|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 361 (December 16, 2016). The date you just

read is the posting date, about 2-3 days after I finished writing this colyum

of trifling languor, indifferent whimsy and lasting trivolity. This

introductory effusion, however—the paragraph now under your very

eyeballs—includes our own anyule greeting.

And now, here’s

what’s here, in order, by department—:

JUST ANOTHER LAST WORD ON THE ELECTION Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen and Kate McKinnon on SNL NOUS R US Lewis’ March: Book Three Wins NBA for Young People’s Lit Entertainment Weekly’s Validation of Comics Last Gasp’s Last Gasp DeFalco To Write Reggie Book for Archie Playboy Continues to Fail 24-Hour Post-Election Turnaround at South Park Magazines That Jumped the Gun with Hillary Win? Resist! Another Sign of Trumpery Times Charlie Hebdo Goes to Germany Zunar Keeps On Turkey Suppression of Free Speech and Cartoonist Odds & Addenda Image Two-bit Books Barney Google Back Again Bob Dylan and Muhammad Ali Nobels

KRAZY BIOGRAPHY ARRIVES

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of First Issues of—: Frank Cho’s Skybourne Terry Moore’s Motor Girl Second Looks at—: Moonshine Cage Shipwreck Betty & Veronica Also—: Resident Alien 3 Lady Killer 3 Kill or Be Killed 3/4 Renato Jones: The One % 5 Sex 32 Prez ends in Catwoman Election Night No.1

EDITOONERY Postponed until Next Time, but—: Political Magazine Covers Barry Blitt All Over

THE FROTH ESTATE Trump’s Conflict of Interest: Get Over It The Trumpet Lied 560 Times

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Review of—: Stuff They Wouldn’t Print (2010) The Editorial Cartoons of Lee Judge

RANCID RAVES GALLERY 40TH Anniversary Cartoons at In These Times Telnaes Wardrobe Fanboy Head Exploding Bracket

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Interesting Happenings in the Funnies Brad and Toni’s Wedding

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST The Bundys and the Sioux

XMAS SHOPPING LIST Reviews of Books Your Spouse Can Buy You for Christmas—: She Changed Comics: Untold Story of Women Who Changed Free Expression in Comics The Incredible Herb Trimpe Extra Cheesy Zits Alamo All-Stars: A Texas Tale The Lost work of Will Eisner Tim Tyler’s Luck: 1934 (Alex Raymond’s debut) Krazy Kat: 1934 Step Aside, Pops Jack Cole’s Deadly Horror

BOOK REVIEW Super Weird Heroes: Outrageous But Real!

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEWS Black Dahlia (Rick Geary) Strange Fruit Trump: A Graphic Biography (Ted Rall) The Fun Family (satire of Bil Keane’s The Family Circus) The Funnies (prose novel) Cousin Joseph (Feiffer) Citizen 13660 (Japanese Internment, 1942-45)

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Painted Portrait of Charles M. Schulz, c. 1999

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Why I Don’t Fear the Forthcoming Trumpery Administration PASSIN’ THROUGH Robert Webber Jerry Dumas

A George Booth Christmas Annual Report: November 2015 - October 2016

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

JUST ANOTHER LAST WORD ON THE ELECTION The best by far reaction and response to Trump’s victory took place on “Saturday Night Live” on November 12, the first post-election broadcast, when Kate McKinnon sat at the piano in what I take to be her Hillary persona and played and sang: I heard there was a secret chord That David played and it pleased the Lord. But you don’t really care for music, do ya? Well, it goes like this— The fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift, The baffled king composing Hallelujah (five times).

Maybe I’ve been here before. I’ve seen this room and walked the floor. I used to live alone before I knew ya. I’ve seen your flag on the marble arch And love is not a victory march— It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah (five times). I did my best; it wasn’t much. I couldn’t feel so I tried to touch. I told the truth: I didn’t come to fool ya, And even though it all went wrong, I’ll stand before the Lord of song with nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah (seven or eight times).

Then she stopped playing and turned to the camera and said, mildly defiant: “I’m not giving up, and neither should you.”

Until her closing remark, it could be a lament. And it was. But it was more.

And it made me weep.

Ironically, Leonard Cohen, the writer of these lyrics, “Hallelujah,” had just died, November 7, the day before Election Day.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

LEWIS’ MARCH WINS “This is unreal!” shouted Congressman John Lewis as he and his co-creators writer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell accepted the 2016 National Book Award (NBA) for Young People’s Literature for March: Book Three (Top Shelf, 2016). The title is the third in a graphic memoir that chronicles the civil rights movement from the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963, to the passing of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965. But—an award for Young People’s Literature? Why Young People? Is it because graphic novels are glorified comic books, and comic books are for young people? Probably. But I don’t think the March trilogy was written expressly for young people. I think it was written for everyone, regardless of age. I know: a carping criticism. Don’t look gift horseflesh in the maw. Accept your fate. But Lewis didn’t. He didn’t accept his fate. “There were very few books in our home,” Lewis recalled in accepting the award. He also told of going to his public library to get a library card, only to be told that libraries were “for whites.” Despite this, Lewis was still encouraged by his elders to “Read my child, read,” he said. Aydin, digital director and policy adviser for the Congressman, as well the March trilogy’s co-author, reminded the audience that the “story of the movement must be told.” Lewis, who as a young man was directly involved with the Freedom Vote in 1963 in Mississippi, was convinced to tell his story in a graphic format by Aydin. A big fan of comic books, Aydin proclaimed at the close of his acceptance, “Prejudice against comic books must be buried once and for all.” Hear, hear. Two days later, back in Nashville, Tennessee, which Lewis calls the first city he ever lived in, the Congressman was interviewed by Margaret Renkl on behalf of the Nashville Public Library Literary Award, which Lewis was on hand to receive the next day.

Margaret Renkl: Back in your student days, when you were being arrested repeatedly for working to integrate restaurants and movie theaters and the rest of daily life here, what would you have said if someone had told you that one day you’d be back in Nashville to accept a prestigious award for your work as an author? John Lewis: I would have said, “You’re crazy. You’re out of your mind. You don’t know what you’re talking about.” I feel more than lucky—I feel blessed to come back here. I’m honored, I’m gratified, I’m pleased. Asked about how he thinks the Black Lives Matter organizers feel about his generation of leaders, Lewis said: “I think the Black Lives Matters generation tends to admire and embrace what we did. I have had the opportunity to sit down and meet in Atlanta—and also in Washington—with many of the young people, and I tell them all the time, ‘Read the literature, read the papers and books and speeches from that period. You could learn something.’ And I tell them that we never became bitter. We never became hostile. We believed in the way of peace, the way of love—we believed in the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence. I say, ‘You can learn something from the 1960s.’ And that’s what I tell them each and every time I meet with some of them.” Does he have any advice for American children? “Yes. I would say, ‘Children, read. Read everything. Learn as much as you can learn. Study. Be kind. Be bold. Be courageous. And just go for it.’ As I write in the book, my mother and father and grandparents and others said, ‘Don’t get in trouble. Don’t get in the way.’ I was inspired to get in trouble, and I got in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble. People like Rosa Parks and Dr. King and Jim Lawson and others—and being in Nashville—helped mold and shape me, and I have not looked back since.” Margaret Renkl: In the March trilogy, the story of your history is framed and punctuated throughout with scenes from your experiences on January 20, 2009—the day of Barack Obama’s first inauguration—and it includes a note signed by President Obama: “Because of you, John.” What are you thinking as you watch his presidency come to an end after eight years? John Lewis: It’s difficult to see it come to a close because I think President Barack Obama has injected something rare and meaningful into America, and it’s going to be missed. I see him from time to time; I listen to him by way of radio, TV; I read about him and each time he seems to be hopeful and optimistic. And that’s what we need more than ever before. I think he’s been good for America. He’s been good for the world community. On one occasion, when he was running for reelection, I said, ‘Mr. President, if you were running for reelection in Europe, you wouldn’t have to campaign. You’d win by a landslide.’ I’ve traveled to different parts [of Europe], and the people there love him.” Reported by Rocco Staino at slj.com

