|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 374,

Part One (December 22,

2017). It’s Christmas. The Christians were very smart in establishing their

religion with the birth of a baby. Everyone loves a baby. But the picture of

Christ that I like is called “The Laughing Jesus.” Why Part One, you query? Where’s Part Two? It’s all because I get carried away verbally and before I knew it, I’d rambled up a posting that is simply too long for anyone to read. I did it before recently—Opus 370, at the end of August. Well, I’ve done it again. So I’ve chopped the extravaganza into two tidy, readable pieces. The first of those commences forthwith. As is our custom at this time of year, we’ve assembled book reviews as a kind of shopping list so you’ll know how to spend the money Aunt Sarah gave you for Christmas. They’re all listed below in the usual departments. In addition, we have a long article on the verdict in the infamous “comic con” trials (is the term generic or is it owned by Sandy Eggo?), a farewell to the New York Mad, a discussion of a conservative “rogue” ediltoonist on the Web, and the usual array of news, plus analysis of newspaper funnies and a savory tidbit of lost comic strip history. Next time—Opus 374, Part Two—will offer a raft of editoons on Ray Moore, Trumpian antics, and sexual harassment, which last is the subject of a lengthy seminar on the subject. You should get it before New Year’s, our gesture at summing up the year without actually summing it up at all. Next,

our anyule greeting, after which, promptly without delay, a list of what’s

here, in order by department. But first, the anyule greeting.

NOUS R US Star Wars Last Jedi Big Box Office Sandy Eggo Gets Comic-Con Exclusively Marvel Covers Vanity Fair Censorship Still Lurks Tom Richmond’s Mad Farewell Cartoonists Raise Money for Hurricane Survivors Disney Buys Fox

ODDS & ADDENDA Bill Finger Gets a Street in the Bronx New Wimpy Kid Marvel to Launch New Animation Series Warner Bros Shakes Up DC Movie Management Time, Inc. Sold to Family Circle

EDITOONERY Conservative Rogue Editoonist on the Web

THE FROTH ESTATE Fake News The Orwellian State of the Trumpet

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Sampling the Unusual and Verboten in the Funnies

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: Babes in Arms: Women in the Comics During WWII Terry and the Pirates by George Wunder, Vol. 2 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons The Bible by Joe Kubert and Nestor Redondo

BOOK REVIEWS Longer Critiques Of—: Oh My God—They Printed That?! Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, Vol. 5 Blitt (cover artist for The New Yorker)

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Graphic Novels—: The Man Who Laughs The Man from the Great North by Hugo Pratt Calamity Jane (biography)

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE The Long-lost Last Li’l Abner Strip

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi scored the second best weekend opening of all time (not adjusted for inflation) with a $220 million bow over December 15-17, reports ICv2, adding that the figure represents a mammoth 80% of the money spent on movie tickets in North America during those three days. While this weekend’s box office total represents a 228% increase over the same weekend last year when Moana topped the charts for a third time, a better comparison would be to the next week in 2016 when Star Wars: Rogue One opened, which would yield a 25% lift for The Last Jedi. This boost is important since, despite a strong November, at the beginning of December the box office was still down 4.4% from 2016. The Last Jedi is only the fourth film to open with more than $200 million. Star Wars: The Force Awakens still leads the pack with $247.9 million, while the only other films to open in that rarefied air are Jurassic World ($208.8 million), and The Avengers ($207.4 million).

SAN DIEGO SECURES ITS EXCLUSIVE USE OF “COMIC-CON” Salt Lake City Loses in Court In a ruling with wide-ranging implications for the multi-billion dollar fan events industry, a jury in San Diego today decided in favor of Comic-Con International (CCI) in its long-running battle with Dan Farr Productions and Bryan Brandenburg, organizers of Salt Lake City Comic Con, over the use of the term "comic con" (or comic convention) as a descriptor for a pop culture fan event. The jury decided that the Comic Con mark is valid, reported Rob Salkowitz, and that Salt Lake City used it in a way likely to cause confusion to customers. SDCC was asking for $12 million in damages, but the jury awarded only $20,000 for corrective advertising because they found the infringement not to be intentional. In upholding the trademark, the Court ruling allows SDCC to seek licensing agreements with over 140 events in the US that call themselves comic conventions, or else require those events to rebrand. Excerpts from Salkowitz’s report follow—: The case of Comic-Con vs. Comic Con has been seething in the background since 2014, when promotional actions taken by the Salt Lake City convention, including driving a SLCC-branded vehicle through the streets of San Diego during Comic-Con, prompted CCI to issue a stern “cease-and-desist” letter to Dan Farr Productions, claiming they were seeking to deliberately create confusion between the two events. Farr and Brandenburg protested that the term “comic con” was generic, and that CCI’s trademark applied only to “Comic-Con” (with a hyphen). They pointed to numerous examples of fan events calling themselves comic conventions as evidence that CCI either did not own the mark as they claimed or was so inattentive to enforcement and licensing that they could not legally single out SLCC in this case. As evidence, they cited examples of use of the term “comic con” to describe events that took place prior to the first San Diego event in 1970, and a case where CCI had withdrawn its application for a trademark on the term “Comic Con” (no hyphen) in the early 2000s. Farr and Brandenburg saw advantages in taking their case public, rallying fans to the idea that “comic con” belongs to everyone, not one particular institution. They ran a coordinated campaign on social media including promoted Facebook posts, marshalling an online army of supporters to comment, upvote and retweet their position and paint themselves as altruistic “Davids” standing up to the “Goliath” of SDCC, which is seen by some as the embodiment of commercialism and Hollywood hype. It was disclosed in court proceedings that the two organizers voted themselves bonuses of $225,000 each as they were mounting a crowdfunding campaign to get fans to pony up for their legal defense. However, the comment threads on SLCC’s posted content indicated that the tactics were effective in mobilizing fan anger.

CCI, MEANWHILE, SAVED ITS BEST LINES FOR THE COURT, wrote Salkowitz. They asserted that Comic-Con was a brand recognized to apply exclusively to the San Diego show, and offered in evidence a survey showing that more than 70% of respondents agreed. The validity of the survey was called into question by SLCC attorneys during the trial but the jury appeared to accept it as proof. In filings seeking summary judgment, Comic-Con produced emails and public statements by Farr and Brandenburg boasting of how they sought to “hijack” the media notoriety of SDCC to boost their own event. There are dozens of events around the US calling themselves some variation of “Comic Con,” including several large independent shows in Phoenix and Denver, and, significantly, the 180,000-plus attendance New York Comic Con and 80,000-plus attendance Emerald City ComiCon, both run by events promoter ReedPop. With the trademark now officially upheld in Federal Court as a result of the action taken against SLCC, all of them will now potentially need to obtain license from CCI to use the term, or else rename their events. The SLCC organizers pledged to appeal the decision prior to the verdict. The verdict, which stands as settled law for the time being, means no one can now claim ignorance or ambiguity about this matter. Future cases will certainly be treated by the courts as willful infringement, with statutory damages awarded for each established case. That is, every time the name “comic con” appears on an advertisement, piece of marketing collateral, or ticket. That can add up fast. So where does that leave the 140 or so events in the US that use a version of “Comic Con” in their brand identity? Ace Entertainment, the new convention organization started by former Wizard World founders Gareb and Stephen Shamus, opted to call their events Comic Cons despite the pending litigation. Independent shows Denver Comic Con and Phoenix Comic Con each sided with SLCC in the trial, offering depositions and testimony in support of Farr and Brandenburg’s claim that the term was generic. Fan sentiment online, and informal opinions expressed by other independent show operators still heavily favors this point of view in spite of the court decision. By far the biggest questions surround ReedPOP, organizers of the massive New York Comic Con, which sold more than 180,000 tickets to its 2017 event, as well as Emerald City Comicon in Seattle, which draws over 85,000. The company has by far the greatest stake in maintaining usage of the term Comic Con for its well-established events. ReedPOP is a division of Reed Exhibitions and a part of the global publishing giant Reed Elsevier, which has vastly deeper pockets, legal resources, and more than a passing familiarity with intellectual property law. They also had a much stronger case to make. A 1964 event called New York Comic Con predates the first SDCC by half a decade, even though ReedPOP had nothing to do with that show. (For more about the 1964 event in New York, visit Harv’s Hindsight for November 2017, “The Origins and Evolution of the ‘Comic Con.’”) Reached over the weekend, Lance Fensterman, Global Head of ReedPOP, said: “We haven’t seen anything issued from the Court or the jury other than what’s appeared in the press. Until there is a final disposition of that case, we will reserve detailed comment. Nevertheless, we expect there to be no impact on our continued use of the New York Comic Con name for our annual event now well over a decade in existence.” Dan

Farr Productions, the organizers of Salt Lake Comic Con, will appeal last

week’s verdict that they infringed on the "Comic Con" trademark owned

by the organizers of San Diego Comic-Con, SLCC co-founder Bryan Brandenburg

told ICv2. The appeal will focus on limitations placed on the evidence that

SLCC was allowed to present at trial in support of their contention that the

term "Comic Con" is generic. SLCC argues that it was "permitted

to put on only a fraction of the evidence that had been developed."

