|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 412 (news thru December 28, 2020).

Here’s “part two” of our seasonal extravaganza that reviews a half-dozen

’TIS THE SEASON, KIMO SABE The Plague of the Trumpet

SULLIVANT AT LAST! Brand New Book on Legendary T.S. Sullivant

*STIR CRAZED IN PLACE Surviving the Pandemic during Lock-Down

NOUS R US *Summing Up the Comics Year by Michael Cavna 50 Years of Price Guidance *Charlie Hebdo Accomplices Found Guilty in Paris Kent State Graphic Novel Wins PW Poll Wimpy Kid Author Beats Lock-Down Cartoonist Arrested for Possessing Child Porn

ODDS & ADDENDA Cartoonist Christmas Cards at NCS Website

Further Ado Leonard Pitts, Jr. On the Christmas Spirit *CARTOONISTS IN A TRUMP-FREE WORLD Four Cartoonists and Their Views

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Christmas Issue of Mad Bad Mother No.4 Hellboy by Adam Hughes Miles to Go No.2 Sacred Six No.1 American Ronin No.1

TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating and Delusional Buffoon in Chief

* EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy

BIRTH OF A POLITICAL CARTOONIST Bob Englehart

The Difference between Republicons and Democrants

THE FROTH ESTATE Time’s Person of the Year

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Adults in Peanuts—A Historic Once & Other Strange and Wonderful

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Review Of—: Henry Speaks for Himself

Rancid Raves Gallery Charlie Brown Hugging Snoopy Figurine

*BEHIND THE SCENES WITH LINUS AND ST. LUKE How Charles Schulz Got His Way with “A Charlie Brown Christmas”

Civilization’s Last Outpost Trump’s Corrupt Last Days

*EXCELSIOR! A Panel of Stan Lee Fans

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: The Nutcracker Gahan Wilson Sunday Comics *A Wealth of Pigeons: A Cartoon Collection The New Yorker Cartoon Issue

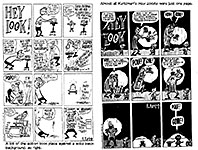

BOTTOM LINERS Single Panel Magazine Cartooning

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status The Book Tour *The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Will Durst Needs Help

PASSIN’ THROUGH Richard Corben Ken Spears

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND—

“If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

‘TIS THE SEASON, KIMO SABE Everywhere I look, pundits are complaining about 2020, what a rotten year it was, what with the pandemic and the plague (by which latter I mean Trump), the rupture of the nation’s economy, widespread unemployment and homelessness, protests for racial justice and equality in a nation laced with systemic racism, entrenched poverty, a broken criminal justice system, police violence, and Trump inaction. Herewith, more-or-less at random, are some of what’s being said (mostly about the Trumpet)—: Trump had questioned the legitimacy of elections, attacked the free press, called for the arrest of his political opponents, encouraged white supremacists, violated anti-corruption safeguards, implemented nepotism, advocated measures that limit voting, sought more control of the civil service, claimed unbridled executive power, treated the federal government (even the White House grounds) as his own private duchy, and embraced despotic leaders around the world. After the 2020 Election was called, Trump branded the results a “fraud,” insisted he had won, and asserted that victory had been stolen from him by left-wing radicals, corrupt Democrats, and the media. He signaled to his supporters that American democracy was utterly crooked—that they shouldn’t trust the results—and many leaders of the Republican Party joined in this treacherous subversion of the Election. ... But beyond his post-Election tyrannical tantrum, the most significant bad news was this: after a full term of Trump displaying disdain for democracy, immense ineptitude (including a pandemic response that led to the preventable deaths of tens of thousands), and unabashed malice (marked by racism, misogyny, crudeness, and cruelty), Trump gained support among Americans. ... Nearly half of the electorate and an entire political party accepted, if not fully applauded, his war on democratic norms. ... With millions of Americans blase about or, worse, energized by Trump’s wide-ranging assault on democratic values—as well as his attacks on reality, rationality, and science—a threat to the political core of the nation remains, even without Trump in the White House. ... The Election demonstrated that this virulent current [of authoritarian impulses] existed beyond Trump’s narcissism. And this moment raises a pressing question for the nation: can a slide toward authoritarianism be reversed? And that’s just from David Corn in Mother Jones. David Roth in The New Republic carries on in much the same spirit—: Donald Trump will leave the White House in a blaze of truthless tweets and hapless coup attempts. Did we really expect anything else? ... There was never a chance that he would respond to an electoral defeat in anything but the most egregiously undignified way. ... He would handle it poorly, and lazily. Out of spite and out of habit, he would make idle threats and lash out where and whenever it seemed safe [an important distinction: bullies always back down if met with even ordinary resistance]. ... This is Trump going out exactly as he governed—by telling someone whose name he’d soon forget to fix a problem he didn’t care enough about to understand, and then watching television to see how well he was doing. ...Trump never really knows anything about anything. As wildly irresponsible as his behavior has been since the Election, and as queasy as it is to watch him flail and fume and feint his way through what is either an exceptionally oafish attempted coup or the single most tasteless fundraising gambit in the history of American politics, the spectacle has mostly just been confounding. ... The American culture’s reflexive deference toward men born to wealth and privilege ... has not just coddled but cultivated his every poisonous whim. In that sense, his ham-handed flirtations with authoritarianism are simply the result of him being afforded one more scoop of ice cream just before bedtime. ... The unreasoning battle that Trump is fighting, down to the last moment, is the one he has been fighting all his life—not to lead or rule but to displace whatever is not him with his own sour self. He wants everything, always, if only to keep it from anyone else. At the end, as at the beginning, it is either him or us. That’s Roth. But the news media are full of phrases and fragments of criticism of the Trumpet—: Republican conservatism based upon the self-interest of the very rich. ... a deeply tribal, all-encompassing, information resistant ethnonationalism. ... a days-long torrent of falsehoods, obfuscation, evasion, misdirection and imprecision ... 25,000 false or misleading claims (twenty-five thousand) from the Trumpet ... he’ll lash out and try to create the illusion that he’s still dominant. ... the more erratic and unstable he’ll become. ... “Trump is going to go down fighting. And he’s not afraid to take all of us down with him” (Jeet Heer at The Nation). And then, there’s the Wall, symptomatic of the Trumpet himself. From The Week, December 18—: Trump inherited 654 miles of border structure along America’s 1,900-mile border with Mexico. Over 4 years, he’s constructed 415 miles, although of that total, only about 25 miles cover areas that had no previous barriers. The rest of the new construction replaced or reinforced existing structures. To accomplish what little has been accomplished, the administration has waived dozens of regulations regarding endangered species and Native American burial sites. Portions of once protected saguaro cactus forests have been cleared, and communities’ access to the Rio Grande and canals has been cut off. In Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, crews were blasting in a mountainous area known as the final resting place of Apache warriors who died in battle. “The heartbreaking thing is we’re watching them detonate these areas that will never be finished,” says Laiken Jordahl of the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity in Arizona. He calls it “a true desecration of indigenous land.” ... Trump believes that the wall he did succeed in building will stand as a monument to his presidency—a kind of anti-Statue of Liberty. ... Some of the most invasive construction now being conducted in New Mexico’s remote Guadalupe Canyon includes some of the “most endangered and critical habitats in North America. ...

The Administration has spent more than $8 billion of the $15 billion allocated so far, making the wall one of the largest infrastructure projects in American history. So far, none of the wall has been built with Mexican money. Yes, of course—that’s all true. But the year has had a huge upside, too. Sheltering in place for most of it means I have spent more time with loved ones. And any year that can arrange for that is not a bad year at all.

SULLIVANT AT LAST! My copy arrived on December 24, Christmas Eve. And it is a Christmas present the likes of which hundreds of T.S. Sullivant fans have been waiting for—for years. For decades. For as long as I’ve known and admired the comedic drawings of this cartooning genius. Entitled A Cockeyed Menagerie: The Drawings of T.S. Sullivant, it weighs in at 400 9x12-inch pages (b/w with a color section; 2021 Fantagraphics Books hardcover, $74.99). And it is everything Sullivant fans could want— a grand and glorious tome, encyclopedic in reach and scholarly in treatment. At the Fantagraphics website: “Fantagraphics is proud to present the most comprehensive collection ever published of Sullivant's delightfully off-kilter creations, which have not seen the light of day since their initial appearance in pioneering humor magazines over a century ago.” Yes, I had a role in creating this seriously humorous compilation. I collected most of the cartoons, scouring the old humor magazine Life through nearly four decades of Sullivant’s run in it, and I wrote a biographical appreciation for the Introduction. But Sullivant exceeds anything any single one of us could do: we all stand in his shadow. And now you can pre-order your copy of this landmark publication at fantagraphics.com

We’ll do a more expansive review next time.

