|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 328 (August 14, 2014). Down the rabbit hole this time, we critique the San Diego Comic-Con, list Eisner Award winners, look at comic strips that celebrated the Sandy Eggo Con, contemplate some antique magazine cartoons, laud the Death of Archie, and contemplate a documentary on Gahan Wilson, and, as usual, we review some of the best editorial cartoons of the month. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

Error Up Front SAN DIEGO COMIC-CON 2014 Police State Personal Adventures, Previews & Reviews Sandy Eggo Sues Salt Lake Comic-Con San Diego Convention Center Sued

NOUS R US Eisner Award Winners Odds & Addenda: Stan Lee No Show; Parade Cartoon Boolet, Scholastic Bone

EDITOONERY Congress Delinquent, Gaza Aflame Gospel According to Political Correctness Washington Redskins

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Sandy Eggo in the Funnies

BOOK MARQUEE Gahan Wilson: Born Dead, Still Weird (a documentary)

BOOK REVIEWS Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year: 2014 Edition

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Gahan Wilson in 1956 Mae West in Ballyhoo Julian Dedman before Playboy Rea Irvin in New Yorker New Yorker Covers

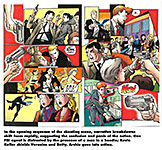

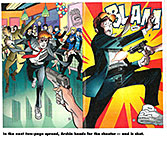

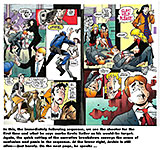

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE The Death of Archie: Superbly Done Hawkeye No.19 Harley Quinn Invades Sandy Eggo Groo vs. Conan Outcast

PASSIN’ THROUGH Jay Maeder

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

ERRORS UP FRONT. When we make mistakes here at Rancid Raves, we post corrections as soon as we uncover them—and we post them up front, first. So here we go for the most recent catastrophe: Erroneously through the mechanism of a brain fart, I called Pat Bagley Pat Brady in discussing a cartoon by the former in Opus 327. I know them both; my apologies to each.

INTERNATIONAL COMIC-CON SAN DIEGO And Its Discontents IF THERE IS AN APPROPRIATE WORD for the San Diego Comic-Con it must be found among the synonyms for excess: extravagant, intemperate, immoderate, swollen, bloated, prodigality, incontinent, exorbitant, nimiety, excrescent, superabundant, and, at last—at long last— crapulous. Not that there is an overabundance of popular culture artifact at the Con. Not at all. There is much more popular culture artifact beyond the walls and halls of the San Diego Convention Center (itself a monument to giantism). What there is a surfeit of in the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con is fuss about popular culture artifacts—movies, tv shows, science fiction, games, toys, superheroes, costumes. The fuss is what’s excessive. Alas, though, comic books, the foundational artifact, are not much in evidence. Superheroes, yes; costumes, yes. But relatively few of the four-color phenomenon itself. But there is also exuberance. On the first day, I am always almost overcome with delight: how wonderful! I hope this goes on forever! By the last day, I am weary of the fuss: is this going to last forever? Will it ever end? For about 130,000 attendees every recent year, it never ends. It is now a firmly established perennial. And the Con has scaled the heights of popular culture: it’s mentioned in national newscasts, and every year, Entertainment Weekly, the ultimate arbiter in popular culture pronouncements, previews the Con the week before it begins, and after it’s over, EW tells us what went on. But only in movies and tv. The rest—games, toys, comics—is entirely ignored. EW’s coverage this year ran to 15 pages. Billed as a “complete recap,” it’s all just photos of movie stars. Two pages are devoted to the “Confessions of a Comic-Con Virgin,” Daniel “Harry Potter” Radcliffe, who recounts his impressions of his first comics convention. Mostly, he talks about other movie stars he either met or hoped to meet. He does, however, make one remark about comic books: “I was a huge comic book fan growing up,” he says, “—Spider-Man, Daredevil, and the Flash. But I really must catch up on television.” That’s it. Like everyone else, he wants to catch up on tv. And that’s why the big mob shows up every year—to catch up on tv. And movies. All the latest self-proclaimed blockbusters. In his newsarama.com wrap-up on the Con—“What’s Right and What’s Wrong about the San Diego Comic-Con”—Jim McLauchlin points out that the Sandy Eggo officials are fully conscious of the criticism that the Comic-Con is no longer much about comics. Or is it? Says McLauchlin: “A few years ago, when the fanboys lit their torches and sharpened their pitchforks screaming ‘you sold out!’ the Con trumpeted that they still had more hours dedicated to straight comics programming, more hardcore comics events, and more comic book vendors than any other damn show in the country. And they were absolutely right. In this, San Diego sits in position of paradox: They have more comics than anyone, yet comics are somehow subsumed, pushed to the side.” Not only are comics subsumed: the whole Con is but the tentpole of the San Diego experience during Comic-Con Week. The Con’s concentration of popular culture itself has moved out of the Convention Center and into adjacent hotels and the surrounding environs. Streets in the nearby Gaslamp Quarter are closed to automotive traffic to make room for teeming throngs of pedestrians stalking a good time. Here’s McLauchlin’s picturesque report on this new phenomena: “Tendrils snake throughout the city, as parties happen throughout the Gaslamp Quarter, and even Stone Brewing five miles away. I spoke to one of the floor managers for Comic-Con, and he said they had identified a staggering 93 events happening in San Diego over the weekend that rode the coattails of the massive wave of humanity descending toward the marina [next to which the Convention Center sprawls]. A perfect example is the Samsung Galaxy Experience, which popped up at Petco Park. For the low, low price of ‘free’ (and getting marketed at) people could swing by the Samsung lounge and enjoy free drinks. ‘I hung around for hours, had a bottle-and-a-half of red wine and got good and stewed,’ one woman said. ‘Best deal at the con.’” McLauchlin continues: “San Diego at con time is now rife with outside events, many free. It allows more people to ‘have the experience,’ a necessary shift, as the con is now at a point where they have an active interest in driving people out of the Convention Center.” The more people that can be lured away from the gigantic structure, the happier the city’s fire marshal is. And the Con is actively working to reduce some portions of the crowd (to make room for more paying customers). “Last year,” McLauchlin goes on, “the Con did away with a second complimentary admission for Artist Alley table holders—the Alley crowd now must go it alone. Press credentials were severely curtailed this year. And next year, the Con will reduce complimentary professional badges by 30%.” But that may not matter. Comics professionals, according to McLauchlin, are showing less and less enthusiasm for the event. Every year a few months before Sandy Eggo, McLauchlin mails to about 500-600 comics creators he knows, asking if they’re going to be there. “Over the last four years,” he reports, “I’ve seen many of the ‘no’ answers move from a simple ‘no’ to ‘Hell, no’ to ‘f**k no!’ to ‘I’m never going to that damn place again in my life.’ My perception, which has been reinforced literally hundreds of times, is that the Con has simply become something that many creators—arguably, the most important footfalls that could potentially waltz through the door—don’t want it to be. Many cite the crowds. Some cite the madness. Many point to the Hollywood-ification of San Diego, and their perception that the Con just doesn’t give a crap about them anymore. “If that’s true, make no mistake—many creators just don’t care about San Diego, either. They’re happy to stay at home and avoid the crowds, madness, and Hollywood-ification. The thing is, you as a fan/consumer don’t know who’s not there. Because it’s very hard to figure out who is there.”

