|

|||||||||||

|

Opus 209 (August 7, 2007). Our normal evolution at this time of

year is to regale you with a report on the menace of the San Diego Comic-Con.

But not this year. I was there, true enough (albeit for only two days),

flogging the Caniff biography to a fare-thee-well. But as you read this, I’m in

transit between Illinois and Colorado, my computer dismembered in the back seat

of the car, a trek that commenced as soon as I got back from the Coast. I’m

required to keep both hands on the steering wheel at all times, so I’m unable

to type anything about Sandy Eggo. Maybe later, much later. Instead, this time,

we tell the truth about Tony the Tiger, review Tatsumi’s latest graphic novel

(or, to be technically correct, graphic short stories), announce the imminent

arrival of a glorious book on Alex Raymond, and more. Without further adieu,

here’s what’s here in order by Department:

NOUS R US

Satrapi’s Film Nixed in

Bangkok

MoCCA’s Big Success

Funky Winkerbean Character

Doomed

Cartoon Gets Humor Mag

Banned in Spain

True History of Tony

the Tiger

We’re All Brothers

Obits of David Hilberman,

Founder of UPA

& Shirley Slesinger

Lasswell

BOOK MARQUEE

A Glorious Book About Alex

Raymond A-borning

R&R GALLERY

Pictorial Featuring a Few

Stray Cartoonish Scraps

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEW

Tatsumi’s Second Tome

And our customary reminder:

don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print

friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this lengthy installment

for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu—

NOUS R US

All the News That Gives

Us Fits

Marjane Satrapi, a cartoonist of modest attainments, gained fame more

through the audacity of her first graphic novel, Persepolis, than

through her skill as a visualizing artist. The book, you’ll recall (how could you

not?), shows us Satrapi as a little girl, growing up in the early repressive

days of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. The book’s sudden success, based upon

its antagonism towards the mullah regime in Iran, inspired Satrapi to produce a

sequel in which she traces her life as a displaced teenager. It, too, was a big

success. And Satrapi produced two more graphic novels, riding the crest of her Persepolis books. And then she graduated into animated film, becoming, forthwith, the

director of “Persepolis” the movie. The animated “Persepolis” will doubtless

bring Satrapi even more fame. It is, apparently, just as incendiary as the

books upon which it is based. It was entered into the Bangkok International

Film Festival (July 19-29) but was ultimately rejected by the festival

organizers because, as the Iran Farabi Foundation put it, the film “presented

an unrealistic face of the achievements and results of the glorious Islamic

Revolution in some of its parts.” The film first incited the

government-affiliated Foundation’s ire when it was screened at the Cannes Film

Festival in France earlier in the spring. “Iran’s rulers are criticized in

‘Persepolis’ but so are Western democracies for backing the Shah [who was

overthrown in the Islamic Revolution] and supplying his government with

weapons,” saith Reuters. Chattan Kunjara na Ayudhya, director of the Bangkok

festival, was “invited” to the Iranian embassy to discuss the matter, he said,

“and we both came to mutual agreement that it would be beneficial to both countries

if the film was not shown. It was a good film, but there are other

considerations,” he finished.

We

may marvel and shake our heads bemusedly at the folly of letting government

agencies dictate aesthetic decisions, but we aren’t far from a similar circumstance

in our own fair land. The Bush League last year bypassed the customary

Congressional approval mechanism to make Erik Keroack Deputy Assistant

Secretary for Population Affairs, the official in charge of the national family

planning program. A harmless enough action, you might think, but Keroack was

then serving as medical director for A Woman’s Concern, a crisis pregnancy

organization with a policy that states: “Birth control ... is demeaning to

women, degrading of human sexuality, and averse to human health and happiness.”

The organization’s mission is to encourage “abortion vulnerable” pregnant women

to make a different choice “to reflect the love of Christ.” Keroack is also on

the advisory board for the Abstinence Clearinghouse. At an abstinence leadership

conference, he wrote in a PowerPoint slide that “PRE-MARITAL SEX is really

MODERN GERM WARFARE.” At another, he defended abstinence by claiming that sex

causes people to go through oxytocin withdrawal, which, in turn, prevents

people from bonding in relationships. That talk was entitled, with unintended

irony, “If I Only Had a Brain.” And this

is the guy who’s in charge of our country’s family planning program?

And

that’s not all. On May 9, I’m told (by another in the dissident ranks),

GeeDubya signed into law a directive, the National Security and Homeland

Security Presidential Directive (NSPD-51), that grants him almost complete

dictatorial powers in the case of a national emergency—such emergency to be

determined and declared by the President himself, another one of those circular

self-serving circumstances by which The Decider grants himself supreme power

“in time of war,” the war in question—the one on terror—being described, by

GeeDubya the Decider, as, for all practical purposes, endless, which

effectively makes George WMD Bush Dictator for Life. His new directive supersedes the National

Emergency Act, which gives Congress the power to “modify, rescind or render

dormant” such emergency declarations if Congress determines that the President

acted inappropriately. George W. (“Warlord”) Bush has simply set aside that

law, invalidated it, because it interferes with his need for absolute power.

GeeDubya’s

popularity has plummeted, reaching sub-30 levels, which reinforces the view

lately espoused by political comedian Will Durst that he will “go down in

history as the worst President EVER, and that includes William Henry Harrison,

the guy who gave a three-hour inaugural speech in the rain [without a hat],

caught pneumonia and served 30 days prone in a sick bed until becoming the

first President to die in office.” But GeeDubya’s achievements in office are

insidious and widespread and will easily survive the plunge in his popularity

polling results. Judging from the Keroack appointment and countless other

“under the radar” appointments, I feel confident in asserting that the

contagion that George W. (“Whopper”) Bush’s initial popularity fostered has

permitted and enabled his self-righteous morally-based governmental philosophy

to penetrate into every nook and cranny of the federal bureaucracy by

dispatching thereto of bevies of like-minded souls. It will taken a generation

of diligent digging by officials of a more pragmatic persuasion to pry these sanctimonious

scoundrels out of office. In the meantime, the Bush League’s heaven-sent

missionaries will be adhering to the otherwise disenfranchise policies of

GeeDubya and his cronies in religious righteousness in their enforcement of

federal programs for years and years yet to come before they are all discovered

and defrocked.