THE ULTIMATE VALIDATION OF COMIC BOOKS Now that the movie business has established the cultural worth of comic books for everyone except the National Book Awards, Entertainment Weekly has begun to pay attention to more than just the summer extravaganza in San Diego. In the December 2 issue (with a cover story about the next Star Wars movie), a new funnybook by “two of the most exciting comic-book creators, Scott Snyder and Jeff Lemire” is fulsomely plugged. A.D., “a compelling mix of comics, art and storytelling,” is a “beautiful new series that explores a world in which death has been eliminated.” Another title in a lengthening roster of good comics—well drawn and well told in a blend of words and pictures—on mature (i.e., thoughtful) themes. And comics even intruded in EW’s year-end “Best of 2016" issue, December 16/23. “Entertainer of the Year” is Ryan Reynolds —for his portrayal of smart-ass potty-mouth Deadpool, no less. And Benedict Cumberbatch is among the other top twelve “entertainers of the year” for his Dr. Strange as well as Sherlock Holmes. Among

the year’s best movies, “Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice” is listed because

of the way breakout actress Gal Gadot plays Wonder Woman. And “Captain

America: Civil War” is tenth in the top ten movies of 2016. This commemorating issue even lists the Best Comic Book series of the year—Black Panther (Best New Series), Bitch Planet (Best Returning) DC Comics Rebirth series (Best Reboot), Monstress (Best Ongoing), and Goldie Vance (Best All-Ages). But there’s no “best graphic novel”category. Finally, in reporting the reading recommended by various entertainment dignitaries (Emma Watson, J.K. Rowling, Stephen King and Kerry Washington among others), the magazine cites Sarah Jessica Parker, who recommends Tintin in Tibet by Herge. But I don’t want to give up on EW’s best of the year without pausing to note that the magazine recorded the “most bizarre auction item”—Truman Capote’s cremains, which, “ensconced in a wooden Japanese box, sold for $43,750.” Ewww. Further evidence of EW’s allegiance with the comic book world, subscription renewal forms that arrived last month offered a bonus for subscribing by December 3—superhero t-shirts featuring (your choice) the Flash, Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman or Super Friends. Talk about uptown: we’re there! Stick that in your ass, National Book Awarders.

LAST GASP’S LAST GASP (Couldn’t resist that headline.) According to Milton Gieppe at ICv2, “Last Gasp has announced that it is closing down its distribution business, which has wholesaled comics, graphic novels, art books, and other publications for 47 years. The distribution business rose out of Last Gasp’s roots as a publisher of underground comics, which were sold through a network of bookstores, head shops, record stores, and eventually comic stores. Last Gasp used that network to sell not only its own comics, but those of competing publishers, and added to its mix books and occasionally magazines that fit the same audience.” The company will now focus exclusively on its publishing endeavors “for which it has many new titles planned for 2017.” Meanwhile, my guess is that we should keep a sharp eye out for a bargain-hunter’s sell-off of the publisher’s remaining inventory.

SURPRISE: SUPERHEROIC REGGIE AT ARCHIE COMICS At CBR, Jeffrey Renaud reminds us that “as a writer and editor, industry legend Tom DeFalco has told stories with heavyweight heroes ranging from the Amazing Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four to G.I. Joe and the Transformers. So when he calls Reggie Mantle a ‘sinister super-villain,’ you might want to pay attention.” What prompts this cautionary note is that DeFalco is going to be writing a new on-going series at Archie Comics—namely, Reggie and Me, about Archie’s presumed rival. The first issue hit the stands on December 7, illustrated by Sandy Jarrell, Kelly Fitzpartrick, and Jack Morelli. DeFalco started his career at Archie, so he’ll be coming “home” in some sense. Renaud asked him several impertinent questions about the new Reggie book, and DeFalco responded in kind. About Reggie, DeFalco said: “Classic Reggie was a prankster, but he was always rather harmless. He was also one of Archie’s friends, and a member of the gang. The current Reggie is an outsider. Yes, the other guys want to be like him and the girls want to be with him, but he is no longer a member of the gang.” Renaud: You say he’s one of your favorite characters. You admit that he’s been called a self-aggrandizing egotist, a sinister super-villain, a merciless monster and worse. So — what’s to love? DeFalco: What’s not to love? He drives the best cars and throws the wildest parties. He is also the closest thing Riverdale has to a supervillain and everyone loves a great villain. Renaud: Is Reggie Mantle misunderstood? DeFalco: Absolutely! A lot of people assume he has some redeeming characteristics. [Laughs] Renaud: Can you confirm today that the ‘me’ of Reggie and Me is in fact Reggie’s dog, Vader? DeFalco: I could, but why spoil the surprise? Renaud: Will you be telling done-in-one stories in Reggie and Me or will the stories be longer arcs? DeFalco: I will be doing both. Every individual issue will be a done-in-one, but the stories will build upon each other to form larger arcs. I never make life easy for myself. Renaud: What can you tell us about the first story that you have planned? DeFalco: Reggie throws a party and things go sour for everyone… except Reg. Also, we learn the not-so-secret origin of Vader.

PLAYBOY CONTINUES TO FAIL The December

issue is out, and it actually has two cartoons in it. Simple scrawls, both of

them, scarcely in the same I got my renewal notice last week. I sent it back, annotated: “Not until you start publishing good cartoons again.”

MAJOR KERFUFFLE AT SOUTH PARK WHEN HILLARY LOSES “South Park” famously creates each episode within a week, as chronicled in the 2011 tv documentary “Six Days to Air.” In 2008, as Michael Cavna reports at Washington Post Comic Riffs, the show impressively turned around the episode “About Last Night .?.?.” to react to Barack Obama’s first presidential win, less than 24 hours after it was official. And this year, they did it again. In what Cavna thinks might be “South Park’s” best single-day rewrite ever, the Clintons and the show’s Colorado denizens absorb the nation’s presidential results just hours after real-life Hillary Clinton conceded. Wednesday night’s episode, as originally written, was to focus on Bill Clinton’s becoming the first First Gentleman. But Donald Trump’s poll-defying victory forced creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone to scramble at the 11th hour, changing the episode, retitled “Oh, Jeez,” to reflect at least half the nation’s blindsided surprise and electoral mourning. In the show’s trademark style of paper-cut animation (so crisply digitally rendered), mouths are agape all over South Park, as the Marsh family and their neighbors sit in awkward and dumbstruck silence, as it witnessing a national car crash. At one point, papa Randy Marsh declares: “A woman can be anything — except for president.” Three characters who remain in full-action mode, though, are Hillary and Bill Clinton and the show’s Trump avatar during the season-long election arc, schoolteacher Mr. Garrison. Two true villains in all this, according to “South Park,” are sexism and the mind-numbing allure of nostalgia. Hillary ostensibly drafts super-troll Gerald for an international plot to stop the world’s most damaging online-leaks fallout. Meanwhile, her husband drafts a fellow Bill, Cosby, into his “gentlemen’s club,” spreading the message that women are growing sick of male misbehavior (and worse) and will eventually topple the patriarchy, rendering men (mostly) irrelevant and sentencing them to subterranean confinement.