Fitnoot. One of Rancid Raves’ Vast Cabal of Correspondents contributed this comment to the fray—: If I am understanding this correctly, the court decision ruled on whether Salt Lake City Comic Con violated CCI’s trademark claim as it stands, not whether it is appropriate or not. That makes sense since it would not be appropriate for a jury to rule outside of the question at hand. The question of whether "comic con" can be or should have been trademarked remains and may be tried later. The law is certainly a complicated thing! In the meantime it will be interesting to see what the Denver Comic Con and New York Comic Con decide to do. Personally, I think it is false advertising for any of them to call themselves "comic" cons since none have them have been mostly about comics for many years.

Another Footnit. Given the haphazard history of such social phenomena as comic conventions, I severely question anyone’s right to “own” the expression “comic con.” The term came into being like many linguistic occurrences. It belongs to no one, and to everyone. In short, I think it’s generic, and I suspect as this struggle goes on in the courts, legal minds will concur. Sandy Eggo can trademark their hyphenated “Comic-Con,” but that ought not prevent anyone else from using the expression “comic con” (unhyphenated, if you please).

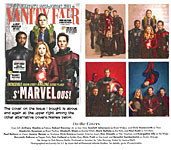

MARVEL COVERS VANITY FAIR We may safely

assume, now, that superhero comic books have made it into the upper strata of

the American social order. If not in pulp form at least in celluloid

incarnation. Attesting to this levitation is the cover of the Holiday Issue of Vanity

Fair which offers one of four alternate images, each featuring an array of

Marvel’s superheroes over the headline “s’Marvelous!” Yes, superheroes have made it frequently to the cover of Entertainment Weakly: the new X-Men movie, “Dark Phoenix,” is on the cover of the current “scorching double issue” of “first looks” at next year’s crop of motion pictures. But EW is a gossip magazine. Vanity Fair is classy reportage and thoughtful commentary. The article inside commemorates “10 years of unprecedented moviemaking success. Marvel Studios, which kicked things off with ‘Iron Man’ in 2008, has released 17 films that collectively have grossed more than $13 billion at the global box office; 5 more movies are due out in the next two years.” Money, of course—the ultimate measure, profit—means success in our culture, and Marvel Studios’ $13 billion spells success in capital letters. The article is mostly about “Kevin Feige, the unassuming man in a black baseball cap who took Marvel Studios from an underdog endeavor with a roster of B-list characters to a cinematic empire that is the envy of every other studio in town. Feige’s innovative, comic-book-based approach to block buster moviemaking—having heroes from one film bleed into the next—has changed not only the way movies are made but also pop culture at large. ... Feige knew the idea of cross-pollinating characters and movies had legs.” “The answer,” Feige says, “is always in the book” (i.e., the comic books). And “Disney promises that Marvel has at least another 20 years’ worth of characters and worlds to explore.” The forthcoming “Avengers 4" promises, according to Feige, to be a watershed flick. “‘Avengers 4,’ he said, will ‘bring things you’ve never seen in supehero films: a finale. ... There will be two distinct periods. Everything before ‘Avengers 4' and everything after. I know it will not be in ways people are expecting,” Feige teased. The question here at Rancid Raves is: to what extent will the blockbuster movies re-shape the comic book universes that gave them birth? We’ve already seen the funnybook attempts to cash in on the success of superhero movies by making the four-color characters look like their film incarnations. Captain America now wears a costume patterned after his celluloid appearance. And he’s not alone. But so far, the changes have been largely cosmetic. If “Avengers 4" is going to change everything in the movie Marvel superhero universe, will it also change the print version? Oh—before I forget: Remember Jane Grey, the Phoenix, who killed a whole planet of people and therefore had to die? It was a decree, handed down from high up in the Marvel editorial hierarchy. She was evil. She was too evil to live. Well, as we noted before (Opus 372), she’s back. In the comic book. Phoenix has risen. Just in time for the movie. And it turns out that it was not she, actually—Jane Grey, the Phoenix—who killed all those people. Nope: it was the evil Phoenix Force that had infected her body and made her do bad things. Now she’s cured of that and so we can welcome her back with open arms. So much for moral comeuppance. Sigh. But, hey—it’s only funnybooks, kimo sabe.

CENSORSHIP STILL LURKS The Winter Issue of Defender, the newsletter of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF), reports on the year’s censorship cases and CBLDF’s efforts to quell the assaults on freedom of speech. Some of the books defended in 2017 are: Bone by Jeff Smith Sword Art Online 1: Aincrad by Reki Kawahara and abec Stuck in the Middle, edited by Ariel Schrag The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian by Sherman Alexie Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls Jacob’s New Dress by Sarah and Ian Hoffman I Am Jazz by Jazz Jennings, Jessica Herthel, and Shelagh McNicholas The Kit Runner by Khaled Hosseini Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher This Day in June by Gayle E. Pitman and Kristyna Litten To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee Not all of these books are graphic novels; in fact, few are. And some are “picture books.” Visit cbldf.org for more news about censorship and how CBLDF is fighting it.

MAD FAREWELL By Tom Richmond Mad is moving to California, where it will henceforth be produced by a new staff under Executive Editor Bill Morrison. Richmond attended a farewell gathering in New York and posted this report on December 12—: Last night was a tough night for a lot of the Usual Gang of Idiots. The New York Mad staff is just putting the finishing touches on issue No.550, which goes to press in a week. It will be the last issue of Mad produced in New York City, where Mad has been produced for over 65 years. Last night there was a “wrap” party of sorts for the staff and major contributors at the Society of Illustrators. I flew in from my vacation in Orlando to say goodbye (professionally anyway) to some people who have been a very important part of my life for over 17 years. I turned in my last assignment with the NYC staff on Sunday the 10th. Let me preface what follows by saying this is not a eulogy for Mad magazine. The publication is moving out west to Burbank to join the rest of DC Comics, and issue No.551 is already in production with a new staff under Executive Editor Bill Morrison. I’m already working on my first assignment with Bill and his team, and I’m looking forward to seeing where Mad goes as the 21st century nears it’s third decade. All that said, this is the end of an era. I don’t believe anyone on the new Mad staff ever even met, let alone worked with, original Mad publisher Bill Gaines. A connection to the deep roots of something that was a major part of American pop culture is ending. This is a true changing of the guard. I pride myself in being a professional, capable of detaching myself from the emotional ties that any creative work inevitably is complicated by, but I have to say I have been struggling with this. I cannot really put into words what working with these folks has meant to me. It would be hard to count the ways it’s affected my life and career.

IT’S SAFE TO SAY IT WAS THE FULFILLMENT of a childhood dream. I spend many hours with my 4th and 5th grade buddies pouring over copies of the magazine and drawing our own tv parodies and Don Martin style one page gag cartoons. I distinctly remember when I got my first job in art drawing caricatures at Six Flags Great America in the summer of 1985, walking into the living room of a town house I was sharing with 4 other artists and seeing a stack of Mad magazines someone had brought along. I paged through them remembering how much I enjoyed them as an 11-year-old kid, and then was floored by the artwork that the 11-year-old me did not recognize as genius but the 18-year-old me now saw with an artist’s eye. That was the moment my desire to work for Mad was rekindled. It took 15 more years to realize that dream. It was a career definer. When I joined the National Cartoonists Society in 1998 I was a fledgling freelancer with a few credits under my belt, but nothing anyone would have been much impressed by. The great Mort Drucker sponsored me for membership, and encouraged me to send my work to Mad and keep sending it. I followed his advice, and after many reviews of my work, I was given a shot by the very people I spent the evening with last night. Sam Viviano, Nick Meglin and John Ficarra in particular gave me support and encouragement ,and staffers like Ryan Flanders, Patty Dwyer, Charlie Kadau, Joe Raiola, Dave Croatto and Jacob Lambert (among others) were a true pleasure to work with. To say that was a turning point in my career is an understatement of epic proportions. Mad opened doors for me with other clients that went far beyond the assignments I did for Mad. I would never have won the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben award without Mad, nor likely been president of the NCS. The work I did for the Marlin Company for 15 years, for Jeff Dunham, for Bobby Monihan and Saturday Night Live… so many of the jobs I consider the best I’ve ever done or had came directly from my being an artist for Mad magazine. None of it would have happened had Sam, Nick and John not taken a chance on a guy that they somehow saw might have some potential down the road. I’ve spent the last 17 years trying to earn the trust they showed in me.

IT’S BEEN AN EDUCATION. Another understatement of epic proportions is to say I’ve learned a few things while working with Mad. In particular, Sam Viviano has been a lot more than just an art director over the years. He’s been a coach, a teacher, and a mentor. His support, critiques, and direction has elevated my work in so many ways… not just the individual pieces but showing me how to open my eyes and apply his insights to everything I do. Back when I first started doing the tv and movie parodies for the magazine I really felt my inking was a terrible weak point in my work. I called Sam and offered to pay him to conduct a private workshop in inking with me. He gave up a whole weekend and taught me things about inking and coloring I still use today every time I pick up a pen or brush. I pity the artists who, when art directors ask for changes in the work they submit, curse and bitch about how these idiot A.D.’s are ruining their art. While I sometimes go to bat for certain things I do for a given job, the direction Sam, John and the staff give me almost always makes the work better, and me better as well. And when I do make an argument for something I’ve done that I really feel strongly makes the piece better, they listen and give it real consideration. They might not always let me get away with whatever it is, but they never dismissed me. They made me feel like I was part of a team. They are family. Maybe they never took me to Tahiti, or France, or Africa, or even Yonkers, but Mad still has that sense of family that was legendary in the Bill Gaines era. [Gaines sponsored staff trips to exotic locales as a kind of annual bonus.—RCH] It’s been a true pleasure to know and work with them. While you can say “let’s stay in touch”, the constant communication of those you work with is never replaced with the same frequency and urgency when a working relationship ends. I hope we really can stay in touch. These are amazing people. I’m proud to be able to call them friends. Thanks for the laughs, guys. It’s been a real privilege.

TOP CARTOONISTS RAISE THOUSANDS FOR HURRICANE RELIEF A specialty charity auction of original comic strip art by 34 of the world’s top cartoonists raised $53,384 for victims of deadly hurricanes. Steve Lansdale, PR Specialist, reported that the auction was conducted by Heritage Auctions, collaborating with The National Cartoonists Society Foundation and major strip syndicates. Among the artists whose work was featured in the auction: Patrick McDonnell (Mutts), Lynn Johnston (For Better or For Worse), Mort Walker (Beetle Bailey), Cathy Guisewite (Cathy), Jeff Keane (The Family Circus), Al Jaffee (MAD Magazine), Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman (Zits), Rick Kirkman (Baby Blues), Lincoln Peirce (Big Nate), Greg Evans (Luann), Hector Cantu and Carlos Castellanos (Baldo), Mike Peters

(Mother Goose and Grimm), Dean Young and John Marshall (Blondie) and many other well-known creators. “The results of this auction reflect the spirit of cartoonists and what they do,” said Jim Halperin, co-founder of Heritage. “They create work designed to entertain people, and make them laugh and smile. So it’s no surprise that so many great artists were willing to come together to help raise money for people who have been through so much hardship because of natural disasters.” And here, just at the elbow of your eye, are some of the strips that were auctioned off.

DISNEY BUYS FOX A huge hunk of Fox is about to be under the control of Disney. If the deal that’s pending as this is posted goes through, the Murdoch family will continue to own the Fox tv network and stations, Fox News Channel, Fox Business Network and the U.S. sports channels FS1, FS2, and Big Ten Network. The publishing and newspaper businesses will also remain with Murdoch— New York Post, Wall Street Journal, the Sun and Times in the U.K. and book publisher Harper Collins. Disney gets the Fox movie business, which brings Marvel characters X-Men, Fantastic Four and Deadpool under the Disney roof, where Marvel Studio resides. Disney also acquires Twentieth Century Fox Television with shows “The Simpsons” and “Modern Family,” plus 39% stake in European satellite-tv and broadcaster Sky. At marketwatch.com, Tom Teodorczuk adds: In the statement announcing the sale, Disney said the agreement reuniting the Marvel family under one roof and will “create richer, more complex worlds of inter-related characters and stories that audiences have shown they love.” Disney also gets to complete its “Star Wars” empire with the Fox deal. In 2012 Disney bought Lucasfilm for $4.05 billion but Fox retained the rights to 1977 movie “Star Wars,” cherished by many as the most beloved movie in the entire space opera franchise. They will now revert to Disney which could well be of future commercial, as well as symbolic, value.

ODDS & ADDENDA Recognition at last: Bill Finger, the historically ignored co-creator of Batman, will have a street named after him in the Bronx, where he grew up after he and his family moved there from Denver, Colorado, where he was born February 8, 1914. Finger, like Batman’s other creator, Bob Kane, attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. On December 8, E. 192nd Street at Grand Concourse, just at the southern end of Poe Park, assumed Finger’s name. Abrams has announced that the newest title in Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid series, The Getaway, has sold more than 1.5 million copies worldwide, reported Emma Kantor at publishersweekly.com. “Following the book’s global release on November 7, it held the highest ranking among retailers around the world—including on Amazon in the U.S., Australia, and Germany—and climbed to the number one spot on several bestseller lists in the U.S.” Marvel will launch a new animation series featuring a diverse teen superteam, reported ICv2. The new animation franchise, Marvel Rising, will launch in 2018 with six four-minute digital shorts featuring Spider-Gwen with her new secret moniker, Ghost-Spider, and a full-length animated feature. The team, drawn from recently introduced or modified characters— many of which became popular with audiences new to Marvel— features seven female characters, three male, and one dog (Lockjaw), an unheard of mix. The shorts and OVA will feature a "visually distinct animation style," Marvel Director of Content & Character Development Sana Amanat said in a statement. Warner Bros, under pressure from parent Time Warner, is shaking up the management of its DC film slate, according to Variety. The moves are being taken due to the performance of Justice League, which is not selling tickets at the level needed for a $300 million film that was supposed to be a key cog in the DC Extended Universe. This is nothing new, Warner Bros. also shuffled executives after its last high-profile DC release, Batman v Superman, another critical and box office disappointment. Time, Inc., meanwhile, the “once prestigious” Manhattan-based publisher of Time, People, and Entertainment Weakly, was sold to Iowa-based publisher Meredith Corp, owner of such titles as Family Circle and Better Homes and Gardens. Dunno what that portends, but the deal was underpinned by a donation from the private equity fund of Charles and David Kock (pronounced “kook”), the billionaire brothers known for using their wealth and political connections to advance conservative causes.” “The deal,” saith The Week, “suggests Time believed it couldn’t survive the wrenching shift from print publishing to digital publishing on its own.”