AND THERE ARE OTHER UNHEALTHY SIGNS AND PORTENTS about the Con. Beneath all of the ebb and flow of the mass of humanity filling the aisles and hallways eddies a vaguely sinister undertow. The San Diego Comic-Con may be the closest thing our culture has produced to a benign police state. A mob of 130,000 people, however happily disposed, needs to be managed, controlled. The overweening evidence of control is The Line. There are lines for everything. Everyone is in line. For food, for drink, for program sessions. Throughout the upper floors of the Convention Center where all the meeting rooms are, volunteers wearing t-shirts emblazoned “Line Staff” steer the lines to and from meeting rooms. Some of the upper floor hallways are designated “entrances”: you get to a meeting room by “entering” through the “entrance” hallway. You leave by way of the “exit” hallways. And security staff, ubiquitous and numerous, stands guard to make sure that you obey—entering only through entrance hallways; exiting only through exit hallways. In the quarter-mile long lobby on the ground floor, signs overhead designate “entrances” and “exits” where there are neither: an “entrance” in this vicinity is merely that part of the lobby where the crowd goes in one direction; “exit” designates that part of the lobby where the flow is in the opposite direction. The signs indicate the direction of the traffic, not where you can enter or exit. And the doorways of the Center are similarly designated “entrance” and “exit.” Often, the one is immediately next to the other. And if you try to leave the building through a doorway designated “entrance,” a security guard will stop you and direct you to the “exit” doorway—which is usually just six feet to the left of the “entrance” doorway. Through most of the day, there aren’t enough people going in or going out to create any sort of traffic jam at either exit or entrance. But the rule holds: enter through the entrance doorway; exit through the exit doorway. One morning, after a leisurely breakfast at a waterfront restaurant near the Convention Center, I decided to enter the building from the bayside rather than the streetside. The Center opened at 9:30am, and it was now 9:50am, so I anticipated no problem getting in. Wrong. When I came to the massive stairway that leads from water’s edge to the Center’s entrances, barricades were up, preventing access. And a security guard said I couldn’t enter by way of the stairs until 10am, five minutes away. Why? I asked. “Line management,” he said. But realizing that was too cryptic, he explained that sometimes the line awaiting the opening hour stretches all along the streetside front of the building, around the corner, and on to the bayside of the building. I recognized that managing that quantity of people and length of line was a challenge, but on this particular morning, the only people in view were me, the guard and three other would-be attendees. No crowd. No line. But “line management” prevailed nonetheless. Upstairs on the floors of meeting rooms, line management is a way of life. Hours before some events, people begin lining up to enter meeting rooms where big-time movie stars will hold forth. The lines form along the wall of the hallway, and when the line grows too long for the hallway, it is broken and continued in another hallway—or outside on the patio. When the meeting room at last opens, Line Staff guides the line from outside into the building and across and down the hallways to the meeting room—holding aloft on sticks signs that stop traffic to permit the line to pass by in one continuous flow. But standing in line is no guarantee that you’ll get into the meeting room you’re waiting to enter. Audiences are not required to leave a room after the presentation they’ve just witnessed; and if enough of them stay in their seats for the next session, many of those in line will not get into the room. It’s a gamble, McLauchlin says: “You’ll lose just as often as you win, and waste a hell of a lot of time in the process. It’s like blackjack without the free drinks.” Perhaps the most insidious evidence of the police state are the signs on the walls of all lobby areas that announce: “No sitting or standing by order of the fire marshal.” Line management, in other words, is partly to control the flow of the multitudinous horde. But it is also to make possible a quick exit from the building in the event of fire. People sitting on the floor in the lobby—there is no place else to sit, no chairs—would be an obstruction to a no longer ruly mob fleeing a fire. And people would be trampled in the fleeing melee. So no sitting is allowed. Standing is likewise a potential obstruction, so no standing is permitted. Security guards stand throughout the lobby at intervals of about 10-15 feet (or so it seems) to make sure no one else is standing. No kidding. One afternoon, as I was passing through the lobby, I heard my name shouted, and turned to see an old friend. We stopped to chat. Almost immediately, a security guard came up to us and told us we couldn’t stand there.

Few mind—or even notice—that they are living in a police state during the Sandy Eggo Con. Here the antique Roman axiom about bread and circuses seems eminently applicable. The poet/playwright Juvenal coined the expression as a metonymic for a superficial way of keeping the populace docile. If the common folk are supplied with sufficient bread (sustenance) and circuses (entertainments), they’ll have no reason to object to or interfere with the machinations of the rich and powerful, who may, then, exploit the populace to a fare-thee-well. Those who attend the Comic-Con have sufficient bread (wealth, in this case—enough to afford to buy one of those expensive admission tickets) to enjoy the circus (the festival of so-called popular culture that transpires annually in San Diego), and so, supplied with bread and circuses, they don’t notice that they are being controlled by an incipient police state. I, on the other hand—being sheerly perceptive—notice that I’m in a police state, but, apart from expressing occasional annoyance at being “line managed,” I don’t mind much. I’m too busy having a good time—oogling the displays (both of artifacts and epidermises), costumes and other antics, products and toys, and drawings, both comic and illustrational.

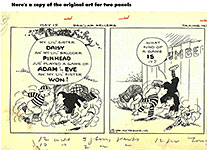

I DIDN’T SHOP MUCH FOR FUNNYBOOKS. I brought my Want List this year, but didn’t take it out. I bought only four comics—all Plastic Man of the Silver Age, all drawn by Ramona Fradon, to whom I’ve often said: “You drew the best Plastic Man since Jack Cole. To which she usually responds: “Yes, I know.” I also picked up a copy of (the late) Doug Wildey’s Rio: The Complete Saga, a fresh 2014 reprinting of all the Rio westerns, including “two never-before released graphic novellas.” Apart from enjoying the stories and Wildey’s artistry, I was fascinated by the final tale. Never completed, it offers many pages of final art but several pages in various stages of incompleteness. Some panels are inked; some, still just penciled. And speech balloons, likewise just penciled in. We cn see Wildey’s thought processes as he tinkers with wording and picture composition. I bought three original Reg’lar Fellas comic strips by Gene Byrnes. I try to resist buying original art (mostly because I’m a sucker for buying more than I can possibly display on whatever walls are left unfestooned at home), but in this case, I couldn’t restrain myself. The price was good, and I’ve admired Byrnes’ ever since studying cartooning in his 1950 book, A Complete Guide to Professional Cartooning. So when I saw a heap of his strips among piles of old comic books, I went for three. I tried for two, knowing I wouldn’t be content with only one. But in negotiating the price, I managed to reduce it enough that I could afford three (of which, two are on display here). I chose strips displaying Byrnes’ typically energetic rendering of youthful life—kids forever in motion, running, jumping, swinging. I also wanted pictures of Bullseye, the dog that follows the kids around. The strips I settled on include Bullseye and the chief characters—Jimmy Dugan (whose little brother Dinky shows up in later years), Puddinhead Duffy and his kid brother Pinhead. Dunno who the bare-headed blond kid in overalls is.

The strip started under another name in 1916 or so and became Reg’lar Fellers later in the run, which lasted until January 1949. George Carlson (of Jingle Jangle Tales fame) drew the strip for a time (in the 1930s I think); my onsite expert spotter is sure all these are by Byrnes himself. I dropped by the Uclick booth where Lalo Alcaraz was signing prints of one of his Sunday La Cucaracha strips and copies of a new graphic history book he illustrated for Ilan Stavans, A Most Imperfect Union: A Contrarian History of the United States. (As George Washington dies, he orders that all his slaves be freed upon the death of his wife Martha, but an onlooker mutters, “My stars! He sounds delirious. Better keep slavery going for a while.” As it happens the authors tell us, Martha freed her slaves eighteen months before she died.) In 2000, Alcaraz and Stavans produced another graphic history, Latino USA, revised in 2012. Imperfect Union is essentially a verbal history, a collection of historical facts, upon which Alcaraz’s pictures often comment ironically. There is little pictorial narrative in the comic strip or comic book manner. I also bought a copy of UG!3K, 160 pages of reprints of selected underground comix shorts. Several well-known ug cartooners are represented (R Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Gilbert Hernandez, Larry Todd, Larry Welz, Guy Colwell) but many herein have long fled the underground scene, whatever remains of it, and are no longer readily recognizable. I neglected this year to tour the small press area although I stopped to chat with Keith Knight (and brought his latest, Knight Takes a Queen, the second collection of his syndicated comic strip, Knight Life) and Stan Yan, the Denver cartoonist presently specializing in zombie caricatures (see Opus 327). At a booth operated for the publisher McFarland, I bought a copy of The Meaning of Superhero Comic Books by Terrence R. Wandtke, a professor of literature and media studies at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois. McFarland has an extensive list of books on comics and other aspects of popular culture, but most of the authors of the comics-related tomes, like Wandtke, are unknown to me. But his thesis sounded intriguing (if a little hackneyed): he supposedly explores the relationship between the superhero story and ancient folktales, revealing a connection between traditional aesthetics and postmodern theories. I suspect he, like many of the academic persuasion, is belaboring the obvious, so I bought the book just to see if my suspicions are correct. Perverse, I realize; but that’s the name of the game here at Rancid Raves. At TwoMorrows, I picked up a copy of Jon B. Cooke’s Comic Book Creator, No.9, which features “the comix book life of Denis Kitchen.” I plan to review that in connection with another Kitchen tome, The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen, which has been sitting on the “review” shelf too long. And

I stopped by Curio & Company to buy a copy of their latest hoax, Spaceman

Jax, a spoof of a certain type of 1950s comic book genre. Kirstie

Shepherd and Cesar Asaro, who usually reside in Vienna (she’s a

California native; he’s Italian), became celebrated here in Rancid Raves for

manufacturing a faux comic strip, Frank and Friend, that purported to be

a long-lost cartooning artifact but is actually a completely fraudulent

concoction—so artfully and thoroughly achieved as to be jaw-droppingly

entertaining. Ditto Spaceman Jax. (Frank, by the way, is the rag doll in

the accompanying illustration.) Beware: everything on the website is faked historical artifact. It’s all make-believe even though you can buy the books (perhaps not the soft drink that Spaceman Jax promotes) and the comic book. But the $1.25 price that appears on the cover of the paperback is part of the hoax: it apes the look of 1950s paperback books. In this case, the actual price of the book is $11.95 And before I left the Comic-Con premises, cartoonist Phil Yeh thrust into my hands the latest issue of his magazine, Uncle Jam (No.104), which includes a 2013 interview with Alex Nino and a history of Michael Gross, among sundry other articles on lovingly offbeat topics. The magazine is free; you can find it online at Yeh’s wingedtiger.com, where you can read it without charge. Despite

all my carping, the Con is fun. I’ve been coming back for more than twenty

years, and I realize the necessity for line management in a swarming mob of

Comic-Con’s dimensions. “It is a thermodynamic freakin’ miracle that 99% of the convention runs smoothly, efficiently. ... In this, the convention organizers are to be lauded. Hell, if you’re behind the curtain at the 2nd grade Spring Fling music recital with kids dressed as flowers and ladybugs, things can get damn chaotic. Multiply that flower to the power of Tom Hiddleston in a Loki suit and make those ladybugs 15,000 people trying to get into Hall H, and the chaos becomes biblical in proportion. The fact that the madness behind the curtain stays there, and 99% of people are having a good time at any given time is a blessed event. “This point cannot and should not be understated: the convention organizers are to be lauded for making the vast majority of things work out. One analysis of the Con could certainly reveal (should you choose to look at it that way) that since so much runs so well over the course of so many days, any faultfinding with San Diego is nitpicky at best. It’s crumbs fallen off the table at an Olympian feast. ... There were 873 things happening simultaneously, and you chose to stand in a line for one, while the other 872 were a straight party. That’s on you, son. It was a smarter (and better-paid) man than me who said ‘You can’t please all of the people all of the time.’” And this may be a good time to remember that it was chiefly Shel Dorf who set the table for that Olympian feast. In his last years, he was not deliriously happy that Hollywood occupied such large acreage of the Con’s landscape, but he had invited them. He wished the present organizers hadn’t let cartoonists slip out of their grasp in the eagerness to embrace movies and television. But motion picture entertainment had always been part of his interest and enthusiasm. He conceived of a convention that would feature movies and sf as well as comics. And at the first Comic-Con over four decades ago, George Lucas showed slides of a movie he planned to make about star wars.

SANDY SUES SALTY WHILE IN THE GRIP of the passion to control everything, the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con officials have issued a cease-and-desist order to the organizers of the Salt Lake City Comic Con, demanding that they drop “Comic Con” from the name of their shindig. The California contention is that the Utahns’ use of the term breeds “confusion” among the populace, who, seeing “Salt Lake City Comic Con,” think erroneously that “your convention is in some way affiliated with the San Diego convention.” And we certainly can’t have that. Or can we? Ironically for the Sandy folks, the confusion was long ago reduced to a simple formula. As Jim McLauchlin declaimed in his newsarma.com critique of the San Diego Con: “Comic book conventions can be roughly sorted into two categories: San Diego and ‘all others.’” Among the others are dozens of cons that deploy the allegedly hijacked term: Baltimore Comic-Con Central Coast Comic Con Rose City Comic Con New York Comic Con Lethbridge Comic Con Santa Fe Comic Con Ohio Comic Con Rhode Island Comic Con Brasil Comic Con And this muster scarcely exhausts the list. Is Sandy Eggo going to sue them all? Not likely. The

trouble began, reports Sean P. Means at the Salt Lake Tribune (one of

the organizing entities behind the Salt Lake Comic Con), when Salty

representatives took a customized (“skinned”) audi to San Diego during the

extravaganza there and drove it around the neighborhood with “Salt Lake Comic

Con” emblazoned on its sides. In the promotion game, driving the decorated auto around Sandy Eggo’s site was not intended to cause confusion as much as it hoped to catapult from one comic-con an equivalent enthusiasm for another, a not unreasonable expectation what with all the other comic-cons doing exactly the same thing from sea to shining sea. Deploying the term “comic con” (hyphenated or not) evokes thoughts of the Sandy Eggo extravaganza and trumpets to a watchful public: “Look! We have one of those here!” The San Diego Comic-Con has several registered trademarks that include the hyphenated “Comic-Con,” but like many trademarked names—trampoline and raisin brand among them, and shredded wheat, aspirin and zipper, not to mention the notorious kleenex—“comic-con,” with or without the hyphen, has become genericized. So successful has the original comic-con at San Diego become that its once unique descriptor now applies to any and, indeed, all such convocations as the San Diego geekfest. In fact, “con” has supplanted “convention” as the name of a convening on any subject—literary con, scifi con, porno movie con, garden con, floral display con, and so on into the night. Sandy Eggo was, for years, the largest comic-con in the country. Lately, that status is being challenged. The first Salt Lake City Comic Con last year drew over 70,000 attendees. Smitten with success, the organizers mounted a spring fling dubbed FanXperience, which registered 100,000 people, putting it in the same league as San Diego and its New York City competitor, which ranks second. The next Salt Lake Comic Con is schedule for Sept 4-6. Although brought to a head by the car caper in San Diego, trouble had been brewing for months. According to Bryan Brandenberg, Salt Lake’s co-founder and chief marketing officer, Sandy Eggo was initially upset that the Salt Lake team scheduled FanX the same weekend as the San Diego organizers’ other event, WonderCon, in Anaheim, California. Brandenberg claims the FanX date was chosen because that was when the city’s convention center was available. Moreover, at the time that they set the date, WonderCon had not confirmed when it was happening. Who might win if the trademark issue goes to court? Means asked Amelia Rinehart, a professor at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney School of Law — and an expert on intellectual-property issues — how she would argue each side of the case. The Sandy side: "If I represented San Diego Comic-Con, I have several federal [trademark] registrations. Some of them are incontestable. … That means that I have very strong rights that are national in nature for things that associated with my mark: entertainment services, comic-book conventions, that sort of thing. … To the extent that other comic-book conventions are using the mark in a way that’s likely to confuse consumers about the origin of their services, I can shut them down if I want to. Or try to, anyway." The Salty side: "A strong argument would be that I am merely describing what I’m doing. It’s a comic-book convention, and ‘comic con’ is descriptive of that, and I’m using the term fairly just to describe what I’m doing. I think an alternative argument — if I was trying to get the mark canceled, which would eliminate all the rights for San Diego — would be that it’s generic for comic-book conventions. People just use that term as the thing itself. There’s no signaling of source by the term. It’s just a description of what’s going on, and generic for that thing." The Sandy Eggo legal team would be fine with Salty using FanXperience for their event—or expanding their name to Salt Lake Comic Convention. It’s just “comic con” that gets their wattles in an uproar. But, Brandenberg told Michael McFall at the Salt Lake Tribune, submitting to the cease-and-desist order would threaten "all other comic cons by trying to prohibit them from using the term." Brandenburg pointed out that San Diego Comic-Con tried and failed to trademark "comic con" in 1995 [despite the clear and documented claim of the lawyer’s letter; maybe they were successful in trademarking the term in a later application]. "Furthermore, precedence for the mark ‘comic con’ was set when Denver Comic Con received [in November] a trademark for their convention. Nobody owns the words ‘comic con’… and the United States Patent and Trademark Office has already ruled on this.” But whatever happens in the legal sphere, Means went on, “Salt Lake Comic Con has already won in the court of public opinion. San Diego’s cease-and-desist letter allowed Salt Lake Comic Con’s folks to portray themselves as David being picked on by Goliath. They did so quite expertly, as the story spread to thousands of news websites around the world — and sparked Internet memes analogizing the two comic cons using all manner of geek iconry. (My favorite was the ‘Game of Thrones’ meme, with San Diego Comic Con as the bratty King Joffrey and Salt Lake Comic Con as the small but sharp Tyrion Lannister.) “The old saying goes,” Means concluded, “that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. So far, Salt Lake Comic Con has played its hand well and continues to reap the winnings.