SNAFU BY JUMPING THE GUN? Even after Donald Trump was actually elected on November 8, reported Alex Johnson at NBC News, Newsweek published 125,000 copies of a $10.99 commemorative magazine with Hillary’s picture on the cover and the headline "Madam President." Were they simply anticipating what would happen (according to all the polls)?—as the Chicago Tribune famously did in the 1948 Election when it decided that Tom Dewey won and headlined the post-election issue accordingly; and when Harry Truman won, he held that edition of the newspaper aloft with a huge grin on his face. The “Madam President” copies were quickly recalled — but hundreds of these “collectors’ dream” copies are still being offered for sale in online markets, “for prices as low as 99 cents to as high as $9,995. NBC News found 387 offers for the recalled issue Wednesday evening just on eBay.” The publisher maintains that only 17 copies were actually sold before all the rest were recalled, bringing into serious question the authenticity of many of those online offers. Newsweek itself distanced itself from the "Madam President" edition when news of it emerged even before Election Day, saying on Twitter that commemorative covers were produced for both Clinton and Trump "by a Newsweek licensee, Topix Media, and not by Newsweek." But whoever is responsible—and even if the Clinton cover story wasn’t actually a prognosticating gamble gone awry like the Chicago Tribune’s 1948 laughable forecast—we get to enjoy two covers for two cover stories, knowing only one is accurate. Worth a chuckle. Pictures of the covers are on the other side of the $ubscribers Wall, where we also post some wag’s deployment of the New York Times masthead for a little cartoonish fun—cartoonish because the pictures explain the words in the headline. Good joke. And

we also have some wag’s deployment of the New York Times masthead for a

little cartoonish fun—cartoonish because the pictures explain the words in the

headline. Good joke. And

while we’re pondering this sort of two-faced prophesying, here are two by Daryl

Cagle, editoonist and head of a distribution syndicate for dozens of other

editoonists. At the top, we have Cagle’s first thoughts about the results fo

the Election; then, when Hillary didn’t win, he quickly revamped the cartoon,

switching heads for the second version just below the first. Said Cagle: “Hillary is a blue dragon now [slain Democrat]. I gave her dead ‘x-eyes’ replacing the bloody sword so that she wouldn’t have ‘blood coming out of her whatever.’ “I

had a lot of good company among my cartoonist colleagues,” he continues,

writing at his syndicate headquarters on the day after the Election, “—in fact,

we faced a bit of a crisis this morning as no cartoonists had drawn Trump Wins

cartoons in advance. But “I suspect that we’ll be in for four years of the same,” he concluded. “We’ll certainly see Trump hair placed on every imaginable monument and metaphor,” he concludes, accompanying the remark with another cartoon.

ANOTHER TRY AT FEMALE EMPOWERMENT FAILS Wonder Woman's less than two-month reign as a United Nations honorary ambassador ended December 16. According to Sebastien Malo at news.trust.org, plans had called for use of the character in an empowerment campaign for women and girls to fight for gender equality, especially to appeal to young people. But the plan “sparked heavy criticism that the choice sent the wrong messages.” (See Opus 359 for the story.) Dozens of U.N. employees protested on the day of the appointment. And nearly 45,000 people signed an online petition asking U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to reconsider selection of the buxom character. "Although the original creators may have intended Wonder Woman to represent a strong and independent 'warrior' woman with a feminist message, the reality is that the character's current iteration is that of a large breasted, white woman of impossible proportions, scantily clad in a shimmery, thigh-baring body suit," the petition read. Release next year of a special-edition Wonder Woman comic book on the empowerment of women and girls, announced in October, is still planned, said DC Entertainment spokesperson Courtney Simmons.

ANOTHER SIGN OF THE TRUMPERY TIMES A couple of Spiegelmans are collaborating on an anthology of comics and illustrations “on the theme of political resistance to the forces of intolerance,” reports Gabe Friedman at jta.org. Entitled RESIST! and produced by Nadja Spiegelman, 29, daughter of the famous holocaust Maus man, Art, and his wife, Francoise Mouly, art editor of The New Yorker, the publication is “fervently anti-Trump.” A special issue of Gabe Fowler’s “quarterly tabloid comics anthology” Smoke Signal, 30,000 copies of which will be distributed for free in Washington, D.C., on Inauguration Day in January. More copies will be given away at women’s marches across the country in the days after. Submissions of cartoons and illustrations— including some from big names like Roz Chast — have exceeded Spiegelman fils’s expectations: 500 in the first week. ... While the initiating concept of the project was to give female voices an opportunity to react to the election of the Trumpet, some illustrations also tackle anti-Semitism, and the phrase “RESIST the normalization of fascism” appears at the top of the website’s “about” page. One

image references Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp” of political insiders in

Washington, showing Hitler’s face emerging at the bottom of the swamp as the

water is drained away. “We’ve clearly hit a nerve,” Spiegelman said. “There’s such a need that people have, especially artists, to find ways to begin to pick up a pen and fight against this. Now more than ever we do need to use our voices and make them as loud as possible.” The concept originated with Fowler, who runs the Desert Island comics store in Brooklyn, where he produces his quarterly comics publication. He decided to have an issue edited by women. He reached out to Mouly and asked her to head the project; she subsequently asked her daughter to help. At first, the idea was to accept only submissions from women and focus on women’s issues. The team has since broadened its scope: they are accepting submissions from men as well, but issues of female concern remain a dominant theme. Spiegelman said it was interesting to separate the submissions by gender — the female artists tended to include drawings of women, while the male artists tended to include an image of Trump. Spiegelman said she hasn’t received any of the online anti-Semitic abuse coursing through Twitter in recent months. But her mother received some hate mail after publishing a New Yorker cover that criticized Trump’s intention to build an impenetrable wall on the border with Mexico. [We’ve reproduced that cover in our Editoonery department.—RCH] Said Spiegelman: “She forwarded it to the rest of the family, saying ‘Wow, I must be doing something right!’”

CHARLIE GOES ABROAD The first German edition of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo arrived on newsstands December 1, nearly two years after an attack on the publication’s headquarters in Paris killed top editors and cartoonists, ostensibly because they insulted Islam. The German edition is a response to significant German interest in Charlie Hebdo after the attack, editors told Charly Wilder at the New York Times. “It’s an experiment,” Gérard Biard, Charlie Hebdo’s editor in chief, who added that the paper had been the subject of numerous exhibitions, awards and news coverage in Germany since the attack on January 7, 2015. With an initial print run of 200,000, the new edition will be available across Germany every Thursday. It will consist mostly of translated material from the French version, but with some original content for its German readers. The first cover, Wilder reports, depicts a worn-out-looking Chancellor Angela Merkel lying on a hydraulic lift, with a caption saying that the embattled German carmaker Volkswagen “stands behind Merkel” and that “with a new exhaust pipe, she’ll be good to go for another four years.” The editor of the German edition, who uses the pseudonym Minka Schneider, said, “Germans feel particularly close to France and to Charlie Hebdo, and the debate about freedom of expression is very passionate here compared to other countries.” The first German issue, with 16 pages, features a four-page travel feature by the cartoonist Laurent Sourisseau, who uses the pen name Riss, depicting people he met across Germany and their thoughts on cultural heritage, national identity and the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees, most of them Muslims, in the last several years. The reaction in the German news media has largely been positive, with a few exceptions. “I don’t believe that magazine will go over well in Germany,” said Martin Sonneborn, a former editor of Titanic, a satirical magazine, “because it has such a specifically French aspect and represents a very unique type of humor.” Charlie Hebdo’s brand of satire tends to be harsher and darker than German counterparts like Titanic and Eulenspiegel, said Wilder. The editors acknowledge the challenge of appealing to a German audience but said the timing of the new edition was opportune. “Germany is facing problems today that France already faced a few decades ago, like immigration and the banlieues,” Schneider said, referring to the heavily immigrant neighborhoods that ring many French cities. “So maybe learning something about French society can help the Germans, and humor is a good way to do this.” If Charlie Hebdo is less concerned about causing offense than are most German publications, that may be a good thing, Biard suggested. “In Germany, you hear about the Lügenpresse a lot,” he said, referring to a Nazi-era word meaning “lying press” that has been taken up in recent years by far-right protesters accusing the mainstream German news media of dishonesty. “I think no one can say to Charlie Hebdo that we’re all politically correct. We don’t think, ‘Oh you cannot say this in Germany, you cannot do this.’” “Everybody can be a subject in Charlie Hebdo,” Biard continued. “So we feel pretty free to have a look at German society.”