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

FURTHER ADO Here’s Garrison Keillor (tongue in cheek) on the Trumpet—: Why is he so hung up on virility? Because the Army rejected him on account of bone spurs that you get from wearing high heels. Everybody knows that. He quit holding rallies in stadiums because nobody wants to go hear a loser brag about his manliness for an hour; you can hear that in any barroom. Only places he can draw a crowd are rural areas where billboards are riddled with bullet holes, shot by men who are angry because they can’t read. He is so over. Totally irrelevant, exhausted, flamed out. The sleepytime eyes and la-di-da hair and the tweet-tweet-tweet say it all. Real men don’t tweet. Ask anybody. We bark, we protest, we thunder, condemn, denounce—we give ’em hell, sometimes we post Wimps tweet. And now the perps are going to start walking and talking. An that fat lady is waiting in the wings.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy We’re saving up for a Year End review of the last eventful month—Roy Moore, Sexual Harassment Galore on Every Hand, and the Eternal Trumpet, who is “so addicted to bathing in the coverage he provokes that he writes off whatever he doesn’t like as ‘fake news,’” saith Joseph Lelyveld in the New York Review of Books, adding that the Trumpet “keeps himself at the top of the news” every day “with a barrage of demagogic promises and insults.” Until that happy day when you find Opus 374, Part Two, in your box (within a week or so), let’s do this—:

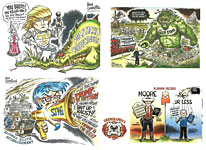

And Now for Something Completely Different—: CONSERVATIVE ROGUE EDITOONIST PROWLS THE WEB The Trumpet is a dream come true for most cartoonists. His toupee-style golden hair, bulky figure, and even larger mouth have made him the target of endless ridicule and derision from editoonists across the country. Except at GrrrGraphics, where Ben Garrison tells a different story in his role as rogue cartoonist. “Spend

any time on some of the internet’s more devoted pro-Trump sites,” says Luke

Barnes at ThinkProgress.com, “and you’ll likely come across one of Garrison’s

cartoons. Instead of using his artwork to mock the President, he frequently

depicts Trump as a young, muscular, all-American hero, standing up to the Deep

State swamp monster or slaying the dragon of Political Correctness. Meanwhile

“‘SJWs’ — internet slang used to refer to liberal activists, or ‘social justice

warriors’ — are blue-haired and shrill.” Some call him Ben “One Man Klan” Garrison. To others, he is “Zyklon Ben.” Elsewhere, he is known as Ben “Not White? Shoot On Sight” Garrison. And those, saith St. Wikipedia, are just his milder nicknames. “But Montana-based artist Ben Garrison isn’t a violent Neo-Nazi, or even a white nationalist. He’s a polite, accomplished cartoonist, with no history of overt or covert racism. His true political leanings are libertarian, anti-elitist, and anti-globalist. “And he is the victim of one the most extraordinary and longest-running smear campaigns on the Internet.” For a mixture of amusement and spite, in a trolling spree that has lasted over six years, Barnes reports, thousands of online pranksters and real neo-Nazis have been remixing his cartoons into racist caricatures. Most Garrison cartoons attack the government, corporations, and political movements. However, almost immediately after Garrison posts a new cartoon, it is remixed into a new version that attacks Jews, African-Americans, or other minorities. These are rapidly disseminated in troll communities and sometimes become more widely-shared than the originals. Like the bandit gang in “The Magnificent Seven,” who perpetually raid the same town for food and supplies, Garrison’s trolls keep coming back for more. Since 2015, Garrison has been the de facto chief cartoonist for right-wing communities online. He now has nearly 100,000 followers on Twitter. Garrison maintains that he is a conservative libertarian cartoonist and that there is no “racist oil” buried within his work. “I don’t draw racist or anti-Semitic cartoons,” he told Barnes. “To be sure, many are interpreted … as such, but I have no control over what people read into them.” He

is also no stranger to controversy. In 2016 he was accused of racism for

drawing a cartoon that featured a pageant-ready Melania Trump next to a butch,

unhappy-looking Michelle Obama.

SINCE 2010 GARRISON’S WORK has been repeatedly altered to create some of the internet’s most vitriolic, anti-Semitic cartoons which, despite his best efforts, still regularly appear on far-right websites and can act as a gateway drug to white nationalism. The trolling began in earnest after Garrison published a cartoon titled “The March of Tyranny” depicting “Global Elite Bankers” walking in jackboots over both Democrats and Republicans (just posted in the previous visual aid). While it’s often suggested that “globalist” language is a dog-whistle to anti-Semitism, Garrison’s work was then altered to be explicitly so, featuring the “Happy Merchant,” which is arguably one of the most widely seen anti-Semitic images in history. Garrison tried his best to get the hijacked cartoons taken down, claiming that they were libelous. In 2011 he posted on his personal blog that “there’s an entity or unknown cretin out there changing my cartoons – adding in offensive Jewish stereotypes – and then spreading them throughout the internet.” The trolling continued unabated. In 2014, Garrison once again wrote that “Trolls had stolen my artwork and…concocted an entire page devoted to spewing libelous hate.” At one point he wanted to sue Andrew Anglin, the founder of the Neo-Nazi Daily Stormer website, but lacked the financial means to follow through. According to Garrison, “the dopplegänger created by the trolls is finally dead, but it took plenty of hard work to reclaim [his] own voice.” Despite this, remnants of the trolls’ libelous hatred remain. Type in “Ben Garrison quotes” into Google images and you’ll see dozens of photoshopped pictures of Garrison with quotes advocating a second Holocaust and a race war. Type in “Zyklon Ben” — a nickname the internet concocted for him — and you’ll be linked to images of racist and virulently anti-Semitic cartoons. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), these cartoons have helped white nationalists spread their message online by coating the themes of racism, anti-Semitism and misogyny in layers of humor and irony. “These cartoons make the rounds on every white nationalist site I know,” said Keegan Hankes, Intelligence Analyst for the SPLC. “They’ve become the trading cards of the alt-right; these memes play a huge role in getting people active online. There are tons of [alt-right] Facebook groups which have started by sharing them.” Hankes’ remarks can be seen as an objective assessment of the Garrison cartoons’ role in spreading the white supremacist doctrine. But to Garrison, such comments seem aimed at him rather than the trolls. When asked about the SPLC’s comments, Garrison described them as “utter bunk and sactimonious pap” which he would gladly ignore. “I’m a conservative and anyone conservative is automatically labelled as ‘far right’ by them,” he said. “It’s similar to Hillary arbitrarily deciding the Pepé the Frog is a symbol of Nazi hate speech. Pepé is a symbol of freedom of expression and various emotional and political states by a vast number of young people from all political persuasions.” (For more about Pepe, see Opuses 366 and 371.)

FOR HIS PART, in 2014, Garrison called on Facebook to block hate speech, like the hijacked cartoons his trolls post, before it became more established on mainstream social networks. “Hate speech is not free speech,” he wrote at the time. “Hate speech is blind, one-dimensional blackness. It is not reasoned debate. It loudly shouts for the murder of human beings and Facebook is providing them a megaphone for that purpose.” Barnes says Garrison has described Trump as the “last, best chance to restore justice and the Constitutional Republic as it should be.” In particular, he added that he was glad Trump was trying to secure the United States’ borders “from endless immigration – particularly a flood of Muslim immigration that is currently destroying Europe.” He added that he viewed Trump’s most perilous task as dismantling the Deep State. Still, says Barnes, Garrison isn’t in favor of everything Trump has done so far. He added that Garrison was disappointed in several policy decisions made by Trump, including the “continuance of the perpetual quagmire in Afghanistan” and his decision to “populate his administration with Goldman Sachs men.” Like many Libertarians, he maintains a deep-seated hatred for the Federal Reserve. “Most Americans live paycheck to paycheck and own no stocks while the ultra rich rig the system to get stupendously wealthy because they have access to the Fed printing press,” he said. “We have a fundamentally immoral system of money and Trump is apparently not going to try and fix it.” Says Barnes: “Garrison is entirely unapologetic — for his political views, his stances, and his cartooning style. He’s not at all bothered that many on the left view them with contempt. What’s more, his popularity on the right wing, especially among a pastiche of alternative media figureheads, means he’s unlikely to be stopping anytime soon.” “During my newspaper days,” Garrison told Barnes, “I observed several neo-liberal cartoonists spending years fretting about winning a Pulitzer. They all had big egos and wanted to be ‘the best’” he said. “I’ll never be the best and I don’t think in those terms. If my cartoons sway .001 per cent of the population, then it would be worthwhile for me.” Here’s some more from GrrrGraphics.

Compared to most editoons of the day, many of Garrison’s are overwrought: the central image in some is almost crowded out by dozens of visual and verbal snipes. The Al Franken cartoon is the simplest I’ve seen from Garrison: unencumbered by any other message or subtext, it makes its point clearly: Franken is guilty of a crime and so he should be in handcuffs. The Hillary Clinton cartoon, on the other hand, is burdened with several messages. While Hillary Revere is warning, Paul-Revere style, of the Russians “coming”—a persuasive image depicting hysterical panic—the background is full of other minor messages. People yelling at her that she’s lost the election so she should give it up. Or she should be locked up (echoing the Trumpet’s pep rally cry). “Buy my book,” she says, making book sales a part of her crusade, thus, materialism trumps patriotism. But “Hillary Revere” is simple compared to the “Deep State” swamp-draining cartoon on our first visual aid. Floating in the swamp are a half-dozen other Trump targets—money men like the Rothschilds and Soros (the vulture in the tree), Hillary and Comey swimming together as dragons or serpents, the mainstream media (as a boatload of rats), and way in the distance, near the capital building, a Bilderberg globalist. Any one of this multitude of sinners could be a target, but here, they present a diffuse image. All of which no doubt delights Garrison’s readers, who see all these encumbrances as part of the problem. But the monster coming out of a swamp all alone would have focused the attack. But Garrison, like his fans, sees the complexities as well as the over-all giant problem. Similarly, in the cartoon showing Trump having slain the Political Correctness dragon, Garrison puts in a wholly extraneous picture of Jeb Bush, calling Garrison’s triumphant hero names that are blithely ignorant of the hero’s achievement. The picture of Trump in armor standing victoriously over the PC dragon is not diminished by the addition of Bush, but without Bush, it would have been stronger. Still, it’s fun to discern all the minor chords in Garrison’s symphony of assault.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution

HAVE YOU HEARD? It's simply not true that Myanmar's military leaders are massacring the Rohingya Muslim minority. Never mind the eyewitness accounts of soldiers throwing babies into fires, or the photos of the more than 600,000 starving Rohingya who've fled to squalid refugee camps in Bangladesh. "There is no such thing as Rohingya," a Myanmar official declared this week. "It is fake news." Ah, fake news. Such a useful concept. Totalitarian states have long known its power and utility, but autocrats are now taking lessons from the U.S. Crying "fake news" can magically erase any inconvenient evidence, whether it points to genocide, the destructive impact of rising global temperatures, Russia's election interference, or a favored politician's predations on teenage girls. The lying media made it all up! Our nation is having what philosophers might call "an epistemological crisis." That's a highfalutin way of saying many people no longer know what it's possible to know. If nothing the media reports can be trusted, if scientists are frauds, if there is no reliable source of information or verification — then how do you distinguish between "fake news" and reality? You cannot. This can be disorienting at first, but it can also be marvelously liberating: There is no objective truth — just what you want to believe, and the "biased" beliefs of the enemy. Thus, in Alabama, 71 percent of Republicans say they don't believe that senatorial candidate Roy Moore preyed on girls in their teens, despite the detailed accounts from eight women. The president's attorneys are now saying he can't be accused of obstruction of justice, even if he tried to shut down the Russia investigation, because "the president is the chief law enforcement officer." In 1984, George Orwell described a dystopian world in which citizens are taught: "War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength." Surrender to the paradox, and you are free from all doubt. —Willliam Falk, Editor-in-Chief, The Week, December 15, 2017

The Arrival of the Orwellian State The ever-vigilant Washington Post reported on Friday, December 15, that the Trump administration has banned certain words and phrases in official budget documents from the Center for Disease Control. The significance of this seemingly harmless vocabulary adjustment is quickly apparent: if you can’t use, say, the word “fetus” (one of the banned) in a budget document, then you can’t request money for any project involving fetuses. CDC officials who were questioned about the ban said they weren’t sure, hadn’t seen the list, or didn’t know at all—and claimed anonymity, which suggests the ban is in effect but no one wants to admit it because they fear reprisal from the Trumpsters. Then on Sunday, December 17, Caroline O. at arcdigital.media reported that the list of banned words is even more extensive than initially reported, encompassing additional terminology and extending beyond the Centers for Disease Control. The remainder of this report is mostly hers. The list of seven words banned at CDC includes “science-based,” “evidence-based,” “vulnerable,” “entitlement,” “diversity,” “transgender,” and “fetus.” [Reminds me of George Carlin’s notorious seven words you can’t say on television. But the Trumpsters are serious, dead serious. They want to change the world.—RCH] At an HHS agency, officials were told not to use the phrases “entitlement,” “diversity,” and “vulnerable” in documents. The agency was also told to use “Obamacare” instead of the “Affordable Care Act.” Similar directives were issued at the State Department, where employees were told to refer to sex education as “sexual risk avoidance,” a term that generally refers to abstinence-only education. [No condoms.] This is in line with the contents of a White House memo that was leaked in October, revealing the administration’s plans to wage war on women’s health and reproductive freedom. The list of prohibited words provides a revealing look at the ideological underpinnings of the Trump administration’s escalating war on science and collective knowledge, which builds on long-running conservative attacks on society’s central information-gathering and -disseminating institutions. It also serves as a chilling reminder that although Trump’s assault on truth may be most glaring when he lies on camera, it is most dangerous when it plays out behind the scenes. During a briefing on Thursday before the list was made public by the Washington Post, CDC officials were given alternative phrases to use for some of the forbidden terms. Instead of “science-based” or “evidence-based,” they were directed to say “[the] CDC bases its recommendations on science in consideration with community standards and wishes.” It’s not clear what community this statement is referring to, but including the “wishes” of any community in the assessment of scientific evidence undermines the objectivity of science-based conclusions. [The “wishes” of an increasing number of parents refusing to vaccinate their children has resulted in diseases like measles—once almost eliminated in the U.S.—making a come-back. Must we take these parents’ alternative facts into account when assessing the effectiveness of vaccines?—RCH]

THE AGENCY WAS NOT TOLD how they should refer to the now-banned words—some of which, like “fetus,” are standard medical terms that can’t simply be replaced with another word. That’s not an accident. In fact, that seems to be the entire point of this new Orwellian directive. By prohibiting the use of the word “fetus,” the Trump administration is trying to force government health agencies to adopt clumsy and/or medically inaccurate terminology favored by anti-abortion advocates— phrases like “unborn child” and “baby,” which have moral but not medical or scientific meaning. Based on the Trump administration’s list of forbidden words, the future of such initiatives may now be in jeopardy. After all, it’s hard to run an effective program if you can’t describe it in a proposal for funding. This latest move is part of a broader pattern, carried out by officials in the Trump administration, of reducing and undermining the role of science in public policy, giving industry and corporate interests an oversized role in decision-making, creating hostile workplaces for government scientists, and reducing, manipulating, and sometimes even cutting off public access to scientific information. Just days after Trump took office, scientists and other staffers at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service were told to stop releasing “any public-facing documents,” including “news releases, photos, fact sheets, news feeds, and social media content … until further notice,” according to an internal email obtained by BuzzFeed. The ban was later rescinded following public outcry. Six months later, employees at the USDA and several other government agencies were ordered to stop using the term “climate change.” Instead, they were directed to reference “weather extremes.” The phrase “reduce greenhouse gases” was also blacklisted and replaced with “build soil organic matter, increase nutrient efficiency,” while “climate change adaption” was changed to “resilience to weather extremes.” And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The consequences of scientific censorship extend far beyond the phrases, topics, and agencies specified in the Washington Post report. Science is the best tool we have for understanding and describing the world around us. If scientific terminology is restricted and shared vocabulary discarded, science will suffer. People will too. Perhaps most perilously, censorship of this kind not only undermines the scientific process —it threatens to erode the very concept of objective truth.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

FARTING, as a

basis for comedy in the “modern” daily newspaper’s comics section, has clearly

gone mainstream. As proof, we offer the line-up in this display. The word shows up in all its unabashed innocence in the rest of this exhibit—Mark Tatulli’s Heart of the City, Hilary Price’s Rhymes with Orange, and Jef Mallett’s Frazz, about a janitor in an elementary school and the pupils he gets to know (and vice versa). I’m not sure Rhymes with Orange needs the footnote in the opening panel. It’s the squirrel shape that makes the joke here, not the expelled acorn-smelling farts. And Frazz and one of the school’s more eloquent pupils, Caulfield, actually discuss farts at some length—two daily installments. High class philosophy.

