|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 389, Part Two (February 28, 2019). Here’s the other half of that whopper opus, which includes a refutation of sexist charge against editoonist Steve Kelley, anniversary issues and cartoons in The New Yorker and Playboy, plus Esquire comedy; five book reviews, editoons on the Pope’s summit, an essay on the origins of celibacy, and farewells to Batton Lash and Tomi Ungerer. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

Oscars for Comics

THE FROTH ESTATE Another Watergate Soap Opera

Editoonist Kelley Is Not Sexist

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL

More Ted Rall Being Pissed

BOOK REVIEWS Terms and Conditions: The Graphic Novel The Unknown Anti-War Comics

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO An Expedition Into Magazines and Gag Cartooning—: Esquire Cartoons The New Yorker Anniversary Cover New Yorker Cartoons & Emma Allen Playboy (Another Anniversary) Other Gag Cartoons Elsewhere

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Dry Country The Stranger Miss: Better Living Through Crime

COLLECTOR’S CORNICHE Harvey’s Hirschfelds

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy Pope Francis’ Sex Summit and Celibacy

PASSING THROUGH Batton Lash Tomi Ungerer

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

OSCARS FOR COMICS (February 25)—“Black Panther,” the first movie based on a comic book to be nominated for an Oscar, didn’t win. The Oscar went to “Green Book,” which is about a black musician traveling through the Jim Crow South with a white man, a somewhat disparaged feel-good “interracial buddy tale.” It was another victory for anti-racism, and there were more black faces on stage last night than I’ve ever seen at this event. Movies about race rang up more nominations than any other classification: “Black Panther” had 7; “BlackkKlansman,” 6; “Green Book,” 5. That’s 18 total. But if Marvel’s Black Panther didn’t win, Marvel’s Spider-Man did: “Spider-Man—Into the Spider-Verse” won best Animated Feature Film. And best of all, during the Memorium segment that spotlights significant persons who’ve died during the past year, Stan Lee showed up, and they used a couple seconds of one of his cameos. Nice. He was dubbed “writer” and “producer.” While we’re up, here are a couple more irks and crotchets about the awards—: My wife Linda and I were hoping Glenn Close would get Best Actress for “The Wife.” Her performance was better than superior, but she emerged with only one more notch on her belt: with seven nominations, she remains the most-nominated living actor never to win. But Best Actress went to Olivia Colman for her performance in “The Favorite.” We saw only five of the eight nominated Best Pictures, and this was one. It had more nominations than any other—ten! But we thought it was one of the worst movies we’d ever seen. Three of its ten nominations were for acting: in addition to Colman, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz were up for Supporting Role. Good performances, no question. But the movie? Ugh—our reaction to its story rather than acting or costuming or set design or anything else about it. “Roma,” with 9 nominations, didn’t seem up to snuff. It wasn’t terrible like “The Favorite”: it was just awfully ordinary. Ordinary people reacting ordinarily didn’t seem to us like Oscar material. We also saw “Black Panther,” and Linda liked it. I, on the other hand, was baffled by it, as our posting of Opus 388a reveals. We both liked “BlackkKlansman,” too, but we didn’t think it Oscar-worthy. And we saw and loved “Bohemian Rhapsody” and hoped it might win Best Picture. It collected the most Oscars, four, including Best Actor, Rami Malek, who said in accepting the award: “We made a film about a gay man, an immigrant who lived his life unapologetically himself. We’re longing for stories like this.” Bravo.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution TRUMP’S IS THE SOAP OPERA PRESIDENCY. Every day, a new installment from the twitterpated Trumpet, another juicy tidbit, another tantalizing affront to common sense and traditional American political values. And the perpetually craving news media—whether the insatiable 24/7 regime of cable tv or the desperately expiring daily print newspaper—rush all over themselves to “cover” the latest, to broadcast these tweeted Trumperies for all the world to witness, thereby giving new life, day by day, to the freak show in the White House. The Trumpet is serving the news media its daily ration, and reporters eat it up without thinking, losing their journalistic sense through simple neglect and abdicating their responsibility as they go. The Watergate scandal marked the last time the news media were so thoroughly seduced into abandoning their principles. And Watergate, too, was a daily soap opera. Every day, a new installment, a new crime, a new criminal. Every day, fresh excitement. The soap opera ruled. Actual news seldom rose to our attention. We were addicted. Ditto the news media. It took years for the news media to recover from the excitement. Once Watergate was solved and Richard Nixon banished to his California compound, the salivating news media had nothing to put in its place. They were starved for a continuing story, for fresh injections of daily excitation. For another soap opera. Watergate effectively killed off responsible journalism. An entire generation of reporters had to be trained anew in the principles and practices of their craft, a craft traditionally without soap or opera. And once Trump is defanged, we’ll have to traverse the same desert again, years of foundering around in search of a fresh soap opera, a new continuing “story” to foster the excitement of yore—i.e., the Trump era. And then more years of defining what, after all, a “story” is, what journalism is, what responsibility is. And learning that soap opera is entertainment, not news. Or journalism.

TICS & TROPES It seems no one can adequately explain the reason that women tend to strike matches away from themselves while men tend to strike them toward themselves.—ReMind

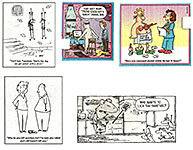

EDITOONIST ATTACKED FOR SEXIST CARTOONS Cartoonist Steve

Kelley, who says he leans right and who joined the Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette last fall after award-winning stints at the San Diego

Union-Times and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, recently got into

hot water with some Pittsburgh readers for three cartoons displayed nearby, all

published by the Post-Gazette within a week or so. The Newspaper Guild of Pittsburgh wrote an open letter, saying: “The cartoons display a contempt for women and an obvious deep-seated prejudice against them. The cartoons are not witty, insightful or funny. They are a puerile recycling of ridiculous, outdated and hurtful tropes about women that have rightfully brought scorn upon the newspaper.” Andrew Conte, director of the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University, writes the “On Media” column at NEXTpittsburgh. He invited Kelley to sit down for an interview about the cartoons. Kelley agreed, and then opted to cancel the interview and instead wrote Conte a 7-page letter that talks about his perspectives on the cartoons, the subjective nature of humor, and the criticisms against him and his work. We’ll post the entire letter further down the scroll. Fired up on the cause of sexism or not, Conte interviewed Liza Donnelly, a prominent cartoonist whose work appears most regularly in The New Yorker. Since Kelley references the Conte-Donnelly interview in his letter, we’ll start with Conte-Donnelly, herewith—:

Andrew Conte: You agreed with the Newspaper Guild of Pittsburgh that recent cartoons by Steve Kelley seem sexist or misogynistic. What about them makes you feel that way? Liza Donnelly: All cartoonists should be able to draw what they want to draw. We have the freedom to do that in this country because of the First Amendment. But I found the three cartoons that we are talking about to be using old stereotypes that are unnecessarily negative towards women as a group. The jokes are based on the notion that women are gold diggers, duplicitous and use botox. The jokes are meant to create a laugh based on old-fashioned ideas about women — I am not saying we can’t laugh at ourselves, but these are tired stereotypes. AC: What care do cartoonists have to take to avoid attacking people who are not in privileged groups? In this case women or young girls? LD: For any group of people, cartoonists should avoid using stereotypes — particularly for those groups who have suffered at the expense of stereotypes for centuries and who still do not benefit from equality. AC: How are the best cartoonists able to make a pointed, or perhaps even controversial, statement without crossing the line of being unfair? LD: It’s very possible to do that without being mean to others; it just takes time to look for different approaches to whatever issue you want to draw about. An editorial cartoonist’s job is not always to simply entertain and get a laugh sometimes, but to point out something or start a conversation about an idea. AC: How do you in your own work try to raise issues to bring about awareness or stimulate new thinking? Can you provide an example or two of your work that you feel does this? LD: I have done many cartoons about gender equality and women’s rights; it would be hard to describe an example. I would need to show you [see the examples posted nearby]. I specifically try to break down old ideas, traditions, stereotypes in our culture. Cartoons are sometimes a good way to get people to see things freshly.

AC: Who are some cartoonists today who are doing really interesting work that highlights gender equality or diversity? LD: Ann Telnaes, Signe Wilkinson, Garry Trudeau, Kim Warp have always dealt with these topics, as have other editorial cartoonists, both men and women. I am not particularly well versed on some of the very newest cartoonists, but I know they are doing great work. The New Yorker is publishing many new cartoonists online, and sometimes they deal with ideas of equality. There is an online site called The Nib that has many cartoonists who get into the subjects of diversity and equality. AC: How difficult is it to be a woman who draws cartoons in a field that traditionally has been dominated by men and male perspectives? LD: Now I find the culture receptive to women cartoonists, and to ideas about women’s rights; that wasn’t always the case. Ten or 15 years ago, a cartoon about feminism would have been considered uninteresting or possibly controversial and not a topic for mainstream publication. Now I can draw and write about feminism, harassment, rape, inequality (mind you, that’s not all I draw about), along with many other creative people. It’s very much a topic on the table to be discussed. Things have changed during the course of my career, and it’s great because we need to hear from everybody.

NEXT is Steve Kelley’s letter, dated January 28, 2019—: Dear Andy: I read the column you wrote about three of my cartoons and the reactions they engendered. You included in it an interview with cartoonist Liza Donnelly. I’m writing to let you know that I found much of what you wrote — and what Ms. Donnelly said — curious. The blitz of letters to the newspaper about my work has many of the hallmarks of an organized campaign, with certain words and phrases appearing repeatedly among them. They almost without exception suggest the cartoons are misogynistic, aren’t funny, and their attempts at humor are rooted in the 1950’s or 1960’s. Of course, no one bothers to make an actual case for what they’re saying because the case really can’t be made. Whether something is or isn’t funny is a matter of personal taste. The notion that something published today is redolent of a bygone decade and no longer applicable is similarly an opinion — shared by some, discounted by others. My suggesting that there is a woman in the world who wants gender equality but likes that men pay for dinner cannot be construed as a display of hatred for half of the population of the planet. The suggestion that there might be a little girl somewhere who would prefer to divorce Jeff Bezos than to marry a prince isn’t all that far-fetched, much less an expression of hate. And a joke about a prominent politician’s well-known use of Botox is hardly out of bounds for political humor — those jokes were common about John Kerry when he ran for the White House (I should know — I drew one of them, and no one accused me of misandry). [As Kelley pointed out elsewhere, women in power, like men, should expect to see thmselves at the pointed end of cartoonists’ pens.—RCH] It is often the case that someone who would argue an indefensible point resorts to gross exaggeration and ad hominem attacks instead of linear logic and data. When addressing these cartoons, each of which depicts a specific situation, why is it rational to assert that the characters populating them are meant to represent all of the members of their gender? Do people do that with characters in novels, or sitcoms or movies? The predicate for my cartoon on eliminating traditional gender roles was a report from the American Psychological Association: https://hellogiggles.com/news/apa-toxic-masculinity/ It’s a report decrying “toxic masculinity,” released the day I drew the cartoon. After ingesting the story, I elected to challenge the notion that women suffer from men’s “stoicism” and “competitiveness,” both of which the APA recklessly maligns in its report. In the aftermath of the letters we received, which insisted that I was a victim of old-fashioned thinking about dating, I researched who pays at restaurants, especially on dates. What are the protocols now, as opposed to the 1950’s and 1960’s? Next are a couple of links for reference, each followed by relevant data that I copied and pasted from the story [starting with this one:] http://money.com/money/3319420/who-should-pay-on-first-date/: Authors Battista and Mendez both agree that it’s generally best for men to pay on a first date. Yes, even still in 2014—a time in which, as I myself have written, women often outearn men. But the fact of the matter is that men typically want to pay: in a poll last year conducted by LearnVest and T.D. Ameritrade, 55% of men said they thought the guy should take the check. As Mendez explains, many men feel fulfilled and accomplished when they see an opportunity to provide, even if it’s in simple ways like paying for a drink. Perhaps more importantly, paying is a way for him to preen. “Even a guy who doesn’t make much money if he really likes you will try to impress you to the utmost that he can,” says Battista As for women? “In my experience, 90% will be offended if a guy doesn’t offer to pay,” says Battista. [Battista’s “experience” is scarcely statistical; but other reports back him up.—RCH] Here’s the other link: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-bad-looks-good/201709/who-pays-first-date-why-it-matters: Research by Emmers-Sommer et al. (2010) acknowledged that abundant research indicates that heterosexual dating scripts remain quite traditional, with the man expected to ask a woman out, and to pay for the date.[ii] Their study further revealed that although modern singles believe it is appropriate for either party to initiate a first date, in reality, most men still do so. Taking these findings in context, there are many first date bill-splitting/paying scenarios that will not necessarily trigger false expectations, which some would argue might be for the best. A 2017 Wall Street Journal article by Khadeeja Safdar (“Who Pays on the First Date?: No One Knows Anymore—Online Dating, Evolving Gender Roles Complicate the Fake Wallet Reach”) reported that in an age of evolving gender roles and Internet dating, we are unsure about who should engage in “the reach” for the bill.[iii] Contrary to the beliefs expressed by Post-Gazette staff and readers, most dates involve a man asking a woman out and then paying the bill. The notion that some women like that is hardly despicable. [The reports Kelley cites are mostly about male attitudes, and Kelley’s cartoon is about a female attitude. But if his research is off-target somewhat, his conclusion—that “the notion that some women like that is hardly despicable”—is, if unscientific, at least persuasively common sensical.—RCH] My

cartoon about the Bezos’ divorce was based on a fusillade of stories about the

couple’s high-profile split. Somehow, my critics neglected to notice that

nearly all reporting on the subject featured the couple’s net worth prominently

in the story – many including it in the headline. One can deny the notion that

a girl wants to marry (or divorce) a man of means (or a prince, for that

matter), but I think it is reasonable to suggest that some do. Certainly there

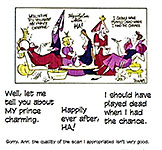

is ample evidence [posted nearby] from cartoonists [and these are both by] are

contemporary women. Ms.

Donnelly includes Ann Telnaes among her favorite cartoonists. [Near

here, I’ve posted] one of her cartoons that seems relevant: There are three women depicted, all of whom got the prince they wanted, only to discover that he was a disappointment. An amusing cartoon— at the expense of the prince each time. That’s apparently acceptable because Telnaes is targeting men, not women. Yet these three women all wanted the prince when he represented the fairy tale and all its trappings— castles, carriages, glass slippers. I have no problem whatsoever with the cartoon, and I find it quite funny. I just don’t accept that it’s okay to take men to task when they deserve it, but not women. It seems to do so would be sexism per se. Ms. Donnelly’s cartoons – in my opinion – do the same thing. Hereabouts are two she provided as examples of how best to deal with subjects who are not in what you both call “privileged groups.

Both of these are excellent, but they paint the women in them as victims, which I believe you [Andrew Conte] and Ms. Donnelly are suggesting makes them above the same reproach you level at my work. Indeed, Ms. Donnelly’s cartoons play to the notion that allegations made by women against men should be believed in an extrajudicial sense. Why is that okay? I try to avoid seeing people as members of groups. My job is to produce five amusing and provocative cartoons each week addressing the shortcomings of government or individuals, some of whom are women. In order to treat everyone the same, I look at no one as privileged or underprivileged. To do otherwise would mean that I’m not treating people fairly. A final subject I’d like to address is the casual use of the word “misogyny”, which means “hatred of women.” Pause and reflect for a moment precisely how unambiguously searing and offensive that word must be when directed at someone to whom it does not apply. It

strikes me as remarkable that people so easily offended by the thought of a

woman wanting a man to pay a dinner tab would willfully misappropriate such an

incendiary label. I wonder how my colleagues in the newsroom could reach for

that word when this cartoon of mine, posted near here [on the left], appeared

in their newspaper only two months ago. Likewise, would a man who hates women have drawn early in his career the second cartoon, the one [on the right] about sexual harassment in the workplace? One

of the cartoons I drew in 2005 has remained an all-time favorite among my

readers. It depicts a Part of the problem may be that as women become more integrated into positions of power, especially in government, some will undoubtedly say and do things – as men have done forever – that are foolish, ill-considered or illegal. Naturally, that will increase, not decrease the amount of criticism directed their way. I would encourage them – and the rest of us – to get used to it. Sincerely, Steve Kelley

AT LEAST ONE OTHER EDITOONIST commented that Kelley makes good points, saying Kelley was smart not to apologize. “I’m always amazed how little tolerance many on the left have for a range of opinion, especially on certain topics. We’re supposed to ‘celebrate diversity’ but sadly that seems to be only a one-way street to many. Hang in there, Steve. Many of us have had our turn being the focus of the free-floating umbrage brigades and it’s no fun.” As I pointed out in context, I’m not sure all of Kelley’s research on dating habits about who picks up the check are to the point. But Kelley’s own remark is right on: the notion that some women like their date to pay is “hardly despicable.” Take another look at what Kelley says his job is: to “produce five amusing and provocative cartoons each week addressing the shortcomings of government or individuals, some of whom are women.” “Provocative.” The intention is to provoke thought. Maybe laughter, too. But if laughter, the kind of laughter that leaves you thinking. Or maybe applauding. The provocation of the modern woman who wants her date to pay for dinner is to make us recognize that most of us are not perfect ideologues. We sometimes fall short of meeting our own ideals. By the same token, the little girl who wants to marry a rich man is expressing in modern terms the old little-girl-who-wants-to-marry-a-prince idea. Times change, sometimes with amusing results. And if we think about it, is it a destructive change? Should we get all exercised about it? Probably not. And maybe that’s what Kelley wants us to think. But I think Kelley has misinterpreted Telnaes’ cartoon with three women disparaging the princes they married. The target is not men. The target is foolish women—or, more precisely, the whole unrealistic fairy-tale idea. Still, apparently Telnaes received no complaints from women who might object to their gender being portrayed as so soaked in fairy-tale mythologies that reality escapes them. Maybe because lots of readers thought she was making fun of men. Or maybe because all Telnaes’ readers agreed with her about foolish fairy-tale romance. But none of her readers were looking for a crusade to go on, and apparently Kelley’s were. Or maybe Telnaes’ readers recognize that the cartoonist is female (“Ann” is sort of a giveaway) and therefore has a right to make fun of her sex. Who knows? And, finally, the botox joke. If you’re in public life, man or woman, you must expect to be criticized and, even, ridiculed for meaningless traits or failings. Trump’s hair. Obama’s ears. GeeDubya’s ears. Reagan’s hair. Things that have nothing to do with your competence. It just comes with the job. The botox cartoon is actually making fun of cartoonists who pick such pointless things to ridicule. It’s all human folly, the object of satire. Kelley may be right-leaning politically, but he’s also right, correct, in assessing and explaining his job as an editorial cartoonist. Bravo, Steve. (Er, yes—I know Steve and count myself among his friends.)

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping OKAY: I GIVE

UP. Michael Rhode: Stephan Pastis’ Pearls Before Swine is a continuation of a series where Pig had been going to the grocery store while depressed and drawing sad faces on grapefruits. Rob Smith Jr: I’m glad Michael explained the Pearls strip. In Bound and Gagged, I believe Dana Summers is depicting a patient whose insurance placement ended him in the maternity ward. That’s for any of us who have found ourselves being put in stupid medical places by “medical” insurance companies just shuttling people around. My father found himself being sent to an office that had nothing to do with his medical issues. But he had to go and no one would listen to reason. Of course that office passed on a bill despite the error. My father was told— as I and so many hear— “Don’t worry, the insurance company will pay for it.” What’s your interpretation? And then we get to penguins. Penguins, although plenty cute and comical, are not frequent visitors on the nation’s newspaper funnies pages. So it was something of a treat one morning to see penguins in two of the day’s comic strip line-up in the Denver Post. Chad Carpenter frequently assembles flocks (colonies?) of penguins in his Tundra. So frequently that for a while I clipped the strip whenever the penguins showed up. I suspect he uses photocopies of mob scenes like this so he doesn’t have to face the tedium of drawing them all over again. Penguins are regular cast members of Macanudo, the strip at the bottom of this visual aid, an import from Argentina. Although I generally applaud when new comic strips show up, I’m not keen on this one for at least three reasons. First, the comedy here is a bit too warm and whimsical for my taste. Maybe Argentines like it, but I doubt many American readers are overwhelmed with admiration. Second, I think the strip is supposed to be published in color. But since the Post doesn’t do color on its comics page, Macanudo appears in a dull black-and-gray. Not pleasing to the eye. And sometimes hard to discern the drawings. Third, if the Post wants to add a new strip to its line-up, why not pick one of the dozens of new strips by American cartoonists? Support local industry. We’ll have more to say about Macanudo at a later date. For now, we’re merely celebrating seeing two strips about penguins on the same day— a historic first, I’m sure. And if it isn’t, then to see two penguin strips on the same day, one atop the other just as they appear here— now, that is historic.

AND NOW I’M

STUMPED AGAIN. I can’t figure out the joke in any of these four cartooning

efforts. In Seth Fleishman’s cartoon at the upper left, the gag clearly has something to do with one guy getting both feet in concrete as compared to the other guy with only one foot. But what, exactly? And at the right, “Lex”? What? Since The New Yorker is published in New York, “Lex” is probably Lexington Avenue. But what’s the canon for and what does it have to do with Lexington Avenue? Is that guy preparing to shoot himself across Lexington Avenue? Is that somehow a joke? In Stephan Pastis’ Pearls, the joke has something to do with electronic “spam,” no doubt. Does Pig send a picture of a spam sandwich with all his e-mails because he doesn’t understand the difference between e-mail spam and the canned meat? Is that the joke? Pretty feeble. I get the joke in Bound and Gagged, but the drawing of the speaker gave me pause. Is this the historic first appearance in a newspaper comic strip of man boobs? Once again, I resorted to Facebook, putting all these up on my page, soliciting assistance from ardent observers. Stephen Worth: Top left is mixing how gangsters kill people with how pirates do... walking the plank with cement overshoes. Me: Well, this guy can't walk the plank. Both feet are encased in concrete. Abby Cronin: That's the joke. Torsten Adair: Mafia pirates. Mixing two different methods of water execution. Me again: Maybe the pirate aspires to being a modern criminal, so he's adopted gangster habits— pinstripe suit, encasing enemies feet in concrete. But when he tries to deploy the walking the plank notion, his aspirations are defeated. How obtuse is that? Typical New Yorker cartoon. David Allen Jones: Looks like the pig is working for the Hormel company, which makes Spam. If I had an email from Spam, I wouldn't read it either. Got nothing for the pirate one. I imagine it would be hard to walk the plank with your feet in cement; if that's the joke, well, why the hell is the other pirate wearing a business suit? The others are just kinda lame. Stephen Worth: Lower right, he’s tapping out a message on a talking drum. It isn’t written in text so you can’t do all caps. Jerome Sinkovec: Okay, the guy says that all the e-mails his company sends out are ignored. Then the last panel reveals that the company is SPAM. So all of the emails are treated as SPAM. See?? The lower left panel of the rabbit— I don't see the joke. Me: I don’t either, Jerry. George Garrigues: In New York, it's hard to get across town, so he uses a cannon? Heck, it ain't that hard; he could walk to Lexington Avenue.

THIS

INSTALLMENT of Kirkman and Scott’s Baby Blues gives me the

chance to stump for The Way to install a roll of toilet paper. In Funky Winkerbean, Tom Batiuk has deployed the most hackneyed cliche way of creating suspense. Mysterious letter arrives. Then what? Tune in tomorrow to find out. The other cliche way is this: hearing a knock at the door, Our Hero answers the door, opening it, and sees a man facing him and holding a gun. What then? Tune in tomorrow... The next three comics are all self-conscious about being a cartoon/comic strip. There’s a lot of that going around. In Brian Crane’s Pickles, Earl’s brother Leon shows up; he’s a world famous cartoonist. We’ll look at that later, when the sequence has had time to develop.

BLONDIE IS A PRETTY SEXY COMIC STRIP if you

look at it and think about it. Notice in the top strip, Blondie’s nightgown is slipping off her shoulder. Sexy stuff. The next strip features the Bumsteads kissing nonstop and pawing each other. More sexy stuff. Incidently, look at Dagwood’s eye in the final panel of the uppermost strip. Every time he’s depicted from the side, his eye (a long vertical dot) blends with the line forming his profile in one stroke. My sketch in the margin offers a better visual (even if I do say so myself). Next down the line, Rob Harrell’s Adam joins the legions of today’s strips that aren’t shy about referring to themselves as cartoons or comic strips. This self-consciousness destroys the illusion that the comic strip and its characters are in a separate but nonetheless real (to them) world. But that’s the price of making a good joke. (Or maybe a lazy cartoonist’s joke.) In Tundra, Chad Carpenter reminds me of a similar gag. Someone shoved over the Internet transom a few years ago a list of things husbands could do while accompanying their wives shopping (all of which are intended to persuade the wife never to insist that her husband come with her again). The last of them suggests that the husband go into a fitting room, wait for a few minutes, and then shout: “Hey! There’s no toilet paper in here!” That one makes me laugh out loud every time I think of it. To the right of Tundra is an iteration of Bill Whitehead’s Free Range panel, which the Denver Post (our local paper) treats cavalierly. It’s printed so small that you can’t read any of the words in it. And sometimes, you can’t decipher the pictures. I’ve positioned the panel next to a strip, both at the size they appear in the newspaper. The sign in the fourth panel (which I read using a magnifying glass) says: “Unfinished Masterpiece.” I wonder if Pastis got letters of outrage for making fun of LGBTQ in this Pearls. Of course, he’s not making fun of LGBTQ people, but in today’s climate of overheated sensitivities, I bet he got letters.

READ & RELISH The year 1998 saw the deaths of both my cowboy film heroes— Roy Rogers (born 1911) on July 6, and Gene Autry (born 1907) on October 2. Barry Goldwater (born 1909) died that year, too, on May 29; and Flip Wilson (born 1933) also, on November 25, merely 65 years old. Lloyd Bridges was 85 when he died on March 10. Just four days before, “The Big Lebowski” was released, the film for which his second son, Jeff, is best remembered. Presumably the father saw the son’s movie: he died of “natural causes” so was probably able to go to a theater to see it. But the fame of “the Dude”was scarcely anticipated at the moment of the movie’s debut, so maybe neither the father nor the son saw its release as momentous, and neither went to see it then.

TED RALL IS PISSED And Here He Airs His Righteous Anger As promised last time, here’s the whole of Rall’s report on his latest encounter with the California legal system. Rall is very angry, and his assessment (and reporting) is probably colored by his anger. He may avoid mentioning certain legal nuances. The legalities are complex and, like much law, obtuse. And he gets hung up on his conspiracy theory. But that doesn’t mean he’s wrong. I encourage anyone interested in justice and American values to read it—and weep.

The Report By Ted Rall (January 22) I was wronged. All I wanted was a trial by jury, a right enshrined in Anglo-Saxon legal tradition in the Magna Carta 803 years ago. Is this still America? No. America is dead. Not only have I been denied that fundamental right, I have been punished for having had the temerity to seek redress in the courts. Justice is when wrongdoers are punished and victims are compensated. Instead, the California court system has provided Anti-Justice. The wrongdoers are getting off scot-free. I, the victim, am not merely being ignored or brushed off. I am being actively punished. The ruling in Ted Rall v. Los Angeles Times et al. came down last week. The California Court of Appeal ruled in favor of the Times’ “anti-SLAPP” motion against me. Anti-SLAPP law supporters, including the Times, say they’re supposed to be used by poor individuals to defend their First Amendment rights against big companies. But that’s BS. The Times—owned by the $500 million Tronc corporation when I filed suit, now owned by $7 billion biotechnology entrepreneur Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong—abused anti-SLAPP to destroy me. My case was simple. From 2009 to 2015 I was staff editorial cartoonist for the Los Angeles Times. I drew hundreds of cartoons, some mocking the LAPD and then-Chief Charlie Beck and criticizing them for abusing people of color and the poor. Not surprisingly, the LAPD hated me. Whatever. A new publisher, Beck’s pal Austin Beutner, took over in 2014. It was one of the sleaziest political alliances in a city famous for incestuous politics. Like other newspaper companies, Tronc was desperate for money—so they turned to Beutner. As new publisher Beutner appears to have midwifed the purchase by the LAPD pension fund of millions of dollars of Tronc stock via a Beverly Hills-based investment company called Oaktree Capital, turning the LAPD into the Number One shareholder of Tronc, parent company of the Times. A few months the Los Angeles Police Protective League (LAPPL) gave Beutner its 2014 “Badge and Eagle Award” for supporting the police “in everything they do.” LA Times’ Ethical Guidelines prohibit Times employees from receiving non-journalistic awards or prizes. [But that, apparently, didn’t matter.] One year later, in 2015, Beck asked publisher Austin Beutner to fire me because I had annoyed him and the LAPD, and to smear me so I couldn’t work anymore. At this point, of course, the LAPD effectively owned the Times so Beck was Beutner’s boss. Adding to the web of conflict, Beutner wanted (and still wants) to be mayor of LA or governor of California. The problem for Beutner was and is, he has no popular base. Angelenos don’t like him. The LAPD was Beutner’s only real political ally. So when Beck came calling, Beutner was bound to say “yes” to anything he wanted. So the Times ran two pieces announcing that I’d been fired, not for offending Beck—violating their own Ethical Guidelines, they kept his identity secret—but for supposedly lying in a blog post discussing my jaywalking arrest in 2001. I hadn’t lied. I told the truth. And I proved it. The “evidence” that I lied was an audio recording of my 2001 jaywalking stop made secretly by the cop. It was mostly inaudible. But when I had the traffic and wind noise removed professionally, a process called audio enhancement, it revealed that I told the truth when I said I had been handcuffed and that an angry group of onlookers had protested my treatment. (For a blow-by-blow report on the incident and all the encompassing developments, visit Opus 342a for August 2015.) “One hell of a defamation case,” a lawyer told me. Another, a top expert on libel, said: “If you don’t win your case, defamation law in California is dead.” But as the Times’ lawyer kept saying in court, “the quote/unquote truth doesn’t matter.” She was right. What mattered were power, money and influence. Judges in LA, many of whom are former prosecutors, are loathe to anger either the LAPD or the LA Times. This ruling means my case will probably never go to trial. The court has already ordered me to pay $330,000 to the Times for their legal fees because hey, a guy with $7 billion obviously needs and deserves to get cash from a cartoonist the Times used to pay $300 a week. That sum will definitely be higher—perhaps double—by the time the Times files the rest of its padded legal fees. (If I had won at this stage, the Times would not have owed me anything and I would have been responsible for my own legal fees. Nice system.) I will never get discovery, which means neither I nor the readers of the Times will ever learn the details about how then-publisher Austin Beutner (now superintendent of LA schools, where teachers are on strike because Beutner doesn’t want to give them a proper raise) arranged for the LAPD pension fund to become Number One shareholder of the Times’ parent company. Neither I nor the readers of the Times will ever know just how deep the corruption between the LA Times and the LAPD went, or to what extent the Times agreed to provide police-friendly coverage. For me personally the ruling necessarily means bankruptcy and/or being forced to leave the United States so I can continue to earn a living. This is because, as a self-employed cartoonist, my bank account can be frozen so everything I deposit goes to the Times. I would not be able to eat. This used to be the kind of thing that happened to journalists in other countries, not the U.S. Unfortunately, I couldn’t even get the ACLU behind me—because they don’t want to be seen as opposing the anti-SLAPP law. Several First Amendment organizations and media outlets told me they were sympathetic to my plight but would not do anything that seemed to oppose anti-SLAPP. I should note, we did not challenge the anti-SLAPP law. We pointed out that it did not apply to me. [But the Times lawyer filed for anti-SLAPP protection anyhow.] I’m much luckier than the murdered Jamal Khashoggi—though the scorched-earth litigation tactics and lies deployed by National Enquirer/LA Times attorney Kelli Sager makes me pretty sure the Times would do the same thing to me if they thought they could get away with it. But the court’s and the LA Times’ real message isn’t directed toward me. What the court did in brazen deference to the LAPD and the LA Times and in direct opposition of the law was to send a message to journalists in California: do not mess with the cops and do not mess with a newspaper owned by the cops. If you do your jobs, we will crush you. At a time when reporters who still get to work are grateful to merely see their salaries slashed rather than join the ranks of the unemployed, you’d have to be a total goddamned idiot to criticize law enforcement. There is one last slim reed of hope: the California Supreme Court. I am petitioning the high court to reverse the Court of Appeal’s anti-SLAPP ruling. But the odds are long. They hear fewer than five percent of appeals. Help spread the word! RCH Final Note. We don’t need to know the finer points of anti-SLAPP law in order to understand that Rall is being fucked. He asks for it. He’s a rabble-rousing trouble-maker. As you can plainly see. But he doesn’t deserve this. Here’s hoping there’s justice somewhere in the California legal system.

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

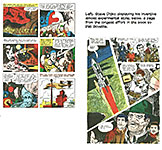

Terms and Conditions: The Graphic Novel By R. Sikoryak 108 6x9-inch pages, color; 2017 Drawn & Quarterly paperback, $14.95 SIKORYAK’s UP TO HIS OLD TRICK, imitating famous cartoonists. Each of the book’s 96 content pages is drawn in the style of a different cartoonist—some syndicated comic strip cartoonists, some comic book cartoonists—and each features a different, usually well-known character. The speech balloons and caption blocks are filled with text—the complete text of the iTunes Terms and Conditions as of September 17, 2014. Hereabouts are samples of a few of the pages.

As a rule, the visuals are not related to the text at all. Says Sikoryak: “I would occasionally shuffle the order of the drawn pages to allow for some interesting juxtaposition of word and image, but generally any connection between the two is complete happenstance.” There seems to be a central character—a bespectacled guy with a five o’clock shadow. Perhaps a self-caricature of Sikoryak. He shows up on almost every page. Or at least his five o’clock shadow does, adorning whatever character is featured on that page. Snoopy with a five o’clock shadow. On every other page, this Sikoryak character is drawn in a more-or-less realistic manner (sometimes wearing superhero tights); on alternate pages, he’s a cartoony character. You’d think with this thread of seeming continuity, there’d be a story. But, no. After reading a few of these pages and discerning that no story connected the pages—no narrative—I gave up, and turned pages, jotting down the names of the cartoonists and comics Sikoryak was imitating: Snoopy, Popeye, Dick Tracy, Little Lulu, Nemo in Slumberland, Archie, Garfield, Pogo, Smurfs, Nancy, Snuffy Smith, Cathy, Dennis the Menace, Beetle Bailey, Felix the Cat, Tintin (with a black dog), Prince Valiant, Family Circus, Brenda Starr, Hogarth’s Tarzan, Edward Gorey, Scott McCloud, Roz Chast. Even Jeff Smith’s Bone. Sikoryak says this tome is a homage to all these cartoonists (and dozens more I didn’t name). He lists the cartoonists and the specific works he’s homaging at the end of the book, which is not, as you have by now ascertained, a graphic novel despite its subtitle. Although no narrative connects the pages, you’d think that if you ignore the text (which has no relationship to the pictures), the pictures on each page are somehow a stand-alone pantomime featuring the character of the moment. Nope. None that I could see. So what is this book about? Why does it exist? It exists because Sikoryak enjoys imitating the work and/or stylistic mannerisms of other cartoonists. That’s it. Self-indulgent maybe, but all artists are essentially self-indulgent personalities. To the extent that we enjoy watching someone perform, the book, a bravura performance, is still just a pleasant diversion. Otherwise, it serves no purpose. But do our entertainments need some other purpose?

The Unknown Anti-War Comics: Featuring the Art of Steve Ditko Edited by Craig Yoe; Introduction by Nate Powell of March; Foreword by Noel Paul Stookey of “Peter, Paul & Mary” 224 8x11-inch pages, color; 2018 Yoe Books IDW Publishing hardcover, $29.99 SLIGHTLY MORE THAN THREE DOZEN Charlton anti-war comics stories from mid-1950s and 1960s are collected here, beginning with four tales from Never Again Nos.1 and 8, the first anti-war comic (which appeared only in these two nonchronologically numbered issues). The work of 15 artists includes eight stories by Ditko, but Bill Molno drew the most, 12, and Ross Andu, Charles Nicholas and Rocco “Rocke” Mastroserio are also represented almost as often as Ditko. In his 11-page essay, Yoe rehearses the history of war and anti-war comics, observing that while crime and horror comics were severely restricted by the Comics Code of 1954, war comics were not scrutinized, “yet there is nothing more horrific or criminal than war” and “war comics, with their de facto acceptance of conflict as a solution, were printed in droves, programming malleable minds that war is ‘exciting.’” Yoe has been involved with anti-war efforts since 1969 when he and Paul Mavrides produced an underground newspaper when in high school. There, he started a school club called War Resisters League, and while in college at the University of Akron, he organized anti-war protests. In his essay, Yoe quotes approvingly former general Dwight D. Eisenhower, who, while president of the U.S., was promoting “space for all mankind” and “space for peace,” writing: “Let us this time, and in time, make the right choice, the peaceful choice.” Observing that powerful weapons were being developed for possible use in space “which will greatly increase the capacity of the human race to destroy itself,” Ike went on: “Can we not stop the production of such weapons? ... Should not outer space be dedicated to the peaceful uses of mankind and denied to the purposes of war?” “I like Ike,” Yoe says, finishing this segment of his essay by intoning Eisenhower’s presidential campaign slogan. The stories, set in medieval as well as modern times and the future in space, are ironic parables that advocate against war and for peace with O. Henry twist endings. In Never Again, one story traces the history of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce tribe, who sought in the 1800s to avoid war with invading white legions by leading his people into Canada. Ultimately, Joseph failed to reach this haven. Exhausted by the thousand-mile trek, Joseph surrendered, saying, memorably, “I will fight no more, forever.” Another Never Again tale takes place during the notorious Hundred Years War between France and England, 1340-1450. At the battle of Crecy, the British won because they deployed, for the first time in battle, the long bow, which was powerful enough to send lethal arrows over the heads of advancing French infantry to destroy the cavalry behind them. A wounded English soldier is convinced that the long bow will prove invincible and therefore will end war forever. In another story, an old veteran sailor explains that he kept re-enlisting after World War I because each successive conflict he thought would be the last. World War I is represented in a story about two pilots, a German and an Englishman, who meet in the skies, knowing only one will be victorious. Most of the stories, however, are in the category of science fiction from such Charlton titles as Strange Suspense, Mysteries sof Unexplained Worlds, Space Adventure, Out of This World, Unusual Tales and the like. Each story proves the error of human ways over and over again, as representatives of Earth resort to violence: they think they are protecting their civilization but they’re unknowingly killing peaceful aliens. In one story, humans build a wall around an alien space ship, thinking that by confining the aliens, Earth will be safe. A delusion that persists even today. Pat Boyette draws the book’s longest tale, a multi-part story about a doomsday machine, which, set to destroy Earth if any atomic activity is detected, is almost inadvertently set off when an atomic-powered space vehicle returns to Earth from a long deployment in space, looking for survivors on Earth. Yoe offers a fragment of broader comics history when he reports that Charlton was formed by John Santangelo and Ed Levy, who met while serving time in jail for relatively innocuous crimes—copyright violation and “some white collar crime.” The artwork in these usually overlooked books is excellent—sturdy, workmanlike visual storytelling by people who can draw well. And do, as we can tell from the sample pages posted herewith. Charlton may not have paid artists well, but some pretty good artists plied their trade in the paycheck cellar.

IRKS & CROTCHETS Those who have the time to study such things claim that the most difficult small object to flush down a toilet is a ping-pong ball.—ReMind

INTERLUDE Assuming that by now, if you’re not already a $ubscriber, you’re persuaded and want to subscribe, we interrupt with this commercial appeal—:

SUBSCRIBE TODAY! Just $3.95/quarter after $3.95 introductory month To subscribe, return to the home page and click where it says Click Here at the top of the page, center. (Don’t click where it says Subscribe; that will just put you on our mailing list to receive notices of fresh postings; you’ll get those by Clicking Here and subscribing.

And now we return to our regular programming with our customary assessment of the state of the art of single-panel cartooning —:

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO Single Panel Magazine Cartooning In Esquire, The New Yorker, Playboy and Wherever Else IT SOUNDED SO PROMISING AT THE TIME. We rubbed our hands in silent glee. Just as the Cadillac of single-panel cartooning (Playboy) was being put up on blocks, shutting down the genre’s most celebrated venue, Bob Mankoff, for 20 years cartoon editor at The New Yorker, decided that his leaving that magazine at the end of April 2017 was not, after all, his retirement. Barely had the dust settled in the office he just vacated than he found another office, at Esquire, where he’d be humor and cartoon editor. Mankoff promised to enjoy his new job by revitalizing magazine cartooning. He was going to edit differently. Instead of waiting for cartoonists to submit their wares for his consideration, he’d reach out and work with individual cartoonists, perhaps a different one for every issue. He’d pick a theme for the issue, then see what a selection of cartoonists might do with the idea, helping them along, suggesting and hinting and prodding. The first couple issues of Esquire under his cartoon guidance resulted in a couple of full-page color cartoons (see Opus 370b), and so I had hope that Esquire and Mankoff would, as advertised, revive the most sumptuous expression of the single panel cartoon in its full-page, full color glory. Alas, it was not to be. After a couple more issues with a couple more full-pagers in color, Esquire sank to its new depths. Each issue had a couple tiny wordless cartoons by Seth Fleishman scattered through the opening departments and a full-page “essay” cartoon as the magazine’s last page. But no re-birth. Mankoff had promised to nurture new talent, too. But so far—two years in—he’s using all his former shipmates at The New Yorker. Well, he knows them. He knows their capacities. It’s easier, no doubt, to work with them than with strangers. Fleishman has been back every issue since his debut. And he’s in the one at hand, too—March’s issue.

One of the other New Yorker regulars Mankoff has chosen to work with is cartoonist Drew Dernavich. For Esquire, Dernavich (or Dd as he signs his cartoons) produces a column in the opening pages. Entitled “Esquipedia,” it dwells at some length (a column’s worth) on a topic dealt with more exhaustively elsewhere in the issue. For this issue, it’s cars, as you can see in the foregoing visual aid. Dernavich produces a paragraph or so of sardonic text, illustrated with drawings or photos or his own cartoons. The same impulse toward humor finds expression in the re-emergence (with Mankoff’s arrival in 2017) of “Esky,” the goggle-eyed roue with a moustache. He shows up in 2 or 3 spot illos, accompanied by some text,

entitled “Eskpertise.” For at least two previous issues, Mankoff, apparently at a loss for cartoonists who are willing to jump through his hoops, has chosen to publish one of his own cartoons. He does so again in this issue.

And finally—as usual—the last page in the issue is what we might call an “essay cartoon,” a sort of sequential array of images offering a telling insight into what we’ve all become.This issue, we find out about “evolution.” Its illustrator is Edward Steed, another New Yorker cartoonist (who, in this issue, also supplies a full-page illustration for an article on popular watering holes in Washington, D.C.).

The Ante-Mankoff Esquire IT’S PRETTY CLEAR that the revolution in magazine cartooning that Mankoff’s arrival at Esquire was heralding hasn’t arrived. Well, the essay cartoon is a nice gesture in the right direction, but this format isn’t numerous enough —or powerful enough— to constitute a “revolution” of any dimension. I’ve wondered what Esquire was like before Mankoff, and a couple weeks ago, I chanced upon an issue from January 2014, which, I thought, might offer a solution to my puzzling. It did. Nothing spectacular. Under the previous editor, David Granger, who worked without a cartoon or humor editor, the magazine, unsurprisingly, had no cartoons. None. Not even the tiny equivalent of a Fleishman illo. So at least Mankoff’s presence on the masthead has resulted in some improvement (speaking, as we always do, from the perspective of a cartooning afficionado). Esky was also absent from Granger’s Esquire. The

pages, however, were crowded with vaguely comical scatterings of the sort we

find at the bottom of the page I’ve posted near here. There are other pages somewhat like this in the issue. None with cartoon illustrations, but several with humorous “footnotes” like we see here. While none of this guarded effusion is the same as single-panel cartoons, it nonetheless shows that Esquire of recent yore realized that humor had a place in the magazine. Granger didn’t go so far as to publish cartoons in recognition of the magazine’s historic role, but he sensed something. And the current editor, Jay Fielden, sensed the same thing and gave in to his instincts in hiring Mankoff. From my perspective (that of the ravening cartoon afficionadeo), neither Fielden nor Mankoff has gone far enough. Yet. But we have hope. Eternally. Giving comfort to the hope is Mankoff. He’s not just a cartoonist. Not just an editor. He’s also a stand-up comedian. He’s always in search of a wise crack. And when he finds one, he utters it.

THE COVER STORY on the current (March) issue of Esquire is about “an American boy,” a 17-year-old white kid and “what it’s like to grow up white, middle class, and male in the era of social media, school shootings, toxic masculinity, #MeToo, and a divided country.” Makes you wonder. What’s the audience for Esquire these days? Who do the editors think buys the magazine? In the beginning, the buyers/readers were mostly male. The focus was on men’s fashions. But from the very first issue (in October 1933), George Petty’s leggy pin-ups were part of the content; and they continued in that role until 1956. The magazine also had literary pretensions, which it exercised with great success for at least its first two decades. Now? Who’s reading “an American boy”? Concerned parents?

The New Yorker Anniversary Cover AND THAT BRINGS US, as usual in our regular review of gag cartooning, to The New Yorker, perhaps the only remaining viable venue for the genre. Before getting to an examination of the magazine’s cartoons lately, we pause in recognition of its 94th anniversary. Founding editor Harold Ross’s magazine celebrated every anniversary by publishing, again, the cover of its first issue, February 21, 1925. It was drawn by Rea Irvin, who was “acting” as “art director” for Ross (who hated the formality of titles). Irvin had prepared the layout for the first issue and designed the distinctive typeface for the magazine, modifying a face developed by Carl Purington Rollins. He also drew most of the department headings, including, for the first section of the magazine (called, initially, Of All Things), a monocled Regency-era scribe in a high collar with his nose in the air. The same personage is shown gazing through his monocle at an assortment of thespian caricatures for the Theatre department. Irvin drew the first issue’s cover almost by accident. Ross dithered about picking a cover image, and at the last minute before the printer’s deadline, he turned to Irvin, which didn’t give the artist much time. Desperate, Irvin went back to his files for the pictures that had inspired the 19th century dandy that headed two of the magazine’s departments. Since the character appeared twice in the first issue already, why not on the cover too? He turned again to an 1834 caricature of the Comte Alfred d’Orsay at the height of his stylish influence. Irvin added a monocle to signify supercilious intellect and a butterfly for whimsey, producing an elegant emblem of insouciant detachment. Irvin’s picture was perfect. The perfect portrait of a seeming sophisticated man-about-town who is so vapidly empty-headed as to find a fluttering insect an object worthy of minute inspection. What prospective first-time reader-buyers thought of this incongruous picture when they saw it on the newsstand, we can’t, with authority, say. They were no doubt baffled by the image of a man dressed in the height of 19th century fashion covering what purported to be a magazine of contemporary jazz age sophistication and wit. But what they thought was irrelevant. Ross loved the drawing. Despite the time-warped attire, Irvin’s picture of a would-be sophisticate gently ridiculed the very people the magazine aimed to appeal to, embodying exactly Ross’s intention. Irvin’s dandy set the tone and intent for everything that followed—within the first issue and all subsequent issues. Ross always said Irvin’s cover was the best thing in the first issue. It was so apt an emblem for the magazine that no one could ever think of a suitable sequel to use for the ensuing anniversary issues. In fact, until the first anniversary issue in 1926, probably no one had given any thought to anniversary issues. That the magazine had survived a year since its debut, running deeply into the red, was miraculous, so to celebrate the miracle, Ross and his cohorts no doubt decided to repeat the cover image of the first issue as a gesture of defiant triumph—“Look at me! I’m still here, snooty and distant as ever.” Perhaps for substantially the same reason, Ross repeated the cover again on The New Yorker’s second anniversary and then the third, by which time, the magazine was running a little in the black. The habit was formed. Thereafter, Ross ran the same cover every year on the last issue in February. And until the advent of Tina Brown, Ross's successors did the same in honor of the founder (and of Irvin). So Irvin's haughty dandy, anachronistically attired in top hat and high collar, graced the cover of America’s most urbane weekly magazine once a year for 69 years. When the anniversary approached in 1993, Tina Brown was editor, and she opted out of the tradition, and for the first time, Irvin’s boulevardier wasn’t on the anniversary issue’s cover. Sort of. Instead, she used a picture by Robert Crumb, who drew a modern, slacker version of Irvin’s dandy. For the whole story of Irvin’s character, visit Harv’s Hindsight for March 2015, a history of Eustace Tilley, the name eventually attached to the Irvin dandy.