ZUNAR KEEPS STANDING UP The Malaysian cartoonist Zunar (Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque) can’t stay out of trouble. And even when he stays out of trouble he gets in trouble. When protesters disrupted an exhibition of his cartoons in late November, he was arrested. Not the protesters. Zunar was questioned by the police, detained for a day and informed that he was under investigation for producing cartoons that purportedly defamed Prime Minister Najib Razak. It was not the first time Zunar, who already faces nine charges of sedition and is barred from leaving the country, has courted trouble with his pen. His cartoons frequently target Najib, who is accused of taking millions of dollars from a state investment fund. Najib has faced widespread calls to resign, most recently at an anticorruption demonstration this month that drew tens of thousands in Kuala Lumpur, the capital. Zunar

was interviewed by Mike Ives of the New York Times just after the

incident. One of the things they talked about was the cartoon we’ve posted near

here. “It’s a self-portrait,” Zunar said. “In it, you see that three laws have been used against me. First is Sedition Act, second is Penal Code, third is Printing Presses and Publications Act. I was chained with these laws — hand, neck and leg. But if you go to my shirt, you can see my philosophies there. Among them are ‘I will keep drawing until the last drop of my ink’ and ‘How can I be neutral … even my pen has a stand.’ So this drawing shows that even though there’s a law to stop me, even though there’s a regulation to stop me, even though they tried to ban my books — actually, not tried, they already banned my book — I will keep drawing. That is why, without hands, I still use my mouth or my teeth to draw. This is to show the philosophy and determination to fulfill my duty as a cartoonist in Malaysia.” Zunar is expecting a tenth sedition charge, but even without it, he faces upward of 40 years as a maximum prison sentence if he’s convicted. How does he feel about it? “You have to understand this is a politically motivated charge; it’s got nothing to do with the law,” he said. “In Malaysia, it’s very, very difficult for us with politically motivated charges. You just need to look at what happened to the opposition leader’s case in Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim. Even though he had strong evidence and witnesses, it was political. It will be very difficult for us to fix that. But this is a very important case for me to create awareness around the world about the state of freedom of expression and human rights in Malaysia. I’m going to face it.”

AND IT’S WORSE IN TURKEY In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been cracking down lately on opposition throughout the country in the wake of a failed coup attempt several months ago. Tens of thousands of alleged coup collaborators have been jailed or fired from their jobs. “A failed coup is a great excuse to get rid of everyone Erdogan doesn’t like,” said editoonist/syndicate mogul Daryl Cagle in reporting the story—whether they were involved with the coup or not. “Virtually all of the media outlets that have been critical of him have been closed down. The only opposition paper left, Cumhuriyet, was raided last week with their editors, their top writers and their editorial cartoonist thrown in jail.” The

cartoons of Musa Kart have enraged Erdogan for years. Erdogan tried to

put Kart in jail for nine years for the 2014 cartoon (seen on the left in our

visual aid) that depicts a money laundering scandal as a hologram of Erdogan

looks the other way. “How will they explain this to the world? I am being taken into custody for drawing cartoons. I’ve been trying for years to turn what we’re living through in this country into cartoons. Now I feel like I’m living in one.” A 2005 cartoon (on the right in our exhibit) shows Erdogan entangled in strings. Kart was tried and sentenced to prison, “but his penalty was reduced to a fine, and the courts later dismissed the fine,” Cagle said. Hundreds of protesters camped overnight at the Istanbul headquarters of Cumhuriyet in support of the paper as the last symbol of freedom of the press. About the closing of news outlets, Christophe Deloire, secretary-general of Reports Without Borders, said: “Cumhuriyet is once again the target of persecution, another 15 media have been closed and there is hardly anyone left to cover this. ... If turkey does not stop using the state of ermergency to kill off media freedom, it will soon be too late. At this rate, media pluralism will be a distant memory before long. Are people sufficiently aware of the dramatic change taking place in this country, where no media outlet seems to be safe from this never-ending purge?”

Cagle, whose syndicate distributes editoons by cartoonists from all over the world, said cartoonists everywhere are sharing drawings in support of a free press. Here, to conclude this report, is one by India’s Paresh Nath, one of Cagle’s roster.

ODDS & ADDENDA Image Comics will celebrate 25 years as a comic book publisher next year, and it’s giving its fans a little gift, reports George Gene Gustines at the New York Times. February issues of The Walking Dead, Invincible, and Outcast, each written by Robert Kirkman, will cost only a measly two bits, just 25 cents (25 years; 25 cents). “The stories in these issues will be a good jumping on point for readers” Gustines said: “The Walking Dead No.163 follows the conclusion of the Whisperer War; Invincible No.133 begins ‘The End of All Things,’ a 12-part story that will conclude the superhero series; and Outcast No.25 will introduce characters to the series about demonic possession.” Barney

Google, who was written out of his own comic strip (although not out of the

title) years ago after Fred Bob Dylan didn’t make it to Sweden to pick up his Nobel Prize for Literature: ol’ sourpuss stayed home and stewed in his continually reinvented mysteriousness. But the whole Dylan-Nobel fiasco prompted a Faux News enterprise to post this headline and story: Muhammad Ali Posthumously Awarded 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature as author of the immortal lines “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” I’m going to look into Dylan’s poetry a little over the next few weeks; report next time.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO “If you cannot teach me to fly, teach me to sing.”—J.M. Barrie

THAT KRAZY BIOGRAPHY OF THE KAT’S KREATOR The long-anticipated biography of George Herriman, creator of the comic strip masterpiece Krazy Kat, is now awaiting your purchase on the shelves of the nation’s bookstores. Said Doug MacCash at NOLA.com Times Picayune, “Krazy: A Life in Black and White, the biography of the Crescent City-born newspaper cartoonist is an absorbing study of a genius with a secret. ... As New Orleans author Michael Tisserand deftly points out in his 549-page volume, the illogic of Herriman's ink-on-paper drawings mirror the absurdity of the racial divide in early 20th-century America.” Herriman’s secret, Tisserand says, is that he was black passing for white. MacCash continues—: After 10 years of scouring microfilm archives, yellowed newspapers and public records, Tisserand has pieced together Herriman's journey from his humble birth in the Treme neighborhood to heights of fame in Jazz-era New York and Los Angeles. Like a snake handler, Tisserand uncoils the confusing racial politics of New Orleans in the Jim Crow era, where the descendants of slaves and the descendants of so-called free people of color suffered segregation, discrimination and violence at the hands of the white population. As Tisserand explains, when Herriman was 10 years old, his parents fled the South for a new beginning in California, where personal reinvention was possible. Tisserand writes, "Herriman was a black man born in New Orleans." But upon reaching the Pacific, Herriman's parents "had obscured their identity and 'passed' for white." Had they not done so, Tisserand points out, the creator of the immeasurably influential Krazy Kat cartoon could never have received the classical education that he did, found work in major American newspapers, or bought a home in the Hollywood Hills, owing to universal racism. ... About midway through the book Tisserand delightedly introduces Herriman's masterpiece, a blithely bewildered black cat that is routinely abused by a brick-throwing white mouse. More than a century after his first appearance, Krazy Kat remains an enigma. "It's in Krazy's language that Herriman achieved what I think he was going for more than anything else," Tisserand said, "which is a sort of depiction of the entire rude, wonderful American character. It all mixes together in the language; one sentence can have German, French, Creole, Yiddish, you know, highbrow English, lowbrow English, and newspaperman slang, all jumbled together." Herriman's Krazy Kat strip, which appeared from coast to coast, allowed him to subtly comment on the superficiality of race, as the animal characters occasionally swap colors. ... Herriman was much beloved by his fellow cartoonists, intellectuals, and modern artists, but, Tisserand points out, his cartoon was always near the bottom of reader popularity polls. Its survival for three decades in the cutthroat early 20th-century newspaper business is as much a mystery as the goings-on in the strip itself. But, like a true artist, Herriman never backed away from his peculiar vision. "His work is unflinchingly uncompromising," Tisserand said. "He never seemed capable of doing anything less than bringing everything he had to the work, whether it's a literary allusion that most readers wouldn't catch or whether it's a visual allusion to a Navajo rug. He would do what he wanted, even if he knew, 'Boy, readers are not going to connect with this.'" Bravo to Tisserand for helping us connect. It's an amazing accomplishment to uncover so much information about a cartoon that the public has largely forgotten, in a style that's hard to describe, by a man that needed to keep his background in shadow. Speaking of Herriman's paradoxical legacy, Tisserand said: "I think he succeeded in creating a comic strip that reflected the way he viewed the world. It's delightful and sad and filled with unconquerable love and lots of bricks to the head." The HarperCollins hardback with a 16-page photo section went on sale December 6 for $35. Below, find an excerpt from the book that illuminates Herriman's influence on contemporary comics (in italics): No book collections of the strip Krazy Kat were published in Herriman's lifetime. By the time of his death, most comics pages had been discarded, or were disintegrating in garages and basements across the nation. Herriman's originals piled up at King Features, where young cartoonist Mort Walker once noticed that they were being used to sop up water leaks. Yet when one influential fan heard the news of Herriman's death, he determined that Krazy Kat would not be forgotten. Poet E. E. Cummings contacted his publisher, Henry Holt and Company, to propose that he collect and edit a volume of Krazy Kat comics, as well as write the introduction. [Social and literary critic] Gilbert Seldes was delighted to hear the news. "I am extraordinarily glad that you are going to do this," Seldes wrote to Cummings in the fall. "May I place at your disposal my ancient and incomplete collection of these masterpieces, and give you also whatever clerical or other assistance I can." The next year [1946], Henry Holt published Cummings' Krazy Kat, announcing that the comic strip "had been away from the papers for some time now," and that it was "something for Americans to be proud of." Cummings' book featured 168 strips, each selected by the poet. In his introduction, he described a "meteoric burlesk melodrama, born of the immemorial adage love will find a way." Cummings wrote of Krazy as a "humbly poetic, gently clownlike, supremely innocent, and illimitably affectionate creature," understood by Officer Pupp and Ignatz no more than the "mythical denizens of a two-dimensional realm understand some three-dimensional intruder." Cummings added new interpretations to Herriman's work, likening Krazy to the democracy's "spiritual values of wisdom, love, and joy" and Pupp and Ignatz to "those red-brown-and-blackshirted Puritans." With that, he joined would become a large chorus of writers, artists and academics seeking to limn the mysterious devotions of Krazy, Ignatz and Pupp. Cummings' anthology, while not a commercial success, became a coveted treasure for fans [I found my copy in a used bookstore in Richmond, Virginia, a generation ago; it was a fond early acquisition in reprint tomes that has since grown to fill a basement—RCH], and its influence ran deep. Most significantly, Cummings' book fell into the hands of a young Midwestern cartoonist, just returned from military service. "After World War II, I began to study the Krazy Kat strip for the first time, for during my younger years I never had the opportunity to see a newspaper that carried it," recalled Charles Schulz. "A book collection of Krazy Kat was published sometime in the late 1940s, which did much to inspire me to create a feature that went beyond the mere actions of ordinary children." In Peanuts, Schulz drew deeply from Herriman's themes of love and loss, and sin and guilt. He created a world as devoid of adults as Coconino County was devoid of humans. Whether by intent or coincidence, there even were direct borrowings. Cummings' collection included a series, originally drawn in 1934, showing Krazy, Ignatz and Pupp seated on a log, patiently waiting for the last "ottim liff" to fall. [See the review of the IDW reprint volume at Xmas Shopping List down scroll.—RCH] Schulz revisited this storyline frequently, drawing a leaf hanging onto a branch for dear life, or circling in mid-air for one last fling before the rake. In later comics, Schulz even wrote a series of gags in which a school building tosses a brick. Of all of Schulz's storylines, Lucy's relentless, obsessive football prank most suggested Ignatz and his brick. In fact, a Krazy Kat series, first published in 1932, shows Ignatz tying a string on a football, and then pulling it away when Pupp runs to kick it. Pupp, like Charlie Brown after him, lands squarely on his back. In a conversation with Mutts cartoonist Patrick McDonnell, Schulz acknowledged that even Herriman's Navajo-inspired zig-zag designs seemed to find their way onto Charlie Brown's iconic shirt. Schulz would honor his inspiration when he penned a drawing of Charlie Brown wandering onto the Coconino desert and getting beaned by Ignatz. Said Schultz: "I always thought if I could just do something as good as Krazy Kat, I would be happy. Krazy Kat was always my goal."