More Legal Machinations in San Diego MEANWHILE, THE VERY FUTURE of the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con is threatened by legal actions pending in the courts. Plans to expand the Convention Center—an expansion that convinced the Sandy Eggo organizers to keep the Comic-Con in the city—have run up against a couple of hurdles. One lawsuit alleges that the $525 million expansion does not comply with the California Coastal Act and is therefore “illegal.” A second suit contends that the city’s funding plans are illegal and that the initial projections of cost were wildly underestimated. A representative of the group saying the funding is illegal says the expansion project is now “five years away from breaking ground at the earliest because the city has botched the financial projections.” But even if this estimate is wrong—if it won’t be five years before construction begins—the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con is in a precarious situation. Several years ago at about the time Sandy Eggo’s long-term contract with the city’s convention was up for renewal, the Con’s organizers started looking around for another home. The city’s fire marshal had capped the Con’s attendance at 125,000, frustrating thousands of fans. And the Con had more applications for exhibit booths than the convention center had space. In short, before any further growth could take place, the Con needed a larger venue. They looked at Los Angeles and Anaheim. But since the Comic-Con is the largest convention hosted in San Diego, the city and the hotel community mounted an enthusiastic bid to keep Sandy Eggo in the city. Among the inducements—an expanded convention center that would hold more exhibits and have room for more attendees. Sandy officials agreed to renew their contract through 2016 in the expectation that the expansion would be in place by then. Doesn’t look like that will happen. Not in time. And now might be a good time for Sandy Eggo organizers to threaten to pull out again. Looking at the astronomical hotel room rates that Comic-Con attendees have to pay, I think the organizers could hold out for larger discounts. The discounts probably run in the neighborhood of 30 percent these days. If the hotels value the business, they could increase the discount to 50 percent. (Which is what the Sandy Eggo officials should have demanded in their previous negotiation. And I’m not just blowing discontented smoke: I was a convention manager for thirty years and negotiating room rates with hotels was one of the things I did. A 30 percent discount for a convention like the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con is shamefully low.) Now’s a good time to make a move: the success of the Con and therefore its economic value to the city gives it clout when it comes to negotiating room rates and such matters. And the iffy status of the crucial Convention Center expansion provides the excuse to enter into negotiations again. And time is not on Sandy Eggo’s side. For the past several years, the Con has been riding the wave of Hollywood success with blockbuster movies about comicbook superheroes. How long will that fad last? And when the steam escapes the superhero blockbuster, the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con can expect to experience a ripple effect in the shape of a minor tsunami that will sweep away both attendance and celebrity visibility at the Con, the latter at present a huge magnet for attendees. In Hollywood, movie makers have expressed trepidation about the future of comicbook superhero movies. In the midst of a plethora, they wonder how long it will continue. And what should happen next. This summer, we have the first evidence of the movie moguls’ uneasiness. “Guardians of the Galaxy” is about comicbook superheroes, but these guys are below the horizon in Marvel’s universe—so far below that, except for the attention of a few of the more fevered fanboys, the Guardians might never have appeared in comic books: they could well have been originated expressly for the movie. It would seem, then, that Hollywood’s plan for the day when comicbook-inspired movies fade away is to come up with new superheroes, concocted just for the movies. “Guardians” did well at the box office: $94 million on its opening weekend, setting a new record for August movies. And that bodes well for the next phase of blockbuster movie-making. But the Sandy Eggo Comic-Con’s future is still not guaranteed. In short, Salt Lake City’s comic-con is the least of the troubles lurking just beyond the horizon for Sandy Eggo.

QUIPS & MOTS In the aftermath of the Comic-Con, we remember our hotel experiences. “What a hotel! The towels were so fluffy I could hardly close my suitcase.”—Henny Youngman “Here’s a little tip from me to you as an experienced traveler. Wake-up calls are the worst way to wake up. The phone rings. It’s loud. You can’t turn it down. I avoid this horror by leaving the number of the room next to me, and when the wake up call comes, it just rings kind of quiet, and you hear a guy yell, ‘What are you calling me for?’ Then you get up and take a shower. It’s great.”—Garry Shandling “Hotels are notorious for being noisy when they’re occupied by conventions. During the Sandy Eggo Con, one time in the middle of the night, I was awakened out of a sound sleep by a woman screaming. Screaming and pounding on the door. I rolled over and tried to get back to sleep, but it was no good: the woman’s screams penetrated every ear drum at my disposal. I just couldn’t stand it, so finally I got up and let her out.”—RCH

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Eisner Winners, 2014 Announced at the San Diego Comic-Con on Friday night, July 25—: Best Short Story—“Untitled,” by Gilbert Hernandez, in Love and Rockets: New Stories No.6 (Fantagraphics) Best Single Issue (or One-Shot)— Hawkeye No.11: “Pizza Is My Business,” by Matt Fraction and David Aja (Marvel) (PIZZA DOG!!!) Best Continuing Series— Saga, by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples (Image) Best Limited Series— The Wake, by Scott Snyder and Sean Murphy (Vertigo/DC) Best New Series— Sex Criminals, by Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky (Image) Best Publication for Early Readers (up to age 7)— Itty Bitty Hellboy, by Art Baltazar and Franco (Dark Horse) Best Publication for Kids (ages 8-12)— The Adventures of Superhero Girl, by Faith Erin Hicks (Dark Horse) Best Publication for Teens (ages 13-17)— Battling Boy, by Paul Pope (First Second) Best Humor Publication— Vader’s Little Princess, by Jeffrey Brown (Chronicle) Best Anthology— Dark Horse Presents, edited by Mike Richardson (Dark Horse) Best Digital/Webcomic— The Oatmeal by Matthew Inman, theoatmeal.com Best Reality-Based Work— The Fifth Beatle: The Brian Epstein Story, by Vivek J. Tiwary, Andrew C. Robinson, and Kyle Baker (M Press/Dark Horse) Best Graphic Album (New)— The Property, by Rutu Modan (Drawn & Quarterly) Best Adaptation from Another Medium— Richard Stark’s Parker: Slayground, by Donald Westlake, adapted by Darwyn Cooke (IDW) Best Graphic Album (Reprint)— RASL, by Jeff Smith (Cartoon Books) Best Archival Collection/Project (Strips)— Tarzan: The Complete Russ Manning Newspaper Strips, vol. 1, edited by Dean Mullaney (LOAC/IDW) Best Archival Collection/Project (Comic Books)— Will Eisner’s The Spirit Artist’s Edition, edited by Scott Dunbier (IDW) Best U.S. Edition of International Material— Goddam This War! by Jacques Tardi and Jean-Pierre Verney (Fantagraphics) Best U.S. Edition of International Material (Asia)— The Mysterious Underground Men, by Osamu Tezuka (PictureBox) Best Writer— Brian K. Vaughan, Saga (Image) Best Writer/Artist— Jaime Hernandez, Love and Rockets New Stories No.6 (Fantagraphics) Best Penciller/Inker or Penciller/Inker Team— Sean Murphy, The Wake (DC/Vertigo) Best Painter/Multimedia Artist (interior art)— Fiona Staples, Saga (Image) Best Cover Artist— David Aja, Hawkeye (Marvel) Best Coloring— Jordie Bellaire, The Manhattan Projects, Nowhere Men, Pretty Deadly, Zero (Image); The Massive (Dark Horse); Tom Strong (DC); X-Files Season 10 (IDW); Captain Marvel, Journey into Mystery (Marvel); Numbercruncher (Titan); Quantum and Woody (Valiant) Best Lettering— Darwyn Cooke, Richard Stark’s Parker: Slayground (IDW) Best Comics-Related Periodical/Journalism— Comic Book Resources, produced by Jonah Weiland, www.comicbookresources.com Best Comics-Related Book— Genius, Illustrated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth, by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell (LOAC/IDW) Best Scholarly/Academic Work— Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation, edited by Sheena C. Howard and Ronald L. Jackson II (Bloomsbury) Best Publication Design— Genius, Illustrated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth, designed by Dean Mullaney (LOAC/IDW)

ODDS & ADDENDA Stan Lee

didn’t make it to San Diego for the Con. He was attacked by laryngitis, and at

91, that was enough for him to count himself out. And I agree: a silent Stan is

no Stan at all. ... Betty White was rumored to be scheduled for an

appearance, too; but she wasn’t there. ... The Sunday newspaper supplement

magazine Parade has now published on successive weeks two more four-page

booklets of seven cartoons each, replacing the magazine’s traditional interior

feature, Cartoon Parade. From a press release: To kick off the celebration of the 10th anniversary of its Graphix imprint, Scholastic will release a special edition of Jeff Smith’s Bone Vol.1: Out From Boneville. Established in 2005, Graphix, Scholastic’s graphic novel imprint, launched with the colorized version of Smith’s Bone, effectively establishing the work as the cornerstone of the imprint. Out February 2015, the new special edition will be in full color and will include an illustrated poem by Smith plus original Bone tribute art (mini-comics and splash pages) from 16 other artists, including Kate Beaton, Jeffrey Brown, Kazu Kibuishi, Dav Pilkey, Raina Telgemeier, and Craig Thompson.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS Art Spiegelman said he liked comics being lowbrow and disreputable but he has become one of the people who made comics respectable. Asked about this by Molly Crabapple, Spiegelman responded: “It’s a Faustian deal. I was attracted to comics because they were outside the culture in a weird way. There wasn’t a canon, and that meant that it was all open for me to explore my own continent, which was useful for somebody who was only partially socialized. “If you were in college and you were my age, you’d read Marshall McLuhan. He was saying when a medium stops being a mass medium, it either dies or becomes art. Comics were on that path. “It wasn’t the comics in 1900. It wasn’t like the comic book in 1940. All those idioms, including the newspaper strip, were withering away. It seemed like we needed to have a new deal in the world because if we wanted to get grants like poets got, we had to be considered as valuable to the culture as poets were. So this meant the Faustian Deal. You consciously try to make a liaison. Not just with the head shops, but also with the bookstores, libraries, museums and universities. That way, one can build a support system. If you have a support system, the medium stays alive.”

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution From The Week, quoting and paraphrasing Dan Milbank in the Washington Post: “Today, everything connected to politics is theater, and the national debate has become a series of one-act plays, each running for only a week or two. Two weeks ago, the show was about IRS official Lois Lerner’s missing e-mails, and before that, it was ISIS’s advance in Iraq, and before that, the Bowe Bergdahl prisoner swap. Remember the kidnapped schoolgirls in Nigeria? Or the Veterans Administration scandal? Or the missing Malaysian plane? All of these stories were interesting enough, but America has a serious ‘attention-deficit problem’ and we moved on. We swing from crisis to crisis, problem to problem, never pausing long enough to bother resolving any of them. The sound and the fury are what matters. Once the entertainment value of a story wanes, everyone loses interest. What will be next week’s episode of political theater? The show must move on.”

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE NEWSSHOW FOR THE LAST SEVERAL WEEKS has focused our attention on two events over all others: the infantile irresponsibility of the Congress, adjourning for a five-week vacation without attending to pressing business, and the Israeli-Hamas War in Palestine. The editoonist’s chief weapon is the imagery of his cartoon and the visual metaphors he may construct to make his/her point. At

the upper left in our first visual aid, Pat Bagley deploys an image that

numerous of his colleagues used—a fat and lazy Congress contemplating a

fun-laden vacation but ignoring the urgent needs at hand. And well should the mob clamor: the 113th Congress takes time off having established itself as the most do-nothing Congress in modern times. And on the penultimate day in session, Speaker John Boehner (pronounced “blather”) pulled two bills off the floor because he knew the pachydermous Tea Baggers wouldn’t vote for them; these bills would have taken steps to house and process and deport thousands of unaccompanied minors from Central America who had crossed our borders illegally in recent months. At the last minute, Congress approved more money for the VA and for highway construction, but that scarcely erases its record for doing nothing. Ironies abound. Boehner is suing Bronco Bama for taking executive actions without the support of Congress, but after pulling the two bills that he asserted would solve the problems at the border, Boehner changed his tune and went in the opposite direction: “There are numerous steps the President can and should be taking right now, without the need for Congressional action, to secure our borders and assure these children are returned swiftly and safely to their countries.” Congress also left without passing the 13 funding bills that must be approved by the end of September to avoid another government shutdown. This kind of behavior is doubtless the inspiration for Rick McKee’s cartoon, next on the clock, which offers a telling image of Congress as an ostrich, sticking its head in the sand and ignoring its surroundings. Daryl Cagle, recognizing that the problem with Congress is that the Republicons, divided into two factions by the obstreperous Tea Baggers, cannot act, gives us an image of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm so tied up in the knots of his own appendages that the GOP is rendered immobile. Bill Day’s image, next in clockwise rotation, uses a modification of a common street sign often found along streets next to playgrounds; the image emphasizes the juvenile irresponsibility of the Congress, suggesting that Congress is merely “playing” rather than actually governing. Then at the lower left, Mike Keefe combines two of the most urgent issues that the vacationing Congress ignores—failure to fund highway construction and immigration reform—with a memorable image, the accompanying verbal content giving potent meaning to the imagery. The

war in the Mideast is next, and, as is tediously predictable in any situation

involving the Israelis, some of the cartoon commentary inspired charges of

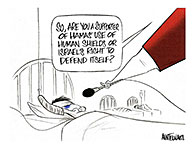

antisemitism. Writing for the Simon Wiesenthal Center, Rabbi Abraham Cooper said: "It is disgusting that the Washington Post would present an animated cartoon that is so profoundly removed from the truth. Millions of Israeli citizens—men, women, and children—have been forced into bomb shelters and safe rooms by thousands of missiles and rockets targeted at them by Hamas terrorists, whose open and avowed goal is the destruction of the Jewish state. Even Israel's enemies have recognized that Israel's military countermeasures against Hamas have included phone and text warnings as well as leaflets urging innocent civilians in Gaza to vacate the targeted areas. It is the Hamas leadership that openly uses the people of Gaza to act as human shields to protect their weapons of mass destruction. "Israelis are saddened by the deaths of four Palestinian children on a Gaza beach yesterday, but the blood of these innocent children is on the hands of Hamas leaders, not Benjamin Netanyahu," Rabbi Cooper also said, continuing: "While we regard Telnaes' right to free speech, it would be important that the Washington Post make it clear that this disgusting animation doesn't represent their views.” In her blog on July 21, editoonist Telnaes reported on her experiences after the publication of the Center’s press release: “Early last week I created a cartoon about the bombings in Gaza. In editorial cartooning, there are some topics which will result in intense reactions from certain groups, as did this one. The series of events started with the Simon Wiesenthal Center issuing a press release last Friday from which the Jerusalem Post wrote a short article titled ‘US Jews furious over Washington Post cartoon showing Netanyahu punching Palestinian infant.’ (I’ll note the JP did not ask me for a comment). So all weekend and again this morning I’ve been getting tweets and emails, some obviously group orchestrated, accusing me of antisemitism and that I support Hamas. Anyone remotely familiar with my work knows I never criticize people’s religious beliefs, only the actions of governments and the leaders of any organization which try to influence public policies that affect ordinary people’s lives.” She continued: “I’ve been in this profession long enough to know that dealing with blowback and angry reactions about a cartoon is part of the job description. However unlike my male colleagues I also am receiving sexually violent and misogynistic threats in response to this cartoon. During the Danish cartoon controversy in 2006 I maintained that regardless of what one thinks about a cartoon and its message, no one or group has the right to threaten or censor a cartoonist. You have the right to criticize, protest, or draw your own response to the cartoon—but violence and threats are not acceptable. I am a firm believer in every person’s free speech rights, regardless if a group finds the message offensive. “I’ll give the Simon Wiesenthal Center credit,” she concluded, “for acknowledging my free speech rights but they should be aware of what some of their supporters are saying in response to their press release.” In reporting the cartoon, the Jerusalem Post also noted accutely: “The caricature is aimed at apportioning blame equally between Israel and Hamas for the suffering of Gazan civilians,” an assertion that, at first blush, is difficult to reconcile with the imagery of the animated cartoon. But I noticed with a second viewing that the Hamas figure behind Netanyahu stands motionless while Bibi beats on the kid. By its very inaction in the cartoon, Hamas is complicit in the continual beating; but extending the image to the circumstance in Gaza, Hamas thus bears at least equal responsibility for what is happening in Gaza. While this may be Telnaes’ intention, in any cartoon, movement attracts a viewer’s attention, and therein lies the source of the misinterpretation of this cartoon: Netanyahu’s hitting the kid in the face gets more attention than the motionlessness of the Hamas figure—hence, the cartoon seems to be anti-Israel if not pro-Hamas. Telnaes’

last word on the subject is just at the elbow of your eye, a poignant and

therefore potent image. Telnaes is not pro-Hamas by any means. But she, like much of the U.S. press, is so disgusted by the “collateral damage” (killing women and children) of the Israeli offensive that she offers a comment that seems, at first blush, to favor Hamas. The next cartoon clockwise does somewhat the same: Tom Janssen, a Dutch cartoonist, has Netanyahu jumping right into the bloodbath in which Assad and the rest of the terrorists of the Mideast are up to their waists in. But the positions of Israel and Hamas are not morally equivalent. Hamas has been lobbing rockets into Israeli villages and towns for years. As the Denver Post said: “No nation is obliged to allow a neighbor dedicated to its destruction to fire rockets into its territory week after week, month after month, without responding.” Israel, after years of forebearance, is responding. Again. (This happened twice before, remember.) We must remember, too, as Jeffrey Goldberg reminds us in The Atlantic, that the charter by which Hamas came into being is “a frank an open call for genocide [against Jews], embedded in one of the most thoroughly anti-Semitic documents you’ll read this side of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Ultimately, responsibility for the deaths of women and children in Gaza must be shared by both Israel and Hamas: Hamas, after all—if it isn’t actually using women and children as shields as in Tim Campbell’s vividly ironic coupling of word and picture at the lower right—has stored and operated its offensive weapons from civilian population centers in Gaza. Israel can hardly return fire on its assailant without incidentally hitting innocent bystanders. Appallingly regrettable, but that, in my view, describes much of what transpires in the Mideast these days, from Syria and Iraq at one end to Egypt and Libya at the other. These people are crazed, blood-feud crazy. At the lower left of our visual aid, Pat Bagley offers an ironically sarcastic comment on the situation in Gaza, and it, like Telnaes’, inspired expressions of outrage from the Jewish communitiy in Salt Lake City where his paper, the Salt Lake Tribune, publishes. Bagley’s cartoon parallels the Gaza situation with a local problem, but even without knowing the local dimension, it’s clear that his intention is to solicit understanding for the frustration Palestinians feel in Gaza. I said “Palestinians,” not “Hamas.” Hamas is the culprit in the on-going Gaza tragedy, and its frustration is of a different kind than that being expeienced by non-combatants. Bagley was accused of “perpetuating factual misunderstandings of the conflict in the Middle East,” but his editors came to his defense. After asserting that editorial cartoons do not need to be factually accurate in order to present a commentary (indeed, all editoons are essentially one-sided arguments that never say “on the other hand”), the editor said: “I don’t think Pat’s cartoon is an example of his best work, but certainly the Middle East conflict is such a sensitive issue, it’s hard to take any kind of stand without offending someone.” Yes. And what makes it even more difficult is the atmosphere of ancient hatreds and blood-feud insanity.

LESS

INFLAMATORY perhaps are the next cartoons on the issue. Below Granlund, Nate Beller provides an ironic comment on the consequences of the coverage of the war by U.S. news media, which focuses day after day on the civilian death tally in Gaza. The image of a journalist being invaded through tunnels in his own body strenuously implies that the news media have, in effect, been compromised by those very “secret terror tunnels” that the journalist sneeringly suggests don’t exist, thus making the news media a partner in the Hamas propaganda campaign while also demonstrating that the tunnels do, in fact, exist. The Ukraine is next on this visual aid’s agenda. Left to right across the bottom, Bill Day’s two-panel cartoon offers an image of the Malaysian airplane crash site that effectively identifies the culprit by making the site a silhouette of Putin’s visage. Several other editoonists produced cartoons in a similar vein. Our final cartoon on this subject is by Shooty, perhaps a Czechoslovakian, a nearly perfect ridicule of Putin playing innocent. Finally,

a few graphic notations on other events of the past month. Alas, I can’t say the same for his caricature of Obama. Ramirez’s caricatures—of others as well as Obama— have grown progressively skinnier and skinnier. Now the faces of some are so skinny that I can hardly make out facial features. But the rest of his drawings—the equipage and machinery and landscapes—are powerfully drawn, detailed and convincing. But the skinny faces, not so much. At the lower right, Joel Pett takes a poke at the news media, a comment that is mostly verbal although his picture portrays the children immigrants in an appealing way. Finally, at the lower left, Pat Bagley deals with the Sandy Eggo - Salt Lake Comic-Con brouhaha. The Sandy Eggo Batman is overweight and pompous compared to the more muscular Salty Batman, and the latter’s female Robin merely refers to the constant evolution of comic book superheroes as they adapt to the imagined desires of new audiences—in effect, a slap in the face of the stodgy, unchanging, unadaptive Sandy Eggo posture.

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing “In these fraught times, our thoughts and prayers go out to the people of Ebola.”—Attributed to Sarah the Palin by Bill the Maher

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO POLITICAL CORRECTNESS I had a brief

career as an editorial cartoonist, drawing for the Council Chronicle, a

newspaper published for the members of the National Council of Teachers of

English. Here is one of the cartoons I did that I particularly like. The incident recorded in this cartoon actually took place (reported by Johnson biographer J.W. Krutch, as noted thereon). Little old ladies came up to Johnson after his dictionary was published and thanked him for leaving out “certain words.” And he retorted as you see here. Ostensibly, true story. And a readership of English teachers may be presumed to know this fugitive fact. (I am a Johnson nut, which is how I know it; maybe all English teachers aren’t. A risk. A gamble.) Making Johnson the first politically correct lexicographer—the verbal content here— gave the incident satirical heft. He was being PC, of course. Thoughtful of him. That he would, in the name of PC, leave words out of a dictionary is presumably a criminal act to an English teacher, the readers of the Council Chronicle and this cartoon. Hence, the barb of the satire. That many English teacher members of NCTE are liberal and, hence, advocates of Political Correctness gives the barb an even sharper point. My rabbit works as a good editoon dingbat should: he amplifies the attack, sharpens the point. In fact, here he drives the point home—perhaps a slightly different point. We have, of course, heard “those words” again and again, so leaving them out of the dictionary in a spasm of PC did no good at all. The second point on the barb. But the thing I like most about this cartoon—apart from getting Cahoots to work like Pat Oliphant’s penguin Punk—is that I got to draw one of my favorite literary folks, Johnson. Good caricature. That’s his famed biographer, James Boswell, at the right, jotting down everything Johnson says. (English teachers would probably recognize him at once just because he’s standing next to Johnson.) I love the 18th century wardrobe here—the three-corner hats, high coat collars, lacey shirt cuffs. And the two old biddies—darlin’s, both of them, and looking exactly like old biddies are supposed to look, I ween. Frilly shawls, omnibus caps. City skyline outlined in the back. Nice. Political

Correctness was all the rage twenty years ago at the time I drew the Johnson

cartoon. My opposition to the fad inspired a second cartoon, in which I

prolonged my affection for drawing costumes of the 17th and 18th century vintage. I took a particularly vicious pleasure in unhorsing the PC doctrine by having a little kid chant the obvious rebuttal. Words will never hurt me. But PC devotees steadfastly maintain exactly the opposite despite the undeniable wisdom of their childhood. I actually researched the costume, which I like, but I like even more the Sun King’s curls. The rabbit tableau, as before, adds another layer of meaning to the indictment. Teachers, the readers of this specimen, support academic freedom, but PC’s crusade against the Wrong Words has the effect of sabotaging both free speech and academic freedom. The rabbit’s exchange with the poodle emphasizes the perverse effect of PC: Academic Freedom has lost its voice—or, rather, speaks with a voice not its own. Now that I'm thinking about it, I'm not sure this cartoon was ever published. I suspect the point-of-view did not agree with the prevailing sentiment that guided content in the Council publications in those distant days. I’m not quite as determined in my objection to PC as these cartoons suggest. I think that PC, like almost anything else, can take itself to extremes and thereby lose its effectiveness. Despite the yowling kid in front of the Sun King, words can hurt. We should simply exercise a little judgement when picking the words to object to. I recall a woman whose married name was Youngman; she wanted to change it to Youngperson. That’s a little extreme in the name of PC feminism. But