THE COMIC STRIP BLONDIE is our concern here. At the Now, this circumstance is unusual for Blondie. As a historical fact, Blondie is one of the last remaining comic strips in which the figures are routinely (almost always) displayed at full height, head to toe—as we see in the next strip down the page in which Dagwood and his boss Mr. Dithers are depicted. Ditto the strip below that. Full-length is the visual norm in Blondie, which is why the Sunday strip at the top gave me pause. Is this an indication of future Blondie? I wondered. But only for a day. By the ensuing Monday, things were back to normal. Everyone at full height. And every time the setting is the Bumstead domicile, the dog Daisy is there, too—also at full height. A lot of extra drawing, you might say, but it enhances the illusion of reality that should infest every comic strip. Finishing off with a stop at Baby Blues by Rick Kirkman and Jerry Scott, we pause simply to admire the wit and humanity. Nicely done.

NO, IT’S NOT

WRONG to go to comic strips in search of wisdom. We just saw an example of that

with the preceding Baby Blues. Pluggers’ wisdom might very well be a life’s watchword. Works for me. And the physically restorative prowess of chardonnay I’d overlooked somehow (perhaps because I have a preference for reisling instead). But Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman in Zits show me the error of my ways. Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur is perfect. And so profoundly human. And then we have the panhandler in the back, helping himself to whatever’s in that lady’s purse. And in Jef Mallett’s Frazz this time, we have Caulfield up to his usual tricks—asking unanswerable questions. Drives his teachers nuts. As he should.

COMIC STRIPS

OFFER ANOTHER KIND OF TREAT when they are being self-conscious, when the

characters in them (or, sometimes, just the cartoonist) know they’re in a comic

strip. Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur isn’t particularly self-conscious in our example, but it is doing something we don’t see often. Notice the book one angel is reading. Mad. And just behind him, another angel is partaking of Mrs. See’s candies. Delicious. At the right, we’re back to self-aware comics in Bill Whitehead’s Free Range. And again in McDonnell’s Mutts at the bottom. Nothing profound here. Just fun stuff.

FOR PROFUNDITY, we go to Sally Forth by Francesco Marciuliano as drawn by Jim Keefe. For several days—a couple weeks or more last month—the strip focused on Sally’s husband Ted, whose father was dying. In a hospital. In a bed. There’s nothing funny about any of the strips in this sequence. Except, maybe, that they show a human experience common to all of us—the death of a parent—and in that commonality perhaps we find ourselves smiling sympathetically. But not laughing. Marciuliano doesn’t make a habit of this kind of continuity. Tom Batiuk in Funky Winkerbean does. Recently,

Les, whose wife Lisa died of cancer several years ago—a sequence that Batiuk

reprised in book form (and then returned for two more books on the subject,

“Lisa’s Legacy Trilogy”)—is seen for several days engaged in some sort of

bookish “celebration,” an author’s reception of some kind. The Lisa book is

seen in the strip as Les’ book; he wrote it. For a while in this Batiuk has earned applause from readers and other civic-minded souls for taking up serious matters in his strip. “When Lisa’s cancer story started in the newspapers,” Batiuk said recently, “University Hospitals created the Lisa’s Legacy Fund for cancer research and education.” What’s more, the Funky Winkerbean 5K run and walk in Mentor, Ohio, benefitting the Fund, continues. Consulting with various kinds of experts, Batiuk presents ways of coping with the vicissitudes of life. The Lisa sequence was organic: it grew out of circumstances in the strip’s story. But often it seems to me Batiuk goes searching for “causes” to espouse. I’m sure comic strip treatments of such delicate subjects help people. And I scarcely begrudge him the effort. But it makes keeping current with the strip sometimes difficult because the cause often involves a minor character or a new one, invented expressly to embody the cause. And Batiuk hasn’t made it easy for us. Twice he’s jumped his strip forward by years, and as a result, most of the characters don’t look like they did in the previous incarnation. We have to identify them all over again. In another recent sequence, the action involved actors and Hollywood types engaged in producing or premiering a movie based upon a fictional comic book character of Batiuk’s devising. Who are these actors and script-writers? Dunno. I read the strip regularly, but I’m often completely lost. Sally Forth looked like it had wandered off its reservation onto Funky’s turf. It went on for a long time. Ted is seen in the immediate aftermath of his father’s death comforting his mother (and being comforted by her) in a stark, wordless panel. Then there’s the funeral. Once more, Ted betrays his grief in terms of wanting to talk with his father just one more time. And then, finally, we reach the end of the sequence, a Sunday in which Ted plays an old recording. And in tiny print at the top of the last panel, we find the rationale for this sequence: Marciuliano has written it all in loving memory of his own father. I knew there had to be something personal involved. I’m not sure this is a good thing for comic strips to get into. But many nowadays do just that, get into topics beyond the customary scope of the funnies. And many readers appreciate the sympathy they find there. It probably started with Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse.

TO PROLONG the

meander off into the realms of realism that Tom Batiuk has been

exploring, here are extracts from a recent sequence in which a bunch of old

guys form a band. I know, though, that Harry L. Dinkle was the highschool band director, so the name, at least, is familiar. But which of these old dudes is Dinkle? Or is he there at all? Finally, thanks to the fourth strip down the line-up, I realize that Dinkle is the guy referencing Harry L. Dinkle in the first strip. When Batiuk started taking up causes to promote, he gave up “gag-a-day” stripping. He no longer feels a compulsion to end each installment with a joke. And that just leaves me even more lost than ever. The second silent strip is not only missing a punchline: it seems not to be connected to either the strip the day before (above it) or the one the day after (below). The one below seems to want to end on a humorous note; but what’s the significance of the knife gag? I can’t make sense of that even as an isolated utterance. At least the strip at the bottom, out of the preceding sequence, ends on a chuckle. And since I’ve seen the ducks in action at the Memphis Peabody, I like the reference. But the rest of the old guys band series—leaves me cold, kimo sabe, just frozen out.

FOR SOME YEARS

LATELY, various comic strip characters have wandered out of their home strip

into a neighboring one. In Mother Goose and Grimm, Mike Peters has Grimm visiting Family Circus. It’s the logical (well, in comic strip kingdom) place for him to go if he’s running away to join the “circus.” And then in Brad Anderson’s Marmaduke, Marm’s home is visited by an orange cat from another strip, namely, Garfield. I think such maneuvers are risky: to get the jokes, the readers must know both strips. And maybe sometimes they don’t because their paper doesn’t carry both strips. Another sort of guest shows up in Hector Cantu and Carlos Catelllanos’ Baldo. Yeh, that’s the Trumpet blurting forth from the tv set in the first panel. I’m not sure if the woman in the next panel is Melania or Ivanka. But it makes the gag either way. Finally— AT LAST WE KNOW: Beetle is sleeping with Miss Buxley! We know they’ve been dating for a long time. But here we’re taken a little further. This strip doesn’t say as much in so many words, but the hints are there. First, the reference to Beetle’s “bunk”—his bed. Unoccupied. Why? Because, he explains, he was at Miss Buxley’s. So if he wasn’t in his bunkhouse bed, was he in hers? It’s this sort of tortured syntax that’ll get you in trouble.