Fitnoot: The foregoing is a tantalizing look inside the book, which I haven’t otherwise seen, a situation that is already on its way to being remedied; I ordered the book several months ago. While I must wait until I have read the book before proclaiming a thorough-going opinion about it, a couple of intimations in the advance notices and interviews with Tisserand leave me a little testy (alas). First, I’m afraid that Tisserand is going to make too exact a connection between Herriman’s life and his comic strip: in the fashion of David Michaelis’ Schulz biography (which Tisserand admires), Tisserand may find the strip not an echo but a parallel of Herriman’s life. This is the kind of mistake made by people who are not intimately familiar with the cartooning medium and how cartoonists think—and Tisserand has no previous credentials in this area. Simply put, the art of cartooning is not autobiographical. And we must wait to see to what extent Tisserand understands this. Secondly, I’m leery of any argument that sees Krazy Kat as some sort of allegory about race in America. Many of the interviews and articles about the book have stressed this connection, but that may be a consequence of the “news” media’s proclivity for promulgating sensation, and while most of us have long ago realized that Herriman was of African descent, the general population, readers of the advance notices about the book, may not, and so the news media heaps up a “fresh” sensation to attract readers/consumers/viewers. To see Krazy Kat as a race tract does as much violence to the arts of cartooning as to see it as the cartoonist’s autobiography. In the last analysis (which I won’t perform until I’ve read the book), it’s a question of emphasis. It remains to be seen whether Tisserand has fallen into the error of this way or not. If he does—or if he successful navigates this, the trickiest part of his course, without making this mistake—I’ll tell you. I’m sure, however—based largely on the passages quoted above—that the book will be a rich trove of information about race in America during Herriman’s early life in New Orleans and in Los Angeles. For that alone, the book is to be applauded. In another article that surfaced lately among the flood of Krazy book pieces, Tisserand asks rhetorically why Mickey Mouse wears white gloves. Mickey and several other comic characters in the early years wore white gloves, and Tisserand theorizes that the minstrel shows of that era, still a vibrant part of America’s entertainment scene, inspired this wardrobe accessory. Many minstrel shows (perhaps most) featured white performers in blackface, imitating African American characters. And they wore white opera gloves—probably because wearing gloves made it unnecessary to blacken their hands. From this gloved kinship between comic strips and minstrelsy, Tisserand concludes that early strips were, in effect, offshoots of minstrel shows. A happy discovery, surely. But how accurate is it? There’s little question that minstrelsy influenced comic strips—and all American humor—for a time. Sometimes indelibly: that brick Ignatz throws at Krazy? It’s pure minstrel show—another version of the pie-in-the-face comic put-down stagecraft. And Herriman may have borrowed the maneuver from other strips, too: Mutt and Jeff often ended with Mutt hitting Jeff with a brick or some other equivalent of a custard pie. The white-gloved Mickey Mouse may have distant connections to minstrelsy (it’s such a great idea I’m ashamed to shortchange it), but I think there are other more mundane explanations. When Mickey first appeared in “Plane Crazy” and in other early performances, he isn’t wearing gloves. The gloves arrived (according to an online Guardian article) in “The Barn Dance” (1928) or “The Opry House” (1929). And here’s Walt Disney’s explanation for the gloves: “We didn't want him to have mouse hands, because he was supposed to be more human. So we gave him gloves. Five fingers looked like too much on such a little figure, so we took one away. That was just one less finger to animate.” “A very down-to-earth approach,” says Rolf Harris, who wrote the piece. “And if you put gloves on a cartoon character, you don't have to animate all those wrinkles and lines. Incidentally, there's a similar evolutionary path that can be traced to the emergence of Bugs Bunny's gloves in “A Wild Hare,” Tex Avery's l94O cartoon that gave us the classic phrase, 'What's Up Doc?'” Today’s lesson? We must be wary of poetic discoveries of this kind. Some are too good to be true, in the well-traveled phrase. And so, nit-picking curmudgeon that I am, I’ll be looking askance at any such poetry that may emerge in Tissserand’s book. Besides, Krazy, for all the vaudeville and minstrelsy in his/her comic strip, didn’t wear white gloves. Or any gloves at all. And Krazy was closer in time to vintage minstrelsy than Mickey.

KRAZY LATE-BREAKING: A day after typing the preceding paragraphs, I received my copy of Krazy. And while I’ve read only the first couple chapters and dipped in and out of some of the rest of the book, I’m happy to say that it appears that Tisserand has avoided the pitfalls I anticipated. He has done stupendous research in tracing the lives of the cartoonist’s family in New Orleans, linking the Herrimans to the free people of color power structure in the 19th century city. And it appears that he has done the same throughout the biography, digging up aspects of the cartoonist’s life that have, until now, been unknown—like Herriman’s ill-fated partnership with fellow cartoonist/artist Walt Kuhn to produce a movie in 1925. I’m sure there will be many more such nuggets of biography awaiting discovery throughout the book. I am disappointed, however, to see so little of Herriman’s comic strips in the book. In fact, there are no complete comic strips on display. None of Herriman’s stunning Sunday Krazy Kat strips. Not one complete daily strip. Individual panels from both Sundays and dailies are sprinkled throughout. But no complete strips. At first, I thought Tisserand was limited by some dictate from his publisher, some facet of copyright law that the publisher was afraid to confront. So rather than arrange costly permissions, Harper Collins opted for mere tokenism rather than full representation. And that brings us to a heartbreaking question: How can Tisserand pretend to examine and appreciate Herriman’s spectacular artistry without looking at some representative strips—complete strips, beginnings, middles and endings? The answer is, Tisserand makes no such pretense. His book is deliberately not about comic strip artistry. On the very first page of the book—the Author’s Note—he tells us of his self-imposed limitations: “the dimensions of this book do not allow for a full presentation of Herriman’s grand comics.” Just biography then? No, there’s a little more. “I have included panels from his works to illustrate certain ideas and to give at least a hint of their splendors.” And so on page 24, we have a panel in which Ignatz, sending a brick to Krazy’s head, exclaims: “You’re now a member of the fraternal brickhood of noble dornicks.” This alludes to Herriman’s father’s involvement with the Masons. Other

individual panels illustrate Herriman’s sensitivity about race and identity and

racial identity—Krazy looking at himself in the mirror, making black coffee

(“look unda the milk”), going to a beauty parlor and coming out blonde. This is sad because Herriman was so much a master of his medium and a pace-setting pioneer. Perhaps Tisserand will do better at a website (michaeltisserand.com), where he promises some of Herriman’s “grand comics” will be posted. (I couldn’t find it, though; maybe it’s not up yet; in the meantime, you could consult Harv’s Hindsight for November 2015, “Krazy Love,” where I offer the kind of analysis and appreciation I’d been hoping to find in Tisserand.) What remains, however—the 545 volume at hand—is a monument to Tisserand’s thoroughness in research and his dexterity in weaving so much of what he found into a fascinating tapestry of Herriman’s life. I look forward to finding more gems like this one: “Herriman began adding more decorations to his comics—especially the sun cross or wheel cross, a design common in southwestern Indian art. The symbol—a cross or X inside a circle—had special appeal to Herriman, for it also resembled the hobo symbol for a friendly household. ...”

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

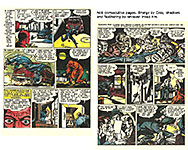

THE FIRST ISSUE of Frank Cho’s Skybourne opens with an unexplained puzzle and continues in the same mode until it ends. The puzzling first three pages take place 29 years ago; they depict a man in modern dress falling from great height, landing in a Chinese field with explosive force, then, prone in the hole his landing has created, opening his eyes and sighing. Nothing in the book explains this strange happening. If we hadn’t read early publicity about the title (see Opus 356 in August), we would not know, as Cho says then, that the falling man is “Thomas Skybourne, an immortal tired of his everlasting life, who goes on a search for a mystic weapon, Excalibur, that could kill him. In the opening sequence, Skybourne is seen falling from the sky (he jumped out of a plane without a parachute), his latest attempt at ending his life.” The

rest of the first issue, which takes place “today,” depicts the attempt of a

combative young woman named Grace Skybourne to obtain the storied sword

Excalibur. She has paid the asking price for the weapon, a medieval Arthurian

relic, but the owner is reneging on the deal. So in this issue’s central

completed episode, she battles him and his minions and takes it from him by

force, displaying her courage, resourcefulness and combat skills. “Force” for

Grace includes jamming her fist through bodies, skulls, buildings. Cho is the consummate comics storyteller. He tells his story here with minimum verbiage, the pages unfolding in almost continuous action sequences, all carefully worked out and exactingly depicted, varying camera distance and angle for the energy of visual variety. In Grace, he has created an intriguing character—strong, seemingly impervious to physical damage but, in the end, skewered to death. Since she appears to be the protagonist of the title, the book’s ending is the cliffhanger of all cliffhangers. And then there’s that cryptic opening sequence. In the second issue (of a scheduled five), we meet Thomas Skybourne (again): after his fall 29 years ago, he’s been living and working in a Chinese monastery, but Cardinal McSwiggin, an old friend and a power in the Catholic Church, comes to convince him to return to civilization to help battle an unknown tragedy looming on the horizon. Skybourne agrees and returns to Mountain Top, the headquarters, where he is tested by means of a physical encounter with a monstrous minotaur. Skybourne fails his test: he can’t get a blow in sideways. At the end of the book, the robed man from the first issue shows up again in a mountain cave where he keeps a dragon pursuant to his plan to take over the world.

There’s a good deal of talk in this issue as an exchange between McSwiggin and Skybourne fills in the many blanks left gaping in the first issue, and we see how skillful Cho is at constructing witty dialogue. We also witness a good amount of action and Cho’s catalogue of visually arresting sequences. Marcio Menyz is given cover credit as the colorist, and in this issue, we see why: he enhances Cho’s linear renditions with many delicately varied hues, modeling the characters exquisitely.

TERRY MORE is off and running again: Motor Girl No.1 is the launch of another graphic novel, which he’ll issue serially in parts before combining the whole thing into a single book like he did with Strangers in Paradise and ECHO and Rachel Rising. The first page introduces us to the rear end of Moore’s protagonist, Sam, a woman mechanic who operates an automobile junkyard, and her assistant, a talking gorilla named Mike. Seems right away to be an echo of Love and Rockets. But it’s not. The opening gambit is a completed episode in which we learn of Sam’s obsessions about the forthcoming end of the world and her wit. In the next completed episode in which Sam’s boss, an old dame named Libby, tells Sam someone wants to buy the yard, we learn that Sam is a vet who’s served three tours of duty, including imprisonment for a year in solitary confinement. And yet she continues to function—with wit and imagination, as we’ve seen. That night, a flying saucer lands nearby, the third completed episode. And when a little alien creature comes out of the saucer, it is squirted by an oil leak from the saucer. Sam fixes the leak, and the saucer and its inhabitants take off for outer space again. The

book ends as it began—with a focus on Sam’s butt. More than a little humor animates this issue, but we also get to know Sam and Mike well enough to want to see what they’ll do next. Moore tantalizes with his characterizations rather than with specific cliffhanger episodes. As usual, Moore’s drawings are clean and perfectly executed. They seem a little sketchier than previously—the line not as liquid and flowing— but maybe that’s just Mike’s fur. In any event, I’m looking forward to the next installment—not because I’m panting in suspense because of some dire situation Moore has left Sam and Mike in but because I enjoy humor and eccentric characters. Besides—what dire circumstance bodes in the would-be buyer of the junkyard? That’s a tantalizing enough question to bring me back.