Ooops—sorry:

got carried away there. Back on this planet, we learn, from Douglas Wolk at

publishersweekly.com, that this year’s Comic Art Festival in New York,

June 23-24, was bigger than ever. Sponsored by the Museum of Comic and Cartoon

Art (MoCCA), the Festival strained its meeting venue, the Puck Building

in downtown Manhattan. The exhibit was so enthusiastically subscribed that it

overflowed its usual ground-floor habitat, spreading into the building’s upper

floor rooms and forcing the programming to move inconveniently to the Museum’s

offices a few blocks away. But there is little question that MoCCA’s Festival

is up-and-coming—and may have already arrived. Its usual audience is “more of a

fine art crowd than most other conventions,” Wolk said—those who collect

limited-edition prints and mini-comics as objets d’art; but it is

attracting more and more attendees from beyond the indie-interested bunch. Many

of the exhibitors, publishers and cartoonists alike, have a foot in both camps,

mainstream as well as independent. Wizard magazine, the breathlessly

fan-boy periodical of the industry, had a booth this year, and Houghton Mifflin

was previewing its two fall releases, an English-language edition of Frederik

Peeter’s romance-and-HIV memoir, Blue Pills, and this year’s Best

American Comics anthology, edited by Chris Ware. It’d be a shame if the

Festival has to move out of the historic Puck Building, one of the last

monuments to American cartoon art, named, as it is, for one of the nineteenth

century humor magazines that nurtured the art form into life and gave it

longevity. But success will brook no obstacle; a move to another venue is

surely not too far in the future. This year’s Art Festival Award went to Alison

Bechdel, by the way—a virtual exemplar of indie-gone-mainstream, from an

obscure alternate weekly newspaper strip, Dykes to Watch Out For, to a

best-selling graphic novel, Fun Home. Well done, all around.

Kudzu, Doug Marlette’s daily syndicated comic strip,

will cease this month, reported Editor & Publisher. The last daily

release is for August 4; the last Sunday, August 26. Sunday strips are

typically produced 4-5 weeks earlier than the dailies, which are usually

delivered to a syndicate 4 weeks before publication date. ... Bill Hinds produces several comic strips, and in one of them, Cleats, about

juvenile sports and their coaches, one of the characters, Edith, went to summer

camp on July 23, reported E&P; there, she met the title character

from Hinds’ Tank McNamara, which he co-authors with Jeff Millar,

and Buzz from Buzz Beamer, a feature Hinds creates for Sports

Illustrated for Kids magazine.

In

the Wall Street Journal for July 18, newspaper revenues from advertising

sales were down almost 5% compared to last year. “Since the beginning of this

year,” reported Emily Steel, “the rate of decline in advertising revenue has

accelerated.” Classified advertising has lost to the Web, and the abysmal real

estate market chipped away at another traditional source of advertising

dollars. The dismal industry outlook has colored discussions both in the

Murdoch offer to buy the Wall Street Journal and in the Tribune

(Chicago) Company’s effort to get out of the stock market by going private; the

Tribune intends to buy back its stock, backed by real estate mogul Sam Zell.

... Keno Don Rosa, once in charge of the Information Center at the

revered Rocket’s Blast ComiCollector and then the master mind and hand

reviving the Barks ducks, has one of the world’s best comic book collections,

and he’s selling it off. Well, parts of it: 400 CGC-certified comics, the cream

of the DC Comics titles during the 1970s and 1980s. “There are still hundreds

of Don Rosa books waiting to be graded at CGC,” said Matt Nelson, owner of

comicpedigrees.com, where you can see a list and scans of all the titles so far

unleashed into the auction maw. ... Duncan Hewitt at Newsweek International tells

us that China’s leaders once feared animation as a corrupt foreign influence

but now see it as their country’s next export industry.

FUNKY WINKERBEAN

CHARACTER TO DIE

Associated Press: July

20, 2007

Despite e-mails from readers

asking him to save her, Funky Winkerbean creator Tom Batiuk says

the comic strip character Lisa Moore will succumb to breast cancer. Batiuk, 60,

himself a cancer survivor, said the miracle some readers are hoping for won't

happen.

I honestly don't think readers know what they want, he said. They think they know what they want. But what they

really want is for me to give them a surprise every now and then.

The

King Features strip, which is published in about 400 newspapers, will chronicle

Lisa's experience through October. It is written and drawn by Batiuk in his

workshop above his home's garage in the Cleveland suburb of Medina.

Funky

Winkerbean started in 1972 and at

first focused on gags about teenagers at the imaginary Westview High School.

Over the years, Batiuk has used it to explore sensitive topics such as dyslexia

and teen suicide. Lisa was first introduced in the early 1980s as a high school

student who became pregnant without being married. The strip has chronicled her

often determined and whimsical approach to life's challenges. She was first

diagnosed with breast cancer in 1999 and underwent a mastectomy and

chemotherapy. The story line resulted in a book, Lisa's Story. Batiuk

returned to the story line in April 2006 after he had undergone successful

treatment for prostate cancer three years earlier. He said it gave him new

insight into the disease. He said he knew what was going through Lisa's mind,

because all those dark thoughts crossed his. Last year, Batiuk completed the

Lisa saga now running in the papers. He has moved on to a different story arc,

one that shows what happens to the Funky Winkerbean characters a decade

after Lisa's death. He laughed at what he knows is coming in the lives of his

characters.

I have a real leg up on people, because I know how

cool the work is going to be and how much fun it is to see these characters as

parents, he said. I'm having a ball with it.