STIR CRAZED IN PLACE During the Great Pandemic of 2020 AS I WRITE THIS, it’s been 40 weeks since my wife and I started sheltering in place. We started on a Tuesday, March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. And before this opus gets posted, at least two more weeks will have passed. And how are we faring? Candidly, pretty damn well. At our advanced ages, we never vigorously recreated outside much anyhow. I miss drives and walks in the mountains: to take them was one of the reasons we moved here thirteen years ago. But I can see the front range, bunched up at the western edge of the Great American Desert, just on the horizon. We live on the northeastern shoulder of the Denver metropolitan area in a housing development that is surrounded by open farmland. No tall buildings. Not many buildings at all except for the houses in the development. I can see a little of the front range from our front porch. And whenever we drive somewhere (to the grocery story or the liquor store—one needs sustenance at times like these), we see the mountains piled up against the sky in the west. So my privation is not complete. I’m retired from any money-making employment: the work I do is writing this online magazine for posting once a month. And Harv’s Hindsight, the history and biography department, also posted once a month. And I can do that just fine whether quarantined or not. In

fact, the lock-down hasn’t changed my daily routine much at all. I have been

living like this for almost twenty years, glued to the keyboard half-a-day at a

time. (Near here is a photo of what I see every morning when I report for

work—on the shelf just below the computer screen.) The lockdown has resulted in my writing more every month. The postings are longer. (More tedious, no doubt.) Dunno whether longer means better. That’s up to you. I’m enjoying myself. Just the same as I would if I weren’t sheltering in place, locked down and quarantined. I do a little more research these days. I write in the mornings and read in the afternoons. When tempted away from the ancestral manse in the olden pre-pandemic days, I’d waste afternoons wandering in stores, spending money excessively and not doing much research. Now that delinquency has been corrected. I go to the comicbook shop every 3-4 weeks. I miss going more often, but not because I need to buy more comics. I subscribe to a mail-order service, G-Mart: I order a month’s worth of comics from the Diamond catalog, and G-Mart delivers through the mail as the comics come in. So I get what I need, pretty much. I have relied upon the comicbook shop for DC Comics. Since DC’s withdrawn from the Diamond distribution system, the only way I know what Batman’s up to this week is by scanning the comics at the shop. And at this season of the year, I miss shopping—wandering malls and aisles amid throngs of people in a seasonal mood with Christmas carols hovering over it all. Instead, we shop remotely in the Web’s catalogs, viewing and picking and choosing online. The results come through the front door from the Postal Service. Kind of drab for a holiday. One of our amusements here is watching the neighbor’s dog. (How’s that for a comment on our pandemic times? Our entertainment consists of watching a dog.) Our kitchen window looks out over their back porch, where their dog does unusual things. It’s a Boston terrier and only six months old or thereabouts. The day after the snow fell, the neighbor kids piled up quite a lot of it to reach from their porch floor to the ground below, and they tapered it off as it descended so they have a snow slide. It’s too short to last long as entertainment for the kids, but then they got the dog involved. They brought out a plastic box lid, about two-by-three feet, and put it on the upper part of the snow slide. Then they put the dog on it and gave it a gentle shove. This make-shift snowboard went the four feet to the bottom pretty quickly. And—lo and behold—the dog liked it! Now whenever they play snowboard with the dog, when the thing reaches the bottom of the snow slide, he hops off and takes the thing in his mouth to return it to the top of the slide. Fun to watch. And so we do. Stirred but not shaken.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

SUMMING UP THE COMICS YEAR At the Washington Post, Michael Cavna attempted to sum up the comics year, and it wasn’t all bad. True, comic shops were shuttered by the hundreds, he began. Cartoonists canceled long-planned bookstore tours, and the grand gatherings from San Diego Comic-Con on down became virtual versions of themselves. “Given such obstacles, 2020 was the year that the comics industry could have taken cover, merely trying to survive,” said Cavna. Yet graphic novelists and other comics storytellers adapted and rose to ongoing challenges. Authors hunkering down at home became Zoom ’toonists, sometimes drawing remotely for fans, sometimes reading their works to school-age audiences in quarantine. And by the fall, North American graphic novel sales were up more than 40 percent — boosted significantly by manga and the “Dog Man” publishing empire of Dav Pilkey. Cavna then goes on to briefly outline five of the main comics trends “that helped define 2020, along with the books that propelled the industry to new heights.” Herewith, Cavna—: 1. Comics representation mattered. Amid the year’s reckoning over race in America, graphic novels continued to give voice to once-underrepresented stories, and creators of color drew critical acclaim. Shortly before George Floyd’s death sparked international protests, Gene Luen Yang and artist Gurihiru released the graphic novel “Superman Smashes the Klan.” ... Other heralded culturally diverse stories included “Almost American Girl,” Robin Ha’s illustrated memoir about suddenly relocating from South Korea to Alabama as a teenager; “When Stars Are Scattered,” in which Victoria Jamieson helps tell Omar Mohamed’s true story of growing up in a Somali refugee camp; and “Long Way Down,” as Jason Reynolds’s free-verse story got a graphic-novel adaptation with artist Danica Novgorodoff. Plus, “Class Act,” Jerry Craft’s latest book about middle-school life, arrived months after his “New Kid” won the Newbery Medal. 2. Comics fed the quarantining soul. As in-person comics conventions from coast to coast toppled like dominoes, creators and fans were missing these bonding pilgrimages. And one of the best recollections of this life was Adrian Tomine’s “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist” — released during the summer’s virtual Comic-Con — in which the acclaimed author offers sharply felt insights into how he experiences this specific culture. [Reviewed down the scroll.] Other graphic novel types explored sports and music 3. Politics was front and center. Comics collections that lampooned President Trump were plentiful, including Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury” book “Lewser!,” Tom Tomorrow’s “This Modern World” release “Life in the Stupidverse” and Ruben Bolling’s “Tom the Dancing Bug” compendium “Into the Trumpverse.” Yet broader and more historical takes on politics were also abundant. The most powerful of them all was “Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio,” a deep journalistic dive into the still-resonant ’70s tragedy by Ohio native Derf Backderf (“My Friend Dahmer”). [I reviewed it in my Hare Tonic column at the Comics Journal online, tcj.com.] 4. LGBTQ representation keeps growing. Trung Le Nguyen delivered a sparkling debut with his graphic novel “The Magic Fish,” about the child of Vietnamese immigrants who teaches through fairy tales — yet wrestles with how to come out to his family. Also noteworthy were “You Brought Me the Ocean,” by Alex Sanchez and Julie Maroh, “The Times I Knew I Was Gay,” by Eleanor Crewes, Sophie Yanow’s hitchhiking-toward-discovery tale “The Contradictions,” and Noelle Stevenson’s memoir, “The Fire Never Goes Out.” 5. Youth was served. As young readers attended school from home, they could take breaks with deft new illustrated literature, much of it almost nostalgically set in schools. The year’s best YA books included Terri Libenson’s “Becoming Brianna,” Lisa Brown’s “The Phantom Twin” and Maria Scrivan’s “Nat Enough.” Then there were Pilkey (“Dog Man” and “Cat Kid” books) and Jeff Kinney (“Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Deep End”), who helped power the kids’ market with relentlessly strong sales — a trend that shows no sign of flagging in 2021.

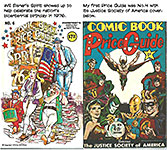

50 YEARS OF PRICE GUIDANCE The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide celebrated its 50th year this year. It began in 1970, which is just about when I started buying comicbooks again after a hiatus of about 15 years when I was indulged in such “grown up” and therefore comicbook-less activities as college and the U.S. Navy. Overstreet commemorated the present occasion with a “special 50th anniversary edition” that doesn’t look much different from the non-commemorative edition. To

celebrate the occasion, I ordered the book with a cover by Todd McFarlane that

depicts Spider-Man and Spawn clinging to a lively looking gargoyle. Inside,

it’s pretty much the same as always. The Market Report runs from p.89 to p.176,

and a list of the Top 100 Golden Age titles joins front matter articles on Big

Little Books, the Pioneer Age (1500s-1828), Victorian Age (1646-1900), Platinum

Age (1883-1938) and a long piece “Batman Gothic Genesis” with an emphasis on

Gardner Fox. The alphabetical listing of comicbooks and their prices begins on p. 354 and runs to p.1,132. That’s 779 pages of prices. I bought my first Price Guide with No.4 in 1974. It has a cover by Don Newton depicting the Justice Society of America. Newton did several covers in the early years. Overstreet did the covers for the second and third editions; the cover of the first edition simply depicted comicbook publisher’s logos. Overstreet recruited Joe Kubert for No.5, who covered it with Tarzan. After that, the cover artist was usually a professional. With No.6, Will Eisner joined those ranks. And then with No.8, Bill Ward shows up, treating us all to a pulchritudenous portrait of his Torchy in one of her form-fitting, er, “gowns” to celebrate “women in comics” with sexy pictures of various superheroines in scanty attire—scarcely the sort of festivity women’s rights demand. The same kind of desecration occurs on the cover of No.44.

“All of the artists over the years have been very supportive,” Overstreet said at the 40th anniversary of the Price Guide. “Will Eisner was always there for me, and so was Carl Barks. In fact, Carl drove from California to Tennessee [where Overstreet lived] to meet me. He wanted to see the ‘factory’ where the Guide was created. He was shocked to see that the production of the book, from beginning to end, was a one-man operation. I was working full-time for a paper company as their statistician and drawing maps of their operations. I did the Guide in my spare time.” Compared to the current edition’s 300-plus pages of advertising and essays, the 1974 edition, which starts the alpha listing on p.38, has ads and articles that are virtually non-existent. The alpha listing ends on p.452, after 414 pages; this year’s alpha listing, remember, is 779 pages long. That’s a measure of how the comicbook market has grown in 50 years. It’s almost doubled. And the number of advisors (comicbook shop owners and collectors) has grown, too. For several years (maybe still; I dunno), Overstreet convened an annual meeting in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee to discuss markets and prices. “After that meeting,” Overstreet said, “I would have a good feel for the market and how many titles were coming in, and who was buying what. The most important factors were how many books existed, the supply in certain geographic areas, and what the prices where.” This year’s anniversary special edition costs $29.95; the first Price Guide in 1970 cost $5. That was a pretty steep price for a 6x9-inch pamphlet of 32 pages. A Special Collector’s Reproduction of the first Guide was published in 1993; we’ve paired it with the 50th edition in our first illustration, above. A mint edition of Action Comics No.1 (Superman’s debut) was priced at $300 in the first Guide; this year, that comicbook in mint condition sold for $4,600,000. Mint prices for Military Comics, $70 and $8,800; Fantastic Four, $30 and $190,000; Gleason’s Daredevil, $100 and $24,500; Captain America, $150 and $550,000. Captain Marvel and other Fawcett titles weren’t even listed in 1970. One thing that hasn’t changed much: the black-and-white photos of comicbook covers are still too small to read—just as they were in No.1. But then, we don’t need to “read” the pictures, do we? We’re interested in the prices not the pictures.

CHARLIE HEBDO ACCOMPLICES FOUND GUILTY Fourteen people associated with the 2015 attacks on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket on the outskirts of Paris were arrested, tried for three months in Paris, and found guilty of involvement by a panel of French judges on Wednesday, December 16, reports James McAuley at washingtonpost.com France, far more than any other Western nation, has been a constant target of Islamist terrorists in recent years. More than 260 people have been killed here in attacks since 2012. But given the particular emotional significance of the Charlie Hebdo shooting, the verdict in this case “represented a national catharsis.” Of the 14 defendants, three were tried in absentia and five were spared the charge of terrorist complicity, sentenced only to involvement in a criminal conspiracy. The trial was hugely symbolic for France. The actual killers are all dead. The brothers who killed 12 people at the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris on January 7, 2015, were killed by police after a two-day manhunt. An accomplice, who was responsible for a related attack at the Hyper Cacher kosher supermarket on Jan. 9, 2015, that left four people dead, was killed at the scene by police. The defendants in the resulting trial were accused of either criminal conspiracy or terrorist complicity in the attacks. Ali Riza Polat, 35, was accused of having provided weapons to all three killers, charges he denied. The judges handed him the heaviest sentence of the 11 defendants present for the trial — 30 years in prison, 20 without parole. Charlie Hebdo marked the start of the trial in early September by republishing the caricatures of the prophet Muhammad, ignoring a strict prohibition in the Muslim faith on any image of the Prophet. France has suffered three terrorist attacks since then, including the gruesome beheading of Samuel Paty, a public school teacher in the Paris suburbs who had shown his students those caricatures. France’s President Emmanuel Macron’s emphatic defense of the right to publish the pictures drew ire and inspired protests across the Muslim world, and a security guard was stabbed outside the French Consulate in Jiddah, Saudi Arabia. In an interview with Al Jazeera in late October, Macron said the caricatures should not be seen as symbols of the French republic, although he added that he would not compromise on the right to publish them. The cartoons have continued to haunt France. The first of the recent attacks came in late September, when two French journalists unrelated to Charlie Hebdo were stabbed outside the newspaper’s former Paris office by a 25-year-old Pakistani man who appeared not to have realized that his target had changed location. The second was the mid-October beheading of Paty in broad daylight by a Chechen asylum seeker. That attack followed a social media campaign by a Muslim parent angered that Paty had shown the caricatures to students, although the man’s own daughter had not been present in Paty’s class on the day in question. In the third attack, in late October, three people were fatally stabbed in a basilica in Nice by a suspected Tunisian migrant who had arrived in Europe shortly before. Richard Malka, the attorney for Charlie Hebdo, spoke with emotion after the ruling. “It’s the end of something today, but I hope as well that it’s the beginning of something else: I felt, I believe — at least I hope — an awareness, an awakening, a desire to act, among citizens against a danger that kills, that wants to impose fear and terror,” he said. “This danger is not Islam — that has to be said clearly. This danger is Islamism — that is to say, a fascism — and we cannot find excuses for it.”

KENT STATE GRAPHIC NOVEL WINS PW POLL Released in September during the 50th anniversary year of the 1970 tragedy, Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio (Abrams ComicArts) by veteran comics journalist Derf Backderf garnered the majority of votes in PW’s annual Graphic Novel Critic’s Poll, receiving eight votes from a panel of 14 comics critics. In this deeply researched work, PW Staff reports, Backderf, best known for his Eisner-nominated 2012 graphic nonfiction work My Friend Dahmer, reconstructs the lives and last days of the student activists and bystanders killed when the National Guard fired on unarmed antiwar protesters on the campus of Kent State University. “The book presents a nuanced portrait of the equally young National Guardsmen, who were under extreme pressure and suffered from a severe lack of training, while deftly examining the polarized political context, anti-communist paranoia, and rampant government surveillance surrounding the anti-war movement during the Nixon administration.” The title was also chosen as a 2020 PW Best Book of the Year. Calling the title “one of the year's most tragic and insightful books of any genre,” PW comics critic Chris Barsanti praised the “weave of research and personal drama” in a methodical account of the watershed event that critic Rob Clough described as “even-handed but unrelenting.” PW critic Sarah Mirk said the book represents a timely effort to reexamine the events at Kent State during a period in American culture fraught with similar political polarization. Backderf, she said, “illuminates societal dynamics that feel eerily parallel.” My review is running in my column Hare Tonic at the online Comics Journal, tcj.com And we’ll have it here, too, in a couple of weeks.