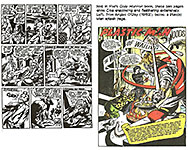

SECOND LOOKS. Returning, now, for a second look at a few funnybooks we recently reviewed here, we come upon the second issue of Moonshine by Brian Azzarello and the inestimable Eduardo Risso. Still the same masterful visual storytelling, but the story has taken a turn from realism into horror fantasy when Pirlo, the big city mobster, runs into a werewolf in the woods, eating his human prey. I’m not much of a werewolf fan, but I’ll be back again and again just to watch Risso work his wonders. In the second issue of Cage, Genndy Tartakovsky continues to tell his story in an exaggerative Kurtzmanesque manner with Luke Cage running all issue from whoever clouted him at the end of No.1. The issue ends when he encounters a facsimile of Basil Wolverton’s Lena the Hyena. We’re on the verge of looney tunes here. This issue’s advertisement for the next issue, No.3, with a cover depicting several toothsome lovelies (displayed here in Opus 359), notes about those lovelies and that cover: “This cover has nothing to do with what’s inside.” Nice. The

second issue of Shipwreck by Warren Ellis and Phil Hester perpetuates Hester’s storytelling fireworks in layout and page design as well

as chipped and clipped rendering manner. The story itself persists in being a

puzzle with Dr. Jonathan Shipwright still wandering in search of some miscreant

who may have engineered the wreck of his spaceship. The first four pages are

silent as a new character dismembers a corpse so the birds—always hovering in

this comic book—can feed. On the last pages, we are treated to an insight into

how Ellis and Hester work: Ellis’ typewritten script for an early page in the

book is followed by Hester’s pencils and inks, showing how he interpreted

and/or deviated from Ellis’ scheme for the page. From the first page to the

last, this book is a genuine treat. The second Adam Hughes issue of Betty & Veronica has arrived, and it is as delicious as the first issue in Hughes’ limning of his heroines. Betty and Ronnie continue to battle to either save or condemn to corporate obscurity Pop’s coffee shop, but it’s the pictures that we buy this book for. Although it is slowly becoming apparent that Betty is the more buxom of the pair, Hughes is persuasively subtle: he seldom draws the girls in full figure, concentrating, instead, upon their faces, which are surpassingly beautiful. He and his colorist, Jose Villarrubia, persist in dimming the lights on every page. The usual bright intensity of the artwork in a comic book is dialed back, deliberately, in order to soften the visual impact of the colored drawings. This maneuver succeeds, but it also makes the pictures harder to see; I’m not sure that’s a good idea, especially with pictures as delightful as Hughes’.

BEYOND SECOND LOOKS: Peter Hogan’s Resident Alien is about the only book I buy solely for the story. Steve Parkhouse’s drawings are okay: they’re completely serviceable for storytelling. But they aren’t of the spectacular or engaging sort I most enjoy. (It’s linework that engages me, I have finally decided; and Parkhouse’s lines are quite pedestrian. They take us for the walk but do not, in addition, impress us with their ingenuity or visual appeal.) In the third issue of the latest story arc, the alien learns that two of the town’s inhabitants can “see” through his hypnotically conveyed human appearance for public consumption and can see him as he really is. We see him, too, and we know he’s an odd-looking duck. And one of those who sees him as he is warns him that “they” (someone terrestrial or extra-terrestrial) is coming for him. The third issue of Lady Killer 2 by Joelle Jones is not awash with as much bloodshed as we usually encounter in this title: our heroine, Josephine Schuller, investigates her assistant, the “clean-up man” Irving Reinhardt, who Josephine’s mother-in-law knew in the bad old days in World War II Germany, where Irving was a monstrous doctor, conning people out of their money and then killing them. Josephine’s would-be employer—the entity that directs her assassination assignments—disengages from her when they learn of her association with Reinhardt, who, it is revealed on the last page, has just “disposed” of Josephine’s husband’s boss, an altogether nasty and objectionable man. (That doesn’t justify killing him, of course; but it’s as close to justification as this title gets.) Poor Dylan, the assassin in Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips’ Kill or Be Killed, commits another murder or two and sleeps with his roommate’s girlfriend, who likes Dylan better than Mason. But she wants “to talk” when Dylan comes home one night all banged up as a consequence of his latest encounter. The book’s scenes of New York streets at night with the snow falling are exquisite, thanks to colorist Elizabeth Breitweiser. The fifth and last (for now) issue of Kaare Kyle Andrews’ Renato Jones: The One % is out, and it is at least as fascinating an exercise in visual storytelling as the first issue—explosive episodic continuity, sudden flashbacks and wild page layouts, including a couple nearly blank spreads (for emphasis; it works). The villain is the “one percent” of the population—the really rich guys—who control everything. Renato Jones is the “freelancer” who attempts to right the world’s wrongs by killing the One%. But it’s not easy to discern his action or the plot amid Andrews’ zealous wildnesses in rampant opposition to the despised One% . He says he’ll be back with more in a second series of the title. Sex is now up to No.32, but it’s lost its appeal for me. The initiating notion, as I remember writer Joe Casey explaining it, has to do with how superheroes are, so to speak, victims of the sexual repression that accompanies being superpowered. That thread, alas, was never all that apparent, but it disappeared some issues ago, and now we have a hodge-podge of principal characters—so many, at least 19 of them, that the first page of every issue is devoted to listing and describing them because we’re likely to have forgotten them and their roles in the meandering plot—whose motives and actions are slyly alluded to each time they appear, but there’s never even a hint of resolution of the various dilemmas Casey has introduced. Wears me out just trying (unsuccessfully for the most part) to keep it all straight in my poor addled brain. As a backup story in Catwoman Election Night No.1, Mark Russell’s Prez fizzles out sadly but brilliantly. The Powers at DC have evidently decided that political satire is too risky to undertake in the Age of the Trumpet and a divided but passionate electorate (see Opus 357), so this is the last appearance of this happy frolic of a political satire funnybook. Herein, Russell takes on gun control (or, in this case, lack of it) and women’s reproductive rights, linking them for one of the niftiest wrap-ups you can imagine. The opening gun segment ends with the deaths of several open-carry advocates when the police can’t tell who the rogue shooter is. So much for the advisability of arming everyone: everyone armed is everyone a target. Later, Prez Beth is defeated in an attempt to control gun violence by limiting access to ammunition. “The Second Amendment,” she points out, “guarantees the right to bear arms, but it doesn’t say anything about ammunition. I mean, as long as we’re interpreting it exactly as it was written....,” she concludes satirically. But Russell gets in one final jab: birth control pills, which Beth’s Congress wants to outlaw, are finally permitted when they are shaped like bullets that can actually be fired from a gun rather than taken orally. Too bad there won’t be more of this caliber comedy in the future.

Quotes & Mots on Race in America “How have we come so far and yet have so far to go.”—Henry Lewis Gates, Jr. James Baldwin wrote in Harper’s magazine in 1961 that the questions that America faced about the death of segregation—a symbol of White America’s stranglehold—were “how long, how violent and how expensive the funeral is gong to be.”

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IN ORDER TO

FOCUS THIS TIME on our Xmas Shopping List (down scroll), we’re

postponing our customary review of recent editorial cartoons until next time.

But we do offer a couple of editoonery comments on the election of Donalt Rump,

gasbag blowhard and self-important sex fiend —plus an all-prose diatribe at the

end of this opus in Onward, the Spreading Punditry, our own

gasbag department. Here, we merely gaze approvingly upon the post-election

cover of The New Yorker and a pair of Trumpet portraits published in Time just after the Trump Triumph. Bob Staake’s brickwall cover for the post-election issue of The New Yorker is discussed, briefly, at the magazine’s website, where the election of the Trumpet is viewed as a major collapse of Western Civilization: “ When we first received the results of the election, we felt as though we had hit a brick wall, full force. ‘The election of Donald Trump to the Presidency is nothing less than a tragedy for the American republic, a tragedy for the Constitution, and a triumph for the forces, at home and abroad, of nativism, authoritarianism, misogyny, and racism,’ editor David Remnick wrote in a piece posted shortly after the announcement. ‘The pathos—the disappointment at waking up on Wednesday morning and not finding a woman President-elect—is undeniable, and heartbreaking,’ added staff writer Amy Davidson. Our Web site is now continually updated with reactions like these, to the news of Trump’s victory. ‘To combat authoritarianism, to call out lies, to struggle honorably and fiercely in the name of American ideals—that is what is left to do. That is all there is to do,’ Remnick concluded. And so we must go on—with words and images such as this cover by Bob Staake for next week’s issue.” I’m more than a little less alarmed about the forthcoming Trump Regime. Yes, disaster stalks at every new naming of candidates for his Cabinet. But as you’ll see Under the Spreading Punditry, there is reason for hope.

AND SPEAKING OF THE NEW YORKER, the magazine’s favorite political cover artist, Barry Blitt, enjoyed a two-page spread in the issue dated the day before Election Day. Summoning an array of past presidential candidacies, Blitt shows that many of the Trumpet’s antics were anticipated in the machinations of others who paved the way. But Blitt’s triumph extended recently beyond the pages of The New Yorker. For Vanity Fair’s Holiday Issue, he did a huge montage of political and entertainment personages summarizing events of the year from Hillary and Bill Clinton to the Zika mosquito entitled “Last Call.” In the same issue of VF, Blitt illustrated the magazine’s 2016 Hall of Fame with a drawing of Trump and Hillary. And here, just at the elbow of your eye, are these components of this month’s Blittzkrieg.