editorial cartoons cannot say “on the other hand.” They cannot, as the

preceeding paragraph does, admit qualifying exceptions. Editoons make one point

at a time, the more “slam” in the body slam, the better. So I attacked PC as an

anti-social monolith. Even though it isn’t—quite. It is, however, close enough

to overweening autocracy to raise eyebrows and concerns. I did one more cartoon

on the subject. The image for this one was appropriated, borrowed, from another cartoon—perhaps the Thomas Nast cartoon at its right—and then a new caption supplied. The cartoon is, then, a “switch,” constructed by resorting to the age-old advice in how-to cartoon books that recommends taking someone else’s cartoon and giving it a new twist (hence, making it a “new” cartoon; layperson purists may think that I’m plagiarizing, but among cartoonists, “switching” is usually acceptable). As I say, my inspiration may have been the Nast cartoon, but I’m pretty sure that phrase coupled to the picture—“rule of thumb”—came from another antique artifact, a cartoon with another giant thumb that I’d seen in the old Life humor magazine. “Pretty sure” but not “absolutely sure.” I discuss switching and its co-conspirator swiping at great length in Opus 291. Both are deeply embedded in the accepted practices of cartooning. Switching and swiping. Most of the time, it’s probably okay. Charlie Brown shows up often in editoons as the icon of The Loser. Is that a swipe? Or has Charlie simply become a cultural fixture. My switch—or swipe—includes a drawing that’s distinctly my own and the application of the phrase and image to a idea different from my source. More switch than swipe. Or so I say. But I would, wouldn’t I?

ANY TIRADE on PC these days is bound to bring us to the Washington Redskins and the much-publicized debate over whether the name of the team’s mascot is offensive and ought to be discarded. Or “retired.” The team’s owner, Daniel Snyder, thinks the name is honorific, but some Native Americans disagree. One side of the debate was represented in the Denver Post by a retired newspaper editor, Dick Hilker, whom we quoted last time: “We should assume that intentions are the highest when school nicknames and mascots are chosen. ... No teams are named Wimps, Weasels, Nazis, Thieves or Hornswogglers.” Ergo, Redskins is not a derisive name. It is doubtless intended to conjure up fantasies of determined warfare, the sort of sporting endeavor we find on the playing fields of America. (Why not change the name to Washington Warwhoops? Probably a better alternative than Injuns.) I

thought I could leave the dispute right there. And then I remembered a cartoon

by Milt Priggee that we’ve posted at your eye’s elbow. Or does Priggee’s cartoon make Hilker’s point? On Priggee’s parade of helmets, “Redskins” seems to stick out as not being in the same class as “Krauts,” “Spades,” and “Wetbacks.” If Redskins seems out of place here, it may be because we’ve become inured to the derogatory connotations of the word. Priggee certainly thought “Redskins” was as much a slur as “Wetbacks.” Hilker and Priggee seem to make the strongest cases for opposite sides of the argument. And I don’t know where I stand on the issue. Both advocates make perfectly good sense to me—even though the argument itself seems a little silly and self-absorbed. Is “redskin” in the same class as “nigger’? The latter carries a load of historic cruelty and abuse. Is the former freighted with anything similar? And what about “injun”? In an article he wrote years ago to encourage aspiring young editorial cartoonists, Priggee talked about his “earliest recollection of a newspaper cartoon.” It was a cartoon by John T. McCutcheon, the fabled editoonist at the Chicago Tribune. Entitled “Injun Summer,” it’s posted hereabouts.

The cartoon was such a favorite with readers that it was reprinted every autumn (until recently) since it first appeared in 1912. So where does that leave us? Awash in sentiment, as usual, and that’s why resolving the Redskins predicament is so difficult. Sentiment rules where reason has fled. But I’m not so sure that sentiment isn’t the superior of the two. If so—particularly since even Native Americans are not all, universally, opposed to “Redskins”— it’s Hilker over Priggee.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. RECALL has reached its nadir. The latest product to be recalled is the Spencer Bar Stool with four legs, a padded seat and back. It’s being recalled because “the footrest can crack, compromising the strength of the bar stool, posing a fall hazard.” There are only about 800 of these stools, and no falling incidents have been reported. At least, no one has fallen because of a cracked footrest. But it’s hard to maintain a straight face about this threat to life and limb. If falling hazards are a major concern with a bar stool, whither are we bound? What’s next? Why, the bar itself, I suppose. And after that, the booze that passes over the bar to the guy sitting on the Spencer Bar Stool, oblivious, no doubt, that stool, bar, and booze constitute a falling hazard.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping THE SANDY EGGO COMIC-CON made it into the newspaper funnies during the week of the Con—and, in a couple instances, in the weeks before. Francesco Marciuliano and Jim Keefe might be alluding to the Con in Sally Forth as the characters discuss Afterlife with Archie. But Greg Evans is unabasedly touting the Comic-Con in the Luann release the Sunday before the Con commenced.

And Patrick McDonnell spent the whole week of the Con celebrating superheroes by having his squirrels in Mutts drop nuts on them. Jeff Keane gestured in the direction of Sandy Eggo with his Family Circus release on the Con’s Friday. He had prints of the cartoon shown here that he was selling at the booth of the National Cartoonists Society.

But Tom Batiuk in Funky Winkerbean plunged into the vitals of the Comic-Con for more than a week, resuming the story of Holly Winkerbean looking for a copy of the fictitious Starbuck Jones No.115 to complete her stepson’s collection of the title. (For the whole story of this expedition’s origin, see Opus 327.) The grand finale appeared on Sunday, July 27, the last day of the Con—when Funky Winkerbean depicted the cover of the scarce comic book (drawn by Michael Golden, one of several comicbook veterans Batiuk recruited to visualize his made-up comic book).

THEN JUST FOR

THE FUN OF IT—of looking at and seeping happily into—here are some strips I

particularly enjoyed lately. But the genuine pleasure today is in Greg Evans’ Luann, wherein T.J. proves that a cartoon hat still springs into the air when its cartoon wearer is surprised. We’d thought that simple and charming device evaporated long ago, but we’re delighted to have it revived in so distinguished an enterprise as this strip. Below that, a couple panel cartoons. On the left, another of John McPherson’s exercises in bad taste. On the right, a truism for all ages. Well, for my age anyhow.

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

“Gahan Wilson: Born Dead, Still Weird” Documentary film by Steven-Charles Jaffe A DOCUMENTARY FILM is not, of course, a book, so a review of it is a little out-of-place here. But Wilson is a cartoonist of extraordinary talent and a joyfully perverse albeit pervasive humor, so I’ll take notice of the film here regardless of how inappropriate this venue may be for doing so. I watched the film on Amazon Instant Video, and I’m sorry to report I was disappointed. Not terribly disappointed; just a little but enough to feel it. The film is an entertaining 45 minutes, but it isn’t as informative as I’d hoped (although what I’d hoped, I can’t say exactly). The best part of the film is a segment at the office of The New Yorker’s cartoon editor, Bob Mankoff, where he receives cartoonists peddling their wares every Tuesday morning. As Lloyd Sederer said in his review in Psychology Today: “One by one, each cartoonist unveils a batch of drawings and waits to be impaled upon the sharp words of the editor, whose whimsy will determine their fate. It is just like the terrifying world of grownups in a Gahan Wilson cartoon.” Mankoff being something of a show-off, I suspect that the presence of a recording camera in his office stimulated him to displays of cruel wit that he might not otherwise have perpetrated. Otherwise, the film is a rather routine exposition. Wilson talks about his life, his birth and his trying parents. He was born dead in the American mid-west in 1930, Sederer reports: “He was blue and not breathing at birth from the anesthesia administered to his mother. A pediatrician happened on him before he was placed in a casket and held him under cold water until he revived. It seems as if he has spent a lifetime embodying this moment as metaphor in his dark, shocking, and ultimately life affirming art.” Wilson also talks about his cartoons and we watch him coloring a couple. Otherwise, the film is a compilation of testimony to Wilson weirdness from the likes of David Remnick, Roz Chast, Stephen Colbert, Guillermo del Toro, Hugh Hefner, Bill Maher, Stan Lee, Randy Newman, Gahan’s wife, and a few others. You can find out more about Wilson by reading Gary Groth’s interview with him in Fantagraphics’ Gahan Wilson: Fifty Years of Playboy Cartoons published in 2011 (some of which is rehearsed in Collector’s Corniche down the scroll). The film can be viewed on iTunes. Xbox Video, Playstation, Google Play and Vudu.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE When someone asks you, “Penny for your thoughts,” and you put your two cents in, what happens to the other penny? Why is the man who invests all your money called a broker? Why are a wise man and a wise guy opposites? Why do croutons come in airtight packages? It’s just stale bread to begin with. Why do overlook and oversee mean opposite things? If horrific means to make horrible, does terrific mean to make terrible?