WE BEGIN THE

NEXT VISUAL AID with a contemporary reference. I’m all in favor of doing whatever we can to eliminate the harassing of women in the workplace. It must be harrowing for a woman to enter any room with men in it not knowing whether one of them will make a crack or a grab that demeans and diminishes the woman as an individual person. As a skinny unathletic kid in high school, I experienced what I imagine is a kindred sort of trepidation about how I might be treated every time I wandered out of the house into the company of other kids my age, all of whom were weight-lifters and athletic. But it seems to me that firing Garrison Keillor because he accidentally patted a woman on her bare back is a little extreme. He said at the time, and later, that it was a simple mistake: her shirt was open at the back, and when he went to pat her sympathetically after hearing her sad story, his hand inadvertently got under the shirt and next to her skin. For which, he said, he immediately apologized—and again in a missive to the woman. We’ll get into this a little more in Opus 374, Part Two. But for now, I wonder what benefits the frenzy will bring us. More Keillors? More Al Frankens? Maybe not enough Matt Lauers and Harvey Weinsteins. Apart from that, I worry about the inevitable backlash. And Wiley Miller in the Non Sequitur strip at the top of our line-up gives verbal-visual voice to one of my concerns. Will men who are in a hiring position want to hire women anymore? Extreme, I know. But not beyond the pale of possibility. Next down the line is a very boring-looking Blondie. All the visuals, panel to panel, are the same. And drawing that automobile three times must have been as boring a task as looking at the results. Or did John Marshall just photocopy the first panel twice and change Dagwood’s head position—and Herb’s eyebrows in the last panel? I’d opt for photocopying just to save my sanity. The joke in Hilary B. Price’s Rhymes with Orange nearly escaped me. Then I remembered that Rockefeller Center in New York City always installs a giant Christmas tree for the season. But in Mother Goose and Grimm, Mike Peters has completely lost me. The joke involves a play on words, obviously. The poodle might be the pet of the teacher in the same way that Grimm is a pet of Mother Goose’s; or the poodle might be the teacher’s favorite in the class. This confusion seems at the heart of the gag, but I can’t be sure. And even if I were sure, I don’t know that I’d be amused. Finally, in our continuing effort to understand the relationships in Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff (as rendered for most of its run by Al Smith), we offer this specimen in which Mutt is clearly in bed with his wife. Irrefutable. But we’ve also posted here from time-to-time strips in which Mutt is in bed with Jeff. So which is which? Merry Christmas.

TICS & TROPES Winston Churchill, the great British statesman, wrote a book in the 1930s about his youth and his adventures in South Africa during the Boer War (1899-1902). By the end of The Story of My Early Life, he’s in Parliament, and he concludes his narrative with this: “Events were soon to arise in the fiscal sphere which were to plunge me into new struggles and absorb my thoughts and energies at least until September 1908, when I married and lived happily ever afterwards.” Never thought of Churchillian prose as even remotely mischievous, did you?

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—:

Babes In Arms: Women in the Comics During the Second World War By Trina Robbins 176 7.5x10-inch pages, color; 2017 Hermes Press hardcover, $60 THE BABES OF THE TITLE include both funnybook heroines and the women who drew them, the latter are Barbara Hall, who drew Girl Commandos; Jill Elgin, ditto; Lily Renee, Jane Martin and Senorita Rio; and Fran Harper, Jane Martin. Robbins supplies a short overview of the subject (noting that the number of women doing comic books increased during WWII because all the men were being drafted into military service) and brief biographies and photographs of the four women artists. The reproduction of the comic book stories is uneven, going from muddied to sparkling, probably because the source material didn’t always present a clear uncluttered image. The artwork is likewise uneven. Hall’s work is the least accomplished, Harper’s a step up, then Renee with Elgin the most expert of the four. There’s very little text in the book, and what there is, is much too small to read in many instances. I thought agate type went out with letterpress.

The pictures are not as sexy as you might suppose, given the “good girl art” trends of the 1940s. The women are more leggy than bosomy. But fetish lurks. In the Girl Commandos stories, one of the Commandos gets strung up by her thumbs just about every time. Put this one on your shelf: it’s a solid if rare insight into the WWII action/adventure comic book.

Terry and the Pirates by George Wunder: Volume Two, 1948-1949 Introduction by Eileen Sabrina Herman 256 10x13-inch pages, b/w daily strips, color Sundays; 2015 Hermes Press hardcover, $60 WHEN WUNDER TOOK OVER Milton Caniff’s seminal comic strip in 1946, he drew in Caniff’s manner, and he continues in that fashion through his second year on the strip, rehearsed in this volume, which takes the strip from February 1948 to March 1949. Terry and Hotshot Charlie are still running their own cargo airline, Air Cathay, with the help of the front office manager and resident con-man, the immensely chubby Chopstick Joe. Otherwise, most of the characters in this tome are newcomers. In the first story, Harrington Von Goblin and his beautiful daughter Motley hire Air Cathay to take them into the Chinese interior where they hope to plunder a ruined village for artworks of high value. In the second story, Hotshot’s love life, Spray O’Hara, returns, and the gang goes looking for a kidnapped Chinese kid, Chum Fun, who is smarter than all the rest. In the last tale, Terry and company encounter a snooty baroness, Alexi, and a short but ultimately meaningless love story transpires. Wunder’s storytelling is at least as convoluted as Caniff’s—and as laden with snappy patter. Reproduction

is not entirely excellent but better than merely fair. The Sundays in color are

glorious, but in the dailies, although running at gigantic size (3.5x11.5

inches, only two strips to a page), fine lines often drop out, resulting in a

somewhat muddy appearance. The volume Hermes, I’m told, will not continue this reprint project: sales weren’t good enough. But in the two volumes it did produce, we have ample evidence of Wunder’s skillful continuance of Caniff’s iconic strip. Wunder would eventually develop a stylistic variation that became increasingly peculiar in the rendering of facial details. But there’s only a suggestion of that oddity in these pages.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons By David A. Bossert 176 9x12-inch pages, b/w and color; 2017 Disney Edition hardcover, $40 HERE IS THE

WHOLE STORY of Walt Disney’s first animation success, how it (Oswald) was

stolen from him through an underhanded maneuver

The Bible By Sheldon Mayer (story) and Joe Kubert (pencils) and Nestor Redondo (inks) 72 10x13-inch pages, color; 2012 DC Comics hardcover, $20 THIS SLENDER VOLUME is but the first in a series DC Comics contemplated but never finished. Published initially in 1975 as a giant-size comic book, it is reissued in this permanent hardcover form. Judging from an afterword essay entitled “A Dream Comes True,” the publisher was hesitant about producing the Bible in comic book form, thinking, doubtless, that many people would regard the effort as sacrilegious, that the holy book would be contaminated by the comics. To address this imagined objection, Mayer is said to have “researched many variations of Biblical publications, delved into histories, commentaries and translations in an effort to elicit the best information possible for our project.” In other words, the book isn’t just a comic book. Nor is it the complete Bible. It includes adaptations of the Creation, the Garden of Eden, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Flood, the Tower of Babel, the Story of Abraham, Sodom and Gomorrah. And scattered throughout are special features on school days in Biblical times, soldiers in the time of Abraham, the ziggurat, and archeological findings. The artwork is impressively grand. The giant page size is impressive in and of itself: it imparts stature to the pictures. Kubert’s pencils match the dimensions in grandeur of design, and Redondo’s inks are exquisitely detailed (although he overwhelms Kubert’s style, none of which remains).

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE Questions from the unconquerable Maxine—: Why isn’t the number 11 pronounced onety-one? If 4 out of 5 suffer from diarrhera, does that mean that one out of five enjoys it? Why do croutons come in airtight packages? Aren’t they just stale bread to begin with? If lawyers are disbarred and clergymen defrocked, then doesn’t it follow that electricians can be delighted, musicians denoted, cowboys deranged, models deposed, tree surgeons debarked, and dry cleaners depressed? What hair color to they put on the driver’s licenses of bald men? [Mine says “white,” but then I do have a few strands of hair and it is—or they are—white.]

BOOK REVIEWS Lengthy Critiques & Crotchets

Oh My God—They Printed That?! By Carson Demmans 295 6x9-inch pages, b/w; 2017 BearManor Media paperback, $25 MAYBE WE NEED A BOOK ON THIS SUBJECT, and maybe we don’t, but if we do, this is not it. The subject is the verboten—that is, all the comics material that today’s Political Correctness (not to mention simple human decency) forbids comics to depict: “niggers and coloreds” (as Demmans puts it in this volume’s table of contents), sexist women, “injuns and redskins,” “nips and chinks,” and “spics and wetbacks.” As you can readily see, Demmans doesn’t mince words. The first chapter includes a liver-lipped African American kid named Steamboat who appeared in Fawcett’s Captain Marvel as well as the earliest manifestation of Marvel’s Luke Cage: Hero for Hire (he speaks a stereotypical Black dialect). The “injun” chapter mentions Little Hiawatha but gives most space to Big Chief Wahoo. The Asian stereotype chapter features Kato, the Green Hornet’s sidekick, and the early horror creature, the Claw, and Chop Chop from the Blackhawks, plus Charlie Chan and Dr. Fu Manchu. Among the Hispanic characters mentioned in that chapter are Senor Banana, Senor Siesta, and Senorita Rio. In a chapter entitled “Too Outrageous To Classify,” we have Al Capp’s Li’l Abner and Boody Rogers’ Babe. But the longest chapter in the book—64 of the 295 pages, or 20% of the book—is devoted to sexist comics. Or, perhaps, “sexy” comics, those that feature bodacious babes like Bill Ward’s Torchy and Matt Baker’s Phantom Lady, plus a raft of comical distaffs, Suzy, Moronica, Dizzy Dames, and the “Farmer’s Daughter.” Although Demmans’ survey of yesteryear’s comics that he regards as disgraceful is scarcely complete, the reason this book isn’t the book on the subject that we might need is that the illustrations are much much too small. There are lots of them, but all are tiny. Comic book full pages are reproduced at a 4x6-inch dimension. Too small to read the words or to discern the content of the pictures, and since the pictures are the chief reason for condemning these funnybooks, their illegibility in this book is a severe indictment of it. And they’re all in black and white and gray, too, not in color, which would have made them more legible. I’ve included a sampling of these illustrations, and they are readable here because the scan focuses on each page and, in effect, enlarges it.

But the other reason that this book is inferior is Demmans’ prose. He is an attorney, he tells us on the back cover blurb, but he is also a humor writer. And it is the latter that scuttles the text: he can’t resist making a joke or a witticism at any and every opportunity. And there are hundreds of opportunities. Demmans captions every comic book page he reproduces, and the captions are bursting with wit. For one page of the Captain Marvel story with the black kid Steamboat in it, he writes: “Steamboat’s grammar was so bad it should have come with an English translation.” Sparkling. About Minni-hacha in Big Chief Wahoo, Demmans observes: “I’m sure that all Indian women wore fur stoles with their traditional garb in the 1930s.” About a page of Charlie Chan: “Little known fact: realizing there was no money in philosophy, Confucius also wrote pulp fiction.” About an Asian villain: “You would think that mega-rich criminal geniuses like Chin Lung and Fang Gow could afford a decent orthodontist.” (To have their fang-like teeth fixed.) About

the scanty-halter-wearing pneumatic Phantom Lady, Demmans writes: “Other than

her own title for Fox, she appeared in the appropriately named All Top

Comics, which was fitting for a character that was all top.” About the voluptuous women in the chapter devoted to them, Demmans marvels: “Gravity-defying boobs with glass cutter nipples were the norm for women in this genre. I wonder if the inventors of silicone implants were avid comic book fans?” He resorts to “glass cutter nipples” a couple of times in describing the drawings of bosomy bimbos. He seems oblivious to the meaning of the metaphor. Diamonds cut glass, so a nipple that can cut glass is as hard and sharp as a diamond. But in none of the pictures to which Demmans applies this description are nipples visible. In a similarly baseless manner, he assumes that the Farmer’s Daughter and other humorous female characters don’t wear bras. Or any underwear at all. And for the latter reason, he is obsessed with pictures of the women that suggest someone is looking up their dresses. Another of Demmans’ preoccupations is to remind us, endlessly, that his book is not intended to endorse the stereotypical evils it presents. “This book will, hopefully, scare you. We say hopefully because hopefully they will frighten you at the thought that these images were once in fact perfectly acceptable.” But, he hastens to add, they no longer are. Definitely. Absolutely.

DEMMANS’ FINAL SIN is that he is often not very accurate. And sometimes, he is downright misleading. His desire to make a joke leads him astray: to concoct the witticism, he shortchanges the facts. He strives always for a breezy light tone, an intention that tempts him to glide effortlessly—factlessly—by dates and other facts. He alleges that Big Chief Wahoo “was supposed to be called The Great Gusto and was supposed to be about a patent medicine salesman based on W.C. Fields.” Gusto’s sidekick was a stereotypical medicine show Indian, Wahoo. No: not “supposed” to be—actually was. The strip began as The Great Gusto, no supposition about it. Wahoo proved more popular with readers, though, and soon elbowed Gusto out of the strip. In his “Too Outrageous” chapter, he includes a long segment about Li’l Abner, consisting mostly of a list of 12 “plotlines and characters” that demonstrate that the strip, although featuring hillbillies, wasn’t actually about hillbillies. After the list, Demmans concludes: “But other than the sex, the ethnic stereotypes, more sex, misogyny, sexism, and sex, it was basically about hillbillies.” Funny quip, eh? He fails utterly to see the satire for which Li’l Abner was most celebrated. But he gets his joke in. It’s not about hillbillies: it’s about sex. In the interest of establishing the latter, he publishes pictures of three of Capp’s babes—Daisy Mae, Stupifyin’ Jones, and Moonbeam McSwine; but the picture of Moonbeam was not drawn by Capp (or by any of his assistants). Despite the book’s considerable flaws, I found things I value in it. The pages of Moronica and the Farmer’s Daughter, f’instance, are lively and comical, enjoyable to behold. Demmans doesn’t know who drew Moronica, but I suspect it was Owen Fitzgerald (and Lambiek.net confirms my suspicion), who also drew lots of the Bob Hope comic book. Demmans also includes in the last “Outrageous” chapter the entire “Mystery Mountain” story starring Boody Rogers’ Babe. Says Demmans: “It is so horrible and bizarre that nobody believes it actually exists.”

After a few pages showing Babe with a bit in her teeth, I agree with Demmans about the story’s horribleness. In summary, don’t get this book for the accuracy of its history; get it for its chatty glimpses of comics now obscure enough to be entirely forgotten—visual glimpses and, yes, even some text glimpses.

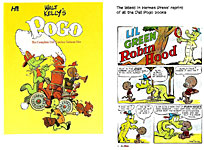

Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, Volume 5 By Walt Kelly; Introduction by Thomas Andrae 176 8x10-inch pages, color throughout; 2017 Hermes Press hardcover, $50 WITH THIS VOLUME, Hermes Press is within eye-shot of completing its project of reprinting all of the Dell Comics Pogo. Pogo Possum Nos. 12 - 14 (April/June 1953 through October/December 1953) are presented in this volume. Reproduction is superb (color is stunning without being at all garish) and complete: even Dell house ads are reprinted herein. You won’t find any of the political satire for which Kelly is justly famed. That was confined to the newspaper Pogo. In the comic books, Pogo and Albert and the rest of the swampland critters engage in a species of playacting; they start with whimsical parodies of various shreds and patches of Western literature and rapidly descend (or ascend) into merciless nonsense. Herein, for instance, we have “Little Green Robin Hood” in which Albert dons the feathered cap of the famed Sherwood Forest outlaw. Albert, however, thinks Robin Hood’s main job is shooting an apple off William Tell’s son’s head with a bow and arrow, and he drafts Pogo to stand under the apple. In lieu of an apple, they use an apple pie. Albert then wanders off in search of a bow (and an arrow) and the story deteriorates hilariously from then on. Well, you had to be there. Elsewhere

in the book, we also encounter “High Noon, the Fiasco Kid Writhes Again” and a

tale about Rip Van Winkle and the reprint of a Christmas story from Animal

Comics, the comic book in which Pogo debuted. The volume concludes by

reprinting Animal Comics covers from Nos.1-3, 5, 8, 9, 10-28, a couple

of which do not seem to be by Kelly. Andrae’s introductory essay is completely off the subject. He writes about Kelly’s satire of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer stories (I, the Jury et al), none of which appear in this book. And as he sometimes does, Andrae often misses the point. In summarizing the adventures of Spillane’s hard-boiled detective, Andrae fails to give the character’s full name, calling him only Hammer, and in reviewing Kelly’s testimony before the Senate subcommittee investigating comic books, he takes Kelly’s tongue-in-cheek satirical comments as serious analysis. But you don’t buy this book for Andrae: you buy it for Walt Kelly’s Pogo, and that’s what you get here, in sumptuous color and rollicking parody. The sixth and last volume in the Hermes project is presently being printed. It will include Pogo Parade, a Pogo story from Our Gang No.67, a Pogo Christmas story from Four Color No.254, an unpublished Pogo story, an unpublished Pogo Possum cover, original art from the series, and a gallery containing all of the Pogo Possum covers. I can’t wait.