I’m not a big fan of Blitt’s work, as you doubtless have noticed. But that’s a matter of taste and has little or nothing to do with quality. And the quality of his work is not in dispute. But I love linework in cartooning and other visual arts, and Blitt’s fragile line just doesn’t strike my fancy. Sorry. I must note, however, before casting him aside again, that he is not a caricaturist: his pictures of actual people lean in the direction of illustrated reality rather than cartoony exaggeration.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS In a recent syndicated Bloomberg View column, Ramesh Ponnuru reported on a discussion between Cornel West, a rabid leftist, and Robert P. George, a outspoken conservative, on the topic of a liberal education. Said George at one point: “Our age is an age of the celebration and valorization of wealth, power, influence, status, and prestige. Those things are not bad in themselves, but they easily and all too often become the competition for leading an examined life.” The examined life, Ponnuru said, is what both George and West view as the purpose of a liberal arts education. “Its goal is to encourage critical reflection on the biggest questions; to lead us into an intellectual engagement that fulfills our nature as thinking beings; to help us achieve self-mastery; to enlarge our souls.”

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution THE PRESS AND THE PUNDIT CLASS are in a hot swivet about the Trumpet’s personal fortune and his globe girdling business empire which represents a blatant conflict of interest for the Prez-Elect. As it now stands, everything he says and does as President is likely to have repercussions affecting his wealth. The much-touted conflict, then, is embodied in a single question: how can we be sure the decisions he makes as Prez are made for the good of the U.S. and not just personal enrichment? The short answer: we can’t. Unless he sells off everything he owns, banks the money and lives off the interest. Unless he divests himself of his fortune. This solution is just a little idiotic. Americans supposedly elected a businessman because, among other things, the state of the country seemed to require businesslike administration. (We didn’t, actually, elect him Prez: by well over 2 million votes, we elected his opponent, Hillary Clinton. But we have a system for elections that is rigged—another of the checks and balances that are scattered throughout the Constitution—to prevent what the founders feared as “mob rule”; that is, the rule of the raw, illiterate and sheeplike majority in elections. So we’re stuck with the Trumpet.) Businessmen, as all of us in this capitalistic state know, are driven by a single motive—to make money, to turn a profit. Trump the businessman has already trumpeted that he expects to make a profit from his candidacy. Why not from his term of office as Prez? Of course he’ll use the Presidency to enrich himself. That’s what businessmen do. The Prez is not required by law to divest himself of his investments; the Presidency may be the only American elected office that is not encumbered by this requirement. But the populace nonetheless expects him to reduce the “appearance” of impropriety by turning his back on his business empire. Given the sprawling entangled nature of the Trumpet’s business interests, divestiture seems a terribly complex prospect. It is unlikely to be accomplished easily or quickly. Certainly not before he actually becomes Prez. We’ll be inaugurating a man with rampant conflicts of interest on January 20. And even if it were feasible to divest himself, is it reasonable to expect it? The so-called “blind trust” that many American political office-holders set up to immunize themselves from conflict of interest—letting some unknown third party run their businesses until they are no longer in office—doesn’t seem feasible either. Trump has been training his adult children to take over his business whenever he retires (or dies). To demand that he divest himself would result in divesting them, too, depriving them of their presumed inheritance. Is that fair? No. Do the mores of our nation demand that our presidents impoverish themselves before they can serve the country? Holy reason would agree: that’s both silly and impossible. And unreasonable. So for the sake of pragmatic fairness, we’re stuck with a businessman and his conflicts of interest as Prez. The plain sense solution to the problem is actually quite simple. Trump should make public all his business interests and connections so that everyone knows where conflicts of interest are possible. Then we should set up a special watch-dog bipartisan commission to keep a baleful eye on what Trump does as Prez and how it might affect his businesses. The commission can issue weekly or monthly—and certainly yearly—reports. And whenever Trump makes a presidential decision that enriches himself as a private businessman, we’ll know. And if Trump can convince us that the decisions he makes are also beneficial to the country, fine; if not, not. At least, we’ll know. And it is ignorance of conflicts of interest that most provoke us—the likelihood that some politician might enrich himself without our knowing it. We all know already that politicians get wealthier while in office. But it’d be nice to know how they accumulate all that, what favors they did to get it.

ONE OF THE FACT-CHECKING enterprises kept track of the Trumpet’s questionable utterances over the last couple years and determined that 560 of his statements were either outright lies or gross misrepresentations of the truth.

IN THIS MORNING’S PAPER, the Trumpet is quoted as saying he doesn’t need intelligence. We can tell.

IT WAS, OF COURSE, INEVITABLE. Donald Jerk Trump is Time magazine’s “Person of the Year,” that individual (group or idea), since the first one in 1927 (Charles Lindbergh), who has most influenced the events of the year, for good or ill. Not the good guy of the year; not the bad guy of the year. Gandhi made it once; so did Adolph Hitler. So did Wallis Simpson. Only a handful have made it twice. As a gauge of American influence on world events, all the doubles are U.S. presidents—FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan, George W. Bush, and Obama. Most of the second appearances are due to the Person having been re-elected to the Presidency. This year, by gaucherie alone, the Trumpet wins. Time’s attitude is indicated in the headline next to Trump’s cover photo: “President of the Divided States of America.” I don’t think we’re as divided as all that, but if the “news” media and the everlasting gasbags keep saying it, it’ll undoubtedly happen. The

best photographic portrait of the Trumpet appears on the Table of Contents

page—where he is pictured in his customary “What me? How can I explain it”

pose, smirk on his face, hands open in a gesture of complete helplessness. This annual ritual issue is out a little early this year, seems to me. I remember reading the Person of the Year issue between Christmas and New Year’s, something to do in the interregnum. Lots of reading, as usual. Some nice features—a page of “firsts” and “lasts”: the first musician to get a Nobel Prize for literature; the last day (December 31) that the Carnegie Deli will be open for business in New York. A picture of the first time Trump appeared on a Time cover—June 16, 1989, when he was celebrated as a business mogul and playboy-about-town. Famous quotes—“Grab them by the pussy.” And Joe Klein concludes the issue with a column about the Obamas. Entitled “Amazing Grace,” it talks about the Obamas as a married couple with kids who have persisted in being a married couple with kids even in the glare of the world’s most glaring spotlight. No melodrama; no scandals. “He’ll be remembered for his eulogies,” Klein notes—the things he said about the senseless deaths that occurred during his tour. “He could convey a cathartic sadness and the potential for uplift in the face of tragedy. His most perfect moment came at the funeral of the Charleston, S.C., churchgoers who had been killed by a sick white man.” The shooter had already been forgiven by the families of the dead. “How to respond to that? Words couldn’t cover it, so he sang ‘Amazing Grace’—a moment of bravado, humility and passion entwined.” Even in remembering it, my eyes tear up. We will not to see his like again.

READ AND RELISH In it’s Holiday issue, Vanity Fair listed the Obamas in its 2016 Hall of Fame, saying: “Because as they prepare to fly into the sunset, we echo the cry of Bandon de Wilde at the end of ‘Shane’: ‘Come back!’ Barack Obama’s loping elegance, grace under pressure, pinpoint humor, and jedi dedication to reason, excellence and democratic values in the face of economic collapse in 2008, a racist scavenger hunt for his birth certificate, and eight years of conservative obstruction will acquire a storybook aura for presidential historians. Featuring a First Lady whose strength, passion, and oratorical power conferred honor on us all. Admit it, America: we lucked out with the Obamas. We can only hope that, post-Obamas, our luck hasn’t run out.”

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews THE RANCID RAVES Book Grotto is littered, literally, with books we acquired with the intention of reviewing them. Alas, they’ve piled up over the years, and it has become increasingly apparent that we’ll never give most of them the kind of intensive examination they deserve. So rather than let the accretion be entirely in vain, we’ve started this new department wherein we’ll briefly describe these lost tomes by way of urging them upon you, focusing, this time, on—: