the diving board, her father in the water beneath her, and concludes:

“In the tricky reverse narration that impels our entwined stories, he was there

to catch me when I leapt.” The picture shows her jumping off the diving board

and her father with his arms up to catch her.

But did he catch her when she leapt,

jumping from straight life into gay life? Very little in the book supports that

conclusion. In fact, the book is about her longing for him to be there and

being perpetually disappointed that he never was. Or was he? Throughout the

book, Alison returns again and again to aspects of her father’s life and their

relationship. Gradually, through repeated approaches, she strips him of his

pretenses, of his artifices. But she clearly loves him, and it’s his approval

she wants. That tenuous conversation in the car comes close but it’s not

enough. By the time Bechdel in creating the book gets to the last pages, she

has been back and forth over aspects of her father’s life, and her own, several

times, entwining their stories in tricky reverse narration. In the book—in her

imagination—he is a constant presence. He is “there” in her imagination if not,

actually, in her life. But his imagined presence persuades her that he has been

“there” all along: that he caught her when she leapt, even though, as we well

know, he didn’t.

Having lived, with Alison, through

the elaborate charades of the book, the juxtapositions of alternate realities,

of appearances and contradictory realities, we are ready, as is she, to accept

the reality she constructs for us, and for herself. The last sequence in the

book reveals, in its allusions to Joyce, the book’s narrative strategy: Alison,

failing to achieve a genuine connection to her father despite their shared

homosexuality, consoles herself with a spiritual relationship. The book’s last

caption is the conclusion in this line of thought. But it is false. Like the

book itself, the assertion on the last page is a devout wish but not a fact, an

appearance but not a reality.

The reality is in Alison’s basement

studio. Rachel Deahl of Publisher’s

Weekly visited the cartoonist in her lair. “I stand in her workspace and

look at the rows of books lining her shelves. They remind me of the panels in

her book, the pictures of her reading and her father reading, of them sitting

in that massive house surrounded by print and pages, skirting discussions of

their own lives by talking instead about Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus,

Odysseus and Penelope. Then I notice it. It’s a black-and-white photograph of a

young man. He’s handsome, clean shaven and smiling. He looks familiar, and I

think I recognize him from the drawings. I begin to ask, ‘Is that ...’ ‘That’s

my father,’ Alison says. It’s the only framed picture in her work area and one

of the few in the house. But that seems as it should. After all, who could have

watched Alison through this process other than her dad?” Her father is still a

presence in her life, still “there,” but only in a photograph, an appearance.

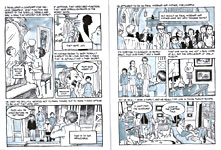

While homosexuality forms the core

of otherness at the thematic center of the book, Fun Home could well be a tale of adolescent alienation. In the Bechdel

household, each family member is isolated from the others, each absorbed in his

or her separate pursuit, a circumstance the cartoonist dramatizes with a

telling cut- Judging from the book, Bechdel never

seems to have felt hesitant about her homosexuality: she apparently accepted

her sexual orientation as a simple fact of life almost from her first awareness

of it. She was about twenty when her father was killed, and she launched her

alternative newspaper comic strip within a couple of years. Its title, Dykes to Watch Out For, is not just

unabashed: it’s defiant. Neither unabashedness nor defiance are marks of

hesitancy or awkwardness; both are flat assertions. At first, when the strip

started in 1982, it took the form of weekly (or bi-weekly) commentary on

various aspects of the human condition—the joys of couplehood, “the rule”

(never go to a movie unless it has two women in it who talk to each other about

something other than a man), the party, great romances (“that never were”), the

first sleepover, politi-cola (“the birth of an activist”), summer grooming tips

(“at the music festivals, braid your armpit hair”), and so on. In “Depression,”

Bechdel speculates on the condition and its causes. Depression may be brought

on by hormones or “because you don’t have a girlfriend ... or it’s the

inevitable result of living in a depraved society during the nuclear age” (the

caption under a picture of Reagan on tv, saying, “I believe in Armageddon”),

but “it’s well known that even women with rich lovers and no political

awareness are often depressed!” She illustrates various possible remedies—increasing

sugar intake, sex, reclusive behavior—“but nothing works except waiting for it

to pass ... one day, just as inexplicably, you will wake up in a good mood.”