First,

though, Lisa must die, leaving behind her husband, Les, and a daughter.

To me, there is a miracle in Lisa's story, Batiuk said. It's not that much of a downer. It's a hopeful story,

because it shows how a loving couple treats each other under all

circumstances.”

On the Net: http://www.funkywinkerbean.com/

SPAIN: GRAPHIC CARTOON

CAUSES ROYAL FLUSH

By Victoria Burnett: New

York Times, July 21, 2007, with additional information culled from the

London Times, Associated Press, and news.yahoo.com

A senior Spanish judge has

ordered the police to confiscate copies of a satirical magazine, El Jueves, which hit the newsstands on July 18 with a cover cartoon that depicts Crown

Prince Felipe having sex with his wife, Princess Letizia, a former tv news

anchor. Judge Juan del Olmo wrote in a court order that the cartoon may have

broken laws protecting the royal family and the dignity of the crown. El

Jueves director Albert Monteys Homer called the order a direct attack on freedom of expression. The ruling “shows that we still lack political

maturity,” said Julio Rey, a cartoonist for El Mundo newspaper.

“It’s terribly important for the system to be able to laugh at itself,” he

added.

The

cartoon mocked a measure instituted by Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez

Zapatero to boost Spain's birth rate by offering $3,450 to families for each

new child born or adopted. In the cartoon, Prince Felipe is depicted having sex

with his wife and gleefully exclaiming: Do you realize if you get pregnant, this will be the

closest to real work I've ever done?

Judge

del Olmo also required publishers of El Jueves to give him the name of

the cartoonist, saying the work might amount to libel against the monarchy.

Libeling the crown could carry a two-year prison sentence, a National Court

spokeswoman said. The cartoonist, who goes by the name Guillermo, expressed

his amazement at the episode: “They’re going to take the printing plates? Why

those haven’t existed for years” he said, before joking: “The best thing would be

for them to cut off my right hand.”

The

editor of El Jueves, Alberto Monteys, said he was surprised by the

decision and joked that readers would win the race against the police and buy a copy before they are removed from

newsstands. If the goal of this move

was for people not to see the cartoon, what will happen now is that it will

appear in all television stations and newspapers, he said.

Spanish

law calls for a prison sentence of up to two years as well as fines for those

found guilty of slandering or defaming the king or his descendants, although

penalties are very rarely applied. The Spanish public reveres its royal family,

and publications generally steer clear of its private affairs. According to the London Times, many people believe that Spain’s three-decade taboo

against criticizing the royal family is on the point of collapse with a huge

public appetite for gossip being met increasingly by Internet sites that are

harder to control. Media censorship is rare in Spain, though it was often used

during the 1939-75 dictatorship of General Francisco Franco. The last

publication to be censored was another satirical magazine, El Cocodrilo,

in February 1986 for another reference deemed disrespectful to the head of state.

During its 30 years of publication, El Jueves has often been critical of

Spain's monarchy, and has been asked by the royal household to reflect on its contents, the newspaper El Pais reported on its Web site. This ruling was the third time the magazine, which

does not hide its republican sympathies, was censored by the judiciary, the

newspaper El Mundo said on its Web site. Elsewhere on the Web, those

enterprising souls who managed to obtain copies of the magazine before it

disappeared from the newsstands were offering it in auction where copies of it

went for up to $138 apiece.

Fascinating Footnote. Much of the news retailed in this segment is culled

from articles eventually indexed at http://www.rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html,

the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John

Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature,

cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to

numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. Three other

sites laden with cartooning news and lore are Mark Evanier’s www.povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s www.DailyCartoonist.com,

and Tom Spurgeon’s www.comicsreporter.com. And

then there’s Mike Rhode’s ComicsDC blog, http://www.comicsdc.blogspot.com

A FEW WORDS OF WISDOM

FROM WILL ROGERS

Don’t

squat with your spurs on.

If

you get to thinkin’ you’re a person of some influence, try orderin’ somebody

else’s dog around.

After

eating an entire bull, a mountain lion felt so good he started roaring. He kept

it up until a hunter came along and shot him. Moral: When you’re full of bull,

keep your mouth shut.

Never

kick a cow chip on a hot day.

Never

miss a good chance to shut up.

TONY REDUX

Tony the Tiger, the Kellogg

mascot for Sugar Flakes, turned 50 in 2003, and in Opus 117, June 15, I made

mention of this anniversary, saying, also, that Tony had been created by Jack

Tolzien, now 86, who was then disputing claims by others to the

distinction. Last fall, Tolzien, browsing the ’Net like any good octogenarian,

came across my paragraph and thanked me for the support. “Unfortunately,” he

wrote, “I made a more profitable job change as soon as Tony took off. This

opened the door for the guys who took over my work after I left Burnett to get

more credit than they deserved. I made them look good by giving them something

to work with. Sad, but Burnett hardly knows I exist even though I did the grind

there for seven years (1946-1953).” Then he sent me a copy of the cartoon he

sent to Burnett when he learned that people there had never heard of him.

Jack Tolzien’s Story

I worked for Leo Burnett

Adv., Chicago, as an art director during 1946-1953. As an art director I was

assigned in 1950 to work on the newly acquired Kellogg account. In 1952, a new

product named Sugar Frosted Flakes was to be introduced. My job was to create

an image or creative direction for this new product. Because of the

sugar-coating this said to me that it had to be a kid’s cereal. I checked out

the cereal shelves in our local grocery to see what I need to do to make the

new Kellogg product stand out against the competition.

I

had such a steady flow of work with the mix of other Kellogg products, I found

I could do my best creative thinking on that daily train ride to work. I lived

in a Chicago suburb. After a number of weeks of scribbling, finally an idea

started to jell. I wanted something that could stand the test of time. Kids

like animals, and I saw nothing to compete with this on the shelves. A tiger

would be colorful, especially if I put a big red bandana on him to humanize

him. Tony would be the perfect name, and it was only natural that he would be

saying ”They’re GR-R-REAT” He

was to be a friendly tiger, no teeth showing, and the art done in a postery

style. I showed these rough ideas to my creative supervisor, Jack Baxter. He

gave me an okay to go ahead. I designed a package, an introductory ad, and an

introductory trade piece. These were then presented to the agency’s creative

review board. They approved. This creative concept was then presented to the

client. They liked it and wanted us to go ahead as fast as possible. The time

frame was tight because this was going on around the first of December, and

Kellogg wanted to introduce the product in a test market in Miami right after

the first of the year.

I

had to get out art for the package first. Flats had to be printed to start

packaging for that Miami test market distribution. My first choice to do the

Tony art was Alice and Martin Provenson. I liked the work I saw of theirs in

the Golden Books. To save time because of my work load, I asked a Chicago art

rep named Jack Kapes to get in touch with the Provensons ASAP to start the work.

He even flew out East to get them started, but they could not do the work in

the time allowed because of other work they had lined up. So we used a Chicago

artist, Phoebe Moore, to do the first Tony. She did a perfect job, so we were

off and running.

The

test market introduction went well, so Kellogg decided to do a national product

roll-out in the fall after Labor Day. The Miami introductory ad was designed

for 4-color newspaper. After some creative afterthoughts, I was asked to add

Tony Jr. to the package design. An introductory ad in October 1953 ran in Life. I want to mention that at this time, there was no money budgeted for tv.

Reading

what history I see about Tony credits, I see the Provensons are mentioned, and

also the guy that did the voice-over later on when tv money was budgeted. But

nothing was said about Jack Tolzien who created Tony. This

voice-over guy even claimed he came up with Tony saying “They’re G-R-REAT” C’mon—Tony was saying that in print ads before any

tv production was done. Without my idea, there would be none of this. I left

Burnett in October 1953 to go with another agency. Others that took over my

work have claimed they created Tony. I made their jobs easier by giving them a

good creative concept to work with.

Doing

my early thinking about using animals I also had “Katy the Kangaroo” wearing a

floppy straw hat with a flower in it. See these rough sketches. This

is long and detailed, and I hope you will see I know what I’m talking about—and

thank you for giving me the credit I deserve. Burnett hardly knows I exist, nor

do they like to give out credit. Tony the Tiger is one of the top advertising

icons in this country. Creating him is a proud personal achievement for me.

Both Kellogg and Burnett gained much from my creativity. It’s been a financial

and business bonanza for both of them. All I want is recognition, based on

truth. Thanks for listening.

RCH again: Thanks for telling the story, Jack. And now we all know.

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND

WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH

Sometimes happy,

sometimes blue,

But I’m so glad I ran

into you---

We’re all brothers, and

we’re only passin’ through.

Old Folk Ballad Lustily

Sung By Walt Conley in His Trademark Husky Rasp of a Voice at the Last Resort in Denver, Lo These Many Years

Ago

DAVID HILBERMAN, DEAD AT

95

Co-creator of UPA Studio

& Leader of Disney Strike

By Charles Solomon, Special

to the Los Angeles Times: July 21, 2007

David Hilberman, whose union

activities at Walt Disney Studios and brief membership in the Communist Party

led to his blacklisting and shadowed a long career that included founding the

innovative United Productions of America studio, has died. Hilberman, 95, died

of natural causes July 5 at Stanford University Medical Center, according to

his family.

David Hilberman was inadvertently, almost accidentally,

a pivotal figure in animation history, said industry historian John Canemaker. Because of his politics in organizing the Disney

strike and his artistic vision in co-founding UPA, he became a major factor in

changing forever how the Hollywood cartoon was made and what it looked like.

A

native of Cleveland, Hilberman came to Los Angeles to work at Disney in July

1936 as one of 40 young artists who had been recruited in a national talent

search. Within 18 months, he advanced from trainee to layout artist. He worked

on numerous animated shorts, including Farmyard Symphony (1938) and Ugly Duckling (1939), as well as the features Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Bambi (1942).

Hilberman

said he had no complaints about Disney until the 1940s, when the studio was

dealing with rising production costs and the wartime loss of the European

market that had provided nearly 45% of its income. He became one of the leaders

of the union movement, which climaxed in the bitterly fought animators' strike

of 1941.

After

the strike, Hilberman joined with fellow ex-Disney artists Zachary Schwartz and

Stephen Bosustow to found Industrial Film and Poster Service, a small studio

that produced films, film strips and graphic materials for defense contractors

and the Army and Navy. The fledgling studio received its first big break in

1944, when the United Auto Workers commissioned Hell-Bent for Election, an animated cartoon short supporting President

Roosevelt's campaign for a fourth term. In late 1945, the rapidly expanding

studio was reorganized as United Productions of America, UPA.

Bill

Melendez, the Emmy-winning director

of the animated Peanuts television specials, worked with Hilberman at United

Productions. He recalled in a 1986 interview, Dave was a stolid bear of a guy. He was like a

bricklayer, and that was the way he operated the studio: He build it solid, and

every film he did was solidly made. Dave was a great filmmaker and a great

teacher — so calm. We were all young and kind of scatterbrained and didn't know

what to do: Dave was always oil on troubled waters. I can still hear him,

'Let's think about it, let's discuss it: This is what it is, this is what it

isn't.'

Hilberman

sold his share in United Productions to Bosustow shortly after the

reorganization because he had been invited to the Soviet Union to help

establish animation studios there. Those plans ended with the postwar political

changes in the Soviet Union, however, so Hilberman instead moved to New York

and partnered with Schwartz and William Pomerance to form Tempo Productions,

which quickly became one of the top commercial studios in the country.

In

1947, film producer Walt Disney testified before the House Un-American

Activities Committee about the 1941 strike, which he believed was

communist-led. Disney said one artist was the real brains of this, and I believe he is a

communist. His name is David Hilberman¼. I looked into his record and I found that, No. 1,

he has no religion and, No. 2, that he had spent considerable time at the

Moscow Art Theatre studying art direction, or something.

Disney's

testimony and a comment by gossip columnist Walter Winchell that Hilberman was

a communist forced the closure of Tempo Productions. Although Hilberman had

spent six months working at the Leningrad State People's Theater and attending

the Leningrad Academy of Fine Art in 1932, he frequently denied ever having

been a communist.

But

in 1979 he told Canemaker, Up

to the war, for about three years, I was a communist. Once the war came along,

everybody plunged into the war effort, everybody's on the same side¼. The strike itself was not communist-led. I was

floored when some obviously communist-inspired material was put up on the

bulletin board.

After

leaving Tempo, Hilberman did freelance work in England, France and the United

States. He earned a master's degree in theater arts at UCLA in 1965, and taught

film at San Francisco State from 1967 to 1973.

SHIRLEY SLESINGER

LASSWELL DIES

Expander of Pooh's

Empire; Wife of Snuffy Smith Creator

By Dennis S. Hevesi, New

York Times, July 21, 2007

Shirley Slesinger Lasswell,

who inherited the licensing rights to Winnie the Pooh, Eeyore the donkey and

Tigger the tiger, too, then expanded the market for a panoply of children's

products based on these and other fun-loving denizens of A. A. Milne's Hundred

Acre Wood, died Thursday, July 19. She was 84.

The

cause was respiratory failure, said her daughter, Pati Slesinger. Although she

lived in Tampa, Florida. Mrs. Slesinger Lasswell died at her daughter's house,

in Beverly Hills, Calif.

A

singer and dancer, Shirley Basso was performing on the road in California in

1947 when she met Stephen Slesinger, a literary agent and the merchandiser of

fictional characters like Tarzan and Red Ryder. They married a year later. In

1930, Mr. Slesinger had paid $1,000 for the licensing rights to the characters

in Milne's books and poems revolving around the roly-poly teddy bear, sometimes

simply called Pooh. Adapting E. H. Shepard's famed sketches of the Milne

characters, Mr. Slesinger developed and marketed Pooh products until he died in

1953. It was then that his wife took over the business and began to expand it.

She had artists revamp the old drawings to simplify

the lines, Pati Slesinger said. Then she pounded the pavement and peddled her ideas

in all the wholesale districts of New York: the toy district, clothing

manufacturers, the gift and specialty makers.

The

product line grew to include, among many other items, children's clothing,

jewelry, wall hangings, coloring books, storytelling records, cutout books and,

of course, stuffed animals. To promote the products, Mrs. Slesinger Lasswell

(whose second marriage was to the cartoonist Fred Lasswell, best known

for his work on the comic strip Snuffy Smith) persuaded upscale stores

like Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue and Nieman Marcus to allow her to set

up Pooh Corners in their stores, where children's tea parties and book readings

could be held.

In

1961, Mrs. Slesinger Lasswell signed over the commercial and television

licensing rights to the Walt Disney Company in exchange for continuing royalty

payments. The deal would lead to a long-running legal battle [which is, in most

respects, still being waged].

Shirley

Ann Basso was born in Detroit on May 27, 1923, one of two daughters of Michael

and Clara Leasia Basso. Her father, a jewelry importer, died when she was 5.

Her mother worked at a local post office during the Depression but managed to

save enough to pay for singing and dancing lessons for her daughters. Mrs.

Slesinger Lasswell's sister, Patricia, died in 2001, the same year as Mr.

Lasswell.

In

the 1980s, while traveling, Mrs. Slesinger Lasswell began noticing Pooh

products in stores—including T-shirts, toothbrushes and videos—that she said

were not included in her royalties from Disney. By the 1990s, according to the Los

Angeles Times, Disney was earning more than $1 billion a year from its Pooh

products and commercial placements. In a lawsuit filed in 1991, Mrs. Slesinger

Lasswell and her daughter claimed that they were owed hundreds of millions of

dollars. The complicated case remains unresolved.

For

many years, Pati Slesinger said, the license plate on her mother's car read, Pooh.

THE FROTH ESTATE

The Alleged News

Institution

According to the last report

I saw before posting this—which, in The Week of July 13, isn’t so very

recent, admittedly—Rupert Murdoch and the Dow Jones board had agreed on the

structure of an oversight committee that would be responsible for protecting

the “editorial independence” of The Wall Street Journal so that Murdoch

could not do to it what he usually does to a newspaper he buys—corrupt its

journalistic ethics in order to subvert the publication to one of his nefarious

purposes. The agreement calls for the committee to be made up of people with no

ties to either Murdoch’s company or to Dow Jones. The Bancroft family, which

holds a controlling interest in the Dow Jones, still has to approve the deal,

but all the signs are that they will. Once he owns the historic paper, Murdoch

will demonstrate how he can get around the oversight committee.

Meanwhile,

from E&P: in the July 22 New York Times Magazine, Matt

Groening, creator of Fox TV’s “The Simpsons,” says he doesn’t like the idea

of his boss buying the Wall Street Journal. Groening admits that he gets

along well with Rupert Murdoch, owner of Fox TV, but “I think he owns enough.”