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year: 2014 Edition Edited by Dean P. Turnbloom 208 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w; Pelican paperback, $14.95 THIS COLLECTION has been an annual fixture since 1972, and all but the last two of the 43 volumes were edited by Charles Brooks, a conservative editorial cartoonist at the conservative Birmingham News and a stalwart of political cartooning in the South. Editorial cartoonists, most of whom skew liberal, often criticized Brooks’ selection for its rightward lurch. But neither of the last two books are guilty of that sin. Editoonist Steve Kelley, late of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, edited last year’s collection of 2012 cartoons, determined to make the book live up to its title without political bias; and he succeeded (see Opus 305). And this year’s effort—as usual, a compilation of the cartoons of the year prior to the year named in the title—likewise avoids the bias of the Brooks years: 25 cartoonists are represented with the allowed maximum of 5 cartoons each, and only 6 of those are conservative; 3 of the rest are neither liberal nor conservative, leaving 16 liberal voices. A liberal bias in an annual compendium is more acceptable than a right-leaning one because, as Ijust said, most of the profession veers off leftward. Turnbloom has returned to Brooks’ policy of limiting submissions to five from each cartoonist (Kelley imposed no limit) with the result that more cartoonists can be represented in the book’s allotment of pages. Admirable though Turnbloom’s impulse may be, the more cartoonists, the greater the chances of including some who are scarcely ready for prime time: of the 132 cartoonists represented herein (Kelly’s book had only 110; Brooks’, typically around 140), roughly a quarter probably should not be here either because the art is feeble or the commentary lacks the kind of vigor we expect in anything denominated “the best.” Still, some of these virtual unknowns hit pretty hard in the cartoons Turnbloom picked. Turnbloom was probably urged by Pelican to include a goodly number of less well-known cartoonists in order to convey a (faux) impression of all-inclusiveness; Kelley avoided that pitfall. As a condition of accepting the editorship last year, Kelley imposed no limit on submissions because, in effect, “the best” knows no limit—so why should a book of “the best”? Of

the prime-time cartoons, Turnbloom’s selection includes some happily

hard-hitting cartoons, many with inventive visual metaphors. Nearby, we’ve

posted four representatives—all of which deploy powerful images to make their

points— Paul Fell’s handgun shooting the owner not in the foot but in

the face (with presumably the same effect as a foot shot), Robert Arial’s adapting Benjamin Franklin’s famous dissected snake and slogan for the

present-day pachyderm party’s problem, Milt Priggee at the lower right

with a stunning metaphor that combines two problems with a vivid albeit

suitably bizarre solution, and, finally, at the lower left, Adam Zyglis’s deft

depiction of the reason for Congress’s failure to act (they are all too eager

to assign blame instead of seek solutions). The book also includes the work of several noted cartoonists who were regularly excluded from Brooks’ books—Ted Rall, f’instance, and Tom Tomorrow (whom Turnbloom identifies as Dan Jenkins, not Dan Perkins, Tom’s real name); and Matt Bors. Nothing, though, from a recent winner of several awards, Jen Sorensen; maybe next year. That so many of the cartoons are unabashed assaults is doubtless due to the year being crammed with so many political events (or, more aptly, non-events) deserving of roaring ridicule, editorial cartoons being better suited to attacking than to defending or championing. In 2013, political malfeasance was so rampant that mounting cartoon attacks was as easy as rolling a pencil off a tilted drawingboard. As usual, the book’s contents are organized into chapters, each of which brims with several wickedly pointed cartoons that tend to overpower the lame ones. . In the Obama Administration chapter, Obama is critized for obliviousness about NSA spying, drones, IRS and Obamacare. In this last, the ACA itself is criticized in only three cartoons; mostly, it’s the politics of Obamacare that is ridiculed—bad roll-out and Obama’s lie. The GOP is faulted for doing nothing to fix what they allege is wrong and for repeated ineffectual votes to repeal it. In the Congress chapter, the Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm is attacked mercilessly. Everyone dumps on them, but the Tea Party is not mentioned in this chapter. In Immigration, the GOP is at fault. In Government Shutdown, editoonists again gang up on the GOP (except Lisa Benson, who is against raising the debt limit). In Foreign Affairs, Obama is seen as weak or inept on Iran, Syria, Putin, Snowden, North Korea, and Egypt; but why waste space on such a trivial foreign affair as Toronoto’s madcap drugged-out mayor Rob Ford? In the Politics chapter, both parties are drubbed for failure to serve; in Spying, more on NSA than Snowden. The Media/Entertainment chapter is critical of the news media (which is always called just “media” as if other non-news elements of the media are nonexistent) for a preoccupation with trivia. (And then, herein, we have Rob Ford.) In Society, topics include social media, bullying, voting rights, NSA, and abortion (two anti-abortion; one for). Under Other, we find rape in the military, three on the death of Roger Ebert (Nelson Mandela gets only six but has a chapter to himself). The annual award winners (Pulitzer, Herblock, etc.) are showcased in the book’s opening pages, and at the end, all Pulitzer and SDX winners are listed in chronological order. Turnbloom is not new to his task: he’s edited several annual compilations of “prize-winning cartoons” for Pelican. His biographical information indicates that he was once an editoonist himself, but scouring the Web turns up no physical evidence of this aspect of his life. Nowadays, he writes fiction of the macabre sort, including Sherlock Holmes and the Body Snatchers and Sherlock Holmes and the Whitechapel Vampire. Interviewed a year or so ago about his editing of the Prize-Winning volumes, Turnbloom said: “A good political cartoon, a really good one, should cause the reader to look at an idea in an unexpected way, a way that the reader wouldn’t normally think about. Whether they agree or not, they at least for one moment realize a new perspective. A good political cartoon should have something to say about an event or idea and not just celebrate it. ... More than providing a comic headline, cartoons should, in my opinion, provide commentary, pointing out the foibles and the folly of serious topics in a unique and unusual way.” He said he “gravitates” toward the “outliers that pick up an idea missed by their colleagues,” but he confessed that in his own editorial cartooning career, he “fell into the trap of seizing the low-hanging fruit—it’s so tempting.” You’ll have to see the book to see if he succeeds in avoiding the low-hanging fruit in favor of the outlier. Here are a few more of his picks that I think are heavy hitters.

The first four, I should point out, are by cartoonists not particularly well-known, yet each of them makes effective use of imagery to make memorable statements. The second group, all by more notorious editoonists, also offers powerful commentary through imagery—Mike Luckovich’s departing wedding couple, Kevin “Kal” Kallaugher’s pinnacled inequalities. I especially like Chris Britt’s at the lower right: the little Tea Partier is so obviously having a terrific time blowing up the government and all the rest of American institutions; the expression on his face is perfect and makes the cartoon very effective. Bruce Plant’s gun salesman presents no metaphor, but the juxtaposition of the words in the setting are telling.

IRKS & CROTCHETS From Harper’s Index: Maximum number of dilos a Texan may legally own: 5 Chance that a pregnant U.S. woman says she is a virgin: 1 in 125 Number of states in which it is a felony for an HIV-positive person to spit on a police officer: 5 Percentage change in the past five years in the portion of Republicans who believe in evolution: -26 Portion of U.S. students who started college in 2007 who have not completed their degrees: 1 / 2 Portion of the thirty professions projected to grow fastest over the next ten years that require postsecondary education: 2/ 3

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Welcome to our sentimental section where I muse and marvel about antique volumes on the shelf and rare finds in old bookstores and the like. Nothing major. Skip over this if you’re busy.

AS YOU MIGHT

EXPECT, I dote on old cartoons. And to find them, I periodically browse issues

of old magazines. During one of those rituals, I found in a 1956 Collier’s the

cartoon at hand, undoubtedly one of the earliest Gahan Wilson cartoons,

published (as it sez there) in August 31, 1956, well over a year before Wilson

became a regular at Playboy. (His first cartoon for Playboy was