Eventually, individual characters

emerged from the nameless milieu Bechdel began with, evolving into the current

manifestation with a cast of dozens of diversities, including various racial

minorities and a lesbian (or bi-sexual) who has a child by her male housemate.

The presence of personalities pretty soon produced plots and stories, which are

now continuing from week-to-every-other-week, exploring the ever-changing

combinations of lovers, politics and social issues, and such personal trauma as

breast cancer. Bechdel’s drawing style at the beginning deployed a fragile line

of unvarying thinness and solid blacks deftly spotted throughout. The line

acquired greater confidence over the years, becoming bolder when outlining

figures, and Bechdel began using gray tones as well as a variety of texturing

devices. Dykes is now one of the

handsomest comic strips around, in or out of the alternative newspaper

universe, and its storylines reflect current political events as well as social

consciousness and personal crises. At least 11 reprint volumes have been

produced; see www.amazon.com for a list. Doing the strip

undoubtedly gave Bechdel the creative confidence to undertake the longer work

of Fun Home, but the two enterprises

are not at all alike in theme or substance except that each is assured

cartooning about aspects of the human condition that matter. Serious literature

for mature readers for whom sex is only a part of adulthood.

NOTES ON THANKSGIVING

Cartoons

Championed? Not Much.

The

so-called “cartoon issue” of The New

Yorker, an annual event at this time of year since 1997, continues to be a

disappointment. It’s not the quality; the number of cartoon captions that make

comedic sense without the pictures is not, it seems to me, as high as it

sometimes was, and that strikes a blow on behalf of the visual-verbal blending

that is the essence of cartooning. In that respect, the “cartoon issue” is

satisfying. Nor is my disappointment a result of the quantity. There are more

cartoons in the “cartoon issue” than in the usual issue of the magazine. The

typical issue offers about one cartoon for every 6 to 8 pages. In the

“anniversary issue” last February, the ratio was one every 4 ½ pages. This

year’s “cartoon issue” runs one per 3 ½, a satisfyingly high rate, achieved by

reason of an 18-page section called “The Funnies.” Four of the pages are devoted

to 9 previously unpublished drawings by B.

Kliban. Roz Chast has a 2-page comic strip, and Matthew Diffee offers 2 pages of realistic bird drawings with

humorous text in the guise of A Guide to

City Birds: “Josh Everett, Snow Goose, likes travel, good food ... About

Me: I came here on a southbound stopover in ’99....” Leo Cullum has a 2-page panoramic cartoon on security at airports

(a sign says “checked baggage”; another sign right below it says “plaid

baggage”), and two pages are devoted to comical explanations of some of the

more baffling cartoons published in the past year. Only 6 of the 18 pages are

devoted, strictly speaking, to a feast of single-panel gag cartoons, 16

cartoons total. All of this is to the good: it’s gratifying to have a major magazine

heralding the useful hilarities of cartoons in this fashion. But I’m

disgruntled because again this year the “cartoon issue” does not live up to the

promise of the first “cartoon issue.”

The inaugural issue published at

least two text pieces about cartooning. The artform was thereby celebrated not

merely recognized. And I persist in hoping that The New Yorker, a periodical distinguished by a long record of

publishing superior gag cartoons as well as superior prose, would make its

annual fete a more extravagant party. It could, for lack of any imaginative

option, publish short biographies of some of the medium’s masters—Harvey Kurtzman, E.C. Segar, Walt Kelly.

This year, the magazine could have run a review of the “Masters of American

Comics” exhibition taking place in two of the city’s museums. Or it could have

examined the role of Jewish creators in the history of comics, the subject of

another exhibition currently in the city. Or it could have mentioned and

reviewed the other comics exhibitions in the city these days, the ones I

mentioned in our Nous Report. For The New

Yorker to slide by its annual celebration of cartooning without devoting

any text to the subject is a little like Playboy (coincidentally, the only other respectable venue for gag cartoons) producing

its Playmate of the Year feature with photographs of a fully clothed member of

the opposing sex. In theatrical terms, it just doesn’t fill the bill.

Then we have Chris Ware’s covers, which the management of the magazine treats

with a disdain akin to the benign neglect it inflicts on cartooning generally

by not talking about it. There are five Ware covers, which The New Yorker, in its usual pince-nez art critic mode, calls “a work in five parts.” Although this issue is dated the

week after Thanksgiving, the five-part cover has “a Thanksgiving theme.” “Four

of the parts are magazine covers,” the deliberately obfuscating explanation

continues, “and the fifth is a comic strip. Subscribers will receive one of the

four covers.” I’m a subscriber, but I got the comic strip “part” not a “cover”

part, a direct contradiction of the editorial intention, I gather. Each of the

five parts commemorates an aspect of the holiday: Stuffing, Conversation,

Family, Main Course, and Leftovers. Visually, the five-part work is a

progression: starting with a full-page illustration, the parts get steadily

smaller, dividing first into two panels, then four, then sixteen, then a

collage of 256 individual pictures. The comic strip, entitled “Main Course,” is

a 4x4 grid of four tiers of four panels each. Twice during the strip, Ware

divides a single panel into four equal parts, a maneuver he frequently deploys.

The actual artwork, another instance of Ware’s meticulous geometric diagraming,

is on a miniature scale, which means the figures are often minuscule to the

point of near invisibility; the lettering, likewise. The cover perpetrates the

usual New Yorker insult: the address

label is pasted on the lower left-hand corner, which, in this case, obscures

two of Ware’s sixteen panels.

Ware’s art, as always, is so

pristine it is antiseptic albeit quite pleasing as wallpaper, but his comedy,

which arises entirely from the titles he gives each of the “parts,” is pure

cartooning. The two-panel “Conversation,” for instance, depicts two family

gatherings around the festive board: in one, family members seem to be talking

to one another; in the second, they are all watching a football game on tv. The

same nihilistic note is sounded on the “Family” cover: in four separate

cartoons, young people have deserted the family hearth on this holiday,

complaining, variously, of ways their families have abused them. In “Main

Course,” a pigeon is run over by an SUV. All of the covers are on display at www.newyorker.com, alas, another disappointment. The fifth “part,”

entitled “Leftovers,” is a collage, a scrapbook, of visual memories of a

brother killed during World War II. Many of the pictures are microscopically

tiny, and the magnifying device on my computer enlarges only a portion of the

artwork, and although Ware designed the piece to be viewed on the Web using the

scroll bar, I can’t find a scroll bar on the window displaying the art, so I

can’t read or view all of it. Bittersweet, like most of Ware’s wares.

In an audio interview on the

website, Ware discusses his five-part “cover,” which, it seems, deliberately

reflects his somewhat jaundiced view of Thanksgiving. He denies that the

five-parter is intended as a political statement. “I’m not anti-turkey,” he

says; “I’m pro-turkey.” And then the give-away: he’s a vegetarian, and he

confesses to seeing a bitter irony in Thanksgiving’s “inherent brutality [as]

ritualized in the sacrifice” of turkeys. With this as preamble, the “Leftovers”

becomes a highly charged political comment: in time of war, to reflect upon the

loss of a relative in a previous conflict is surely to condemn the

senselessness of the current bloodshed in Iraq. Ware’s remarks during the

interview work in the aggregate much like the visual vignettes that make up his

cartoons. Recalling Ben Katchor’s goal of making cartoons with “the density of

a novel,” Ware says he researched the World War II material extensively,

discovering, to his surprise, that many soldiers drew cartoons on their letters

home as if cartooning were a skill everyone exercised, not just professional

cartoonists. He felt obligated to spend the time on research in order to do

justice to the subject, and he clearly enjoys lavishing hours and hours on his

cartoons. In a self-deprecating aside, he realizes the humorous consequences of

his painstaking devotions: “By the time you’re done, you’re ten years older,”

he said, “and you wonder, Where did my life go?” Taken all together—from

“Stuffing” to “Main Course” to “Leftovers,” from the pictures to his own

comments about them—Ware’s commemoration of Thanksgiving is not so much about

giving thanks as it is about indicting a blood-thirsty warlike culture. Where

do our lives go?

’Bye, Fats

A Personal Note

It

was a disorienting sensation, horror in a minor key. I was watching NBC’s

evening news on Tuesday, October 17, when suddenly Brian Williams started

talking about someone who had just —something, I missed it because I was trying

to make sense of the images. Behind Williams was a photograph of a handsome man,

and underneath the name “Glenn.” In another second, I realized it was a picture

of Christopher Glenn. I didn’t recognize him right away because he was wearing

glasses in the picture, and I’d never seen him wearing glasses. And he was

older: I hadn’t seen him for 15 years or so.

My wife said, “Isn’t that Chris?”

“Yes,” I said and shushed her so I

could hear.

What was Williams saying? Chris

Glenn, who had reported, written, and anchored CBS radio news programs for 35

years had died “suddenly” last night in a Norwalk hospital. “He was

sixty-eight,” Williams said. Chris was a CBS newsman but here was NBC doing an

obit. Why the attention? Because Chris was an award-winning broadcast

journalist who’d been on the air for many years, a widely respected colleague.

Cartoon fans will know him if they ever watched Saturday morning cartoons on

CBS: Chris was the reporter/narrator of “In the News,” a series of

two-and-a-half-minute current event broadcasts spliced in between cartoon

programs. Chris was the voice of the Emmy Award-winning program for its entire

15-year run, 1971-1986.

“He was to be inducted into the

National Radio Hall of Fame in Chicago in two weeks,” Williams finished. Later,

I learned it was cancer. Of the liver.

Shocked and angry, I thought: he

just retired last February. He didn’t have time to enjoy his retirement. But

then, what would he do? Chris was hyper-active. One morning he got up and tore

down a wall in his house because he had an idea for re-decorating the place and

the wall was in the way of the plan. When I’d heard he was retiring, I couldn’t

believe it because I couldn’t see him lounging around enjoying the leisure.

Chris was not a man of leisure. I phoned him, and we brought each other

up-to-date a little more than our anyule exchange usually did. He planned to do

voice-overs, he said. Didn’t want his “pipes” to get rusty—that distinctive

baritone rumble that a co-worker, Greg Kandra, called his “cognac and cigarette

smoke” voice. On the air, Chris pitched his voice a little lower than in

ordinary conversation. And before flipping on the mic—I’d watched him—he’d

clear his throat, a robust cough or two.

We called each other “Fats.” It was

a no-longer-sensible remnant of an antique vaudeville joke we’d both enjoyed

when we were in college at the Boulder campus of the University of Colorado. It

went something like this:

“Do you know Fat Burns?”

“No.”

“Well, it does.”

Everafter, whenever we met, we

called each other “Fats.” And we’d chuckle quietly in recollection of a joke

neither one of us could remember very well. Three or four years ago, I sent him

an old novel I’d found in a used book store because the title was Red Pepper Burns. It was so close.

“Do you know Red Pepper Burns?”

“No.”

“Well, it does.”

When I ran across another copy of

the book, I bought it for myself.

I met Chris in about 1957. For the

next couple of years, we played follow the leader until he caught up with me

and passed me, surpassed me. An English major, he went into a career in

journalism; I, with a degree in journalism, didn’t.

A fraternity brother of his, Al

Shepard, brought us together. Al and I were trying to launch a new campus humor