WIMPY KID AUTHOR BEATS LOCK-DOWN Over the summer, Jeff Kinney and his publishing team were trying to figure out how to safely promote the second Rowley Jefferson book, which had already been pushed from April to August due to Covid-19. Livestream events seemed like a no-go, reports Hannah Yasharoff at USA Today— his core audience of kids roughly 8 to 12 years old was already getting an overload of Zoom time through school. The solution, Yasharoff reveals: Kinney would travel around in a van and dole out books to kids via a 7-foot golden trident that young readers could connect to the new book’s storyline and associate with the cover’s bright orange and yellow color scheme. It was a socially distant way to still let kids meet the man who created their favorite characters during a time that doesn’t allow for much in-person interaction. “I wanted to do something physical,” Kinney said. “I was really surprised by how well-received it was, even though it was literally me just handing kids a book with the trident, and I was really surprised by how grateful parents were and how happy kids were to have something to do that wasn't canceled.”

CARTOONIST ARRESTED A cartoonist famous for his work in The New Yorker has been arrested in the Hudson Valley, New York, for alleged possession of a sexual performance by a child, reports D.D. Degg at dailycartoonist.com Why do journalists do that? Why do they include the name of a famous magazine in a report about child porn? Probably because there would be no story without The New Yorker reference. I’m going to report this story without The New Yorker to see how news-worthy it is then; to wit—: A cartoonist, Dutchess County resident Daniel “Danny” P. Shanahan, 64, of Rhinebeck, was arrested by New York State Police on Wednesday, December 9, and charged with possession of a sexual performance by a child, said Trooper AJ Hicks. According to Hicks, the materials were found on his computer after a warrant was obtained by the Village of Rhinebeck Police. Danny Shanahan could face up to four years in prison, followed by 10 years of probation, if convicted as charged. Over the course of his career as a professional cartoonist, Shanahan has contributed cartoons to Time, Newsweek, New York, The New Yorker, Fortune, Playboy, Esquire, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Chicago Tribune.

ALL ACCURATE, FACTUAL REPORTAGE. But most reports also include something like this (in italics): Shanahan is a longtime New Yorker cartoonist whose work last appeared in the magazine’s February 20 issue last winter. Such a reference is unfair to both Shanahan and The New Yorker. Unfair to the cartoonist because his career is more broadly based than his association with that magazine. Unfair to The New Yorker because it connects the magazine to a charge about child pornography—as if, somehow, The New Yorker approved of child porn (maybe, even, fostered it). So why do it? Because, as I said, without The New Yorker, there is no story worth publishing. But the sensationalizing in this case didn’t end with The New Yorker. Kathy Reakes at dailyvoice.com continues by extending the sins being reported: Earlier this year, Shanahan's son, Render Stetson-Shanahan, faced murder charges in the brutal stabbing death of his college roommate Carolyn Bush, a fellow Bard graduate. The story made national headlines in 2017 because the Rhinebeck High School graduate and longtime Samuel’s Sweet Shop employee was the son of the famous cartoonist, Danny Shanahan. Render Stetson-Shanahan, was found guilty of manslaughter following a jury trial. A sampling of Danny Shanahan's cartoons may be found here. Me, again. See? They don’t let up. And I’m guilty sometimes, too; after all, I’m a journalist. Not only does The New Yorker promote child porn, they sponsor murder. Geez.

ODDS & ADDENDA At the National Cartoonists Society website, they’re wishing us a better new year that they hope will be enhanced by viewing a cornucopia of cartoonists' Christmas cards, which you can see here —:

https://www. hoganmag.com/ blog/7065

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Here’s what Leonard Pitts, Jr. wrote at the Miami Herald. And since he’s the greatest syndicated columnist of our age, I’d like you to have the privilege of reading it; so here it is—:

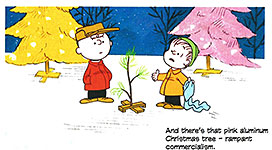

And so this is Christmas. So sang John Lennon in 1971. The Vietnam War took 2,414 American lives that year, so the song was a prayer of harmony and peace with a scrim of irony. Nor did the irony end there. Lennon was shot to death nine years later, 40 years ago Tuesday. And if the events of 1971 seemed sharply at odds with the hope of the holiday, the same can surely be said of 2020. On the surface, things seem much the same as they ever were, the same crush of manufactured joy and consumer avarice Charlie Brown’s been complaining about for 55 years. On TV, the same photogenic families stand in the driveways of the same upscale homes, beckoning you to buy a luxury car to celebrate the night when, Christians believe, heaven touched Earth. But this Christmas is not the same. It is a pandemic Christmas where death is already setting new records. Nearly 2,900 lives were lost in a single day last week, roughly equivalent to a 9/11 every 24 hours. The CDC says COVID-19 may have claimed nearly 330,000 of us by Dec. 26. Healthcare workers are physically and emotionally spent; the system is cracking under the strain. And so this is Christmas. But what is Christmas when you can’t — or at least, shouldn’t — travel? To go over the river and through the woods to grandma’s house this year is to risk exposing her to a deadly virus. Yet any year that denies you the ability to go home, to gather in a place of memory with those you love, is a year that steals something irreplaceable. That’s why carols written during World War II brim with such palpable yearning.

“I’ll be home for Christmas, if only in my dreams . . .”

“From now on, all our troubles will be out of sight . . .”

“I’m dreaming of a white Christmas, just like the ones I used to know . . .” How those words must have felt to some man sweltering in the jungles of Guadalcanal. Small wonder the Christmas that came at war’s end — 75 years ago — was “the greatest celebration in American history” in the words of Matthew Litt, author of “Christmas 1945.” It’s a book one is hard-pressed to read without smiling, tales of soldiers, sailors and Marines rushing on crowded roads and rails to get home for Christmas and people doing for one another with cheerful, thankful hearts. Americans seemed moved by something deeper than manufactured joy and consumer avarice that year. When sailors stepped off their train for a Christmas Day layover in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, the 1,200 residents met them with turkey dinners and gift-wrapped presents from beneath their own trees. A British mother wrote the only American whose name and address she knew — New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia — pleading for something impossible to find in war-ravaged Europe: a doll for her daughter. It was booked on a Pan Am flight and reached London on Dec. 23. This year there is, again, a need for something deeper. Something like they found in North Little Rock, Arkansas, last month after a black family erected a Black Santa Claus in their yard only to receive an anonymous note demanding removal of the “negro” elf. Iddy Kennedy said it made her wonder “if this was the right environment to raise our daughter.” Then her neighbors learned of the harassment. There are now black Santas up and down the street. People also sent money, over $1,000, which the family has redirected to the Arkansas branch of Ronald McDonald House Charities. Speaking to the Washington Post, Executive Director Janell Mason called it “humanity doing good things.” And so it is. And so, this is Christmas.

CARTOONISTS IN A TRUMP-FREE WORLD How Will They Fare? Steven Heller, writing his Daily Heller at printmag.com, looked ahead to January 20, 2021, wondered how editoonists will fare once the Trumpet has left the White House. “He will take with him the flawed persona that was a perfect foil for cartoonists, caricaturists, illustrators and acerbic artists in all media. “Like Nixon,” Heller continued, “Trump's egotistic and autocratic tendencies have fueled critical graphic commentary for four challenging years. So, from the comedic point of view, his absence may be met with both relief and remorse.” Hoping to find out how editoonists are thinking, he assembled four of “the most prolific contemporary visual satirists, visible on covers of national and international magazines—Edel Rodriguez, Barry Blitt, Steve Brodner and Ross Macdonald—to comment (and lament) on what Trump's forthcoming White House vacancy means to them now and for the future.” And here’s what they are thinking—: Said Ross Macdonald: “For four years, the president and his toadies have provided such a target-rich environment for satire that it’s hard to know what the future looks like, and how quickly Trump will fade. The general feeling I’ve heard expressed is that everyone is looking forward to having the news cycle slow down and be boring, and not having to hear about the latest Trump outrages 10 times a day. “But

somehow,” Macdonald continued, “I wonder if he’ll grant us any ease. He’s

developed an appetite for dominating the world news cycle, so he’ll probably

keep trying with hourly tweet-storms, pushing ever wilder conspiracy theories,

slagging Biden with every breath, throwing himself in front of the cameras

every chance he gets. And the media will report on him because—love him or hate

him—he’s a reliable eyeball-getter. In his own words, he’s the Golden Goose. “I hate to admit he’s right about anything, but he was right about that. So, I suspect he’ll be providing subject matter for satire for a few months at least, maybe longer. By then there’ll probably be plenty of Republican lawmakers trying to grab the spotlight with foul Trumpian antics, since they’ve seen how outrage worked for him. And maybe we’ll still have Mitch McConnell supplying material. He’s fun to draw too.” Once aroused, Macdonald kept on: “Other illustrators have said that they look forward to never having to draw him again. I look forward to him being out of the White House, and I won’t miss hearing about him from sunup to sack time every day of the week. But I won’t stop drawing him; it’s too much fun! I will miss having such a big, easy target. He could be relied on to provide a barrage of material. The dogged ignorance, obvious lies, inept buffoonery and vile corruption just kept coming in wave after wave. “Combine that with his Trump-ness,” Macdonald finished, “— the big suit that never changed, the red tie, the imagineered hairdo, the bad orange self-tanner, the lummox-like walk and tilted posture, the little eyes, delicate flitting hands, and that mouth. And he felt like the gift that kept on giving, for satirists, anyway. His wretched terribleness was not funny, but at least he looked funny doing it.” Edel

Rodriguez, who produced some spectacular Time covers, said he won’t

miss Trump at all. “I was thrilled to watch him lose the election and glad to

see Biden be elected as the new American president. I definitely feel that my

mission was accomplished. My only goal was to see Trump impeached or voted out

of office. I think he has been one of the most dangerous people this country,

and the world, has ever had to deal with. I don’t think it’s completely over,

as he has stirred something in a certain segment of Americans, but his hold on

power is sure to diminish and disappear.” Barry

Blitt, who’s made a career out of doing covers for The New Yorker, doesn’t

think Trump will go away. “He’s the Babe Ruth of negative American stereotypes.

He's brought a face to a lot of unsavory attitudes; I expect he'll be lurking

around the corner in a whole lot of cartoonist's work, mine included.” “I can’t think that any serious literate American, artist or no, will miss him,” Steve Brodner said. “But the media will very much, I fear. He was made by a mainstream press that couldn’t believe the great free show they got every day. ... CBS’s Les Moonves admitted it in the beginning: ‘It may not be good for America, but it's damn good for CBS.’” Brodner challenged the people working in media: “Can we all now understand what we created? We cannot put the sludge back in the pipeline. The pollution is widespread. Trump leaves as a cultural icon. This has been compared to a Gnostic cult, where Trump is the god figure; information of any kind is twisted to fit into a network of absurdist paranoid conspiracies. “Millions

who didn’t ever think about politics before are now cultists, resistant to

news, science, Calling Trump “the first American dictator,” Brodner went on: “Luckily he was too stupid and lazy to achieve it. We are so fucking lucky! We bought a little time to ring democracy with steel. I have already decided to draw Trump very little from now on. It is our chance to make him irrelevant. So, let’s do that. No more oxygen from anyone. He only has nonsense to dispense. Let’s give ourselves the luxury of starving Trump for a while. As John Lennon might say: Trump is over. If you want it.”

QUOTES & MOTS During an interview, John Lithgow answered a question about why we are delighted by poetry—by rhymes—saying: “It’s because they go off like little firecrackers. You know a rhyme is coming any time you get to the end of a stanza, but you hope the best rhyme of all comes at the end of a poem. And it’s just a surprise. ‘Omigod, yes, of course!’ It captivates you and holds your attention in a remarkable way.”

READ & RELISH The amount of sleep required by the average person is five minutes more.—Playwright Wilson Mizner The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.—Isaac Asimov Education costs money, but then so does ignorance.—Statistician Claus Moser

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

HAPPY HOLIDAYS!

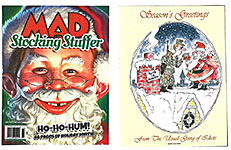

The Christmas issue of Mad is out, decorating the magazine shelves of

supermarkets everywhere with a jolly picture of Alfred E. Neuman wearing a

Santa beard. And the all-reprint strategy that governs this publication

nowadays has emerged into full light. A 96-page re-issue of a “special

edition,” the magazine offers 37 separate articles, each of which is dated

(with issue number) in the table of contents: it’s clear that the 60-plus-year

history of the magazine published enough Christmas articles through the years

that a “stocking stuffer” can be assembled from the past holiday issues. The

reprint scheme makes me wonder, though, whether the artists and writers get

residuals. The same sort of culling and mustering of pieces on single topics prevails at other recent (or current) issues: No.15, out just last month, is the “superspoofheroes issue”; and No.16 is the “horror” issue. The only bad thing about the StockingStuffer is that in giving it a square-back binding, the gutter inside overlaps itself, covering up portions of the artwork on facing pages. The Usual Gang of Idiots are present in these issues— Tom Richmond on tv and movie spoofs, Paul Coker (doing “the 25 worst things about Christmas”), Dave Berg (who is actually no longer with us: he died May 17, 2002), Al Jaffee on Fold-ins (although No.15 has a new guy on the feature, Johnny Sampson), Angelo Torres, and so on. New-ish among them is Emily Flake, a refugee from The New Yorker. Sergio

Aragones occupies 17 of the StockingStuffer’s 96 pages with visits to

“after Christmas,” “Winter,” “Santa,” “New Year’s Eve” etc. Plus his tiny

microscopic marginals throughout. The most spectacular of Sergio’s offerings is

a 2-page spread showing a few thousand people at a shopping mall, all

misbehaving in the usual manner of human beings everywhere. We could study this

landscape for weeks. Features in the superhero spoof include “Ecch Men,” “Superheroes Based On Real People,” “Nitwit Teenage Turtles,” and “Bat Boy and Rubin,” a comicbook reprint from Mad Comics No.8, December 1953. Tiny type on the first page of each article identifies its initial appearance. I suspect, though, that Sergio’s “Mad Look at Quarantine” might be freshly concocted: seems entirely too pertinent to be a reprint. Ditto the 2-page commemorative spread on Mort Drucker, who died just last spring, April 9. Tom Richmond, another superb caricaturist, drew the pictures and wrote the tribute to his legendary predecessor who, Richmond avers, did 300 parodies for Mad.

I AM ASTONISHED as I encounter yet again another brilliantly competent artist on the latest comicbook title I pick up. Where do all these superb artists come from? They can’t all be graduates of the Joe Kubert school. Can they? And they are all, without exception, beautifully competent storytellers. Here’s

No.4 of the 5-issue run of Bad Mother, for instance. In this issue, the

woman who has kidnaped the Bad Mother’s daughter sends a couple of assassins to

kill BM (aka April). The spread at hand begins a 6-page fight, all conducted

without speech balloons or captions. No words. Just pictures. In the spread at hand, April is in front of a mirror as the killer comes up behind her. She sees him in the mirror, and we see him, too—in the mirror. Apart from his threatening image, we also see the barrette she has in her hair, an elaborate metal design that says “#1 Mom.” The progression of images on this page keeps #1 Mom in front of us even as we see the killer advance. Then on the next page, when April throws her head back into the killer’s face, we realize as he exclaims “Fuck” that the prickly #1 Mom barrette has jabbed him in the face, causing him to drop the cord he was strangling BM with. All nicely done. I dunno why Mike Deodato Jr. breaks the page into 16 “panels,” some with no picture in them, when the story is told, in effect, in four panels. Why provide 16 focal points, which is what the division does. I understand that the last three panels on the second page—showing her terror-stricken face and her hands reaching out, grasping—focus on visual elements that express her terror. But what about the sixth panel? The one with a star-spot of light on the killer’s face but otherwise just a black blob? What’s that all about? After winning the fight and killing the killer, April goes to the murderer’s car parked outside and captures the killer’s sidekick, who happens to be the kidnapper’s son. Then once he’s tied up and gagged, she phones the kidnapper, lets her hear her son say “Mom?” and invites her to dinner. Go back and look at April’s face as the killer wraps a strangling cord around her neck. Every picture is like that: flawlessly rendered.

AND HERE’S a

page from a Hellboy and the BPRD one-shot, “The Seven Wives Club” drawn

by Adam Hughes, who, it seems to me, draws covers more than stories. But

this story is masterfully drawn. The staging is deft even if much of most

pictures is heavily cloaked in solid black shadow. Hughes knows just how much

of the picture to illuminate for storytelling purposes. And he also shows us

regularly the beautiful face of the heroine of this piece; no one is better at

beautiful female faces. Then Stephen Molnar in Miles to Go No.2 produces this page, starting

with a wonderfully atmospheric street scene then going inside a bar and then

flashing back to the old man and the young woman in the car and finishing with

a glimpse of a young woman reading a book, which leads into the next page where

the young woman has a larger role. The drawing itself is terrific—flecks of

shadow in an almost Caniffian manner. Next

to that page, we have a page from No.1 of Sacred Six by Gabriel

Ibarra, drawn, wherever perceived through deep shadow, with a wispy penline

feathering, completely different from, say, the multi-panel pages, each panel

an extreme close-up of some pictorial fragment of the story, by artist Aco in American Ronin No.1. The focus is microscopic: you wouldn’t think a

visual narrative could be conveyed in such tiny fragments. But Aco’s artwork,

while not at all photographic, is detailed and precise. Where, I ask, do all these surpassingly competent artists come from? Why haven’t we seen any evidence of the brilliance of their work before now? Or have we, and I’m just forgetting. Whatever the case, it’s clear that American comicbook illustration has passed well beyond the Jack Kirby - Wayne Boring vastnesses, which were competent enough themselves, to these isles and inlets of exquisite rendering. And it’s drawing by itself which is so impressive—lines on paper, no high-tech massaging. Different styles but the same level of superior drawing ability. And here, all this time, I thought we’d somehow left the Age of Illustration behind us. Nope: it’s invaded the four-color fold, where it amazes as it amuses. Wonderful.

TICS & TROPES “So, the toddler president is finally taking baby steps to begin the transition to the incoming Biden administration. ...” —Editoonist Nick Anderson But the cowardly Republicon Congress has yet to do anything to defray its emerging reputation as a conglomeration of idiots and fraidy cats. Let’s take names of those who have maintained a stoic silence. And then let’s vote them out of office first chance we get. No country can be governed by fools and cowards.

TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating and Delusional Buffoon in Chief TRUMP WAS NOT VISIBLE for at least nine days in December, the 14th through the 22nd, a period that history will denominate “The Big Quiet.” Unheard of. We’ve not used to this. We’re accustomed to the cacophony of his constant tweeting and to the imagery of his posturing in front of whatever camera is in sight, making a thumbs-up sign. He’s obviously sick: his ego has been struck a blow that it cannot quite withstand. Under

the heading of Trumperies, we screen editoons that have the Trumpet as their

sole subject—Trump as he often sees himself and Trump as others not in his cult

see him. Handily in the former category is Dave Granlund’s portrait at

the upper left of our first visual aid. The strutting self-importance embodied

in this image is perfect for the Trumpet. Next around the clock is Patrick Chappatte, who builds an entire cartoon on Trump’s long red tie. The image, invoking that of a statue in a town square, shows Trump tripping on his tie, a convenient representation of Trump tripping himself up with successive contradictory statements. Across the bottom of this display are two This Modern World comic strips by Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins). Perkins does not deploy imagery to make his point: instead, he piles up sarcasm until it is nearly overwhelming. Sarcasm as a needle poking fun at something is tricky: it’s easy for a reader to misinterpret sarcasm, taking it to mean what it says instead of meaning the opposite. In the first panel of the strip at the lower right, for example, the actual Trump is precisely not doing “everything possible to facilitate a peaceful transition of power.” Again in the fourth panel, the speakers describe exactly what Trump cultists are doing. In this strip and the next, Perkins hones the sarcasm, concluding, finally, with a panel in which a penguin named Sparky and a Boston terrier named Blinky comment on the preceding action; they are recurring characters, and their speeches are the only ones in This Modern World that are not sarcastic. Another

of Perkins’ strips shows up in the next array, but we pause first at Pat

Bagley’s cartoon that offers an image of the Grandstanding Obstructionist

Pachyderm getting its tongue frozen to the flagpole, which will happen on days

of lower temperatures if you persist in kissing the Trumpet’s flagpole. Once

stuck, you can’t escape. You become, instead, a toothy grinning model of

cheerful servility—like the image Nick Anderson provides in the next

editoon. Below that, John Cole offers a visual metaphor of Trump as the three monkeys of lore and legend, who hear no evil, see no evil, and speak no evil. But in Cole’s usage, the third monkey (Trump himself) is speaking utter nonsense (i.e., “evil”), and the traditional slogan deteriorates—“Speak No ... No ...um, Never Mind.” To be free of Covid-19 infection, the Trumpet had to pass the testing that doing what the monkeys demand represents. Trump failed the Covid-19 Test metaphor. And that brings us to the last of our Trumperies for this opus, another installment of Tom Tomorrows’ This Modern World, in which Trump is the chief speaker, uttering actual Trumpet remarks with a slight twist, giving the whole sequence a deeply sarcastic tinge. And with that, we move on to serious editoons rather than sarcastic ones.

CLIPS & QUIPS Every joke is a tiny revolution.—George Orwell Despair is always rational, but hope is human.—Novelist Richard Flanagan EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THIS SLOGAN, riveting in its mockery, I stole from Will Durst, who has manufactured many more comedic slogans during his life as a political comedian. His columns, always caustic, usually begin with a sustained metaphor that vaults over itself again and again until it is thoroughly worn out by the time he abandons it. But not before strangling a good laugh out of us. Here’s a blurb about Will: A Midwestern baby boomer with a media-induced identity crisis, Will Durst has been called "a modern day Will Rogers" by the L.A. Times while the S. F. Chronicle hails him as "heir apparent to Mort Sahl and Dick Gregory." The Chicago Tribune argues he's a "hysterical hybrid of Hunter Thompson and Charles Osgood," although the Washington Post portrays him as "the dark Prince of doubt." All agree Durst is America's premier political comic. Will is now in trouble, doing a long recovery from a stroke he suffered in October 2019. Find out more Under the Spreading Punditry, which happens toward the end of this Opus. Just keep scrolling down. Here,

as usual in our Editoonery Department, we persist in examining a selection of

editorial cartoons from the last month. Our objective, as always, is to show

how editoonists use imagery and visual metaphors, to make statements about the

events (usually political) of the day. We begin this time, however, with

examples of editoons celebrating the holiday season we’ve just passed through. Dave Granlund starts us off at the upper left of our first visual aid. The image—of workers dining at a communal table—is given its import with the heading, “Thanks For Giving,” appropriate for the holiday Granlund is celebrating and for the workers whose efforts he is likewise celebrating. Next around the clock, we move into the Christmas season with Michael deAdder’s picture of the Trumpet stealing money from the Salvation Army’s bell-ringer, saying, by way of explanation, that “I’m really needy.” The reference is to the endless fund-raising that Trump and his minions are doing by pretending they are raising money to support Trump’s legal battles seeking to undo the Election. There is virtually no limit on what Trump may use this fund to finance; he can even just bank the money and draw on it for daily expenses. (Expenses which are all incurred by the Trumpet in the course of his court cases or his running for office again in 2024.) DeAdder produced this cartoon for the Counterpoint website, and he accompanied the cartoon with this statement: “Donald Trump continues to fundraise off the conspiracy that the last election was fraudulent. All that America can do is sit and watch and allow him to do it. He has exposed that much of the American experiment is based on the honor system. The entire system is dependent upon candidates behaving honorably because there seem to be few checks or balances to stop a President from corrupt behavior without scruples. Maybe that will be Trump's sole positive legacy—exposing the flaws in the system. Then again, America has to survive Trump before it can enact legislation to survive another leader like him.” The “honor system” deAdder describes is the “government by laws not men” that John Adams invoked while joining others of like mind in drafting the U.S. Constitution. The honor system is a game. To play any game, you must play by the rules, or the game degenerates and ceases to exist. One of the rules we have followed for a couple of centuries so far is that elections work: voters vote, and their ballots are counted, and the candidate with the most votes wins. The Trumpet has been breaking this rule, thereby threatening the continuance of the game. Back to our display with Jimmy Margulies’ imagery of the arrival of a New Year, who, personified as a new-born infant, reminds us that we still live under the regime of Covid-19. We conclude the comment on the seasonal festivities with David Fitzsimmons’ beautifully imaged Christmas—including that of a mother (wearing a mask) tipping a cup of coffee to her neighbors while surrounded by pet cats and her child. Fitz’s mascot, the prairie quail at the lower right corner, joins in the festivities with his own toasting cup and a wish for a Merry Christmas. And with that, we leave seasonal joy behind and examine editoons with a severely unjoyful political purpose.

THE TWO-MONTH PERIOD AFTER the Election was dominated by two events: the Trumpet’s refusal to lose and the invasion of the Plague, still. We’ll take up the first first because it is accompanied by the antics of the Trumpet, who never fails to amuse. Adam

Zyglis gives overturning the Election a fresh meaning by having the Trumpet

confuse that expression with the unturning in “No Stone Unturned,” thereby

drawing our attention to another of Trump’s post-Election activities— creating

new scams and harvesting more donations. Next is Lisa Benson whose imagery fits Trump’s never-ending effort to bend reality to his will: he may have taken second place, but he’ll treat it as a triumphant win. Just another lie at which he is so adept at creating. Then Zyglis again with a sound-alike construction (“conceited” and “conceded”) and an image that shows how long is the line of Presidential candidates, who, defeated at the polls, conceded the Election to their opponents. Not, of course, the twitterpated Trumpet. Trump’s

refusal to accept the verdict of the Election is analyzed in our next exhibit. Signe

Wilkinson shows Trump resolutely confronting reality and overwhelming it

with his enduring lie—that he won. No matter how the eye chart reads, Trump

reads it differently. Michael Luckovich’s image reveals the only way

we’re going to get the Trumpet to leave the White House. Steve Sack changes the subject somewhat, turning to the pardons that the Prez is issuing over the last weeks of the year. The Trump children are leaving the White House and taking valuable parts of it away with them—but then Jared Kushner cautions them to await pardoning before stealing the Presidential silverware. Accompanying

all of the Trumpet’s efforts to overturn the results of the Election has been a

chorus of worry about what damage he is doing to democracy and our other social

and cultural institutions. Mike Luckovich’s visual image of a car being

driven repeatedly into a wall, hoping to knock it down is one interpretation of

these events. The car is labeled “Trump’s Cronies” and, as an observer notes,

“They’re dummies.” Ed Wexler is similarly blunt: his visual metaphor shows Trump about to light a fuse that leads, we presume, to explosives that, when ignited, will blow up the White House —and all the democratic institutions it represents. The culprit is ol’ big-assed Trump. Matt Wuerker’s cringing Lincoln is reacting, as are the GOPachyderms in the corner, to the mere presence of the Trumpet. His shadow is enough to cause negative reaction, inspiring fear in the elephants and shame in the Lincoln memorial. Chip Bok’s two panel cartoon shows us Trump’s contradictory attitudes and policies about elections: yes, Georgia’s forthcoming run-off election is rigged, but go out and vote for the Republicon candidates anyway. To

any setback, Trump’s programmed reaction is to sue. So far, his hope for

undoing the Election by pseudo legal means has been almost universally rejected

by the courts. (At last count, over 50 of his suits have been defeated or

dismissed.) One of David Hitch’s crisp talking heads seems to be a

somewhat grisly Scrooge stating the principle by which he operates, hoping

Trump will do the same. Next around the clock, Daryl Cagle has the Trumpet being defeated in court in the bluntest visual image possible. Jack Ohman takes Joe Biden’s view on such matters: every loss for the Trumpet is the same as another victory at the polls for Biden. And Rob Rogers conjures a visual metaphor that represents the “higher power” Trump is seeking—and shows how that power is likely to react to yet another baseless fraudulent claim. The

transition from a Trump White House to a Biden White House is not as smooth as

it might be; the Trumpet is making it as difficult as possible by not

acknowledging Biden’s win, his “right” to whatever records and information

might make his assumption of Presidential power easy. Next, Nate Beeler’s image shows how impossible the situation has become with Trump as far into denial as he was before, finally authorizing the official beginning of the transition. The picture shows Trump denying even the law of gravity which is certain, eventually, to catch up with him. Trump’s own demise is imminent in Beeler’s picture, a consequence of the success of the transition. And while the transition proceeds at whatever pace Trump allows for, David Horsey summarizes the vote count situation at the lower right. Among the statistics: the Trumpet saying his 306 electoral votes constitute a “landslide” but, according to Trump math, Biden’s 306 electoral votes do not; the chance that Trump will ever concede thereby admitting he lost—a big Zero; and, another Zero, the number of Election lawsuits won by Trump. Then Phil Hands invokes the season to capture the Trumpet’s state of mind as he loses lawsuit after lawsuit In

the midst of his frustration and electoral agonies, the Trumpet launches his

last campaign—to pardon as many criminals as he possibly can, which, as Bill

Bramhall pictures, acts as “herd immunity from prosecution.” I don’t know

how that works, exactly, but apparently Trump knows. Then Jeff Danziger gives us a little drama in which the Trumpet stoutly maintains that he is the Prez even as white-coated attendants put him in a straight jacket before escorting him to the nearest facility for the mentally incompetent. The effectiveness of this cartoon depends upon its having several panels in which to show how persistent the Trumpet is in his idiotic claim. The punchline, the final panel with another insane person claiming to be someone he’s obviously not, is a vivid indictment of Trump’s sanity. Finally, Scott Stantis supplies an image that shows how far into his delusion Trump has demonstrated himself to be. So far that he’ll even show up on Inauguration Day to be sworn in.

WHILE THE TRUMPET

remains the most popular of subjects for editoonists—he’s a ready-made joke—Joe

Biden hovers on the horizon, making the transition function despite Trump’s

attempts at sabotage. The danger is not quite so much as it might otherwise be:

Biden’s been in the White House before and knows where all the levers are. Ted

Rall, however, is not convinced as his cartoon opening our next exhibit

demonstrates. Rall, apparently a progressive of the most aggressive sort, is

not about to accept or join in the Democrant fun. His imagery shows the world

going up in flames whilst Democrant realists ignore it. Next, Patrick Chappatte shows us what is likely to happen when Biden arrives at the White House to take over the executive branch of government. The Trumpet is still inside—and he’s still threatening Biden. Then Bruce Plante’s Biden contemplates the wreckage of government that Trump leaves for him to inherit and to fix. (And Cahoots, my pet rabbit, can’t resist a comment of his own, just to clarify the situation as we see it.) Dana Summers’ image of the Biden Administration with an old man at its head, an antique auto with a few superimposed technologies, may not be reassuring, but Bronco Bama promises to drive, which makes us feel better.

THE PANDEMIC,

the other Big Story of the day, attracts editoonists’ attention in our next

collection. Rob Rogers at the upper left compares the death tolls of

three American tragedies—Pearl Harbor in 1941, the 9/11 attack by Islamist

terrorists in 2001, and the number dying every day of Covid-19 in 2020. Every

day the plague is killing more Americans than either of the two other

disastrous events. Emily Flake at The New Yorker chooses to

comment on the less astonishing and homier facets of the pandemic’s arrival. Authorities recommended three actions that would impede the spread of the infection: staying home and away from other people, wearing facial masks, and practicing “social distancing” (staying at least six feet away from people not in your household). The results of following these recommendations over the months since the Covid-19 arrived here last February has resulted in a serious change in our nation’s life styles. The

first thing, the most obvious, was that we could no longer “go out,” as Lisa

Benson demonstrates at the upper left of our next visual aid. Her image

turns a “snow globe” into a “no globe,” around which cluster ad hoc snow flakes

with prohibitions on them. Even Santa Claus feels the cramp of new

regulations: “working from home” tells others that (a) your working but (b)

you’re also “sheltering in place,” according to Jeff Danziger. The

surprisingly quick development of a vaccine marked the next phase in the coronavirus

plague. Jimmy Margulies ridicules the Trumpet’s announcement about the

impending discovery of a vaccine by seizing on his use of the “ducks in a row”

metaphor; then the ducks, representing Trump’s Covid-19 policy, start

quacking—or, alternatively, calling Trump names that are accurate. Trump knows

too little about the vaccine or any science to be able to predict when a

vaccine might become available. But as it turns out, he was right. In the first panel of his editoon, Walt Handelsman presents the next problem that the vaccine cure must face; in the second panel, he offers a remedy, which, immediately below, Andy Marlette, envisions. Then Jeff Stahler’s visual metaphor illustrates the dimensions of the problem with a picture of a classic maze. The

arrival of vaccines raises another specter—that of a few legions of crazies who

won’t take a vaccine because they believe the injection will give them measles

or premature dementia or some other fictitious malady. Their refusal simply

makes life more hazardous for us as well as them. Gus(?) Clement captures

the perversity of the anti-vaxxers at the upper left of our next

collection. I suspect that the only way to read Pat Bagley’s cartoon with Rudy holding out his hands at the ass-end of a horse is that Rudy is there to collect more horseshit for his voter fraud lawsuits, none of which have succeeded. Then Gary Varvel’s Santa imagery makes an observation about Congress’s heralded relief bill. The Trumpet has since managed to pressure an increase in the amount of the check (over his signature) from $600 to $2,000, but Varvel’s message is the same: the taxpayer, me and thee, will be paying the amounts the checks are cashed for —whatever those amounts are. Other

issues are collected in our next display, beginning with all the fuss about

Facebook. Bill Bramhall offers an interpretation of Congressional

cynicism. Next, David Hitch produces another of his talking grotesques

to rehearse the history of the name of the Cleveland baseball team, which has

decided not to call itself “Indians.” Finally, Matt Davies’s visual metaphor shows Covid-19 arriving from England by airplanes full of contaminated passengers, while a concerned citizen invokes an antique cry about British invasion of the (then) colonies. Before we get to the end of this posting, we pause with editoonists to ring in the New Year, an annual event that political cartoonists usually turn into some sort of statement about the state of the world/nation/Trumpet. Chris Britt’s imagery does a lot of the ringing with bells representing the usual assortment of Trump-induced attitudes —and the Trumpet himself directing the ensemble that’s playing “Trumpism.” About this imagery, Britt wrote: “During his vulgar and corruption-filled term as president, Donald Trump has waged a war against democracy. And the cult members of the Republican Party have gleefully and dutifully followed their dear leader’s direction.” Next

is Scott Stantis’s image of a giant-sized Trumpet “welcoming” the new

year, a tiny infant who is entirely intimidated by the Trumpet’s bulk. Quite a few editoonists depicted the Year 2020 as Death, carrying a scythe, as does Chip Bok at the lower right. Quite rightly, he has the New Year infant terrified—and running away. Jeff Koterba cheers us up by imagining a light at the end of the 2020 tunnel, signaling an end to the agonies. We applaud the sentiment while also doubting its accuracy. Still, we hope you’ll have a happier new year than last. We

finish with a editoonist’s farewell to one of editoonery’s great practitioners, Tom Toles, in which, employing the imagery of a big game hunter, Toles’

numerous targets’ heads Other images at hand include a Toles cartoon from his student days compared to a sample of his work 50 years later, and this year’s Christmas stamps from the Postal Service—a sparkling display of holiday colors in traditional shapes. Just a somewhat delayed “Merry Christmas” from all the roystering gang here at your neighborhood Rancid Raves.

BIRTH OF A POLITICAL CARTOONIST By Bob Englehart, Erstwhile Editoonist at the Hartford Courant During the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 as John F. Kennedy and Nikita Kruschev held the fate of the world in their hands, Englehart, then an art student in high school, had an epiphany—: I saw a way that I could do my very small part to defeat the Communist Soviet Union threat and be paid for my effort. I started drawing freelance political cartoons for the morning paper, found a job as a full-time political cartoonist in Dayton, Ohio and after five years there, moved to Hartford, Connecticut and The Courant [where he spent most of his career]. In November of 1989, the Berlin wall came down, and the Soviet Union collapsed. I told the president of the Los Angeles Times News Service that I’d accomplished my goal, that Russia had been defeated and that I was going to leave political cartooning. He talked me out of it, saying there will be more demons to vanquish. He was right, of course. All I have to do is read today’s news, but I’d accomplished what I wanted in the beginning. Everything since then is a bonus.

The Difference between Republicons and Democrants Judging from the legislation they propose, Republicons think people are out to gyp the government (and all of us). It’s the logic of projection: they project onto others the ideas and feelings and practices they themselves indulge in. They see themselves in others (and don’t like what they see). Democrants on the other hand want to help and to fix things that aren’t working; they think people are essentially good but occasionally need a helping hand. Republicons want to built their own power and use it to enrich themselves and enfeeble the general population, denying to others what they grant to themselves. Democrants, like I said, want to help people.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution MAN OF THE YEAR, Woman of the Year, Person of the Year— Time magazine is slipping. Or maybe the expression is “Time magazine is adapting to changing times.” Used to be—back in the days of my yore—that the Man/Person of the Year was described by Time as that individual who had the greatest impact upon the news that year. It was a news-oriented distinction. By

this definition—which guided Time for 40-50 years—the Prez of the U.S.

would probably be picked every year. Time knows there’s a problem here:

it admits, in the current issue with Joe Biden and Kamala Harris on the cover,

that every “elected President since FDR has at some point during his term been

a Person of the Year.” I suppose the magazine has an unspoken rule that no Prez can be Person of the Year more than once. Because no Prez has been POTY more than once. And so we are spared the spectacle of Trump’s orange visage on the magazine’s cover again. In recent times, Time has shrugged off the “impact on the news” criteria. Instead, the magazine has chosen some person who serves as a “symbol” of some major trend in the news. Last year’s Greta Thunberg as Person of the Year symbolized the climate change crisis because she was so outspoken about it. And she spectacularly floated all the way from England to the United States in the 60-foot racing yacht equipped with solar panels and underwater turbines. She chose sailing rather than flying because an airplane’s emissions would contribute to the problem. And she didn’t want to be a party to that. So the trip was announced as a carbon-neutral transatlantic crossing that demonstrated of Thunberg's declared beliefs of the importance of reducing emissions to protest the failure of the world’s governments to take any realistic action. And so, Time tells us, the Biden-Harris “Person” of the Year symbolizes the “arduous quest for a more perfect union. For changing the American story, for showing that the forces of empathy are greater than the furies of division, for sharing a vision of healing in a grieving world.” “Furies of division,” I like the turn of that phrase.

READ & RELISH Wikipedia sites are viewed by more than 6,000 visitors per second and accessed by over 1 billion devices every month.

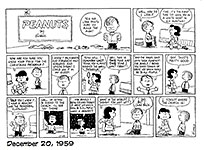

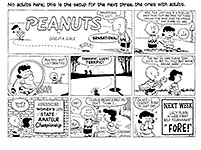

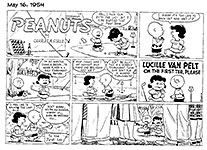

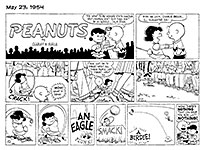

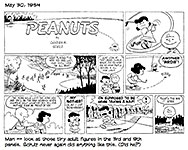

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping ADULTS, AS WE ALL KNOW, NEVER APPEARED in Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. Well, that’s all we know. Adults did appear, once— but mostly as legs— in three Sunday Peanuts strips in 1954—May 16, 23 and 30. The three offer a mild continuity, which is launched May 9, and we’ve posted all four ri’chere.

To the best of my knowledge, Schulz never drew adults in the strip again: it was as if he decided to try it out and see what happened. And when nothing did, he never tried it again.

STRANGE YET

WONDERFUL DEPARTMENT. Take Jim Toomey’s Sherman’s Lagoon,

f’insance. It’s characters are all underwater denizens. Sherman is a shark.

Ditto his wife Megan. Sherman’s best friend is a sea turtle. But most of the

time, the comedy in the strip isn’t shark-ish or underwater-ish. Both of the

gags in the samples we’ve posted near here don’t need the characters to be

sharks in order to be funny. Sometimes we encounter a joke that is about

Sherman eating human sunbathers on the beach. But most of the time, the jokes