READ & RELISH

“I’ve

got two goats on my place in Mississippi. There ain’t no fence big enough or

strong enough to hold them. People are at least as smart as goats, maybe not as

agile.”—Trent Lott, explaining that it will take more than a fence along the

border to deal with the immigration problem

“Every

Memorial Day I think about what these men did and what we owe them. They didn’t

go through hell for a political system that functions on bribery, or for

off-shore tax havens that pass the cost of national defense from the

conglomerates that profit from war to the ordinary people whose children fight

it, or for an economic system that treats working men snd women as disposable

cogs to be tossed aside at a predator’s whim, or for an America where the

‘strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.’ Yes, our

soldiers fought and sacrificed for freedom; but as wiser men than I have said

through the ages, when liberty is separated from justice, neither liberty nor

justice is safe, and those who sacrificed for both are mocked. —Bill Moyers on

“Bill Moyers Journal,” May 25, 2007

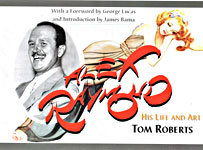

Book Marquee

RAYMOND AND ROBERTS

For as long as I’ve known

him—at least ten years, maybe fifteen or more—Tom Roberts has been

working on a book about Alex Raymond. Tom is a perfectionist as well as

an illustrator—lately, he’s been making illustrations for Moonstone’s Doc

Savage: the Lost Radio Scripts of Lester Dent as well as doing some of the

covers for his own line of pulp story reprints, Black Dog Books, available

through Amazon’s BookSurge imprint—and he wants the Raymond book to look

perfect. Or, if not perfect, at least it should look the way Tom wants it to

look, exactly. He shopped the book around to various publishers, but, for one

reason or another, none of them would serve his purpose. Mostly, they wanted to

tell him how to do the book; and Tom already knew how to do the book, and it

wasn’t quite the way the publishers wanted him to do it. With Adventure House,

however, he finally came upon a publisher willing to let him design the book

his way. And so he has. Tom set the type and laid out the pages; he’d already

written the book and, over the years, refined his selection of illustrations.

And the publisher contributed color on nearly every page. I’ve seen color proof

pages, and the final product is going to be gorgeous, just the sort of setting

Alex Raymond deserves.

The

final result, Tom’s perfect book about Raymond, will be out late this fall,

probably in November—just in time for Christmas, if you’re thinking of

something you can recommend to your spouse as a gift for yourself. In 12x9-inch

format, the volume provides an ample showcase for Raymond art, and Tom has

found troves of rare and sometimes never-before-published pictures. Here’s the cover, for instance. For

the biographical text, Tom interviewed members of the Raymond family and

surviving friends and assistants. The result, which we’ll look at in more

detail here the closer we get to its publication date, is the only complete

biography of the famed cartoonist. Not only does Tom cover Raymond’s early

career assisting on Tim Tyler’s Luck and Blondie as well as his

own oeuvre, Flash, Jungle Jim, Secret Agent X-9, and Rip Kirby,

but he examines Raymond’s lesser known achievements as a documentarian in the

Marines during World War II and as an illustrator of fiction and advertising in

the 1930s and 1940s. And as a devotee of the feminine form. As a kid, Raymond

drew pictures of pretty girls; his earliest published drawing, at the age of

twelve, was of a beautiful woman. And the book contains a

never-before-published series of photographs of Raymond drawing from a nude

model. Like most cartoonists, Raymond, as a routine matter, drew from images in

his head; most of the photographs we see of him drawing from a model are staged

for publicity purposes. But occasionally, to keep his mental images real, he

hired a model and drew from the model. This series represents one of those times.

Tom’s perfect book brims with such rarities as these; don’t miss it if you can.

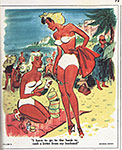

RANCID RAVES GALLERY

Shreds and Patches

from Better Bygone Days

By way of preparing the way

for the forthcoming Hindsight piece on John Held, Jr., here are a couple

works by Held’s chief rival in the retrospective competition for Definer of the

Jazz Age—Russell Patterson. These two pages are from the old humor

magazine Life in 1933 when the periodical was on its last legs. And if

the legs Patterson presents herewith are any indication, the last legs were

undoubtedly the best. By this time, Life was monthly. The first page is

from an August issue; the second, from October.

Then from Circulation, the legendary in-house (syndicate) magazine produced by King Features in those dear dead days, are page-size illustrations in which: Jimmy Swinnerton portrays himself as a cowboy (in order to provide a target for all those Indians he used to draw for a woman’s magazine and for Little Jimmy and various of his other creations); Billy DeBeck’s Barney Google cavorts; Cliff Sterrett arranges for his Polly to put on a fashion show through the ages and then offers examples of some decidedly different “comic art”; and, finally, a color cartoon by Michael Berry, which shows us what he was particularly good at, but since it appeared in Collier’s magazine, it probably disqualified him for Playboy, which Hugh Hefner hoped to stock with cartoonists more-or-less exclusive to his magazine.

Onward, the Spreading

Punditry

The Great Ebb and Flo of

Things

The more we learn about the

machinations of Our Government, the more we wonder about how a democracy works.

Here are some relevant paragraphs from a recent (last winter) column by John

Hightower (an admittedly unreliable truth-seeker-and-spreader of the raving

liberal ilk—my kind of people, that is).

Aon

Corporation is a Chicago [Illinois] -based global conglomerate that counts

Sterling Life Insurance Company among its subsidiaries. Last year, Aon

lobbyists had written a little amendment that would have made a big change in

the Medicare insurance program—a change that (surprise) would have given an advantage to Aon over other

insurers. [But Congress didn’t go along with the scheme. At first.] Indeed,

when the House-Senate conference committee hammered out the final version of

their Medicare bill [to reconcile the House and Senate versions of the bill],

Aon’s change was specifically rejected. Yet, when the voluminous bill was

passed into law, four sentences that neither the House nor Senate negotiators

had approved miraculously appeared down in the dense text. They were the exact

four sentences that Aon wanted, bending the Medicare law in its favor.

From

whence cometh this legislative miracle? From that old corporate favor-doer,

Denny Hastert, [Congressman from Illinois and also, not at all incidentally,]

then the GOP speaker of the House. After the House-Senate negotiators had

rejected the amendment—and just hours before the bill was voted on by the full

House—Hastert appointed himself a majority of one and had the rules committee

surreptitiously tuck Aon’s special-interest provision into the bill. Denny,

ever the legislative prankster, did not bother to mention his banana-republic

coup to the conference committee negotiators so they ended up voting

unwittingly for a bill that contained the very giveaway they thought they had

stopped. ... Will it surprise you to learn that Aon has been a loyal campaign

donor to Hastert and the GOP?

