|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus

286 (December

5, 2011). Yes, it’s still the Year of the Rabbit, as you can see from the

accompanying visual aid, which signals our having taken the pledge to Respect

the Bird. Respect the Bird was started just a year ago when Doug Matthews in Mendham, New Jersey, posted a rant on Allrecipes.com: “The calendar seems to be going by at a frightening pace,” he wrote, “and holidays are getting blended into each other like ingredients in a smoothie. Thanksgiving is a great holiday. It’s a truly American holiday. It combines food, football and drunken relatives we actually look forward to seeing once a year.” To Respect the Bird means to preserve Thanksgiving, to prevent inroads being constructed into its borders. People who Respect the Bird celebrate Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday in November and don’t start celebrating Christmas—or the early bird Christmas shopping obsession—until Thanksgiving is entirely over. And here at Rancid Raves, as you can tell, we’ve gone completely overboard in Respecting the Bird because we’re still celebrating the movement even though the calendar has moved on, inexorably, leaving Thanksgiving well behind. The calendar has moved, but we have not. Yet. We have, however, assembled this time one of the larger feasts of comics news and reviews. We have a long segment on Occupying because at least two cartoonists have become embroiled in it. We come to the defense of Herge on the eve of the debut of Spielberg’s Tintin movie in this country. Other lengthy articles are prompted by editoonist Mike Keefe’s unexpected retirement at the Denver Post and Bil Keane’s death. And we start our anyule Christmas shopping guide with the Spouse List (Part One) reviewing 13 books, plus reviews of ten funnybooks of note and appreciations of a dozen or so editorial cartoons culled from the offerings of October. What with the length of this posting, we thought it propitious to point out the way we have devised to shorten your reading experience, should you so desire. Departmentalization. The departments into which we divide each Opus are intended to make it easy for you to find whatever you’re interested in and avoid the rest. If editorial cartoons are your passion, you can scroll past all the newsy bits and get right away to the Editoonery Department. If obits are your thing, you can skip everything by scrolling down to Passin’ Through. And for those who want to avoid my political harangues, you can stop reading when you get to the Spreading Punditry (conveniently located in the caboose so you don’t have to encounter any of it as you browse the rest of the Opus, which is conveniently located everywhere else except at the end). Well, you get the idea. The ensuing list that prefaces our every offering tells you what’s on hand so that you can, if you want to avoid topics that bore you, skip all of those and go immediately to whatever interests you the most. Here, then, is what’s here, in order by department—:

NOUS R US Short Notices Australian Cartoonist of the Year Bud Plant All Online Harvey Pekar Memorial

Occupying the World Guy Fawkes Cartooning Journalist Arrested Profession Protests Frank Miller Unloads Occupy Achievement Who Are the One Percent?

Bob Layton’s Legitimate Snit Jeff Kinney’s Millions Stan Lee Again Signe Wilkinson’s New Strip Spiegelman’s Maus Some More

MIKE KEEFE RETIRES John Sherffius Quits

Asterix’s Albert Uderzo Retires A Little

The New Peanuts Comic Book The Internet: Savior?

Is Herge a Moral Degenerate? No. The Crimes He’s Accused Of Explained

The Happy Harv on Video

EDITOONERY The Running of the Panderers: Cartoons of the Last Month Republican Prez Candidates Joe Paterno

THE SPOUSE LIST: PART ONE Reviewing Books Your Spouse Can Put Under the Tree for You Pogo: Through the Wild Blue Yonder Caniff: A Visual Biography It Was the War of the Trenches Complete Little Orphan Annie, 1936-38 100 Sexiest Women of Comics Good Girl Art by Ron Goulart The Pin-Up Art of Humorama Not Just Another Pretty Face: The Confessions and Confections of a Girlie Cartoonist

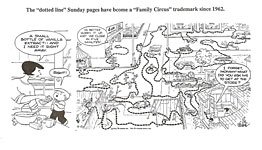

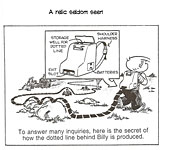

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL News and Gossip Exemplary Strips from the Last Few Months Dennis and Pearls Cross Over

BOOK MARQUEE 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die Code Word: Geronimo Joe Palooka MMA America’s Most Visible (and Vocal) Comic Character

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Liar’s Kiss, Graphic Novel

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Short reviews of Catwoman No. 3, Wolverine and the X-Men No.1, John Byrne’s Cold War No.1, Neal Adams’ Batman Odyssey No.1, Aquaman No.1; The Kents, No.1, Shade No.1, Jonny Double No.1 (graphic novelish) Who Is Jake Ellis ends; ditto The Last of the Innocent

PASSIN’ THROUGH Bil Keane Alvin Schwartz Les Daniels

ONWARD THE SPREADING PUNDITRY More of the Happy Harv’s Political Sprew

Harv’s 24-Hour Comic: If you’re looking for this because a Facebook note sent you here, you should go, instead, to Harv’s Hindsight, where the whole enchilada is posted.

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits ALLAN GARDNER AT DAILYCARTOONIST reports: “Good news for those of us watching print media struggle to gain sufficient advertising revenue as they transition to digital. The Atlantic magazine’s online advertising revenue has overtaken its print revenue for the first time.” ... Editor & Publisher reports that the Chicago Tribune has increased its page count by 40 full pages per week: “We’ve added depth, dimension and range to our news report to serve you better,” the paper’s promo said, “—we’ve strengthened the newspaper for readers who love the printed newspaper and are serious about their news.” No word, yet, on whether circulation or advertising has increased as a result. ... If you’ve been wondering what Boondocks’ Aaron McGruder has been up to lately, wonder no longer: he’s co-writer on George Lucas’ only non-Star Wars movie in 18 years, “Red Tails,” about the exploits of the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, the African American fighter pilots who battled Nazis during World War II. ... A lost Walt Disney cartoon, discovered in a British film archive, will be auctioned in Los Angeles on December 14, reported Mike Collett-White at Reuters; "Hungry Hobos" is one of 26 episodes featuring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a character created by Disney and Ub Iwerks in 1927 for Universal Studios before they created Mickey Mouse. ... In Paris, the office of the satiric weekly Charlie Hebdo was fired-bombed after the newspaper “invited” the Prophet Muhammad to be guest editor and published a caricature of him on its front page. Muslim leaders and politicians on all sides condemned the bombing, and the paper’s editor vowed that the next issue would come out on schedule even if they had to produce it with pencils on individual sheets of paper. Austrialian

illustrator and cartoonist Anton Emdin took home two awards, including

the Gold Stanley for Cartoonist of the Year, from the Australian Cartoonists

Association’s annual Stanley Awards celebration, November 11-12; this year, in

Sydney. The other award was for Best Illustrator. Emdin is the only Aussie to

receive award-recognition from the U.S.’s National Cartoonists Society: last

May in Boston, he received the Reuben division award for magazine

illustration. Bud Plant is going all-out online. Citing “increases in paper, printing and postage costs paired with declining returns on catalog-based sales,” he explained in the last issue of Bud’s Art Books catalog, “we’re obliged to make some changes in order to survive.” Henceforth, the “catalog” will be online only (at BudsArtBooks.com); no print version. In lieu of the printed catalog, an e-mail newsletter is available; it will list new titles, specials, and offer links to download periodic mini-catalogs “and other items of interest.” Orders for books can be placed online or by phone, as has been the practice for some years. Only Clevelanders would decide that American Splendor’s Harvey Pekar deserves a memorial in the city and only Clevelanders would successfully raise $30,000 to fund the project. The memorial will be in the city library but it’s not exactly a monumental statue: instead, a functional desk that will be installed and stocked with paper and pencils, providing a place where people can sit and write or draw comics, reported Pat Gallbincea at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Mounted on the desk will be a sculpted bronze comic book page, with Pekar himself stepping out from a panel.” The tribute will be located on the library's second floor, where Pekar liked to work. "Harvey was here all the time," said Carole Wallencheck, a reference associate at the library. "It was his favorite place to go.” And he’d probably get a kick out of the image. And the fuss. And the fund-raising. The Avengers made the cover story of Entertainment Weekly’s October 7 issue. This’s scarcely the first time comic book superheroes have been on EW’s cover. They’ve been there so frequently of late that we may, at last, breathe easily: comics have now been roundly accepted as legitimate manifestations of the popular culture. Juvenile junk lit no more. (Unless you assume, as many misguided souls do, that popular culture is junk culture. Then we have to start over.) The director Julie Taymor, a key creator of the Broadway musical “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark,” is suing the producers of that $75 million show, claiming that they are profiting from her creative contributions without compensating her. The lawsuit seeks at least $1 million from the producers, as well as future royalty payments. According to Patrick Healy at the New York Times, “Taymor, the Tony Award-winning director of ‘The Lion King’ and other musicals and films, has been wrangling with the producers over money and artistic credit ever since they fired her as the director of ‘Spider-Man’ in March. The dismissal shocked Taymor, her associates and friends said in the spring, adding that she was especially galled that the producers continued to use much of her staging and script contributions, even after a much-ballyhooed overhaul of the musical in April and May.”

OCCUPYING THE WORLD Everybody’s Doing It—Even Guy Fawkes A PERSISTENT IMAGE OFT SEEN among the Occupy milieu these days is a mask depicting a sallow, smirking, moustached alleged likeness of Guy Fawkes, a nearly legendary British failed revolutionary who plotted to blow up Parliament some four centuries ago. The mask was initially created by David Lloyd for Alan Moore’s 1982 graphic novel, V for Vendetta, whose protagonist seeks to destroy the government. Over the Guy Fawkes Day weekend— "Remember, remember, the Fifth of November: the gunpowder treason and plot"—Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs asked Lloyd for his thoughts on the mass appropriation of his mask: "As far as that mask is concerned, well, I'm happy it's being used as a multi-purpose banner of protest. It's like [Alberto Korda's] Che Guevara image on t-shirts and such that was used so often in the past as a symbol of revolutionary spirit—the difference being that while Che represented a specific political movement, the mask of V does not: it's neutral. It just represents opposition to any perceived tyranny, which is why it fits easily into being Everyman's tool of protest against oppression rather than being a calling card for a particular group." The man behind the mask said the Occupy Movement reminds him of [Paddy Chayevsky's 1976 satire] “Network,” in which the disillusioned newsman cries out: “I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take this anymore!” As for Alan Moore, he was smitten; as he told Tom Lamont at the guardian.co.uk:"I suppose when I was writing V for Vendetta I would in my secret heart of hearts have thought: wouldn't it be great if these ideas actually made an impact? So when you start to see that idle fantasy intrude on the regular world—it's peculiar. It feels like a character I created 30 years ago has somehow escaped the realm of fiction."

Cartooning Journalist’s Rights Violated Daryl Cagle, editorial cartoonist at cagle.msnbc.com and syndicator, through Cagle Cartoons, of the work of editorial cartoonists worldwide, has a daughter, Susie, also a cartoonist—and a journalist—who was doing cartoon reportage on Occupy Oakland for AlterNet when she and several others were arrested on November 2. Susie Cagle, despite presenting her journalist credentials, was hauled off to jail where she spent the next 15 hours. “The arresting officer knew I was press,” she said to Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs; “when he came up to me and saw my AlterNet press pass—which is bright pink-orange, like coral—he even said he knew my comics.” No matter; off to jail. When she was released, her personal effects were not, she told Laura Hudson at comicsalliance.com: “No one had keys, wallets, cell phones—so we couldn’t get into our houses.” After a day’s wait, she was able to collect her belongings, but she was charged with “failing to leave the scene of a riot.” Ironically, she was leaving when she was arrested. A week earlier, she had been tear-gassed. One of the reasons she went to cover the event was her conviction that the usual news media were not being comprehensive enough in their coverage (i.e., they were biased in favor of visuals of seedy-looking hippie-types in funny hats rather than information about what the protestors wanted). Moreover, the Oakland police department was establishing itself as unnecessarily aggressive force. As she experienced and witnessed the rude and pushy (not to say brutal) behavior of the police cracking down on protestors, she cranked up her reportorial aspirations: first, she decided to do an extensive piece, prose and pictures, on the Oakland adventure, offering it to the news organization Truthout; but by the time Hudson interviewed her on November 8, she’d decided to go to GOOD magazine. Meanwhile, she hopes the charges against her will be dropped, she said to Hudson. “I guess right now my main concern is that there were some very explicit threats about anyone returning to Occupy, and that if we were arrested on the same charge again that it would be a felony and that we would be held until a court date. They were clearly trying to intimidate. It's kind of scare-mongering.” And she’s understandably concerned: “I don't have money for bail. I don't really want to go back to jail again, but I also think that all of this makes me so much angrier and more determined to do this story because I feel like they tried to shut me up, and I can't in good conscience walk away under those circumstances. I feel like this is just getting started.” She hopes for an end to the violence, but more than that, “better news coverage from other journalists who spend as much time here and talk to people as much as I do. There are a lot of people who pop in for a minute and pop out, and then do a whole piece that doesn't really understand what's going on. It's a very complicated situation and I think it requires that sort of long view that news doesn't really have patience for these days.”

Cartoonists Rights Network Files Protest Acting on behalf of the Cartoonists Rights Network International, Drew Rougier-Chapman wrote to Nancy E. O’Malley, District Attorney, Alameda County (Oakland) with a Request to Drop Charge Against Journalist Susie Cagle; to wit—: Dear District Attorney O’Malley, Cartoonists Rights Network International is a free speech and human rights organization that looks after the free speech rights of cartoonists all over the world. I would like to bring to your attention that on November 3rd Oakland Police Officer D. Bruce unconstitutionally arrested and detained a journalist. As you are well aware, journalists have a constitutional right to cover important public events without being treated as criminals. Editorial cartoonist and reporter Susie Cagle was covering the Occupy Oakland movement in her capacity as a journalist at the time of her arrest. When the protests began, and many days before her arrest, Ms. Cagle applied for an Oakland Police Department (OPD) press badge, which has since been granted by the Oakland Police Department. While waiting for the OPD to issue an OPD press badge, Ms. Cagle received a press badge from her media employer, AlterNet. Ms. Cagle was wearing and clearly displaying her media issued press badge and told her arresting officer that she is a journalist. Photographs of Ms. Cagle being arrested clearly show her press badge. Her status as a journalist at the time of the arrest was even acknowledged in the presence of the arresting officer by another police officer who is familiar with her work. Furthermore, Ms. Cagle told her arresting officer that she had an appointment later that very day with the Oakland Police Department Public Information Officer (PIO) to finalize her paperwork. Instead of contacting either the PIO or AlterNet to verify Ms. Cagle’s status as a journalist, as Ms. Cagle requested, the arresting officer taunted the handcuffed journalist, telling her, “You’d better call her and tell her you’re going to be late.” To date a charge of failure to leave the scene of a riot is still pending against this journalist. We call on your office and the Oakland Police Department to review Ms. Cagle’s case, immediately drop the charge against this journalist, and enforce a new policy of noninterference towards the constitutionally protected activities of journalists. Since the actions of the OPD that evening equate to an extrajudicial suspension of a journalist’s First Amendment rights and a dangerous precedent if allowed to stand unchallenged, our office has no option but to consider bringing suit against the Oakland Police Department if the criminal charge against Ms. Cagle (Citation Number 0308317) is not dropped. We would like to note that in the twenty years our office has endeavored to protect the human rights and free speech rights of editorial cartoonists around the world, this is the first time we have felt compelled to write such a letter to American officers of the law, individuals who have sworn to uphold the Constitution. Please bear in mind that a journalist’s constitutional rights and responsibilities to cover important social events such as the Occupy Oakland protest do not begin when the PIO gets around to issuing a OPD press badge. Denying journalists timely access to important social events is commonplace in extralegal regimes like Zimbabwe, not in the United States of America. We would very much appreciate a response to this letter so we may communicate with the other free speech and human rights organizations that we are cooperating with on this matter.

R&R Footnit: Susie is not alone. During the sweeping up of Occupy Wall Street in New York, more than two dozen journalists were arrested. Many of them were credentialed journalists —including reporters from Vanity Fair and the Associated Press—but more than a few were likely freelance Internet bloggers whose claim to be journalists is still open to disputation. As of this writing (December 5), the charges against Susie Cagle have not been dropped: she is to be arraigned later this week.

Anger at Anarchy Occupiers inspired Frank Miller into a notable outburst, but I doubt he is making any friends with the screed he posted at FrankMillerInk.com on posted November 7. Here it is, all of it, dripping with sarcastic venom: Everybody’s been too damn polite about this nonsense: The “Occupy” movement, whether displaying itself on Wall Street or in the streets of Oakland (which has, with unspeakable cowardice, embraced it) is anything but an exercise of our blessed First Amendment. “Occupy” is nothing but a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists, an unruly mob, fed by Woodstock-era nostalgia and putrid false righteousness. These clowns can do nothing but harm America. “Occupy” is nothing short of a clumsy, poorly-expressed attempt at anarchy, to the extent that the “movement” – HAH! some “movement,” except if the word “bowel” is attached—is anything more than an ugly fashion statement by a bunch of iPhone-, iPad-wielding spoiled brats who should stop getting in the way of working people and find jobs for themselves. This is no popular uprising. This is garbage. And goodness knows they’re spewing their garbage – both politically and physically – every which way they can find. Wake up, pond scum. America is at war against a ruthless enemy. Maybe, between bouts of self-pity and all the other tasty tidbits of narcissism you’ve been served up in your sheltered, comfy little worlds, you’ve heard terms like al Qaeda and Islamicism. And this enemy of mine — not of yours, apparently— must be getting a dark chuckle, if not an outright horselaugh, out of your vain, childish, self-destructive spectacle. In the name of decency, go home to your parents, you losers. Go back to your mommas’ basements and play with your Lords Of Warcraft. Or better yet, enlist for the real thing. Maybe our military could whip some of you into shape. They might not let you babies keep your iPhones, though. Try to soldier on. Schmucks. FM

SELDOM, IF EVER, has your Rancid Raves Reporter read anything the equal of this for freeform, untrammeled, bellicose yowling. “The real thing,” Frank? Would that be the military that you were lucky was no longer drafting the youth of the nation when you came of age—so you didn’t have to serve; and, as far as I know, didn’t? As an unrepentant admirer of Miller’s work, I appreciate his talent and his achievements. Even his latest, Holy Terror (which we reviewed in Opus 285), has its nastiness tempered by Miller’s superior skill at his craft and art. But there—and here—he’s let his fear and anger at the abhorrent predations of al Qaeda unhorse his reason. Name-calling will accomplish nothing, Frank—no matter how extreme the vocabulary. I agree that the Occupy minions may reek of “Woodstock-era nostalgia” and include a fair number of anti-authoritarians, campus rebels, and probably some loutish loafers who say they can’t find a job without having looked very hard. But however malformed the Occupy ranks may be, the notion that joining the U.S. Army to fight al Qaeda is the best way of protesting the abuses for which the notorious One Percent is now known is about as misguided as many, yourself included, see the Occupiers as being. I applaud their noise and scrawled signage. Someone had to shriek in rage and frustration at the imperious millionaires who, operating well out of sight (and apparently out of reach), keep us all docile with credit cards and then sock us with higher fees, gamble at high finance games no one understands, and bankrupt a financial system through sheer unregulated greed—er, I mean unregulated capitalism. Same thing. But joining the military may not be a bad idea—although for reasons you, Frank, having not served, cannot know. A recent Pew Research Center report found that, increasingly, the number of Americans who have served in the military or who have a family member who has served is steadily decreasing. Over three-quarters of Americans over the age of 50 had an immediate family member who served; but only a third of those 18-29 years of age have that experience. Some hand-wringing academics (a newspaper account reveals) are worried about this: the fewer connections between the military and the rest of society, the less well-informed are decisions about going to war because conflicts and the people who fight them are not part of most people’s everyday lives. That’s a stretch, maybe: I don’t think ordinary service as a grunt in the army necessarily supplies a person with the expertise to make informed decisions about going to war. But there are other hazards inherent in our present military configuration. The practice of out-sourcing many of the functions that the military once performed—everything from food preparation and service to guard duty and over-all security—should ring another alarm bell: if all military operations are done by hired guns (to which circumstance we are frighteningly close in our latest extra-national belligerence), then no one’s children are involuntarily put in harm’s way. It is then much easier for Congress to vote for war—and a president to send troops overseas to fight—if all those shooting and being shot at have chosen that way of life. That’s what those guys signed up for, after all; and they’re unhappy if they’re not firing off guns and rockets. War makes them happy. If we re-instituted the draft that was shut down in 1973 (when Frank Miller was 16 years old), we’d have enough personnel in uniform to do the jobs now being done by mercenaries, and we’d be less eager to go adventuring. The draft, or, rather, the near universal military service that it engendered, did something else for the nation: it was a great unifier. Everyone who served had a more-or-less common experience for one extended period of their lives. Some of that experience was nothing to write home about; but some of it was. In any event, we all emerged with a somewhat heightened sense of the brother/sisterhood of humanity. And an awareness of a national bond that goes beyond the infantile chest-thumping patriotism of cable-tv gasbags. Not a bad thing.

The Occupy Achievement After the evacuation of Occupy Los Angeles, sanitation workers wearing surgical masks hauled away 25 tons of debris from the lawns around City Hall. Those who think that’s about all the protest has accomplished need to think again. The Hightower Lowdown begins its report on Occupy with this: “Americans who flew bombing missions in World War II had a saying: ‘You know you’re on target when you start getting a lot of flak.’ The protesters in today’s Occupy movement must really be on target, then, because—boy!—they’re enduring an unrelenting barrage of rhetorical flak from political and media defenders of America’s plutocracy.” Rush Limbaugh weighed in with a “gusher of vitriol” against “anarchists” and “union thugs” before reaching this conclusion: “There’s no doubt in my mind that the White House is behind this. Obama is setting up riots.” Mitt Romney called it “class warfare.” Glenn Beck warned that “these guys ... will come for you and drag you into the streets and kill you. ... They are Marxist radicals. ... They will kill everybody.” The ever-astute Ann Coulter brands the movement as “the flea party ... wingless, bloodsucking, and parasitic.” One of the criticisms of the movement is that it has no agenda, no target, no list of specific demands that can be acted upon. Publisher James Israel at Humor Times writes: “Sure it’s messy. Reading the creative handmade signs, the list of grievances is long and varied, from unfairly burdensome student loan debt to environmental degradation, Wall Street corruption to lack of affordable health care. But they are all valid concerns, and they all have a common root. And that root is the lack of real representation for the common citizen in our government. Instead of representing us, our elected officials do the bidding of the moneyed interests who fund their campaigns.” John Hightower (another flaming liberal—whom I often applaud, as I do here) agrees: “the so-called ‘unfocused’ young instigators of the Occupy movement have forced the establishment media, politicians, and Wall Street itself to take notice that masses of Americans are deeply pissed off. ... For now, protest itself is the focus, and that’s enough. While the protesters do pull from a very full grab bag of particular outrages—corporate personhood, the contamination of our food supply, eliminating collective bargaining rights, the Koch brothers, Big Oil, student loan ripoffs, government-for-sale, permanent war, downsizing and offshoring middle-class jobs, gutting health plans and pensions, etc.—practically all come down to the domination and abuse of America’s many by its evermore-privileged few.” At the Washington Post, columnist Eugene Robinson sees somewhat the same unifying element. Quoted in The Week, Robinson sees Occupy’s central idea, and a powerful one at that—“that our financial system has been warped to serve the interests of a privileged few at the expense of everyone else.” To be more specific, the One Percent who control much of the nation’s wealth have rigged the game, using campaign contributions to buy tax loopholes and relaxed regulation from Washington, and awarding themselves monstrous bonuses while laying off vast armies of the middle class. The protesters may not have supplied a point-by-point political agenda to redress that unfairness. “But they’ve done something more important”: they’ve gotten the One Percent vs. 99 percent idea “into people’s heads.” Thanks to the Occupiers, adds David Car in the New York Times, the 2012 Election may well be fought over the issue of economic fairness. If so, those who slept in parks, sat through endless “general assembly” meetings, and got roughed up by cops will know that “though their tents are gone, their fooprint remains.” And who knows how that might come out? Hightower attempts a prediction: “Despite feverish attempts by Loyal Defenders of the Plutocratic Order to mock, demonize, and otherwise make ordinary Americans fear, despise, and reject the Occupy movement, quite the opposite is occurring. An October National Journal poll found that 59 percent of Americans agree with what the protesters are saying and doing. That includes 56 percent of the white working class, a group that Limbaugh, Fox, the Kochs and other corporatists always target to foment cultural resentment, which they then twist into political energy for whatever game the moneyed class is running. Class warfare? You bet.

Fitnaught: In the midst of the Occupiers, altie cartoonist Matt Bors sees an opening for comics journalists: “News outlets are beginning to realize that comics journalism is a serious form of reporting,” Bors told ComicRiffs, “and it’s particularly helpful with a movement like Occupy.”As a syndicated editorial cartoonist, Bors has been on the scene at Occupy Portland, recording the city’s protest play-by-play, Michael Cavna observed, and as the comics journalism editor at the website Cartoon Movement, he has been coordinating the cartoon contributions of such visual journalists as Stephanie McMillan (DC and elsewhere), Shannon Wheeler (New York), Sharon Rozensweig (Chicago) and Susie Cagle— who have drawn from the encampments amid skirmishes and, sometimes, official evictions.

And Who Are the One Percent? The poster boys of the One Percent are bailed-out banksters and securities traders, hedge-fund managers and other plutocrats from the world of finance. But they represent only about 14 percent of the country’s richest taxpayers, reports The Week (November 4). According to the Internal Revenue Service, one in six of the One Percent is in medicine; one in twelve is a lawyer. “The select club of the top One Percent includes more information-technology specialists and engineers than it does entrepreneurs, and more scientists and professors than celebrities from the arts, sports, and media. Not incidentally, more than half of the U.S. senators and members of the House are among the One Percent.”

AN INTERIM MOTS & QUOTES “Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for profit, honor or private interest of any one man, family or class of men.”—John Adams, Thoughts on Government, 1776 “The world is full of people whose notion of a satisfactory future is, in fact, a return to the idealized past.”—Robertson Davies “Work like you don’t need the money. Love like you’ve never been hurt. Dance like nobody’s watching.”—Satchel Paige The GOP jobs plan, saith Michael Hiltzik in the Los Angeles Times, is a package of “shibboleths and ideological dog whistles” designed to “eviscerate” environmental regulations and protect corporate profits. “Ideological dog whistles”—I like that.

CORPORATION VS. ART Rich Johnston at bleedingcoolcom tells the tale: Bob Layton, apprentice to Wally Wood, writer, penciller, and inker for Marvel and DC, as well as a senior figure and creator at Valiant, is especially remembered for his work with David Michelinie on Iron Man. And the pair had reunited to work on the character on a mini-series Iron Man Forever. Not that Layton recognizes the final version. He writes on Facebook (quoted herewith in full): Speaking of Marvel, today, I finished the last page on the fourth and final issue of my Iron Man Forever mini-series. Sad to say, this will be my last assignment for Marvel Comics. Not that I hate them, or think that it’s a horrible place, but it's simply not the same Marvel I enjoyed working for during most of my career. It's clear to me that it's time to move on. To clarify my last statement, my decision is more about individual expression and to not become a contributor to "units sold.” The pervasive corporate atmosphere felt like the Number One goal was to crank out grist for the stockholder mill. In other words, it seemed to me that pumping out endless, poorly conceived mini-series to make sales figures has become that driving force at Marvel/Mouse. To confess, in no way, shape or form does this last Iron Man mini-series resemble what David Michelinie and I had intended it to be. Christ, we went through two editorial teams and it took over a year just to get the four measly issues to be the mess that it currently is. The story was edited and approved by a faceless committee, then run past the sales department for its approval. The sales department? Really? Well, my primary concern as a storyteller is not to assure that the Disney corporation makes its quarterly projections. More power to them, but that’s not why I got into the comic field. As much as I love Iron Man (and all of my fans worldwide), I feel it is impossible to do the kind of stories you expect from me in the current situation. Edward James Olmos recently gave me some sage advice over dinner. When describing my frustration over the situation at Marvel, he leaned over and said: "What's one more friggin' Iron Man mini-series going to contribute to your 35-year legacy?" And … I realized that he was right. Naturally. Remember folks, Edward James Olmos is always right…

FAILED CARTOONIST BANKS MILLIONS The sixth book in Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid series, Cabin Fever, was published November 15 with a first printing of more than 6 million copies, making it the biggest release of the year in both kids' and adult books, according to Publishers Weekly. Kinney has been named one of Time magazine's 100 "most influential people in the world," and two movies based on his books have grossed millions of dollars. “Kinney is one of the best-selling authors in America,” reports Karen MacPherson at Scripps Howard News Service. More than 50 million copies of his Wimpy Kid diaries are in print in the United States and Canada. The series has been translated into 35 languages. Despite all the ballyhoo and jingling cash registers, Kinney still considers himself a "failed cartoonist." "I'm an author whose strength is in gag-writing," Kinney said. "I recently went to speak at the National Cartoonists Society, and I think the line is clearly drawn between what they do and what I do." At the University of Maryland, Kinney created a comic strip called Igdoof that he hoped would catapult him into cartooning stardom; “he even changed his major from computer science to criminal justice because he thought he would have more time to draw,” MacPherson said. But when his efforts to sell Igdoof failed magnificently, Kinney turned away from his drawingboard to his computer screen and became a well-regarded website developer. “Among his creations is the popular website Poptropica.com, which was named one of Time magazines' 50 best websites.” Kinney told MacPherson that he expects to write 7 - 10 Wimpy books, so there is at least one more brewing somewhere in Kinney’s stick-figured mind. Maybe more than one.

ANOTHER COMEBACK AGAIN Stan Lee, 88, is at it again. Alex Dobuzinskis at Reuters reports that POW! Entertainment, Lee’s current company, is invading the Internet hoping to make money at it with a YouTube project called “Stan Lee’s World of Heroes,” which will feature short, live-action videos and animation. "The Internet is so much bigger,” Lee said in a phone interview, “and it's so all encompassing and everybody is involved in it. Years ago, it was just getting started. This is the perfect time for us to dive in with both feet." Of the characters he is planning to unleash, Lee said, “there will be some with super power, and there will be some that are just good stories of people doing good things.” The time is ripe for superheroes on the Web, Lee thinks. "I am hoping everything we're doing at POW! will be as good or even better than what I did at Marvel because I'm more experienced now," he said. "I know more now than I knew then." Us old and faithful fans recognize in such ringing assertions the Soap Box hype of yore. And most of us, including Dobuzinskis at Reuters, realize that “so far, none of the characters Lee has dreamed up at POW! have come close to achieving the worldwide fame of the heroes he helped create in over five decades at Marvel Comics.” Most of the comic book creations he has launched in the last decade or so have expired after a few issues. No one can doubt that Stan Lee revitalized a moribund comic book industry five decades ago, but, sad to say, the concepts that worked so well for him then are not working these days. But Lee is still riding high on his reputation of yesteryear, a deserved reputation but for accomplishments that have lost their pertinence in today’s popular culture. And despite his recent record, he seems oblivious of any prospect of failure. “I don't feel I'm working,” he enthused to Dobuzinkskis. “I feel as though I'm playing. There are guys 100-years-old who can't wait to get to the golf course. I can't wait to get to the office." More power to him, I say. If you enjoy it, keep right on playing.

A NEIGHBORHOOD STRIP Signe Wilkinson gave up her syndicated comic strip Family Tree just three months ago, but she’s trying again—this time, with a comic strip that will be printed only in her home town, Philadelphia. A once-a-week strip, Penn’s Place started November 20 in the Inquirer (not in Wilkinson’s paper, the Philadelphia Daily News). It’s set in Philadelphia, and Wilkinson intends to keep it local to the extent of sticking to a single fictional city block, to which her protagonist, Hannah Penn, recently moved. Writes the Inquirer’s Ashley Primis: “Readers will meet Hannah's neighbors (the older and younger couples who live next door, the Korean grocer, the bar owner), and see some familiar faces, too,” she continues, quoting Wilkinson: “The mayor will walk down Penn's Place, a homeless person might come into contact with Sister Mary Scullion, and Jose Garces might be looking for a restaurant space. Who knows?" said the cartoonist, whose career we profiled here at Harv’s Hindsight just last month. Penn’s Place may be Wilkinson’s love letter to her home town: she has almost always, through a long career, lived and worked in Philadelphia (except for a three-year stint in California at the San Jose Mercury News). “Her edgy editorial cartoons,” Primis said, “which she continues to draw daily (and which also appear in about 100 other papers and on websites such as Slate.com), have brought her plenty of attention, including being the first female cartoonist to win a Pulitzer, in 1992.” "Philadelphia Magazine once said I was one of the 12 or 13 people who should be run out of town, along with Charles Barkley and Camille Paglia," Wilkinson recalls. "I thought, 'That would be a fun road trip.’” Said Primis: “Wilkinson is well aware that she is one of few women cartoonists whose work is featured in newspapers, and believes it's important that there are women writing female characters. ‘We need to have some balance,’ she says. Wilkinson creates her Inquirer comic strips in her home office, and her editorial ones in her tucked-away nook at the Daily News. "It's such an old-fashioned medium,” she says, “—I feel lucky that someone is willing to pay me to do it."

THE MAUS FOREVER Having won the first-ever Pulitzer bestowed upon a work of comics, Art Spiegelman hasn’t been able to escape his opus. Any time his name is mentioned, the prize-winning Maus is appended to it; or vice versa. To some extent, he is reaping what he sowed: whenever he drew himself in the post-Maus years, he gave his self-caricature a mouse head. And now, with the publication of MetaMaus, he adds fresh altitude to the pedestal he claims to resent having been placed upon. “I’m blessed and cursed by this thing I made that obviously looms large for me and for others,” he told David L. Ulin at the Los Angeles Times. “The result is that I can’t do this thing that seems quite easy, which is: ‘That’s that, and now I’m working on a new thing.’” MetaMaus, which digs deep into Maus’s creation, collecting interviews and sketches that deconstruct his defining work, proves his point with its very existence. And Spiegelman knows it: “If you can’t outrun it,” he said, “just stare the damned beast down.”

MIKE KEEFE RETIRES—ALMOST Last year’s Pulitzer-winning editoonist Mike Keefe has been at his newspaper, the Denver Post, longer than either of his immediate Pulitzer-winning predecessors, Pat Oliphant and Paul Conrad. Conrad left the Post in 1964 after 14 years; his successor was an Australian who revolutionized American political cartooning and then left in 1975 after 10 years. Keefe, who retired, accepting a buy-out, at the end of November, has been at the Post since 1975, 36-plus years. Unlike so many of his political cartooning colleagues, Keefe was not so much forced out as he recognized an opportunity—and seized it. The Post, like most print news media, is hurting financially, and last month, it sought to reduce its payroll burden by offering buyouts, hoping to get 18 volunteers. Keefe looked at the offer. “I had planned to semi-retire in a year,” he told me. “The Post's buyout offer was advertised as a year's salary (in reality it's somewhat less). So, I could work and earn a year's salary or I could not work and earn a year's salary. I did the math. To be clear, the buyout offer went out to a good portion of the staff. They didn't single me out. I felt no pressure to leave. And while layoffs could come if they don't get 18 takers on the buyout, I felt pretty secure. I don't think I was in danger of being laid off. The Post has always treated me well. “It's been an emotional few weeks,” he continued. “Bittersweet. I am sorry to see that they are forced to cut back on staff. The revenue is simply not coming in. Thank you, Craigslist and digital media.” On Sunday, November 27, the Post devoted the front page of its weekly Perspectives section to saying farewell to Keefe. It was a heartfelt send-off, accompanied by a selection of his cartoons. We’re reprinting all of it down the scroll; here are some of the cartoons, plus a few from our own Keefe Kollection.

The article was accompanied by some impressive statistics: an estimated 8,880 cartoons published during his tenure at the paper; 63,096 entries to the weekly cartoon captioning feature. As of November 27, the Post hadn’t decided whether to fill the staff position Keefe leaves vacant. Said Keefe: “Even though there is a long tradition of high quality cartooning at the Post, I'm guessing that it's unlikely that they will seek a replacement. I could be wrong.” About the future of his profession, Keefe added: “There is plenty of incredible talent of all ages in our business. I don't worry about any decline in quality. How they earn a living at is another question. It's a lot tougher now than it was when I started. Clearly cartoonists must create with digital media in mind. Traditional newspapers are going to be a less robust and thinner version of their former selves. Not many will be able to afford to support a full-time cartoonist. That means someone has to crack the code concerning online profits. Till that time, it will be a forum for the dedicated and passionate cartoonist who also works at Starbucks.” About his own future, Keefe was a little more specific. When his wife, who is still employed outside the home, asked him how he was going to spend his time, he answered her in three words: Turner Classic Movies. “She was not amused,” Keefe quickly added. “Actually, I have a number of things in mind: I want to beef up my guitar chops, paint a bit, pick up the slack on Sardonika.com, a satiric blog that Tim Menees and I do. ([Formerly editoonist at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette], he's been doing most of the heavy lifting lately.) And I want to write. I've been researching the armored recon squadron in which my dad served in World War II. I've gotten a lot of riveting material.” And he expects to continue drawing editorial cartoons for Cagle Cartoons, which has been distributing his work for several years. When Keefe joined the Post in 1975, it was the start of his second career. The first, commenced after two years in the Marine Corps, was as a math instructor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, where he completed course work toward a doctorate, but he also cartooned for the school newspaper, the University News. Watergate was headlining the news then, and Keefe became an expert at rendering Prez Nixon’s ski-chute nose. “With material this rich,” Keefe once wrote, “I was fooled into believing that cartooning would always be easy.” He gave up math and went to the Post. At the time, his drawing style, deploying a fragile wandering line, strenuously resembled Gahan Wilson’s. For the last couple decades, though, Keefe has evolved a strong gnarly but simple outline style for delineating his clunky anatomies which he then decorates with restrained flicks of hachuring. When he won the Pulitzer last year, Post publisher William Dean Singleton said Keefe's work underscores the importance of newspapers in generating original content, which, ironically, eventually winds up on the Internet, contributing to the slow extinction of the print medium. Singleton called the Pulitzer recognition “long overdue,” adding: “Mike's been here almost 36 years, and he's put out award-winning work almost since the day he arrived. The two who preceded him were legends. I think Mike is now a legend too." All of our report on Keefe’s winning the Pulitzer can be found at Opus 276. Now here’s the Post’s farewell to its long-time cartoonist, by Curtis Hubbard, editorial page editor.

DRAWING TO A CLOSE Mike Keefe came into my office earlier this month with two pieces of sketch paper and a problem. On one piece of paper, he'd drawn a gut-wrenching image of a naked young boy curled up in a locker room shower with the caption: "Will not be attending any Joe Paterno support rallies." [This cartoon appears in our Editoonery department this time.] It was drawn shortly after thousands of students rallied in part to support the embattled Penn State coach amid reports that he did not do more in response to being told that a young graduate assistant had seen Jerry Sandusky raping a young boy in the locker room showers. The cartoon was picked up and run in papers across the country. After seeing it in the Washington Post, one reader remarked: "My initial reaction was one of amazement that a drawing with so few words could say so much about the misguided priorities of so many. Then, looking again at the drawing, I began crying and had to put the paper down. It brought back to me my experience as a victim of rape and the inaction of bystanders." On the other piece of paper was a cartoon Mike had sketched in honor of Veterans Day, which fell on 11/11/11. [All those 1's cued Keefe.] The picture showed a young boy tapping a decorated veteran on the shoulder, with the child saying, "You're Number One!" For me, it brought back memories of a grandfather who'd served in World War II. In my youth, I never fully comprehended the sacrifice he and other veterans made for this country. The cartoon was a simple yet powerful reminder of the importance of showing our men and women in uniform that we are grateful for their service while we still have a chance. "The Veterans Day cartoon needs to run tomorrow," said Mike, a former Marine. "And I'd like to run the Penn State cartoon soon, while the rally is still fresh in people's minds." In my short time at the helm of the paper's editorial page, I don't know that I'd seen two better pieces. His problem was one that I was happy to solve. We ran both the following day. A few days earlier, Mike was at my desk with a single piece of paper. It was an agreement to accept a buyout that the newspaper is offering longtime employees as we continue to maneuver the industry's choppy financial seas. On that occasion, the problem was mine. Mike was taking the buyout. After 36 years at the Denver Post, he is leaving us at the end of this month. Today we celebrate Mike's career with a selection of some of his more memorable cartoons. Given the thousands he has drawn in his time here, the available space does his body of work little justice. But we could not let him go without thanking him for all he has done for this enterprise. A mathematician by training, Mike was teaching at a college in Kansas City in 1975 when a side job drawing cartoons became an invitation to be a full-time cartoonist at the Denver Post. Earlier this year, he was awarded our profession's highest honor: the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. Like John Elway [formerly, long-time Broncos winningest quarterback, still a local hero], Mike is going out on top. I have had the pleasure of working with him for only a few months. Former editorial page editor Dan Haley, who worked with Mike for years, summed up his impact well in a column earlier this year. "In the years I've worked with Mike, I've never stopped marveling at how he can distill a complex issue, or a prickly political fight, into a concise, compelling opinion with just one image," Haley wrote. "In one frame, he tells the stories of our times better than most keyboard-punching reporters or editorialists. Journalists are always jockeying for more space — just a few more words, a few more inches — but Keefe needs just a handful of words to deliver a powerful punch." It's too soon to know exactly what we will do in his absence, but I take some comfort in knowing that we are not losing him entirely. Mike will continue to syndicate cartoons on a weekly basis, and we will have access to a smaller sampling of his work that way. Selfishly, I wish that he was not leaving, as I know that his work makes this a better newspaper. But Mike lives a rich life outside these pages, and it comes as little surprise that he is ready to move on to his next remarkable phase. We wish him well. IRONICALLY,

after all the fine sentiment, the Post editors rejected Keefe’s last

ANOTHER EDITOONIST QUITS At the DailyCartoonist.com, Alan Gardner alerted us on November 1 to the retirement of John Sherffius, the editorial cartoonist for the Boulder Daily Camera. Sherffius, whose symbol-ridden cartoons are among the profession’s most powerful and imaginative, is not simply retiring from the newspaper: he’s leaving the profession. Gardner quotes the e-mail Sherffius sent to the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists email list group: “I wanted to let you, and the AAEC, know that this will be my last week at the Daily Camera, as I am retiring from editorial cartooning. I informed my editors and Creators News Service at the beginning of October, but I wanted to wait before letting the AAEC know until the Camera readers were informed today. I’ve had a great career in editorial cartooning and I’m very thankful. However, I’ve been in this field since college and I think a change will do me good. I’m looking forward to pursuing other artistic endeavors.” To the readers of the Daily Camera, Sherffius wrote: "It's been a tremendous privilege to comment on the news and express my opinion on local, national and global affairs. I have enjoyed every minute of it. However, after so many years in this business I'd like to pursue other creative endeavors and, not incidentally, begin to prepare the bank account for the kids' college tuition! And thank you, readers, for the opportunity to be a part of your morning routine." Editor Erika Stutzman added: “Working with Sherffius was a real pleasure, not only because of his talent and professionalism, but because he is a genuinely pleasant and thoughtful colleague, and someone who cares deeply about the world around him. We'll miss seeing his name and his thought-provoking work on our pages.” Sherffius started editorial cartooning for the campus newspaper, the Daily Bruin, while a student at the University of California at Los Angeles. He graduated with a BA in psychology in 1984 but found no openings for editorial cartooning; he went back to school, graduating in 1986 with a second BA, this one in graphic arts, from California State University. After several positions as staff artist, he found in 1992 a similar position at the Ventura County Star that offered him the chance to do editorial cartoons in addition to graphs, maps and the like. Before long, he was doing six editoons a week. With that experience under his belt, he left in 1998 for a full-time staff editooning job with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, but he resigned in December 2003 because a new editor’s ideas and his didn’t coincide much. After freelancing and syndicating, still, Sherffius moved to Denver in 2005 and found a situation at the Daily Camera. He won the Herblock Award in 2008, a signal distinction, perhaps the highest prize the profession offers. And now—who knows? But with his talent, he won’t be wandering long, I wager.

Footnit: With the departures of Sherffius and Keefe, the number of editorial cartoonists has reached an all-time low. Counting David Horsey, erstwhile staff editoonist on the now defunct Seattle Post-Intelligencer but still full-time with the Hearst organization, the number of full-time staff political cartoonists in the country is 66, down from 101 in May 2008—a loss of 35% of the staff positions in three-and-a-half years.

READ AND RELISH Let’s take a break with a few bon mots: “Never hit a man with glasses. Use something much heavier.”—Anonymous “A good listener is not only popular everywhere, but after a while, he knows something.”—Wilson Mizner, playwright “Humor can get in under the door while seiousness is still fumbling at the handle.”—G.K. Chesterton “The best thing about the future is that it comes only one day at a time.”—Abraham Lincoln

UNCHARGING A SUPERHERO Ben Fodor, the Seattle resident who wears a black mask with yellow stripes and a bulging muscle body suit and calls himself Phoenix Jones, a superhero whose self-imposed duties included patrolling the streets and battling miscreants, won’t be facing charges for pepper-spraying a group of people brawling outside a downtown nightclub. Officials decided not to press charges; they’d initially thought the bulgy Fodor started the brawl by spraying the unruly bunch, but they couldn’t find two of the people pepper-sprayed to testify and without such testimony, they figured no jury would be persuaded of Fodor’s guilt. Fodor wore his uniform to court last month, removing his mask when asked by a court factotum. And he dramatically removed it again outside the courthouse when speaking to the assembled multitudes: “I will continue to patrol with my team,” he said, “—probably tonight. In addition to being Phoenix Jones, I am also Ben Fodor, father and brother. I am just like everybody else. The only difference is that I try to stop crime in my neighborhood and everywhere else.”

Vocabulary Enrichment AT THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA, as at many other Institutions of Higher Learning, they’ve started teaching a comics course—not how to draw but how to read and appreciate. “Comics scholars feel they’re exploring the last pop-culture medium to earn critical and aesthetic examination,” reports Lin Larson in the alum newsletter, Spectator. But the comics course instructors have discovered that while primary material abounds (reprints of classic newspaper strips, graphic novels, etc.), not much theoretical literature exists. Says Corey Creekmur, who holds a joint appointment in cinema and comparative literature: “We don’t have an established formal vocabulary like we have for film. What do you call sweat beads that indicate a character is worrying, or the little lines that show surprise?” Those’re called plewds and enamata, as any reader of Mort Walker’s Comicana knows. And the aesthetic and critical vocabulary Creekmur is looking for can be found in my two foundational works: The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History of the Newspaper Comic Strip and The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History. You can buy them both here, Corey. They’d make excellent Yuletide offerings to your friends and cohorts.

A LITERARY GIANT STEPS DOWN The surviving co-creator of the French comic strip Asterix has announced he will retire and hand the series over to a younger artist after 52 years of drawing the characters, reports James C. McKinley Jr. at the New York Times artsbeat.blogs. At 84, Albert Uderzo, who created the diminutive Gaul with writer Rene Goscinny in 1959, said that he would let his successor pen the 35th volume, due out next year, according to theaustralian.com.au. "I'm tired,” Uderzo said. “The years have gone by and these years weigh heavily. I have decided to leave this to young authors who certainly have enough talent to do it." But with a flourish worthy of Asterix, Uderzo has so far (as of September 27) declined to name his successor, setting the Parisian rumor-mill into overdrive. "It's an artist who has followed us for a long time in the bosom of the studio," he said, smiling coquettishly no doubt. The position is one of the most coveted in comics, given that 350 million books compiling the strips have been sold since the first in 1959. Uderzo dismissed speculation that the indomitable Gaul would end his career of resistance to the Romans. "Asterix will live. And me, I'm not yet retired," he said. "I am going to help my successor to create the next book. It is excessively dangerous to take over a series which is 52 years old, with 34 volumes and such success. But we've got to try because that is what readers want." However, many Asterix fans may also be hoping Uderzo takes a back seat in the next production, since purists say the series lost its magic when Goscinny died in 1977 and Uderzo took over the scripts as well as the drawings. Still, “it's rather more remarkable that Uderzo kept Asterix going so long on his own [34 of the feature’s 52 years],” said Samira Ahmed at guardian.co.uk. “Part historical fantasy, part a kind of Private Eye, packed with the harmless violence of ‘pafs’ and ‘tchocs,’ the world of Asterix was a unique dual creation. Multilingual Goscinny brought the literary allusions—there's an entire page of Caesar's Gift where Asterix duels a Roman soldier in the style of Cyrano de Bergerac. Uderzo matched him with meticulously researched and drawn landscapes, architecture and visual puns, such as the reference to Géricault's painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ in Asterix the Legionary. “Because it looked as good [as the collaborative effort],” Ahmed continued, “we ignored the fact that most of the stories, apart from a couple of notable exceptions (Asterix and the Black Gold, Asterix and the Great Divide) were much poorer after Goscinny died.” But, he goes on, “Uderzo deserves recognition for the scale of his achievement; much of it in the long-running Pilote comic, where Asterix first appeared. A master draftsman and a cinematic storyteller, in his use of epic set pieces, cutaways and closeups, he's drawn 400 unique characters to date in Asterix alone. “He revels in all the variants of Gallic physiognomy (bullying Crismus Bonus in Asterix the Gaul looks unnervingly like Dominique Strauss-Kahn) but Uderzo, born of Italian immigrant parents, also delighted in national types—the separate tribes who join together to fight the global corporatization and arrogance of the Roman empire. From the moustachioed, hot water-drinking Britons to the proud Corsicans with their dangerous cheeses, Uderzo has gently mocked, but also shown affection for, individuals who stay true to themselves. So after so many years, would it have been better to have said it just ends with me, as Charles M. Schulz did with Peanuts?” Probably not. Besides, Peanuts hasn’t ended with Schulz’s death.

NEW PEANUTS The Peanuts franchise is simply too big a cash cow. No one—the Schulz family, the syndicate, Creative Associates (the staff assembled by creator Charles Schulz), and legions of fans—could realistically be expected to abide forever by Schulz’s parting behest that his work not be carried on by a successor. It has always been happily endorsed by many of us that Schulz’s wishes honored, that the work of his genius be allowed to rest undisturbed—to continue in reprints, of course, as a kind of monument to his achievement, but not to be added to by anyone. Alas, that was too much to expect. The franchise, as I said, is simply too potent with revenue-generating possibilities. Since Schulz’s death, the franchise continued for some time without adding anything new to the canon—i.e., the comic strips that comprise Schulz’s life work (and, according to him, his life itself). And the restraint, admirable though it is, is now giving way to temptation. A new tv special came out a year or so ago, if I remember. In homage to Schulz’s wishes, it was said that he had worked up the script before he died, so this latest production was actually the realization of his intention. Okay, we accept that. And then came last spring’s graphic novel, Happiness Is a Warm Blanket, Charlie Brown. That, we gathered, employed tropes Schulz had long established in the strip. Okay, we accept that—just as we would accept any other graphic novels cobbled up from the tv animations. But now comes the comic book. Here we slide further down that slippery slope. Schulz’s wishes, we may presume—branching out into a fresh new interpretation of them—apply only to the syndicated newspaper comic strip. I don’t know, for any sort of fact, whether this is the kind of rationale that permits new Peanuts material to surface; but I can easily imagine that it worked somewhat in this fashion. And so the Peanuts comic book is permissible: it does no violence to Schulz’s wishes. New Peanuts comics can be concocted; other cartoonists engaged to draw them. Besides, an awful lot of people—family and staff—depend upon the revenues that Peanuts generates. I don’t mean that in any snide way. It’s simply a fact. And as their expenses heap up, more revenue is needed. They can’t go on forever just selling ceramic Charlie Browns and Snoopys. Other ways of exploiting the franchise must be explored. The Peanuts comic book is one such foray. The “Special Preview Issue,” No. 0, is now out. It reprints several Sunday Peanuts strips (“Classic Peanuts Strips”) by Schulz, thereby justifying (probably) the use of his name on the cover. The rest of the interior consists of short stories by Ron Zorman, Paige Braddock (creative director of Creative Associates), and Vicki Scott. In future issues, they will be joined by others—Shane Houghton and Matt Whitlock, according to a notice from the publisher at its website, BoomStudios. The chief challenge the artists face is presented by the comic book format itself. Schulz produced page-size strips on Sundays, but he never varied the grid-format of the newspaper comic strip even on Sundays. The comic book form offers opportunities in layout and page design. Said Braddock: “We’ll fully exploit the sequential art storytelling of traditional comic books. However, the full-page format will give us more room to expand backgrounds and story context. Breaking out of the horizontal comic strip format will allow for more visual storytelling. I think this will be more of a style that younger readers are used to, and our goal is to stay true to the editorial guidelines that Schulz set forth—so, hopefully, more seasoned fans will be pleased as well.” An

example of the way page layout is being exploited is posted nearby. The Happiness graphic novel was even more flamboyant in some of its page designs. “Rather than trying to do one longer 24-page story,” Braddock continued in her interview with Cliff Biggers at Comic Shop News, “the monthly issues will contain a couple of 8-page short stories. The stories are fun and quick for those of us with shorter attention spans.” The themes and characterizations of the new material will be based upon Peanuts in the 1960s, she said. “This seems to be the period where Schulz really hit his stride and had established the major characters and themes. Also, as far as the art goes from this period, there’s a lot of really funny source material to pull from for inspiration.” Braddock hopes to attract young readers; at least a generation of readers has grown up without seeing new Peanuts material. “When I was a kid,” she said, “Snoopy was the character that inspired me to be a cartoonist. I want kids today to have the same inspiration. ... The problem is that kids don’t read newspaper comics, so for them to meet the Peanuts characters, we have to be where kids are. Hopefully, creating these comic books will help us do that.” I applaud the impulse, but I’m not sure that today’s kids are the kind of comic book readers Braddock envisions. One of the problems plaguing the industry is that the reading audience is growing older—and comic book publishers increasingly appeal deliberately to that older reader. Are there any substantial sales of comic books to young readers? Pre-teen readers? Maybe. But I’m not confident about it. Because Schulz permitted Peanuts comic books to be produced with new material during his lifetime, it may safely be assumed that he would not mind a prolongation of that scheme now. Still, among Peanuts fans are many whose knickers are in a knot about it. I have mixed feelings myself. Clearly, the rationales I’ve suggested here for the continuation of Peanuts in every venue except the newspaper comic strip section are acceptable. Nothing particularly underhanded about them. But it’s clear after reading the new stories in Peanuts No. 0 that, however humorous and even delightful they are, they’re not Schulz’s Peanuts. The drawings are very good, as perfect an imitation of the Master as anyone could want. But the spirit of the stories is not Schulz’s. They’re more exuberant than he usually was. They have more action and less heart. More akin to the animated Peanuts than to the syndicated, static Peanuts. And so the new Peanuts is a mild dose of disappointment. But what do we expect? Schulz? Not likely. There was only one of him, just once. And that is the reason that he wisely desired that no one try to continue Peanuts after he was gone. That was Schulz the artist talking. But Schulz was also an entrepreneur, manager of a monumentally successful commercial enterprise. In the various Peanuts projects that have surfaced since his death, his successors do their best to honor the wishes of the artist—to preserve that part of Peanuts that was closest to his heart, the strips—but they have also paid heed to the entrepreneur. And we’re likely to see in future issues of the new comic book the stories that Schulz himself produced—all of the first comic book incarnation in 1954—before turning that endeavor over to Jim Sasseville and then Dale Hale, who, it is reputed, did all the rest. So for a short time sometime soon, we’ll have both the artist and the entrepreneur in the new comic book series.

WILL THE INTERNET SAVE US ALL? The comic book industry, which has been experiencing a slow downward spiral in sales for years, is now grasping at a way to stop the tail spin—the Internet. Most comic book publishers have been approaching the digital ether cautiously: if an electronic edition of a book is issued, it doesn’t hit the Web until weeks—often months—after the print version appears. DC Comics lately took a huge step into the unknown: all of its New 52 titles were digitized and posted on the Internet the same day the print versions hit the racks in comics shops this fall. "I love digital comics. I will always have a heart for paper and a book I can hold, but I have an iPad that is stocked with comics," Kelly Sue Deconnick, a new writer for Marvel Comics, told Arman Aghbali at Commerce Times. Deconnick carries at least fifty comics with her at any given time, since those issues weigh no more than her tablet does. "I have a favorite reader,” she said, “and I love the ease of downloading. I read most of my comics this way.” Some complain that the price of digital comics is too high and that the way comics are edited to fit on a phone or tablet fundamentally changes the way comics are read. "If [comics publishers] want to reach a wide audience, their price has to be two digits, 99 cents. That's the magic number where it doesn't feel you're spending money," says Cameron Stewart. Stewart is an artist whose work includes a run on Batman and Robin, and his own award-winning webcomic, Sin Titulo. Print comic books are currently priced at $2.99 and $3.99, depending on size. Stewart believes that the closer you get to five dollars, the more the consumer has to think about what they're purchasing. Ty Templeton, a comic book creator who's worked for Marvel and DC Comics for popular series like Justice League International and Batman Adventures, doesn't mind either format. He likes web comics and has all of his comics for sale online. But he sees a bigger issue with the digital format than the price. He believes that it fundamentally changes the way comics are read. "A lot of apps show the comic panel by panel, and for a comic, that's like watching a movie in the 80s,” Templeton said. “You would lose a bit of the left and the right, and soon, the movie ‘Seven Brides for Seven Brothers’ becomes five brides for four brothers. It doesn't work." Apps like ComiXology tend to show comics through individual panels, due to smartphones' smaller screens. Without this feature, the dialogue and narration become difficult to read. Said Templeton: "I object to the idea that you have to change the shape of the screen to enjoy the content." Deconnick, though more positive, admits that "digital doesn't work with the double-page spread." A picture spread over two facing pages is a maneuver often used for dramatic impact and surprise. Not in digital comics. Not yet. Said Deconnick: "Because you have to pull out and shrink down to see the full image on a double-page spread, and then zoom in to see the detail, it doesn't have the same power as it does [in print]." “While discussion behind digital comics isn't exactly unanimous,” reported Aghbali, “almost everyone agrees that it's the way of the future, whether the publishers take initiative or not. Ask any creator if their work is available online and the answer is a resounding yes; though they'll add that they didn't have choice in the matter. ... Despite many of the challenges ahead for comics distribution and sales, there is an overwhelming belief that digital comics and web comics are expanding the medium and the readership.” He continued: “Stewart is confident that web comics are the next stage in comic production. He's willing to bet that Marvel and DC would generate a lot more interest if they had exclusively online series. Not to mention that he thinks focusing on the Web will fix many of the glitches found in digital comics.” Aghbali goes on to quote Stewart: "Print comics are limited by the amount of ink you can fit on paper, but online you can do whatever you want. If you think about the aesthetic of digital, one panel at a time, you'll be able to take advantage of it. There's a concept in comic design called the ‘infinite canvas’ which implies that on the web, you have literally infinite space to make a story. No need for turning a page at all. No matter where this industry goes, I'm sticking with the web. I'm at a stage in my life where I don't like accumulating stuff.” “Many love saying good bye to dusty basements and garages filled with thirty-year-old periodicals,” Aghbali said. “The iPad can store just as many issues of X-Men and Wonder Woman without all the clutter. Yet, Templeton is quick to remind people that there will always be a place for print comics.” And he finishes by quoting Templeton: "If you want a first edition copy of the Old Man in the Sea by Ernest Hemingway, you're going to pay a thousand dollars for it while the paperback is out this week for eight-ninety-five. And there's a reason for that," he concluded: "Print is a moment in history that you can hold in your hand."

NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIPS are another species that’s become endangered because their platform is collapsing: newspapers are in financial peril because they’re losing readers and advertisers to the Internet. But some comic strip cartooners see salvation in the Web. Dave Kellet, for instance, has appeared twice at recent cartoonist gatherings (Festival of Cartoon Art at Ohio State University a year ago and National Cartoonists Society in June in Boston), both times as a drum-banging advocate of the money-making potential of comics on the Web. A few years ago, he moved his comic strip Sheldon out of print syndication and onto the Web, saying it generated more income for him in the electronic ether than on newsprint. (Kellet, incidentally, is one of those behind “Stripped: The Comics Documentary,” a video being funded through Kickstart and produced by Kellet’s Small Fish Studios.) And Kellet is not alone in singing the praises (and the money-making cache) of the Web for cartoonists. Last July, after a five-year run, Aaron Johnson ended print syndication of his strip WT D (or What The Duck as fans knew it before the title was changed for syndication, adds Alan Gardner, who interviewed Johnson at DailyCartoonist.com). He wanted more time to devote to other projects he told Gardner. But many of the projects seem rooted in the webcomic, so Johnson continues the feature on the Web but not as a daily cartoon: instead, it shows up once a week, on a Monday, which Johnson says is the high traffic day. Said he: “I still continue to self-syndicate the comic to print publications domestically and internationally. I miss writing the strip every day, but not as much as I'm enjoying this—how do you say it?—free-time.” He fully intends to continue the strip as a webcomic: “These last couple of months have confirmed that dialing back the production hasn't changed things much. The fan-base continues to grow, licensing offers, speaking engagements, publication requests, sales—keep coming in. The difference is now I can devote the proper amount of time and energy to those things. ... My laundry list of things I want to do (both WTD related and not) has gotten too large and too long ignored. I've had to turn down too many opportunities over the years simply because there weren't enough hours in the day.” Asked to compare his print syndication experience to his Web experience, Johnson said: “Here's the thing – I never set out to be a comic strip cartoonist, period. So everything has been icing on the cake. Syndication was great. John Glynn [his editor at Universal Press syndicate] is an awesome guy. To Universal's credit, they were completely supportive and never got in the way of what I was already doing. In the big picture, newspaper syndication was just another revenue stream and audience for What the Duck (as is self-syndication, licensing, merchandise, advertising, etc.). If you have something that people are interested in reading, you'd be foolish not to explore any and all forms of media and methods of distribution out there. “As far as some tangible experiences between newspapers and web,” he continued, “—it’s easier to have relationships with your fans online. There's a little bit of a disconnect with readers who are only following you via the newspaper. I guess you could compare it to a two-way and one-way street. Online, you instantly know what works, who's reading it, immediate feedback from your audience, etc. With the newspaper audience, it's a little like throwing a message in a bottle out into the ocean everyday. You know it has the potential of reaching millions of people, but you don't really have a good idea who and how many people are reading your work everyday. Again, I had a wonderful time with newspaper syndication (and the Andrews McMeel book) and if there is a newspaper market for a ‘Monday Comic,’ I'm game.”

TINTINABULATIONS ABROAD AND HERE From ContactMusic.com: It didn’t open in Europe until October 26, and it won't be seen in the U.S. until December, but Steven Spielberg's motion-capture “The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn” is already drawing much criticism from fans of the original Hergé comic strip and those who have accused the Belgian writer/artist of racism, anti-Semitism, and sexism. Typical of the fury ignited by the movie, Nicholas Lezard, the literary critic for Britain's Guardian newspaper, said that when he left the theater showing the Tintin film, he found himself "too stunned and sickened to speak; for I had been obliged to watch two hours of literally senseless violence being perpetrated on something I loved dearly. In fact, the sense of violation was so strong that it felt as though I had witnessed a rape." If other fans of Hergé react the same way, it could diminish the value of Tintin books and merchandise, which have remained top retail sellers overseas, other critics of the movie suggest. "There's a risk that Spielberg's vision will undermine Hergé's," Jean-Claude Jouret, a former manager of Hergé's estate, told Agence France-Presse, the French news agency. Making the movie, he said, was "undoubtedly good business but perhaps it won't help the longterm preservation of Herge’s work." Meanwhile, critics of Hergé are wondering why Spielberg would ever have wanted to associate himself with the man. They note that a court case is currently festering in Brussels in which a Congolese citizen is demanding that Tintin in Congo be banned because it amounts to "a justification of colonialization and white supremacy." They note further that Hergé was arrested after World War II for collaborating with the Nazis and inserting anti-Semitic subplots in Tintin stories. And Matthew Parris, a columnist for the London Times, noted that there is virtually a complete absence of women from Hergé's stories, a condition also apparent in Spielberg's movie.