This year, the re-interpretation is only a faint echo of Irvin—a woman, perhaps a South Sea islander, looking through lorgnette, with a butterfly in the wallpaper behind her.Only those cognizanti steeped in the history of The New Yorker will recognize the imitation. This year’s anniversary cover appears at the upper left on the adjacent visual aid; the originating Irvin dandy is at the upper right. And below, two recent echoes of Irvin—for 2017 ands 2018. The last time Eustace Tilley showed up for the anniversary was 2011. Alas, the new tradition is whittling away at the old. It is ever thus. Kadir Nelson, the artist for this year’s commemorative, chose his partner, Jungmiwha Bullock, to model for him. Her name, part of which means “beautiful flower,” is echoed in the title of the cover, “Spring Blossoms.” Nelson says he “wanted to portray a beautiful, elegant woman who would command your attention at the opera” (hence the lorgnette). The opera, of course, has little to do with The New Yorker or vice versa. But a beautiful elegant woman is never out of place on the cover of a newsstand publication. That she’s a black woman is but another of the magazine’s continuing effort (via art director Francoise Mouly) to use images of black people on its covers—especially on the anniversary issue, which always comes during Black History Month. Alas, as Kim O’Conner points out at slate.com, the covers are but “an empty avatar of change, which is different from change itself.” “The New Yorker loves to put black women on its covers,” reads O’Conner’s headline, “but black women still don’t draw them.” Of the 60 covers since the 2016 Election, “fully half are drawn by white men who are 55 or older,” she goes on. “Of the 34 artists whose work was featured during that time, only two were black—and both of them were men.” Mouly’s heart, O’Conner admits, is in the right place: “she garnered widespread praise for publishing the work of (unpaid) artists, including many women of color, in Resist!, the political magazine she curated with her daughter, Nadja Spiegelman.” Now if she can just apply that practice to The New Yorker....

New Yorker Cartoons TO RETURN, FORTHWITH, to the cartoons in The New Yorker, we encounter immediately Emma Allen, the 29-year-old woman who inherited Bob Mankoff’s job when he departed almost two years ago. Her ascension to the cartoon editor’s chair was quick: she’d been on the magazine’s staff in related roles for only about five years. She worked first in verbal humor— Shouts and Murmurs and Talk of the Town. But one of her assignments was to pick the vintage Otto Soglow spot drawings that illustration Talk so she acquired some sense of cartoon drawing. After a while, she began editing the texts. “The key to her success,” said Andrew Goldstein at his artnet.com interview of Allen, “has been her digital savvy,” which became increasingly apparent as the magazine moved to online humor with Daily Shout. “Now,” Goldstein continued, “she is poised to continue this web migration with the cartoons.” Eg.: Daily Cartoon. Allen

likes long form cartooning—comic strips and graphic novels—and wants to move

into animation, affections and aspirations that seem suited to expression on

the Web. The Daily Cartoon has occasionally offered multi-panel

cartoons, and once, she bought a 4-page cartoon for the print magazine: as we

can see in the one-page extract nearby, it looked very much like an excerpt

from a comic book. While she would like to do more animated stuff, she likes “the gag cartoon’s purity,” she said. “It’s the lost art of distillation. Conveying a complex joke in a compact format, sometimes without even a caption. Part of the joy of the cartoon is its format exactly as it is. So as much as I have grand plans to do longer comic stuff [the classic multipanel comic strip], and videos, and definitely animated videos online with cartoonists, I’m also as beholden to preserving the gag style in some version of what it is. “The cartoon in The New Yorker sense doesn’t really exist any other place in the world,” she concludes. “We’re pretty much the only game in town.” Online,

the only game is usually played with single-panel cartoons on topical matters—current

events and the ever-enjoyable Trumpet’s buffoonery as we can see in the samples

collected near here. And because they are topical, they suffer little of the

surreal whimsey that so appeals to Allen. The online feature allows the magazine to be “hyper-responsive” to current events, “particularly important when ‘there’s just so much to respond to and satirize in the world of politics’”Allen said in an interview with Elizabeth Breiner at floodmagazine.com. It’s “a balancing act mediating the imperative to ‘lampoon people in power’ and simply offer readers a reprieve from it all,” Breiner said, quoting Allen. She likes “observational humor,” Allen told Goldstein. “Rather than generating my own comedic fodder,” she says, “I like to keep an eye out for what is funny in what’s going on around me.” She learned from doing Shouts that “the things that are funniest defy the rules.” By which, she means things that surprise. And that, of course, is true. Single panel cartoons, which I’ve called the haiku of cartooning because of their compression, consist of a picture that’s a puzzle and a caption that explains the puzzle. Our surprise in realizing how the puzzle works makes us laugh. But judging from what Allen says about cartoons, I don’t think she sees cartoon captions as springing the surprise on a viewer of the picture (or vice versa). In other words, she doesn’t really understand how cartoons work. For her, it’s still something of a mystery: “Cartoons have this weird alchemical combination of pleasing drawing and jokes—they’re like the ur meme,” she said. She

sees cartoons as “weird lyrical drawings”—“pretty pictures” almost. In other

words, she appreciates the graphic artistry of the cartoon. That’s nice, but it

doesn’t explain the choices she makes in the cartoons she publishes, some of

which feature ugly nearly incompetent drawing that is barely tolerable in a

visual medium. She told Breiner that the essential categories for the classic gags are “gimlet-eyed observational things” and “things that are just totally dada and surreal and come from the minds of madmen.” Said Allen: “I think a lot of people enjoy the fact that New Yorker cartoons are embedded within articles that are so bleak and grim.” Cartoons offer readers a break from the surrounding seriousness of the text they’re embedded in. Well, maybe. But Goldstein reminds us that “it’s an article of faith in literary circles that the proper way to read The New Yorker is to start with the cartoons. ... These cartoons— cosmopolitan, sly, absurdist and sometimes obscure—have been a treasured part of America’s visual culture.”

ALLEN AND HER ASSISTANT, Colin Stokes, look at about a thousand submissions every week, and by a process of elimination, reduce the stack to about 100. Then Allen looks at those cartoons and winnows the stack to about 60, from which New Yorker editor David Remnick picks 15-20 for the next issue. The “process of elimination” seems to be mostly whether a cartoon makes Allen and Stokes laugh. So it all comes down to the editors’ comedic sensibilities. Sometimes the chosen cartoons are in the classic manner; sometimes, in a more surreal manner. Sometimes, as Allen says, the cartoons are simply pictorial breaks from the bleakness of the surrounding text. The

first cartoon in our first visual aid seems to be in the classic mold. No.3 is either an example of Allen’s observational sense or her tendency to enjoy surreal silliness. No.4

in our next visual aid is another example of silliness. A “staycation,” I gather, is when you stay at home when vacationing. So Gulliver just stays strapped to the ground in a prone position and spends his time eating chips and watching re-runs of “Seinfeld”? Okay. Surreal.

No.9 must be one of Allen’s observational fantasies. Just another break in the otherwise sullen gray surroundings of text.

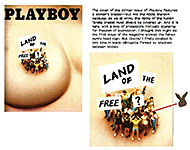

And Then At the Rabbit Hutch OVER AT PLAYBOY, the “winter” (not January/February) issue is celebrating the magazine’s 65th anniversary. Unlike at The New Yorker, the Playboy festivities

are all-out and full-blown and conspicuous instead of discrete—including, most

particularly, the cover, which features, notably, the nipple on a female

breast. Or, rather, in place of the nipple—covering it up—is a small crowd of persons carrying signs that proclaim “the land of the free?” with a question mark. The question mark accents the theme of this issue—is freedom of expression absolute in our country? “The censored nipple functions as the poster child for a much broader problem of social injustice, and our protestors want to know: Is this really the land of the free?” The issue celebrates free speech—an apropos and vital rite in the country of the Trumpet, who thinks the news media is the enemy of the people, who need to be protected by shutting off the free flow of ideas. Just last night (Sunday, February 18), I read a press release reporting that the Trumpet is thinking of launching an investigation into “Saturday Night Live” because of Alec Baldwin’s irreverent impersonation of the Prez making his “national emergency” announcement on the previous Friday. The threat is alive and well. The question mark on the cover proclaims the irony of Playboy stumping for free expression: the nipple on the female bosom must, at all cost, be covered up and never bared in public. Even, ironically, at the cost of freedom of expression on Playboy’s cover for an issue devoted to free speech. But all is not lost. Just up the road from Rancid Raves Denver HQ, at Fort Collins, Colorado, signs of hope have emerged—: On Saturday, February 16, the venerable Denver Post reported on a recent triumph of “Free the Nipple-Fort Collins.” FTNFC has been campaigning against a city ordinance that prohibits women from baring their breasts below the areola but says nothing about men baring their breasts, areolas and nipples and all. FTNFC sued the city in federal court, claiming the ordinance violates the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. On Friday, February 15, the 10th U.S. Court of Appeals agreed, upholding a lower court’s injunction that prohibits Fort Collins from enforcing a nudity ban that criminalizes the act of women going topless in public. What’s next? If Playboy has its way, presumably buttocks will be next to be unveiled in public in support of freedom of expression. (Playboy has shown a marked preference for photographs of naked female butts under the new management with Hugh Hefner’s son, Cooper, running the “creative” department.) For a more rambling discussion of the role of repression in the life of the nipple, refer to Harv’s Hindsight for July 2014. The “winter” issue examines free speech in a number of ways. It offers a short article about Lenny Bruce, champion of free speech who ultimately paid with his life for his exercise of it in nightclubs around the nation. And we have a short article about Stormy Daniels and her crusade (accompanied by several b/w photos, one of which bares her impressive chest that precedes her into any room she enters by at least ten minutes). Ezra Miller gets a 7-page pictorial, demonstrating that Playboy isn’t old fashioned about sexuality and is willing to turn a gay, bisexual man into a pin-up. And a page of “talk dirty” quotes completes the crusade. (Did you know that the 14th century is the widely accepted date of the first publication of the word fuck? And that “fuck Trump” was bleeped by CBS from Robert De Niro’s acceptance speech at the Tony Awards? And that “cum” is not a word?) Other novelties litter the anniversary event. LeRoy Neiman’s femlin has been replaced on the Party Jokes page. A long lost interview with Maya Angelou appears, at last. And many of the Playboy Rabbit’s appearances over the years, within and outside of the magazine, are recorded. The magazine boasts three gatefold Playmates—and each involves a novelty: the photographic gatefold is backed by a painted version of the same Playmate by Maly Siri.

But cartoons? Alas, as we’ve observed before, the once glorious full-page color cartoon is all but gone. This issue includes three cartoons by two New Yorker cartoonists—two by Christopher Weyant (who’s also dabbling in editorial cartooning lately) and one by Tom Toro, plus the ever-present Nicholas Gurewitch, whose work represents the “new” Playboy cartoon—simple linework that is then colored as if it were a page in a coloring book.

Gone are the great painterly achievements of those who followed the incomparable Jack Cole—Eric Sokol, Doug Sneyd, Buck Brown, Kiraz, Roy Raymonde, and, above all, Eldon Dedini. In what can only be a feeble attempt to resurrect its status in the cartooning world, this issue publishes a 6-page comic strip— Eric Powell’s The Goon, in color in a Playboy-related romp entitled “The Maltese Bunny.” But the rabbit in question is not black: it’s brown—chocolate, and The Goon takes a big bite. (The only Maltese black bunny we’ve seen in this issue is, as we noted, on the cover.) Some of the cartoons of the fabulous yore appear on two pages in the “heritage” department of the magazine at the back of the book. But this issue’s sampling includes only one of the watercolor masterpieces of yesteryear—as if by including them the extent of the present lapse in cartoon art is made more evident; and so, all the rest, b/w line art. Makes me weep.

Elsewhere IN THE ABSENCE

OF GOOD PLAYBOY CARTOONS, we’ll pause at a collection of miscellaneous

gag cartoons that I’ve harvested from various places, all obscure. They attest

to the enduring life of the art form even as venues for it evaporate. The examples now before you delighted me. In every case, the caption explains the picture surprisingly, astonishingly—absurdly. At the lower left, the work of Bob Vojtko (pronounced voit-ko) always grabs me: I love his stark simplicity. Like almost all of those whose work we see, Vojtko is a part-time cartoonist: no one can make a living in this bleak field of magazine cartooning any more. Full-time, he works in a grocery store, where he’s been for nearly four decades. We’ll end this tirade with a few more of his cartoons.

Yeh, I know: some of the cartoons don’t have captions: they’re just pictures. But in Vojtko’s hands, the pictures alone are uproariously funny. Incidently,

back in the mid 1980s, Vojtko teamed with writer Richard O’Brien to

produce a comic strip about a pre-adolescent girl named Suzy. Unhappily,

they were unable Too bad. The drawing was unique, as all of Vojtko is, although not quite as fuss-free as most of his magazine cartoons are.Suzy has been reprinted (or “collected”) in book form by Ramble House in 2007; it can be found online.

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status

Dry Country By Rich Tommaso 136 6x10-inch pages, color; 2018 Image paperback, $16.99 THE COVER OF THIS graphic novel bristles with subtitles—“A Lou Rossi Novel,” “The Everyman Comic Series”—but I don’t know that there’s another Lou Rossi novel anywhere. In this book, Lou Rossi is a Generation X slacker—“out of step with the rave culture of Miami, 1990.” He’s a freelance cartoonist/artist, a “21-year-old virgin” who aspires to meet the female of the species. And he finally does in Janet Laughton. They start dating, and then she disappears. The rest of the book is Lou being an amateur detective, trying to find Janet. It’s pretty much a procedural narrative—Lou unearthing a clue, then following it until it plays out. “There are some obvious suspects,” the back cover blurb tells us, “—in the form of not one but two crazy ex-boyfriends” and “a mysterious yellow VW bug filled with four drunken blonde girls.”

The book proves you can produce a credibly serious story with drawings that are painfully simple.But Lou has too many male friends, who, although looking different, “sound” the same: Joe, Earl, Eddie, Rob, Cliff. I read the book in a single sitting, but by the end, I couldn’t remember who Joey was or who the guy is who came to visit him in the hospital, where he’s recovering from some violent encounter. Was he shot? Beat up? Dunno. But Joey remembers who did it to him: a tall guy with long black hair. And we subsequently see that guy getting shot by two other unnamed guys looking like FBI agents, who call him Clifford. Who is this long-haired guy and what is his connection to Janet? Or to the four blondes? Dunno.