RCH

again: As you can see, Our Government is no longer for the people, by the

people, and of the people. The people—unless they happen to be lobbyists,

corporate interests, or Congressmen—have little to say about the machinations

of Our Government. And as far as Congress is concerned, as I’ve said before, it

appears to exist solely as a place for various elected personages to meet to

decide how to divvy up the spoils—namely, the tax revenue to which we all

contribute—by legislating into being one pork barrel project after another,

each aimed at making things better for some business interest back in their

home district. The decision-making is mostly about trading votes: you vote for

my pork, and I’ll vote for yours. Public weal be damned.

Footnit: Revisiting

the Seat of Government to Make a Good Story Better. Last time I recounted my attempt after the AAEC

convention in Washington to enter the U.S. Capitol building to view the Rotunda

and the Hall of Statues, only to be rebuffed by a dutiful security guard who,

on the look-out for Islamic hostiles, said the only way I could get into the

place was as a member of a tour group. That’s it, then, I thought to myself: citizens can no longer just walk

in whenever they want and see “their”government at work. So it’s effectively no

longer “our” government, the government of the people, by the people, and for

the people. It belongs to someone else, and it works unobserved. In secret. The

terrorists have won. And since they’ve won, the War on Terrorism is over, and

we can bring the troops home.

When

I told this story last time, I forgot to add that last sentence. I hadn’t

thought of it yet. But now I have, and so I do.

A LITTLE DIALOGUE IS A

DANGEROUS THING

Back in the Golden Age of

television, “Hollywood Squares,” a game show with panelists who were usually

comedians, created hilarious havoc from time to time, asking questions that the

panelists could resist answering. Here are a few:

Q.

Do female frogs croak? A. If you hold their little heads under water long

enough.—Paul Lynde

Q.

Which of your five sense tends to diminish as you get older? A. My sense of

decency.—Charley Weaver

Q.

In bowling, what’s a perfect score? A. Ralph, the pin boy.—Rose Marie

Q.

It is considered in bad taste to discuss two subjects at nudist camps. One is

politics; what is the other? A. Tape measures. —Paul Lynde

Q.

According to Ann Landers, what are two things you should never do in bed? A.

Point and laugh.—Paul Lynde

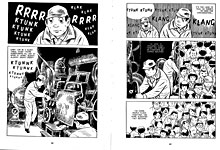

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEW

Tatsumi’s Second Book

If you are as weary as I am

of Japanese comics featuring saucer-eyed, pointy-chinned young girls in short

skirts flashing their underpants, you’ll welcome, as the cleansing gust of a

spring breeze, the latest collection of short stories by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Abandon the Old in Toyko (202 8x6-inch pages in black-and-white; Drawn

& Quarterly hardcover, $19.95), the second of a proposed 3-volume series

edited by graphic novelist Adrian Tomine. Tatsumi, Tomine reminds us in a

concluding exchange of questions and answers with the Japanese master, is the

coiner of the term gekiga, literally “dramatic pictures,” that he used

to describe a variety of manga that aimed at an adult readership. As a youth

who drew comics in high school, Tatsumi admired the work of the “father” of

Japanese comics, Osamu Tezuka, whom he met and sought critiques from.

“Tezuka

was very much a mentor to me,” Tatsumi told Irma Nunez of Japan Times in

September 2006. Seeing Tezuka’s work was “formative,” Tatsumi said: it

demonstrated the narrative power of the comic book format. But when he

contemplated making his own comics, beginning in the late 1960s, Tatsumi didn’t

want to create works like Tezuka’s. “He was making comics for children,”

Tatsumi said. “My colleagues and I were interested in writing comics from our

own perspective. We wanted to write comic books for adults in which we could

express things more graphically. I incorporated a lot more violence. Part of

that was influenced by the newspaper stories I would read. I would have an

emotional reaction of some kind and want to express that in my comics. What I

aimed to do was increase the age of the readership of comics. It wasn’t that I

was trying to create anything literary, but I did want to create an older

audience.”

It was a matter of

necessity, Tatsumi explained: “There was an incommensurable difference between

what I wanted to express and what you could express in children’s comics.”

The Abandon collection, like its predecessor The Push Man and Other

Stories (Opus 191), is a vivid example of Tatsumi’s success. Children can

scarcely be imagined finding entertainment in these bleak vignettes of everyday life among ordinary

people living in teeming cities and experiencing, as a consequence of the crowded

urban milieu, a spiritual isolation that dehumanizes and destroys. But adult

readers doubtless find a searing kind of truth about the nature of the human

condition. These tales, as Nunez put it, “turn on images of human degradation,

quiet despair and outrageous violence carefully arranged to cinematic—even

symphonic—effect. The underlying beat is that of escapist fantasy pounding its

head against hard reality. This seems quintessential of Tatsumi’s brand of

gekiga.”

The

first of the 8 stories in the book, “Occupied,” may be an ironic metaphor for

Tatsumi’s professional evolution. The title refers to a lavatory in which the

protagonist, an artist who draws books for children, spends much time, studying

the pictures, obscene graffiti, on the walls. Outside the “occupied” restroom,

he imagines, are crowds of people; inside, it is quiet. “I was comfortable

there,” he says. The graffiti change from day-to-day: “It was an endless cycle:

the janitors clean the walls, and people kept scrawling new graffiti.” When he

loses his job, he finds a new vocation by contemplating the lavatory walls. He

is offered a position doing manga for Rude magazine, an “adult”

publication. Suddenly inspired, he dashes to the nearest restroom and begins

drawing a nude woman on the wall, the only place he’s seen “rude” drawings of

the sort, presumably, he’ll produce in his new line of endeavor. But he has

neglected to lock the door of the lavatory, and a woman opens it and discovers

him at work. She screams and calls him a pervert. He flees, but he leaves his

drawing implement in the toilet. We may suppose that when Tatsumi first began

making comics for adults in a culture in which comics were usually for

children, he, like the protagonist of this story, was seen as perverted.

In

the volume’s title story, a young man lives with his aged invalid mother, a

demanding nag. Taking care of her needs consumes every hour not spent at his

job, driving a garbage truck. Like most of Tatsumi’s stories, this one brims

with silent images; wordless pages are filled with crowd scenes. Observing a

wrecking ball razing an old building, the garbage truck driver realizes that

modern life requires getting rid of anything old. In order to achieve a

relationship with a new girlfriend, he decides to rid himself of the impediment

to romance, his old invalid mother. He gets an apartment for her and moves her

into it, carrying her all the way through crowded streets. But later, as he and

his girlfriend board a highspeed commuter train, he suddenly regrets abandoning

her and returns to her apartment, where he discovers that she has died. In the

last scenes of the story, he is seen carrying her lifeless body through the

streets, which, on this day, are filled with demonstrators, pedestrians who

“are here today to take back the streets,” to reclaim a more authentic life

than modernity with its highspeed means of transportation permits. A banner

across the street reads: “Pedestrian Paradise.” In the midst of a happy throng,

we see the young man walking with his dead mother on his back, an evocative

image suffused with message. None of Tatsumi’s stories are happy; they all end in frustration and disappointment, sometimes violently. In “The Washer,” a window washer sees a couple copulating through the window he is washing. Later, we realize what he immediately recognizes—that the woman is his daughter. “Beloved Monkey” shows us a man whose sense of alienation is so profound that he is happy only with his pet monkey. He “frees” his pet by turning it loose in the zoo’s monkey pen, and the monkeys therein gang up on his pet and kill it. Later, as the man crosses a street, he faces a mob of people coming toward him from the other side, and he thinks of his dead pet and screams.

“Unpaid” gives us a poignant portrait of an old man,

once president of his company, who must endure daily humiliations as his

company descends into bankruptcy. In a stunning metaphor, he has sex with a

dog. In “The Hole,” a man falls into a pit, where he is kept prisoner by an old

woman who has been disfigured by cosmetic surgery undertaken to please a man.

Another tale, “Forked Road,” provides a metaphor for a reluctant sexual

awakening with a commuter train track that offers the youthful protagonist a

choice he doesn’t want to make: adult sex is repugnant to him. In “Eels,” a

sewer worker marvels that eels can survive in the sewer. “No one tries to catch

them,” his co-worker observes, “—because they can relate to them. This ain’t no

place for eels. But still, they’re tough enough to survive, and they keep

looking for a cleaner place.” When the young man’s wife miscarries, she leaves

him, calling him a loser; and he captures a couple eels and takes them home. He

cooks one and eats it but doesn’t like it. He takes the other one back to the

sewer, where he releases it.

Moments

of comedy are brief and fleeting, illuminating by contrast the prevailing

personal tragedies of the tales. Tatsumi’s protagonists seldom talk; but their

silent suffering speaks volumes about the spiritual blight of urban life in the

years after World War II. “Economic development was considered more important

than the way people actually lived their lives,” Tatsumi says in the book’s

afterword. “I wanted to depict this situation.” Interviewed by Nunez, he said

he identified with the workers in his stories. “What I’m expressing in these

comics is basically what my emotions were at the time. To me, a comic artist is

a laborer. There’s no difference. Especially in Japan, a comic artist has to be

physically very strong because he’s on a tight publishing schedule and there

are so many pages he must produce. It was quite normal for me to stay up three

days straight to meet deadlines, so I completely identified with the laborer.

And I think there’s an equivalent emotion shared by laborers and

cartoonists—that sudden burst of anger, that feeling of ‘Things cannot go on

like this’ or ‘If things go on

like this, I’m going to explode’” Drawing comics is therefore cathartic, Tatsumi

agreed. “In a way, in these comics, I am confessing something that I couldn’t

tell anyone else. But perhaps for readers, it may have been unbearable to have

that thrust upon them.”

Tatsumi’s

drawing style is integral to the dramatic impact of his storytelling. Rendered

in a simple manner akin to Bill Watterson’s technique—think of Calvin’s

parents, not Hobbes—Tatsumi’s graphic economy renders his artwork unobtrusive,

which has the effect of focusing our attention on the plot. But he reclaims the

visual nature of his medium through extensive use of images that, silently,

reinforce the meaning of the plots. Tatsumi’s wordless panels advance the

story, supplying narrative detail, and they underscore the theme with pictorial

metaphors. With pictures carrying so much of the storytelling load, clarity is

vital, and here again, simplicity serves Tatsumi’s purpose: the uncomplicated

drawings are easy to read and understand. On a few occasions, the simplicity of

the art creates momentary confusion: many of the female characters, for instance,

look alike except for hair styles, and when Tatsumi relies heavily on pictures,

we sometimes don’t know, right away, which characters we’re watching. For the most part, however, his economy in

both visual as well as verbal modes adds to the mood of the tale: the

prevailing “silence” creates an aura of unspecific menace, and the characters

in their isolation seem threatened.

Most

of Tatsumi’s protagonists look much alike: they have faces like the hubcaps of

1940s automobiles—round and without distinctive features. Said Tatsumi: “The

character that looks identical throughout my work is, of course, different in

each story, but he essentially represents my view. You could say I projected my

anger about the discrimination and inequality rampant in our society through

him.” The typical protagonist, the cartoonist noted, is therefore not handsome.

But he is persistent, re-appearing again and again through the Tatsumi oeuvre,

as if searching, like the eels, for a better life.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |

|||||||||||