|

||||||||||

Opus 308 (April 10, 2013). Sensations and reviews dominate this trip down the rabbit hole: Israel jails Arab cartoonist without charges, DC Comics backs off hiring an anti-gay guy to write Superman, Chicago Public Schools bans Persepolis, Siegel heirs lose again, Chicago Trib drops Shoe, Blondie returns to Duluth, some of the best editoons of the month, plus reviews of a dozen new books(including vintage crime and horror titles and the latest Peanuts reprints), and obits for Carmine Infantino and Bob Clarke. We also explain how Superman destroyed the infant comic book industry and offer a few other tasty dollops of comics history. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Another Wimpy Kid New Animated Mickey Mouse Israel Jails Arab Cartoonist More Comics Than Ever for Free Comic Book Day Chicago Schools Bans Persepolis; Then Lifts Ban Siegel Heirs Lose Superman—Again DC Comics Shelves Superman by Anti-Gay Marriage Writer Chicago Tribune Drops Shoes Is Print Dead or Not?

BLONDIE’S BACK IN DULUTH Interview with Dean Young, the Strip’s Manager

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Pluggers and the Reign of Animals in Strips Also Zombies in Funnybooks

EDITOONERY GOP’s Search for New Identity Guns Some More Others of Some of the Best Editoons of March

BOOK MARQUEE: Brief Reviews Icons of the American Comic Book Silver Streak Archives, Vols. 1 and 2 (Also: How Superman Changed the Audience for Comic Books) Crime Does Not Pay, Vol.3 Adventures Into the Unknown: Pre-code Horror Forbidden Worlds, Vol.1 The Best From the Tomb Ditko Monsters: Gorgo!

The Complete Peanuts: 1985-1986 & 1987-1988 From the Files of Mike Hammer

BOOK REVIEWS The Golden Age of DC Comics: 1935-1956 (EC HQ on Lafayette Street in New York) American Comic Book Chronicles: 1960-65

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Snapshot, No.1 Sledgehammer 44, No.1 Sex, No.1

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY OrsonWelles on Horror Comics/Movies

PASSIN’ THROUGH Carmine Infantino, 1925 - 2013 Bob Clarke, 1926 - 2013

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

The Sunday supplement Parade published one cartoon in the issue for March 24; the magazine has gone for at least a month without any manifestations of its “Cartoon Parade,” and one cartoon is hardly a “parade”; too bad. The next week, no cartoon at all. Another venue evaporating. ... The eighth title in Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid series will be published by Abrams's Amulet Books imprint in the U.S. in November, with near-simultaneous publication in seven additional countries: the U.K., Australia, Germany, Greece, Japan, Korea, and Norway. "Never in my wildest dreams did I think that Greg Heffley's stories would be enjoyed by this many kids around the world," said Kinney in a statement. More than 85 million Diary of a Wimpy Kid books are in print in more than 44 territories; the three Wimpy Kid movies, based on the first three books in Kinney's series, have grossed more than $250 million worldwide. All

of 19 new 2D Mickey Mouse cartoon shorts will premiere June 28 on Disney

Channel, online, and in Disney apps, reported icv2.com. Each episode takes

Mickey to a different locale—Santa Monica, New York, Paris, Beijing, Tokyo,

Venice and the Alps; in each, he faces "a silly situation, a quick

complication, and an escalation of physical and visual gags." Other

classic Disney characters such as Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, Daisy Duck, Goofy

and Pluto will also appear, with an "occasional homage to other icons from

the storied Disney heritage." You can

Israel

Jails Arab Cartoonist. A Palestinian editorial cartoonist, Mohammad Sabaaneh, was arrested by Israeli

police on February 16 as he was crossing the border from Jordan to the West

Bank. Denied access to an attorney, he is being held without charge, and his

detention was recently extended to give Israeli authorities time to decide what

to charge him with. He cartoons for Al-Hayat al-Jadida, the official

newspaper of the Palestinian Authority, and it seems probable, as Daryl Cagle at

Cagle Cartoons in the U.S. says, that Sabaaneh is being held “to

A Bonanza of Free Comic Books. This year’s Free Comic Book Day, May 4, is likely to give away more comic books than ever before. For the 12th year of the event, hosted by comic book shops and specialty stores in 46 countries, Diamond Distributors reports that orders from nearly 2,000 retailers across the country have topped more than 4.6 million comics, a record. That’s up 31.4 percent from 2012 when orders tallied 3.5 million, saith apnewsarchive.com; the year before, a mere 2.7 million books were ordered. Although the comics are given away to customers, the stores hosting the event must buy them—this year, 53 titles from publishers big and small, most of whom print special promotional editions of forthcoming comics. This year, the National Cartoonists Society is getting into the act, reported Tom Richmond, NCS prez. “We’re asking members to use their strips and comics to promote comic books and FCBD on the day or days leading up to the event this year,” he said. “Whether it’s a mention in your daily, promotion of the event in your comic publication, or reaching out to fans and readers on your website or through social media, this is a fantastic program to encourage readers young and old to stop in their local comic book shop, get a free comic book and see what the world of comics and cartooning has to offer and interest them.”

Chicago’s Schools Screw Up Again. Chicago’s public school administration looked as embarrassed at the end of March as it looked at mid-month when it was reported that Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, her award-winning memoir about growing up during the Iranian Revolution, had been removed from both district libraries and classrooms. Widespread criticism and protest ensued. The American Library Association said the removal of the books from students' hands "represents a heavy-handed denial of students' rights to access information, and smacks of censorship.” Chicago Public Schools (CPS) soon backtracked, saying that the memoir was to be removed from only seventh grade classrooms and not from libraries, because "it contains graphic language and images that are not appropriate for general use in the seventh grade curriculum.” Accompanying the reinstatement was a clarification from CPS CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett: “Let me be clear—we are not banning this book from our schools," Byrd-Bennett said in her memo to principals. "It was brought to our attention that it contains graphic language and images that are not appropriate for general use in the seventh grade curriculum…Due to the powerful images of torture in the book, I have asked our Office of Teaching & Learning to develop professional development guidelines, so that teachers can be trained to present this strong, but important content." Chicago Teachers Union spokesperson Stephanie Gadlin dismissed the backtracking as "Orwellian doublespeak", pointing out that "unfortunately 160 elementary schools don't have libraries – and they know that." CTU's financial secretary Kristine Mayle added that "the only place we've heard of this book being banned is in Iran. We understand why the district would be afraid of a book like this – at a time when they are closing schools – because it's about questioning authority, class structures, racism and gender issues," Mayle continued: "There's even a part in the book where they are talking about blocking access to education. So we can see why the school district would be alarmed about students learning about these principles." Satrapi herself, speaking from her studio in Paris to the Chicago Tribune, said the restriction was "shameful" and dismissed the CPS's concerns about what it had described as "powerful images of torture": Said Satrapi: "These are not photos of torture … seventh graders have brains and they see all kinds of things on cinema and the internet. It's a black-and-white drawing and I'm not showing something extremely horrible. That's a false argument. They have to give a better explanation," said Satrapi.

Here are some pages from Persepolis. Which are depicting torture?

Superman and Siegel Heirs and On and On. The heirs of Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel seem determined to spend the rest of their lives in court. Kevin Melrose at robot6.comicbookresources.com reported that a federal judge confirmed March 20 that the heirs relinquished any claims to the character in a 2001 agreement with DC Comics when they accepted an offer that permits the publisher to retain all rights to Superman (as well as Superboy and The Spectre) in exchange for $3 million in cash and contingent compensation worth tens of millions. But the Siegel attorney Marc Toberoff is unwilling to give up and introduced a new strategy, arguing not only that a previous ruling didn’t settle all of the outstanding issues but that if there was a contract, then DC failed to perform: “DC anticipatorily breached by instead demanding unacceptable new and revised terms as a condition to its performance; accordingly, the Siegels rescinded the agreement, and DC abandoned the agreement.” Despite an obvious eagerness to conclude “this chapter of the continuing Superman saga,” the judge noted there remain “lingering issues” regarding Superboy and early promotional ads for Action Comics No.1. Wright ordered that DC and the Siegel family file briefs by March 28 addressing how the previous ruling affects their respective rights to those works. To which Allan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com responded in the only way sober, responsible people can: “I completely understand DC’s position of wanting to keep ownership of the cash cow and the Siegel heir’s desire own a piece of that cash cow, but I have Superman litigation fatigue.” Ditto.

The Gay Kerfuffle at DC Comics. Last month, DC Comics found itself smack in the middle of a brouhaha possible only in free-speech loving America. The publisher planned to issue a digital comic entitled Adventures of Superman and follow the ethereal publication with a print version. But when the writer of one of the Adventures stories was announced, the ether turned lethal. The writer, Orson Scott Card, author of the sf End Game series, is a noted homophobe, (“sorry—‘gay marriage opponent’ as wire.com put it), and when his presence on the project was announced, the social media panicked in all directions at once. Within days, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender activist website AllOut.org collected more than 11,000 signatures on an online petition asking DC to drop Card from the project. "By hiring Orson Scott Card despite his anti-gay efforts, you are giving him a new platform and supporting his hate," the petition reads. "We need to let DC Comics know they can't support Orson Scott Card or his work to keep LGBT people as second-class citizens." Card, who is on the board of directors of the National Organization for Marriage, has written many essays on the subject, including a particularly nasty one in 2004 that likened marriage equality to the end of civilization, wrote Brian Truitt at USA Today. “In 2008, after court decisions in California and Massachusetts allowing gay marriage, Card wrote a column for Mormon Times that said in part: ‘How long before married people answer the dictators thus: Regardless of law, marriage has only one definition, and any government that attempts to change it is my mortal enemy. I will act to destroy that government and bring it down, so it can be replaced with a government that will respect and support marriage, and help me raise my children in a society where they will expect to marry in their turn.’ At first, DC reacted to all the excitement with a statement: "As content creators we steadfastly support freedom of expression, however the personal views of individuals associated with DC Comics are just that — personal views — and not those of the company itself." Truitt continued: “The publisher has a history of being pro-LGBT with its series. Batwoman, featuring a strong and nuanced lesbian superheroine who shares the Gotham City streets with Batman, has won two GLAAD Media Awards for outstanding comic book and is up for a third this year. That's partly why some comics readers have difficulty understanding the Card hiring.” Card has written comics before, and others in the industry expressed the available range of opinions. "Petitioning to have writer Orson Scott Card fired for his social views is as fascistic as politicians condemning a sexual preference," tweeted Mark Millar, a writer for Ultimate Fantastic Four, Kick-Ass and Wanted. Comic-writer Jim McCann, who is openly gay, says, "A company has the right to hire whomever they choose ... and Mr. Card has the right under the First Amendment to freely speak his beliefs, no matter how hateful and archaic they may be. In turn, however, the fans have the same right to express their disappointment and outrage against his hiring.'' So far, I agree with both. But Millar is on the side of the angels. Those who support gay rights (among whom I count myself) do so, I assume, at least partly because they believe we’re all equal and are therefore entitled to the same rights. They are, ipso facto, against any effort to deprive anyone of rights enjoyed by others. To march against Card in this case is to enlist in the ranks of their opposition, those seeking to deny equal rights. A delicious but terrible conundrum. But the irrationality of the fussing didn’t stop it. Comic-shop retailers jumped into the fray, according to Truitt. Richard Neal, owner of Zeus Comics in Dallas, announced on his Facebook page that the store would not carry the print edition of Adventures of Superman that contained Card's 10-page story. "It is shocking DC Comics would hire him to write Superman, a character whose ideals represent all of us," Neal wrote. "If you replaced the word 'homosexuals' in his essays with the words 'women' or 'Jews,' he would not be hired. But I'm not sure why it's still OK to 'have an opinion' about gays. This is about equality." Brian Hibbs, owner of the San Francisco store Comix Experience (and instigator of Free Comic Book Day), agreed with Neal's position and believes there'll be more shops following suit. "There's a comic shop in the Castro, which is a gay neighborhood in San Francisco. I wouldn't be surprised if that store isn't carrying the book," said Hibbs, adding that he'll probably stock it to the same extent that he does other digital-first comics. "I might order one or two copies and then by the third or fourth issue we won't be selling it anymore because no one is buying it." In the midst of all the media noise on the issue, the artist who was to draw Card’s story, Chris Sprouse, announced that he was withdrawing from the project. Graeme McMillan at Wired.com took up the story: “It took a lot of thought to come to this conclusion,” Sprouse explained. “The media [attention] surrounding this story reached the point where it took away from the actual work, and that’s something I wasn’t comfortable with. My relationship with DC Comics remains as strong as ever and I look forward to my next project with them.” Of this action, DC said: “We fully support, understand, and respect Chris’s decision to step back from his Adventures of Superman assignment. Chris is a hugely talented artist, and we’re excited to work with him on his next DC Comics project. In the meantime, we will re-solicit the story at a later date when a new artist is hired.” And

the story appears to be on permanent hold, reported McMillan: it “will not

appear in either the digital or print editions of Adventures

of Superman, the upcoming anthology series launching later this year;

instead, it will be replaced by a story by respected creators Jeff Parker and

Chris Samnee, with the print edition featuring the Parker/Samnee collaboration

in addition to work by Justin Jordan and Riley Rossmo, as well as Jeff Lemire.

Because of this last-minute substitution, the first print issue of Adventures of Superman will be made returnable to

comic stores that have already ordered it.” The news has inspired speculation about whether or not this could mean that DC will quietly kill off the controversial Card story entirely, with some suggesting that the story remaining un-illustrated gives the publisher an “out” to avoid any potential breach-of-contract legal response. (As a freelancer, however, Card wouldn’t have the option of a wrongful termination suit.) Although attorney and frequent comics legal commentator Jeff Trexler told Wired that according to New York law, “firing an employee with religious-based views against homosexuality creates the sort of legal conundrum that would make a computer blow up on classic Star Trek,” this doesn’t appear to be the case for the Card story. A statement from DC Entertainment on the issue specifically mentioned that the publisher “will re-solicit the story at a later date when a new artist is hired.” Of course, finding an artist willing to work on the story after it has provoked online petitions and outcry against Card’s hiring in the first place may be easier said than done. The now non-homophobic Adventures of Superman No.1 will be launched digitally on April 29, with the print edition following on May 29. It’s unknown whether the stores that were planning to boycott the issue or donate their proceeds to LGBT charities will continue to do so in light of this development. So who won? Is this a victory for gay rights or for fascist suppression of dissenting views? Or for the whimsies of the marketplace? I say the latter—and the marketplace has always been fascistic in the realm of the almighty dollar.

Trib Gives Shoe the Boot. The Chicago Tribune has dropped Shoe, the Reuben-winning comic strip created in 1977 by the late Trib editorial cartoonist Jeff MacNelly, who wrote and drew the strip until his death in 2000. Geoff Brown, the paper’s entertainment editor, was, as is usual in such cases, stand-offish about why. Jim Romenesko says he asked Brown to explain the decision to drop its legendary ex-cartoonist's creation, and Brown e-mailed back: "The Chicago Tribune continuously aims to enhance the reader experience by making improvements to content offerings. In an effort to provide fresh humor and interactivity, we're adding a crossword puzzle, trivia game and new cartoon." Romenesko asked how Shoe did in reader surveys. Said Brown: "Our customer reader research is proprietary, so I can't share the data with you." In other words, the usual horseshit. The Trib became famous here at Rancid Raves for its temporizing tactic in responding to reader complaints when a strip is dropped. The policy was to say that the strip in question was only temporarily being dropped as an experiment but would probably return in a few weeks. The reader was placated and hung up the phone, leaving the editor alone; but the paper never intended to reinstate the strip and never did. Since

MacNelly’s death, the strip has been continued by Gary Brookins and Chris

Cassett (until his death a few months ago) and MacNelly’s widow, Susie.

PRINT AIN’T DEAD YET. OR IS IT? Everyone is expecting the print media to collapse within our lifetime, but maybe not. “In North America, where the recession bit deepest, more new magazines were launched than closed in 2011 for a second year in a row,” saith The Economist, quoting the Association of Magazine Media which reports “that magazine audiences are growing faster than those for tv or newspapers, especially among the young.” The reason? “Unlike newspapers, most magazines didn’t have large classified-ad sections to lose to the Internet, and their material has a longer shelf-life.” Magazines do a good job of inspiring your dreams,” said David Carey, boss at the Hearst works. Magazines also specialize, aiming at niche readership. And that helps. But try telling Bill Heasty, who started a chain of magazine, newspaper, and book stores in Denver 40 years ago and will close the last of his 5 stores at the end of April because there’s no longer a living in it. His stores once carried everything—from obscure trade magazines on cult tv, marijuana and Mormon living to survivalist guides and auto repair manuals. At the peak of his chain’s operation 20 years ago, Heasty sold 4,000 publications and 150 Sunday newspapers from around the world, including at least one from every U.S. state; now, he sells just a handful of local papers and a few from the East Coast. In its best years, his stores employed 35 people, turned $5 million in annual revenues and saw 1,500 paying customers every day. Now Heasty employs just two part-timers, made just $396,000 in revenue last year, and sees only about 36 customers a day. He closed is first store in 2000 and kept postponing decisions to close the others, but he had to give them up, one after the other. And now, at the end of April, the last of them will be shuttered. Ironically, reported Kristen Leigh Painter at the Denver Post, “just this week, a city of Westminster representative walked into the store and handed Heasty a trophy to celebrate 25 years of being in business in the city.” Said Heasty: “I don’t think I’ll make it to 26.”

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “Safety is all well and good. I prefer freedom.”—E.B. White in The Trumpet of the Swan “Piglet was so excited at the idea of being Useful that he forgot to be frightened any more.”—A.A. Milne in Winnie the Pooh “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boasts.”—Kenneth Grahame (as Ratty) in The Wind in the Willows “Nothing cures homesickness quicker than an unexplored tower.”—Nancy Willard in Beauty and the Beast All the foregoing, as you might have guessed, are lifted from a single source, the irrepressible What the Dormouse Said: Lessons for Grown-ups from Children’s Books, collected by Amy Gash.

BLONDIE’S BACK Last time, in Opus 307, we related the sad story of how the Duluth News Tribune dropped Blondie in January. Now, we’re jubilant to report that Blondie is back in Duluth. And here’s Robin Washington, the paper’s editor, who explains to his readers how that happened (in italics): Two weeks ago, I announced the News Tribune was canceling the comic strip that’s run in the paper since 1937; not because of its quality, but because of how much we were being charged for it — about twice as much as for any other strip. We were unsuccessful in our attempts to renegotiate the rate with King Features Syndicate, which distributes it, so in its place would run Pearls Before Swine, a popular strip from a different syndicate offered at a very reasonable rate. Though many readers wanted Blondie to stay, the response to my explanation was overwhelmingly supportive. “I like Blondie in the comic strips, but I don’t like the poor service you described from your syndicate provider,” wrote one reader. “Maybe a cancellation will get someone’s attention.” It did, and the salesman from King Features Syndicate, which handles Blondie, e-mailed the next morning. And phoned. Though he and I will have to agree to disagree about who was supposed to call back whom in our previous negotiations, we both wanted to return Blondie to Duluth and struck a deal we both could live with. The result is she’s back on page A11 today and, because the Sunday comics section is printed ahead of time, will return on Sundays beginning March 3.

WASHINGTON THEN PHONED Dean Young, who, as the son of Blondie’s creator Chic Young, inherited the strip when his father died in 1973. Dean doesn’t draw the strip: that’s done by John Marshall, who joined Dean in 2002, after his predecessor, Denis Lebrun left, and (mostly these days) Marshall’s assistant Frank Cummins. (For several decades, Blondie has enjoyed the deepest art bench of any comic strip: the artist whose signature appears next to Dean’s on the strip is perpetually training his successor, who, as the apprentice, winds up doing most of the drawing as he trains but none of the signing.) Dean doesn’t think up all the strip’s gags either: he works with at least one gag writer, maybe more. In effect, Dean is Blondie’s “manager,” selecting the jokes and approving the drawing. But in interviews, Dean pretends he’s the strip’s cartoonist. Here’s Washington’s report on his interview with Dean—: Dean Young started working on “Blondie” in the early 1960s, then under the tutelage of his father, Chic Young, who created the strip. At Chic Young’s death, Dean took over and, after a rocky start, saw it running in more than 2,000 newspapers. The following is edited from a phone interview with Young. News Tribune: How old is Blondie? Dean Young: She’d be about 84. She keeps looking better and better. She’s never had a facelift. She’s been able to update herself. That goes for the humor as well. The humor is more sophisticated and more complex. DNT: You still use a lot of the same gags. Dagwood is still running for the bus. DY: No, no, no, no! Shame on you! That bus went out a long time ago. We’ve got a car pool now, which is a lot more fun. With four people in the car pool, you’ve got a lot more sources of gags. When we talk about her being 84 years old, you have to fight hard not to be an anachronism. They did a Blondie postage stamp one year. If you look at all of the comic characters they chose, Blondie is the only one that is still a viable comic strip. There’s something to be said for that durability. We’ve just kept up with the times. DNT: How about yourself growing up? What impact did the strip have on you? DY: I wanted to be something else. I wanted to own an ad agency. I can’t believe I was thinking that. DNT: You went into it? DY: Oh, yeah. So my dad invited me to come back. I couldn’t get my stuff packed soon enough. He was my mentor, my teacher, and my father. He taught me everything about how to run a comic strip. He taught me some things that I had to part ways with him on, that seemed old fashioned. DNT: Every good mentor-protégé relationship has a point where the protégé goes out on his or her own. DY: When he died, (hundreds) of newspapers dropped the comic strip on the basis of his death. I was having trouble and I remembered him telling me “just do what you think is funny.” I had to do something different and I did. I introduced a few new characters, and, of course, the car pool. One of the big events was Blondie going to work. There’s a place I got some more fallow ground to work with. I think a lot of women can relate to Blondie in that regard. DNT: Where do you see newspaper comics 10 years from now? DY: I think newspapers will be around. I just like the tactile feeling of holding that paper. I wish, though, that newspapers could get the idea that comics are a big factor that could be more of a help to them. I think it’s the only place in the paper that you can entertain people. DNT: What strips do you like other than your own? DY: Jim Davis (Garfield) and Mike Peters (Mother Goose and Grimm) do good work. DNT: What don’t you like? DY: In Blondie, a hand is drawn like a hand. It’s all anatomically correct. People can relate to the fact that it looks real to some extent. DNT: So you don’t like the ones who don’t do that. Who? You can name names. DY: I’m not going to do it! I know those guys! DNT: In your updating, would you ever change Mr. Dithers’ attitude toward Dagwood? DY: No, not at all. He’s still trying to get the same raise. He’s never going to get it.

READ AND RELISH More from What the Dormouse Said: “Trouble can always be borne when it is shared.”—Katherine Paterson, The Tale of the Mandarin Ducks “After all, the best part of a holiday is perhaps not so much to be resting yourself, as to see all the other fellows busy working.”—Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows “What you can do is often simply a matter of what you will do.” —Norton Juster, The Phantom Tollbooth “We never know the timber of a man’s soul until something cuts into him deeply and brings the grain out strong.”—Gene Stratton Porter, Freckles

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS can get away with portraying and making fun of actual, real people. Politicians, mostly. And since politicians are public figures, they have to suck it up and endure the ridicule. But comic strip cartoonists in the other venues of the daily newspaper aren’t so lucky. If they picture even supposedly anonymous persons and subject them to ridicule, those persons suddenly cease being anonymous and assume actual names and write editors complaining that they’re being persecuted. Strip cartoonists don’t make fun of policemen, f’instance, unless they want editors of subscribing newspapers to be flooded with phone calls from policemen and their relatives, all objecting to an unfavorable portrayal of cops in a strip. And sometimes, readers complain even if the comic strip is not making a joke about them: they assume that just by the appearance of their name in a comic strip, they’re being ridiculed. No cops in comics. By the same token, comic strip cartooners avoid giving actual names to any of the characters in their strips. The range of sensitivity on such matters is beyond imagining. A woman in Pittsburgh objected to Mike Peters’ Grimm drinking out of a toilet because such depictions set a bad example. She has a little dog, see, and if her dog saw what Grim was up to, well .... True story. A few weeks ago, a reader wrote in complaining about a trope in Beetle Bailey: Sarge giving Beetle a beating was not a nice thing to do when “our boys” are “over there” in Afghanistan being shot, killed and traumatized daily. (Some of “our boys” are probably traumatizing the local population. Not only do we have cases exposing such unacceptable behavior, but in a recent book, Shoot Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam by Nick Turse, we learn that “My Lai was an operation, not an aberration.” The atrocity was, apparently—and Turse has received high marks for his research—standard operating procedure. It’s shameful, but not surprising: put any number of young, inexperienced men into a daily, hourly, life-threatening situation involving an enemy population that lurks behind every bush, and those young men are likely to seek self-preservation in brutal, uncivilized ways. They, after all, are being subjected to uncivilized treatment themselves.) How,

then, is a comic strip cartoonist to escape such knee-jerk criticism? Jeff

MacNelly escaped by converting all of the characters into animals in his

panel, Pluggers. Animals don’t phone editors to complain. Pluggers are,

if we judge from the cartoon, persons who persist, often in unjustifiable ways,

in doing what they’ve always done, regardless of the march of time,

civilization, and technology. Pluggers endure but they’re old fashioned. They

don’t move forward much. And so, we are likely to laugh at them. They are the

universal butt of the joke. Looking at a week’s array of the feature that we’ve posted here, in the corner of your eye, we can see the wisdom of MacNelly’s maneuver. Starting at the upper left and then going left-to-right, then top to bottom, we see that Pluggers are not serious about exercise, that their mastery of written language is so fragile that they can’t be trusted to shop from a written list, that they hang on to possessions like automobiles well beyond the time most other citizens would have traded up, that (next tier, on the left) WalMart is big in their lives, and that they use cameras mostly to take pictures of their grandchildren, Only in the last panel, about baseball card collecting, is the Plugger safe (and then only marginally) from ridicule for his outdated preoccupation. “Real” baseball cards—the most authentic antiques—did come out of the wrapper around bubblegum. If MacNelly had used real cartoon people in Pluggers, he’d have been assaulted daily by people of the Plugger generation who resented being ridiculed for, say, their aversion to exercise, their inability to shop from a written list, their old cars, their devotion to the bargains at Walmart, and their negligent photographic skills. But no one—well, hardly anyone—among the human [sic] sapiens will complain about the silly behavior of animals. Animals are known to be silly. We can safely laugh at them. But, apparently, we cannot laugh at ourselves. Which reminds me of Amy Lago’s classic rejoinder: as comics editor at the Washington Post Writers Group, she gets complaints from readers often, and her response is just as likely to be: “If you can’t take a joke, what’re you doing on the comics page?” (Well, she thinks it; she may not actually say it.) But lots of us can’t take a joke, it seems. Therefore, it is no accident that there are so many animal strips, particularly animal strips whose stars are somewhat disagreeable (as well as anthropomorphic and therefore humanoid): in Pearls Before Swine we have Rat; can you imagine Rat as a person? What would he look like? And how many readers would take offense? But no one takes offense at a rat being a nasty personality; that’s how rats are. By the same token, in Get Fuzzy, we have Bucky; in Garfield, Garfield. In Shoe, the irascible Shoe. Only Mutts is an animal strip about agreeable animals. In superhero comic books, a typical adverse reader reaction may have been to the beatings that the bad guys were subjected to at the hands of the super-powered good guys. Not only was the match-up unfair, but the violence set a bad example. The superhero industry’s response to such (oft more imagined than actual) reader reaction was to eliminate the traditional bad guys: starting in some dimly remembered past decade, all the bad guys in superhero comics were from outer space and were as super-powered as the good guys. And to complete the transformation from violence to harmless confrontations, the superpowers involved “force fields” and “power bolts” emanating from the superguy’s open palms. No blood, no gore, no bruises even. Bad guys hit with power bolts were simply rendered inoperative. Not dead. But then— Zombies were the next logical step, and that’s why we’re up to our elbows in the walking dead. Zombies make perfect bad guys because since they’re already dead, heroes don’t actually kill them when they blast them to pieces with giant guns. Harmless faux violence.

EDITOONERY Some of the Best of the Past Couple Weeks EVER SINCE LOSING THE ELECTION last fall, the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm has been grasping at straws, trying to explain the loss. At first, you’ll recall, John Boehner (pronounced “boner”) and Mitch McConnell (pronounced “fatuous sphincter”) and their minions attempted to convince us that the GOP hadn’t lost: they’d retained control of the House, after all. Well, yes; but they lost a couple seats. And they hadn’t, despite all their hard work, gained control of the Senate (even though there were a couple of vulnerable Democrat seats). And then there was the little matter of the Presidency. Nope, no cigar, guys: you lost. Once the power brokers in the Republicon Party realized how futile it was to pretend to have won in the face of all the evidence to the contrary, they started flailing desperately about in the hope that all their expenditure of energy would attract a constituency that they’d deliberately ignored for several years. The GOP even commissioned a special report to find out what is wrong with it. Surprisingly, as humorist Will Durst reported, “they found nothing wrong with the party message; the problem is all in the delivery. No need to demonstrate more compassion, the trick is to seem more compassionate.” For far too many, party purity trumps electoral victory. Since

most editorial cartooners are liberal, they’ve been relishing the predicament

of the opposition. Partly, that’s because the GOP is the

opposition; and partly, it’s because the GOP’s dilemma is so rich with

possibilities for cartoons and the raucous laughter their ridicule arouses. Next around the clock, John Darkow offers one explanation for the GOP’s loss. The metaphor of two people occupying a four-legged costume is a classic for portraying dysfunction or resentment about the roles being played by different sensibilities. Here, the ass end of the enterprise gives voice to the Tea Baggers’ position while the Establishment makes sure we don’t misunderstand the metaphor. Next, Michael Luckovich takes the GOP-Tea Bagger relationship to the next level, showing that the Republicon Party’s electoral disadvantage is a disadvantage for the whole country. Well, at least for the government. Finally, here’s Lee Judge, who begins to isolate for the GOP the nature of its problem. The Party’s idea of personal freedom is, in fact, to deny it at every opportunity. Judge, by the way, has an intriguing book of his cartoons out. Entitled The Stuff They Wouldn’t Print (2010, Kansas City Star Books; 204 8.5x8.5-inch pages, b/w), the volume presents a selection of Judge’s cartoons that his editors wouldn’t publish—accompanied by the cartoonist’s annotations. These are presumably rough sketches, but Judge’s style is so relaxed in its final form that you’re not likely to notice that the art is unfinished. Excellent work and highly educational. In

our next visual aid, Milt Priggee continues the revelation for the

dubious benefit of the GOP. To win, the GOP must broaden its appeal, and incident thereto, it must abandon the exclusionary policies it has adopted—its extremist fixation on lowering taxes for the rich and its hostile attitude about social programs and minority voters. In short, it must begin to govern, and governing means attending to the needs of the very citizens the Party has been so determined to exclude in its pandering to a base that cares for no one but itself. Turning

aside from the hopeless preoccupations of the hapless Pachyderm, I can’t leave

the gun issue alone. It continues to attract headlines, and in our next

exhibit, we see how some of the inky-fingered brethren have reacted. The NRA, incidentally, has finally come forward with its formal proposal for safer schools—armed security. The Rambos recommend hiring professional security guards or off-duty policemen. Or teachers, who would be required to undergo exhaustive training in the use of firearms. All of these persons would undergo extensive background checks, exactly the ordeal that the NRA, speaking out of the other side of its mouth, strenuously resists for all the rest of the gun-wielding populace. The irony grates on my last remaining nerve like finger-nails scraping across the blackboard. Support

for gun control legislation is slowly eroding as we get further away from the

Newtown massacre. It is ever thus, as Al Capp knew two generations ago. With the next two cartoons, we turn, at last, away from the emotion-laden issues of gun control and the GOP’s dismal performance as a political party to visit, briefly, other matters that exercise the nation’s populace and its political cartoonists. Nick Anderson’s graphic irony at the upper right is a beaut even if the visual metaphor inherent in cartooning isn’t much exploited. Ditto Andy Singer’s commentary, which is uncomfortably close to being a practical solution to our financial woes. We

continue to explore other public concerns in the next display. Pat Oliphant gives us the most telling image of this exhibit: the predatory black birds (Oliphant’s current image for the Supreme Court) invading the privacy of the marriage bedroom, striking terror into the hearts of the defenseless couple in bed. Finally, Jeff Danziger offers a purely hilarious take on women being admitted to combat roles in the military. “Die liberal pigs” indeed. Danziger’s Coulter is every bit as articulate as the real one.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

WE’RE SUPPOSEDLY OUT OF IRAQ, but there remain 8,499 contractors in the country—of whom 2,386 are U.S. citizens. In Afghanistan, where we still have about 60,000 troops stationed, the contractors outnumber the soldiers with 110,000, of whom 34,000 are Americans. In both countries, my guess is that American companies hold the contracts and hire locals in addition to Americans. In Iraq, that’s 2,064 from the host nation, plus another 4,029 from third countries. Speaking of Afghanistan, why has it taken so long to train an army there? Or a national police force? We train whole brigades of soldiers hereabouts in less than six months. But in Afghanistan, as we’ve learned, we have an entirely different situation. Most notably, widespread near poverty. An impoverished young man can earn enough for a comfortable living for himself and his family for a year or more by enlisting for a short time in the army; after he’s accumulated money enough, he deserts. Understandably, the rate of desertion is very high. Hence, the training goes on and on.

BUT THERE’S GOOD NEWS : according to Jim Hightower’s Lowdown, only 8% of Americans now identify themselves as Tea Baggers. A declining percentage. AND THE REASON I supported the appointment of Chuck Hagel as Secretary of Defense: he has the right enemies, all people whose opinions on such matters I disagree with. Good for Chuck.

BIG BROTHER is here. Drones. Some are very large; some tiny; some can fly sideways and backwards; some can operate from eight miles up; some can hang motionless in the sky (“hover and stare,” as their spook operators say)—and all can silently surveil whatever is occurring beneath them for miles around. From Hightower’s Lowdown, February 2013.

BOOK MARQUEE Brief Reviews of Books on the Shelf and Previews of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

Icons of the American Comic Book Collected and Edited by Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith 920 7x10-inch pages, 2 volumes; some b/w illo but mostly scholarly text; Greenwood harcover, $189 (less at Amazon) IN 101 CHAPTERS OF 6-8 pages each, the book goes from Adams, Neal, to Zap Comics, mixing cartoonists and comic book characters—Carl Barks and Batgirl and Black Panther, The Killing Joke, Pogo, Mad to Maus, Richie Rich, Wertham to Watchmen. At Amazon, you can read a few pages of sample chapters. The ones I read seemed general rather than specific, historical rather than analytical (although somewhat casual about dates). Mad’s place in the history of comics and its supposed impact on American culture are adequately described, but very little is said about how its satire works. Moreover, the writer (whose name didn’t make it into the Amazon preview) clings to the notion that Mad was concocted in magazine format partly to enable publisher Bill Gaines to evade the censorship of the Comics Code Authority, which had loomed less than a year before Mad magazine’s debut—despite Gaines’ specific denial of this maneuver. I could easily launch into a tirade about how Batgirl and The Killing Joke don’t belong in the same company as Maus and Watchmen, but anyone can do that. However debatable some of the inclusions, this tome could identify the comic book “canon” that scholars have been in quest of for so long.

IF A CANON OF COMICS EXISTED, it would solve some of the problems comics scholarship presently faces according to Walter Biggins, who has been acquisitions editor at the University Press of Mississippi (UPM) for the last five years (and for a few years before that, although not by title). Biggins, with whom I worked in getting my latest book accepted for publication by UPM (it will be published next spring), left UPM last month to become senior acquisitions editor at the University of Georgia Press, and his departure prompted comics chronicler Jeet Heer to interview him about the state of comics scholarship. (The entire interview is posted at The Comics Journal, tcj.com.) After noting that “a lot of groundbreaking work was done by independent scholars not really affiliated with any academic institution,” Heer observed that in recent years, more and more comics scholarship is being committed by academics, not independent students of the medium. He asked Biggins if there still room for that sort of independent scholarship “or has the field really shifted deeply into the academy and theory?” Here’s Biggins’ response (in italics): I liken comics studies to where film studies was in the 1970s and 1980s—cool and edgy in some precincts, a trivializing affront to the ivory tower in others, and lacking cohesion in part because there wasn’t an agreed-upon framework for criticism or even a relatively agreed-upon canon. It’s like scholars, in and out of the university, are flying blind, and as a result constructing multiple versions of comics’ lineage, with some overlap but also a lot of dissension. So, for the foreseeable future, I think comics studies will feature a mix of independent obsessives and those affiliated with the academy. The independent scholars often are the ones who actually know the most about both comics and comics scholarship. I can’t tell you how often, even now, I receive proposals from a dutiful, earnest English professor about “this canonical work called Persepolis or about “Chris Ware, the one true master of the form,” or from equally earnest grad students who haven’t read— or even heard of—any comics criticism other than McCloud’s Understanding Comics. What the academy does have going for it that independent scholars largely do not (though this is improving) is rigorous standards regarding how scholarship is done, how archiving is accomplished, how citations and sources can be determined as trustworthy (or not). Regarding comics studies, there’s a certain naïveté in the academy, but among the indies there’s an equally problematic clan mentality and fandom that often confuses enthusiasm for scholarship. To change this paradigm, the territory needs to better defined. We need a canon. We need agreed-upon terminology—a Strunk & White or Chicago Manual of Style for comics criticism, if you will. And then, once we have that, we need that framework to be established in universities more prominently than it is now. In short, we need comics studies departments and graduate programs. Right now, the field, as it exists in the academy, is folded into English, sociology, history, and art history departments. Academic scholars come from all over the place, which indicates that there is enthusiasm for the discipline (that’s good!) but which also means that the studies are using a scattershot array of critical frameworks that often move at conflicting purposes and with some mutually exclusive methodologies (that’s bad!). Until there are comics studies departments established more readily in colleges, and there’s an established canon and critical methodology, the academy will need the Bill Blackbeards, Trina Robbinses, Bob Levins, and Paul Gravetts of the world. I think we’re a decade away from such programs being normalized. Even then, the indie scholars and archivists—and let’s remember that it’s largely through them that we have any original source material to work with—will often have a place in comics scholarship, simply because they are good writers who have lots of archival material (original art, interviews, newspaper collections, etc.) that would be otherwise inaccessible. But they’ll need to learn how to apply rigorous critical demands to their work and, in doing so, will debunk some of the many mythologies that have built up about comics production.

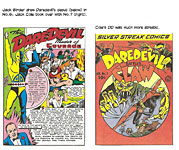

Silver Streak Archives: V olume 1, Issues 6-9, Featuring the Original Daredevil Foreword by Michael T. Gilbert 288 6.5x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardback, $59.99 Silver Streak Archives: V olume 2, Issues 10-13, Featuring the Original Daredevil Foreword by Michael T. Gilbert 288 6.5x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardback, $59.99 THE BIG REASON for reprinting Silver Streak Comics starts with No.6 and ends with No.10. The “Original” Daredevil (star of some of Lev Gleason’s comics) debuts in No.6, and in No.7, he’s written and drawn by Jack Cole, who does his last Daredevil in No.10, after which, Cole leaves Gleason and goes to Quality where he invents his stellar creation, Plastic Man. Early Jack Cole superhero stories and Daredevil—those constitute the big reason for reprinting Silver Streak Comics. But there are other somewhat less spectacular reasons for enjoying Silver Streak Nos.6-13. The SS comic book, launched in December1939 by Arthur Bernard, speaks volumes about how confused the comic book industry was in those early years; Bernard, who was apparently trying to cash in on a medium just safely launched into big money with the arrival in 1938 of Superman, seemingly didn’t know, exactly, what he was imitating. His comic book took its name from a race car; then, oddly, a character named Silver Streak shows up in No.3. The cover story star of the first issue was a giant Oriental bogieman named the Claw. Although Michael Gilbert tells us that Jack Cole was hired in 1939 to edit the comic book, it wasn’t until No.4 that he had any impact upon the product. His emergence into editorial stardom was doubtless a consequence of Gleason becoming publisher with No.3. In No.4, Cole took over the Silver Streak content, replacing the pedestrian (albeit adequate) work of Jack Binder with some flashy turns of his own, including a snappy skin-tight costume for giving Silver Streak. Binder

drew Daredevil’s debut in No.6 (as we see with the splash page in the

accompanying exhibit), but Cole took over the feature with No. 7, giving

Daredevil a spectacular workout in battle with the Claw (hinted at on the cover

to No.7, also depicted in our exhibit) and, as art director of the title,

turning the drab yellow half of DD’s costume into a brilliant red. Much better. Other confusing elements in the early issues of Silver Streak arise from the coming and going of backup characters, who show up, try out for an issue or so, then disappear when they fail to attract a vociferous readership. Lance Hale, Captain Battle, Pirate Prince (expertly done by Dick Briefer after the character’s debut with Cole), Mister Midnight, the Wasp, Spiritman, Dynamo Hill, Captain Fearless, Solar Patrol (Joe Simon’s one shot), Planet Patrol, Ace Powers, Secret Agent X-101, Dan Dearborn, Cloud Curtis, the Duke, Red Reeves, Bill Wayne “the Texas Terror” (John Wayne’s brother?), Presto Martin, Sky Wolf—some stayed for the run of the title; many dropped away after a couple issues. Dickie Dean, the Boy Inventor given lively adventures by Cole, persisted through the run and into SS’s successor, Crime Does Not Pay, but Dickie was the exception, not the rule. In addition to the pioneering artists thus far named, Fred Guardineer did some work in Silver Streak, and I think I see telltale trap-shadow signs of Jack Kirby (although Gilbert doesn’t mention him), and by the end of Volume 2, the dubious Bob Wood, killer and drunkard, was aboard. (See Opus 284 for explanation of that seeming slur.) But

the glimpses into funnybook history afforded by this pair of reprints extend

beyond the four-color pages. One of the black-and-white advertising pages

offers an insight that ought to revise our understanding of the history of the

medium. Most of the ads offer products of presumed interest to youthful

readers—collectible stamps, guitars, bicycles, radios and wrist watches, Gene

Autry holster set with two Gene Autry revolvers, movie projectors, and, with

No.7 (January 1941), the Red Ryder “Cowboy Carbine,” the soon-to-be-ubiquitous

Daisy Air Rifle. But in the same issue, we encounter a wholly unanticipated

product being advertised: The Audels Auto Guide handbook for mechanics. “Diesel engines fully treated.” Clearly, this is a product only an adult would buy. Is this merely another instance of Bernhard’s confusion about what comic books are all about? Well, yes and no. In these two volumes of reprints, we find no other ads for adult products. The auto mechanic handbook is not rerun. It’s probably a last vestige of the earliest idea comic book publishers had about their publications. I don’t own any actual antique comic books from this earliest period, but I once asked eminence gris Jerry Bails to tell me about the advertisements he saw in Action Comics No.1 and others of that vintage. Among the products advertised were razor blades. Again, a product only an adult male would be likely to buy. Advertising in early comic books also included, as we see in Silver Streak Comics, products only kids would be interested in. But products for adult consumption were present too. From the evidence, then, we may safely conclude that publishers of early comic books thought they were producing something both adults and youngsters would be interested in. Apart from advertising, other evidence supports this contention—the testimony of the periodical publishing trends of the times. The earliest comic books—before Action Comics No.1—reprinted newspaper comic strips; and comic strips were understood by newspaper publishers as entertainment for both adults and juveniles. Comic books grew out of the pulp publishing enterprise of the 1920s and 1930s; and pulp publishers aimed for adult as well as young readers. More adult than young, probably; but that simply reinforces my conviction that comic books were initially intended not just for young readers but for adults, too. For the entire family. So what happened? Superman happened.

THE HISTORY OF SUPERMAN also suggests that publishers thought of comic books as reading matter for adults. Superman was repeatedly turned down by both newspaper syndicates and by comic book publishers. Some of the histories of comics suggest that Superman was rejected because it was unbelievable. For whom? For adults. Young readers (as would be ringingly established later) would eagerly accept Superman’s outlandish abilities. But, thought the pulp publishing moguls, not adults. Syndicate officials, knowing that newspaper comic strips were intended chiefly for adult readers, rejected Superman for the same reason: it was too unbelievable for adult consumption. Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, however, was experimenting. He was in an innovative frame of mind. He was exploring new ground with his comic books. He had been in the syndication business, selling serialized illustrated fiction to newspapers, and his line of comic books might have been concocted at least in part as sales brochures for features he hoped to distribute to newspapers. That may have been why he was buying and publishing “original” material in his comic books, not reprinting newspaper comic strips. Wheeler-Nicholson was already using in his comic books material produced by Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Clearly, they would have offered him Superman at some point. Wheeler-Nicholson’s son claims (in Alter Ego No.88) that his father had agreed to buy Superman as early as the fall of 1937. Action Comics was devised as the vehicle by which Superman would be introduced to the world. Before that could happen, however, Wheeler-Nicholson ran out of money and owed his printer. His printer, Harry Donenfeld, took over Wheeler-Nicholson’s comic book line to settle the debt and plunged ahead with the Action Comics plan, including Superman as the cover feature. With that, comic books were on the cusp of becoming junk literature for juveniles. When Donenfeld learned that Action Comics was selling because kids were coughing up dimes to witness the further exploits of the Man of Steel, that was the end of comic books as “family entertainment”—entertainment for adults as well as youngsters. Donenfeld, no dummy when not in his cups, went where the marketplace told him to go: he told the producers of his comic book line to aim their stories for young readers, not adults. Donenfeld wanted those dimes. And he got them. And so did a host of his imitators. Thanks to Superman, comic books would be produced for juvenile readers for a generation. Adult themes were eschewed. The Man of Steal and destroyed the infant industry that gave him birth. Not until underground comix and the Marvel revolution of the 1960s did the four-color fantasies begin to aim for adult readership again. Part of Bernard’s confusion, then, was in persisting in a publishing plan that Superman had blasted out of existence. As late as January 1941, Bernard still thought comic books were entertainment for the whole family, adults as well as kids. The auto mechanic’s handbook advertised in Silver Streak Comics No.7 was that scheme’s last gasp, a hold-over from a now extinct era. Other hold-overs dribbled out in comic books of the early 1940s, but the paradigm had shifted. And thanks to Dark Horse, we glimpse that era everso briefly before the window closes on it—slowly, gradually, but firmly—for a generation.

FOOTNITS. Daredevil was continued by Don Rico after Cole left Gleason.

Crime Does Not Pay, Vol.3: Nos. 30-33 Foreword by Howard Chaykin 240 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 CHAYKIN’S FOREWORD is mostly appreciative blather, a fond setup for the four issues of CDNP originally published from November 1943 through May 1944. The numbering (Nos.30-33) is somewhat misleading. CDNP replaced Silver Streak in the Gleason line-up and assumed the Silver Streak numbering with No.22; so this volume reprints the 9th through the 12th issues of the most notorious comic book in American comic book history—the pioneering title that shaped the post-World War II comic book industry, yielding, eventually, the EC crime and horror books and, inevitably, the subsequent Wertham destruction of the funnybook biz. In these pages, then, we have the “testimony” that condemned an entire industry. Another in Dark Horse’s archival endeavors, the book’s table of contents is the second most important feature of the volume (the first consists of the stories): it lists the stories and the artists whenever they are known. Credits include Dick Briefer, Jack Cole, A. Kaplan, Rudy Palais, and a few others. Briefer enjoys the most frequent credit; and I think the Cole credit is wrong—the pictures attributed to him are stylistically too different from, say, his work in Silver Streak a few years before (which, even then, closely resembled his Plastic Man style). Some of the rendering herein, particularly Briefer’s, is cartoony to the point of comical. Most of it is relatively simple linework, which results in a much cleaner, clearer reproduction than more elaborate realistic drawing styles. One of the ads reproduced is for a drinking glass (“ideal for beer, highballs, and every beverage”), suggesting strenuously that Lev Gleason imagined an audience for the title that was at least partially adult—families, as with the now defunct Silver Streak. Most of the ads, however, are for products of interest primarily to young people.

Adventures Into the Unknown: Pre-code Horror Anthology, Vol. 2: Nos. 5-8 Foreword by Bruce Jones 220 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 IN THE SPIRIT OF AMERICA’S NEW ZOMBIE MARKETPLACE, Dark Horse has plunged headlong into reprinting the bizarrest remnants of yesteryear—the most notorious of the crime comics, as we’ve just seen, the pace-setting Crime Does Not Pay, and the earliest regular manifestation of horror, which came, not from EC Comics (which perfected the genre), but from American Comics Group (the fondly recalled ACG, publisher, also, of Ha Ha, Giggle, and that jolly funny animal ilk). We reviewed Volume 1 of Adventures into the Unknown in Opus 295, and Volume 2, at hand, continues in the same vein with the content of the four issues dated from June 1949 through January 1950—right up to the cusp of the EC era (which got going in earnest in the spring of 1950). As plenty of others have observed, ACG wasn’t into gore and blood as much as EC would be, but the tales have eerie and torque, and if that’s your bag, this is your book, another of them. Among the artists represented herein are Jon L. Blummer, Rudy Palais, Bob Lubbers, John Celardo and Johnny Craig—all destined for even greater things—plus a raft of unidentified ink-slingers. A continuing character emerges in No.5, the Spirit of Frankenstein, who returns in No.8 to finish the volume. Dark Horse includes the advertising pages with astonishing results—ads purport to help women reduce and seduce. Losing weight is a persistent advertising theme as are “beauty aids” (uplift bra, waist nipper, garter belt) and a Special Design “Up and Out” bra for small bust women “gives you a fuller, alluring bustline instantly—No Pads!” Dresses—“Florida Fashions”—for $2.98 each (2 for $5.85). If the ads in Silver Streak suggest an adult readership, so does this title. Or did ACG think horror was a romance genre? Probably not. Probably the publisher assumed that “horror” was not a suitable subject for young readers and supposed that this title would be picked off the racks by adults, including women. By 1949, we’re well beyond the infancy of the comic book biz, and publishers now knew what they were about and weren’t groping as Arthur Bernard probably was as late as January 1941 in Silver Streak No.7. Unknown No.8's letters column includes a bubbling approval epistle from one Nelson Bridwell, destined for a career editing comics at DC, who writes from Oklahoma City: “I am 17 and an amateur cartoonist, and it takes a really good comic to get my attention. That’s why Adventures Into the Unknown is ranked among my favorites. Did I say ‘comic’? Your magazine is in no class with most of the so-called comics. It is a new and unique idea to present age-old beliefs and superstition in picture-story form. Recently I have seen some attempts to imitate your idea [probably “ghost stories”], but none were nearly as good. Your book is truly in a class by itself!” Reproduction is uneven: some art is clearly reproduced; some, blotchy and blotted. A consequence, no doubt, of inferior source material. The more elaborately feathered and shaded art doesn’t survive the digital reconstruction as well as the simpler, outline styled drawings. And because horror stories, to be properly horrifying, had to be realistically drawn, most of this title’s content is rendered with flourishes of feathering and shading—resulting in matted patches and lost detail. But the verbal content—speech balloons and captions—appear in pristine condition, so the grisly (often campy so extreme are the dilemmas) tales herein are still entertaining.

Forbidden Worlds, Vol. 1: Nos.1-4 Introduction by Dan Nadel 216 7x10-inch pages, color; Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 CONTINUING ITS CRUSADE to corner the horror market, with this title, Dark Horse delves into “the supernatural,” eerie phenomena rather than terrifying ghouls, in four issues from July 1951 through February 1952. By this time, EC Comics was flooding the newsstands with its own horror titles (and war story books), but Forbidden’s ACG is not trying to compete in the oozing entrails game so this title is gore-free. The volume includes a table of contents page that lists all the stories, issue by issue, and, where known, the artists. Credited herewith are Al Williamson (once with Frank Frazetta inking his pencils; once with Wally Wood—both because Williamson at this stage in his career was terrified of ruining excellent pencils by inking them himself), Paul Reinman, Emil Gershwin (crisp, clean, bold linework), Henry Kiefer, Edvard Moritz, King Ward, Ogden Whitney (not as stylistically pristine as his subsequent Skyman), Charlie Sultan, and George Wihelms, to name most of them. The two Williamson-penciled stories are fascinating to observe: Frazetta follows Williamson’s pencils, but Wood takes possession of the pictures, displacing Williamson’s distinctive style with his own quirky shadowing. Reproduction is remarkably better than Dark Horse’s Unknown reprint: probably more pristine copies of the original comic books were available to shoot from. Among

the ads here is one for Motors Auto Repair Manual—“How To Fix

The Best From the Tomb Edited by Peter Normanton, the Tomb’s founding editor 192 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w plus color section; TwoMorrows paperback, $27.95 FOR SOME ACTUAL HISTORY of horror comics, we have this recapitulation, a selection of the articles from Peter Normanton’s From the Tomb, a British fanzine that started in 2000 and ran for ten years through 28 issues. The history is of the hodge-podge hit-and-miss sort: after an introductory essay on early horror comics (beginning, some say, with Avon’s one-shot Eerie anthology in January 1947; others, with the Classic Comics’ 1943 telling of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), essays focus on favorite artists (Matt Fox, Alvin Hollingsworth, Basil Wolverton, Jerry Grandenetti, Frank Frazetta, Johnny Craig, Richard Corben, Lou Cameron, Rudy Palais and a few more) and publishers (ACG, Atlas, EC, Fiction House, Harvey, Skywald, Warren, House of Hammer and others). The essays are often affectionate effusions of the typical fan sort rather than detailed, carefully researched and dated histories, but there’s plenty of meat. A 2002 interview with Al Feldstein, for example, discloses just how bitter and resentful the artist/editor is about Bill Gaines’ allegedly deliberate attempt to write Feldstein out of the history of EC and, in particular, Mad. Feldstein also has nothing good to say about Harvey Kurtzman—the other guy who gave him a career. Although Feldstein is usually credited with keeping Mad afloat and inspiring a soaring circulation, Feldstein’s Mad was little more than an endless imitation of Kurtzman’s Mad. As the interview descends into name-calling and bitterness, it emanates an increasingly bad odor. The article on Johnny Craig, however, is little more than the writer’s recitation of how he commissioned a piece of art from Craig, accompanied by a selection of Craig’s EC art—a couple covers and some interior story pages. For a publication that relishes the gruesome in comic book art, the illustrations herein are only marginally enjoyable. The selection is fine—mostly covers—but they are often reproduced too small to display much detail, even in the lavish 32-page color section. Lots of monsters and skimpily clad beauties screaming silently. Clearly, horror pulps and comics needed monsters and ghouls, but they would never have been viable periodicals without nearly barenekkidwimmin. The other thing that bothers me about this book’s treatment of illustrations is the practice of printing pictures over the gutter, which means a substantial portion of the artwork is pinched into the book’s binding rather than being on display. A stunning pencil drawing by Frazetta, f’instance, disappears into the gutter, losing altogether the subject of the illustration. Too bad. Despite these quibbles, the book as a whole is still a treat and a treasure trove of long-forgotten scraps of delightful glimpses into our horrible past.

Ditko Monsters: Gorgo! By Steve Ditko (scripts by Joe Gill); edited, designed and Introduced by Craig Yoe 240 9x11-inch pages, color; IDW/Yoe Books hardcover, $34.99 I’VE NEVER BEEN EITHER A GORGO FAN or a Ditko Fan, but this book challenges my indifference. Initially published in the early 1960s, the title displays Ditko in a Kubert phase, when his line was confident, his pictures—particularly faces—sculpted with gnarly shading, and his women delectable. Perhaps, as Yoe notes in the Introduction, Ditko was enjoying a little help from his studio-mate, fetish cartooner Eric Stanton, whose quirky passion for the curvaceous gender is an industry sensation. By No.11 of Gorgo, Ditko was also drawing Spider-Man for Stan Lee, deploying much less noodling around with shading and feathering. Ditko’s Spider-Man and Dr. Strange were both rendered with a sanitary simplicity of line that is quite different from the Gorgo books. In his Introduction, Yoe rehearses the history of the Gorgo films, observing that Gorgo is rescued from the usual run of monster flicks by the recurring participation of his mother, who shows up periodically to save him. Then Yoe digs into the comic book version, commenting on aspects of Ditko’s work. In Gorgo No.1 (1960), Ditko and writer Joe Gill followed the first Gorgo film pretty closely; thereafter, it was anyone’s game. Ditko did Nos.2 and 3 in 1960 and 1961, then skipped until No.11 in February 1963; this volume also reprints Nos.13, 14, 15, and 16, plus The Return of Gorgo No.2 from Summer 1963 and No.3, Fall 1964, by which time the Kubertesque aspects of his work have all but disappeared. Our gallery of Ditko includes mash-ups of the Kubert-like art in panels from Gorgo, plus the utterly fascinating 3-page “How Stan Lee and Steve Ditko Create Spider-Man” story from Amazing Spider-Man Annual No.1 in 1964 and another couple pages from the same title. Most of the Spider-Man pictures reveal the purity of Ditko’s later line, although when he draws Jonah Jameson, he reverts, it seems, to the kind of visage portraiture Kubert did. The 3-pager, which I didn’t know existed until I started delving into Ditko for this review, is astonishing for the accuracy of its first-page self-portrait of the artist (Ditko had an aversion to being photographed) and for Lee’s story in which Lee apparently has captured exactly the strain in the relationship between himself and Ditko: in the story, Lee seems wholly unconscious of the resentment Ditko feels, a resentment that eventually severed their relationship irreparably. But if Lee was actually that insensible, how could he write this story which reveals both his blithe obliviousness and Ditko’s brooding irritation?

The Complete Peanuts: 1985-1986 The Complete Peanuts: 1987-1988 By Charles M. Schulz; Introductions by stand-up comic Patton Oswalt and Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau Each 328 5.5x8.5-inch pages, b/w; Fantagraphics hardcovers, $28.99 WITH 38 YEARS OF PEANUTS’ nearly 50-year run between hardcovers, we’re within striking distance of the final volumes. At two years of reprints per volume, only six volumes (or three years of Fantapublishing) remain. For the 1985-86 volume, Oswalt’s Introduction is mostly a fond recollection of his earliest experience of the strip, citing Schulz’s Introduction to Bill Watterson’s The Essential Calvin and Hobbes, but he also points out that Snoopy’s “world famous attorney” makes his debut in this collection, which also includes Snoopy with a mohawk, killer bees, and Halley’s Comet. The gang goes to “rain camp” and “survival camp,” and the World War I flying ace comes down with the flu, Charlie Brown poses for a swimsuit calendar, Peppermint Patty gets a crabby tutor—and Spike visits with his cactus. The 1987-88 tome’s back cover blurb advises that this volume includes Charlie Brown’s attempt at flirting that sends him to the school nurse, and Linus being thwarted in his wooing of “Lydia” of the many names; Snoopy goes to the hospital for hockey-related knee injury, Sally writes a school play but confuses Gabriel with Geronimo, Snoopy writes a “kiss and tell” book (after kissing Lucy), Peppermint Patty complains of a headache and a simultaneous stomach ache (claiming her body is double-teaming her), and Schulz abandons the four-panel format and resorts to three—and sometimes (gasp) two panels and, at least once, one strip-wide panel! In his Introduction, Trudeau views Schulz’s achievement from a fellow professional’s perspective. Peanuts, he says, is “filled with a uniquely American sense of optimism. ... But the pain of sustaining that hope showed everywhere. ... His strip vibrated with fifties’ alienation, making it, I always thought, the first Beat strip.”

From the Files of Mike Hammer: The Complete Dailies and Sundays By Mickey Spillane and Ed Robbins; edited and introduced by Max Allan Collins 160 9x11-inch pages, b/w and color Sundays; Hermes Press hardcover, $49.99 THE NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIP version of Spillane’s tough guy private investigator Mike Hammer ran for less than a year: dailies, May 13, 1953 through March 20, 1954; Sundays, April 26, 1953 through March 14, 1954—and it’s all here, between the covers of a single volume. Max Collins is such a dedicated and life-long Spillane fan (in 2008, he completed a Mike Hammer novel, The Goliath Bone, one of several that Spillane left unfinished when he died in 2006) that he wrote two introductions to this book: the first, about his personal involvement with Spillane; the second, a review of Spillane’s career and stature as a detective novel writer. (Collins also wrote in 1984 One Lonely Knight: Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, with James L. Traylor.) The comic strip preserves the essential Mike Hammer, notorious for his callous treatment of the women he meets during his adventures and for beating up the men. The character, Spillane told Collins, evolved from a comic strip hero he developed, Mike Danger (the second version of a private eye that Spillane toyed with during the early 1940s). Unsuccessful at selling the strip into syndication, Spillane converted Danger to Hammer and his adventures into straight prose with his first novel, I, the Jury, published in 1947, but it was the paperback edition in 1948 that made both the character and his creator famous. At the time the comic strip Hammer debuted, Spillane said the character was finally appearing in the medium for which he was intended. After becoming a Jehovah’s Witness in 1952, Spillane cut back on sex and violence in his books, but by then, he’d already written the first six Mike Hammer books, and they were so popular that he could, in effect, live off the proceeds without writing another book. (And he almost did: his next novel, The Deep, a non-Hammer vehicle, wasn’t published until 1961; another Hammer book, The Girl Hunters, in 1962.) The

artist on the strip, Ed Robbins, was a workhorse in the early years of

comic books. He worked in a succession of comic art shops—Lloyd Jacquet’s

(1940-42), Beck-Costanza (1943-1953), Simon-Kirby (1955). The work he did in

the shops, drawing mostly but some writing, was published by Centaur, MLJ,

Marvel, Fawcett, Prize, Dell, Western, and others. In the pre-war years,

Robbins was drawing for Jerry Iger’s comic art shop, Funnies, Inc., while

Spillane was writing comic book stories for the shop. Spillane clearly liked

Robbins’ work, and it’s easy to see why: he renders Spillane’s snarly tough guy

in a rough-hewn version of Alex Raymond’s stylish fashion plate art in Rip

Kirby. Robbins’ manner is thoroughly accomplished, deploying solid blacks and shadowing with panache, although he overworks feathering and shading just a trifle, imparting to the final product a rougher appearance than Raymond’s work. Spillane either wrote or plotted most of the strip’s stories; Robbins collaborated in the final scripts on some of the adventures (perhaps doing most of a couple). The daily strips, published four to a page, are crisp reproductions taken from syndicate proofs; the Sundays, one tabloid format to a page, Hermes Press painstakingly rebuilt from newspaper clippings, often constructing the vertical format from half-page horizontal versions. Both the dailies and the Sundays had to be “repaired” because they’d aged, the paper turning yellow or brown, and the Sunday colors faded. The final product is admirable in most respects. The comic strip wasn’t widely distributed due, doubtless, to Spillane’s loyalty to Jerry Iger: Spillane could have gone with a big-time syndicate like King Features but instead went with Iger’s Phoenix Features, a bush-league operation without the staff to do much selling to newspapers. In various sections of the volume, evidences of Mike Hammer in popular culture—chiefly in movies and tv versions—are reproduced. Altogether, a tidy package.

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets