|

|||||||

OPUS 226 (July 13, 2008). We report this time, at great length, on the recently concluded annual convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, which brought its struggle against overwhelming odds to the Alamo, whereupon we unearth a rare artifact, Texas History Movies, and explain its name. We also review Betsy and Me, a book reprinting Jack Cole’s last work of genius, and we ponder the inexplicable Nancy on a billboard and Samuel Beckett’s fascination with the Bushmiller strip. All that and the usual round-up of some news and minor reviews. And now, here’s what’s here this time, in order, by department:

NOUS R US Manga

in France, Rotten in Denmark, Mile High Flood, Sadie at Death’s

Door, McKinnon’s Editoon Turns on Him, Erik Larsen Steps Down

at Image, Time Finds Comics in Movies, How

Nancy Inspired a Road Sign and Samuel Beckett ASSOCIATION

OF AMERICAN EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS LBJ AND ART WOOD, LOVERS OF CARTOONS Remembering

the Alamo: Texas History Movies Comic Strip Batman

and Robin the Boy Wonder Reviewed, Sort Of ONLY

PASSIN’ THROUGH ANOTHER

OF THE WATERSHED WORKS OF JACK COLE FUNNYBOOK

FAN FARE BOOK

MARQUEE COMIC

STRIP WATCH And

our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom

Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version”

so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment for

reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further

adieu—

NOUS

R US The ninth outing in France of Japan Expo, a July 3-5 celebration of Japanese pop culture, expected over 100,000 fans of all things manga-nese, comics, anime, video gaming, fashion. Last year's expo drew 80,000 people over three days according to AFP, which explains that “one in two French children are thought to have read at least one manga comic, and an entire French generation was reared on a diet of Japanese animated television cartoons. With France now the second biggest market for manga outside Japan, there is also a growing interest in other sides of Japanese culture.” ... From John McCarthy, one of our incurable spies, this alert: On Wednesday, July 16, the History Channel will present “Batman Unmasked: The Psychology of the Dark Knight,” a program that promises to “delve into the world of Batman and the vigilante justice that he brought to the city of Gotham. Batman is a man who, after experiencing great tragedy, devotes his life to an ideal—but what happens when one man takes on the evil underworld alone? Examine why Batman is who he is—and explore how a boy scarred by tragedy becomes a symbol of hope to everyone else.” ... The Danish Supreme Court on July 2 ordered a new detention hearing for two the Tunisian men held on suspicion of plotting to kill Kurt Westergaard, one of the twelve cartoonists who drew the Muhammad cartoons that provoked a deadly uproar in the Muslim world in 2006. The two men have been held since their February 12 arrest, pending possible deportation without trial. Denmark's intelligence agency, reported the Associated Press, has said it considers the men threats to national security. ... Also in Denmark, an appeals court recently denied the appeal of seven Muslim groups that sued Jyllands-Posten newspaper and two of its editors for defamation by means of those cartoons caricaturing the Prophet two years ago. According to jurist.law.pitt.edu, the court agreed that while some Muslims might be offended by the cartoons, the pictures and the paper were exercising their right of free speech. In contrast, in Jordan in 2006, the editors of two national newspapers were convicted and sentenced to two months in prison for reprinting the cartoons. In January this year, a former newspaper editor in Belarus was sentenced three years in prison for the same crime. One

of the three Mile High Comics shops

in Denver was flooded on June 13 when a water main broke in the rear

of the building. The flooded store was the largest of Chuck

Rozanski’s stores, but damage was

limited. As it happened, about three dozen people were in the store

for the weekly magic card tournament, and when the “geyser-like

flood of water” came into the store, they positioned a table to

deflect the spewing water back out the rear door of the building.

They also immediately moved boxes of comic books, posters and games

off the floor to elevated locations. “If they hadn’t been

there willing to get themselves all wet, the damage could have been

much worse,” said Rozanski, who, according to Kathryn Richert’s

story in YourHub.com, was in New York at a comic show at the time.

“Water wasn’t turned off for four hours,” she

wrote, “and damage added up to about $20,000,” a pittance

for an operation that is one of the country’s largest. But most

of Mile High’s inventory is held in a warehouses away from the

stores. ***** DEATH IN THE FUNNIES Another character in Rudy Park verges on death. “In January 2007, Mort Park passed away in the United Media comic,” Dave Astor remembered at Editor & Publisher. “Now another octogenarian, Sadie Cohen, has a tumor in her throat that may or may not be malignant. Soon after Sadie was diagnosed last month, reader Heidi Pottinger of Denver ‘hijacked’ the strip to demand that the character not die. But the Heidi Pottinger who readers saw in Rudy Park is a fictional character herself, according to Matt Richtel,” who writes the strip (assuming, for the purpose, the name “Theron Heir”; Darrin Bell of Candorville draws it). Pottinger urged readers to write in to save Sadie, and Astor reported that 100 responded during the first two days. "The

lion's share want to see Sadie saved,” Richtel said, “but

there are some brutes out there who says things like ‘kill off

the old bat.’ Others don't find anything funny about death, or

its prospect, in the funny pages." Richtel, author of a novel

called Hooked, who

keeps secret his identity as a reporter for the ever-dignified New

York Times, explained the macabre plot

development by blaming the Internet: "We've been trying to make

the strip more interactive, in the spirit of the Internet age,”

he said. He and Bell will listen to what readers have to say, but in

the last analysis, Sadie’s fate will be decided by Rudy

Park’s creative duo. The strip’s

current sequence has John McCain at a "charisma boot camp,"

but the strip will soon return to the Sadie storyline, if, as you

read this, it hasn’t already. ***** WHEN EDITOONING TURNS UGLY If the Danish Dozen didn’t convince newspaper editors of the power of editorial cartooning, then Bruce MacKinnon’s recent adventures should. About six months ago, MacKinnon, who cartoons north of the border for the Halifax Chronicle Herald, drew a cartoon of Barack Obama on the front lawn of the White House next to a sign reading “White House” and thinking, "Well first off, that sign's gonna have to go." MacKinnon told Chris Lambie at the Chronicle Herald that most people he heard from at first saw the humor in the line. "The name White House, as the home of the president, seemed like a huge metaphor for white male domination of that office," MacKinnon said. “So the whole idea just seemed like an obvious cartoon concept to me. I almost didn't do the cartoon because I thought it was too obvious." Soon, however, his cartoon started showing up on websites based in the U.S. And that’s when the trouble started. "The first wave of letters was from Republicans and right wingers who admitted that they'd never vote for Obama themselves, but they were offended on his behalf," MacKinnon said. Then a few weeks later, altered versions of the cartoon started appearing. Sent via chain e-mails, one version of the bastardized cartoon includes the star and crescent symbol of Islam and a logo of the fictitious Anti-Christian Lawyers Union, with the slogan "Jihad with a law degree." It also makes several false claims, Lambie notes, “including that Obama used a Qur'an when he was sworn in as a senator.” "I love that my cartoons are getting out there,” MacKinnon said. “But, obviously, that's twisted and isn't my cartoon anymore. It's been hijacked and that's not a good feeling.” He’s been receiving e-mails for months from people incensed over what they believe to be his cartoon. "This is the really disturbing thing about the Internet," the cartoonist said. "It's one thing if someone steals your car and you never see it again. It's stolen. It's gone. But if they steal your car and paint profanities on it and they're driving up and down your street with it every day—. I have to look at my stolen cartoon coming back to me in e-mail almost every day distorted in such a way that I can't even recognize it and knowing that it's out there with my name still on it." MacKinnon is also being blamed for racist buttons sold last month at the state Republican convention in Texas that read: “If Obama is President . . . will we still call it the White House?” The pin's creator, Jonathan Alcox, confirmed that MacKinnon's cartoon inspired the bad taste buttons. Alcox’s presence at the convention was paid for by some Texas Republicans, but Alcox has been told by the state’s Republican chairman that “he need not apply to another Republican state convention,” adding: “We wanted to send a clear message that we were neither going to tolerate nor profit from any form of bigotry." Alcox declined further comment when contacted by Lambie, explaining that his button had inspired death threats and he had to disconnect his phone. “I had ten days of hell,” he said, “and it’s finally dying down.” MacKinnon

has received some “scary” phone calls, he said, but no

death threats. "I'm up here in Canada, and they're writing from

the U.S., so I think they'd have to want to travel," he said.

"And you know, gas is just too expensive now. I think I'm safe

for a while." ***** The Fourth of July was celebrated in many of the news media by recording the death of South Carolina’s Jesse Helms, a show-boating bigot in the U.S. Senate for thirty years until he relinquished his seat in 2002 to Elizabeth Dole. Almost without fail, obits, if they went on long enough, mentioned that Helms, dying on Independence Day, duplicated the dubious achievement of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who also expired on a July 4, thereby insulting two of the nation’s most distinguished founders by linking them with a racist conservative. Adams and Jefferson were probably conservative, too, for their day, and probably racist as well, for ours. But they accomplished more for the nation than Helms ever dreamed of. Too bad Larry Harmon, who died the day before, July 3, couldn’t have waited a day, then we could have had headlines about two “Bozos” disappearing at once. But that would have been unkind and unfair to Harmon, who bought the “rights” to the tv clown persona and turned the character into a franchise, embellishing Bozo's distinctive look with the orange-tufted hair, the bulbous nose, the outlandish red, white and blue costume. ***** According to CBGXtra, the online breaking news arm of the Comics Buyer’s Guide, Image’s publisher Erik Larsen has stepped down from his position and has been replaced by another Eric, Executive Director Stephenson, “effective immediately.” The company’s official release reports Larsen as saying: "Being the publisher has been a blast, but it's long past time I put my focus on what matters most to me—creating new comics [namely, the Savage Dragon, I hope—RCH]. We accomplished the goals I set out for the company, and it's long past time for me to go back to doing what I do best. Even more so, I feel Eric deserves the position as he's completely instrumental in our company's recent success. It's an honor to hand him the reins." Stephenson

was with Image at the beginning in 1992, when he was Jim

Valentino's assistant. He later went on to

work as the managing editor of Rob Liefeld's Extreme Studios before returning to Image as Director of Marketing in

2001. Stephenson became Executive Director in 2004. On his promotion,

Stephenson said, "Even after over sixteen years of working with

Image off and on, I'm more excited about the company now than I've

ever been. The unprecedented variety of creators, genres and formats

we've been publishing really reflects what I love so much about this

medium, and I'm looking forward to carrying on and growing upon this

tradition." ***** THE COMICS IN MOTION Time magazine for June 30 carries a 3-page article declaring that “graphic novels are Hollywood’s newest gold mine.” Well, yes: but we saw that happening months—even years—ago. Time, however, has apparently just discovered that graphic novels are popular with movie-makers because “in a risk averse era, comic book adaptations have a distinct advantage: the drawings mean studio execs can see beforehand what the movie will look like.” Well, yes again; but I think it’s more than that. Superheroic deeds of derring-do are inherently exciting. Superheroes flourished in comic books—and comic books flourished because of the superheroics—because the four-color print medium could convincingly portray the longjohn legions flying around, something no other medium, certainly not the movies of the time, could do. But as motion picture technology advanced, it became possible, more and more, to portray on the screen the antics heretofore confined to pulp paper. Remember the sales pitch for the first Superman movie? Something like—“You’ll believe he can fly.” And we did. As the movie industry became more and more sophisticated in its special effects endeavors, so were movies more and more able to duplicate the excitement of comic books. And the more Hollywood became wedded to special effects violence, the more comic book action was suited to motion pictures. Picking comic book heroes to make movies about was, perforce, a no-brainer. Incidentally, I suspect the reason that the first “Captain America” movie flopped in 1990 was that its makers didn’t want to spend the money for special effects; at the time, the lone successes of the Christopher Reeve’s four Superman movies hadn’t, apparently, been persuasive about the essential need for investing in special effects. It took the first Spider-Man movie, then the X-Men venture—not, I beg to differ, “300"—to convince the movie moguls. Time says Frank Miller’s “300" was the turning point. I suspect we’d passed that point much earlier, as I’ve intimated. But the fascinating thing about Miller’s role, when you think about it, is how large he now looms in the history of four-color fantasies, from pulp paper to motion pictures. He showed how to manipulate space and how to use pictures for narrative impact with his first mainstream assignment at Marvel, Daredevil. Then he created the grim and gritty superhero with Batman: The Dark Knight in 1986, a tale told in the wholly unconventional graphic style he adopted with Ronin in 1983-84. Then came more stylistic innovation with his Sin City titles. Not content with revolutionizing the funnybook medium, he took up movies, co-directing the first “Sin City” flick, adapting it from his static imagery in the comic books. “300" was the next step in making movies directly from comic books. And then, next winter, we’ll get Miller’s Spirit movie, yet another venture in the same direction. As much as Miller professes admiration for one of comics pioneers, Will Eisner, Miller himself has become almost as legendary a pioneer as Eisner. DreamWorks Animation’s “Kung Fu Panda” is already the most successful foreign film in China, writes Maria Trombly online, taking in $14 million during its first 10 days in the country. ... Turner Broadcasting will start airing the new “Garfield” series, 52 ll-minute installments, from France’s Dargaud Media next year on the Cartoon Network, according to Editor & Publisher. Box

Scores. As of July 7, Will Smith’s

“Hancock” had won its opening weekend revenue race with

an estimated total of $66 million. It was Smith’s eighth number

one opening in a row, and “Hancock” now seems poised to

contend with “Iron Man” and “Indiana Jones and the

Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” for the summer box office

championship if it can reap $300 million or better over the next

weeks. “Iron Man” is the current leader with $311.7

million; “Indy,” second with $306.6 million. “The

Incredible Hulk,” meanwhile, has accumulated just $125 million

in ticket sales so far, piling up an unexpected $54.5 million its

opening weekend. Pixar’s happily received “Wall-E”

has already passed the Green Giant with $128.1 million in revenues.

Who can keep track of all this fiscal matter? Not me, not ever again. ***** ARCHETYPAL NANCY Artist Joe Brainard became infected with Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, and in 1963, he began “reimagining” the character, producing, over the next fifteen years, more than 100 Nancy-based works (“If Nancy Had An Afro,” “If Nancy Was An Ashtray,” “If Nancy Was a Da Vinci Sketch,” etc.), many of which are now reproduced in a new book, The Nancy Book, “a fitting tribute,” saith Entertainment Weekly, “to the artist, who died in 1994.” All of which reminds me of Jack Murray and a mysteriously meaningless billboard outside Bowers, a village in Pennsylvania. The billboard depicts an iconic Nancy holding a telephone to her ear. No words accompany this cryptic image. But it is a perfect evocation of Bushmiller’s surreal comic strip. According to Dan Hartzell, “The Road Warrior” in the Allentown Morning Call, motorists along the road are perpetually puzzled by the sign because it doesn’t seem to be advertising anything. Some people speculate that the wordless image is a cute way of seducing prospective advertisers, saying, without saying, “Call to rent this space.” But there’s no phone number. Others, who mistake Nancy for a character named “Mary Jane” who was associated with a brand of candy, think the sign is a secret message to marijuana dealers. Mary Jane, “MJ,” being shorthand for the cannabis commodity. But it is neither of those things. It is, in fact, nothing at all. And that’s the joke. The billboard is a “public curiosity,” said Murray, who owns the culprit company that put up the Nancy sign. About twenty years ago, Murray unintentionally became owner of a small billboard company in Bowers. He doesn’t like billboards, seeing them as “an aesthetic blight,” so, unlike so much of entrepreneurial America, he decided to strike a blow on behalf of the landscape. “I decided to do a kind of ‘tithe’ thing,” he told Hartzell, “and make sure at least one of my signs had no discernible advertising intent—no discernible purpose, for that matter” other than to look good rather than blightish. Subsequently, he ran across an old newspaper with a Nancy stip in it and was reminded that he admired the strip “stylistically.” Said Murray: “I thought Nancy might make a nice billboard, something fun to drive past in a ‘huh?’ kind of way—and a good way to mess with the neighbors at the same time. It became a surprise ‘hit’ with my Mennonite neighbors, and drove everybody else nuts. I tend to pick on the humor-impaired anyway—an admitted character flaw.” Hartzell continues: “Strangely (or maybe not), the old-world Mennonites determined pretty quickly that the painted-wood sign was just a gag while some of Murray’s ‘English’ neighbors ‘got near-apoplectic,’ wondering why anyone would ‘do such a thing,’ wasting perfectly good advertising space,’ Murray said. ‘I was enjoying playing dumb and letting the theories fly.’” Nancy, by the way, is still in print, produced these days by Guy and Brad Gilchrist, who have been at it since 1995. Bushmiller died in 1982, and the strip was initially continued by Al Plastino and Mark Lasky (1983), then unsuccessfully “modernized” by Jerry Scott (1984-1994, before he started writing Baby Blues and Zits). Brainard’s Nancy works were probably first widely circulated in Brian Walker’s 1988 tome, The Best of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, which provided a lingering look at the Nancy strip mechanism. Bushmiller’s strip was a textbook demonstration of how the essential character of a comic strip (in which words make sense only in conjunction with pictures and vice versa) can be perverted. In Bushmiller’s Nancy, the punchline was always in the picture in the last panel, coupled to some accompanying or preceding setup remark by Nancy or Sluggo, her bald boyfriend. The joke always depended upon our comprehending both words and the pictures. So perfectly did Bushmiller’s work illustrate the medium that the American Heritage Dictionary, in a rare display of lexical acumen, used a Nancy strip to illustrate the definition of “comic strip.” Bushmiller was reputed to concoct gags by riffling through the pages of a Sears catalogue, which yielded an unending parade of props suitable for making gags of without any regard for whatever the personalities of his characters were. In fact, they had no personalities. Nancy and Sluggo were as much props for the gags as the furniture and other accouterments Bushmiller culled from the catalogue. The bland off-worldliness of Bushmiller’s strip and mind has spawned a cultural phenomenon, a mysterious but pervasive fandom that bands together under the rubric of “the Bushmiller Society.” The Bushmiller Society, or BS, is presumed to be responsible for Nancy’s face showing up on stickers affixed to walls and the doors of men’s room stalls and the like. But no one knows anyone who admits to being a member of BS. Some years ago, Shannon Wheeler, annoyed by the mystery, attempted to get to the bottom of it all. “I talked to various longtime observers of the comics scene and listened to various theories. Most industry fingers pointed to Denis Kitchen, longtime publisher (Kitchen Sink Press), cartoonist and a rumored prankster. Wheeler asked Kitchen, point-blank, if he was the power in the Bushmiller Society. Kitchen laughed: “Let me put it this way, Shannon. No one knows how to contact Superman, right? But everyone knows that you can reach Superman through his best friend Jimmy Olsen. Think of me as someone who has access to this group. Think of me as the Jimmy Olsen of Nancy fanatics.” Wheeler pursued the issue with admirable tenacity; and Kitchen dodged for hours until he slipped up and, while speaking of the BS’s possible application for 501( c)6 status as a non-profit religious organization, used the word “we.” Trapped, Kitchen fled before he could commit further indiscretions. Another of Nancy’s most famous fans was Samuel Beckett, author of the supremely existential and endlessly impenetrable play “Waiting for Godot.” Beckett initiated a correspondence with Bushmiller that lasted for several months in late 1952 and early 1953. The exchange between the two, published in 1999 in Hermenaut No. 15 with an introduction by A.S. Hamrah, is a majestic example of two people talking past each other, neither understanding quite what the other is about but each assuming he understands perfectly. The existentialist Beckett assumed from what he saw in Nancy that he could write gags for Bushmiller, that his existential comedy would be in perfect sinc with the strip. But Bushmiller simply couldn’t comprehend what Beckett’s gags were; he saw no humor in them. One letter includes the following: “Your gag and strip ideas for Nancy are much appreciated, and I have to say interesting, too. Many readers send me ideas for the strip, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen any quite like yours. ... I don’t know how well they’re going to work. I think the problem you’re having, Sam, is the same problem any literary man might have. You’re not setting up the gags visually and you’re rushing to the snapper. It seems to me you’ve got the zingers right there at the beginning, in panel No. 1, and although I have to admit you got Nancy and Sluggo in some crackerjack predicaments, I don’t see how they got there. For instance, putting Nancy and Sluggo in the garbage cans is a good gag, but in my opinion, you can’t have them in there for all three panels. How did they get there? Same thing when you had them buried in the sand. I like to do beach gags, but I don’t think that having Nancy buried up to her waist in the first two panels and then up to her neck in the third one is adequately explained, and I’ve been at this game for a while now. Also, why would Sluggo be facing in the opposite direction when he’s talking to her?” Boggling. We’ll reproduce the entire exchange and Hamrah’s text in Hindsight one of these days. Stay ’tooned.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com, and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s http://www.strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon. ASSOCIATION

OF AMERICAN EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS Incorporating many quotations lifted directly from the Editor & Publisher reports of David Astor.

Moreover, this year, political differences were less notable because the real question was one of survival: not only is the editoonery profession on the endangered species list, but the AAEC itself has spent itself to the brink of financial collapse. The meeting site, not far from the historic Alamo, may furnish future generations with the rallying cry of yore as we all try to forget that the old Spanish mission provided the backdrop for the last best conclave of the inky-fingered faithful. In the face of such dire forebodings, Presidential Elections are reduced to their proper place among the trivia of American entertainments, the candidates joining such icons of popular culture as Miley Montana, Britney Hilton and Paris Spears. Anna Nicole Jones. Still, the 4-day convention was not without moments of high excitement, or, at least, satirical gesticulation. F’instance—The luncheon speaker on Thursday was David Ignatius, a Washington Post columnist and one-time editor, who travels widely, including numerous trips to Iraq. He was asked if he thought pundits who were wrong about the Iraq Invasion should lose their jobs. Saying, first, that he’d have to be added to a list of such writers, he concluded that columnists who retain readership and try to learn from their mistakes should stay on the job. But, he added, “I think people should be fired if they’re not honest, if they don’t tell the truth.” From the audience came a loud cry: “Then you favor the impeachment of George W. Bush!” The comment came from Clay Bennett, once at the Christian Science Monitor and now at the Chattanooga Times, who, since arriving at the Tennessee newspaper, seems to me much more relaxed and free-wheeling than he was when he was at the Boston-based Monitor, a reflection, perhaps, of the Monitor’s attitude toward staff political cartoonists, who are expected to toe the party line—or, at least, not stub their toes on it by opining views too sharply at variance with those of Christian Science. Or so I would suppose, left to my own imaginings. Ignatius rambled across the political and international spectrum in one of the most measured and even-handed discussions of controversial topics I’ve ever heard. About Iraq, he said: “After completely screwing it up, we have in fact begun to do a better job. I don’t want to paint too rosy a view of what’s still a nightmare,” he added, “but there has been a learning curve.” About the declared intentions of Obama and McCain, he said no matter who is elected, voters will be disappointed. Obama will not be able to extract U.S. troops as fast as he and his supporters think he can, and McCain will not be able to “win” as decisively as he and his supporters think he can. About GeeDubya, Ignatius said he’d be quite a subject for biographers of the future, given his Iraq-related mistakes and his lack of public remorse about those mistakes. “With LBJ,” Ignatius said, “you could hear the anguish in his voice about Vietnam. He was a tormented man. You don’t get that feeling with Bush.” Clay Bennett piped up again, saying Bush’s apparent lack of remorse and his failure to take responsibility “seems frightening and twisted and sick to me.” Ignatius continued in the same vein: “It’s disturbing how the U.S. has become habituated to lying” from politicians in recent years. Thanks to the Bush League, “it’s scary to see how angry people in other countries are with the U.S. That could be our biggest national security problem.” David Astor concluded his E&P report: Speaking more generally of editorial cartoonists, Ignatius said he and other columnists are a little jealous of them. “You guys get to be caustic, irreverent, and crusading. We’re pundits and, if we’re in Washington, we’re Beltway insiders. We use layers and layers of words. We wish we could be as quick and clean.” Another non-cartooning guest speaker was Henry Cisneros, once the four-term Hispanic mayor of San Antonio and, for four years under Bill Clinton, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development before being forced to leave under a cloud (he was accused of lying to the FBI about the amounts of child-support payments he was making to a former mistress—his own money, perforce, but he was obviously a sexual sinner, everybody’s political no-no). Cisneros, long a supporter of the Clintons, had just returned, flying all night, from meetings with Clinton and Obama supporters in Washington, where Cisneros spoke, advocating party unity. “Hillary Clinton expected to be the nominee and wanted to be the nominee worse than I imagined,” he said. “She’s giving up a dream here, and you could see it in her face. But she’s handling it like an adult.” Her campaign’s mistake, Cisneros believes, is that she picked “the wrong theme—experience at a time when people wanted change.” He concluded his remarks by noting that if population growth continues in its present ruts, Americans will increase by 130 million in the next ten years—and 63% of that growth will be Hispanic; the next most numerous group, Asian (including Cambodia, India, and Pakistan) at 37%; finally, African-American at 27%. He urged that we invest in education “as the gateway to middle class for these populations,” adding in a ringing phrase that “harvesting the talents of the Hispanic population is an American job!” The closing banquet speaker on Saturday evening was historian Douglas Brinkley, a professor of history at Rice University, whose current book in preparation is about Teddy Roosevelt and whose most recent book is The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. These two volumes are related by environmental themes at their cores—TR having established vast reaches of the nation’s reservations of natural resources, and Katrina’s success deriving in part from the evaporation of TR’s second wildlife preserve in the coastal wetlands that, until being depleted by the extraction industry, protected New Orleans by absorbing and thereby diminishing the force of incoming storms. Brinkley’s presentation was a patchwork of these concerns underscored by the question he left us with: What are we about as a nation? He hoped that the election of Barack Obama would re-establish America’s distinctive role in the world. About the Bush League’s role in the destruction of New Orleans, he said, “Inaction is the policy.” The Republicans are interested in the welfare of American business, little else. The investment of big business in the Mississippi valley is characterized by there being 22 Fortune 500 companies in Minneapolis/St. Paul, but only one in New Orleans. The Bush League feels no pressure to rescue New Orleans. Judging from the inactions weighed against the actions, the Republican plan for New Orleans is that the French Quarter be a sort of “Disneyland” tourist attraction; otherwise, the city can continue to serve as one of the minor ports of the nation. Its cultural roots will become a museum-like curiosity embodied in the French Quarter. But about the devastated Ninth Ward where all the African-American poor lived, cultivating a distinctive subculture, the Bush League has no interest whatsoever. That part of New Orleans is the city’s cultural base, and, Brinkley pointed out, the Republicans have no interest in culture. Steve Kelley, editoonist at New Orleans’ Times-Picayune, asked Brinkley why only one major U.S. company is headquartered in the city, and Brinkley explained that the city, historically corrupt with a reputation for crime, seems to most U.S. businesses to be hostile. The single 500 company there is in the ports and docks business.

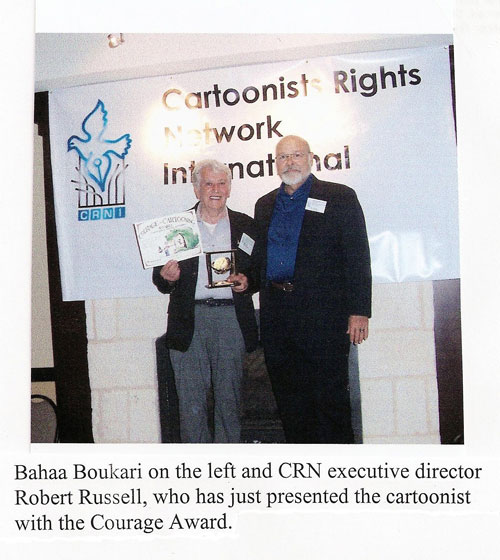

Courageous Cartooning Meeting,

again, in conjunction with AAEC, the Cartoonists Rights Network,

which works with loosely aligned international watchdog organizations

that frequently join together to exert pressure on oppressive regimes

when they threaten cartoonists, sponsored a fund-raising dinner on

Thursday evening and presented its Courage in Editorial Cartooning

Award to Bahaa Boukari, a cartoonist in Palestine, who was arrested

last winter and convicted of insulting the Hamas Parliament. The evening also included hilarious stand-up comedy by AAEC’s own Joel Pett, who editoons at the Lexington Herald-Leader, and Chris Bliss, a comedian and Bill of Rights advocate, whose current project is to get a national monument built to the Bill of Rights (visit www.mybillofrights.org). Bliss is also, he confesses, the world’s most famous juggler—“an assertion impossible to refute,” he claims, adding, “who else can you name?” For a display of his spectacular juggling, visit www.chrisbliss.com; go to “The Big Finale” in the Video Press Kit. I’ve seen Bliss live twice and often return to his website and “The Big Finale” to replenish my often flagging spirits in these days of blinding sun and freezing ice. The

next day, Mike Lester, who cartoons for the Rome (Georgia) News Tribune, perpetrated on an increasingly

bored audience one of his typical SNL pranks: he concluded his

presentation at a panel by mocking Bliss, juggling as he sang the

same song Bliss juggled in tune with. But Lester used only one apple.

And he sings badly. Lester, whose editorial cartoons are usually

powerful as well as pointed, is a perpetual joker, which endears him

to everyone. Sitting

Serious Stuff But the AAEC convention was not all fun and games. At one of the panel presentations, a cross-section of editoonists shared with the audience the hate letters they’d received from readers who disagreed with their cartoons; at another session, a somewhat different cross-section discussed the pitfalls of doing cartoons about the recently deceased—or, as they are known, “obit cartoons.” Ted Rall, who is syndicated with Universal Press, provoked outrage amid the dust of the Twin Towers with his “Terror Widows” cartoon ridiculing the 9/11 widows who were turning their personal tragedies into money-making projects. And he also poked at firefighters to whom the vast public was being directed to send charitable donations: Rall depicted their firehouses awash in donated money. A band of firefighters came to Rall’s apartment building. “I was on the sixth floor, and I looked out the window and saw a big red truck,” Rall said, quoted by Dave Astor, “—there were forty guys in front of the building with axes telling the building superintendent that they were going to kick my ass.” At first, Rall said he didn’t know what to do: “Calling 911 wouldn’t have helped—they would have told me ‘don’t worry, firefighters are on the scene,’” he joked. He finally phoned a friend who had the idea of rushing to the building to take photos of the firefighters; they soon dispersed. At the Sacramento Bee, Rex Babin made fun of firefighters who had attended a porn-star costume ball while on duty. The firefighters orchestrated a massive e-mail campaign against the cartoonist, and one correspondent said Babin might not get service if his house was burning. Clay Bennett said he’d received protest letters smeared with excrement. Recently, he received a communique from an irate reader who alleged that columnist Ann Coulter “has more patriotic blood in one of her used tampons” than Bennett does in his whole body. But Mike Lester had the perfect response. When readers wonder, loudly, why he doesn’t draw “positive cartoons,” his stock reply is: “Because those are greeting cards.” At the obit cartoon session, Mike Thompson of the Detroit Free Press offered a series of “don’ts” that cartoonists should avoid: don’t draw Pearly Gates scenes “unless there’s a twist,” don’t draw a tear coming out of something (like some did with the NBC peacock at Tim Russert’s death), don’t place just-deceased celebrities in heaven just because they’re celebrities, and don’t do a celebrity obit cartoon unless the person merits one (which leaves out Anna Nicole Smith, he said). But obit cartoons are very popular with readers. Joel Pett, whose paper is in Lexington, Kentucky, said he was wildly praised by readers when he drew an image of Barbaro as a horse in the sky after the Kentucky Derby thoroughbred broke two legs and was killed. Assessing the local excitement over his cartoon, Pett deadpanned: “You can’t get enough beating of a dead horse in Kentucky.” The cartoonists displayed some cartoons that avoided cliches, and they offered possibilities for future obit cartoons—among them, the Denver Post’s Mike Keefe’s sketch of Darth Cheney, telling the spectral Death, “F— you.” At other sessions, the issues of the day received attention. During “Wounded Warriors,” Iraq casualties—one without legs, the other with half his face burned off—testified to the superb treatment they experienced at San Antonio’s Center for the Intrepid, often the first stop for many of Iraq’s wounded. Immigration and environmental concerns were aired during “Border Fences.” And in another session, former judges for the Pulitzer and the Herblock awards talked about their criteria for cartooning excellence. Ironically, none of the judges were cartoonists, a strange situation, considering that opinionated imagery must seem an alien tongue to newspaper people whose forte is words. The Herblock may be better equipped in this regard: one of the judges every year is the previous year’s winner, a cartoonist. The non-cartoonists of the panel seemed hung up by almost irrelevant considerations: “What about color?” one wanted to know. Does a cartoonist who works in color have an advantage over one who does not? Perhaps—in cartoons done after the student massacre in Virginia last year, for instance; but black can depict blood as well as red can, albeit perhaps not as gruesomely. Still, “color” in and of itself does not put a political cartoon in a different category from cartoons done in black and white. The criterion ought to be the imagery of visual metaphor, and when that prevails, “color” is an ingredient but not a separate genre. One judge wondered if some political cartoons had migrated into “illustration” rather than cartooning. What? If the illustration expresses an opinion in visual metaphor, how is that different than an editorial cartoon? Sorry: I don’t buy these distinctions, which seem to me largely the preoccupations of wordsmiths who don’t understand the function of cartooning. Multi-panel cartoons—aka, comic strip cartoons—make their points in yet another way, by accumulating “evidence,” so to speak, leading to a politically pungent punchline. All the judges expect to see more animation in future competitions, and Clay Bennett, who doesn’t do animated cartoons, rose in the audience to argue for a separate category for animated political cartoons—a position I agree with. As I’ve said before, in the best animated cartoons, “motion” itself makes the point, and “motion” thereby makes animated political cartoons a different breed than the traditional static visual metaphors. As Bennett said, “An animated cartoon uses a whole different toolbox.” And they deserve, therefore, to be considered differently than traditional political cartoons. Pondering the question of additional categories leads into avenues of labyrinthian complexity. The Pultizer Prize categories are more numerous now than they were at the beginning: as journalism advanced technologically, new categories were added to acknowledge those advances. Excellence in photography and television reportage weren’t recognized at first; they are now. So while the traditions of the Pultizer allow for change, change can open a Pandora’s box of problems. One of the panelists, Pulitzer board member Richard Oppel, said, “Our key concern is excellence in journalism, not technology.” But journalism now includes tv and the Internet as well as newspapers and magazines. And what about those “citizen journalists,” the legions of bloggers on the Web? Shouldn’t they be able to compete for a Pultizer? If the preoccupation of the Pulitzers is “journalism,” then bloggers must be welcomed. But if Pulitzers are confined to print journalism, then Internet bloggers are left out; ditto animated political cartooning. Nothing has been settled yet, nor, in our rapidly changing technological environment, is anything likely to be soon enough. We’ll continue to contend.

AAEC’s Fate This year’s AAEC confabulation registered slightly more than 100 people, counting spouses, children and guest speakers, a notably smaller meeting than in previous years, reflecting, doubtless, a new chariness at newspapers in these threatening financial times: they aren’t willing to pay for their cartooners to go to meetings. Only about four dozen of the 107 registrants were practicing cartoonists. But the AAEC membership roll has grown slightly over the last year, from 392 to 473. The number includes many staff artists who only occasionally do a political cartoon as well as numerous freelancers. W. Cullum Rogers, the AAEC’s secretary/treasurer for life, did a careful count a couple months ago and discovered that there are quite a few more full-time staff editoonists than has been frequently supposed of late. Dire reports for the last year have pegged the number at about 80, but Rogers found 101 full-time staff political cartoonists still working. A number of them, however, are not members of AAEC. Unhappily, last year’s 50th anniversary convention in Washington, D.C. cost more than anyone had planned: logging an income of $86,500, the meeting spent $131,000, leaving the Association with but $20,000 in the bank. How to account for the seeming profligacy? It seems that no one was keeping track of expenses—not the presiding officer and program arranger, Rob Rogers (who actually raised more money to fund events than his predecessors—leading him to think, I suppose, that the convention was on sound fiscal ground), not the management company. Besides, no one had thought to develop a budget for the meeting, so how could anyone know if spending was excessive? No cartoonist could know: as everyone knows, cartoonists are pecuniarily deprived and therefore incapable of discerning profit from loss or any other purely fiscal fact. The circumstance dramatizes the Association’s perennial problem: how to generate revenue enough to fund its programs? For the past several years, a grant from the Herblock Foundation has underwritten the development of the AAEC website, editorialcartoonists.com, but maintaining the operation will cost $8,000 a year, money the Association doesn’t have. While the problem is persistent, discussion of possible solutions remains hesitant and entirely theoretical: neither the management company nor the AAEC leadership has ever taken practical steps to address the dilemma: no proposals have ever been put to a vote by the membership. And my guess is that as long as there’s $20,000 in the bank, nothing will happen, again—despite the earnest and well-intentioned declarations of officers during the annual business meeting. In spite of the evaporating number of full-time staff editorial cartoonists, AAEC leadership is optimistic about the future of the profession. Out-going president Nick Anderson of the Houston Chronicle said: “I’m confident editorial cartooning will survive into the future, but the form it takes, I’m not sure about.” Ted Rall, incoming president (who takes office in September), is more optimistic than not, despite his frequently cynical cartoons. “I’m not taking joy in the country’s situation,” he told Amy Dorsett at the San Antonio Express-News. “Retire the debt, bring the troops home, close Guantanamo, restore habeas corpus, stop invading other countries without good reason, and I’ll go back to investment banking.” But his customary cynicism surfaces on some issues. “Try getting an anti-NAFTA cartoon in the newspaper,” he said. “It would be easier to have a cartoon calling for the president’s assassination. It’s not going to happen. Newspapers are owned by corporations that want to see lower wages, and NAFTA helps push down wages.” Underneath it all, however, Rall is hopeful. “To be a political cartoonist,” he said, “deep down in your heart, you have to think it’s possible for people to change.”

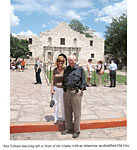

Footnit: As soon as she returned home, one AAEC member reported that when she went into work on Monday morning, her employer at her “day job” in retail advertising, not editooning, which she does “nights,” had eliminated her freelance position. The layoffs, she said, began the previous Thursday, but they didn’t want to ruin her trip with the news. “Thoughtful bastards,” she said. Another Alamo. Another member, this one a long-time staff cartoonist at his paper and a local institution, wasn’t given the same consideration: his employers told him on the very eve of his departure for San Antonio that his full-time staff position had been reduced to freelance status. Now the total number of full-time staff political cartoonist positions is an even 100. (I’ve left off the names here because both people are likely to be in mid-negotiation about their status, and publicity might jeopardize their efforts. Sorry: a Newsweek weasel, I know.) LBJ AND ART WOOD, LOVERS OF CARTOONS Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th President of the U.S. and an inveterate Texan, collected editorial cartoons, usually those in which he, a larger-than-life politician of the venerable arm-twisting school of negotiation, was the chief figure. Beginning early in his career as a congressman, LBJ pursued cartoonists who cartooned him to obtain the original, suitably inscribed by its perpetrator. The earliest artifact in the LBJ archive of more than 4,000 is from 1937. Since AAEC was meeting in the state where the LBJ Presidential Library resides, in Austin, one of the convention’s sessions was devoted to Johnson and his passion for political cartoon originals, which he wanted whether they were positive about him or negative. According to editoonist Art Wood, another collector of cartoons, most of LBJ’s pursuit was ably conducted by Willie Day Taylor, a relative of the President’s wife, who operated out of quarters close to the Oval Office. Wood , a past president of AAEC, is one of the world’s heroic cartoon collectors, and over his lifetime, he amassed a holding of more than 32,000 pieces, representing over 3,000 cartoonists. When he gave the whole magilla to the Library of Congress two years ago (see Opus 195), the LOC collection doubled in size overnight. The convention session on LBJ’s collection included no mention of Wood, but it should have. Wood was as avid a collector of originals as Johnson, and when the two collided—well, that’s the tale, and here it is. Wood began collecting original cartoon art at the age of twelve or thirteen, and he’s probably in his eighties when he gave away his collection, so he’d been collecting a long time. He started by visiting the Washington Star’s editorial cartoonist, Cliff Berryman, who gave him one of his son Jim’s cartoons and one of his own. When Wood found out that syndicates routinely destroyed comic strip art once it had been reproduced and distributed, he persuaded the pertinent factotums to let him paw through the heaps of original art for the best samples for his collection. And when Wood became an editorial cartoonist himself, he approached his colleagues; he even approached me one time, and I sent him one of my unpublished gag cartoons (of which I had several thousand). So now I’m in the Library of Congress. Wood had original work from all the great names in cartooning—Bud Fisher, George McManus, Hal Foster, Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, Alex Raymond, Al Capp, to name a few of the “moderns.” He also had originals by 19th century American ’tooners—Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman, F.R. Opper, Thomas Nast, A.B. Frost, and other giants. One of Wood’s passions once he became an editoonist was getting Presidents to autograph one of his cartoons about them. With thin-skinned Presidents, this proved problematic: they didn’t want to sign a cartoon that was critical of them—John F. Kennedy, for instance. Wood, who shamelessly regales us with his adventures as an obsessive collector in Great Cartoonists and Their Art (Pelican, 1987; 192 8.5x11-inch pages), tells of the time he chased after JFK during the 1960 Presidential Election campaign. After a speech in Pittsburgh where Wood was working at the Pittsburgh Press, Kennedy was mobbed by ravenous teenage girls, and police had to cordon off an escape route for the candidate. Wood, gripped by his compulsion to get his cartoon autographed, stuck to the JFK entourage, elbowing his way through the mob and, finally, shoving the cartoon into Kennedy’s face as he was about to enter his limousine. The cartoon, unfortunately for its maker, did not applaud the candidate, and Kennedy declined to sign it. “When you do a favorable cartoon, Art,” JFK said, “I’ll sign it.” Later, Wood was successful, but getting LBJ to autograph a Wood cartoon required more ingenuity than patience. Wood’s first attempt failed. He’d asked a friend to present his cartoon to LBJ for signature, but Johnson didn’t like the way Wood had caricatured him. “It’s lousy!” he is supposed to have said; “I won’t sign the son-of-a-bitch.” But some time later, Wood stage-managed a publicity event with other editoonists in which the final moment was devoted to Johnson autographing each of the cartoonist’s caricatures of him. Naturally, a Wood caricature was among the array, and naturally Johnson signed it, not wanting to create an incident in front of tv cameras. One reading of this episode is that the entire affair was arranged by Wood for the sole purpose of finagling an autograph out of LBJ. Such is the collector’s passion. REMEMBERING THE ALAMO Most American cities, like most American airports, are so much alike in appearance that you can easily forget which one you’re in. A few, however, are so different in flora, fauna or physique that you know the minute you walk outside your hotel that you’re in that particular city and no other. San Francisco is like that. And New York and New Orleans. And sometimes Seattle, San Diego, and Savannah. And always San Antonio. The rest are all Chicago or Los Angeles. San

Antonio is rendered unique to visitors by the Riverwalk, a loop of

the San Antonio River that was created decades ago as a sort of

backwater canal that is now the tourist mainstem of the city, along

which cluster the major hotels and numerous restaurants, all serving

Mexican dishes, and bistros of every national potable. Before the

Riverwalk, there was only the Alamo. After the Riverwalk, there is

still the Alamo, a monument to the state’s uniqueness: it was a

nation before it became a state, thanks to Sam Houston, Stephen

Austin, and Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, President of Mexico and

sometime general, hero of the 1829 battle of Tampico that drove the

Spaniards from his country forever, whose decision to suppress a

fomenting rebellion in the Texas province resulted in February-March

1836 in a 13-day siege of a former mission compound behind the walls

of which 150 Americans, including Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett, were

commanded into patriotic graves by an erstwhile lawyer named William

B. Travis. The deaths of Travis’ ragtag contingent gave the

Texas rebels a rallying cry that united other ragtags into a stiff

resistance that eventually defeated Santa Anna and established Texas

as an independent country. The incident at the Alamo also gave Texas

and San Antonio its most famous image, the facade of the old mission,

against which millions of visitors have had their photographs taken,

just as I did, accompanied, here, by animating editoonist Ann

Telnaes, who is standing on the curb because,

she said, “I want to be tall for a change.” As far as I’m

concerned, Telnaes always stands tall in her profession, head and

shoulders above many of her colleagues. But that’s another

story. The photographer is J.P. Trostle,

editor of the AAEC Notebook; and

that’s yet another story. As

most visitors to the Alamo eventually discover, the besieged Texans

in 1836 used the building, which was, at the time, a ruin, without a

roof, for little more than a length of wall by which the embracing

fortification of the abandoned mission compound was completed. For several generations of Texans, the story of the Alamo and the history of the state was conveyed in comic strip form in a booklet with the bafflingly inappropriate name Texas History Movies. The bafflement, however, is easily resolved by any attentive student of the history of cartooning. The booklet reprinted a comic strip that had initially been published serially in the Dallas News, beginning in the fall of 1926. Its name was doubtless inspired by other comic strip histories, all posing as frozen-frame movies in the tradition of Ed Wheelan’s Minute Movies, a comic strip that spoofed “the hokum and sentimentality” (as Ron Goulart puts it in his Adventurous Decade) of movies. Wheelan had introduced the concept in April 1918 with Midget Movies, which he did for Hearst’s New York American. When he left the paper at the end of the decade, he continued the comedic cinematography under its new name for most of the twenties, inspiring imitation, among them, Chester Gould’s early effort, Fillum Fables. Meanwhile, back at the Hearst works, E.C. Segar filled Wheelan’s vacant slot with a knock-off of Midget Movies called Thimble Theatre, which debuted December 19, 1919, and ten years later introduced the world to a one-eyed sailor fittingly named Popeye. Texas History Movies was clearly another in a growing list of comic strip “motion pictures.” It was eptly rendered by one Jack Patton, whose talent and bigfoot style easily equal the best of the day. It reminds me not only of Wheelan’s easy caricatural manner but of George Storm’s barely more realistic style in Phil Hardy and, later, Bobby Thatcher. As you can see from the samples here, Patton was happily in the bigfoot tradition, not the illustrative. The quality of the reproduction here, alas, is not high, but my source is pretty scruffy, too.

The strips were accompanied by captions and text, all written by a Dallas News cohort of Patton’s, John Rosenfield, Jr.; I’ve eliminated the text here in the interest of conserving what scarce space there is here in the ethereal world of the Web. After running in the newspaper, the entire production was collected in book form by P.L. Turner Co., which produced a hardback volume in 1928; at the same time, Magnolia Petroleum Co. (which became Socony-Mobile) arranged with Turner to have a paperback booklet printed and distributed to schools throughout the state, a practice that continued into the 1950s. It’s safe to say, as George B. Ward does in the Texas State Historical Association’s 1974 reprint of the volume, that Texas History Movies “has had a significant impact on several decades of Texas schoolchildren. ... The clever, idiosyncratic cartoons captured the imagination of generations of Texans, but a great deal of the cartoons’ charm was found in the frequent use of slang, colloquial expressions, and anachronisms” that Patton sprinkled throughout his work. When Texas patriot Austin, on a mission to Mexico, is captured by a band of Commanches and tied to a tree, he mutters: “Our goose is cooked” in the argot of the Roaring Twenties. The copyright for the production was acquired by the TSHA in 1961, and in 1974 the Houston Chronicle approached the Association about reprinting the booklet as part of a plan to develop an educational program. The original Patton-Rosenfield enterprise, however, was riddled with the racial stereotypes of the 1920s. TSHA assembled an advisory panel with African-American and Hispanic members, and anything offensive in the text or pictures was either revised or removed. Over 100,000 copies were sold to schools at minimal cost to ensure wide distribution. In 1986, TSHA re-issued the volume as a sesquicentennial gesture, and it is to this version that I’ve resorted for the accompanying strips, which focus only on the Alamo; I’ll leave the rest of the book’s history of Texas for you to discover on your own. Incidentally, last year, the TSHA published the New Texas History Movies booklet, an entirely fresh take on Lone Star history, written and drawn (in a much more realistic manner) by Jack Jackson (Jaxon of underground comix fame); it was Jackson’s last work before he died in 2006. CIVILIZATION’S

LAST OUTPOST A woman hiker from Colorado Springs got stuck in the German alps, injured and lost. But she was rescued when she fastened her bra to a supplyline cable that ran by near her. A timber worker saw the bra and energized a rescue team. “It certainly beats sending up a flare,” said one of the rescuers. One wag at his blog opined that “maybe we should consider adding Victoria’s Secret to the Ten Essentials,” the list of ten things all hikers should carry. General Motors will close four North American truck-making plants, responding, in typical capitalistic supply-and-demand fashion, to the declining demand for SUVs. ... In a brochure soliciting subscriptions, Mother Jones reports that “while the rest of us sweat out our taxes, 60% of U.S. companies pay no income tax at all” and “of the top 10 richest people in the U.S., 4 are Wal-Mart heirs—their joint wealth totaling $62,300,000,000" (that’s trillion). The magazine also notes that the lifetime output of CO2 for the average individual is 3.1 tons. “Researchers at SUNY Syracuse added up the average amount of greenhouse gases that will be produced by each child born today.” What a gas. BATSTUFF AND OTHER GUANO Pausing,

slightly, en route to a few words about Christopher Nolan’s

movie“The Dark Knight,” opening July 18, we come upon the Washington Times’ Joseph

Szadkowski, who, writing as Mr. Zad recently at If Miller doesn’t go over the top, he balances precariously on the edge. Issue No. 8 begins with the Joker and a nearly nameless bimbo getting dressed just after sex, but before she can get her blouse buttoned, the Joker chokes her to death, muttering to himself (and to us) all the time about the best way to throttle someone. Very graphic stuff, kimo sabe. And I weary pretty fast of such expostulations as “Dear God” and “Sweet Jesus,” standing in for high emotion. But I think Zad misses the point with Miller’s story. This series is the latest chapter in what we might describe as Miller’s long-term re-casting of the personality of the Caped Crusader. The idea, which Miller hit upon with his 1986 Batman: The Dark Knight, is to examine the psychology of a man whose whole life is shaped by an increasingly obsessive effort to avenge himself upon an underworld that took the lives of his parents. And Miller’s foray into this twisted landscape has been, so far—and continues to be—ingenious: he fits into the traditional Batman mythos a modern psychoanalysis that explains Batman’s perversities but leaves the iconic character in place. In Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder, Miller delves into the relationship between Batman and his young protégé. By the end of No. 9, it’s fairly clear that the boy is redeeming the man: whatever Batman’s initial motives for taking Dick Grayson under his wing following the murder of Grayson’s parents (a psychic echo here), the outcome, so far, is that tutoring and caring for Robin is transforming the brute that Bruce Wayne has become. If I understand Miller’s agenda rightly, Batman will emerge from the experience a more humane and compassionate personality than he was at the beginning. At the beginning—without Robin—Batman is the lusting avenger unredeemed by a single human trait, and the character Zad finds so unsavory is exactly what Miller intends his reader to find. Zad is reacting precisely in the way Miller hoped a reader would. This paves the way for the ultimate redemption of personality which is accomplished by Batman’s fatherly guardianship of Dick Grayson. Although at the first—through many issues of the series—it seems that Batman intends to corrupt the youth, the ironic outcome will be that Robin corrupts, reforms, Batman. Miller’s achievement here is more notable than Lee’s in limning the pin-up characters who flounce through the books. However toothsome Lee’s girlies appear at first blush, their seemingly seductive anatomy does not withstand thoughtful (as opposed to lustful) examination. Lee’s proportions are often wrong, and his perspective is frequently off. I don’t mean that his women have larger busts than nature can tolerate. In a fantasy world, we accept such impossibilities as a routine visual convention. But I can’t be persuaded by all the heavy breathing in the world to accept a distortion that threatens the inner logic of even a fantasy anatomy. A particularly stunning example of this affront occurs in the splash page depiction of the Catwoman in No. 8's introduction of the character: her left shoulder appears to be hooked onto her left breast instead of vice-versa, the usual arrangement of female anatomy. Lee can do faces pretty well, but his rendering of bodies is less than adept—particularly with females. He hasn’t quite mastered the way breasts behave, for instance. Returning to our opening gambit of the Batmovie, Entertainment Weekly’s July 11 issue includes a sizeable chunk of promotional material for the picture, emphasizing Heath Ledger’s triumphant portrayal of the Joker’s “coiled psyche” (admirable phrase, that; who wrote it?). Some observers, according to actor Gary Oldman, who plays Commissioner Jim Gordon as a humble police detective, think playing the Joker drove Ledger into his grave, “but I never saw anything of that,” Oldman finished. Said EW: “As serious a journey as Ledger took into the character, nobody recalls seeing the actor fall down any mental rabbit holes. Contrary to speculation after his death, his work on ‘The Dark Knight’ didn’t appear to ruffle Ledger’s psychological health in the slightest. ‘Heath got the same kick out of acting that I do,’ said Christian Bale, who plays Batman. ‘He enjoyed the sort of crazy immersion of acting. He took it incredibly seriously but simultaneously recognized how ridiculous it all is.’” Michael Caine, playing Alfred the Batcave butler, also immerses himself in a role. “I always make up my own backstories for my characters,” he said. “Nobody cares but me, but I do it anyway. And my backstory for Alfred was that he was with the Special Infantry Service—sort of like the Navy SEALs—during World War II. But he got injured. So in order to stay in the service, he took a job in the officers’ mess as a barman. And that’s where Bruce Wayne’s father found him. That’s why the accent I use for Alfred is that of an army sergeant. You see, you’re not dealing with an ordinary butler here.” But Ledger is likely to be the posthumous hero of the piece, drawing people into the movie who aren’t Batman fans but are Ledger fans and want to “pay the actor their last respects (or who just want to gawk at his ghost). ... The opening weekend numbers are going to be huge. Some observers already predict that the movie could surpass ‘Spider-Man’ to become the highest grossing comic-book-based movie of all time. In an irony the Joker would appreciate, Heath Ledger’s last film is about to be the biggest hit of his life.” PITHY PROCLAMATIONS “Experience isn’t interesting till it begins to repeat itself’ in fact, till it does that, it hardly is experience.”— Irish author Elizabeth Bowen “Normally, your ballroom dancing reminds me a bit of Britney Spears getting out of a care: not very elegant. You sometimes see odd things you’d rather not.” —Len Goodman to a contestant on “Dancing with the Stars,” quoted in Entertainment Weekly. And I love this oft-quoted gem: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion but not to his own facts.” —Daniel Patrick Moynihan “No matter how cynical you get, it is impossible to keep up.” —Lily Tomlin “No pleasure is worth giving up for the sake of two more years in a geriatric home.” —Novelist Kingsley Amis

ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Michael

Turner,

whose glossy stylized drawings made him a comic book superstar from

his first appearance in Image titles in the early 1990s, died in

Santa Monica, California, on June 27 after a long struggle with

cancer. He was only 37. He is associated with pin-up heroines Fathom

and Witchblade (whose costume suggests that a claw-handed creature is

clutching each of her breasts from behind, an undeniably sexy

proposition). Turner had exploited his popularity with fans by

forming his own studio, Aspen MLT, in 2002, but by then, he was

already in the clutches of the disease that would kill him. He was

diagnosed with cancer in 2000—chondrosarcoma in the Tim Russert of NBC’s “Meet the Press” and George Carlin of “Seven Words You Can’t Say on Televison” died last month, within a few days of each other. The Pursuit of Truth will suffer in consequence, more, perhaps, in Carlin’s absence than in Russert’s. The saddest thing about Russert’s death is not his premature departure but the unrelenting flood of teary-eyed encomiums lauding him as an honest and dedicated journalistic truth-seeker who worked hard to acquire the knowledge that made him dangerous as an inquisitor of politicians. His newsman colleagues seemed to be saying: we valued him so highly because he was unique in the qualities we admire in our profession. Shouldn’t all journalists be honest and rigorous in pursuit of fact and truth? Only where they fail in great numbers does the stature of one who succeeds tower so large as to warrant the attention: Russert so loomed over his petty compatriots that when he left the stage, it seemed stark and barren. But

Russert was a showman as much as a journalist; he fit handily into

the “entertainment” mode of contemporary tv journalism.

As David Remnick observed

in the June 23 issue of The New Yorker,

“Russert was no radical. [I’d say, as an entertainer

welcomed into viewers’ livingrooms—RCH], he wanted the

zing of confrontation but was always careful to withdraw at a certain

point, the better not to cross the line between tough and hostile in

the viewer’s eyes. There were limits to his approach, and blogs

both liberal and conservative sometimes purveyed the notion that he

was nothing more than a cozy role-player in the Beltway drama. That

notion was deeply unfair. His preparation insured that a politician

could not drift long in the mental comfort zone.” A good

example of what Russert was and most of tv’s so-called

journalists are not was perfectly conveyed when NBC’s highly

touted former anchor Tom Brokaw took over “Meet the Press”

for the first time on June 29. Brokaw was interviewing the governors

of Colorado and Wyoming, and he asked Bill Ritter, Colorado’s

guv, whether he would welcome a nuclear plant in his state. Ritter

danced around an answer, never saying yes or no. Russert would have

pursued the matter in a follow-up question: “Yes, governor—but

would you want a nuclear plant in your state?” Brokaw passed on

to other matters. Whether Russert was a hybrid, entertainer-newsman,

or not, we’ll miss his persistence, and the public is less weal

without him.

ANOTHER OF THE WATERSHED WORKS OF JACK COLE Cartooning as an artform both literary and pictorial has benefitted from only a few towering geniuses. Winsor McCay, for instance, who worked in several of the genre of the medium, a master in each. Jack Cole was another. Cole, without question or quibble, was a surpassing virtuoso at the medium. He wrote and drew his own material—pencilled, scripted, and inked all of it, most of the time. He is then, the very emblem of cartooning. And in his most remembered creation, Plastic Man, we find, as Art Spiegelman put it in his book, Jack Cole and Plastic Man (2001), the embodiment of the comic book form: its exuberant energy, its flexibility, its boyishness, and its only partially subliminated sexuality. But the rubbery comic book superhero is not Cole's only claim to the laurels he wears in the history of comics. Plastic Man alone is enough to give Cole the nimbus of genius in cartooning, but Cole didn't stop with comic books. He went on to create masterworks in two other cartooning modes—the single panel magazine cartoon and the newspaper comic strip—moving from one to the next in a steady progress of achievement, each work uniquely different, each a watershed landmark in another realm of cartooning, each a triumph of talent and determination. For Playboy, Cole abandoned altogether the linear manner he had deployed so skillfully in comic books and produced startlingly accomplished full-page full-color watercolor cartoon paintings. Playboy’s founder and publisher, Hugh Hefner, a frustrated cartoonist himself, hoped to establish a distinctive look for the magazine's cartoons, and Cole supplied it: his painterly approach to cartooning set the standard for Playboy cartoonists. This was no small accomplishment. Cole had worked almost exclusively with the linear methods of comic book art—solid, unbroken line drawings; even his first single panel cartoons, produced in the early 1950s for the Humorama line of digest-sized magazines as Cole sought to break out of the doomed comic book genre, were essentially line drawings with washes added. But for his full-page cartoons at Playboy, he gave up lines altogether, painting his pictures with no outlines at all. And he was quickly in complete command of the technique. Cole's work for Playboy would have been enough—by itself—to qualify him for a place in the pantheon of the ink-fingered fraternity. But Cole wasn't finished yet. Like most cartoonists of his generation, he had, all his life, set his heart on doing a syndicated comic strip. That's where the big money was in cartooning, and Cole and all his colleagues of the day knew it. So while doing Playboy cartoons, he invented a comic strip and successfully sold it to the Chicago Sun-Times Syndicate early in 1958; it began May 26. Once again, Cole proved himself an innovator. And once again, he changed his drawing style dramatically. Betsy and Me was drawn in the ultra-modern abstract style made popular earlier in the decade by UPA animated cartoons (Mr. Magoo, Gerald McBoing-boing, etc.). More significantly, the storytelling manner Cole employed was a complete departure from the usual funny paper fashion. The

strip was narrated by Chet Tibbit, the diminutive albeit proud

husband of Betsy and father of an unabashed boy genius, Farley. It

was a family strip, but Cole's storytelling was unique: the comedy

arose from the pictures' contradicting the narrative prose. Cole's

fatuous protagonist and narrator would say one thing in the captions

accompanying the drawings, but the pictures of his actions showed the

opposite, revealing Chet to be a trifle pretentious and wholly

delusional. Betsy and Me was the goal toward which Jack Cole had been striving all his professional life. The strip was his Everest, the pinnacle of his aspiration. And having gained the summit, Cole promptly and inexplicably threw himself off the other side and plunged to his death. At the apogee of his professional aspiration, Cole shot himself in the head with a .22 caliber Marlin rifle on a country road near Cary, Illinois on August 13, 1958. Because the fulfillment of his lifelong desire coincides so exactly with the most profound symptom of a sense of failure, suicide, it is tempting to suppose that the two are inextricably connected—that Betsy and Me must somehow contain the explanation for Cole's taking his own life, that the strip may be the key that will unlock the mystery. And that’s what I try to do, with the considerable aid of Clay Geerdes and Art Spiegelman, in the Introduction of Betsy and Me (90 6x9-inch pages, b/w with two pages in color, $14.95), a new book from Fantagraphics Books (FBI), which, in the Introduction, supplies both a biography of the cartoonist and an appreciation of his work in the three genres he commanded so uniquely. With

this volume, Fantagraphics completes the reprinting ritual, so far,

of the ouevre of Jack Cole. DC Comics has started reprinting Plastic

Man in its archival series. (Why, with the eighth volume, they

stopped, I can’t say—except to urge that they complete

the project.) And FBI has published many of Cole’s girlie

cartoons for Humorama in The Classic Pin-Up

Art of Jack Cole with Alex Chun. Betsy

and Me, then, is the last of Jack Cole as

well as the sad final chapter. Working with fugitive photocopies of

syndicate proof sheets and other less-than-perfect materials, most

supplied by Greg Beda (who

inaugurated the project by asking me, out of the blue, if anyone ever

thought to reprint all of Cole’s legendary comic strip; and I

passed the question on to Fantagraphics) and Hal Higdon (through me), others by the

Cartoon Research Library at Ohio State University, FBI’s team, Greg Sadowski with

scanmaster Paul Baresh, has produced an eminently satisfactory reincarnation of the strip in

as complete a run as possible. It includes all of Cole’s

work—through his last daily, September 6, 1958, and his last

Sunday, September 14—plus most of the effort of Cole’s

successor, Dwight Parks, who attempted, with modest success, to continue the strip but could

not mimic Cole’s eccentric genius. According to Jeff

Lindeblatt’s index, Parks may have done

the strip into December 1958, his last daily dated December 10; his

last Sunday, November 23. This book includes none of Parks’

Sundays but all of the dailies through November 29. As complete a

record, as I said, as is, at present, possible. Now if only we can

persuade Hefner to collect all of Cole’s Playboy cartoons, we’ll have as much of this

cartooning genius as we have of McCay. Footnit: In our Hindsight department, we posted, in November 2003, an analysis of Cole’s work on Plastic Man with some biographical emendations, but the biography in the aforementioned FBI book is more complete. By the way (although not at all incidentally), I have a couple extra copies of Betsy and Me, which I am offering for sale here at $10 each, including p&h and, uniquely to this website, an autograph on the Introduction. Write me at the address below for further instructions if you want to buy a copy. MOTS AND QUOTES “The most entertaining show on the air for the past five months has had it all: power-hungry lawyers, cross-country chases, snipers on airport tarmacs, fire-breathing preachers, and one famous former (White) Housewife looking more desperate by the day. That’s right, we’re talking about the 2008 Democratic primary race, which has been the best thing to happen to tv drama since what’s-her-name shot J.R. ... It’s the best season of ‘The West Wing’ ever.” —Benjamin Svetkey in Entertainment Weekly. “The difference between perseverance and obstinacy is, that one often comes from a strong will and the other from a strong won’t.” —Henry Ward Beecher “Boys will be boys, and so will a lot of middle-aged men.”—Kin Hubbard FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE The Bat Lash 6-issue mini-series, the origin tale of the title character, has finally wound down to a conclusion with Bat’s family slain by the vengeful father of the girl Bat loves, and the girl, Dominique, sequestered in a convent, renouncing the world and her beau, determined to be a nun. We knew their romance was doomed all along: in the Bat Lash series of a few decades ago, he’s unencumbered by wife or girlfriend, and since we know that, we can also surmise that his first love couldn’t have endured. But we know the star-crossed lovers are fated to be separated from the internal evidence in this series. In No. 5, Dominique shoots and kills her father because he was about to shoot and kill Bat. Patricide is not a permissible sin, even in comic books, so Dominique must pay a price—in this case, she gives up all hope of romance or marriage with Bat. And Bat rides off into the sunset, now a wanted man: he killed the sheriff, a thoroughly bad guy who almost raped Dominque and was about to kill one of the town’s prostitutes. It’s a messy, grim tale, scarcely evocative of the jaunty, devil-may-care Bat Lash of the original incarnation. Moreover, the story itself is a hackneyed convulsion, jammed with unlikely coincidence and threadbare cliches—an evil sheriff (of Nottingham?) in the employ of a nasty power-mad land-owner (Dominique’s father), Bat and his family on the wrong side of the tracks (Romeo and Juliet?) but befriended by the local Indian tribe because the Lashes treat Indians humanely, like normal human beings. There’s even a cattle stampede. Writers Sergio Aragones and Peter Brandvold may have chosen cliches as a way of satirizing the Western genre—in fact, that sounds like an Aragones maneuver—but it doesn’t come off as a satire. Brandvold is, we are told, an accomplished writer of Westerns, and the dialogue throughout this series is ample evidence of his intimate familiarity with the argot of the antique West. But he hasn’t the light touch that Denny O’Neil deployed in fleshing out the plots Aragones supplied. O’Neil’s

Bat was forever inveighing against violence—“Everyone

knows us Lashes are a peace-lovin’ lot,” he’d say