|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 429a (June 29, 2022). We celebrate finishing our 23rd year with a roundup of recent editoons even as editooning is threatened, more mass murders enrage a nation, Florida governor vs Disney, reviews of Foul Play, Badass Broads, Davenport, Grass Kings, Lalo Alcaraz’s long journey, and Jack Chick’s ghost—and more, always much more. If you’re a non-$ubscribing visitor here, taking advantage (as we encourage you to) of our Open Access Month, you might consider wandering from the Rancid Raves posting at hand to look at some of the evergreen articles of history and biography in Harv’s Hindsight. Here are a few (look them up by date)—: Hubris & Chutzpah, the Al Capp/Ham Fisher Feud that Resulted in Fisher’s Death, January 29, 2013 Origin and Evolution of the “Comic Con,” November 30, 2017 Who Discovered Superman?, November 30, 2013 Unforgettable Jane (the British Comic Stripper), September 30, 2016 The Real Captain Easy, January-February, 2012 In order to assist you in wading through all this plethora, we’re listing Opus 429a's contents below so you can pick and choose which items you want to spend time on. An asterisk* marks the longest items. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order, beginning with the news of the day—:

MORE MASS MURDER —AGAIN AND AGAIN Bloody Month Editoons Spitzer Assault Weapons Are Machine Guns—and Machine Guns Are Illegal

THE SUPREME COURT HAS OFFICIALLY OVERTURNED ROE V. WADE NOUS R US EVENTS OF THE DAY CONTINUE TO THREATEN EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS * Editoonists Object to the New Catch-all Pulitzer Category AAEC Objects Past Winners Object NCS Objects Gannett Kills the Editorial Page Capitalists Not Journalists Run Newspapers Bookstore Being Sued for Selling Books Brewery Sued for Its Beer Label Chicano Cartoonist Alcaraz Wins Herblock Covering the New Yorker Clay Jones Wins RFK Award

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews Of—: The Newest Shaolin Cowboy Wolverine Patch Batman: The Knight The Closet

EDITOONERY Selection of the Month’s Editorial Cartoons —* Including DeSantis’ Fight with Disney

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

TODAY’S COLLEGE STUDENTS ARE INDIFFERENT TO LEARNING

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews—: * Foul Play! The Art and Artists of the Notorious 1950s EC Comics

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words—: The Delicious Russell Patterson Consider the Giraffe

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews,to Wit—: Bygone, Badass Broads

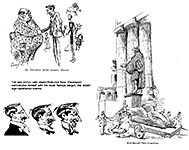

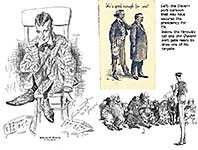

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets and Long Reviews—: * The Annotated The Dollar Or the Man? The Issue of Today

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status; Reviews Of—: * Grass Kings, Vol.1 and Vol.2

BADINAGE & BAGATELLES Lalo Alcaraz, La Cucaracha, the Herblock, and More —** The Long Journey of a Latino Political Cartoonist

PASSIN’ THROUGH * Fred Carter, the Cartoonist Behind Jack Chick

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND—

“If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: when you get to the $ubscriber/Associate Section (perusal of which is usually restricted to paid subscribers but this time, it’s all Open Access, kimo sabe), don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

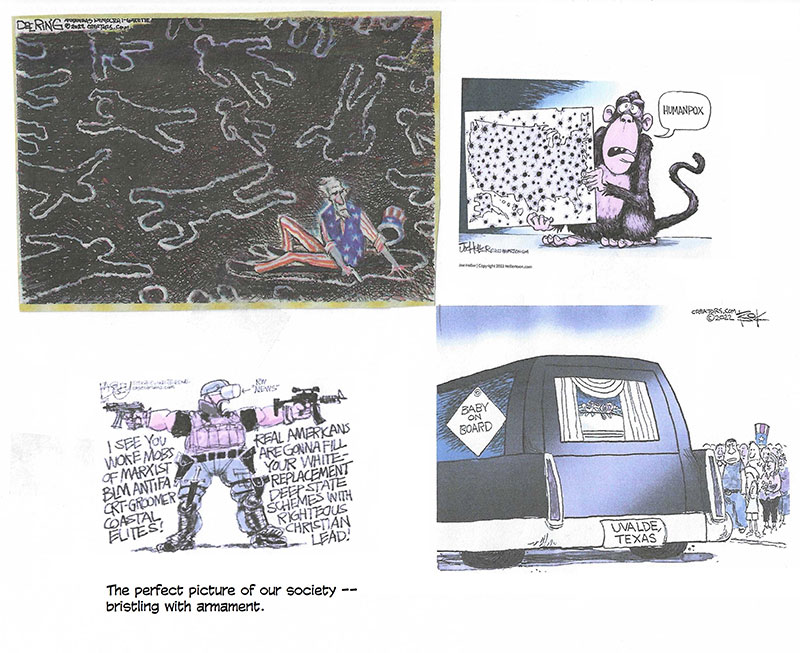

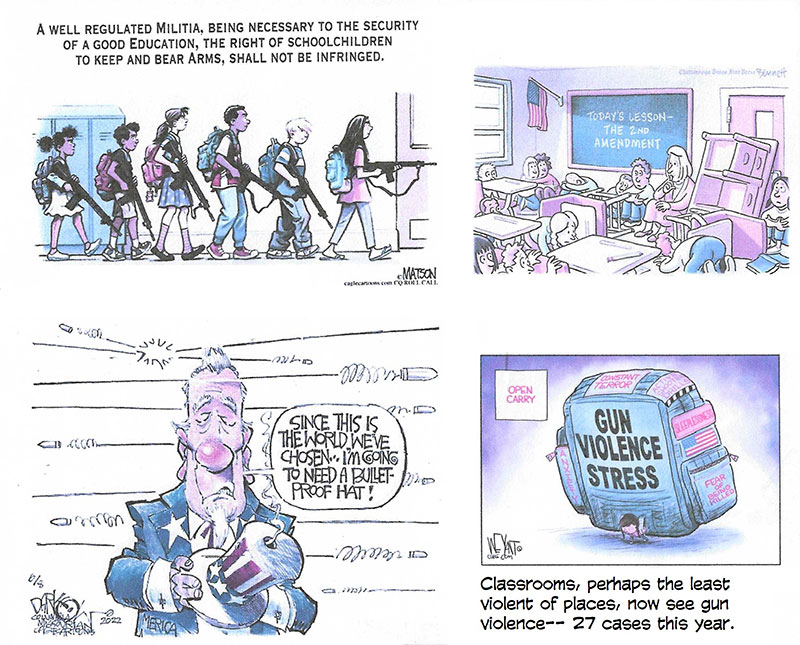

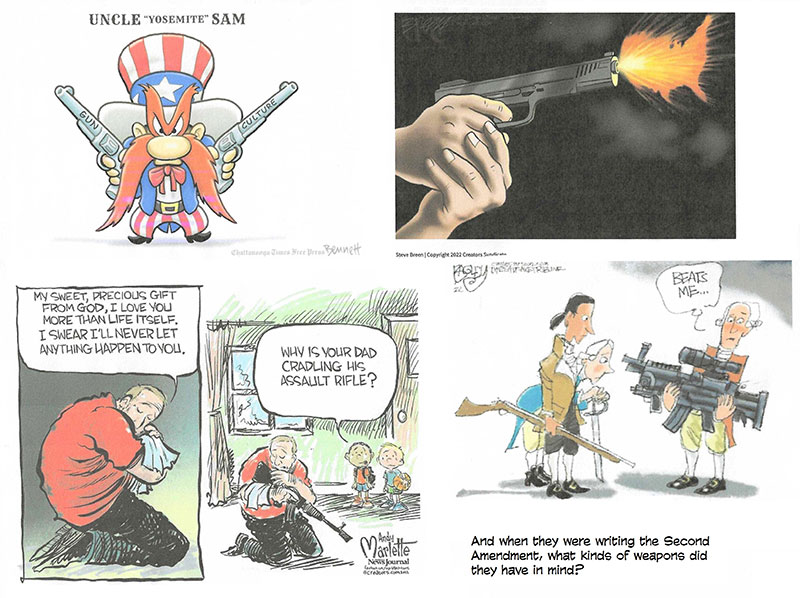

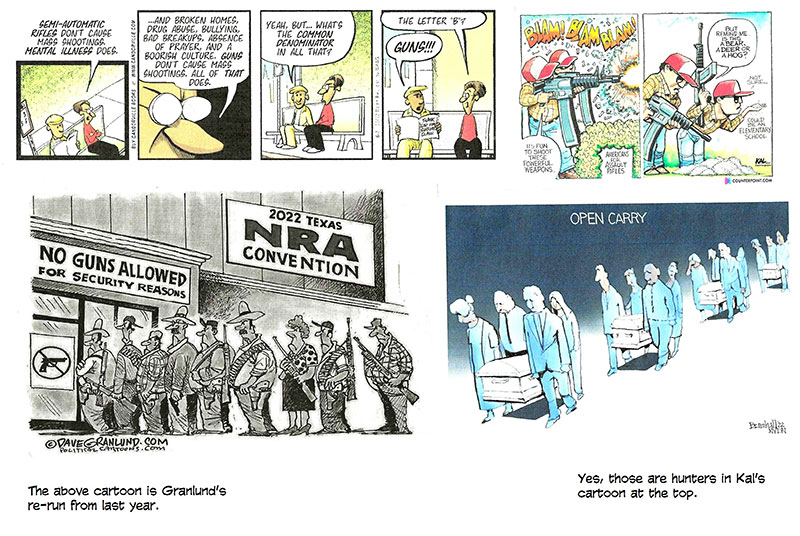

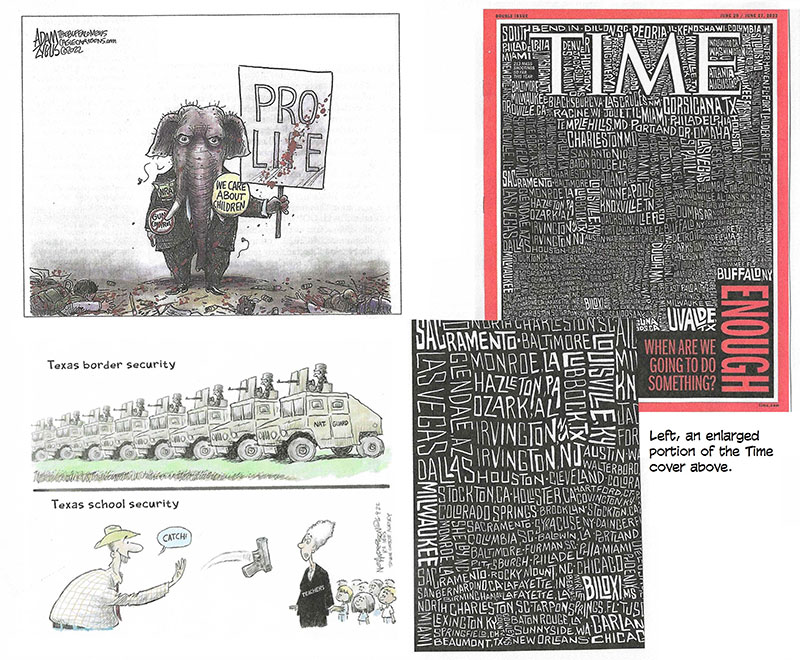

MORE MASS MURDER AGAIN AND AGAIN IT WAS ANOTHER BLOODY MONTH. The weekend of June 4-5 recorded 13 mass murders. Editorial cartoonists reacted predictably, as we can see hereabouts. Images of death and guns prevailed. Uncle Sam, chalking the outlines of dead bodies, a bullet-poxed national map, a baby in a hearse. Guns and killings in schoolrooms. Guns everywhere, Yosemite Sam with a vengeance—no longer a cartoon character. The terrible killing weapons of the 21st Century compared to the Second Amendmented rifles of the Revolutionary War. “Open carry” given a chilling translation.

Editoonist Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher adds the following text to his pictures of gigantic assault weapons in the hands of hunters: “New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Australia and Norway —all banned assault weapons after one mass shooting n their countries. This makes sense. These weapons are designed to kill a maximum amount of people very quickly. Any sane country would ban them. Take a hint, America.” But in this country, we still don’t ban guns: we make more of them. Annual domestic gun production increased from 3.9 million in 2000 to 11.3 million in 2020. There are about 400 million guns in the U.S. Our penultimate illo on this topic reproduces the Time magazine cover made up entirely of the names of places where this year’s 213 mass murders have taken place.

Said John Mavroudis, who created the cover: “In the time it took me to carefully write the words Uvalde, TX, that gunman extinguished so many beautiful lives. I could feel the sadness and fear and horror overwhelm me again.” Time’s editor-in-chief Edward Felsenthal added: “And just in the time it took that digital-first cover to go to print, the sadly unsurprising happened: those 213 shootings have already been joined by about three dozen more. “The bigger question, of course—far more important than what words we use—is what we as a society do. The gavel shape formed by the word enough on our cover is meant to signify the need for action. And that’s what the vast majority of Americans want. ... To try nothing in the face of routine massacre is unconscionable. As our cover asks, ‘When are we going to do something?’” Next to the Time cover, Adam Zyglis’s GOPachyderm holds a sign advocating for Pro Life, but blood spatters from gun violence have obscured the ‘f’ in ‘life,’ leaving only the ‘lie.’ Ain’t it the truth. Many states have passed laws making it easier to buy and carry concealed weapons. In 2011, only one state—Virginia—allowed “permitless carry”; but as of last month, The Week reported, 25 states do. Last year, 2,000 applicants were denied permits after background checks; now, all of them are free to carry concealed firearms. Meanwhile, just as we were going to post, the Supreme Court struck down a New York handgun-licensing law that required New Yorkers who want to carry a handgun in public to show a special need to defend themselves. So New Yorkers can carry at will. The 6-3 ruling, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, is the court’s first significant decision on gun rights in over a decade. In a far-reaching ruling, the court made clear that the Second Amendment’s guarantee of the right “to keep and bear arms” protects a broad right to carry a handgun outside the home for self-defense. Going forward, Thomas explained, courts should uphold gun restrictions only if there is a tradition of such regulation in U.S. history. Gun-control advocates say allowing unregulated carry of weapons (concealed or not) endangers police and the public, and there are statistics to back that up. One study found that gun homicides in Wisconsin rose by a third after a right-to-carry law was passed in 2011. In Missouri, gun homicides rose by 47 percent and gun suicides by 24 percent after the state repealed its licensing law. And yet a national Quinnipiac survey in 2019 found that 77 percent of Americans—including 68 percent of gun owners—back mandatory gun licensing. Ironically, we don’t need any new laws banning assault weapons. Our old laws do that just fine, thank you very much. They’re already on the books, as Robert Spitzer tells us—:

Guns Were Much More Strictly Regulated in the 1920s and 1930s than They Are Today By Robert J. Spitzer Distinguished Service Professor and Chair of the Political Science Department at SUNY Cortland. His most recent book is Guns Across America: Reconciling Gun Rules and Rights, published by Oxford University Press. THE FIRST SIGNIFICANT FEDERAL LAW AIMED at curtailing gun violence, the National Firearms Act of 1934, enacted a series of measures aimed mostly at stemming the spread of ever-more destructive weapons into the hands of criminals at a time of spiraling gangland violence. Chief among the weapons and accessories it regulated were sawed-off shotguns (defined as those having a barrel shorter than 18 inches), machine guns, and silencers. As if to punctuate the connection between the law and criminal violence, the NFA was signed into law on June 26. Bookending the signing was the killing of the notorious criminal duo Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow on May 23, and of uber-gangster John Dillinger on July 22. Yet the campaign to staunch the flow of such weapons into society began in the states the previous decade, when at least 27 states enacted measures to restrict or outlaw the sale and possession of fully automatic weapons prior to 1934— most especially submachine guns like the Tommy gun (dubbed “the gun that made the Twenties roar”). The first state to so act was West Virginia in 1925. ... Not only did states move to restrict fully automatic weapons— those that fire a continuous stream of bullets when the trigger is depressed— but also semi-automatic weapons that fire without reloading and with each pull of the trigger. At least seven, and as many as ten, states enacted legislation that in various ways sought to restrict such weapons. Sometimes, fully automatic and semi-automatic weapons were treated in the same way. For example, Rhode Island defined prohibited “machine guns” to include “any weapon which shoots automatically and any weapon which shoots more than twelve shots semi-automatically without reloading.” A 1927 Massachusetts laws defined prohibited weapons as, “any gun or small arm caliber designed for rapid fire and operated by a mechanism, or any gun which operates automatically after the first shot has been fire ... shall be deemed a machine gun.” Michigan’s 1927 law prohibited machine guns or any other firearm if they fired more than sixteen times without reloading. Minnesota’s 1933 law outlawed “any firearm capable of automatically reloading after each shot is fired, whether firing singly by separate trigger pressure or firing continuously by continuous trigger pressure.” ... As is true in much of life, changes in technology often drive changes in behavior. While the typical hunter of the 1930s might have used a bolt action rifle, today’s hunter is much more likely to rely on some kind of semi-automatic long barrel gun. Even if the hotly disputed category of “assault weapons” were banned nationwide today (as was true to a limited degree from 1994-2004), the vast majority of long guns owned and used for recreational purposes would still be legal. But what is notable, even astonishing, about the state laws just quoted is that they demonstrated little patience for semi-automatic firing married to the ability to fire multiple rounds without reloading. ****

By 1937, federal officials reported the sale of submachine guns in the U.S. had nearly ceased. In 1939, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the law constitutional. The law so effectively ended the spread and use of submachine guns that the federal government didn’t get around to actually banning civilian ownership until 1986. That’s right: assault weapons are banned in America. Machine guns are assault weapons.

****

What weapons are illegal in the US? Machine guns. Sawed-off shot guns. Explosives and bombs. Stilettos. Switchblades. Other illegal knives. Is 3-round burst illegal? A 3-round burst is legal only if you have the gun registered with the Feds as a fully automatic firearm. There is the binary firing system that the Feds have decided is legal. It shoots once on the trigger pull and once on the release of the trigger.

**** After the ban on automatic rifles was enacted in 1994, the number of mass murders and deaths by guns deceased; when the law expired in 2004 and selling and owning such weapons was legal again, the number of killings increased. What other proofs do we need as to what causes mass murder? AND, most significantly, we don’t need a new law prohibiting the sale and possession of automatic and semi-automatic assault weapons. With that 1989 law that bans machine guns, we have the law already on the books. Let’s enforce it.

******

Last Minute, Breaking News Just As We Tossed This Into the Web THE SUPREME COURT HAS OFFICIALLY OVERTURNED ROE V. WADE And Justice Thomas suggests several other hugely consequential rulings could be next. By Bredan Morrow at TheWeek.com; June 24, 2022 Justice Clarence Thomas joined the court's other conservative justices on Friday in eliminating the constitutional right to abortion in the United States. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the majority opinion, but Thomas also wrote his own concurring opinion, in which he argues the justices "should reconsider all of this court's substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell," adding that "we have a duty to 'correct the error' established in those precedents." In 1965, Griswold v. Connecticut established a constitutional right for married couples to access contraceptives, while the 2003 ruling Lawrence v. Texas said states may not ban sodomy, and 2015's Obergefell v. Hodges established the constitutional right for same-sex couples to marry. The Supreme Court in overturning Roe v. Wade undid nearly 50 years of precedent, also overturning Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which in 1992 upheld the constitutional right to abortion. Thomas in his opinion argued the court was correct in holding "that there is no constitutional right to abortion" and that "the purported right to abortion is not a form of 'liberty' protected by the Due Process Clause."

*******

Back up — what did the opinion say? The specific case before the court — Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization — pertained to a Mississippi law banning abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy, much earlier than the fetal viability threshold established by Roe. In siding with Mississippi on Friday, writes the Wall Street Journal, the court's six conservative members deemed the Roe decision to be "egregiously wrong" and "an error the court perpetuated in the decades since.” "We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled," the majority wrote in its opinion, referencing 1992's Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which was also struck down. "The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision … Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences." "It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people's elected representatives," they added. Dissenting Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Stephen Breyer just as potently rejected the majority's position. "With sorrow — for this court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection," the court's liberals wrote in their joint opinion: "We dissent." Is abortion now illegal everywhere? Not necessarily. In overruling Roe, the court has sent the issue of abortion back to the states, where its legality will be decided on an individual basis. Some states, like New York and California, have already codified the right to an abortion into law, and will be therefore largely unaffected by Friday's decision. But others, like South Dakota, Louisiana, and Kentucky, have laws that now immediately ban the procedure in Roe's absence. The same goes for Oklahoma and Texas. All make exceptions for the life of the mother. Elsewhere, in Idaho, Utah, North Dakota, Wyoming, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, these so-called "trigger bans" — laws designed to come into play should Roe disappear — will take effect after 30 days, and/or after a state official certifies the court's decision. But in states without trigger bans — like Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Ohio, and South Carolina — laws that forbid most or all abortions are likely to go into effect in the near future, the Washington Post notes. And in states like Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Virginia, the fate of reproductive rights "will depend on the upcoming midterms." *****

From USA Today: Today's decision does not mean abortion is illegal in all 50 states. But it does mean that people seeking abortion care will have to navigate a complex web of state laws that either protect or prohibit their right to choose. Across the South and parts of the Midwest, abortion is likely banned or more difficult to access. Meanwhile, North and Northwest states are poised to become havens where abortion rights are safeguarded. In 13 states, so-called trigger laws will go into effect following the Dobbs decision, immediately banning abortion in most instances with few exceptions for rape and incest, according to USA TODAY analysis. Some 16 states have codified the right to an abortion, and in 10 others, abortion rights have state constitutional protection. But even if abortion remains legal in a state, myriad restrictions constrain people's options and narrow their ability to get the procedure.

******

But the World Hasn’t Gone Completely Nutso Gene Popa on Carol Tilley’s Facebook: Do you know what brings me a glimmer of hope in the human species these days? Dmitry Muratov, a Russian journalist and Nobel Prize winner who disagrees with his country's invasion of Ukraine, put his Nobel up for auction in order to raise money to help shelter and feed Ukrainian refugees. He hoped to maybe get a couple of hundred thousand dollars ... and instead he raised $103.5 million! UNICEF now has the money, and they are putting it directly to work aiding refugees. So you see, we aren't all too damaged to do good. Thanks, Gene.

*******

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

EVENTS OF THE DAY CONTINUE TO THREATEN EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS

Editoonists Object to the New Catch-all Pulitzer Category The Pulitzer Board recently introduced a new category of achievement in journalism, Illustrated Reporting and Commentary. But by inventing a catch-all category that includes all kinds of illustrated journalism, they did away with the Editorial Cartooning category, subsuming it in the new catch-all category. And editoonists in the AAEC think that’s a mistake. We here at Rancid Raves agree. In an Open Letter to the Pulitzer Board dated in early May, AAEC explains better than we could—

The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists would like to congratulate illustrator Fahmida Azim and the other contributors to the team that created the illustrated article, “I Escaped a Chinese Internment Camp,” which won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in the recently renamed category of Illustrated Reporting and Commentary. We would like to also congratulate the finalists, The New Yorker cartoonist Zoe Si, and Washington Post editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes. Cartooning, regardless of genre, is time intensive, often challenging, occasionally dangerous, but always rewarding work. While we celebrate Azim, Si, and Telnaes, the AAEC once again encourages the Pulitzer Board to consider reinstating Editorial Cartooning as its own Pulitzer category, while also recognizing Illustrated Reporting as a separate form. Each is a different type of journalism, just as Commentary and Feature Writing are considered separate styles, and Breaking News and Feature Photography have separate Prizes. Editorial cartoons are quick, in-the-moment commentary, whose artists have to educate themselves on complex issues and craft well-informed opinions in a single take that emphasizes clarity under daily deadlines. Illustrated reporting, or comics journalism, takes days, weeks, or months to craft a story, which can run for pages, and which may or may not be presenting an opinion. By having two separate categories — one for Editorial Cartooning and one for Illustrated Reporting — the Pulitzers can celebrate what makes each genre unique, and recognize the growing field of graphic journalism without slighting the long history of political cartooning. The AAEC asks the Pulitzer Board to consider this proposal for the future. Signed, The Officers and Board of Directors of the AAEC

******* THEN the AAEC objection received an endorsement from dozens of past winners of the Pulitzer for Editorial Cartooning; to wit—:

Pulitzer Prize Cartoonists Pen Protest Letter to Pulitzer Board Ten days after the 2022 Pulitzer Prizes were announced, 33 cartoonists who have won or been finalists for the award in Editorial Cartooning signed an unprecedented open letter to the Pulitzer Board about recent changes to the Prize. After quietly expanding the parameters of the Editorial Cartoonist category in 2020 to include illustrators and graphic reporters, the Board that presides over the judging process for journalism’s biggest award renamed the category “Illustrated Reporting and Commentary” at the end of last year. This unannounced move came months after the Pulitzer Committee refused to pick a winner among the three qualified finalists in 2021, and 99 years after the “Editorial Cartooning” category was created. [See Opus 418a for June 2021for details.] Last week the AAEC sent a letter to the Pulitzer Board petitioning the restoration of the [Editorial Cartooning] award, and now almost three dozen recipients of the Prize are collectively seeking the same thing. Here is their letter (dated May 19) in its entirety.

Dear Pulitzer Prize Board— We are dismayed to see the Editorial Cartooning category removed from the annual conferring of Pulitzer Prizes. From America’s inception, the editorial cartoon has crystallized our messy political struggle. Iconic historic images — like Benjamin Franklin’s “Join or Die” woodcut, Thomas Nast’s plutocrat with a money bag head, and Herblock’s cartoon coining the term “McCarthyism” — all sprung from the minds of individual cartoonists drawing visceral, emotional, and urgent opinions, in response to the news events of their day. The greatest American editorial cartoons draw on every inch of the First Amendment to, as John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty, “push arguments to their logical limits.” For 100 years the distinguished Pulitzer Prize has walked hand-in-hand with the idiosyncratic editorial cartoonist, elevating the gritty public artform by (almost) annually bestowing its revered prize upon the “best” of the craft. This partnership has allowed publishers with intestinal fortitude to keep a seat for the local cartoonist on the newspaper editorial board, justifying their employment with the weight of the award. This has, without a doubt, nurtured the vitality of the medium and helped our nation weather its political discourse for the better. While the landscape of print journalism has changed, and far fewer practitioners of the [editorial cartoon] form are employees of newspapers, those newspapers still print scores of editorial cartoons every day. Added to that, there are now more editorial cartoonists than ever reaching their audiences directly via the digital screen. Our numbers are more stylistically, ethnically, and gender diverse. The conferring of a cartooning Pulitzer Prize continues to be a powerful affirmation of support, even more valuable for artists vying in today’s raucous public discourse. So, it is with alarm that we see the Editorial Cartoon prize morph into a nebulous award for “Visual Reporting and Commentary.” In journalism, reporting always emanated from a newsroom, and commentary from the very deliberately walled-off editorial opinion factory. This American tradition should not be watered down, and as we witness our country’s intensifying political divide, it feels like a dangerous moment to abandon us dagger-penned town criers. We fully understand the need to acknowledge and elevate important new forms of journalism, including powerful visual storytelling, like the ones you honored in 2022, 2018, and in 1992 when the Pulitzer Committee bestowed a Special Citation on Art Spiegelman’s Maus. But because these formats employ drawn visuals doesn’t mean they are the same as an editorial cartoon. Readers of the news have always treasured the quick and rude interlude offered by the ink-spattered rectangles nestled within the ocean of important words. And lest we forget, cartoonists draw our arguments using satire, a scarce commodity in journalism, but one that helps stick a message instantaneously and memorably in ways even the finest writing cannot. We mock the powerful, reduce tyrants to sniveling caricatures and twist demagogues’ own words against them. A serious illustrated reporting piece serves a notably different purpose. As grateful beneficiaries of the Pulitzer’s gravitas, we agree with the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists’ plea to restore the original Editorial Cartooning prize while also — as is done for multiple writing and photography categories — retaining the new prize created for Illustrated Reporting. In 1922, the first Pulitzer Prize for cartooning was awarded to Rollin Kirby for his “The March To Moscow” of 1921 In 2022, We the Cartoonists hope to continue our march with the Pulitzer Prizes still at our side, with categories honoring all, fittingly. Respectfully and sincerely, The signers include past Prize winners Matt Davies (who won in 2004), Clay Bennett (2002), Mike Luckovich (1995, 2006), Joel Pett (2000), Walt Handelsman (1997, 2007), Signe Wilkinson (1992), Mike Peters (1981), Michael Ramirez (1994, 2008), David Horsey (1999, 2003), Adam Zyglis (2015), Jack Ohman (2016), Jim Borgman (1991), Steve Sack (2013), Mike Keefe (2011), Darrin Bell (2019), Ann Telnaes (2001), Matt Wuerker (2012), Kevin Siers (2014), Nick Anderson (2005), Ben Sargent (1982), Steve Breen (1998, 2009), and Mark Fiore (2010), along with finalists Lalo Alcaraz, Marty Two Bulls Jr, Ruben Bolling, Ted Rall, Tom Tomorrow, Rob Rogers, Robert Ariail, Jeff Darcy, Steve Kelley, Chip Bok, and Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher. Since the letter was sent off, more Pulitzer winners and finalilsts have signed on to the protest, including 2020 winner Barry Blitt and Pat Bagley, the longest-employed staff editoonist at a daily newspaper.

******* AND THEN, the National Cartoonists Society jumped in, objecting to the Pulitzer Board dissolving the Editorial Cartooning category. Here’s that letter from the NCS Board of Directors—:

June 10, 2022 Since 1946, the National Cartoonists Society has existed to advance the ideals and standards of professional cartooning in its many forms. To this end, the NCS board of directors hopes you will consider the following request. As an organization representing cartoonists, we are deeply concerned about the decision to retire the “Editorial Cartooning” category for the Pulitzer prizes. We appreciate that the Pulitzers are expanding the types of cartooning and art that are award-worthy. We have done the same with our own awards. However, just as “News Photography” and “Feature Photography” are different, “Illustrated Reporting and Commentary” and “Editorial Cartooning” are two distinct genres of work and should be separate categories. We ask that the Pulitzer Board officially retain “Editorial Cartooning” as its own category in addition to recognizing the category of “Illustrated Reporting and Commentary.” The skillset of each form of cartooning is distinct: illustrated stories select a topic and are produced over an extended period of time, requiring a level of cohesion, research, and development unique to this craft. Editorial cartooning demands an immediate [daily] interpretation and reaction to events in real-time, necessitating an ongoing awareness of complex and often unpredictable contexts. At a time when news cycles are smaller and smaller, this skill has become even more crucial. Combining editorial cartooning and illustrated reportage together into one category does a disservice to both genres. To us, the situation is like having a sprinter and a long-distance runner competing for a single gold medal because they’re both track and field athletes. We do not want to undermine the importance and skill of graphic reporting, comics journalism, or long-form [illustrated] reportage, nor take anything away from that category’s deserving winners and nominees. Additionally, we are not suggesting that you remove the category of “Illustrated Reporting and Commentary”; rather, we ask that a category for “Illustrated Reporting and Commentary” exist alongside a separate category for “Editorial Cartooning.” We believe both skillsets deserve to be recognized. The NCS urges the Pulitzer board to adopt this change or consider opening the discussion with us to explore further. The Board of Directors National Cartoonists Society (Est 1946)

**********

GANNETT KILLS THE EDITORIAL PAGE And Stabs the Editorial Cartoon in the Front By Rick Edmonds, Poynter, June 8 Beginning in the spring and accelerating this month, Gannett is cutting back opinion pages in its 250-newspaper chain to a couple days a week, refocusing what opinion is still published to local rather than national issues. The change is evolutionary, Amalie Nash, senior vice president for local news and audience development, told me [Rick Edmonds] in an interview. Experimental approaches in the same vein at papers like The Tennessean and Milwaukee Journal Sentinel date back as far as five years. A series of reader surveys and a task force of editors have persuaded her and other executives to recommend a new chain-wide pattern as part of Gannett’s push to make digital content its focus. Among findings supporting a new approach, Nash said, were:

◘ Readers do not want to be lectured at or told what to think. ◘ Routine editorials, point-of-view syndicated columns and many commissioned guest essays consistently turn up as the most poorly read articles online. ◘ Readers can find a range of opinions on hot national issues on the internet — so replicating that sort of content locally is a waste of time, space and budget. ◘ In the digital space, readers may not easily distinguish opinion pieces from straight news reports. ◘ A more promising approach, as an April strategy document puts it, is “highlighting expert local voices that are not the same-old talking heads and political hacks.”

The new opinion program is a strong suggestion, Nash emphasized, but not an edict. Editors at individual properties are free to tailor the general principles to what they think best suits their community. [Still, cutting back editorial pages to once-a-week is the implied command. And the absence of an editorial page means, for most papers, no editorial cartoons, already gasping their last.] ... I received tips or complaints from a half-dozen retired editors, who see the changes as a veiled cost-cutting move and abdication of the principle that a newspaper needs to stand for something and say so regularly. ... More objections came from groups representing editorial cartoonists. At the Des Moines Register, opinion editor Lucas Grundmeier wrote: “Our emphasis will be on quality, not quantity, shifting to publication of a weekday opinion page on Thursdays only. Our current four-page Sunday section will continue.” And the remaining content will be local and even hyperlocal, he said, with a focus on solutions as well as identifying problems. Nash also offered, as an example, changes at the Columbus Dispatch, “which had a pretty traditional seven-day a week editorial page.” A new opinion and public engagement editor, Amelia Robinson, has flipped all that. She wrote in an introductory column in December that she sees her mission as “being able to provide platforms for the exchange of ideas … I see myself as a conversation facilitator.” ... Newsletters and video were being explored as adaptations for digital opinion journalism. Solutions journalism was finding its way as an alternative to the old ways, as David Haynes of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel renamed what was his opinion section “Ideas Lab.” ... Gannett’s April strategy summary, headlined Opinion Content Recommendations, describes them as “research-backed ideas for a smarter, sharper, more constructive discussion, with our local news brands at the center.” That, at any rate, is the giant chain’s pitch. Whether news customers will be buying is about to be tested in real time in (pardon the expression) the court of public opinion.

**********

NEWSPAPERS LOSING MONEY The Gannett maneuver is clearly inspired by financial considerations. Newspapers these days are owned by hedge funds and other investment entities, and they demand profits that can be shared with investors. Newspapers can generate profit in one (or both) of two ways: increase income or reduce expenses. Income can be increased in one (or both) of two ways: increase circulation (buying customers) and/or advertising. Neither is likely in the Internet Age. People get their news from the Web; and the greatest advertising source of income was classified ads, which the Internet has hijacked away from daily newspapers. In short, newspapers have lost both of their traditional was of generating income. The only remaining way to turn a profit, then, is to reduce cost. One of the ways newspapers do that is by reducing payroll/staff. Newsroom population of reporters has been drastically reduced in recent years. And the reduction continues. Cutting back editorial pages helps reduce cost even further. Much of the editorial content is supplied by syndicated columnists for the use of which papers pay a fee; thus, papers save money by reducing the number of columnists (which, in this case, is done by reducing the number of editorial pages per week). And another consequence of reducing the number of editorial pages is the practical elimination of editorial cartoonists. Staff positions will be gone, and fees for syndicated cartoons will be nearly eliminated outright. The over-all quality of daily journalism suffers. Fewer reporters, less news; ditto for the editorial page. Journalism is dying. But today's newspapers are not produced by journalists. They’re produced by capitalists. The "journalists" of yesteryear— starting with the owners of many newspapers— were motivated as much by a desire to wield power as by journalistic principles. Political power. Newspaper owners wanted to influence their communities. Today's owners aren't interested in community welfare or the power to alter community welfare. They're interested only in the bottom line. The pursuit of power inherent in newspaper ownership of yore had, as a by-product, good journalistic practices. That doesn’t mean newspapers were objective in reporting the news. They may have been—in this department or that, depending upon the owner’s interest—but at least they were fact-based. Newsstories about events in the community had to be fact-based: if they weren’t, readers would know, and they would lose confidence in the newspaper. The greater the confidence the reading public feels about its newspaper, the greater the influence the paper has in the community. Thus, the more fact-based reportage, the greater the circulation and, perforce, the owner’s civic power. But bottom-line newspapering isn’t interested in facts or community power. It is interested only in the bottom line. That’s newspapering today. And it’s been going on for too long, but is not likely to change.

BOOKSTORE BEING SUED FOR SELLING BOOKS By Kelly Jensen at bookriot.com Right-wing groups are pushing a narrative that suggests public schools are at the epicenter of a a carefully programmed indoctrination, forcing gender and sexuality onto young people starting in kindergarten. And reaction has gone beyond schools. In early May, a Virginia lawyer filed suit against the Barnes & Noble store in Virginia Beach. It started with the schools. Virginia Beach schools voted to remove Gender Queer from shelves after school board member Victoria Manning complained about it and several other books within the schools. Following an initial review of the book, Manning appealed the decision made to keep the book and after reconsideration, the book was pulled. Now Virginia Beach attorney and State Delegate Tim Anderson posted on Facebook that he and his client Tommy Altman— a right-wing Republicon running for Congress in the Virginia Beach district— have asked the Virginia Beach Circuit Court to find “probable cause that the books Gender Queer and A Court of Mist and Fury are obscene” and must not be available to “unrestricted viewing by minors.” “My client, Tommy Altman, has now directed my office to seek a restraining order against Barnes & Noble and Virginia Beach Schools to enjoin them from selling or loaning these books to minors without parent consent,” reads Anderson’s post. No longer is this about the rights of students to access books. It’s now about the rights of private businesses to sell books. Anderson suggests this is a new avenue for parents to fight. “We are in a major fight. Suits like this can be filed all over Virginia. There are dozens of books. Hundreds of schools,” he said. Plenty of material to fuel Altman’s political campaign. Responses to Anderson’s announcement from followers encouraged such action and suggest this is just the beginning. Several have mentioned fighting such fights against “obscene” materials for months, maintaining that children should not be exposed to such obscene books. Still more comments applaud this brave move and see it as a way forward in book banning outside Virginia. Barnes & Noble has yet to respond to the legal actions taken. As a private business, they are not only allowed to sell what they wish to sell, but they are under no obligation by anyone to move materials out of their facilities. But lawsuits like this further fuel misinformation campaigns by these groups. Anderson’s announcement is more than tacit approval of Altman’s run for Congress. Anderson has made books a big part of his social media strategy and has riled up his base through it. Though this lawsuit includes only two books, Manning, the school board member who triggered the removal of Gender Queer, has her sights on Saga by Brian Vaughan next. She has been at the forefront of book challenges in Virginia Beach since the school year began, challenging The Bluest Eye for being “too racy,” despite never having read the book.

NOBODY’S SAFE By Emily Mikkelsen, Nexstar Media Wire In

North Carolina, a Maryland-based brewery sued about its beer label. A court

ruled in favor of the Flying Dog Brewery, a craft brewery that filed a lawsuit

against the North Carolina Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission, calling its

regulation allowing the ban of labels commissioners feel are “undignified,

immodest or in bad taste” a violation of the First Amendment. The label, illustrated by artist Ralph Steadman, depicts a naked cartoon character standing by a fire. The NC ABC rejected the beer because commissioners thought its label was in “bad taste.” The agency later allowed the beer to be sold. In a news release, Flying Dog stated they believed that this was not only a case of “appointed bureaucrats trying to impose their views and preferences on others,” but the regulation was unconstitutional in general. “The First Amendment is the last defense against authoritarian and arbitrary government, and it must be protected against any and all threats,” said Jim Caruso, CEO of Flying Dog Brewery. “With the First Amendment seemingly under attack from all sides, it is heartening to see court decisions like this that protect the freedoms that it embodies.” Flying Dog is no stranger to lawsuits about their beer labels, having won similar lawsuits in Michigan and Colorado as well. A federal appeals court ruled in favor of the brewery in 2015 regarding a ban of the sale of its Raging Bitch beer in the state of Michigan, news outlets reported. The dispute began in 2009 when a board determined the label to be “detrimental to the health, safety, or welfare of the general public.” The label featured a drawing of a female dog with accentuated features, bared teeth and a tongue covered in blood.

CHICANO CARTOONIST ALCARAZ WINS HERBLOCK By Emily Leopard-Davis at Al Dio The Herblock Prize for excellence in editorial cartooning was awarded to Lalo Alcaraz for his work in 2021. Alcaraz is the first Latino to receive the Herblock Prize. The prize is named after Herbert Block, an editorial cartoonist from the Washington Post whose career spanned from World War II to the first year of George W. Bush’s presidency. Block won numerous Pulitzer Prizes during his career, including one for Public Service on the Watergate scandal. The Herblock Prize has been handed out annually since 2004, three years after Block’s death. Alcaraz

is a Mexican-American editorial cartoonist based in San Diego. His editoons

have appeared in many different publications, including Daily Kos and Al

Dia News. He is also the creator of La Cucaracha, a Latino-focused

daily syndicated comic strip and POCHO, a satirical website. La Cucaracha is the first political Latino comic strip to be nationally syndicated and has

been running since 2002. Alcaraz’s cartoons have been featured in galleries, publications, television, and documentaries. He has several books out, including Migra Mouse: Political Cartoons on Immigration and Latino USA: A Cartoon History, 15th Anniversary Edition. Alcaraz is currently the Visual Artist In Residence for the School of Transborder Studies at Arizona State University. Most recently, he has used his cartoons to combat vaccine hesitancy among Latinos, partnering with CovidLatino.org and the California Department of Public Health. One of his vaccine cartoons, Vacunao o Muerte (Vaccine or Death), was cited by the judges’ statement. The piece is a homage to the protest poster by Emanuel Martínez, Tierra o Muerte (Land or Death). For more about Alcaraz and his creations and productions, scroll down to Badinage & Bagatelles near the end of this posting where we go on at Great Length about Lalo and his work.

COVERING THE NEW YORKER The week’s news, which often inspires the cover art at The New Yorker, was too horrible for pictures. Nineteen children and two adults dead by a shooter’s hand Tuesday at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Tex. And yet, despite the emotional impact, Françoise Mouly, the magazine’s art editor, had to ask herself: could there be an artistic response that would capture how devastating America’s latest mass shooting is? “Fortunately, artists do try to channel their emotions and reach for the wordless forum of the cover” of The New Yorker, Mouly told Michael Cavna at the Washington Post. “Many sent sketched responses combining blackboards, empty classrooms, apples, flags, guns and bullet holes.”

When New Yorker editor David Remnick saw Drooker’s scrawled shapes, Mouly recounts, he knew: this is the one. The cover art, titled simply “Uvalde, May 24, 2022,” was chosen, Cavna says, “not only for its concept but also for the power of its rendering.” Said Mouly: “The rawness of the execution makes for a visceral image. The rough outlines catch something of the pain and rage we all feel — about the fact this would happen and would happen again and again.”

CLAY JONES WINS RFK Editoonist Clay Jones was presented with the 2022 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Cartoon Award on May 24 for efforts created in 2021. Said the RFK organization on recognizing Jones: “Cartoonist Clay Jones deftly and courageously covers the themes of human rights and racial equality throughout his work. His uniquely energetic style makes him a standout.” [“Uniquely energetic style” is one way of saying “manic madness and stunningly, energetically, antic” artwork. Jones reminds me that “cartoon” once referred to crazy looking objects and objets d’art. Any time you want to remember the good stuff, pause to ponder a Clay Jones cartoon, which puts the frantic in antic and makes us all smile: even if the topic is dead serious, the pictures can’t help but make us grin in joyful relaxation.] Founded by the reporters who covered Robert F. Kennedy’s historic 1968 presidential campaign, the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards honor outstanding reporting on issues that reflect Robert Kennedy’s concerns, including human rights, social justice, and the power of individual action in the United States and around the world. In accepting the RFK, Jones went on at some length, as follows—: I promised a few friends and cartooning colleagues I would get around to creating a post of my RFK award-winning entry. I still feel weird saying that. Each editorial cartoon contest requires a certain number of cartoons in an entree. The Pulitzer, Herblock, and RFK each require 15 cartoons. All the rest require less. It's extremely difficult to select 15, or fewer, of your best from over 300 cartoons [produced in a year]. And the RFK is special. While most of the other contests want your best, the RFK wants your best on a specific subject, human rights. I love that about this organization as human rights is my main focus. Some of these cartoons got me suspended on various social media platforms. Then Jones posted the cartoons he submitted to the contest; and we post them near here, all 15 of them.

Jones continued: I can't thank the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization enough. I'm now on the list with the likes of Don Wright, Mike Peters, Paul Conrad, Clay Bennett, Mike Luckovich, Matt Davies, Doug Marlette, Signe Wilkinson, Dan Perkins, Jen Sorenson, Mark Fiore, Jack Ohman, Davi Horsey, Darrin Bell, Mike Thompson, Stephanie McMillan, J.D. Crowe (last year's winner), and Herblock. Whoa. I came into this business looking up to these people. I still do. I was told the name of a couple of cartoonists who were in the running with me this year and they're also people I greatly admire. So again, whoa. This award means the world to me. It only took me 32 years to win a national award. I also want to thank everyone who's ever supported me for helping me get here. From colleagues in Mississippi, Honolulu, Virginia, and other locations who've commissioned cartoons from me, to CNN, to everyone at GoComics, to all my newspaper clients, to people who comment, like, and share on social media, to everyone who's contributed financially, bought a print, or a book, to everyone who views and comments here, to the family members who still talk to me (even my older MAGA sister who told me I "wasted my talent"), and even to those who've criticized, thank you. I hope you know how much your support has meant to me. It's so rewarding knowing my insane crazy style of weirdness has finally been validated. You rock.

ODDS & ADDENDA

☻ Funny Times, a monthly cartoon tabloid newspaper, has been in business for 37 years, its most recent issue tells me. The cartoon content is mostly gag cartoons (sample posted nearby) with a few editoons thrown in. The rest of every issue is newspaper columns by humorists. Subscriptions at FunnyTimes.com start at $28 for 1 year (“Best Value” $68 for 3 years).

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled \into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Awe. The feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world. Awe stops us in our tracks. It makes us confront our smallness and puts us in our place. It expands our frame of reference. And it helps us look outside of ourselves.—Karen Einisman, quoting Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt

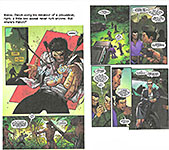

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

JEFF DARROW’S SHAOLIN COWBOY is back for another series, Nos.1 to 7. This is the hero, you’ll remember, of Chinese or other Oriental origins who seldom speaks but spends whole issues fighting and, eventually, overcoming the odds against him in fisticuffs. In the first issue of this new series, the opening pages are given over to a vaguely bellicose conversation between two lizards, a father and his son (whom the father wishes to devour). Then one of the lizards spots the Cowboy off in the distance, walking through the desert in cowboy hat and umbrella, and decides to attack. He does so. For the second fight of this issue, the Cowboy uses the blanket he has draped around his shoulders as a weapon: you’ll recognize the towel-snapping the Cowboy does with it in the playful hostility that usually infects the traditional locker-room hostility, but here, the snapping is part of a life-threatening battle between the Cowboy and another prehistoric beastie, this one of the flying sort—a rhamphorhynchus.

Through it all, the Cowboy hangs steadfastly onto his parasol. The Cowboy is not a particularly likable person. But that may be the story’s fault: we see him only fighting, not much opportunity for character development. But in both the episodes of this issue, he demonstrates resourcefulness, an admirable trait if not a friendly one. This would be boring stuff were it not for the detail with which Darrow infects his renderings. Watching the drawings is the most rewarding of the pleasures this title affords.

WOLVERINE

IS BACK AS PATCH, a guise involving a patch over his left eye from whence he

derives his name. In Larry Hama’s story as drawn by Andrea Di Vito and Le Beau Underwood, he’s now living incognito in Madripoor. I’m looking

at No.2 in the series and I can’t remember why he’s incognito, but I’m not sure

No.1 ever told us. In the issue at hand, we witness Patch being assaulted by

various thuggish elements—with arrows that turn Thanks to his “healing factor,” Patch is able to survive all these assaults. Meanwhile, a line-up of hostile adversaries plot their own activities—the Yakuza, the Russians, bow-wielding native tribes, KGB agent Tatiana Nemikova, snobby General Coy, the tattooed men, and Nick Fury shows up with an eye-patch of his own. Obviously, I am unable to make any sense of these fragments being thrown at us every other page or so. But I like the whole notion of Wolverine wearing an eye-patch and calling himself Patch. He did this in an independent series some years ago, and I liked it a lot. So I have hope.

BATMAN: THE KNIGHT No.1 is yet another in the seemingly endless re-tellings of the Caped Crusader’s origin story: teenage Bruce Wayne witnessing the murder of his parents and, subsequently—much later—resolving to combat crime as a costumed avenger. It seems that everyone who has ever thought about doing a Batman story has his/her highly eccentric “take” on this worn-out fable. So now Chip Zdarsky has his turn. Zdarsky

adds a tiny wrinkle here, a little twist there, but it’s still the same story.

But this time, we must endure Bruce being treated by Hugo Sessions with Strange alternate with Bruce’s “adventures” developing his combat skills and other things. These episodes reveal him to be stubborn to a fault: he’s set on becoming a cop, and nothing will dissuade him from this goal. If the story is thematically repetitious, Carmine di Giandomenico’s artwork is stunning in its detail and impressive in narrative breakdown. And Ivan Plascencia’s coloring is superb. Anytime I felt myself falling asleep, the visuals quickly revived me.

TO ESCAPE FOR A MOMENT from the universe of superheroes, I picked up the first issue of The Closet, written by James Tynion IV and drawn by Gavin Fullerton. The opening sequence takes place in a bar, and we watch as a customer regales the bartender with his tale of woes—he and his family are leaving town, and his son Jamie has irrational fears of a monster in the closet. When the guy gets home, his wife berates him because he has misinterpreted what she asked him to buy and bring home, and after that row, his son wants to sleep with him where he’ll feel safe from the monster in the closet. But that’s not to be.

The story succeeds because of Fullerton’s artwork. In the monotony of the bar sequence where the setting and the characters’ placement in it is unchanging, Fullerton varies camera angle and distance to inject visual variety and, hence, some excitement into the proceedings. And that’s fine. And in the sequence with Jamie in his darkened room, seeing a monster, Fullerton’s art carries the whole show. It’s dark and gloomy, and the panels are narrowly focused on what Jamie is experiencing, so we get into his head. Nicely done.

QUOTES & MOTS Always wondered what the rest of this verse was; here ’tis—: But as Froggy was crossing a silvery brook, Heigho, says Rowley! A lily-white Duck came and gobbled him up, With a rowley-powley, gammon and spinach, Heigho, says Anthony Rowley! “Gammon and spinach”—what a great finish!

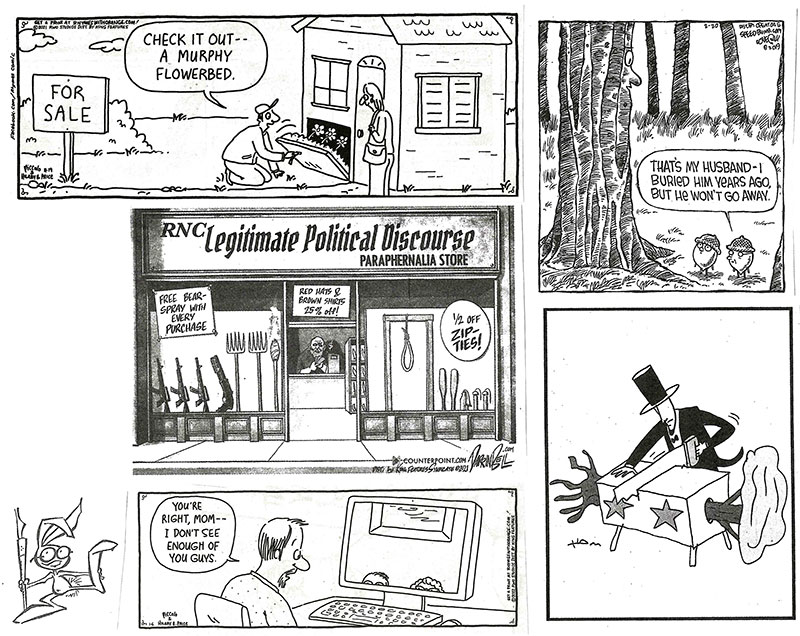

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy OUR FUNCTION IN THIS DEPARTMENT is to draw attention to the imagery that editoonists deploy to express opinions about current events. One of those “events” involves the right of a woman to determine how her body should function (or not) which seems about to end, if the leaked Justice Alito memo is to be believed. With the overturning of Roe v Wade on June 24, we learned how accurate Alito’s memo was. But we’ll focus here on the weeks before the Supremes’ decision was announced, when editoonists were responding to Alito. According to the imagery of editoonist Ratt at the upper left in our first array of cartoons, the right guaranteed by Roe is slowly crumbling away—leaving nothing behind but “woe.” Nice word play. Going counterclockwise (counter, that is, to our usual practice), we see in Mike Luckovich’s cartoon a glimpse of that “woe”—the difficulty in finding an abortion clinic in a state somewhere near your own.

Then at the right, Pat Bagley offers a sarcastic vision of Supreme Court justices who, during their confirmation hearings, said Roe was “settled law” but who, when on the bench and faced with a case requiring a decision, decided to scrap this “settled law.” Clearly, the wanna-be justices were fibbing in order to get confirmed. What kind of justice are they likely to promote? Dave Whamond at the upper right shifts our attention slightly to the population most affected by scrapping Roe. In two panels, he reveals the cynicism of red-capped MAGA women who want the right to own guns but don’t care that other people are determining what happens to their unborn children. The illogic inherent in this situation is confounding: protecting the right to life of the unborn seems contradictory to protecting the right to own and operate death-dealing assault weapons. In our next visual aid, we begin at the upper left with Joe Heller’s happy imagery dramatizing the inspirational effect upon young Black girls of the appointment to the Supreme Court of a Black woman, Ketanji Brown-Jackson. Next around the clock (back to our customary rhetoric) is Pat Bagley’s image showing the kind of war crime Putin is inflicting upon the Ukrainians. Children are dying by the hundreds as he bombs schools, hospitals, apartments and other places where large groups of people can be killed. And they are all civilians; according to the rules by which warfare is supposed to be conducted, civilians are not to be targets.

Rob Rogers also focuses on the Ukraine War. In his comic strip, each panel shows a reasonable reaction to the destruction being inflicted by the Russians. But in the last panel, Rogers attacks NATO for ignoring the death and destruction because Ukraine is not a member of the alliance. This is a bureaucratic not a humane response to the situation. Then Jimmy Margulies’s image tells us why we (NATO? USA?) should become involved in the Ukraine situation: that country is likely just the first target for the guns of Putin’s tanks as he seeks to revive the Russian empire by “taking back” independent countries that were once part of Russia. Next, he’ll try to take, say, Lithuania or Latvia or ...? In our next array, editoonists consider the consequences of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Michael Ramirez starts us off with a horrific picture of Mariupol in total ruin. The Russian invader says they’ve “saved Mariupol from Ukraine,” but there is absolutely nothing left of Mariupol. Russia’s current strategy is to bomb successive Ukrainian towns and villages into rubble, which raises a provocative question: if Russia should win this war by bombing Ukraine into oblivion, what’s the point? What has Russia gained? Just real estate of rubble. And what use is that?

Next, Pat Bagley’s image shows the Russian invader up to his wrists in Ukraine. Clearly Russia is in over its head—or, at the least, is in a predicament it hadn’t anticipated. Then Bill Bramhall keeps score with a picture of Death addressing Putin while they both ignore the corpses littering the landscape in their wake. And then Rob Rogers offers a chilling picture of the consequences of ignoring a war criminal for decades: Rogers has pictured the Ukrainian civilians who, according to report, have been killed by the Russians, who first, before shooting them in the head, bind their wrists behind their backs (presumably to prevent resistance to murder). In our next collection of images, Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins) takes us into This Moderm World where nonsense prevails (but looks an awful lot like today’s reality, which is its satiric point). Although seeming to take comic strip form, it actually isn’t: the panels are not instances in a succession of related instances. Each panel here is virtually a stand-alone example of idiotic comment by which Perkins exposes actual idiocy. In a comic strip, the panels are related to one another, each leading to the next until arriving at the climax.

Below at the lower left, Wiley Miller’s comic strip Non Sequitur shows how contemporary events have infiltrated the fictional world of the funnies, an allusion to Will Smith’s now infamous slap at the Oscars. At the upper right, Phil Hands shows the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm playing with a chess piece while its supporters clamor behind it; the real pawns in the game, however, are school children, if we are to judge from the image of the pawn in the Pachyderm’s hand. Suspecting that we need a break from such heavy-duty thinking, I’ve included Bill Schorr’s deliberately sexist giggle at the lower right.

WE’RE BACK IN THE CLASSROOM for the next visual aid, beginning with Rick McKee’s exploration of the idea of arming classroom teachers as a way of preventing mass killings at schools. McKee translates the situation into something silly, but as a former classroom teacher myself, let me say nothing could be less workable than arming teachers: generally speaking, nothing in teacher training or personality suggests these people would be comfortable or even mildly competent handling guns.

Next, Daryl Cagle’s imagery connects the speech balloon’s remark to schools; otherwise, the verbal content is its own satirical comment. Then Adam Zyglis puts us back in the classroom with today’s lesson scrawled on the blackboard, but the shell casings on the floor reveal what kind of past he’s talking about, and repeated classroom killing shows how little we’re learning from our history. And then Christopher Weyant uses two panels to ridicule the Republicons for their preoccupation with such minor matters as CRT and sexual orientation classes when faced with the dire consequences of school shootings. At the upper left of our next display, Drew Sheneman shows the kind of weapons people were talking about when they wrote the Second Amendment.

Next around the clock, Rob Rogers reminds us how long it’s been since we’ve urgently demanded laws needed to control access to firearms. To his caricature of Lyndon Johnson, Rogers adds: “President Biden is not the first president to demand action on firearms in the wake of a tragic massacre, and, sadly, he won’t be the last. Until we find the energy and fortitude to vote out the gun-loving NRA-owned Republicans in Congress, the bloody cycle will continue.” Then Matt Davies suggests we’ve arrived at a “tipping point”—a term usually indicating a change is about to take place. But as his image reveals, that’s not the tipping he has in mind: instead, it’s the money the NRA contributes to politicians. And, no—change is not about to happen. Finally, Guy Parsons offers a little drama that enacts our reluctance to learn from factual evidence all around us. Nation’s that have fewer guns in circulation have fewer deaths by guns. Duh. The idiocy is perpetuated in Gary Markstein’s image in the next array: the NRA and the GOP offer “thoughts and prayers” in the wake of the last mass murder, but they’re also the proprietors of the Guns R Us store, which urges more gun sales and less control.

In a gun culture like ours, as Bill Bramhall demonstrates in the next editoon, everyone is in favor of encouraging more guns. Then Gary Varvel shows why we’ve made such little progress: our political parties can’t agree on the problem, let alone the remedy. Next, Dave Fitzsimmons creates an image that includes comment on a number of issues: that’s the Trumpet, of course, and he carries around his supply of NRA donations while announcing how irrelevant are his actions after a shooting. And now, it’s definitely time for another break—this time, a longer one—from our grim preoccupation with serious political and societal issues. Here goes—:

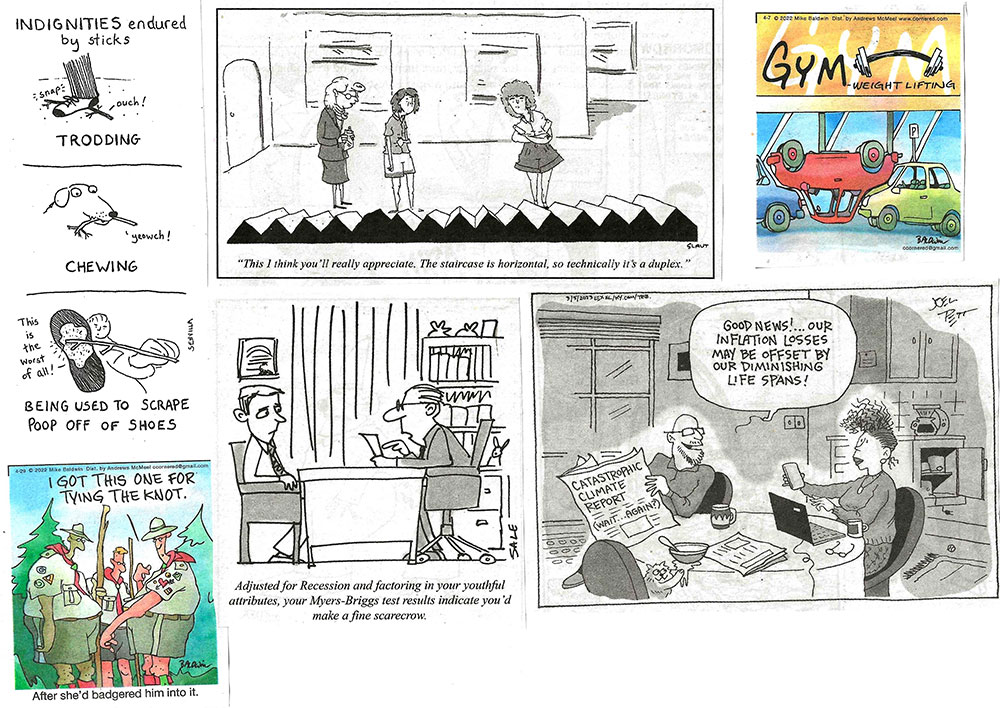

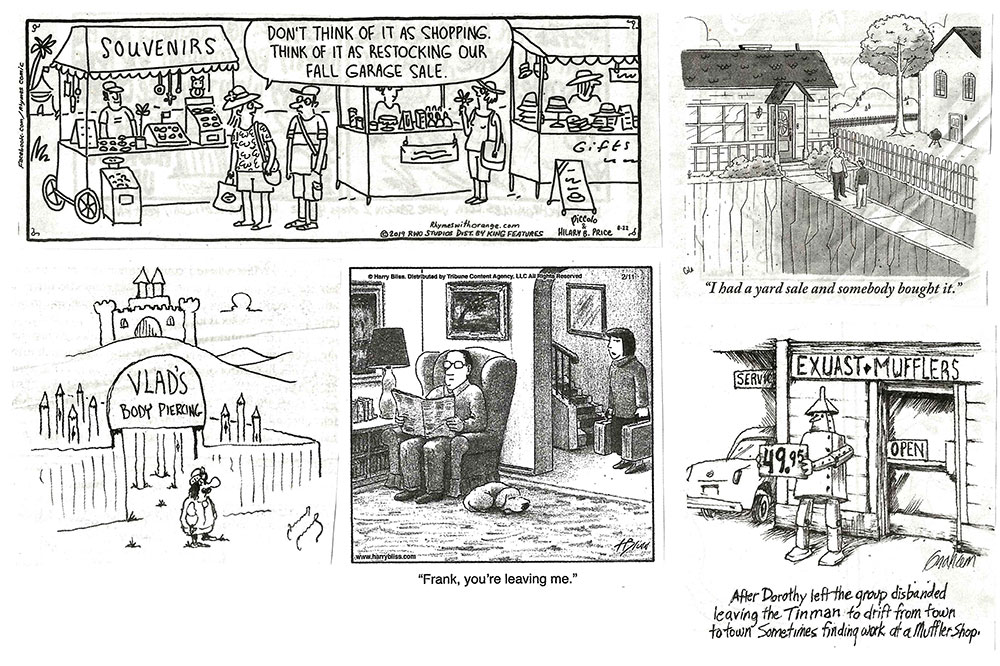

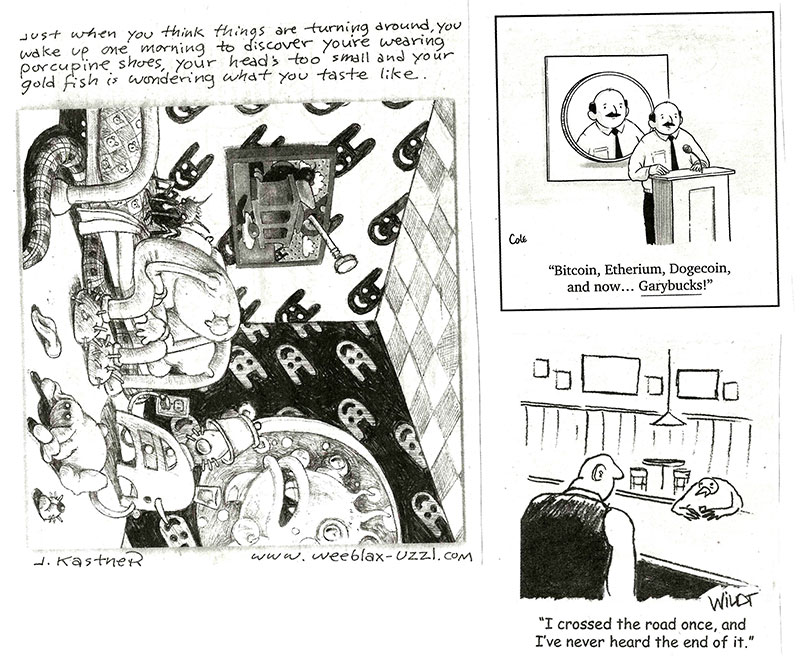

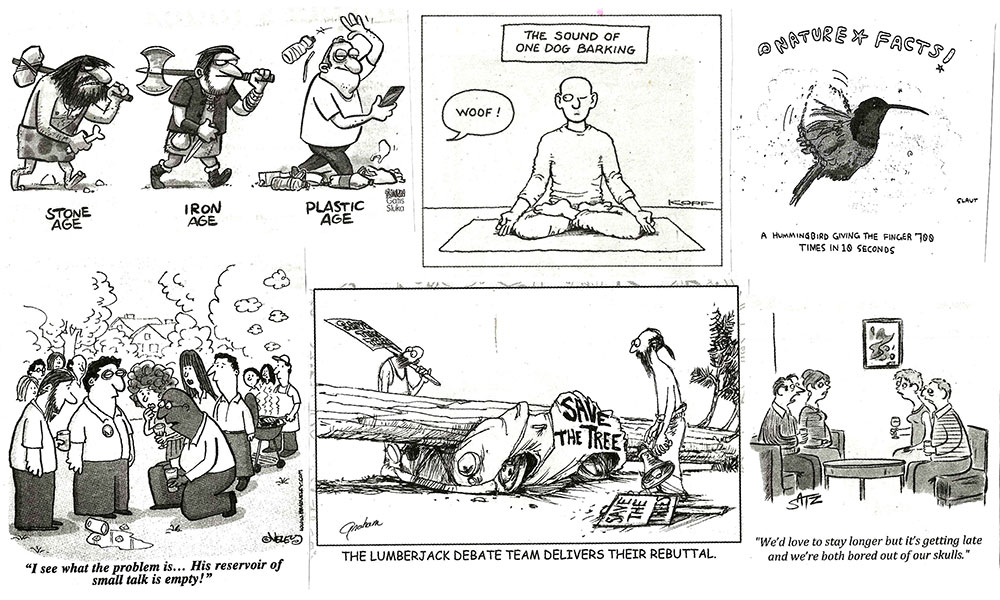

GAG CARTOONS (to deploy the technical in-house term for them) are supposed to be just funny. No political agenda for a gag cartoon. Well, usually. But sometimes a little social commentary edges its way into a fun-loving gag cartoon, and—suddenly—the cartoon acquires satirical heft and social import. And that’s true here, among the ’toons selected for viewing during this break.

Gag cartoons with political content are not inferior to ordinary fun-filled gag cartoons. They’re all equal as long as they provoke laughter or a gentle smile. Okay: enough fooling around. Back to the serious stuff.

WE COME AT LAST to Florida governor Ron DeSantis, who has supplied editoonists with material for months. He began by criticizing schools for teaching all that “woke” stuff—actual history of the U.S., for instance, particularly the white population’s role in perpetuating racism by building it into all our institutions (i.e., “critical race theory,” CRT)— which is what Pat Byrnes’ image ridicules at the upper left of our next array. In Byrnes’ image of DeSantis as school teacher, DeSantis displays an astonishing opposition to teaching about equality (of the races, presumably).

He’s holding a math book, reminding us that in Florida, according to one recent report, 54 of 132 math books failed Florida’s unwoke test (almost half, 41%). Racial prejudice and emotional learning are just two of the many "prohibited topics" cited as "impermissible" by the Florida Department of Education (FLDOE), which offered four examples of how teaching math “indoctrinates” students. In one example, if a textbook mentions “racial prejudice”—without saying whether it’s good or bad—then it’s indoctrination. Just mentioning it. DeSantis began his tirade against common sense by re-opening schools and beaches and other public places, thereby defying various health care regulatory bodies that had instituted mandatory mask-wearing and other restrictions. Then he signed a law—Parental Rights in Education, dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law— that uses “vague but menacing language” to ban any classroom instruction about “sexual orientation or gender identity” in kindergarten through third grade, thereby tapping into ignorant fears that teaching about sexual orientation and the like is indoctrination and promptly converts kids into being gay or transgender. Fox News host Laura Ingraham reacted by saying that public schools have become “essentially grooming centers for gender-identity radicals.” To which Michelle Goldberg at the New York Times responded: that’s right—the QAnon conspiracy theory that Democrats are “a cabal of pedophiles has gone mainstream.” DeSantis will have none of it. But it’s not clear what he can do about it short of railing at his presumed opponents. And an unsigned editoonist creates a comic strip at the right which seems to get into DeSantis’ head about all such issues, showing him to be a compulsive whiner. Then at the lower left, Nick Anderson sums up DeSantis’ achievement in making Florida “the most embarrassing state in the union.” Then Disney got into it. Disney, which has supported LGBTQ employees and causes, denounced the “Don’t Say Gay” law. And the company is nothing to sneeze at in Florida. With its massive theme park in Orlando, Disney World, Disney is the state’s largest employer with about 80,000 workers, and it brings billions in revenues to the state. The company announced it would suspend all political donations in Florida. DeSantis, however, was not to be intimidated. He signed legislation stripping Disney World of a special agreement that gave the company certain tax exempt status with the creation of the so-called the Reedy Creek Improvement District that enabled the company to build Disney World. Without Reedy Creek, there might not be a Disney World near Orlando, Florida. Alas, DeSantis’ revenge upon Disney was not without a certain backlash: DeSantis and his Republicon backers apparently did not calculate how disastrous revoking Disney’s special status might be for Florida taxpayers. Under its special arrangement, Disney heavily taxed itself, in effect, through Reedy Creek, funding upkeep for the roads, sewers, security, firefighting and other public services needed for Disney World. If Disney’s special status is revoked, Florida taxpayers will have to come up with the $163 million Reedy Creek has been collecting each year for those services. DeSantis claimed that wouldn’t happen, but it’s by no means clear to me or any of the rest of our Rancid Ravers. But when Disney took on DeSantis, editoonists chortled in delight: now they had an excuse to draw Mickey Mouse, making him the imagery of the company in its spat with DeSantis. In our next visual aid, Andy Marlette gets us started by employing other Disney characters, Winnie the Pooh and Piglet, to represent DeSantis’ effort to rid Florida classrooms of anything remotely resembling sex education. After that, the images are all Mickey.

Dick Wright shows what happens when Mickey sticks his finger in the electric socket of politics. Then Clay Bennett’s grinning cat represents the quarrel with DeSantis, showing it chewing on Mickey. After that, Adam Zyglis’ Mickey is just the mouse that the elephant is frightened of—the mouse with a sign proclaiming LGBTQ rights. On the next array, DeSantis’ ability to get himself on magazine covers and otherwise in the public eye is too great an opportunity for me to pass up so I’ve clipped and pasted. (The more visible DeSantis becomes, the more valid his hope to run for Prez.) And Tom Stiglich draws a perfect Mickey—this time, trapped in a perfectly rendered mouse trap.

Then Ruben Bolling finishes off this segment using a parody of Peanuts (“Q-nuts,” ‘q’ being the letter after ‘p’) to systematically ridicule the “Don’t Say Gay” law, culminating with an appearance in the strip of the world’s most famous cartoon character.

After that, we need another gag cartoon break.

THE ARTWORK carries a heavier load in a gag cartoon than it does in, say, a comic strip. Or so it seems to me. If you can’t determine pretty fast what the picture is about, then the caption that’s supposed to make sense (or poetry) of it won’t work. Take for example Vlad’s Body Piercing at the lower left of the first of our assemblages near here. What are those pointy things enclosed behind Vlad’s fence? Rockets? Spears? Because I’m baffled by what they are, I lose the rhetorical momentum: puzzling, baffled, I’ve forgotten what the joke’s about, and it’s lost.

And is Frank’s wife carrying Frank’s luggage? Or her own? On the next page, we begin with J. Kastner’s giant picture. Sometimes a gag cartoon is just a humorous drawing. That’s what this is. But in true cartoon fashion, the humor is lost without the caption that runs across the top. And in the Garybucks gag, that’s not a picture of a Garybuck behind Gary is it? It’s too big for that. So the joke here turns on Gary’s egocentricism. And below that—okay, it’s a bird at the bar, maybe, after reading the caption, it’s a chicken, but that derives from the caption, not the picture. Enough. Back to work.

A ROW OF PICTURES suggests, at first glance, some sort of progression: we’re intended to go across the row to a conclusion. And that’s what we do with Dave Whamond’s comic strip at the beginning of our next display. We progress through a short series of negative pronouncements until we reach the conclusion, which reveals with an image of prehistoric man in the background, just how retrograde the GOPachyderm’s ideas are. The Republicons want to live in the past.

Tom Tomorrow offers a progression, too. This Modern World often does not, but this time, it does: the last panel is, indeed, a “conclusion,” the outcome, to which the others have been leading, progressing, from one absurdity to the next, each one more idiotic than those that come before. Pat Bagley’s progression at the lower left is but a series of pronouncements, and the last one is a conclusion to which the words have been leading; the pictures add little except to identify the speaker as a Republicon. Switching back to the lower right, Steve Benson’s message is all picture. The Republicon elephant’s tusks seem, at second glance, to be Ku Klux Klan hoods. Yes, Steve doesn’t like the GOP much: he sees the Grand Old Party as a collection of bigots. Tom Stiglich musters a quiet homage to the soldiers in our history at the upper left of our next visual aid. Then Walt Handelsman finds an appropriate image that makes the connection between Biden’s releasing some of the Strategic Oil Reserve in the midst of spiraling gas prices and his hopes for improvement in his standing in the polls.

And Nick Anderson’s imagery portrays the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm as determinedly so anti-Biden that it can’t see any kind of big fish except the kind that threatens life and limb. Yes, it’s clear that Biden can do nothing right: everything he does is wrong. He’s condemned by the news media as well as the GOP. His reputation, his achievement, is so deliberately overlooked as to be essentially and entirely negative. I don’t see it that way, but I’m sure that’s a factor of my liberal leaning that blinds me to his shortcomings. At the lower left, John Darkow’s image of Elon Musk’s taking over Twitter is not likely to inspire confidence: Musk claims he’ll promote free speech, but so far, all we see is a lot of birds fluttering in hopeful anticipation. Dave Granlund begins our next array with an image about the economy: it seems that in our current state, we cannot afford to leave home for a vacation.

Next around the clock, Matt Wuerker’s imagery strenuously suggests that the judge that threw out the mask mandate for airplanes and public transport isn’t qualified to make that judgement: the image is of a crowd of people (scientists) opposing a single individual, the judge, who has dumped health guidelines and ignores the assembled expertise of the scientific community. Then Drew Sheneman uses two panels to question the extent of the Pachyderm’s dedication to the cause of Freedom: the elephant frees all of us from the mask mandate but will not free women from the obligation to give birth if pregnant. Kevin Siers also deploys two panels but to different purpose: he shows how the Republicon Party has been taken over by the Trumpet whose well-known silhouette signals that the brain in the Republicon head has been replaced by Trumpism. Trump is again the target as we begin our next display. Rick McKee shows the Trumpet mooning the statue of Justice, an image of contempt that confirms the headline in the newspaper box.

And Bill Bramhall’s image of Trump again has him exposing his naked backside as an expression of contempt. Then Dave Granlund closes this array with two images: the first, a picture of the Statue of Liberty—a symbol of America—declaring the achievement of a goal for women’s soccer, equal pay; the second is a quiet celebration of Mothers’ Day by a mother who is serving in the U.S. military in some land far-flung enough to require that the celebration be conducted through the mail. APO on the box tells us that it was sent via the Army Post Office. Time for another break.

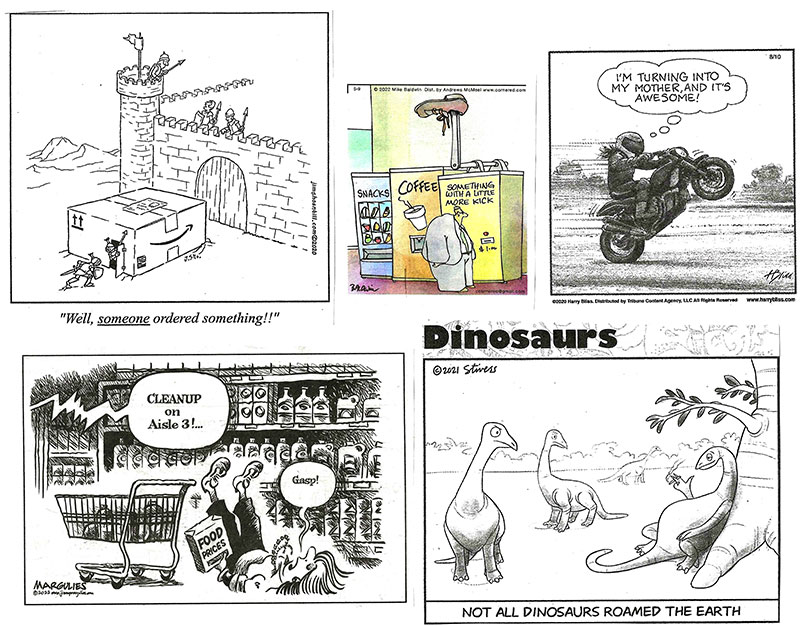

AS ALWAYS, the captions explain the pictures, producing comedy. Mostly. The comedy in some of these gag cartoons comes close to evading me entirely. The motorcyclist turning into his mother? What’s that about? But the first cartoon—the package from Amazon that probably contains a Trojan horse filled with soldiers—is clear to me, but not terribly funny.

The next collection is, I ween, better. Funnier. I like the sound of one dog barking best. After that, the hummingbird and then the lumberjack’s response to the save-the-trees team. That cartoon and the clean-up on aisle 3 on the previous page veer off in the direction of editorial cartoons. And the clean-up, signed by an editoonist, was unquestionably produced as an editoon. Enough break. Back to work one last time.

THE OPENING CARTOON is Joel Pett’s examination of Mitch McConnell’s political philosophy. Pett cartoons for the Lexington Herald Leader in Kentucky, and that’s McConnell’s home state, so McConnell, one of Kentucky’s two senators, is a frequent Pett target. JEREMY: INSERT Edit(429a)16 SAME SIZE NOT THUMBNAILS HERE; THEN DELETE THESE CAPITAL LETTERS. In fact, McConnell appears to have no political convictions at all—except those that allow him to retain his power. That’s it. I’ve thought that for the longest time, and now I’m happy to have Pett, in effect, agreeing with me. Next is Mike Peters whose imagery quickly reveals that the pot is calling the kettle a puppet: Tucker Carlson is the puppet of Putin. Then Dave Whamond shows us that the American public’s fascination with sensational events leaves it too distracted to notice what is happening to its democracy, which is being stolen behind their backs. And then Pett is back with a picture of the cluelessness of the Kentucky state legislature, which apparently can’t see that no raises in teachers’ salaries probably causes many teachers to leave the profession, thereby creating the shortage. In our next collection, we ponder what several editoonists have to say about student debt. Pat Bagley’s 4-panel cartoon shows us a college graduate who, having tossed his cap into the air in celebration of his graduation, wonders what has become of it. And what is it? Is the cap a symbol of achievement? Or just of a diploma, nothing more. At the very least, having graduated, the graduate is puzzled to discover how little that achievement means.